Abstract

Background

Chronic methamphetamine (meth) abuse in humans can lead to various cognitive deficits, including memory loss. We previously showed that chronic meth self-administration impairs memory for objects relative to their location and surrounding objects. Here, we demonstrate that the cognitive enhancer, modafinil, reversed this cognitive impairment independent of glutamate N-methyl d-aspartate (GluN) receptor expression.

Methods

Male, Long-Evans rats underwent a noncontingent (Experiment 1) or contingent (Experiment 2) meth regimen. After one week of abstinence, rats were tested for object-in-place recognition memory. Half the rats received either vehicle or modafinil (100 mg/kg) immediately after object familiarization. Rats (Experiment 2) were sacrificed immediately after the test and brain areas that comprise the key circuitry for object in place performance were manually dissected. Subsequently, glutamate receptor expression was measured from a crude membrane fraction using western blot procedures.

Results

Saline-treated rats spent more time interacting with the objects in changed locations, while meth-treated rats distributed their time equally among all objects. Meth-treated rats that received modafinil showed a reversal in the deficit, whereby they spent more time exploring the objects in the new locations. GluN2B receptor subtype was decreased in the perirhinal cortex, yet remained unaffected in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus of meth rats. This meth-induced down regulation occurred whether or not meth experienced rats received vehicle or modafinil.

Conclusions

These data support the use of modafinil for memory impairment in meth addiction. Further studies are needed to elucidate the neural mechanisms of modafinil reversal of cognitive impairments.

Keywords: glutamate, memory, methamphetamine, perirhinal cortex, self-administration, object recognition

1. INTRODUCTION

Abstinence from prolonged methamphetamine (meth) abuse is associated with persistent cognitive deficits, even after cessation of drug use. In humans, chronic meth abuse can lead to some deficits in executive function, information processing, and memory (Scott et al., 2007). When cognitive impairments do occur, memory deficits are among the most prominent and recurrent problems with human meth addicts (Ersche et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2007). Further, meth addiction is characterized as a chronically relapsing disorder, and memory impairments can exacerbate relapse episodes (Simon et al., 2004). Ideally, pharmacological treatments that target meth addiction will address both the cognitive and motivational factors driving relapse.

Modafinil is a cognitive enhancing drug approved for narcolepsy treatment and chronic excessive sleepiness during waking hours. Modafinil also alleviated meth-induced cognitive impairments during withdrawal (Ling et al., 2006; Minzenberg and Carter, 2008; Vocci and Appel, 2007), improved memory (Ghahremani et al., 2011; Kalechstein et al., 2010), and increased attention (Dean et al., 2011) in meth dependent participants. Of additional importance, modafinil did not result in euphoria, craving, or medical risks when given to meth addicts (Dackis et al., 2003; De La Garza et al., 2009; McGaugh et al., 2009). Abstinence rates generally increased in meth users treated with modafinil. Nevertheless, the full efficacy of modafinil as an anti-relapse medication remains inconclusive due to compliance issues in one study (Anderson et al., 2012) and sample size in others (Heinzerling et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2013; Shearer et al., 2009).

In preclinical animal models of relapse, we have collectively demonstrated that both acute and chronic modafinil decreased meth seeking in rats (Reichel and See, 2010, 2011). Encouraged by this corroboration between clinical and preclinical findings, we also tested whether modafinil would ameliorate meth-induced memory impairments in a rat model of episodic memory. While not all components (i.e., what, where, and/or when) of episodic memory are testable in rats (Ennaceur, 2010), object recognition tasks can assess some elements depending on specific task parameters (Dickerson and Eichenbaum, 2010; Ennaceur, 2010; Warburton and Brown, 2009). These one trial tasks rely on the innate tendency of rodents to explore environmental novelty (Berlyne, 1950), rather than heuristic learning or changes in the motivational state of the subject (Ennaceur and Delacour, 1988). An object-in-place (OIP) task requires subjects to concurrently remember object and place information and incorporates elements of “what” and “where” of episodic memory (Ennaceur, 2010). As such, this task is ideally suited to study meth-induced episodic memory changes in rats, which incidentally are particularly compromised in human meth addicts (Iudicello et al., 2011; Kalechstein et al., 2003; Simon et al., 2004). We recently demonstrated that experimenter administered and extended (6 hr) access to self-administered meth impaired performance on the OIP tasks in both male and female rats (Reichel et al., 2012a, 2012b).

The extended access self-administration model emulates several characteristics of drug addiction, including the escalation of drug intake over time (Ahmed et al., 2000; Kitamura et al., 2006), compulsive drug seeking (Vanderschuren and Everitt, 2004), and increased motivation (Paterson and Markou, 2003). Further, this procedure also impacts other cognitive domains compromised in meth addicts, such as impulsivity (Dalley et al., 2007), attention (Parsegian et al., 2011), and sensory motor gating (Hadamitzky et al., 2011). Therefore, one purpose of this study was to determine whether modafinil would reverse meth-induced cognitive deficits in OIP recognition memory using both experimenter and contingent meth delivery.

The neural circuitry for OIP memory relies on interactions between the perirhinal cortex, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (Barker et al., 2007), but the neurochemical bases for this memory process have not been clearly defined. Glutamatergic neurotransmission may be a key factor, as it has been extensively implicated in a variety of memory processes (Riedel et al., 2003). Glutamate receptors are divided into ionotropic and metabotropic subtypes. Of particular interest are glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (GluN) receptors, as blockade of GluN receptors in the prefrontal and perirhinal cortices before sampling objects impaired object-in-place associative memory following a 1-hour retention interval (Barker and Warburton, 2008). Further, selective antagonism of the GluN receptor subtype 2B blocked perirhinal long-term depression (Massey et al., 2004), which is essential for novelty recognition (Massey and Bashir, 2007).

As an initial step in determining the potential glutamatergic mechanisms underlying meth-induced OIP memory deficits, we used western blotting techniques to quantify the GluN receptor subtypes, GluN1, GluN2A, and GluN2B in the OIP circuitry in rats following withdrawal from extended access to self-administered meth. Modafinil does not directly bind to GluN receptors (Nguyen et al., 2011), but does modify GluN receptor complexes (Sase et al., 2012). Thus, we also determined whether modafinil would affect the expression of GluN receptors in the prefrontal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and hippocampus.

2. METHODS AND PROCEDURES

2.1. Subjects

One hundred male Long-Evans rats (Charles-River) weighing 250–300 g at the time of delivery were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium on a reversed 12:12 light-dark cycle. Rats received ad libitum water throughout the study and 25 g of standard rat chow (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) daily until self-administration stabilized, at which time animals were maintained ad libitum. Procedures were conducted in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Rats” (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, 1996) and approved by the IACUC of the Medical University of South Carolina.

2.2. Behavioral training and testing procedures

2.2.1. Non-contingent meth administration and object-in-place recognition memory

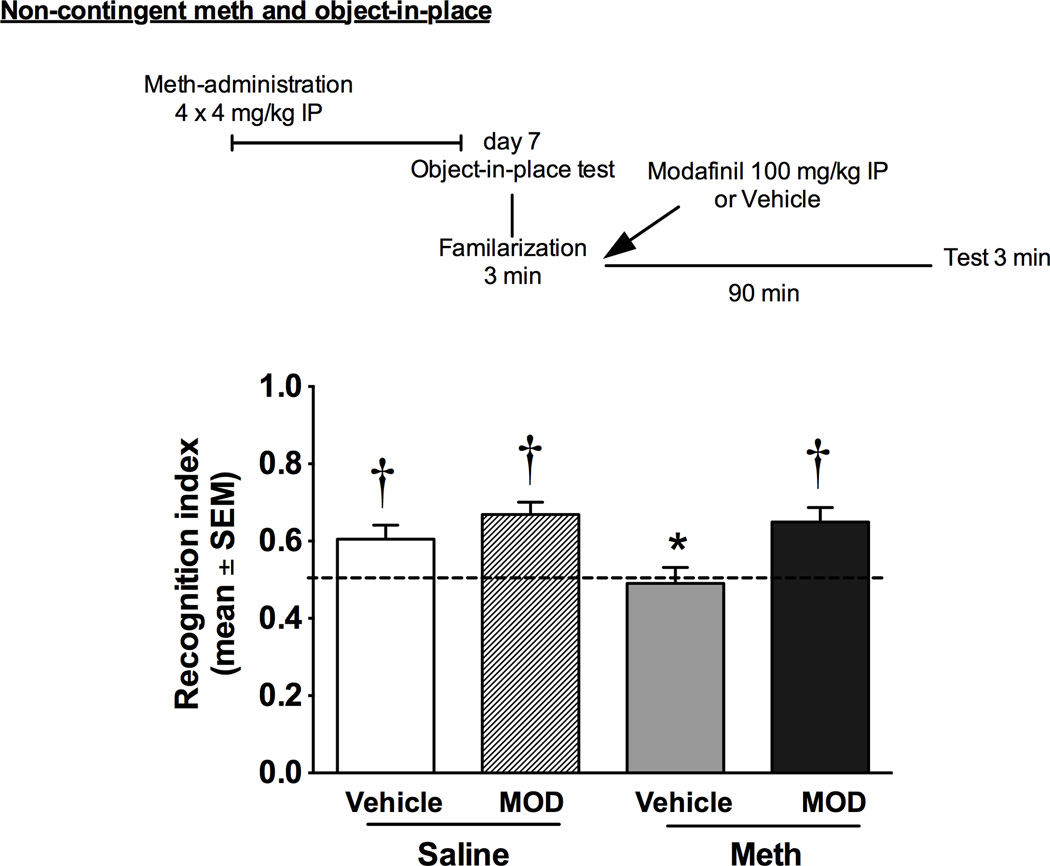

Rats received four 4-mg/kg injections (IP) of non-contingent methamphetamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) or saline at 2 h intervals in their home cage (see Fig 1 for time line). Following this regimen, rats were placed into an abstinence period in which they were handled daily. On days 5 and 6 of abstinence, rats were habituated to the object-in-place behavioral apparatus for 5 min without objects and on day 7, rats were tested for object-in-place. Testing occurred on a round wood open field (98 cm diameter, 3.5 cm thickness, 65 cm above the floor) painted gray. A video camera positioned above the field recorded the sessions. During the familiarization phase (i.e., sampling phase), rats were placed on the apparatus for 5 min with 4 distinct objects positioned 15 cm apart on the round field. A 3 min memory test was conducted 90 min later by placing the rat in the apparatus with the same object, except that the position of two objects was changed. The objects used were chosen based on preliminary research with naïve rats demonstrating that the objects engendered similar exploration and consisted of combinations of a PVC pipe (6.4 × 3.8 cm2), a paint roller (7.5 × 2.5 cm2), a light bulb (8.9 cm), and a plastic bottle (12 cm; Reichel et al., 2012b). The objects that stayed in the same locations vs. the objects that were moved to a novel location were counterbalanced as much as the sample size allowed and matched between meth and saline groups. All objects and the apparatus were wiped down with 70% isopropyl alcohol between uses. To test modafinil’s impact on object-in-place memory, rats received a vehicle or modafinil (100 mg/kg) injection immediately after the familiarization session resulting in four distinct groups: saline/vehicle, saline/modafinil, meth/vehicle, and meth/modafinil. The elimination half-life of modafinil is between 10–13 hr, with behavioral activating effects typically diminishing by 90 min in rats. Modafinil was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada), suspended in 0.25% methylcellulose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and injected IP at a volume of 1 ml/kg.

Fig. 1.

OIP performance assessed at 7 days after noncontingent meth administration or saline (Experiment 1). Data are represented as an index between time spent exploring objects in the changed position/time with both sets of objects. Significant differences from chance exploration (†p<0.05) or control (*p<0.05) are indicated.

2.2.2. Self-administered meth and object-in-place recognition memory

Sixteen standard self-administration chambers (30×20×20 cm, Med Associates) were housed inside sound-attenuating cubicles fitted with a fan for airflow and masking noise. Each chamber contained two retractable levers, two stimulus lights, a speaker for tone delivery, and a house light to provide general illumination. In addition, each chamber was equipped with a balanced metal arm and spring leash attached to a swivel (Instech). Tygon tubing extended through the leash and was connected to a 10 ml syringe mounted on an infusion pump located outside the sound-attenuating cubicle.

For rats that underwent surgery, anesthesia consisted of IP injections of ketamine (66 mg/kg; Vedco Inc, St Joseph, MO, USA), xylazine (1.3 mg/kg; Lloyd Laboratories, Shenandoah, IA, USA), and equithesin (0.5 ml/kg; sodium pentobarbital 4 mg/kg, chloral hydrate 17 mg/kg, and 21.3 mg/kg magnesium sulfate heptahydrate dissolved in 44% propylene glycol, 10 % ethanol solution). Ketorolac (2.0 mg/kg, IP; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was given just prior to surgery as an analgesic. One end of a silastic catheter was inserted 33 mm into the external right jugular and secured with 4.0 silk sutures. The other end ran subcutaneously and exited from a small incision just below the scapula. This end attached to an infusion harness (Instech Solomon, Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) that provided access to an external port for IV drug delivery. An antibiotic solution of cefazolin (10 mg/0.1 ml; Schein Pharmaceuticals, Florham Park, NJ, USA) was given post surgery and during recovery along with 0.1 ml 70 U/ml heparinized saline (Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, NJ, USA).

Following at least 5 days of recovery from surgery, rats were assigned to Meth or yoked-saline control groups. During self-administration, rats received an IV infusion (0.1 ml) of 10 U/ml heparinized saline before each session. After each session, catheters were flushed with cefazolin and 0.1 ml 70 U/ml heparinized saline. Catheter patency was periodically verified with methohexital sodium (10 mg/ml dissolved in 0.9% physiological saline), a short-acting barbiturate that produces a rapid loss of muscle tone when administered intravenously. Daily 1-hr sessions occurred for seven days on a fixed ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement, followed by 6-hr sessions for 14 days. The house light signaled the beginning of a session and remained on throughout the session. During the sessions, a response on the active lever resulted in activation of the pump for a 2-s infusion (20 µg/50 µl bolus infusion) and presentation of a stimulus complex consisting of a 5-s tone (78 dB, 4.5 kHz) and a white stimulus light over the active lever, followed by a 20-s time out. Responses occurring during the time out and on the inactive lever were recorded, but had no scheduled consequences. Yoked-saline controls received a 50 µl bolus infusion of 0.9% sterile saline whenever the matched subject received an infusion of meth. All sessions took place during the dark cycle and were conducted 6 days/week. The OIP memory test used identical methodology as described in the previous section with the test occurring on abstinence day 7 (see Fig 2 for timeline).

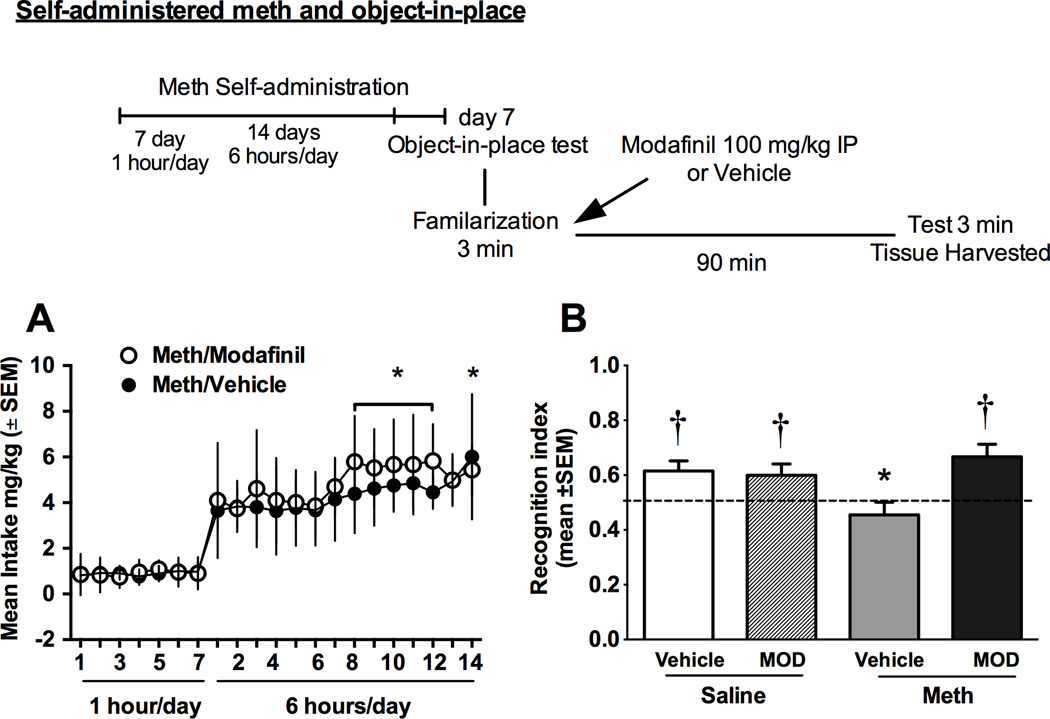

Fig. 2.

Self-administration and OIP performance in rats that received meth or yoked saline infusions (Experiment 2). A) Meth intake during chronic meth self-administration. Open circles represent the group that received modafinil immediately after familiarization in the OIP test and dark circles represent the group that received vehicle. The groups are depicted as such to demonstrate consistent meth intake before cognitive testing. Significant differences from the first day of long access are indicated (*p<0.05). B) Recognition index for meth and saline rats treated with modafinil or vehicle on the OIP test conducted at 7 days after self-administration. Data are represented as an index between time spent exploring objects in the changed position/time with both sets of objects. Significant differences from chance exploration (†p<0.05) or control (*p<0.05) are indicated.

2.3. Tissue extraction and western blot

Rats were rapidly decapitated and brains removed on the 7th day of abstinence from meth self-administration. Using a rat brain slicer (Braintree Scientific, Massachusetts), brains were sectioned into 2 mm thick coronal slices, frozen in isopentane, and stored at −80°C until processed. Regions of interest were dissected from these slices according the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1996). GluN receptors undergo rapid synaptic exchange (Groc and Choquet, 2006). Therefore, in order to determine protein expression of synaptic GluN receptors, subcellular fractions were prepared according to the methods of Fumagalli et al (2008). Tissue was homogenized in a Teflon-glass pestle in ice-cold 0.32 M sucrose containing 1 mM HEPES buffer and protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Complete Mini Protease inhibitor; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN and Halt Phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). To separate the nuclear components into a pellet (P1), the homogenized tissue was then centrifuged at 900g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant (S1) was centrifuged at 12,000g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet (P2) contained the clarified fraction of cytosolic protein corresponding to a crude membrane fraction.

Samples were solubilized in 1% SDS/phosphate-buffered saline containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Equal amounts of protein (15µg) were resolved using SDS-PAGE (4–15%) and transferred to PVDF membrane (BioRad, Hercules, California). The membrane was blocked with 5% weight to volume (w/v) powdered milk/Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 and probed with antibodies for GluN2A (1:500, Millipore), GluN2B (1:2500, BD Biosciences), GluN1 (1:10000, BD Biosciences) or calnexin (1:20000, Assay Designs) overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (1:1000, Millipore) or anti-goat (1:20000, Santa Cruz) secondary antibody at room temperature, followed by washing with Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 (3 × 10 min). Enhance chemiluminescence plus (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, New Jersey) was used to detect protein signal. Equal loading and transfer proteins were confirmed by normalizing our results to calnexin results (i.e., each GluN signal was normalized to the calnexin signal in the same lane). Integrated density of the bands was measured with Image J software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland).

2.4. Behavioral observations and statistical analyses

Time spent with each object was the primary dependent measure during OIP testing. Time with the two objects that remained in the same locations was combined, as was the time spent with the two objects in the new locations; these were denoted as “same” and “changed”, respectively, and referred to as such throughout the rest of the manuscript. Behavior was recorded, stored, and scored with Noldus tracking software (EthoVision XT 6.0, Leesburg, VA), and provided a measure of approach to objects and activity during the sessions. Object exploration was defined as sniffing or touching the object with the nose but not sitting, leaning, or standing on the object. Data (time with the objects) were converted to a recognition index, the primary dependent measure, with the following formula: changed object exploration/changed object + same object exploration. To demonstrate that memory for objects in place occurred for each group, the recognition index was first compared to a hypothetical mean of 0.5. A recognition index of 0.5 indicates equal time spent exploring both objects, greater than 0.5 indicates more exploration of the changed objects, and less than 0.5 indicates more exploration of the same objects. Between groups analyses were conducted with analysis of variance (ANOVA). Meth intake (mg/kg) was the primary dependent measure during meth self-administration and was analyzed with repeated measures over the 14 days of long access. Significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests and the data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Noncontingent meth-induced deficits in OIP recognition memory

Fig. 1 shows recognition indices for rats given noncontingent administration of meth (4 × 4 mg/kg, IP) or saline and then tested with either modafinil (100 mg/kg, IP) or vehicle. Prior to initial testing, exploration values for all groups were equivalent on the familiarization sessions (saline/vehicle, 0.51±0.03; saline/modafinil, 0.48±0.05; meth/vehicle, 0.51±0.05; meth/modafinil, 0.55±0.04). Further, these values did not differ from chance exploration of the objects. On the OIP test (Fig. 1), only meth/vehicle rats spent the same amount of time at each object set, relative to chance exploration. All other groups spent more time interacting with objects in the changed locations relative to chance (saline/vehicle, t(15)=2.9, p<0.05; saline/modafinil, t(11)=5.4, p<0.05; meth/vehicle, t(10)<1, ns; meth/modafinil, t(10)=4.0, p<0.05). Multiple comparisons showed that meth/vehicle rats had lower exploration ratios relative to saline/modafinil and meth/modafinil rats [F(3,46)=4.12, p<0.05 and Tukey’s multiple comparisons, p<0.05].

3.2. Meth self-administration-induced deficits in OIP recognition memory

Fig. 2a shows drug intake (mg/kg) during the self-administration period for meth rats tested with either modafinil or saline. There were no differences between groups in meth intake and both groups escalated meth intake over time. Over the 14 days of long-access, intake on the first extended access session (i.e., day 8) was significantly lower than intake on days 15–19 and 21 [F(13,273)=7.80, p<0.05, and Tukey’s multiple comparisons, p<0.05].

One week after discontinuation of meth access, rats were tested for memory for object-in-place. Fig. 2b shows the recognition indices for meth rats and the yoked-saline controls and then tested with either modafinil (100 mg/kg IP) or vehicle. Prior to testing, initial exploration values for all groups were equivalent on the familiarization sessions (saline/vehicle, 0.51±0.03; saline/modafinil, 0.54±0.04; meth/vehicle, 0.47±0.05; meth/modafinil, 0.53±0.03). Further, these values did not differ from chance exploration of the objects. On the OIP test (Fig. 2b), only meth/vehicle rats spent the same amount of time at each object set relative to chance exploration. All other groups spent more time interacting with objects in the changed locations relative to chance (saline/vehicle, t(13)=3.2, p<0.05; saline/modafinil, t(12)=2.4, p<0.05; meth/vehicle, t(10)<1, ns; meth/modafinil, t(11)=3.7, p<0.05). When directly compared, the meth/vehicle rats had lower exploration ratios relative to saline/vehicle and meth/modafinil rats [F(3,46)=4.62, p<0.05 and Tukey’s multiple comparisons p<0.05]. There were no differences in the number of approaches to the objects.

3.3. Meth self-administration-induced deficits in GluN receptor expression

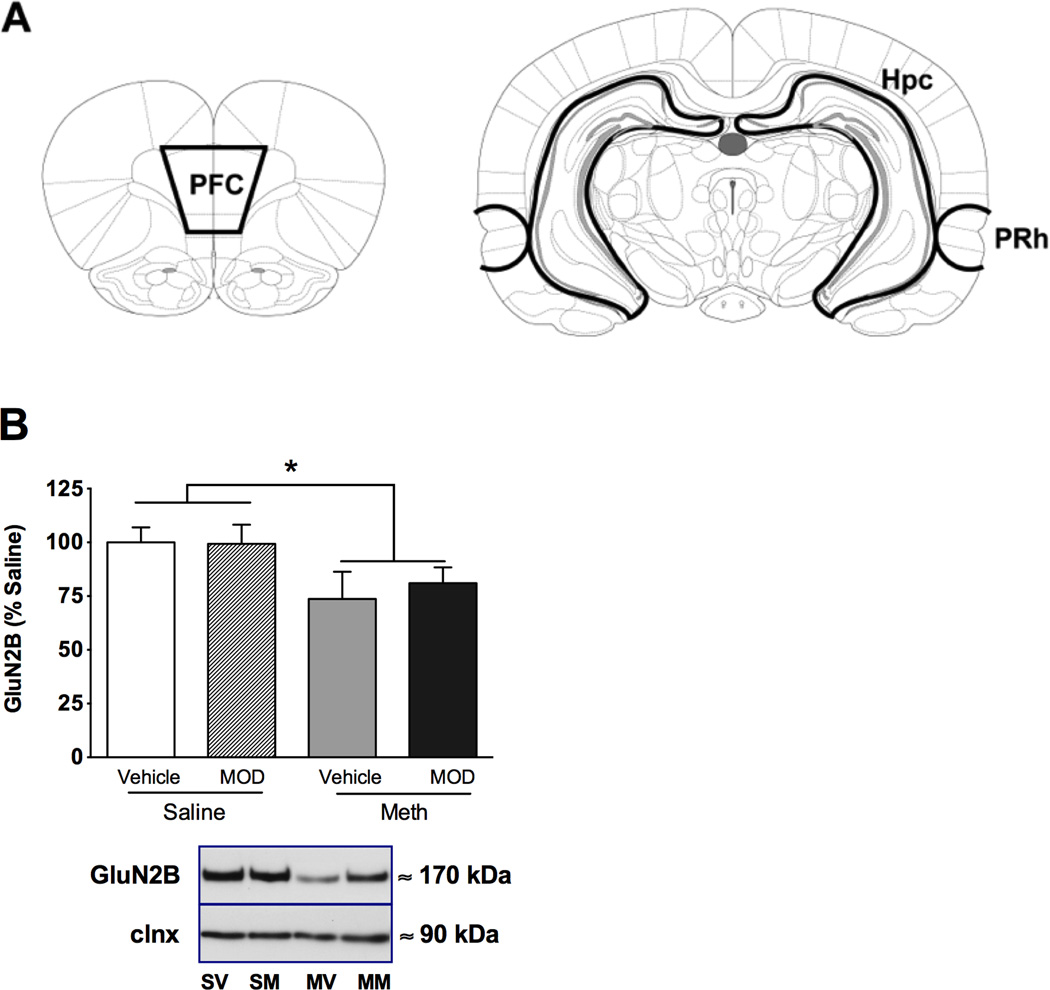

Rats were rapidly decapitated and tissues of interest (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and perirhinal cortex) were dissected on ice from 2 mm thick coronal slices obtained using an adult rat brain slicer (Braintree Scientific, MA, USA). The location of the slices and shape of the tissue samples dissected were chosen on the basis of a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). Prefrontal cortex was hand-dissected from the slice ~2.5 – 4.5 mm anterior to bregma and included the whole prelimbic cortex and part of the infralimbic and cingulate cortices (Figure 3A). The hippocampus was hand-dissected from the slice ~3.5 – 5.5 mm posterior to bregma and included the dentate gyrus and CA1-3 hippocampal regions (Figure 3B). The perirhinal cortex was punched from the same slice using a 2 mm tissue puncher (Sklar Instruments, West Chester, PA, USA; Figure 3B).

Fig. 3.

Figure 3A is a schematic drawing depicting the dissected areas according to Paxinos and Watson (2007). PFC - prefrontal cortex, Hpc - hippocampus, PRh - perirhinal cortex. B) GluNR2B expression in the perirhinal cortex of rats with a history of chronic meth or yoked saline controls treated with modafinil or vehicle. Tissue was extracted immediately after OIP testing. Representative immunoblots depict immunoreactivity in the crude membrane fraction (P2). Immunoreactivity was normalized to calnexin (clnx) and expressed as a percentage of saline control. Significant difference from yoked saline controls is indicated (*p<0.05).

Immunoblotting data, represented by integrated density of individual bands, were normalized to calnexin immunoreactivity within the same sample. Within regions of the OIP circuitry, meth significantly decreased GluN2B receptor expression in the perirhinal cortex [Fig. 3C, main effect of group, F(1,25)=6.37, p<0.05]. However, modafinil pretreatment at the dose that reversed meth-induced memory impairment did not affect GluN2B receptor levels. In addition, no differences were seen between groups in the hippocampus or prefrontal cortex (Table 1). Further, no differences were detected in GluN1 or GluN2A receptor expression for any of the three brain regions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Glutamate NMDA receptor expression (% of saline/vehicle group) following Modafinil (100 mg/kg) or vehicle after 7 days of abstinence from meth SA.

| Group | Saline/vehicle | Saline/Modafinil | Meth/vehicle | Meth/Modafinil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus | ||||

| GluN1 | 100.0 ± 9.7 | 84.4 ± 10.9 | 111.8 ± 4.8 | 113.8 ± 12.5 |

| GluN2a | 100.0 ± 19.9 | 99.27 ± 28.3 | 135.6 ± 25.1 | 118.3 ± 25.8 |

| GluN2b | 100.0 ± 8.1 | 98.2 ± 7.8 | 90.5 ± 3.9 | 105.4 ± 8.7 |

| Perirhinal cortex | ||||

| GluN1 | 100.0 ± 16.6 | 105.9 ± 12.7 | 84.7 ± 19.2 | 77.9 ± 11.9 |

| GluN2a | 100.0 ± 13.9 | 105.7 ± 12.1 | 77.4 ± 6.5 | 104.9 ± 9.1 |

| Prefrontal cortex | ||||

| GluN1 | 100.0 ± 5.9 | 88.7 ± 5.7 | 95.4 ± 4.0 | 91.4 ± 5.0 |

| GluN2a | 100.0 ± 13.8 | 100.9 ± 28.5 | 110.4 ± 23.3 | 95.2 ± 22.6 |

| GluN2b | 100.0 ± 6.3 | 84.9 ± 6.6 | 101.5 ± 6.5 | 101.1 ± 8.2 |

4. DISCUSSION

A single day, experimenter delivered meth regimen and a chronic escalating meth self-administration procedure impaired memory for objects in a particular place (Reichel et al., 2012b and current report). Here, we further demonstrated that modafinil could restore memory function during abstinence from either meth regimen. Restoration of memory function may be a crucial component for treatment of meth addiction, as human meth addicts often report prominent and recurrent memory problems (Ersche et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2007), which may exacerbate relapse episodes (Simon et al., 2004). Further, modafinil is among the first cognitive enhancing drug to alleviate both cognitive impairments and relapse to drug seeking in animal models. To date, modafinil has been shown to reduce relapse to meth seeking under multiple experimental conditions. For example, acute modafinil attenuated meth-primed reinstatement in both male and female rats (Holtz et al., 2011; Reichel and See, 2010). Chronic modafinil treatment during extinction attenuated relapse to a meth-paired context, decreased conditioned cue-induced and meth primed reinstatement, and resulted in enduring reductions in meth seeking even after discontinuation of treatment (Reichel and See, 2011).

Although modafinil enhanced memory function during abstinence from meth, OIP performance did not improve in saline control rats treated with modafinil. This finding could be largely due to a ceiling effect inherent to the OIP task, although it is interesting to note a similar pattern exists in clinical studies. For example, modafinil improved attention set shifting in schizophrenics, without affecting healthy controls (Turner et al., 2004, 2003). In adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, modafinil improved sustained attention, which was unaffected in healthy subjects (Turner et al., 2004). Of interest, the prefrontal cortex mediates attentional tasks (e.g., set shifting and sustained attention) in both humans (Demakis, 2003) and rats (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Parsegian et al., 2011). In regards to OIP memory, modafinil may rectify impaired pre-frontal cortical ability to integrate object and location information in meth-experienced rats (Barker and Warburton, 2008; Barker et al., 2007), yet is without effect in control animals that have uncompromised prefrontal cortex function.

In the first experiment, we used non-contingent meth administration, whereby rats received a series of meth injections in a “binge” (i.e., four 4 mg/kg meth IP at two hr intervals) based on evidence that this regimen reliably disrupts recognition memory (Belcher et al., 2005, 2008, 2006; Bisagno et al., 2002; O'Dell et al., 2011) and results in pronounced neurotoxic consequences (Cappon et al., 2000; Hotchkiss and Gibb, 1980; Wagner et al., 1980). We have previously demonstrated that deficits in OIP memory are independent of the markers of striatal neurotoxicity associated with this meth regimen (Reichel et al., 2012b). In fact, lesion studies have shown that the ability to recognize multiple items and their association to particular locations relies on intact circuitry of areas outside of the striatum, specifically the prefrontal cortex, perirhinal cortex, and hippocampus (Barker and Warburton, 2011; Warburton and Brown, 2009). Disconnection of this circuitry or ablation of any one of these structures is sufficient to impair OIP performance (Warburton and Brown, 2009). Specifically, judgment of a prior occurrence relies on the perirhinal cortex, whereas judgment of multiple items and their contextual associations involve interactions between the hippocampus, perirhinal, and prefrontal cortices (Warburton and Brown, 2009).

The OIP circuitry has been anatomically mapped; however, full elucidation of the neurotransmitters and their cognate receptors that underlie OIP function has not been well explored. We used the escalation meth self-administration model, rather than non-contingent administration, in order to quantify GluN receptor expression in the OIP circuitry based on the ability of the model to best mimic human meth consumption, use patterns, and relapse related events. In addition, extended access meth self-administration reliably disrupts novel object and OIP recognition memory (Reichel et al., 2012a, 2012b, 2011; Rogers et al., 2008). Similar self-administration procedures lead to pronounced neuroadaptive changes within the OIP circuitry, including decreased neurogenesis and reduced hippocampal granule neurons (Mandyam et al., 2008), decreased hippocampal gliosis and altered neuronal firing states (Mandyam et al., 2007), and dysregulated glutamate in the perirhinal (Reichel et al., 2011) and prefrontal (Schwendt, 2012) cortices.

Within the OIP circuitry, cortical glutamatergic neurotransmission may be an important functional mediator. Indeed, in both the perirhinal and prefrontal cortices, non-specific blockade of fast ionotropic glutamate receptors (i.e., 2-amino-3-(3-hydoxy-5-methyl-isoxazol-4-yl)propanoic acid, AMPA) with 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione before sampling objects impaired OIP memory at short (5 min), but not long (60 min) retention intervals. In contrast, non-specific blockade of GluN glutamate receptors with (2R)-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP5) in the perirhinal cortex compromised OIP memory following a 24 hr delay (Barker et al., 2006). Importantly, encoding of OIP memory was blocked by AP5 in the perirhinal and prefrontal cortices and retrieval of these memories required simultaneous GluN receptor activation in both cortical areas (Barker and Warburton, 2008). We quantified GluN receptors in these cortical areas and the hippocampus, and found a reduction of GluN2B receptors only in the perirhinal cortex, which may be a sufficient neuroadaptation to render the circuitry incapable of OIP recognition memory.

Modafinil interacts directly or indirectly with multiple neurotransmitter systems including dopamine, serotonin, histamine, and orexin (Ferraro et al., 2013; Ishizuka et al., 2012; Zolkowska et al., 2009). However, modafinil’s exact mechanisms have not been fully established. Historically, several reports demonstrated that modafinil increased extracellular glutamate in the dorsal striatum, thalamus, hypothalamus, and hippocampus in vivo (Ferraro et al., 1997, 1998). More recently, modafinil increased extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens of cocaine experienced rats (Mahler et al., 2012). Modafinil does not bind to GluN receptors (Nguyen et al.), but does modify NMDA receptor complexes in the hippocampus of mice as indicated by an increase in GLuN1 complexes (Sase et al., 2012). We found no meth or modafinil induced differences in receptor expression in the hippocampus following the OIP place task. Importantly, we isolated the membrane fraction to access GluN receptors following treatment because an acute modafinil injection may not be expected to impact total protein levels found in whole tissue. It is possible that a single injection of modafinil is insufficient to change membrane bound GluN receptor expression, whereas repeated treatment has been shown to have more enduring consequences. For example, mice given 4 ip injections of 80 mg/kg modafinil on consecutive days had decreased GluN1 receptor complexes in the hippocampus. In contrast, rats in our study only received a single 100-mg/kg ip modafinil injection and brains were dissected 90 min later.

Despite the lack of effect in the hippocampus, GluN2B was reduced in the perirhinal cortex, regardless of modafinil treatment. Previously, we reported impaired novel object recognition memory accompanied by reduced metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) expression in the perirhinal cortex following the same meth access protocols as used in the current study (Reichel et al., 2011). Thus, evidence shows that this meth regimen impaired two types of recognition memory that depend upon perirhinal cortex function and resulted in reductions in perirhinal cortex GluN2B and mGluR5 receptor expression. In the perirhinal cortex, long-term depression (LTD) relies on interactions between glutamate receptor subtypes (Cho et al., 2000). In particular, Cho and colleagues (2000) demonstrated that group II metabotropic glutamate receptors facilitate increased group I mGluR receptor mediated increases in intracellular calcium. This increased calcium combined with activation of GluN receptors was necessary for the induction of LTP at resting membrane potential. However, depolarization increased GluN receptor function and removed the necessity for groups I and II mGluR to interact. Under these conditions, LTD in the perirhinal cortex relied on activation of both GluN2B and mGluR5 receptors. As the meth self-administration regimen used in the current study has been shown to down regulate both glutamate receptor subtypes, it is possible that LTD is also impaired in meth-exposed animals, as perirhinal cortex LTD is essential for novelty recognition (Massey and Bashir, 2007).

In humans (Watson and Lee, 2013) and rodents (Wan et al., 1999; Warburton and Brown, 2009), the perirhinal cortex is critical for object recognition memory. The neurocircuitry underlying OIP recognition memory has been mapped, but the neurochemical mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated. Additionally, pharmacotherapies that enhance or rescue OIP memory have not been identified. Here we report that 1) meth impairs OIP memory, 2) modafinil can rescue this deficit, and 3) extended access to self-administered meth decreased GluN2B receptor expression in the perirhinal cortex. This brain area seems particularly sensitive to meth exposure as demonstrated by marked memory deficits in object recognition tasks and dysregulation of glutamate receptors [current report and Reichel et al., 2011]. These tasks can test some components of episodic memory in rodents, which is an element of memory prone to disruption in human meth addicts. Pharmacological treatments for meth addiction have begun to focus on addressing cognitive dysfunction during abstinence or relapse prevention. Previously, we demonstrated modafinil has potential as an anti relapse medication in rodents (Reichel and See, 2010, 2011). Now we extend modafinil’s utility to ameliorating cognitive dysfunction resulting from meth exposure.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants DA022658, DA033049, and F32DA02934, and NIH grant C06 RR015455. MGG and LAR were supported by the Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURP) at MUSC. The authors thank Stacey Sigmon, Weilun Sun, Marek Schwendt, Rebecca Mendel, and Shannon Ghee for technical assistance.

Funding sources: The National Institutes of Health (NIH) provided funding for this study. The NIH had no involvement in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Further the funding source did not have a role in writing the research report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: Author CMR designed the experiments, assisted in conducting the behavioral and neurochemical experiments, and writing the manuscript. Author MGG conducted the neurochemical experiments, assisted in data analysis, and contributed to writing the first draft of the manuscript. Author LAR conducted the behavioral experiments and contributed to writing the first manuscript draft. Author RES assisted in experimental design, writing and editing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed SH, Walker JR, Koob GF. Persistent increase in the motivation to take heroin in rats with a history of drug escalation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:413–421. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AL, Li S-H, Biswas K, McSherry F, Holmes T, Iturriaga E, Kahn R, Chiang N, Beresford T, Campbell J, Haning W, Mawhinney J, McCann M, Rawson R, Stock C, Weis D, Yu E, Elkashef AM. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker G, Warburton E. NMDA Receptor plasticity in the perirhinal and prefrontal cortices Is crucial for the acquisition of long-term object-in-place associative memory. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2837–2844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4447-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GRI, Bird F, Alexander V, Warburton EC. Recognition memory for objects, place, and temporal order: a disconnection analysis of the role of the medial prefrontal cortex and perirhinal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:2948–2957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GRI, Warburton EC. When is the hippocampus involved in recognition memory? J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10721–10731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6413-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GRI, Warburton EC, Koder T, Dolman NP, More JCA, Aggleton JP, Bashir ZI, Auberson YP, Jane DE, Brown MW. The different effects on recognition memory of perirhinal kainate and NMDA glutamate receptor antagonism: implications for underlying plasticity mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3561–3566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3154-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher A, O'dell S, Marshall J. Impaired object recognition memory following methamphetamine, but not p-chloroamphetamine- or d-amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:2026–2034. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher AM, Feinstein EM, O'Dell SJ, Marshall JF. Methamphetamine influences on recognition memory: comparison of escalating and single-day dosing regimens. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1453–1463. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher AM, O'Dell SJ, Marshall JF. A sensitizing regimen of methamphetamine causes impairments in a novelty preference task of object recognition. Behav. Brain Res. 2006;170:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlyne DE. Novelty and curiosity as determinants of exploratory behaviour. Br. J. Psychol. 1950;41:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4320–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisagno V, Ferguson D, Luine VN. Short toxic methamphetamine schedule impairs object recognition task in male rats. Brain Res. 2002;940:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02599-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappon GD, Pu C, Vorhees CV. Time-course of methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in rat caudate-putamen after single-dose treatment. Brain Res. 2000;863:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K, Kemp N, Noel J, Aggleton JP, Brown MW, Bashir ZI. A new form of long-term depression in the perirhinal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:150–156. doi: 10.1038/72093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Lynch KG, Yu E, Samaha FF, Kampman KM, Cornish JW, Rowan A, Poole S, White L, O'Brien CP. Modafinil and cocaine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled drug interaction study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Lääne K, Theobald DE, Peña Y, Bruce CC, Huszar AC, Wojcieszek M, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Enduring deficits in sustained visual attention during withdrawal of intravenous methylenedioxymethamphetamine self-administration in rats: results from a comparative study with d-amphetamine and methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1195–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza R, Zorick T, London E, Newton T. Evaluation of modafinil effects on cardiovascular, subjective, and reinforcing effects of methamphetamine in methamphetamine-dependent volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;106:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AC, Sevak RJ, Monterosso JR, Hellemann G, Sugar CA, London ED. Acute modafinil effects on attention and inhibitory control in methamphetamine-dependent humans. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:943–953. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demakis GJ. A meta-analytic review of the sensitivity of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test to frontal and lateralized frontal brain damage. Neuropsychology. 2003;17:255–264. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Eichenbaum H. The episodic memory system: neurocircuitry and disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:86–104. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A. One-trial object recognition in rats and mice: methodological and theoretical issues. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;215:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Delacour J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res. 1988;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Clark L, London M, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Profile of executive and memory function associated with amphetamine and opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1036–1047. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Antonelli T, O'Connor WT, Tanganelli S, Rambert F, Fuxe K. The antinarcoleptic drug modafinil increases glutamate release in thalamic areas and hippocampus. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2883–2887. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Antonelli T, O'Connor WT, Tanganelli S, Rambert FA, Fuxe K. The effects of modafinil on striatal, pallidal and nigral GABA and glutamate release in the conscious rat: evidence for a preferential inhibition of striato-pallidal GABA transmission. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;253:135–138. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro L, Antonelli T, Beggiato S, Tomasini MC, Fuxe K, Tanganelli S. The vigilance promoting drug modafinil modulates serotonin transmission in the rat prefrontal cortex and dorsal raphe nucleus: possible relevance for its postulated antidepressant activity. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2013;13:478–492. doi: 10.2174/1389557511313040002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli F, Frasca A, Racagni G, Riva MA. Dynamic regulation of glutamatergic postsynaptic activity in rat prefrontal cortex by repeated administration of antipsychotic drugs. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;73:1484–1490. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani DG, Tabibnia G, Monterosso J, Hellemann G, Poldrack RA, London ED. Effect of modafinil on learning and task-related brain activity in methamphetamine-dependent and healthy individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:950–959. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groc L, Choquet D. AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptor trafficking: multiple roads for reaching and leaving the synapse. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:423–438. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadamitzky M, Markou A, Kuczenski R. Extended access to methamphetamine self-administration affects sensorimotor gating in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;217:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzerling KG, Swanson A-N, Kim S, Cederblom L, Moe A, Ling W, Shoptaw S. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz NA, Lozama A, Prisinzano TE, Carroll ME. Reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking in male and female rats treated with modafinil and allopregnanolone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;100:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss AJ, Gibb JW. Long-term effects of multiple doses of methamphetamine on tryptophan hydroxylase and tyrosine hydroxylase activity in rat brain. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1980;214:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T, Murotani T, Yamatodani A. Action of modafinil through histaminergic and orexinergic neurons. Vitam. Horm. 2012;89:259–278. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394623-2.00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iudicello JE, Weber E, Grant I, Weinborn M, Woods SP HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center, (HNRC) Group. Misremembering future intentions in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2011;25:269–286. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.546812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalechstein AD, De La Garza R, Newton TF. Modafinil administration improves working memory in methamphetamine-dependent individuals who demonstrate baseline impairment. Am. J. Addict. 2010;19:340–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, Green M. Methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment in the initial phases of abstinence. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003;15:215–220. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura O, Wee S, Specio S, Koob G, Pulvirenti L. Escalation of methamphetamine self-administration in rats: a dose-effect function. Psychopharmacol. 2006;186:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Pennay A, Hester R, McKetin R, Nielsen S, Ferris J. A pilot randomised controlled trial of modafinil during acute methamphetamine withdrawal: feasibility, tolerability and clinical outcomes. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Rawson R, Shoptaw S, Ling W. Management of methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandyam C, Wee S, Eisch A, Richardson H, Koob G. Methamphetamine self-administration and voluntary exercise have opposing effects on medial prefrontal cortex gliogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:11442–11450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2505-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandyam CD, Wee S, Crawford EF, Eisch AJ, Richardson HN, Koob GF. Varied access to intravenous methamphetamine self-administration differentially alters adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:958–965. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Bashir ZI. Long-term depression: multiple forms and implications for brain function. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Bashir ZI. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–7828. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh J, Mancino MJ, Feldman Z, Chopra MP, Gentry WB, Cargile C, Oliveto A. Open-label pilot study of modafinil for methamphetamine dependence. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:488–491. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181b591e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Modafinil: a review of neurochemical actions and effects on cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1477–1502. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T-L, Tian Y-H, You I-J, Lee S-Y, Jang C-G. Modafinil-induced conditioned place preference via dopaminergic system in mice. Synapse. 2011;65:733–741. doi: 10.1002/syn.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dell SJ, Feinberg LM, Marshall JF. A neurotoxic regimen of methamphetamine impairs novelty recognition as measured by a social odor-based task. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;216:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsegian A, Glen WB, Lavin A, See RE. Methamphetamine self-administration produces attentional set-shifting deficits and alters prefrontal cortical neurophysiology in rats. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Markou A. Increased motivation for self-administered cocaine after escalated cocaine intake. Neuroreport. 2003;14:2229–2232. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200312020-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Chan CH, Ghee SM, See RE. Sex differences in escalation of methamphetamine self-administration: cognitive and motivational consequences in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2012a;223:371–380. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2727-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Ramsey LA, Schwendt M, Mcginty JF, See RE. Methamphetamine-induced changes in the object recognition memory circuit. Neuropharmacology. 2012b;62:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Schwendt M, McGinty JF, Olive MF, See RE. Loss of object recognition memory produced by extended access to methamphetamine self-administration is reversed by positive allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:782–792. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, See RE. Modafinil effects on reinstatement of methamphetamine seeking in a rat model of relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:337–346. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, See RE. Chronic modafinil effects on drug-seeking following methamphetamine self-administration in rats. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:919–929. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel G, Platt B, Micheau J. Glutamate receptor function in learning and memory. Behav. Brain Res. 2003;140:1–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Santis S, See R. Extended methamphetamine self-administration enhances reinstatement of drug seeking and impairs novel object recognition in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1187-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sase S, Khan D, Sialana F, Höger H, Russo-Schlaff N, Lubec G. Modafinil improves performance in the multiple T-Maze and modifies GluR1, GluR2, D2 and NR1 receptor complex levels in the C57BL/6J mouse. Amino Acids. 2012;43:2285–2292. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1306-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendt MRCM, See RE. Extinction-dependent alterations in corticostriatal metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 and 7 following chronic methamphetamine self-administration in rats. Plos One. 2012;7:e34299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, Meyer RA, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Rev. 2007;17:275–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer J, Darke S, Rodgers C, Slade T, van Beek I, Lewis J, Brady D, McKetin R, Mattick RP, Wodak A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil (200 mg/day) for methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2009;104:224–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon SL, Dacey J, Glynn S, Rawson R, Ling W. The effect of relapse on cognition in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;27:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC, Clark L, Dowson J, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Modafinil improves cognition and response inhibition in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;55:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC, Robbins TW, Clark L, Aron AR, Dowson J, Sahakian BJ. Cognitive enhancing effects of modafinil in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2003;165:260–269. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJMJ, Everitt BJ. Drug seeking becomes compulsive after prolonged cocaine self-administration. Science. 2004;305:1017–1019. doi: 10.1126/science.1098975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci FJ, Appel NM. Approaches to the development of medications for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl. 1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GC, Ricaurte GA, Seiden LS, Schuster CR, Miller RJ, Westley J. Long-lasting depletions of striatal dopamine and loss of dopamine uptake sites following repeated administration of methamphetamine. Brain Res. 1980;181:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H, Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Different contributions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex to recognition memory. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1142–1148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01142.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton EC, Brown MW. Findings from animals concerning when interactions between perirhinal cortex, hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex are necessary for recognition memory. Neuropsychologia. 2009;48:2262–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson HC, Lee ACH. The perirhinal cortex and recognition memory interference. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:4192–4200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2075-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH. Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;329:738–746. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]