Although the ideal for all smokers is to quit completely, a substantial proportion of smokers either do not want to stop smoking or have been unable to do so despite many attempts. Harm reduction strategies are aimed at reducing the adverse health effects of tobacco use in these individuals.

Cutting down

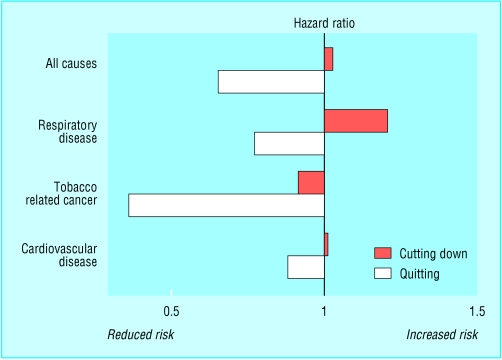

Cutting down on the number of cigarettes smoked each day is a common strategy used by smokers to reduce harm, to move towards quitting, or to save money. Some health professionals also advocate cutting down if smokers cannot or will not stop. No evidence exists, however, that major health risks are reduced by this strategy. The likely explanation for this is that smoking is primarily a nicotine seeking behaviour, and smokers who cut down tend to compensate by taking more and deeper puffs from each cigarette, and smoking more of it. This results in a much smaller proportional reduction in intake of nicotine (and in associated tar and other toxins) than the reduction in number of cigarettes smoked suggests.

Figure 2.

Prospective hazard ratios for death for smokers who cut down or quit compared with continuing heavy smokers. Adapted from Godtfredsen et al (Am J Epidemiol 2002;156: 994-1001)

Cutting down on cigarettes in conjunction with the use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to maintain nicotine levels is a more promising strategy, although NRT is not currently licensed in the United Kingdom or in many other countries for use in this way. Preliminary studies have suggested that this approach may help with sustained cigarette reduction and reduce intake of toxins, but no strong evidence exists yet of health benefit from this strategy.

Switching to “low tar” cigarettes

Many smokers who are concerned about the health effects of smoking switch to “low tar” cigarettes, in the belief that these are less dangerous than ordinary cigarettes. This perception has been encouraged by the tobacco industry and, in many countries, also by government policies seeking a progressive reduction in the tar yields of cigarettes.

Equating low tar with “healthy”: market research for Silk Cut (manufactured by Gallaher)

| “Who are we talking to? The core low tar (and Silk Cut) smoker is female... upmarket, aged 25 plus, a smart health conscious professional who feels guilty about smoking but either doesn't want to give it up or can't. Although racked with guilt they feel reassured that in smoking low tar they are making a smart choice and will jump at any chance to make themselves feel better about their habit” “...white signals the low tar category... low tar (`healthy') quality” |

| Source: House of Commons Health Committee. The tobacco industry and the health risks of smoking. London: Stationery Office, 2000; para 87 (session 1991-200). www.parliament.uk/commons/selcom/hlthhome.htm |

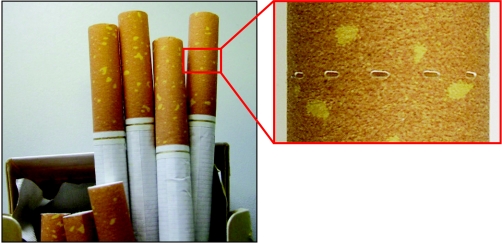

Figure 1.

“Low tar” cigarettes showing ventilation holes in the filters

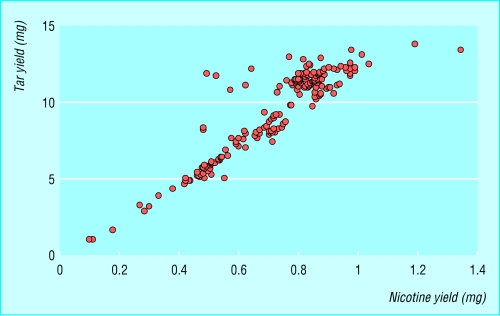

However, tar yields from cigarettes are measured by machines that artificially “smoke” the cigarettes, and much of the reduction in the tar yield of low tar cigarettes, as measured by a smoking machine, results from ventilation holes introduced in the filter to dilute the smoke drawn in by the machine. The ratio of tar to nicotine produced in the tobacco smoke of low tar cigarettes is in fact closely similar to that of conventional cigarettes. Low tar therefore also means low nicotine.

Figure 3.

Tar and nicotine yields for 187 cigarette brands tested by the UK Laboratory of the Government Chemist (data from www.open.gov.uk/doh/dhhome.htm)

Enabling smokers to take control of their cigarette consumption—by using NRT at the same time as cutting down on smoking—may also increase smokers' confidence and ability to quit subsequently

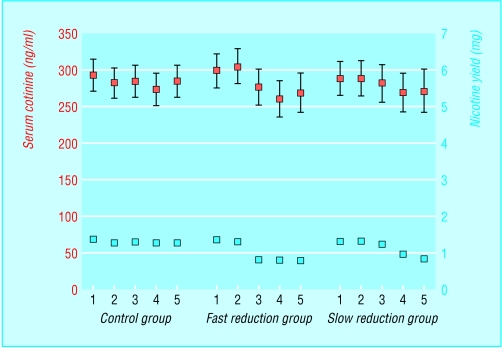

As with cutting down, smokers who switch to lower yield brands tend to compensate for the reduction in nicotine delivery by changing their smoking pattern. With low tar cigarettes smokers do this in two main ways—they smoke the cigarettes more “strongly” by taking more or deeper puffs or they occlude the filter ventilation holes with fingers or lips to prevent or reduce smoke dilution. This results in very little, if any, change in actual intake of nicotine—and consequently of tar—and ultimately therefore, in little reduction in harm.

Figure 4.

Effect of compensation by smokers when smoking low tar cigarettes, as shown by mean blood levels of cotinine (with 95% confidence intervals) and related nicotine yield over time. 1=run-in to study; 2=entry; 3=at 2 months; 4=at 4 months; 5=at 6 months. Adapted from Frost et al (Thorax 1995;50: 1038-43)

Switching to cigars or pipes

Some cigarette smokers, particularly men, switch to smoking cigars or pipes as a means of giving up cigarettes. The risks of smoking cigars or pipes for smokers who have never been regular cigarette smokers are indeed much lower than in former cigarette smokers, principally because they tend not to inhale the smoke but rely on nicotine absorption from the buccal mucosa. Cigarette smokers who switch to cigars or pipes tend, however, to continue to inhale the smoke and are therefore likely to gain little or no health benefit.

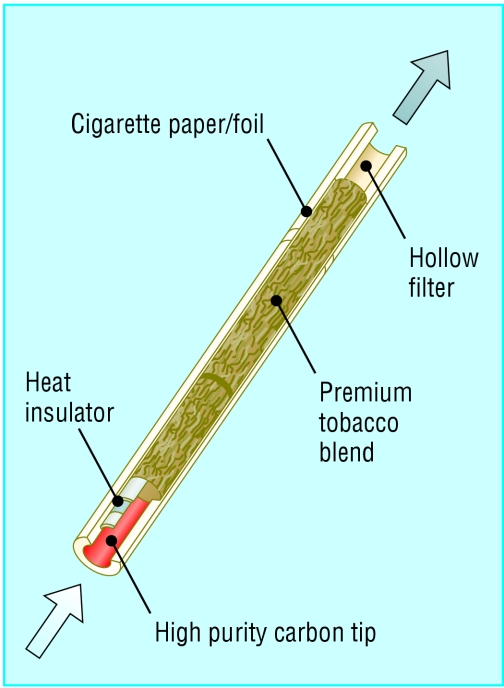

Alternative cigarettes

Several tobacco companies have designed and in some cases marketed alternative smoking products that heat rather than burn tobacco or tobacco products. An example is the Eclipse brand of cigarettes, now marketed in the United States with the claim of being a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes. Eclipse delivers less tar than conventional cigarettes, but more carbon monoxide, so any harm reduction is likely to be limited. No studies have yet shown health benefits associated with switching to Eclipse or similar alternative smoking products.

Figure 5.

According to the manufacturer, R J Reynolds (RJR), Eclipse cigarettes are “designed to burn only about 3% as much tobacco as other cigarettes.” RJR also explains that they “create smoke primarily by heating tobacco rather than burning it” (www.eclipse.rjrt.com)

Switching to smokeless tobacco

Smokeless tobacco comes in two main forms—snuff and chewing tobacco. The types of smokeless tobacco product used around the world vary considerably, as do the health risks across the products used. For example, in India, use of smokeless tobacco is a major cause of oral cancer. Nevertheless the health risks associated with smokeless tobacco are considerably smaller than those associated with cigarettes.

In Sweden the use of oral moist snuff (known as snus) has been common among men for several decades. The health risks of this product seem to be extremely low, in absolute terms as well as in relation to cigarette smoking. Snus seems to be widely used by smokers as an alternative to cigarettes, contributing to the low overall prevalence of smoking and smoking related disease in Sweden.

Snus and other smokeless oral tobacco products currently being developed by some tobacco companies could therefore provide a viable alternative to smoking for many smokers in other countries, and thus deliver substantial health gains. However, these products are currently prohibited throughout the European Union (except in Sweden) on the grounds that they are unsafe.

Figure 6.

Swedish snus, with pound coins for scale

Some experts have argued that even if smokeless tobacco is a less harmful form of nicotine intake than smoking, its availability might have unintended undesirable consequences, such as causing harm to people who might have otherwise quit smoking completely. Other health experts have recommended that smokers should have the right to be able to choose less harmful forms of nicotine delivery, such as snus. They argue that the ban on the less harmful smokeless tobacco products should be lifted—within an evidence based regulatory framework that favours the least harmful forms of smokeless tobacco—and that smokers should be encouraged to use them.

Some experts say that smokeless tobacco may attract more young people to tobacco use and subsequently smoking

Switching to pharmaceutical nicotine products

Switching from cigarettes to pharmaceutical nicotine products—that is, NRT—is standard practice in managing smoking cessation, but these products are not currently licensed for long term use as an alternative to smoking. Given that the risks associated with NRT are much lower than those associated with smoking, long term use of NRT products is a rational harm reduction strategy.

Key points

| • Many smokers try to reduce the harm from smoking by cutting down or switching to “low tar” products |

| • No evidence exists that cutting down or switching to low tar products substantially reduces health risks |

| • Cutting down on cigarettes with concomitant use of NRT could be a more promising strategy |

| • Switching to smokeless tobacco should substantially reduce adverse effects from tobacco use, but in many countries its use is illegal |

| • Switching to pharmaceutical nicotine would substantially reduce harm, but NRT products are licensed as cessation aids, not as substitutes, and smokers tend to find them less satisfying than cigarettes |

| • The regulatory framework in many countries, including Britain, discourages the development of nicotine products that are less harmful than cigarettes |

However, as most smokers do not find the current NRT products to be as satisfying as cigarettes, the viability of these products as a long term substitute is limited. The technology to develop safe, inhaled forms of nicotine that could provide a more satisfactory alternative to cigarette smoking is available in the pharmaceutical industry, but in the context of the current regulatory framework in the United Kingdom and many other countries, such products would not be licensed and are therefore not commercially viable. As discussed above and in the previous article in this series, this imbalance in the regulation of nicotine needs to be redressed urgently in favour of public health.

The ABC of smoking cessation is edited by John Britton, professor of epidemiology at the University of Nottingham in the division of epidemiology and public health at City Hospital, Nottingham. The series will be published as a book in the late spring.

Competing interests: Ann McNeill has received two honorariums and hospitality from manufacturers of tobacco dependence treatments. See first article in this series (24 January 2004) for the series editor's competing interests.

References

- • Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. Regulation of nicotine intake by smokers, and implications for health. In: Nicotine addiction in Britain. London: RCP, 2000. (A report of the Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians, Chapter 6.)

- • Stratton K, Shetty P, Wallace R, Bondurant S, eds. Clearing the smoke: assessing the science base for tobacco harm reduction. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed]

- • Ferrence R, Slade J, Room R, Pope M, eds. Nicotine and public health. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2000.

- • Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians. Protecting smokers, saving lives. The case for a tobacco and nicotine regulation authority. London: RCP, 2002.

- • National Cancer Institute. Risks associated with smoking cigarettes and low machine-measured yields of tar and nicotine. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2001. (Smoking and tobacco control monograph No 13; NIH publication No 02-5074.)