Abstract

Purpose

Our purpose was to understand different stakeholder perceptions about the use of self-monitoring tools, specifically in the area of older adults’ personal wellness. In conjunction with the advent of personal health records, tracking personal health using self-monitoring technologies shows promising patient support opportunities. While clinicians’ tools for monitoring of older adults have been explored, we know little about how older adults may self-monitor their wellness and health and how their health care providers would perceive such use.

Methods

We conducted three focus groups with health care providers (n=10) and four focus groups with community-dwelling older adults (n=31).

Results

Older adult participants’ found the concept of self-monitoring unfamiliar and this influenced a narrowed interest in the use of wellness self-monitoring tools. On the other hand, health care provider participants showed open attitudes towards wellness monitoring tools for older adults and brainstormed about various stakeholders’ use cases. The two participant groups showed diverging perceptions in terms of: perceived uses, stakeholder interests, information ownership and control, and sharing of wellness monitoring tools.

Conclusions

Our paper provides implications and solutions for how older adults’ wellness self-monitoring tools can enhance patient-health care provider interaction, patient education, and improvement in overall wellness.

Keywords: Consumer Health Information, Health Communication, Self Management, Independent Living

1 Introduction

Technological advancements in sensors and networks as well as the wide adoption of mobile devices and personal computers have allowed vast opportunities for personal monitoring tools to emerge. Personal monitoring tools have been broadly explored for older adults, including monitoring in-home movements [1], general health [2], exercise level [3], and general wellness [4].

Wellness is often seen as a critical concept for understanding preventive aspects of disease, disability, and social breakdown [5]. Especially to support older adults, the exploration and assessment of quantified multiple parameters, including physical, social, and mental well-being over long periods of time have been suggested as a necessary area of health research [6]. Demiris et al [7] developed a theoretical framework that guides how informatics applications can support the assessment and visualization of older adults’ wellness. The framework has been validated [8,9]. While studies have widely explored tools for clinicians’ monitoring older adults, we know little about how older adults can self-monitor their wellness and how their health care providers perceive such use of these monitoring tools.

In this paper, we explore and compare older adults’ and health care providers’ perceptions of older adults’ use of wellness monitoring tools. We present our participants’ processes of making sense of a new technology, and we compare common and contradicting perceptions towards the concept of older adults’ monitoring of wellness information. We then propose implications for how wellness self-monitoring tools can be successfully adopted by interested stakeholders and a design that incorporates both participant groups’ needs.

2 Background: Wellness Monitoring

The World Health Organization defines wellness as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity [10].” Hoyman [6] further developed a wellness model suggesting four dimensions that need to be addressed for human health needs: (1) physical well-being/fitness, (2) mental and cognitive health, (3) social well-being, and (4) spiritual well-being. Demiris et al [7] adopted Hoyman’s wellness model and proposed a theoretical framework for developing informatics applications for assessing and visualizing older adults’ wellness. The framework provides how each dimension can be measured and assessed. For instance, physiological and functional well-being can be captured using vital signs, quality of life, and instrumental activities of daily life. Social well-being can be measured using social support and network, and perception of isolation. Demiris and colleagues continued to test the framework through focus groups and demonstration projects [7,11,12] and found that, given appropriate training, older adults showed willingness to participate in technology-enhanced interventions, such as those using personal wellness monitoring tools.

Other researchers have also developed and examined wellness monitoring tools for older adults. For instance, IST Vivago comes in a form of a wristwatch, which continuously monitors physiological signals, movement, and body temperature [13]. It learns users’ normal activities for the first fourteen days of use. Afterwards, for any detection of significant changes, it sends an alarm to an interested party. Using IST Vivago, researchers further validated the feasibility of long-term monitoring of circadian rhythm and sleep/wake patterns of demented and non-demented elderly [14]. Chung et al [15] developed an ECG and tri-axial accelerometer based monitoring tool for use in homecare of older adults. Any abnormal activity will create an alarm which is sent to their health care providers’ personal digital assistant. Adding to the increasing interest of sensor-based technology for older adult care, Alwan [16] conducted field evaluations of pilot studies using sensors in living environments of older adults and found positive acceptance towards monitoring from older adults.

Many studies examined possibilities of using sensing technologies and the Internet to monitor older adults’ wellness in various forms. The common focus in these studies, however, points to mainly how the wellness information can be used by health care providers, not by the older adults themselves. Further studies should examine older adults’ own use of wellness self-monitoring applications, rather than as a passive user unengaged with the system, where the main users are comprised of their health care providers and caregivers. This is especially true given growing evidence showing older adults’ increased use of information technology [17]. Additionally, there is a need to view older adults as a heterogeneous group of individuals differing depending on educational background, economic status, culture, gender and age [18], and not treat them as a unified group.

To address the continuously evolving older adults’ technology use and the increasing opportunities for wellness self-monitoring tools, we build on our existing work [7] to understand how older adults and health care providers perceive older adults’ own use of wellness self-monitoring tools. By self-monitoring, we refer to an activity that users personally monitor their health using any type of technology that provides personal health information. Examples can range from commercially available tools (e.g., Fitbit.com) to use of a personal health record. We further compare findings from older adults and health professional focus groups to understand potential challenges in adopting wellness self-monitoring tools for older adults within their clinical care context.

3 Methods: Focus Groups and Analysis

We conducted three focus groups with health care providers (n=10) and four focus groups with community-dwelling older adults (n=31) to determine participant reactions to potential uses of wellness monitoring tools. Health care providers were recruited through e-mail lists of gerontological/geriatric health care providers within professional networks. Inclusion criteria for health care providers were to have experience in gerontological care. Of the ten health care provider participants, all had professional practice in gerontological care: eight had nursing experience, one was a director of a nursing facility, and one was a geriatric psychiatrist. We conducted three focus group sessions with ten health care provider participants.

Older adult participants were recruited through contact with an activities coordinator at a local retirement facility. Inclusion criteria for older adults were to be a resident of the independent retirement community and be aged 62 years or older. All participants were community-dwelling older adults living independently without skilled nursing care. The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. We conducted four focus group sessions with 31 older adult participants in a community meeting room at the retirement facility.

We explained the nature of the study and facilitated informed consent with each participant before the start of each focus group session. This included providing context to the study through an overview of the health monitoring sources, method of data integration, and Hoyman’s wellness framework. Given the multidimensional nature of wellness and the unfamiliar framework for visualization, we provided examples of each wellness component to study participants (for example, social and spiritual measures were derived from standardized questionnaires, cognitive measures came from brain fitness software, and physiological measures were derived from wireless health monitoring devices). We designed the focus group protocol questions to drive discussion related to perceived value and use of visual displays [19,20] of personal wellness data along with the cognitive processes involved in interpreting the visualizations. The same protocol was used for both sets of participants with minor modifications to fit each group. At the beginning of each session, we introduced the conceptual framework for our visualization work along with contextual information about the data source [7,11]. The moderator then led participants through the visualizations [20], one at a time, providing both a projected view and printout of the displays. The moderator prompted participants based on topics raised in discussion to elicit further views with regard to potential uses of personal wellness data for different stakeholders. Focus groups lasted 60 minutes at most. Each focus group session was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Analysis

From the analysis, we wanted to answer the following question: “How do older adults and healthcare providers perceive older adults’ own use of self-monitoring tools?” To identify the two distinct groups’ perceptions about the value and uses of wellness self-monitoring information, the first author began analyzing the data using open coding analysis [21]. We allowed the codes to continue to evolve as they divided into sub-codes and merged over time. The first author shared the analysis process with co-authors to discuss interpretations and negotiate meaning and application of the codes. After the coding was completed, all authors were involved in the affinity diagramming process of common findings and diverging themes across the codes to come to the final results.

4 Results

From the analysis, we were able to understand older adult and health professional participants’ perceived understanding and potential uses of wellness monitoring tools. We present our findings in four sections, describing the participants’ general perceived use of self-monitoring tools for older adults, their envisioned stakeholders of the tools, perceived control and ownership over wellness information and how the participants perceived sharing wellness information with others accordingly. We first describe older adult focus groups, followed by health professional focus groups. We have summarized the results in Table 1 below.

TABLE 1.

SUMMARY OF THE RESULTS

| Older adult focus groups | Health professional focus groups | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived use of the tool |

|

|

| Perceived stakeholders |

|

|

| Control over wellness information |

|

|

| Sharing wellness information |

|

|

4.1 Older adult focus groups: Struggles and potentials

Older adults generally struggled in making sense of the concept of self-monitoring, but presented insights in various social dynamics around how family members can become stakeholders of older adults’ self-monitoring tools. Older adults showed passiveness in controlling their own wellness information but showed favorable response over sharing wellness information with their health care providers, which they saw as a potential way of increased patient-doctor communication. At the same time, sharing wellness information had some dependencies.

4.1.1 Making sense of self-monitoring

Older adult focus groups generally struggled in making sense of using wellness self-monitoring tools. Older Adult 13’s quote below represents the overall opinions that older adult participants had in terms of how they might use wellness self-monitoring tools—that it is hard to see the advantage of using such tools and understand how such tools would work:

What would be the advantage of it….would a lot of it be guess work? (Older Adult 13)

Specifically, the idea of self-monitoring—the fact that the patients themselves, not their health care providers, would monitor their own health information in an everyday context, not during clinic visits—was an unfamiliar notion for older adult participants. Consequently, older adult participants commented not being able to see the advantage or purpose of using such tools:

Why would [I or doctor] want to know [my wellness information]? (Older Adult 27)

Older adult participants’ understanding of using wellness self-monitoring tools was limited to the context of doctor visits, where the tools would update health care providers about the participants’ health status. For instance, Older Adult 10 perceived that the “ultimate consumer” of the tool would be professionals, not the older adults themselves. Similarly, the Older Adult Group 1 discussed at length how the tool would be used by health care providers. Older Adult 8 mentioned that if older adults can bring the wellness information along to the appointments and showed what they thought were going on, that might help the health care providers.

Furthermore, two older adults (Older Adult 7 and 8) doubted that health care providers would constantly monitor patients’ wellness information in between visits:

Older Adult 7: at the last minute he might use [the wellness self-monitoring tool]. But I don’t think [my doctor would] be looking at it in the interim.

Older Adult 8: But it might be a good way for him to see ‘well this is how you’ve been doing in the interim.’

Older Adult 7: Yeah when you bring it in to [the office].

Older Adult 8: Yeah so you bring it in, [he would know your health status]. Otherwise he wouldn’t know. He may say what happened at this state that caused this to rise you know, was it an emotional one or a physical one or did you eat something you shouldn’t.

The participants in the Older Adult Group 3 showed similar difficulties in envisioning how wellness information can be used in their everyday setting:

Older Adult 21: What I think [the moderator is] saying is […] to see [a printed wellness information] on the shelf outside their door some morning.

[the moderator clarifies that the wellness information will not be printed and put into people’s rooms or shelves]

Older Adult 21: Right.

Older Adult 19: Then what is the idea to do with it?

[the researcher again clarifies that the monitoring tool would be a computer application that is under the participants’ control and their own initiative to start]

Older Adult 19: I don’t have a computer anymore. I needed rebooting and my grandchildren said I needed a new one and I said yes that’s right. And I haven’t gotten it yet. And I probably won’t.

The participants in the Older Adult Group 3 above had a hard time envisioning a computerized tool showing personal wellness information. When a researcher clarified that the information would be shown through a computer, Older Adult 19 responded with a strong aversion to computers.

4.1.2 Perceived stakeholder use

In this section, we describe how older adults perceived each stakeholder would use wellness monitoring tools. Older adult participants generally had little interest for personal use of wellness monitoring tools in an everyday context, but showed good interest for how health care providers and social workers might use such tools to understand patient history. At the same time, the older adult participants had doubts about their health care providers considering such tools as useful. When asked to envision sharing with family members’ use of wellness monitoring tools, older adult participants thought that such tools might be useful depending on the family member. Furthermore, the participants said they would feel comfortable sharing only selective information.

Older adults as stakeholders

In the previous section (4.1.1), we presented that older adult participants had a hard time envisioning themselves monitoring their own wellness with computerized tools. The closest use case they could envision for their own everyday use was a diary, but in a graphical form:

So it could become a graphic diary in fact. (Older Adult 21)

Social workers as stakeholders

One possible stakeholder group beyond health care providers discussed in the older adult focus groups was social workers, who could hear from their patients about improved health (e.g., ‘Look this is how I’ve gone down’ (Older Adult 3)) or problems (e.g., ‘I’m having a problem and it’s self-evidenced by this’ (Older Adult 3)).

Community as a stakeholder

The focus group facilitator posed the idea of wellness monitoring tools installed as kiosks in a community room as a way to also encourage socialization among the community members. Making sense of what a community might be was a challenge for some participants. For instance, Older Adult 12 attempted to ask the definition of a community in comparison to his age group and other demographical context:

Older Adult 12: Well, how am I going to know these things about my community and my age group. How am I going to know who am I covering in this, the whole of {RESIDENCE}, is that my community? Or {NEIGHBORHOOD} you know…

[The researcher explains that the community can be defined by the patient]

Older Adult 12: Right and actually, I don’t think I’m interested.

Furthermore, the Older Adult Group 3 was not keen on the idea of community use and again had hard time grasping the idea, which connects to privacy issues to be discussed in section 4.1.4. The researcher asked how the participants thought of using the monitoring tool as a community. A participant (Older Adult 22) had difficulty envisioning shared use of wellness monitoring tools with the community, mentioning whether the tool would be to understand whether the “politics of the community is going right,” expressing that there are a lot of criteria that he would not be able to understand.

Family members as stakeholders

We also probed how the older adult focus groups would perceive families, or caregivers, could use wellness monitoring tools for their family members. The older adult participants expressed an opinion that how older adults would use such tools together with their family members can depend on who the family members they are sharing with and why. One participant said they would share with their son, but not with others. Another participant pointed out that he would show the information to family members dependent on how well he was doing. Below some threshold of wellness, he preferred not to share the information.

Health care providers as stakeholders

As we found earlier, older adult participants considered health care providers to be the main users of wellness monitoring tools. They furthermore had various perceptions for what kinds of information would health care providers consider as important in understanding and caring patients. Spiritual and social information was a contentious topic about which older adult participants did not agree about the usefulness of the information for health care providers. For instance, the three participants from the Older Adult Group 2 could not agree on whether health care providers would value seeing their patients’ social and spiritual information:

Older Adult 9: Does the healthcare provider usually take into his overview the social and spiritual well-being?

Older Adult 15: They should.

Older Adult 14: I don’t think they [want to see social and spiritual information]

Older Adult 9: I don’t think they touch it….just the physical and cognitive.

Older Adult 15: Maybe you need a new healthcare provider.

Older Adult 9: Or need to talk to a focus group perhaps so healthcare provider…what do you think?

Older Adult 15: Anyone who has suffered through depression certainly needs a healthcare provider who knows what depression means.

Furthermore, Older Adult 9 asked the group if patients bring social and spiritual wellness information to health care providers that would be considered as “bumptious” (Older Adult 9). Similarly, Older Adult 4 discussed emotional information as an important context to share with health care providers.

Beyond whether health care providers would appreciate social and spiritual wellness information or not, older adult focus groups commonly showed unclear perceptions about what health care providers would like to see in wellness monitoring tools and whether provides would be interested at all:

I wonder if he’d want [the tool]. I don’t know. I don’t know how the healthcare provider would say. (Older Adult 8)

I don’t think my Healthcare provider would want to [use wellness monitoring tools] (Older Adult 9)

Stated reasons why older adult participants thought health care providers would not be interested in using the tool was because doctors are busy (Older Adult 8) or doctors already know by statistics when patients will be sick (Older Adult 15).

4.1.3 Controlling wellness information

Older adult participants had a hard time envisioning using wellness monitoring tools for themselves in an everyday setting. Such tools were something that their health care providers would use to monitor them and contextualize their health history. Accordingly, when we continued to probe how older adults would use these tools for themselves, the older adult participants had hard time making sense of how they might control such tools and own the information produced from them. Consider Older Adult 27’s comment:

You would be control of this? (Older Adult 27)

To Older Adult 27’s question, the researcher had to clarify that the older adults would be in control of the tool. A similar situation occurred with another participant in the focus group, where the researcher repeatedly explained that older adults would be in control of the tool, not the health care providers. Also, Older Adult 13 said that he would not be able to understand relationships among his own wellness information unless someone else explained to him:

the connection between my age group and the wellness score, and the size of the circles and the colors, I wouldn’t be smart enough to understand without someone [explaining] (Older Adult 13)

Older Adult 24 also said that older adults would not be able to understand wellness monitoring information as well as researchers would.

4.1.4 Sharing wellness information with others

While self-managing wellness information may be challenging, older adult participants had a positive reaction toward sharing their personal wellness information with their doctors, although they were not sure that their doctors would be interested in seeing the information (Older Adult 27). If the doctors were interested, older adult participants showed a willingness to share their wellness information. Furthermore, the Older Adult Group 2 discussed how sharing day-to-day wellness information would be helpful for the patients themselves since they saw their doctors every six months. Older Adult 8 described wanting to use wellness information as a means to get feedback and further interact with doctors:

if it indicated that something you were doing or not doing was causing a drop or a rise, we could act appropriately or we could consult a health care provider or somebody who takes care of that. But it certainly would help to know if we were heading in the right direction. (Older Adult 8)

Furthermore, the Older Adult Group 1 agreed that sharing wellness information with doctors would be helpful. When the researcher asked whether the participants considered it helpful to show the wellness information to health care providers and start a dialog, most agreed and one stated that he would hope that the health care provider knows it first (Older Adult 7).

Sharing wellness information also involved some dependencies. While sharing wellness information was, in general, acceptable, older adult participants felt uncomfortable sharing negative information about their wellness:

Older Adult 27: [If the tool shows my overall health status is only] sixty percent [well then] you would keep your mouth shut (laughter).

Older Adult 23: No, if it was below fifty percent, yes. Wouldn’t mention a thing to anyone. Like one part of me may point out physical, but, or maybe even social, well, spiritual. [The c]ognitive part—that apparently would be my hardest [one to share] if that was low.

Participants from the Older Adult Group 4 showed above that the cognitive aspect of wellness information would be the most difficult one to share with others. Older Adult 27 expressed that spiritual information is too private to include in a shared wellness monitoring tool.

On the other hand, if participants were to have positive wellness information, they still did not think it would be appropriate to share because “people will know it” (Older Adult 23~25). Older Adult 23 also stressed that “[such tools] would be my own physical being, and I’m doing alright. [Whether] it’s your business or not that’s beside the point. I don’t share that.”

The biggest challenge in thinking about sharing personal wellness information with others came from older adults’ lack of understanding toward privacy protection mechanisms that can exist at multiple levels. For instance, sharing of all information does not necessarily have to be public—one could configure the system so that the information will only be shared to a specific group of people. This notion was difficult to grasp for older adult participants because of their frame of thinking toward how information can be shared through a computer tool:

Older Adult 19: I’m thinking, do you think that this would be passed out to every resident in [Facility A]every month?

[The researcher clarifies that the tool is a computer application]

Older Adult 12: Would it be for management?

[The researcher clarifies that the tool will be for the participants, not for management]

Older Adult 22: Yeah, but, management, if we’re under management, they should know something about this?

Older Adult 21: Why?

Older Adult 19: I mean, you’re going to take something like this and everybody is going to get a copy of it.

[The researcher again clarifies that the idea is not to have the wellness information on a paper but on a computer screen and that the data will be automatically updated]

Older Adult 19: Well, what new data is going to come into it that I didn’t put into it?

Older adult participants in this conversation had hard time grasping the idea that wellness information could be constantly captured and distributed through a computerized system, even though the focus group moderators had explained to them. The notion of “sharing” was handing out printed materials of wellness information to every person in the community. The participants were worried about the spread of information mouth to mouth (Older Adult 26) and how the captured data can be free from a third party accessing the data for secondary use (Older Adult 10).

The lack of confidence shown in our study in understanding wellness information, perhaps combined with already known low comfort levels with computers among some older adults, made it difficult for older adult participants to perceive that they would have control over collecting, analyzing, and acting upon wellness monitoring information. Accordingly, delegating control of their wellness information to health care providers was shown as acceptable, or perhaps helpful use of wellness information, depending on the information itself and the receivers.

4.2 Health professional focus groups: Diverse but limited

Health professional focus groups produced diverse ideas around how the tool can be used by various stakeholders. Although health professional participants had limited understanding towards who will have control over wellness information, they agreed with older adult participants in that sharing wellness information can increase patient-doctor communication.

4.2.1 Perceived use of older adults’ self-monitoring tools

In contrast to older adult participants, health professional participants brainstormed a number of use case scenarios of wellness monitoring tools for older adults, such as patient education, business promotion, problem solving, and patient history tracking.

The participants from three health professional focus groups mentioned wellness monitoring tools as an opportunity to educate older adult patients and caregivers. For instance, Health Professional 10 said that having an “objective measure” could help older adults remind themselves about their wellness during everyday lives:

I think it’s a good tool for teaching. […] it’s nice to have some sort of objective measures of these things because a lot of times we just live our lives day to day. (Health Professional 10)

Similarly, Health Professional 8 also said that such tools can be a great patient and family education tool Furthermore, health professional participants saw that such tools could facilitate “down and dirty” ways of teaching patients by anchoring wellness information as a conversation point between patients and health care providers. Also, having a graphical presentation of wellness information would heighten an easy learning experience for patients:

I used to teach a patient education specialist […] and our little saying is “down and dirty”, just tell them what they need to know, don’t fluff it up. […] people like to hear the information so that they can process it and then formulate their questions and then come and ask you if they needed more information, so this might be a perfect graph for that. (Health Professional 2)

The explicit representation of wellness information in numbers and graph format was perceived as beneficial to educating their patients. However, Health Professional 2 also commented that her staff, who work at a continuing care retirement community who provide living arrangements that range from independent living units to assisted living and skilled nursing services, would have a rather skeptical view towards using such tools with patients and would question whether such an educational scenario would work in practice.

Health Professional 2’s comments about her perception of staff attitudes points to the participants’ viewpoint that different stakeholders may have different model of understanding towards wellness monitoring tools and accepting how the tools could be used (which will be further discussed in 4.2.2).

Another idea that emerged about the potential use of wellness monitoring tools was promoting business. In the Health Professional Group 3, a participant discussed a potential business opportunity for utilizing gathered data for developers to support additional programs for patients’ unfulfilled needs:

This is basically giving you the data to support additional programs, or different directions within the businesses so to me this is powerful data here that could be used [for business]. (Health Professional 7)

Health professional participants also saw wellness monitoring tools as a problem solving tool for older adults. Health Professional 10 mentioned using such tools to aid with older adults’ memory issues:

We live our lives day to day and in my experience a lot of older adults have concerns about their memory. And it’s nice to [test that] really there hasn’t been a significant change in the last two months and reassuring for people. But there have been changes… and that affects … as well. So, I think, I could see it as being sort of a problem solving, a place to problem solve. (Health Professional 10)

Health Professional 2 also discussed that such tools could be used to prioritize care from the health care provider’s perspective:

it’s also cost savings if an RN goes out and understands that there’s really no physical disability, draws some blood, that they’re lonely, there are other interventions that are cost effective that you can do without bringing out more expensive care. So it’s a great way for the clinician to look and see and to prioritize their care as well. (Health Professional 2)

Here, Health Professional 2 describes a use case scenario where a health care provider providing care in patients’ homes could use the tool to prioritize care and to be cost effective.

Lastly, health professional participants saw that wellness monitoring tools could help them track patient history. Health Professional 9 described a tracking application one can use using such tools, where information gathered from the tool could show patients’ wellness changes over time:

if you have a pre data set of ‘this is where they’re at with their cognitive, spiritual, physical needs’ and then you work with them for two more months and you have them do it again and you start tracking changes, you can see where things have improved where they need help and how can you intervene. I feel like the graphs would be useful that way. (Health Professional 9)

Beyond a simple patient history tracking tool, Health Professional 4 further described using personalized scales that the health care provider chose with each patient rather than using well-established scales:

I had a 75 year old woman patient with depression. […E]very week she would come in and I would go through the formal depression criteria. After a while, she told me “Quit asking me all those stupid stuff, what really tells me when I know I’m depressed is when I don’t want to wear bright colored clothing.” It turns out she knows the best measure. […](Health Professional 4)

The same provider proceeded to clarify that patients usually have their own expectations about parameters that need to be monitored for their own wellness and that efforts should be put forth towards identifying shared metrics that would facilitate dialogue and decision making.

4.2.2 Various stakeholders

Health professional participants discussed stakeholder differences with a greater degree of granularity than older adult participants. These participants discussed differences within health care providers and among patient groups. Unlike older adult participants, however, health professional participants did not demonstrate a more detailed understanding for how different family members could use wellness monitoring tools differently.

Family members

Unlike older adult participants, health professional participants had mixed opinions about whether family members of patients would be helpful stakeholders for using wellness monitoring tools. Health Professional 6 noted that patients usually have a better understanding of their own circumstances and needs than family members do:

I don’t think families get it as much as a resident does. […] I think if you had more family education [it would be helpful for both the older adults and the caregivers] (Health Professional 6)

On the other hand, Health Professional 9 shared an opinion that such tools could be helpful for family members who could monitor the progress of the patient, but she was not sure whether the patient would commit to using such tools:

So I feel like the graph could be useful to family members looking and trying to monitor the progress of the patient. So if they’re in a poor spiritual state at the beginning and they are going to work together to go to support groups and go to church together if that’s what they are into then we could show the family members this progress they’ve made in this field and it looks like their quality of life has improved. But I feel like I don’t know that this, an older adult would use it. I feel like family members and health care providers would. (Health Professional 9)

Health Professional 10 verbalized that family members would be interested in overall wellness, rather than the specifics of various wellness information. Health Professional 9 agreed with Health Professional 10:

Yeah, I think that’s kind of what we think. We think how can we help them, whereas I agree with [Health Professional 10] that it seems like the family members just want to know overall, “Are they ok?”. They don’t necessarily need to know exactly what the deficit is as long as their overall health is ok, versus, we’re more concerned about detail. (Health Professional 9)

Here, Health Professional 10 made a distinction between family members and health care providers, where health care providers would be more concerned about detail rather than overall wellness. Health Professional 10 inferred that another reason for such disparity might come from family members who would be overwhelmed by complex detailed information provided by visualizations of wellness data that make them perhaps “confusing for a family member.”

Health care providers as stakeholders

The health professional participants emphasized the different priorities that health care providers have. For example, one health care professional pointed out that older adults may be interested in only one dimension of wellness such as spiritual “and nothing else matters to them except their improving these spiritual needs if that is what that person requires (Health Professional 9)” which may not align with the provider’s priorities of seeking information from multiple dimensions.

Accordingly, determining which aspect of wellness to monitor depends on each health care provider’s priority. Health professional participants delineated differences even among nurses. Health Professional 9 noted that, depending on the nurse, if the nurse is older and not familiar with technology, such nurses might require more guidance in using such tools. Health Professional 9 also speculated that older nurses with lack of experience with computers may not perceive such tools useful and might not use them at all. Health Professional 9 continued to explain the differences among seasoned nurses, younger nurses, and new nurses. Health Professional 9 characterized seasoned nurses as resistant to change:

Seasoned nurses tend to be really resistant to change, resistant to introduction of research and this kind of thing is totally the kind of thing they would like, “I don’t know. I don’t really get it” and it’s fine and when they take the time to explain it, they have already closed the door once. If it’s too confusing they just shut down: “I don’t really need to know it anyways, it’s fine.” Or they require someone to explain it to them even … they don’t understand it. If you come up with something that is easy in the beginning, they don’t feel like they’re behind. They don’t feel like it’s as hard to learn, it’s able to be something that they could utilize. (Health Professional 9)

Older adults as stakeholders

Health professional focus groups in general perceived that older adults would not be interested in using such a tool because these patients would not like “numbers” and too much information. She highlighted that older adults often learn differently:

I guess I’m reluctant to say that older adults would be able to use it. (Health Professional 9)

Even though the example prototypes were born out of previous work with older adults [19,20], health professional participants considered that the information would be too complex for older adults to understand:

I think your older adults would not do well with that. Especially with visual changes and color perception changes they would not do well with. (Health Professional 6)

Health professional participants also pointed out the learning differences among older adults:

when you’re talking about 65 to 75 or 80’s and 90’s, their method of learning is very, very different. You have to worry about color schemes too. Bars might be easiest and they require quite a bit of labeling. (Health Professional 2)

Health professional participants did not consider all older adults as having the same needs. Health professional participants further described patients into multiple user groups. The user groups were: patients in a nursing facility; patients from different generations; and independent community patients. Patients in a nursing facility could potentially be the most active ones as opposed to those in assisted living (Health Professional 6). Health Professional 6 and 8 further discussed how social and spiritual isolation can occur for older adults. Accordingly, for those in close community would be the ones that need the most overall wellness help. Tools that can help monitor wellness levels will be particularly useful for such patient groups as described below:

We at {Facility X}, we are 360 person community. Social isolation and spiritual isolation are very much overlooked in wellness of older adults. And because we are such a close community […] I would use [wellness monitoring tools] to encourage participation in community activities and wellness activities. (Health Professional 6)

For older adults isolated in closed communities, health professional participants discussed how wellness monitoring tools can help older adults to become more active, improving social and spiritual wellness. The differences in where older adults live—assisted living versus independent community—were also perceived as reasons for choosing different design decisions (Health Professional 6). The reason for choosing one or the other is the difference that health professionals saw in terms of the level of social and spiritual activity between independent community members and older adults living in assisted living.

Health Professional 2 pointed out different generations within older adults, which can have different implications for perception and ability that can affect requirements for tool development.

nowadays 65 years old is a young older person, and when you get to 80 things start to change otherwise you’d still feel young. So, be aware that there are different categories and different generations you know of perception and ability. (Health Professional 2)

Staff as stakeholders

Staff members in community housing settings were one of the stakeholders that older adults participants did not discuss. For health professional participants, staff was perceived to have a particular need—to want more detailed information. For instance, pointing to a more complex and complete version of wellness information visualization example, Health Professional 6 said, “Yeah wouldn’t show that to an older adult, I would use that more for staff.” Here, Health Professional 6 implied that older adults should be given a simpler version of the tool containing less information than what staff would use. Health Professional 6’s such opinion was further supported by Health Professional 7, who stated that staff need more specific and larger amount of data:

I think for the older adults they may be confusing, and for the staff and management I don’t think they give them enough data, the specific data or… (Health Professional 7)

Lastly, the following quote from Health Professional 2 shows the importance of noting that a wellness monitoring tool can call for different stakeholders to engage with the older adult depending on the kind of wellness information presented to a team of health care providers:

[do you send out] an RN that’s not advanced practice so they could do the assessment, kind of like home health assessment. You send the RN out first after they’ve already seen the doctor and they decide we can come in. … (Health Professional 2)

4.2.3 Perceived control over older adults’ wellness information

Perceived control and ownership over wellness monitoring information again contradicted in the two participant groups. Older adult participants lacked an explicit understanding that they would control their own wellness information. On the other hand, health professional participants had assumed that health care providers would present wellness information to the patients and adjusting what was presented as needed.

Even though the moderators introduced wellness monitoring tools as something that older adults would use, health professional participants automatically assumed that health care providers would decide which information is shown to older adult patients and when:

you probably wouldn’t want to show [the wellness information] when its going down but you would want to show it [at] the timing when you want to show it to people I think. […] the timing is key for older adults. (Health Professional 7)

As the participants from the Health Professional Group 3 discussed whether health care providers would only show positive information about patients’ status, we could observe the health professional participants’ assumption that they could choose what and when to show the wellness information to their patients. A health professional participant (Health Professional 6) showed an assumption that health care providers will even get to adjust how the information gets presented.

4.2.4 Sharing wellness information among patients and health care providers

Health professional participants concurred with that of older adult participants that patients could use the wellness information as conversation starters where health care providers would ask their patients’ questions. For instance, Health Professional 2 gave an example conversation from a health care provider, such as “Well your spiritual was really good two months ago and look at where it’s at now. Can you tell me what’s going on?” (Health Professional 2)

Health Professional 4 also commented, “Yeah, it’s kind of a starting point for the conversation; it’s not gonna give you anything definitive.” Health Professional 3 further added that wellness monitoring tools could be used to help patients take an active role to continue conversations with their health care providers:

I agree with what both you guys have said, that this information is sort of a jumping off point and then you as the clinician still have to figure out what is actually going on, but I guess this data for me would give me a place to start but it’s really going to be, the patient’s going to determine where I go next. So the patient may look at this data and go oh that’s interesting, lets talk about what’s really going on. (Health Professional 3)

On the other hand, other participants had a more skeptical view about patients who might not be interested in using their wellness information to engage in deeper conversations with health care providers. One participant provided an example where patients potentially may be interested in receiving a medication or other type of treatment to address an immediate need such as a cold rather than engage providers in an in-depth discussion about their quality of life.

Participants further discussed what information might be more appropriate to share than others. Health professional participants discussed, based on their experience, that patients would have diverse attitudes towards sharing wellness information with others. In the Health Professional Group 1’s conversation, Health Professional 9 said certain groups of patients may prefer to just get a drug prescription without extensively discussing their health over the shared wellness data.

5 DISCUSSION

In this section, we discuss how the findings lead to discuss implications for developing wellness monitoring tools for older adults.

5.1 Wellness monitoring tools: a tool to enrich older adult patient-health care provider relationship

The findings showed that older adults participants had difficulty envisioning everyday use of wellness monitoring tools. Health care providers could envision using such tools to help older adults as a more plausible scenario than older adults using such tools on their own. Older adult participants doubted that health care providers would show interest in using such tools. However, health care providers expressed interest in utilizing such tools to enrich patient support in various ways involving multiple stakeholders including staff, primary care doctor, nurses, family members, and patients themselves. Both older adult and health professional participants commented that older adults would find wellness monitoring tools as not useful and potentially too complicated. At the same time, both participant groups agreed that wellness monitoring tools could act as a starting point from which health care providers and older adult patients could build closer relationships through the deeper understanding of the patients’ history.

Given the well-established literature on older adults’ delayed adoption of new technologies [17] and our findings about the contrasting sense of ownership between older adult and health professional participants, the immediate adoption of the self-monitoring tools for older adults may need to be reconsidered. We believe that the discrepancy between our prior work [7] and current work in older adults’ perceived adoption of wellness tools comes from how training can be given before the adoption of the tool and tangible motivations that can be provided for the users. As shown in the literature on prior knowledge and training influencing technology [22,23], a feasible approach might be geared toward a gradual adoption process, where health care providers initially become the main user of collected data from older adults’ electronic medical records. Then the health care providers would begin discussing monitoring results based on the electronic medical records about the past few months together with the older adult during an appointment.

Privacy as it relates to technology that collects health-related data about older adults has been identified as a challenge area in previous research [24–26]. The findings from our study further confirm this challenge. To address privacy concerns and other ethical issues related to technologies that collect health-related data about older adults, efforts to ensure older adults’ understanding of these technologies must be undertaken. As part of these efforts, sources of wellness information need to be transparent to older adults. In addition to facilitation of understanding, such transparency may help increase the sense of information control for older adults. Such interactions could help older adults understand the advantage of interpreting wellness data, and, over time, older adults may gradually become more motivated to use their own data (e.g., personal health records, data collected using sensors at home, manually tracked personal health data), actively collecting data and analyzing their own wellness information. During clinic visits, wellness data, whether coming from electronic medical records or patients’ own monitored data, could be used as conversation starters.

5.2 Personalized sharing configuration for wellness monitoring tools

Considering the findings about issues around sharing, wellness monitoring tools should engage levels of personalization for information presentation based on user roles. As described in the results section 4.1.1, older adults had insufficient idea for where the data come from and who will have access. They also lacked understanding for how much control they would have for the data that they would potentially not want certain stakeholders to have access to (section 4.1.3). As a result, we suggest that further ability to personalize and giving transparency could potentially ameliorate the challenges.

As examples of personalization, depending on the family member and preferences of the older adult, certain information could be hidden. Negative wellness information may trigger unnecessary concern from the family members, while such information may be useful to convey to health care providers or other members of the family. Older adult participants also discussed spiritual information as increasingly personal and we recommend configuring preferences for both monitoring and sharing this information. For those cases where older adults suffer from social isolation, wellness information on social factors may be sensitive information to share with friends, family and the community; although it may also be helpful in encouraging engagement. Furthermore, declining cognitive function can be perceived as stigmatizing to the older adult. Accordingly, wellness self-monitoring tools should ensure user-dependent presentation of wellness information. The tools should provide a configuration interface that older adults can easily express personal preferences for how information should be presented to different audiences.

To reduce the concerns that older adults have towards access of personal wellness information by unwanted audiences, tools should be transparent about who can access information and from where. During the initial adoption phase, making available simulated presentation views for different audiences could help older adults decide how to share their wellness information with others. Also, older adults can click on the monitoring element, which then can show sources of the monitored information.

5.3 Multi-layer design for various stakeholders

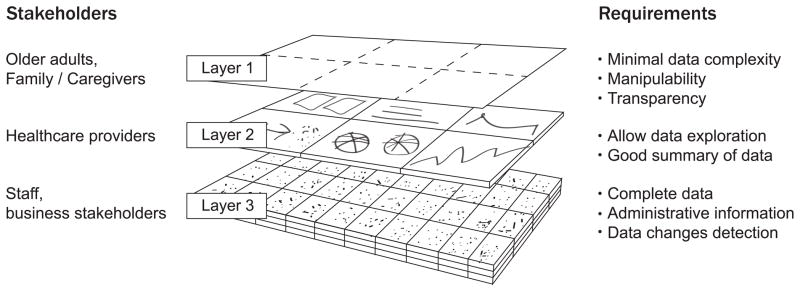

From our findings on perceived roles of various stakeholders, the participants disclosed a number of important insights that can drive not only the interface design but also the system organization, particularly the multi-layered design approach. By multi-layered approach, we mean that a wellness self-monitoring tools provides several layers at which different stakeholders can interact with the tool.

As shown in Figure 1, layer 1 would have a friendly user interface customized to the sharing preference configuration of older adults. The interface at this level should be optimized for older adults and family members’ daily use. The information presented at this level should be highly flexible in hiding information and manipulable for users’ exploration. The source of each element of information should be transparent so as to increase older adults’ control over owning the presented wellness information.

FIGURE 1.

LAYERED DESIGN FOR ADDRESSING MULTIPLE STAKEHOLDER NEEDS

The main user of layer 2 (Figure 1) would be health care providers. Depending on the health care provider and their familiarity with technology, the level of complexity may have to change. In any case, this layer provides users with a data driven interface focused on presenting numbers and ways to detect abnormalities and points of discussion with patients. At the same time, a good summary of trends over time would be helpful for health care providers who may be catching up with a patient’s past history before the appointment.

As one of the health professional participants noted, staff would require complete data, including added administrative information. At this level (Layer 3, Figure 1), the tool will focus on capturing all data changes, such as revisions, additions, and deletions as well as information on any interaction activity with the tool. The data can then be further used to inform patient care or develop as a business opportunity with patient’s consent. While health professional focus groups identified the potentials of using the tools for business opportunities (section 4.2.1), we do not have data for layer 3 as something that patients would allow. The discrepant viewpoints on the business opportunity, or lack of such, leads to one of our main points in the paper on different viewpoints between health professionals and older adults.

The envisioned wellness self-monitoring tool informed by our study presents as a multi-faceted, personalized tool that multiple stakeholders can use for their varying preferences and use cases. The findings suggest that designing such tool to serve beyond self-monitoring could help improve health care provider and patient relationships, create communities, provide business opportunities, and educate patients.

5.4 CONCLUSION

We studied and compared older adults and health professional focus groups’ common as well as contradicting perceptions toward older adults’ wellness self-monitoring tools. We identified some challenges in helping older adults learn new technological concepts and how they may play more active role in owning and controlling their own wellness information. We also found differences between the two participant groups in terms of who can use wellness self-monitoring tools where and how. Such perceptual differences can present challenges in adopting wellness self-monitoring tools as part of the system of caring older adults, where both older adults and health care providers play central roles. We presented implications for how these challenges could be addressed through design and a gradual adoption process.

This study has some limitations. Our older adult participants were recruited from a university affiliated retirement community with residents of higher overall education level. Considering the heterogeneity of older adult population [27], our findings may have limited generalizability. Also, we report participants’ perceptions interpreted primarily by one author, thus our findings may not reflect their actual actions.

Despite the fact that our older adult participants had higher education levels, we found that they experienced challenges understanding the concept of self-monitoring and pursuing an active stance towards owning and sharing wellness information. Such findings could indicate greater technology challenges among the overall population of older adults. As a result, we have presented guidelines to utilize emerging technology for wellness among older adults and suggest ways to improve older adult and health care provider communication.

8 Summary Table.

What was already known on the topic

Many studies found positive potentials in health care providers using sensing technologies and the Internet to monitor older adults’ wellness [3,4,23].

Demiris and colleagues [7,11,12] found that, given appropriate training, older adults showed willingness to participate in technology-enhanced interventions, such as those using personal wellness monitoring tools.

What this study added to our knowledge

We presented older adults’ and health care providers’ contrasting perceptions on older adults’ own use of wellness self-monitoring applications.

We discussed potential advantages in older adults’ voluntary use of wellness monitoring tools and suggested implications for overcoming challenges in adopting the tool.

11 Highlights.

Compared older adults’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions on self-monitoring

Explored advantages in older adults’ voluntary use of self-monitoring

Identified challenges in older adults’ voluntary use of self-monitoring

Suggested design implications for older adults’ self-monitoring tools

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the National Library of Medicine Biomedical and Health Informatics Training Grant T15 LM007442 (which provided support to Dr. Huh and Mr. Le) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Training Grant T32NR007106 (which provided support to Dr. Reeder). We also thank the participants in the focus groups for their contributions.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

Jina Huh conceptualized this study idea and conducted the secondary analysis of the data generating the theme development and the writing of the manuscript.

Thai Le facilitated the focus groups for the parent studies, created visualization prototypes, conducted data collection, transcription and provided feedback on theme development as well as editing of the manuscript.

Blaine Reeder assisted Thai Le with the facilitation of focus groups, note taking and overall data collection. He also provided feedback on theme development and editing of the manuscript.

Hilaire Thompson and George Demiris conceptualized and carried out the parent studies (which provided the secondary data for this study) and provided oversight for Human Subjects Review, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of findings. They also assisted in the writing of this manuscript.

Statement on conflicts of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chung W-Y, Bhardwaj S, Punvar A, Lee D-S, Myllylae R. A fusion health monitoring using ECG and accelerometer sensors for elderly persons at home. Conference proceedings: Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2007. pp. 3818–3821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHorney CA. Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 Health Survey. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:571–583. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson E, Yu F. Monitoring Exercise Delivery to Increase Participation Adherence in Older Adults with Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of gerontological nursing. 2013 Mar;:1–4. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20130313-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rantz MJ, Skubic M, Miller SJ, Galambos C, Alexander G, Keller J, Popescu M. Sensor Technology to Support Aging in Place. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013 Apr; doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn HL. High-level wellness: a collection of twenty-nine short talks on different aspects of the theme. Slack. 1961 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyman HS. Rethinking an Ecologic-System Model of Man’s Health, Disease, Aging, Death. Journal of School Health. 1975 Nov;45:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1975.tb04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demiris G, Thompson HJ, Reeder B, Wilamowska K, Zaslavsky O. Using informatics to capture older adults’ wellness. International journal of medical informatics. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.004. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin CA. Nursing for Wellness in Older Adults. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleffel D. Rethinking the environment as a domain of nursing knowledge. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1991;14:40–51. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization. New York: International Health Conference; 1946. p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson HJ, Demiris G, Rue T, Shatil E, Wilamowska Katarzyna, Zaslavsky Oleg, et al. A Holistic Approach to Assess Older Adults’ Wellness Using e-Health Technologies. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2011;17:794–800. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demiris G, Thompson H, Boquet J, Le T, Chaudhuri S, Chung J. Older adults’ acceptance of a community-based telehealth wellness system. Inform Health Soc Care. 2013;38:27–36. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2011.647938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarela A, et al. IST Vivago®-an intelligent social and remote wellness monitoring system for the elderly. Information Technology Applications in Biomedicine; 4th International IEEE EMBS Special Topic Conference on; IEEE. 2003.2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paavilainen P, Korhonen I, Lötjönen J, Cluitmans L, Jylhä M, Särelä A, Partinen M. Circadian activity rhythm in demented and non-demented nursing-home residents measured by telemetric actigraphy. Journal of sleep research. 2005 Mar;14:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung J, Gassert CA, Kim HS. Online health information use by participants in selected senior centres in Korea: current status of internet access and health information use by Korean older adults. International journal of older people nursing. 2010 Jul;6:261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alwan M. Passive in-home health and wellness monitoring: Overview, value and examples. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zickuhr K, Madden M. Older adults and internet use [Internet] Pew Internet & American Life Project; [cited 2013 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Older_adults_and_internet_use.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selwyn N, Gorard S, Furlong J, Madden L. Older adults’ use of information and communications technology in everyday life. Ageing and Society. 2003;23:561–582. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le T, Demiris KWG, Thompson H. Integrated data visualisation: an approach to capture older adults’ wellness. International Journal of Electronic Healthcare. 2012;7:89–104. doi: 10.1504/IJEH.2012.049872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le T, Reeder B, Thompson H, Demiris G. Health Providers’ Perceptions of Novel Approaches to Visualizing Integrated Health Information. Methods of information in medicine. 2013 Feb;:52. doi: 10.3414/ME12-01-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. Handbook of qualitative research. 1994;273:285. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orlikowski WJ, Gash DC. Technological frames: making sense of information technology in organizations. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) ACM. 1994;12:207. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Free Pr; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demiris G. Privacy and social implications of distinct sensing approaches to implementing smart homes for older adults. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2009. EMBC 2009; Annual International Conference of the IEEE; 2009. pp. 4311–4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demiris G, Doorenbos AZ, Towle C. Ethical considerations regarding the use of technology for older adults. The case of telehealth. Research in gerontological nursing. 2009;2:128. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090401-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zwijsen SA, Niemeijer AR, Hertogh CMPM. Ethics of using assistive technology in the care for community-dwelling elderly people: An overview of the literature. Aging & Mental Health Taylor & Francis. 2011;15:419–427. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.543662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller C. Nursing for Wellness in Older Adults. 6. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2012. Chapter 1: Seeing Older adults through the eyes of wellness; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]