Abstract

Epilepsy is a heterogeneous condition with multiple etiologies including genetics, infection, trauma, vascular, neoplasms, and toxic exposures. The overlap of psychiatric comorbidity adds to the challenge of optimal treatment for people with epilepsy. Seizure episodes themselves may have varying triggers; however, for decades, stress has been commonly and consistently suspected to be a trigger for seizure events. This paper explores the relationship between stress and seizures and reviews clinical data as well as animal studies that increasingly corroborate the impact of stress hormones on neuronal excitability and seizure susceptibility. The basis for enthusiasm for targeting glucocorticoid receptors for the treatment of epilepsy and the mixed results of such treatment efforts are reviewed. In addition, this paper will highlight recent findings identifying a regulatory pathway controlling the body’s physiologic response to stress which represents a novel therapeutic target for modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Thus, the HPA axis may have important clinical implications for seizure control and imply use of anticonvulsants that influence this neuronal pathway.

Keywords: epilepsy, seizures, stress, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, glucocorticoids, hormones, mechanisms, pathophysiology

1. Introduction

Stress, whether it is viewed as physical or psychological, makes most medical illness worse. Stress may be described as an anxiety state, either generalized or situational, and may be associated with psychosocial conditions, psychiatric illness, or the wearying effects of chronic medical illness. Stress worsens psychiatric conditions and contributes to treatment resistance for a wide range of illness including psychosis, mood disorders, and anxiety states. Over the past few decades, the understanding of neurologic and endocrine pathways of stress has exponentially increased and allows sophisticated investigation of brain and behavior relationships.

Many patients with epilepsy report that stress exacerbates their seizures [1–6] (for review see [7]). Anecdotes abound of seizure episodes occurring more often during high anxiety moments or in the context of external stressors that are perceived to be overwhelming [8]. Consistent with the role of stress in epilepsy, basal levels of stress hormones are elevated in patients with epilepsy and are further increased following seizures [9]. Cortisol levels are elevated in patients during the postictal period as compared to control subjects [9–11]. In addition, in a subset of patients with epilepsy, basal plasma cortisol levels are elevated as compared to persons without epilepsy [9, 12]. Furthermore, increased seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy is associated with increased cortisol levels [12]. Despite the intriguing theoretical considerations, the empirical evidence supporting the role of stress in epilepsy has remained controversial. However, today, new investigations may ultimately prove to enlighten clinicians and researchers, who for centuries have been positing stress as causal for seizure episodes.

This manuscript will review the current understanding of the role of stress in epilepsy in both humans and animal models. The current level of understanding regarding the mechanisms underlying how seizures are triggered by stress will be reviewed, and discussion will include speculation of how to prevent seizures from being triggered. Also highlighted are exciting new findings which reveal a novel mechanism controlling the body’s physiological response to stress which may represent a potential target for the treatment of epilepsy.

2. Overview of stress hormone regulation

2.1 The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis

The body’s physiological response to stress is mediated by the HPA axis. A specialized subset of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus controls the activity of the HPA axis. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons release CRH into the hypophyseal portal system which acts in the pituitary gland to signal the release of ACTH. ACTH then triggers the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex in humans (corticosterone in rodents). There are numerous regulatory pathways controlling the stress response. The negative feedback of glucocorticoids is a well characterized mechanism regulating the HPA axis. The classic action of steroid hormones involves binding to steroid hormone receptors, translocation of this ligand-bound receptor complex to the nucleus, and either activation or repression of gene transcription by binding to a glucocorticoid response element in the promoter of glucocorticoid-regulated genes. Glucocorticoid signaling occurs via both a “fast” negative feedback mechanism, which is thought to involve non-genomic actions, and a “delayed” negative feedback mechanism that involves genomic actions (for review see [13]). These effects are mediated by two different types of glucocorticoid receptors, mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs) and glucocorticoid receptors (GRs), respectively [14].

In addition to the negative feedback of glucocorticoids, it is also evident that the HPA axis is regulated by input from numerous different brain regions and neurotransmitter systems (for review see [15]). The prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, amygdala, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BST), and others, influence CRH neurons, either directly or indirectly. The regulatory role of these brain regions is discussed extensively under the “Limbic circuitry and HPA axis regulation” section.

Ultimately, the control of CRH neurons and thus, the HPA axis, is tightly regulated by GABAergic inhibition (for review see [16]). CRH neurons receive robust GABAergic input, and largely originate from GABAergic neurons residing in the anterior hypothalamic area, dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus, the medial preoptic area, lateral hypothalamic area, from multiple nuclei within the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and a local interneuron population surrounding the PVN (peri-PVN). The activity of these neurons is regulated by both tonic and phasic GABAergic inhibition [17–20], highlighting the role of different GABAAR subtypes in the control of these neurons [21] (for review see [22]). GABAA Receptors (GABAAR) and extracellular GABA levels [17, 18] regulate the activity of CRH neurons. Consistent with the importance of GABAergic inhibition in regulating the HPA axis, in humans, GABA agonists have been shown to produce the most robust inhibitory effect on both spontaneous and stimulated HPA axis activity [23].

Numerous GABAA receptor subunits have been identified in the PVN of the hypothalamus, including the GABAAR δ subunit [24] [20]. Interestingly, it was also discovered that there are changes in the expression of extrasynaptic α5- and δ-subunit containing receptors following chronic stress in parvocellular neurons in the hypothalamus [25], implicating extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, including the δ-subunit containing receptors, in stress reactivity. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that CRH neurons are regulated by GABAAR δ subunit-containing receptors which are uniquely sensitive to neurosteroid modulation, including stress-derived neurosteroids (see the sections “Novel therapeutic targets”). These data suggest that extrasynaptic GABAA receptors may be an important target for HPA axis control.

3. Stress and Epilepsy

3.1 A clinical view of stress and epilepsy

The majority of patients with epilepsy identify factors precipitating seizures [26], including sleep deprivation, alcohol intake, menstrual status, and stressful life events. Overwhelmingly, the most common precipitating factor reported is stress, with 30 – 64% of patients reporting feeling stressed prior to seizure occurrence [1–6] (for review see [7]). However, it is also plausible that physiological changes preceding seizure activity induce a feeling of stress in patients with epilepsy, such as in the form of an aura. Although the association between stress and seizure activity is anecdotally widely accepted, it has been difficult to quantify the impact of stress on seizure susceptibility in the human population due, in part, to the vague definition of the word “stress” and the lack of objective measures of stress. Therefore, these studies have largely relied on self-reporting in the human population. These findings remain controversial due to the fact that sleep disturbances, substance abuse/alcohol intake, hyperventilation, and noncompliance with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been identified in association with stress, (for review see [7]) therefore masking the contribution of individual factors. Controlled studies are uncommon, but a few key studies have contributed to the understanding of the relationship between stress and epilepsy.

In an attempt to quantify changes in excitability related to stress, electrographic activity was measured in patients exposed to stressful stimuli. In a classic study, the electrographic activity in patients with epilepsy and individuals without epilepsy was monitored while enduring emotionally stressful stimuli, such as being subjected to a series of accusations and criticisms. Nearly 70% of patients with epilepsy exhibited what the authors referred to as “pathological EEG changes” including exaggeration of spiking, paroxysmal activity, or epileptiform complexes while being subjected to the stressful stimuli [27]. In this study, no epileptiform changes were observed in individuals without epilepsy subjected to these stressors [27]. However, in another study of individuals without epilepsy, subtle EEG changes have been observed, including a narrowing of the bandwidth and regional changes in frequency, in response to stressful verbal stimuli [28]. Strikingly, blind analysis of the EEG recordings correctly identified stressful stimuli responses in 92% of the traces studied [28], demonstrating a characteristic EEG change associated with stress. These studies suggest that stressful stimuli is sufficient to alter electrographic activity in both patients with epilepsy as well as those without epilepsy [27, 28], which may contribute to increased seizure susceptibility when confronted with stressful events.

In a separate study, patients were closely monitored to evaluate seizure occurrence in relation to stressful life events. Patients with a history of four or more seizures per month were monitored by a caregiver recording seizure activity and daily events with no knowledge of the study aims. Temkin et al. discovered that individual patients with epilepsy demonstrated a significant association between seizure frequency and stress, recording that stressful events increased seizures in 58% of patients [29]. These closely monitored case studies suggest that stress may alter excitability and seizure frequency in at least a subgroup of individuals with epilepsy. However, it is important to note that these prospective studies rely on either self-reporting or reporting by a third party which is often limited and variable between individuals studied. Furthermore, these prospective studies can only correlate seizure activity to previous life experiences which may not represent a cause and effect relationship. Despite these limitations, these studies provide a valuable analysis of seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy in relation to daily life stress.

Larger population studies have also been conducted to determine seizure susceptibility in the context of significant emotional and/or environmental stress. The frequency of seizures is increased in high stress environments, such as war-affected regions, compared to patients from low stress, non-war-affected areas [30, 31]. Neufeld et al. conducted a retrospective study of seizure occurrence in Israel during the Gulf War [31]. Patients with epilepsy self-reported an increase in seizure frequency following attacks on Israel in early 1991 during the Gulf War [31]. Similarly, in a retrospective study, Bosnjak et al. studied seizure frequency in children from war-affected regions and non-war affected regions [30]. This study observed an increase in seizure occurrence in children with epilepsy from war-affected regions compared to non-war-affected regions [30]. The authors note that the increased seizure frequency was related to disturbances in waking and sleeping in war-affected regions [30], which is consistent with the impact of stress on seizure susceptibility but may also confound interpretation of these findings. Seizure frequency is also increased in association with the stress of a natural disaster [32]. Swinkels et al. evaluated seizure frequency in flood-affected regions in the Netherlands in 1995 compared to regions unaffected by the floods [32]. This study demonstrates that seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy was increased in flood-affected regions compared to unaffected regions [32]. Interestingly, de novo seizure occurrence was also increased in persons without established epilepsy in flood-affected regions as compared to the unaffected areas [32]. In addition to increasing seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy, several studies suggest that stress may also increase the de novo incidence of seizures in the general population. For example, in a retrospective study, Moshe et al. observed an increase in the incidence of seizures in soldiers assigned to high-stress combat units with no previous history of seizures versus those assigned to low-stress administrative units [33]. This study also attempted to investigate the impact of a stressful environment on seizure incidence in individuals with a history of seizures. Although relatively few soldiers examined in this study had a history of epilepsy, those with known epilepsy had an equal incidence of seizures whether serving in combat units or administrative units [33]. These findings suggest that high-stress environments may independently increase the incidence of seizures beyond the contribution of pre-existing epilepsy. However, it is important to consider that additional factors may contribute to increased seizures in high-risk combat units, such as increased likelihood of trauma and enhanced motivation to report.

Additional studies also support the role of extreme stress in increasing the incidence of de novo seizures. Christensen et al. demonstrate that severe stress resulting from the loss of a child increases the risk for epilepsy [34]. This population-based follow-up study demonstrated a 50% increased risk of epilepsy in parents who lost a child compared to those that did not [34]. However, many of these retrospective studies are limited by the reliance on self-reporting seizure occurrence, which may be biased, and often lack a proper control group. Efforts to directly test the relationship between stress and epilepsy using animal models have served to further elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

3.2 Effects of stress on seizure susceptibility

Some groups have attempted to clarify the role of stress on neuronal excitability and seizure susceptibility using animal models. However, given the bimodal actions of most steroid hormones, including stress-induced steroid hormones, interpreting the effects of stress on seizure susceptibility is complex. Previous studies have generated conflicting results due to differences in the stress paradigms used, duration of the stressors, outcomes measured, and the timing of the stressor in relation to the outcomes measured. For purposes of brevity, this review will explore the current knowledge on the effects of acute and chronic stress on seizure susceptibility in adult animals only and will not address the vast literature on the impact of early life stress (for a review on this subject matter see [35, 36]). Acute stress is defined as a subjection to a single stressful episode; whereas, chronic stress refers to subjection to repeated stressors typically occurring over multiple consecutive days. Furthermore, this section will focus on stress-induced changes in inhibition with a particular focus on brain regions relevant to seizure generation.

Acute stress

Generally speaking, acute stress is thought to be anticonvulsant; whereas, chronic stress is thought to be proconvulsant. Animal models that utilize acute swim stress have been shown to increase the threshold to induce seizures with pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) [37, 38], bicuculline, picrotoxin, strychnine, and 4-aminopyridine [39] (for review see [40]). Similarly, acute cold restraint stress increased the latency to seizure onset induced with PTZ [41]. These studies suggest that acute stress decreases seizure susceptibility which has been proposed to be due to acute stress-induced increased GABAergic inhibition.

Changes in GABAA receptor subunit expression have been demonstrated following acute stress [42], resulting in increased GABAergic inhibition [42]. Specifically, acute CO2 stress increases the expression of the extrasynaptic GABAA receptor δ subunit in the hippocampus and increases tonic GABAergic inhibition, mediated by these receptors, in dentate gyrus granule cells [42]. In addition, acute stress increases the frequency of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) in CA1 pyramidal cells via a GR-dependent, nongenomic mechanism [43]. The stress-induced alterations in GABAA receptor subunit composition and enhanced GABAergic inhibition may explain the decreased seizure susceptibility following acute stress (for review see [40]).

The anticonvulsant effects of acute stress are thought to be mediated by the actions of the neurosteroid allotetrahydrodeoxyorticosterone, THDOC, on GABAA receptors [37] (for review see [44]). Interestingly, neurosteroids act preferentially at δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors [45, 45–49], which are upregulated following acute stress [42]. Neurosteroids are endogenous positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors which can exert profound effects on neuronal excitability. Under physiological conditions, such as in response to acute stress, THDOC levels increase to concentrations sufficient to potentiate GABAergic inhibition [50, 51]. The effects of THDOC on GABAA receptors is thought to underlie the anticonvulsant actions of acute stress [37] (for review see [44]), since THDOC has been shown to exert anticonvulsant effects on PTZ, bicuculline, pilocarpine, maximal electroshock, kindling, kainic acid, and NMDA-induced seizures (for review see [52]).

These data suggest that acute stress is anticonvulsant, which may seem contrary to the observations of increased seizure frequency related to stress in humans. Therefore, it has been proposed that acute stress is protective against seizure events; whereas, chronic stress may be deleterious. Consistent with this theory, chronic stress has been shown to increase seizure susceptibility.

Chronic stress

Surprisingly few studies have directly investigated the impact of chronic stress on seizure susceptibility in adult animals (for review see [53]). Chronic social isolation stress has been shown to decrease the threshold for bicuculline-induced seizures [54]. Similarly, chronic social isolation stress increased seizure susceptibility in response to picrotoxin [55]. These data suggest that chronic stress is associated with increased seizure susceptibility, which may involve numerous pathological changes, including alterations in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission, suppressed neurogenesis, and glucocorticoid-induced hippocampal damage (for review see [56]).

Similar to acute stress, alterations in GABAergic inhibition have been documented following chronic stress. Following chronic social isolation stress, there is increased expression of the GABAA receptor α4 and δ subunit in the CA1 and CA3 region of the hippocampus and in the dentate gyrus molecular layer [57]. These changes are associated with functional alterations in GABAergic synaptic transmission. Chronic restraint stress has been shown to increase the frequency of sIPSCs in CA1 pyramidal neurons [43]; whereas, subjection to chronic mild stress decreases the frequency of sIPSCs in dentate gyrus granule cells [58]. Notably, the most robust effect appears to be enhanced tonic GABAergic inhibition in dentate gyrus granule cells [57, 58]. These data support altered GABAergic inhibition in response to chronic stress; however, enhanced GABAergic inhibition following chronic stress cannot explain the increased seizure susceptibility. However, it is difficult to interpret the cumulative effect of these numerous changes in multiple sub-regions of the hippocampus, some of which may be compensatory physiologic responses.

Chronic stress has also been shown to decrease the brain concentrations of neurosteroids [59, 60], which can dampen the neurosteroid-mediated potentiation of GABAergic inhibition, thereby altering neuronal excitability. Consistent with decreased neurosteroid modulation, chronic social isolation stress induces a decrease in the expression of 5α-reductase, an essential enzyme in the synthesis of neurosteroids [60]. Deficits in neurosteroids following chronic stress may contribute to decreased GABAergic inhibition, which potentially contributes to increased seizure susceptibility. Although the evidence is limited, these findings support the hypothesis that blunted neurosteroid production may be a link between stress and epilepsy.

Chronic stress has also been shown to induce hippocampal damage/remodeling which may contribute to network hyperexcitability (for review see [61]). Multiple chronic stress paradigms have been demonstrated to induce atrophy of dendrites in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (for review see [61]), a region particularly vulnerable to neurodegeneration. In addition, chronic stress suppresses adult neurogenesis (for review see [61]), which may also contribute to changes in network function. Although it is difficult to directly determine the impact of these changes on hippocampal function, it is plausible that these structural changes following chronic stress contribute to hippocampal network hyperexcitability and increased seizure susceptibility.

These findings highlight the opposing effects of acute and chronic stress on seizure susceptibility. Further complicating the effect of stress on seizure susceptibility is the timing of stress in relation to seizure initiation, which significantly impacts seizure susceptibility. It has recently been demonstrated that the latency of seizure induction following stress impacts seizure susceptibility due to actions on mineralocorticoid versus glucocorticoid receptors [62]. Rapid actions of stress hormones (within 30 minutes) on MRs increase seizure susceptibility; whereas, delayed actions of stress hormones (within an hour) on GRs decrease seizure susceptibility in response to kainic acid administration [62]. These findings highlight the complex actions of acute and chronic stress on neuronal excitability.

3.3 Stress hormones and seizure susceptibility

To more directly explore the impact of stress hormones on neuronal excitability and seizure susceptibility, studies have focused upon examining the impact of exogenously administered stress hormones.

Deoxycorticosterone

Deoxycorticosterone (DOC) exerts its effects primarily via actions on mineralocorticoid receptors. In addition, the neurosteroid, THDOC, can be synthesized from deoxycorticosterone, thus implying diverse activities of DOC. The effects of deoxycorticosterone are largely anticonvulsant [37, 63–67]. DOC administration increases the threshold to induce seizures with PTZ, picrotoxin, and amygdala-kindling [37, 63–67]. The anticonvulsant actions of DOC are thought to be mediated by the metabolism to THDOC and the potentiation of GABAA receptors, since the anticonvulsant effects of DOC are abolished by treatment with the neurosteroid synthesis inhibitor, finasteride [37].

Corticotropin-releasing hormone

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) also termed corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) exerts its actions through activation of two subtypes of CRF receptors, CRFR1 and CRFR2. The activity of CRF on these G-protein coupled receptors primarily involves cAMP production (for review see [68]).

Exogenous application of CRH increases the spontaneous firing rate of CA1 pyramidal neurons [69]. CRH also enhances the extracellular field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus [70]. In addition, CRH is also capable of depolarizing CA3 neurons [69, 70] and increasing the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) [70]. Thus, CRH is capable of increasing excitability in multiple sub-regions within the hippocampus.

Furthermore, CRH is sufficient to increase epileptiform activity in the hippocampus [71] and has been shown to induce seizure activity on its own [71–74] (for review see [40]). These data support the theory that CRH is proconvulsant.

Corticosterone

Corticosterone (CORT) exerts its actions through activation of MRs and GRs (for review see [75, 76]). Generally speaking, CORT increases neuronal excitability via rapid actions on MRs and attenuates activity on a longer time scale via actions on GRs (for review see [40]).

Exogenous cortisol administration induces epileptiform activity in response to sub-threshold stimulation [77] and corticosterone increases epileptiform discharges in rats [78]. Corticosterone increases seizure susceptibility to kainite-induced seizures [79], cocaine kindling [80], and amygdala [81–83] and hippocampal kindling [84, 85]. Furthermore, corticosterone has been demonstrated to increase seizures in primates [86]. Consistent with the proconvulsant actions of corticosterone, seizure frequency is highest at the time of day with the highest cortisol secretion [87].

Long term exposure to glucocorticoids, such as what would occur in response to chronic stress, induces neuronal cell loss in the hippocampus [88, 89] which may also contribute to dysfunction in the network activity and hyperexcitability [90]. Glucocortoid-induced cell death is presumed to result from excitotoxicity resulting from enhanced glutamatergic signaling. CORT promotes excitatory transmission in CA1 pyramidal neurons (for review see [40, 91]) and has been shown to increase the frequency of miniature EPSCs in CA1 pyramidal neurons [92]. CORT increases NMDA-mediated responses [93] and increases neuronal burst firing in CA3 pyramidal neurons [94]. These rapid effects of CORT on synaptic transmission are thought to be mediated by MRs [76]. In contrast, CORT actions via GRs result in longer lasting increases in firing frequency accommodation [95, 96].

It is evident that the actions of exogenous stress hormone are proconvulsant, particularly in hippocampal sub-regions. However, the effects of stress hormones in vivo are complicated by the actions of hormones in multiple brain regions, the effects of stress hormones on multiple receptor subtypes, and both the timing and bimodal effects of steroid hormones.

4. Co-morbidity of epilepsy and affective disorders

It is well-accepted that there is a co-morbidity of mood disorders in patients with epilepsy. It is also becoming increasingly clear that these two disorders share a common pathological mechanism. Despite the overwhelming evidence and the significant impact of this co-morbidity on the quality of life of patients [97], few studies focus on investigating the pathological mechanisms of this co-morbidity. Stress is a trigger for both epilepsy and depression and significant accumulating evidence, from both human and animal studies, suggests that the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis may play a role in the co-morbidity of these two disorders [98, 99] (for review see [100]).

4.1 Limbic circuitry and epilepsy

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a common type of epilepsy in which seizures arise from the temporal lobe, including the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and amygdala, all of which are part of the limbic system. Due to the unique neuronal circuitry, the hippocampus seems particularly susceptible to the generation of recurrent seizure activity. Cell loss in the hippocampus has been noted independently in both depression and temporal lobe epilepsy, and may be additive in patients with both conditions [101, 102]. The propensity of seizures to arise from limbic regions may present a direct link between epilepsy and mood disorders.

Limbic regions, in particular the hippocampus, express an abundance of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors [103] and are sensitive to regulation by glucocorticoids. The regulation of these structures by stress hormones may also link stress, seizure susceptibility, and affective disorders. In addition, many of these structures play a role in the regulation of the HPA axis which will be discussed in the sections below.

4.2 Limbic circuitry and HPA axis regulation

The limbic system is involved in the regulation of the HPA axis (for review see [104]). The hippocampus and prefrontal cortex primarily inhibit the activity of the HPA axis; whereas, the amygdala activates glucocorticoid secretion [104–107].

Hippocampus

The hippocampus is most commonly considered to inhibit the HPA axis [106, 107]. Stimulation to the hippocampus decreases glucocorticoid secretion [108, 109] and, conversely, lesions to the hippocampus increase glucocorticoid secretion [88, 110–112] (for review see [104]). Furthermore, the hippocampus has a high density of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors [113–115] further implicating the hippocampus in the negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis (for review see [116, 117]). The hippocampus is a site of remarkable plasticity, including the capacity for neurogenesis in the adult animal. Neurogenesis has been demonstrated to play a role in the regulation of the HPA axis [118, 119]. Conversely, stress and glucocorticoids inhibit adult neurogenesis [120, 121]. These findings suggest that hippocampal neurogenesis may also play a role in the regulation of the HPA axis. Additional findings also implicate changes in neurogenesis with altered HPA axis regulation. For example, loss of GABAA receptor γ2 subunit expression in the adult forebrain results in reduced hippocampal neurogenesis and hyperexcitability of the HPA axis [122]. These studies highlight the importance of GABAergic inhibition in numerous brain regions on HPA axis regulation. Interestingly, neurogenesis has also been implicated in changes in HPA axis regulation associated with depression. The effects of antidepressant drugs may involve enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis and consequent restoration of normal HPA axis function [123]. These findings demonstrate the multifaceted hippocampal-dependent regulation of the HPA axis.

Amygdala

The amygdala plays an important role in emotional processing of stimuli, and is primarily thought to activate the HPA axis. Stimulation of the amygdala increases glucocorticoid secretion [124–126] and lesions to the amygdala reduce glucocorticoid secretion [127–129]. The amygdala expresses a high density of glucocorticoid receptors [130–132] and a lower density of mineralocorticoid receptors [130], implicating the amygdala in the negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis. The amygdala may also influence HPA axis function via connections to other brain regions which exert control over the HPA axis, including the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and other hypothalamic regions.

Medial prefrontal cortex

The role of the medial prefrontal cortex in the regulation of the HPA axis is region-specific, exhibiting topographic differences in regulatory control, which is likely due to differences in anatomical projections. For example, the infralimbic cortex projects to the BNST, amygdala, and the nucleus of the solitary tract, which are involved in activation of the HPA axis. In contrast, the prelimbic cortex projects to the ventrolateral preoptic area, dorsomedial hypothalamus, and peri-PVN regions, which are involved in the suppression of the HPA axis. Furthermore, there is a high density of glucocorticoid receptors in the prefrontal cortex, suggesting that the prefrontal cortex may also be a site of negative feedback regulation of the HPA axis (for review see [104, 133, 134]).

Limbic-HPA axis connections

Despite the clear role of limbic structures in the regulation of the HPA axis, there are few direct connections between limbic structures and the PVN [134]. Limbic regions largely connect to the PVN via relay neurons, which are primarily interneurons in the BNST or peri-PVN region [133, 135]. It is remarkable that the majority of limbic connections onto the HPA axis involve an intermediate GABAergic connection. These findings further demonstrate the importance of GABAergic inhibition in HPA axis regulation.

The importance of limbic regions on the regulation of the HPA axis highlights the relationship between stress and affective disorders. Further, the regulatory influence of limbic regions on HPA axis function may underlie dysregulation of the HPA axis and play a role in the co-morbidity of affective disorders and epilepsy.

4.3 Depression and epilepsy

The overrepresentation of depression in patients with epilepsy is profound. Patients with epilepsy exhibit increased ideation and attempted suicide compared to the general population (for review see [136]). Patients with epilepsy clearly have an increased incidence of mood disorders, but the converse may also be true. Individuals with mood disorders may be predisposed to develop epilepsy or exacerbate the progression of existing epilepsy [137]. It is also becoming increasingly clear that depression and epilepsy may share common pathophysiological mechanisms. A bidirectional relationship between epilepsy and depression has been recently postulated where one condition may exacerbate the other [138]. Despite the considerable impact of this co-morbidity on the quality of life of patients [97], few studies focus on investigating the mechanisms underlying this co-morbidity. Stress is a trigger for both epilepsy and depression and significant accumulating evidence, from both human and animal studies, suggests that the HPA axis may play a role in the co-morbidity of these two disorders [98, 99] (for review see [100]).

A hallmark characteristic of major depression is hyperexcitability of the HPA axis [139–142]. It is generally accepted that major depression is associated with abnormalities in the functioning of the HPA axis and stress exacerbates this disorder [143–149]. Dysfunction in the HPA axis has been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression (for review see [150]) and epilepsy is associated with a dysregulation in the control of the HPA axis [98, 99]. For example, patients with epilepsy exhibit increased circulating levels of ACTH [151], positive DEX/CRH response [98], and increased CORT levels [9–12]. These findings spurred the hypothesis that treatments directed at HPA modulation may have therapeutic potential for the simultaneous treatment of both depression and epilepsy.

Consistent with the overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms underlying mood disorders and epilepsy, treatments for these disorders also exhibit therapeutic overlap. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) typically used as antidepressants also exhibit anticonvulsant properties [152]. Fluoxetine decreases spontaneous seizure frequency in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy [152]. Similarly, citalopram decreases the frequency of spontaneous seizures following kainic acid-induced seizures [153]. The anticonvulsant and antidepressant actions of SSRIs may involve a restoration of normal HPA axis function (for review see [154]) and may be, in part, due to actions on GABAA receptors. SSRIs have been shown to increase neurosteroid levels [155, 156] and normalize stress hormone levels in depressed patients [157]. Restoration of HPA axis function and endogenous neurosteroid levels may play a role in the antidepressant and anticonvulsant effects of SSRIs. The evidence of HPA axis abnormalities in both epilepsy and depression implicate the stress response in the pathophysiology of these disorders, and suggest that HPA axis modulation may be an attractive target for treating both disorders.

4.4 Anxiety disorders and epilepsy

Anxiety is related to epilepsy in numerous ways. Anxiety can be a symptom of the ictal phenomenon, either as a component of a partial seizure or as an aura, in anticipation of a seizure event, as a postictal phenomenon, as an adverse consequence of AED treatment, or as a psychiatric response to having a chronic illness (for review see [158]). Indeed, there is an increased incidence of anxiety disorders in patients with epilepsy [159, 160] (for review see [158, 161]). Seizures arising in limbic regions, such as in temporal lobe epilepsy, are most frequently associated with anxiety, and electrographic recordings support the role of limbic structures involved in anxiety associated with epilepsy [162, 163]. Furthermore, seizure severity is a predictor of anxiety levels [164].

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder resulting as a consequence of experiencing a severe traumatic event, involving the threat of injury or death. Similar to other anxiety disorders, there is also a connection between PTSD and epilepsy (for review see [161]). Sub-convulsive seizures have been associated with symptoms similar to PTSD [165–167]. Long term changes in HPA axis activity have been associated with PTSD and may play a role in the co-morbidity of PTSD and epilepsy. An interesting theory that has been proposed but requires additional investigation is the converse: that anxiety disorders increase the incidence of seizures [160, 168].

5. Treatment for epilepsy

5.1 Current treatment strategies

Patients with epilepsy are treated with a variety of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), although the specific mechanism of action of many of these drugs is largely unknown. Most medication strategies attempt to enhance inhibition, by increasing activity at GABA receptors, or to reduce excitatory activity. Medications to acutely stop seizures such as benzodiazepines and phenobarbital have direct effects upon GABA receptors, prolonging channel openings to various degrees. Anticonvulsant drugs have long been used as primary and adjunctive treatments for mood disorders, most notably bipolar disorder. Efforts to use anticonvulsants for depression and anxiety have also increased over recent years. Ultimately, the mechanisms of anticonvulsants may prove to involve HPA axis modulation either directly or indirectly.

5.2 Therapeutic potential of neurosteroids

Neurosteroids play a prominent role in psychiatric and neurological disorders, including psychotic disorders, alcohol and substance abuse, memory disorders/dementia, anxiety, depression, and epilepsy. Therefore, there has been enthusiasm for neurosteroids for the treatment for a variety of disorders (for review see [163–165]).

Synthetic neurosteroids have been developed which exhibit better bioavailability and efficacy. For example, ganaxolone is a synthetic analog of allopregnanolone and a potent allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors (for review see [169–171]). Mirinus, the pharmaceutical company that developed ganaxolone, has reported positive results in Phase II clinical trials for partial onset seizures and is currently starting clinical trials to evaluate the therapeutic potential of ganaxolone in the treatment of infantile spasms and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [172]. However, clinical trials for a similar compound targeting extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, Gaboxadol, developed by Merck and its Danish partner Lundbeck, have been abandoned due to side effects, including perceptual disturbance and disorientation, as well as lack of efficacy [173, 174]. One of the limitations of neurosteroids as a therapeutic target is the wide distribution of GABAA receptors throughout the brain. Although, neurosteroids act preferentially on a subset of GABAA receptors, the distribution of these receptors in multiple brain regions may result in adverse side effects.

5.3 Therapeutic potential of targeting glucocorticoid receptors

The involvement of the stress response system in numerous disorders, including depression and anxiety, has generated the hope that blocking the physiologic effects of stress may have therapeutic potential. However, blocking the actions of stress hormones is not straightforward. Essential actions of stress hormones on the immune system and metabolic functions have presented obstacles to the successful use of these drugs.

The identification of CRF receptors led to the formulation of CRFR1 antagonists with enthusiasm that these compounds would be beneficial for the treatment of mood disorders, including anxiety and depression. CRFR1 antagonists were successful in decreasing anxiety-like behavior, depression-like behavior, and addiction in animal models. However, CRFR1 antagonists have still not yielded any successful Phase III clinical trials (for review see [175]). Although these compounds were effective in the treatment of depression, anxiety, and addiction in animal models, the clinical trials in humans were abandoned because of potential liver toxicity and limited efficacy. The new perspective on CRFR1 antagonists focuses on the limited use of these compounds for the treatment of dynamic stress disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and panic disorder, rather than chronic conditions such as depression (for review see [175]).

Glucocorticoid antagonists, such as mifepristone (RU-486), have also generated interest as therapeutic candidates for the treatment of stress-induced disorders. One complication of targeting glucocorticoid receptors is that blocking glucocorticoid function results in a compensatory upregulation of other steroid hormones, including ACTH and cortisol [176], which can lead to adrenal insufficiency in some patients [176]. Further, glucocorticoid antagonism also results in suppression of immune function [176]. Mifepristone underwent unsuccessful clinical trials for the treatment of major depression with psychosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (for review see [177]). Due to the complications associated with glucocorticoid antagonists, enthusiasm for directly targeting the HPA axis for treatment has diminished.

Another consideration of glucocorticoid antagonists is that there is a diurnal rhythm of glucocorticoid secretion as well as glucocorticoid release in response to stress. It has been proposed that the mechanisms underlying the pulsatile and circadian baseline release of glucocorticoids are regulated independently [178] and, therefore, theoretically can be modulated independently. It may be possible to develop treatments for modulation of stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion while leaving diurnal glucocorticoid secretion intact. Recent research efforts described below suggests that a novel regulatory mechanism may modulate stress-induced corticosterone release, transiently overriding the circadian rhythmic release.

6. Promising Areas of Research and Young Investigators

6.1 Jamie Maguire

Novel therapeutic targets

Enthusiasm for targeting the HPA axis for therapy has tempered due to the complications described above. However, modulation of the HPA axis for the treatment of stress-related illnesses still remains an intriguing option. CRH neurons, which control the HPA axis, are under robust GABAergic control [179]; however, very little is known about the subtypes of GABAA receptors involved in this regulation. Identification of the subtypes of GABAARs controlling the stress response would have significant therapeutic potential, given that the composition of GABAA receptors dictates the pharmacology, kinetics, and anatomical distribution of these receptors [24, 180, 181]. Therefore, insight into the identity of the GABAA receptor subtypes regulating the HPA axis may reveal potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of stress-related diseases, including, but not limited to, Cushing’s disease, epilepsy, and depression.

Unpublished findings in our laboratory demonstrated alterations in stress reactivity in mice lacking the GABAA receptor δ subunit (Gabrd−/− mice), implicating these receptors in the regulation of the HPA axis. These findings led us to hypothesize that δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors may play a role in the regulation of the stress response. The expression of these receptors in parvocellular neurons in the PVN are altered following stress [25] implicating these receptors in the regulation of the stress response. Given that δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors are sensitive to neurosteroid modulation [47–49, 182, 183], we hypothesized that stress-derived neurosteroid actions on these receptors may be a novel regulatory mechanism controlling the HPA axis.

Our lab recently demonstrated that the GABAAR δ subunit is expressed in the PVN using both Western blot and immunohistochemical techniques [20]. Consistent with the role of these receptors in HPA axis regulation, we demonstrated that CRH neurons are regulated by a neurosteroid-sensitive tonic current which controls the activity of these neurons [20]. Our data demonstrate that, under basal conditions, the firing rate of CRH neurons is decreased by a low concentration (10nM) of the stress-derived neurosteroid, THDOC [20]. Furthermore, the inhibitory actions of THDOC on CRH neurons are mediated by GABAAR δ subunit-containing receptors, since there is no effect of THDOC on CRH neurons from mice lacking the GABAAR δ subunit (Gabrd−/− mice) [20]. These data demonstrate that CRH neurons are regulated by GABAAR δ subunit-containing receptors and implicate these receptors in the regulation of stress reactivity.

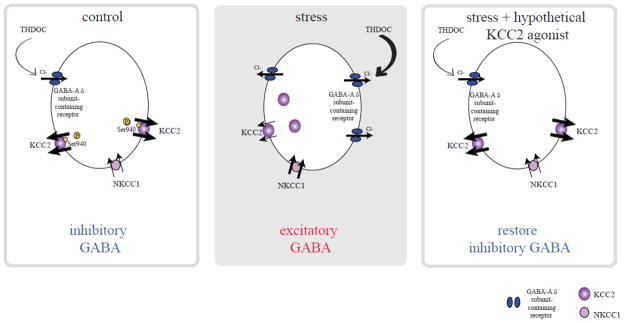

Interestingly, the effects of GABA on HPA axis function are dramatically altered following stress. Stress activates GABAergic neurons which project to the PVN [184, 185] and GABA agonists have been shown to increase circulating corticosterone levels [20, 186]. We recently uncovered a novel mechanism underlying the GABA-mediated activation of the HPA axis following stress [20], involving excitatory actions of GABA on CRH neurons. The inhibitory effects of GABA require the maintenance of the Cl− gradient, which is primarily accomplished by the K+/Cl− co-transporter, KCC2, in the adult brain [187–189]. The function and surface expression of KCC2 is regulated by phosphorylation of KCC2 residue Ser940 [190]. Following stress, there is a dephosphorylation of KCC2 residue Ser940 and downregulation of KCC2, resulting in a depolarizing shift in the reversal potential for chloride (Cl−) [191] and excitatory actions of GABA on CRH neurons [20]. These data demonstrate that cation-chloride transporters play a dynamic role in the regulation of the HPA axis via dramatically altering the effects of GABA. We propose a model whereby in order to overcome the robust inhibitory GABAergic constraint on CRH neurons, KCC2 is rapidly dephosphorylated and downregulated following stress, compromising GABAergic inhibition and enabling the stress response to be mounted (Figure 1). Furthermore, we propose that this mechanism may be unique to stress-induced HPA activation and is independent from the diurnal corticosterone regulation. This is an important consideration in that it may be possible to modulate stress-induced corticosterone secretion without affecting the homeostatic diurnal corticosterone production. Future studies are required to investigate this hypothesis. In addition, these data suggest that cation-chloride co-transporters may be a novel target for modulating the stress response (Figure 1, right panel).

Figure 1. Model of stress-induced HPA axis dysfunction and proposed treatment strategy.

Under basal conditions, KCC2 maintains a low intracellular concentration of chloride, ensuring the inhibitory effects of GABA on CRH neurons (left panel). Following stress, KCC2 is rapidly dephosphorylated and downregulated, resulting in decreased KCC2 function, elevations in intracellular chloride, and excitatory actions of GABA on CRH neurons (middle panel). We propose that theoretical KCC2 agonists would restore low intracellular chloride levels and the inhibitory actions of GABA, which would constrain the HPA axis and be potentially therapeutic for stress-related disorders (right panel). Adapted from [20, 200]. Right panel is based on unpublished findings (Maguire, unpublished data) and speculation based on these unpublished results.

Seizures activate the HPA axis: a vicious cycle?

Epilepsy is associated with a dysregulation in the control of the HPA axis [98, 99]. Patients with epilepsy have increased basal levels of stress hormones and these levels are further increased following seizures [9–12]. Given the pro-convulsant actions of stress hormones (see section “Stress hormones and seizure susceptibility”), it is possible that activation of the HPA axis by an initial seizure event may contribute to future seizure susceptibility. Unpublished findings from our laboratory support this theory; however, future studies are required to fully investigate this hypothesis.

The regulation of stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion involves the dephosphorylation and downregulation of KCC2 in CRH neurons, transiently making GABA excitatory in CRH neurons, to mount the physiological response to stress (see 6.1 Jamie Maguire: Novel therapeutic targets; [20]). Thus, KCC2 may be a novel therapeutic target for HPA axis modulation (Figure 1, right panel). Although there are no currently known KCC2 agonists, such compounds would have therapeutic potential for the treatment of stress-related disorders reviewed in this paper, including anxiety, depression, and epilepsy, as well as neuropathic pain, neurodegeneration, ischemia, and many others (for review see [192]) (Figure 1, right panel). In theory, KCC2 agonists would only affect neurons with deficits in the extrusion of chloride and compromised GABAergic inhibition, leaving neurons with inhibitory GABA rather unaffected. In this way, in the adult, KCC2 agonists would preferentially target neurons in affected regions. This may be why furosemide acts as an anticonvulsant agent [193, 194]. The anticonvulsant effects of furosemide have been proposed to be due to the inhibitory effects on NKCC1 [193, 195]. These data suggest that targeting cation-chloride co-transporters may be useful therapeutic targets.

Consistent with the therapeutic potential of loop diuretics, bumetanide has been shown to have antiepileptic properties in the treatment of neonatal seizures in both humans and rodents [196, 197]. We propose that bumetanide may have antiepileptic effects in adults as well. One of the therapeutic limitations of bumetanide is the limited penetration of this compound into the brain [198]. Following seizures, there is a breakdown of the blood brain barrier (BBB) which may facilitate bumetanide access into the brain, perhaps gaining access preferentially in affected regions. Clearly, additional studies are required to investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting cation-chloride co-transporters in the adult. Interestingly, bumetanide has also recently been shown to exhibit anxiolytic properties [199]. Therefore, targeting cation-chloride co-transporters may have therapeutic potential for treating the co-morbidity of anxiety and epilepsy.

7. Conclusions

Robust evidence suggests that stress and the HPA axis may play a critical role in the pathophysiology of epilepsy. Steroid hormones and brain regions intimately associated with HPA axis regulation may prove to be fundamental mediators not only in epilepsy pathophysiology but also in molecular mechanisms of depression and stress conditions. Stress has long been known to worsen medical illness, and the comorbidity of epilepsy and psychiatric illness associated with stress continues to challenge treatment strategies. Despite the previous obstacles encountered in targeting the HPA axis for treatment, HPA axis modulation remains a compelling therapeutic target. New animal models described above have revealed a novel mechanism regulating stress-induced corticosterone secretion, involving transient excitatory actions of GABA on CRH neurons. It may be possible to specifically modulate stress-induced glucocorticoid secretion without manipulating the basal, diurnal glucocorticoid regulation, which would prevent many of the adverse effects associated with glucocorticoid antagonism. Ultimately, translational efforts may lead to novel treatments that can address clinical conditions that may be more aptly referred to as HPA axis dysregulation.

Highlights.

Emotional stress has long been thought to influence seizure occurrence.

Stress hormones may influence neuronal excitability and seizure susceptibility.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may regulate both stress and seizures.

Aspects of glucocorticoid receptor function may be targets for medications.

Acknowledgments

J.M. is funded by NS073574.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nakken KO, Solaas MH, Kjeldsen MJ, Friis ML, Pellock JM, Corey LA. Which seizure-precipitating factors do patients with epilepsy most frequently report? Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling MR, Schilling CA, Glosser D, Tracy JI, Asadi-Pooya AA. Self-perception of seizure precipitants and their relation to anxiety level, depression, and health locus of control in epilepsy. Seizure. 2008;17:302–7. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neugebauer R, Paik M, Hauser WA, Nadel E, Leppik I, Susser M. Stressful life events and seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1994;35:336–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frucht MM, Quigg M, Schwaner C, Fountain NB. Distribution of seizure precipitants among epilepsy syndromes. Epilepsia. 2000;41:1534–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1499-1654.2000.001534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haut SR, Vouyiouklis M, Shinnar S. Stress and epilepsy: a patient perception survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:511–4. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haut SR, Hall CB, Masur J, Lipton RB. Seizure occurrence: precipitants and prediction. Neurology. 2007;69:1905–10. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000278112.48285.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai CW, Trimble MR. Stress and epilepsy. Journal of Epilepsy. 1997;10:177–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thapar A, Kerr M, Harold G. Stress, anxiety, depression, and epilepsy: investigating the relationship between psychological factors and seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culebras A, Miller M, Bertram L, Koch J. Differential response of growth hormone, cortisol, and prolactin to seizures and to stress. Epilepsia. 1987;28:564–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott RJ, Browning MC, Davidson DL. Serum prolactin and cortisol concentrations after grand mal seizures. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1980;43:163–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.43.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pritchard PB, Wannamaker BB, Sagel J, Daniel CM. Serum prolactin and cortisol levels in evaluation of pseudoepileptic seizures. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:87–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galimberti CA, Magri F, Copello F, Arbasino C, Cravello L, Casu M, et al. Seizure frequency and cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) levels in women with epilepsy receiving antiepileptic drug treatment. Epilepsia. 2005;46:517–23. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.59704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tasker JG, Di S, Malcher-Lopes R. Rapid Glucocorticoid Signaling via Membrane-Associated Receptors. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5549–56. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joels M, Ronald de Kloet E. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in the brain. Implications for ion permeability and transmitter systems. Progress in Neurobiology. 1994;43:1–36. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman JP, Figueiredo H, Mueller NK, Ulrich-Lai Y, Ostrander MM, Choi DC, et al. Central mechanisms of stress integration: hierarchical circuitry controlling hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:151–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman JP, Mueller NK, Figueiredo H. Role of GABA and glutamate circuitry in hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical stress integration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1018:35–45. doi: 10.1196/annals.1296.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JB, Skalska S, Son S, Stern JE. Dual GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in rat presympathetic paraventricular nucleus neurons. J Physiol. 2007;582:539–51. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JB, Jo JY, Zheng H, Patel KP, Stern JE. Regulation of tonic GABA inhibitory function, presympathetic neuronal activity and sympathetic outflow from the PVN by astroglial GABA. J Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park JB, Jo JY, Zheng H, Patel KP, Stern JE. Regulation of tonic GABA inhibitory function, presympathetic neuronal activity and sympathetic outflow from the paraventricular nucleus by astroglial GABA transporters. J Physiol. 2009;587:4645–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.173435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar J, Wakefield S, Mackenzie G, Moss SJ, Maguire J. Neurosteroidogenesis Is Required for the Physiological Response to Stress: Role of Neurosteroid-Sensitive GABAA Receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:18198–210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2560-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stell BM, Mody I. Receptors with different affinities mediate phasic and tonic GABA(A) conductances in hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002:22. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-j0003.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: Phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:215–29. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordano R, Pellegrino M, Picu A, Bonelli L, Balbo M, Berardelli R, et al. Neuroregulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in humans: effects of GABA-, mineralocorticoid-, and GH-Secretagogue-receptor modulation. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6:1–11. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–50. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verkuyl JM, Hemby SE, Joels M. Chronic stress attenuates GABAergic inhibition and alters gene expression of parvocellular neurons in rat hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1665–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spector S, Cull C, Goldstein LH. Seizure precipitants and perceived self-control of seizures in adults with poorly-controlled epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2000;38:207–16. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.STEVENS JR. Emotional activation of the electroencephalogram in patients with convulsive disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1959;128:339–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berkhout J, Walter DO, Adey WR. Alterations of the human electroencephalogram induced by stressful verbal activity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;27:457–69. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temkin NR, Davis GR. Stress as a risk factor for seizures among adults with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1984;25:450–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1984.tb03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bosnjak J, Vukovic-Bobic M, Mejaski-Bosnjak V. Effect of war on the occurrence of epileptic seizures in children. Epilepsy Behav. 2002;3:502–9. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neufeld MY, Sadeh M, Cohn DF, Korczyn AD. Stress and epilepsy: the Gulf war experience. Seizure. 1994;3:135–9. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(05)80204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swinkels WA, Engelsman M, Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenite DG, Baal MG, de Haan GJ, Oosting J. Influence of an evacuation in February 1995 in The Netherlands on the seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy: a controlled study. Epilepsia. 1998;39:1203–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moshe S, Shilo M, Chodick G, Yagev Y, Blatt I, Korczyn AD, et al. Occurrence of seizures in association with work-related stress in young male army recruits. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1451–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen J, Li J, Vestergaard M, Olsen J. Stress and epilepsy: a population-based cohort study of epilepsy in parents who lost a child. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;11:324–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunn BG, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroids and GABA(A) Receptor Interactions: A Focus on Stress. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:131. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koe AS, Jones NC, Salzberg MR. Early life stress as an influence on limbic epilepsy: an hypothesis whose time has come? Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:24. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.024.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy DS, Rogawski MA. Stress-induced deoxycorticosterone-derived neurosteroids modulate GABA(A) receptor function and seizure susceptibility. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:3795–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03795.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pericic D, Svob D, Jazvinscak M, Mirkovic K. Anticonvulsive effect of swim stress in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:879–86. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pericic D, Jazvinscak M, Svob D, Mirkovic K. Swim stress alters the behavioural response of mice to GABA-related and some GABA-unrelated convulsants. Epilepsy Res. 2001;43:145–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(00)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joels M. Stress, the hippocampus, and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:586–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Lima TCM, Rae GA. Effects of cold-restraint and swim stress on convulsions induced by pentylenetetrazol and electroshock: Influence of naloxone pretreatment. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1991;40:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90556-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maguire J, Mody I. Neurosteroid synthesis-mediated regulation of GABA(A) receptors: relevance to the ovarian cycle and stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2155–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4945-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu W, Zhang M, Czeh B, Flugge G, Zhang W. Stress impairs GABAergic network function in the hippocampus by activating nongenomic glucocorticoid receptors and affecting the integrity of the parvalbumin-expressing neuronal network. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1693–707. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy DS. Is there a physiological role for the neurosteroid THDOC in stress-sensitive conditions? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2003;24:103–6. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Houston CM, McGee TP, Mackenzie G, Troyano-Cuturi K, Rodriguez PM, Kutsarova E, et al. Are extrasynaptic GABAA receptors important targets for sedative/hypnotic drugs? J Neurosci. 2012;32:3887–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5406-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stell BM, Brickley SG, Tang CY, Farrant M, Mody I. Neuroactive steroids reduce neuronal excitability by selectively enhancing tonic inhibition mediated by delta subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:14439–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2435457100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mihalek RM, Banerjee PK, Korpi ER, Quinlan JJ, Firestone LL, Mi ZP, et al. Attenuated sensitivity to neuroactive steroids in gamma-aminobutyrate type A receptor delta subunit knockout mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:12905–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belelli D, Casula A, Ling A, Lambert JJ. The influence of subunit composition on the interaction of neurosteroids with GABA(A) receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wohlfarth KM, Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Enhanced neurosteroid potentiation of ternary GABA(A) receptors containing the delta subunit. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22:1541–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01541.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barbaccia ML, Concas A, Roscetti G, Bolacchi F, Mostallino MC, Purdy RH, et al. Stress-induced increase in brain neuroactive steroids: Antagonism by abecarnil. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1996;54:205–10. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Purdy RH, Morrow AL, Moore PH, Paul SM. Stress-Induced Elevations of Gamma-Aminobutyric-Acid Type-A Receptor-Active Steroids in the Rat-Brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88:4553–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogawski MA, Reddy DS. Epilepsy: Scientific Foundations of Clinical Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. Neurosteroids: Endogenous Modulators of Seizure Susceptibility; pp. 319–355. Ref Type: Generic. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popoli M, Yan Z, Mcewen BS, Sanacora G. The stressed synapse: the impact of stress and glucocorticoids on glutamate transmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:22–37. doi: 10.1038/nrn3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chadda R, Devaud LL. Sex differences in effects of mild chronic stress on seizure risk and GABAA receptors in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsumoto K, Nomura H, Murakami Y, Taki K, Takahata H, Watanabe H. Long-term social isolation enhances picrotoxin seizure susceptibility in mice: up-regulatory role of endogenous brain allopregnanolone in GABAergic systems. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:831–5. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mcewen BS. Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serra M, Pisu MG, Mostallino MC, Sanna E, Biggio G. Changes in neuroactive steroid content during social isolation stress modulate GABAA receptor plasticity and function. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holm MM, Nieto-Gonzalez JL, Vardya I, Henningsen K, Jayatissa MN, Wiborg O, et al. Hippocampal GABAergic dysfunction in a rat chronic mild stress model of depression. Hippocampus. 2011;21:422–33. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Serra M, Pisu MG, Littera M, Papi G, Sanna E, Tuveri F, et al. Social isolation-induced decreases in both the abundance of neuroactive steroids and GABA(A) receptor function in rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2000;75:732–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong E, Matsumoto K, Uzunova V, Sugaya I, Takahata H, Nomura H, et al. Brain 5alpha-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone synthesis in a mouse model of protracted social isolation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2849–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051628598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mcewen BS. Stress and hippocampal plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999;22:105–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maggio N, Segal M. Differential corticosteroid modulation of inhibitory synaptic currents in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2857–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4399-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Edwards HE, Vimal S, Burnham WM. Dose-, time-, age-, and sex-response profiles for the anticonvulsant effects of deoxycorticosterone in 15-day-old rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:364–70. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Edwards HE, Vimal S, Burnham WM. The effects of ACTH and adrenocorticosteroids on seizure susceptibility in 15-day-old male rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:182–90. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edwards HE, Vimal S, Burnham WM. The acute anticonvulsant effects of deoxycorticosterone in developing rats: role of metabolites and mineralocorticoid-receptor responses. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1888–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perez-Cruz C, Likhodii S, Burnham WM. Deoxycorticosterone’s anticonvulsant effects in infant rats are blocked by finasteride, but not by indomethacin. Exp Neurol. 2006;200:283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perez-Cruz C, Lonsdale D, Burnham WM. Anticonvulsant actions of deoxycorticosterone. Brain Res. 2007;1145:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eckart K, Radulovic J, Radulovic M, Jahn O, Blank T, Stiedl O, et al. Actions of CRF and its analogs. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:1035–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aldenhoff JB, Gruol DL, Rivier J, Vale W, Siggins GR. Corticotropin releasing factor decreases postburst hyperpolarizations and excites hippocampal neurons. Science. 1983;221:875–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6603658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hollrigel GS, Chen K, Baram TZ, Soltesz I. The pro-convulsant actions of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the hippocampus of infant rats. Neuroscience. 1998;84:71–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00499-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marrosu F, Fratta W, Carcangiu P, Giagheddu M, Gessa GL. Localized epileptiform activity induced by murine CRF in rats. Epilepsia. 1988;29:369–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baram TZ, Schultz L. Corticotropin-releasing hormone is a rapid and potent convulsant in the infant rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;61:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90118-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baram TZ, Schultz L. ACTH does not control neonatal seizures induced by administration of exogenous corticotropin-releasing hormone. Epilepsia. 1995;36:174–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ehlers CL, Henriksen SJ, Wang M, Rivier J, Vale W, Bloom FE. Corticotropin releasing factor produces increases in brain excitability and convulsive seizures in rats. Brain Res. 1983;278:332–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Kloet ER, Joels M, Holsboer F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:463–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Kloet ER, Karst H, Joels M. Corticosteroid hormones in the central stress response: quick-and-slow. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:268–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Conforti N, Feldman S. Effect of cortisol on the excitability of limbic structures of the brain in freely moving rats. J Neurol Sci. 1975;26:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(75)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schridde U, van LG. Corticosterone increases spike-wave discharges in a dose- and time-dependent manner in WAG/Rij rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roberts AJ, Keith LD. Sensitivity of the circadian rhythm of kainic acid-induced convulsion susceptibility to manipulations of corticosterone levels and mineralocorticoid receptor binding. Neuropharmacology. 1994;33:1087–93. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kling MA, Smith MA, Glowa JR, Pluznik D, Demas J, DeBellis MD, et al. Facilitation of cocaine kindling by glucocorticoids in rats. Brain Res. 1993;629:163–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90497-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taher TR, Salzberg M, Morris MJ, Rees S, O’Brien TJ. Chronic low-dose corticosterone supplementation enhances acquired epileptogenesis in the rat amygdala kindling model of TLE. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1610–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edwards HE, Burnham WM, Mendonca A, Bowlby DA, MacLusky NJ. Steroid hormones affect limbic afterdischarge thresholds and kindling rates in adult female rats. Brain Research. 1999;838:136–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kumar G, Couper A, O’Brien TJ, Salzberg MR, Jones NC, Rees SM, et al. The acceleration of amygdala kindling epileptogenesis by chronic low-dose corticosterone involves both mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:834–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Karst H, de Kloet ER, Joels M. Episodic corticosterone treatment accelerates kindling epileptogenesis and triggers long-term changes in hippocampal CA1 cells, in the fully kindled state. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:889–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Edwards HE, Burnham WM, Mendonca A, Bowlby DA, MacLusky NJ. Steroid hormones affect limbic afterdischarge thresholds and kindling rates in adult female rats. Brain Res. 1999;838:136–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ehlers CL, Killam EK. The influence of cortisone on EEG and seizure activity in the baboon Papio papio. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1979;47:404–10. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(79)90156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ehlers CL, Killam EK. Circadian periodicity of brain activity and urinary excretion in the epileptic baboon. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:R35–R41. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1980.239.1.R35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, Mcewen BS. Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure reduces hippocampal neuron number: implications for aging. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1222–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01222.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stein-Behrens B, Mattson MP, Chang I, Yeh M, Sapolsky R. Stress exacerbates neuron loss and cytoskeletal pathology in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5373–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05373.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moghaddam B, Bolinao ML, Stein-Behrens B, Sapolsky R. Glucocortcoids mediate the stress-induced extracellular accumulation of glutamate. Brain Research. 1994;655:251–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Joels M, Pu Z, Wiegert O, Oitzl MS, Krugers HJ. Learning under stress: how does it work? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Karst H, Joels M. Corticosterone slowly enhances miniature excitatory postsynaptic current amplitude in mice CA1 hippocampal cells. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3479–86. doi: 10.1152/jn.00143.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kole MH, Swan L, Fuchs E. The antidepressant tianeptine persistently modulates glutamate receptor currents of the hippocampal CA3 commissural associational synapse in chronically stressed rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:807–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Okuhara DY, Beck SG. Corticosteroids influence the action potential firing pattern of hippocampal subfield CA3 pyramidal cells. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;67:58–66. doi: 10.1159/000054299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Joels M, de Kloet ER. Effects of glucocorticoids and norepinephrine on the excitability in the hippocampus. Science. 1989;245:1502–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2781292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kerr DS, Campbell LW, Hao SY, Landfield PW. Corticosteroid modulation of hippocampal potentials: increased effect with aging. Science. 1989;245:1505–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2781293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boylan LS, Flint LA, Labovitz DL, Jackson SC, Starner K, Devinsky O. Depression but not seizure frequency predicts quality of life in treatment-resistant epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;62:258–61. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000103282.62353.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zobel A, Wellmer J, Schulze-Rauschenbach S, Pfeiffer U, Schnell S, Elger C, et al. Impairment of inhibitory control of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical system in epilepsy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:303–11. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mazarati AM, Shin D, Kwon YS, Bragin A, Pineda E, Tio D, et al. Elevated plasma corticosterone level and depressive behavior in experimental temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:457–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]