Abstract

Cell death is a stochastic process, often initiated and/or executed in a multi-pathway/multi-organelle fashion. Therefore, high-throughput single-cell analysis platforms are required to provide detailed characterization of kinetics and mechanisms of cell death in heterogeneous cell populations. However, there is still a largely unmet need for inert fluorescent probes, suitable for prolonged kinetic studies. Here, we compare the use of innovative adaptation of unsymmetrical SYTO dyes for dynamic real-time analysis of apoptosis in conventional as well as microfluidic chip-based systems. We show that cyanine SYTO probes allow non-invasive tracking of intracellular events over extended time. Easy handling and “stain–no wash” protocols open up new opportunities for high-throughput analysis and live-cell sorting. Furthermore, SYTO probes are easily adaptable for detection of cell death using automated microfluidic chip-based cytometry.

Overall, the combined use of SYTO probes and state-of-the-art Lab-on-a-Chip platform emerges as a cost effective solution for automated drug screening compared to conventional Annexin V or TUNEL assays. In particular, it should allow for dynamic analysis of samples where low cell number has so far been an obstacle, e.g. primary cancer stems cells or circulating minimal residual tumors.

Keywords: SYTO, Apoptosis, Kinetic assays, Antitumor drugs, Microfluidics, Lab-on-a-Chip, Flow cytometry

Introduction

We are now facing the era of large compound libraries and novel screening platforms, using microfluidic microchip and Lab-on-a-Chip devices. High-content analysis (HCA) is being recognized as a key component in the anti-cancer drug discovery pipelines, and is most commonly used for estimation of drug cytotoxicity [1]. However, dynamic high-throughput analysis of cell death is often limited by excessive probe cytotoxicity [2]. Indeed, supravital analysis of intracellular processes, especially in long-term, requires biomarkers that do not interfere with structure or function of the cell. Indeed, most cell permeant fluorescent probes developed to date, including Hoechst 33342, DRAQ5 or Vybrant DyeCycle Orange, lack this feature [2,3]. We have recently reported that cyanine SYTO probes rapidly diffuse through eukaryotic membranes [1,4], and are applicable for many polychromatic assays in studies of caspase-dependent cell death [4,5]. Here, we introduce innovative SYTO-based assays for kinetic tracking of apoptosis, that meet the following criteria of dynamic and high-throughput analysis, namely: (i) the straight-forward staining and adaptability for automated dispensing; (ii) the prolonged intracellular retention, (iii) the lack of side-effects on cellular viability, proliferation or cell migration; and (iv) the lack of interference with the assay readout.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The culture of human B-cell lymphoma and leukemic (HL60, U937) cell lines were as previously described [4,5]. Human osteosarcoma U2OS cells were from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). The following inducers of apoptosis were used: dexamethasone (Dex; 1– 1000 nM); cycloheximide (CHX; 0–10 µg/ml); staurosporine (STS; 0.1–1 µM); and camptothecin (CAM; 1–10 µM), all from Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis MO, USA).

Staining with SYTO dyes

Labeling with SYTO green (SYTO 11–16) and SYTO red (SYTO 17, 59–64) probes (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) was performed as described earlier [1,4,5]. Staining with SYTOX green (30 nM), SYTOX red (10 nM) or YO-PRO 1 (250 nM) was performed as previously described [6,7].

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Flow cytometry was performed using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), equipped with a 15 mW Argon-ion and 20 mW red diode lasers served as a reference instrument. Logarithmic amplification scale using following configuration of band-pass (BP) filters was applied: (i) 488 nm excitation line: FL1 (525 BP for collection of: SYTO green, SYTOX green, YO-PRO 1 fluorescence signals) FL 2 (575 BP for collection of: PI fluorescence signal); and (ii) 635 nm excitation line: FL4 (675 BP for collection of: SYTO red, SYTOX red fluorescence signals).

Sorting of respective subpopulations was performed on EPICS Elite ESP (Coulter Corp., Miami, FL, USA) cell sorter, equipped with 15 mW air-cooled Argon-ion laser operating at 488 nm excitation line. A 525 BP (SYTO16), 610 BP (PI) band-pass filter was used.

Sort gates were drawn on bivariate SYTO 16/PI dot plots around two distinct subpopulations: SYTO16high/PI− (deemed live cells), SYTO16dim/PI− (deemed early apoptotic cells). To avoid destruction of sorted apoptotic subpopulations system pressure operated at 10 PSI and sort rates did not exceeded 3000 cells per second. All cell-sorts were performed using Purity1Recovery2 sort mode (Coulter) which allowed achieving≥95% cell purity for each subpopulation [4].

Cell co-culture experiments

To assess cellular leakage of SYTO probes, U937 or HL60 cells were labeled with cyanine SYTO probes, as follows: (i) no label; (ii) SYTO 16; (iii) SYTO 62; (iv) SYTO 16+SYTO 62. Next, cells were washed extensively with PBS to remove any residual and unbound SYTO molecules, and resuspended in fresh RPMI medium. All the samples were combined, seeded on 24-well plates, and analyzed by flow cytometry, as described above, at the indicated time points.

For cell imaging, U2OS cells were seeded on optical plates at a density of 2.5×105 cells/ml. After an overnight culture, cells were rinsed with PBS, and U937 cells (5×105 cells/ml) pre-labeled with SYTO 16 or SYTO 62 were seeded onto the monolayer of U2OS cells. After 24 h co-culture, cells were analyzed using a motorized Axiovert 200 M microscope(Zeiss), equipped with an AxioCam HRc CCD camera (Zeiss) and HBO100 lamp. Images were analyzed using ImageJ (freely available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ web page).

Microfluidic chip-based cytometry

We used a microfluidic system based on Caliper LabChip® technology (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA), utilizing disposable chips run by a modified Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). This technology allowed simultaneous analysis of up to six independent samples with a throughput of about 2.5 cells/second. For on-chip cytometry, cells were stained with SYTO 16 as described earlier [4,5]. Next, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 100 µl of isobuoyant buffer (Agilent). An equivalent of 2×104 cells (10 µl) was loaded to each sample well. In some experiments the on-chip staining protocol was employed, with SYTO and SYTOX probes diluted in isobuoyant buffer and added directly to chip wells loaded with cells. The chips were run according to manufacturer's instructions, and data was acquired with Agilent 2100 Expert Software (Agilent). Data was then converted to FCS2.0 standard, and analyzed offline using WinMDI 2.8 software.

Data and statistical analysis

Data analysis and presentation was performed using Summit v3.1 software (DakoCytomation, Fort Collins, CO, USA) and open access WinMDI ver.2.8 (http://facs.scripps.edu/software.html). Student's t-test was applied for comparison between groups, and differences were considered significant at p< 0.05 (SigmaPlot 8.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Most SYTO probes lack short-term and long-term cytotoxicity

Assessment of thirteen SYTO probes on a panel of hematopoietic and epithelial tumor cell lines revealed that both green and red fluorescent probes are well-retained within the cells during short-term cell culture (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1), and with the exception of SYTO 15 do not induce cell death (Fig. 2A). We noted a significant heterogeneity in retention between different SYTOs, ranging from 4.3% (SYTO 62) to 38.2% (SYTO 16) at 72 h post-labeling. This reflects the structural heterogeneity between the probes, resulting in divergent accumulation to subcellular compartments, as recently described by us for SYTO orange dyes [1]. Clearly, substantial loss of the SYTOs over 48 h of incubation was significantly greater than one would expect from a covalent binding dye such as CFSEDA or a membrane probe such as PKH26. The retention of SYTOs is generally short-lived and observed predominantly in the first 24 h (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, in contrast to carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), cell divisions do not cause a gradual loss of SYTO fluorescence. Recent report have also shown that SYTO probes are effective substrates of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump and its inhibition (e.g. by Verapamil hydrochloride) is necessary to preserve SYTO staining in cells expressing ABC transporters [1,4]. As all our experiments were performed in the presence of P-glycoprotein inhibitors (Verapamil hydrochloride and Probenecid, 30 µM), we anticipate that loss of SYTO staining represents a gradual, passive leakage of fluorescent probes rather then an active, ATP-dependent efflux [1,4].

Fig. 1.

Intracellular retention of green and red fluorescent SYTO probes: Human B-cell lymphoma cells were pre-stained with 100 nM of SYTO 11/16/62 for 20 min at RT. Following incubation, cells were washed and cultured in dye-free medium for the time indicated. Filled histograms denote unstained control cells. A, B, C, and D denote: 0, 24, 48, 72 h of post-staining culture, respectively. Note that apart from retention heterogeneity all probes were sufficiently retained in live cells after 24 h to allow gating of tagged subpopulation. Results are representatives of four independent experiments. Similar data were obtained on U937 and HL60 cells.

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxicity of substituted cyanine SYTO probes: (A) Influence of SYTO probes on cell viability. Human B-cell lymphoma cells were pre-loaded with 250 nM of selected dyes as described before. Following incubation, cells were washed and cultured in dye-free medium for 48 h. Cell viability was estimated by staining with SYTOX Green (for SYTO 17–62) or SYTOX Red (for SYTO 11 –16) stains. Note that all but SYTO 15 probes do not affect cell viability. Similar results were achieved when cells were continuously challenged with 250 nM of SYTO probes (not shown). Results are representatives of four independent experiments; (B) Influence of SYTO probes on cell cycle progression. Human B-cell lymphoma cells were pre-loaded with selected dyes as described in (A). Cells were then washed and cultured in dye-free medium for 48 h. Cells were subsequently collected and fixed in 70% EtOH for 2 h. Cell cycle analysis was performed using standard PI staining protocol. Note lack of cell cycle disturbances and sub-G1 peak following SYTO pre-loading. Similar results were obtained when cells were continuously cultured in the presence of SYTO dyes (not shown). Results are representatives of four independent experiments; SD values were lower than ±6 for each phase of the cell cycle; (C) Influence of SYTO probes on DNA replication. DNA synthesis (deemed as cell proliferation) was assessed using [methyl-3H]-thymidine incorporation assay 24 h after SYTO staining. Results represent mean (±SD, n=3) of [methyl-3H]-thymidine incorporation relative to untreated controls. Note disturbance of DNA replication for only SYTO 15 stain (p < 0.05). Similar results were achieved when U937 and HL60 cells were continuously cultured in the presence of up to 1 µM of selected SYTO probes (not shown); and (D) The influence of SYTO probes on cell growth. Lymphoma cell lines were treated with indicated SYTO dyes at 250 nM, and the number of viable cells was assessed using standard Trypan Blue assay during the 3-day study. Note cell growth disturbance for SYTO 15 (p<0.05). The results represent mean of at least three independent experiments; normalized SD values were lower than ±3.

It should be stressed that, SYTO probes, whether pre-loaded or present continuously in cell culture media did not affect cell cycle, and, except SYTO 15, short-term cell proliferation or long-term cell growth (Figs. 2B–D and data not shown). In addition, SYTO 16 and SYTO 62 had no effect on directional cell motility, as shown in the wound-closure assay using invasive breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Dynamic quantification of apoptosis with SYTO probes

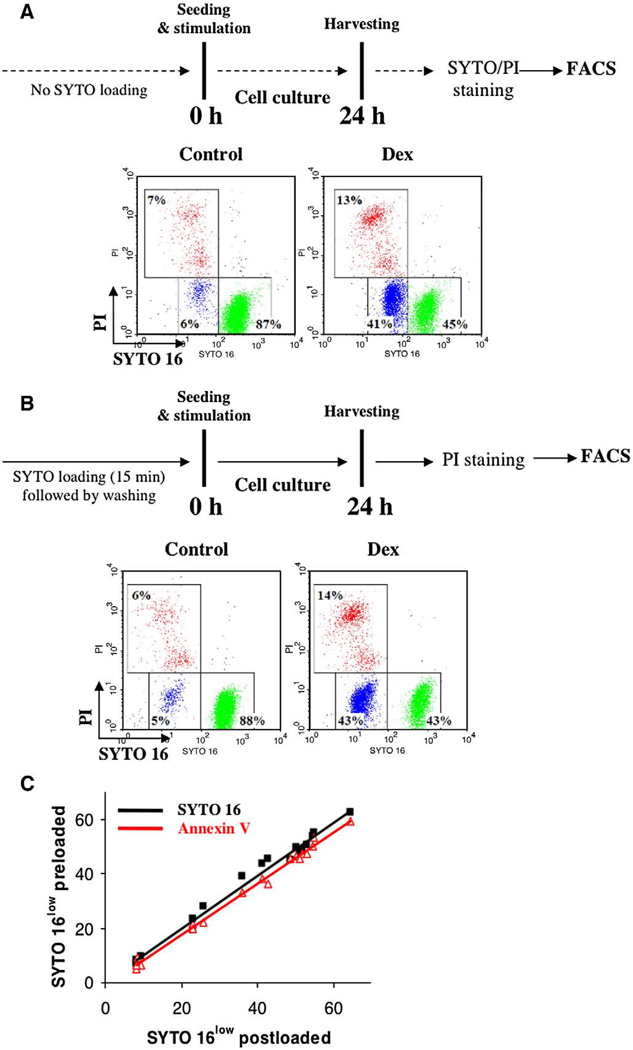

Based on these observations, we determined the applicability of inert SYTO16, a sensitive marker of caspase-dependent cell death [4,5,8], for dynamic, real-time quantification of apoptosis. Human B-cell lymphoma cells were exposed to a panel of apoptosis inducers (dexamethasone, anti-CD95 agonistic antibody, cycloheximide) for up to 24 h, followed by SYTO16/PI staining at the end of experiment (end-point assay) (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Alternatively, cells were pre-loaded with 250 nM SYTO 16, washed, seeded in SYTO-free medium with or without the indicated inducers of apoptosis, and labeled with PI at the end of experiment (dynamic assay) (Fig. 3B, upper panel). Under normal culture conditions, a small fraction of apoptotic cells could be detected, with both assays showing comparable sensitivity (6±2% end-point SYTO 16 vs. 5±1% dynamic SYTO 16; Figs. 3A and B). Upon treatment, end-point and dynamic SYTO16 assays again gave similar estimates of the three cell populations, live, apoptotic, and late apoptotic/necrotic (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, both assays had comparable sensitivity over a broad range of stimuli and exposure times (R2≥0.96 for p<0.05 in Pearson and Lee linear correlation test), and yielded similar results to the end-point Annexin V/PI assay (R2≥0.97 for p <0.05) (Fig. 3C). Pertinent to HCA of cytotoxic drugs, the dynamic SYTO 16 bioassay can be further improved by combining low doses of SYTO and plasma membrane permeability markers (Supplementary Fig. S2, protocol II).

Fig. 3.

– Dynamic quantification of apoptosis using SYTO probes: (A) Human B-cell lymphoma cells were exposed to a pro-apoptotic drug dexamethasone (Dex; 1 µM) for 24 h. After stimulation cells were collected and stained according to a standard SYTO 16/PI protocol (end-point assay, upper panel). Data were acquired using FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with 488 nm excitation line and standard optical filter configuration. Green events (R1; SYTOhigh) – live cells, Blue events (R2; SYTOlow) – apoptotic cells, Red events (R3; SYTOlow/PI+) – late apoptotic/necrotic cells; (B) As in A) but cells were pre-loaded with 250 nM of SYTO 16, washed, seeded in SYTO-free medium with or without the indicated apoptotic stimuli, and labeled with PI at the end of experiment (dynamic assay, upper panel). Note excellent agreement between results obtained with end-point (A) against dynamic protocols; and (C) Sensitivity of dynamic SYTO assay. Cells were treated with dexamethasone (0–1000 nM) and cycloheximide (0–10 µg/ml) for 6–72 h. After stimulation parallel samples were collected and processed separately according to end-point (SYTO 16 post-loaded) or dynamic (SYTO 16 pre-loaded) protocols. Note comparable sensitivity for both assays over a broad range of stimuli and exposure times (R2≥0.96 for p < 0.05 in Pearson and Lee linear correlation test). For comparison, data from the Annexin V/PI assay were superimposed (red) and indicate exceptional sensitivity of both SYTO 16 assays (R2≥0.97 for p < 0.05). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In this simplified no-wash protocol, cells were simultaneously labeled and treated with apoptotic drugs, and at the end of experiment immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (end-point staining as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, protocol I, was used as a reference). The low-dose continuous labeling procedure not only provided similar results to a standard end-point staining protocol (Supplementary Figs. S2B and S2C), but also allowed a straightforward adaptation for high-throughput screening. Interestingly, and in contrast to other reports, cells incubated in the presence of PI were viable even after 72 h. Although PI fluorescence in these cells was greatly elevated, the cells did remain viable, as evidenced by counterstaining with SYTOX Red dye and retained their proliferative potential (data not shown). To circumvent elevated fluorescence signal 10-fold reduced concentration of PI was employed in the no-wash HTS protocol without compromising assay's sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. S2).

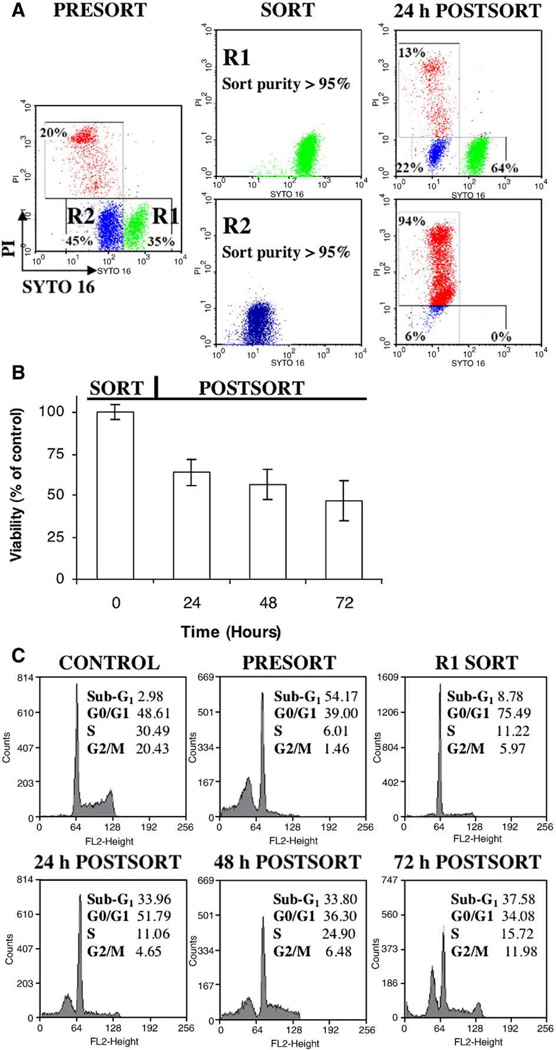

SYTO probes allow for a live-cell sorting but not a prolonged cell tagging

Live cell sorting and cell tagging can provide additional information on the stochastic process of cell death, including analysis of post-treatment or by-stander cytotoxic events, and cell multiplexing [9,10]. To ascertain whether dynamic SYTO 16 assay can be used for live-cell sorting, human B-cell lymphoma cells were loaded with SYTO 16, treated with Dex to induce apoptosis, and FACS sorted based on the gating for two subpopulations: R1 – SYTOhigh/PI− (deemed viable), and R2 – SYTOlow/PI− (deemed early apoptotic) (Fig. 4A). Sorted cells from each gate were seeded in fresh medium, and analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated times. As inferred from bivariate SYTO 16/PI histograms, a fraction of cells from R1 subpopulation underwent apoptosis after withdrawal of cytotoxic drug (Fig. 4A, note the accumulation of SYTOdim/PI− early apoptotic and SYTOdim/PI+ secondary necrotic cells). Despite this, a large number of cells (approx. 48%) remained viable, even after a prolonged cell culture (Figs. 4B, C). In contrast, nearly all cells from R2 population became necrotic, as evidenced by PI exclusion assay (Fig. 4A). Cells sorted from SYTO16high/PI− gate in control samples exhibited neither significant reduction of SYTO16 fluorescence nor PI uptake, indicating low impact of cell sorting and SYTO staining on cell viability (not shown). Interestingly, when SYTO 16 was applied in a dynamic staining protocol, the characteristic loss of fluorescence to “dim” values (indicative of early apoptosis) was more pronounced as compared to the end-point assay. Such improved signal discrimination reduces the ambiguity during data analysis.

Fig. 4.

– Live cell sorting with SYTO 16 probe: (A) Human lymphoma cells were loaded with SYTO 16 (250 nM), treated for 24 h with dexamethasone (Dex; 1 µM) to induce apoptosis and electrostatically sorted based on the following gating strategy: R1 – SYTOhigh/PI− (green; deemed viable), and R2 – SYTOlow/PI− (blue; deemed early apoptotic). Sorted cells from each gate were seeded in a fresh medium, and analyzed by flow cytometry after 24 h of culture (24 h POSTSORT). Note that SYTO-pre-loading allowed to conveniently track phenotype of cells from R1 subpopulation over time. Dynamic labeling reveled that R1 population underwent apoptosis even after withdrawal of cytotoxic drug (accumulation of SYTOdim/PI− early apoptotic and SYTOdim/PI+ secondary necrotic cells); (B) Kinetic viability of B-cell lymphoma cells following sorting procedure described in A). Note that a large number of cells (approx. 48% at 72 h) remained viable after withdrawal of cytotoxic drug. The results represent mean of at least three independent experiments; (C) DNA content analysis on selected subpopulations described in A) and B). Cells were collected at indicated steps and fixed in 70% EtOH for 2 h. Cell cycle analysis was performed using standard PI staining protocol. Note: 1) profound disturbance in cell cycle distribution (G1 cell cycle arrest) in R1 (SYTOhigh/PI−; deemed viable) subpopulation; 2) release of G1-arrest with concomitant increase of sub-G1 fraction (deemed apoptotic) after withdrawal of cytotoxic drug. The results represent mean of at least two independent experiments; SD values were lower than±7 for each phase of DNA content. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

We also determined the applicability of SYTO probes for cell tagging in dynamic cellular multiplexing. A significant problem in cell tagging is not only the leakage into the surrounding media, but also dye transfer into unlabeled cells. This is a major problem for e.g. membrane dyes such as short-chain PKH2 that show a considerable transfer over long-term incubation. To assess cell-to-cell transfer of SYTO probes U937 and HL60 cells were individually encoded using SYTO 16 and SYTO62 dyes, giving three uniquely-labeled and a negative control, unlabeled cell population (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Cells were extensively washed with an excess of PBS and RPMI medium, combined, and analyzed by flow cytometry 0–24 h post co-culture. Four distinctly encoded subpopulations could be recognized and live-sorted for up to 30 min. Substantial leakage of cyanine probes and their secondary uptake by adjacent cells was, however, clearly visible after 24 h of incubation (Supplementary Fig. S3B, right panel). This was characterized by a disappearance of all single labeled and unlabeled populations and strong manifestation of a uniform, double-positive population of U937 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3B). To confirm secondary uptake of SYTOs by unlabeled cells an imaging experiment was performed where U937 cells, pre-labeled with SYTO 16 or SYTO 62, were seeded onto the monolayer of unlabeled osteosarcoma U2OS cells. Fluorescent imaging confirmed the leakage of SYTO16 from pre-tagged U937 cells to a layer of adherent U2OS cells already after 4 h of co-culture (Supplementary Fig. S3C). Similar results were obtained for other SYTO green, orange and red fluorescent probes (data not shown).

Adaptation of SYTO 16 assay for automated Lab-on-a-Chip cytometry

Microfluidic devices are considered as an emerging technology in the field of cell biology and HTS screening [1,11,12]. However, applications of cell-based assays still falls behind microengineering achievements [11,13]. Here, we modified functional SYTO-based assays for the use on microfabricated analytical systems. Under continuous epifluorescent illumination with mercury arc and laser sources SYTO molecules photo-bleach within 10–20 s (Supplementary Movie 1, Supplementary Fig. S4), and thus seem particularly applicable to flow cytometric studies, where repeated sample illumination is avoided. We used the first commercially available microcytometry system, based on Caliper LabChip® technology (Supplementary Fig. S5), which provides very low cell consumption, and complete automation that alleviates laser aligning and operator engagement [14,15]. Microcytometers are often characterized by much lower detection sensitivities than conventional analyzers, particularly for FITC fluorescence (> 2,000,000 MESF of FITC, as opposed to < 500 MESF, respectively) [15]. This can prohibit clear discrimination of dim fluorescent events, such as early apoptotic cells in SYTO-based assays. However, since sensitivities of the channels of Agilent Bioanalyzer and traditional cytometers (5,000 MESF of Cy5) are not much different we adapted SYTO 16 and SYTOX Red (marker of cell membrane permeabilization) probes for automated two-color detection of apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S5) [7,14].

An imperative was to attest that the frequency of cells detected in a gate of interest differs by not more than 10% compared to the reference instrument. Optimization of supravital staining conditions in U937 and HL60 cells revealed that up to 20 fold (from 100 nM to 2 µM) increase in SYTO 16 concentration is needed to permit sufficient discrimination of SYTOhigh subpopulation from background noise by microfluidic cytometry (data not shown). Although our data showed that SYTO 16 was not cytotoxic at doses up to 10 µM, such profound protocol modification can disturb assay performance. To induce caspase-dependent cell death, U937 cells were cultured in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX; 0–10 µg/ml), staurosporine (STS; 1 µM) or camptothecin (CAM; 1 µM) for up to 24 h, followed by an immediate SYTO 16/SYTOX Red staining. Each sample was then divided, separately processed and analyzed using either FACS Calibur flow cytometer (SYTO 16 100 nM; SYTOX Red 10 nM) or Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (SYTO 16 2 µM; SYTOX Red 10 nM). As inferred from the bivariate SYTO 16/ SYTOX dot plots, both platforms allowed for a clear discrimination between live (SYTOhigh/SYTOX−), apoptotic (SYTOdim/SYTOX−) and late apoptotic/necrotic (SYTOlow/SYTOX+) subpopulations (Fig. 5A). In control samples equivalent values for live (84±4% cytometer vs. 81±8% chip), apoptotic (4±2% cytometer vs. 5±7% chip) and late apoptotic/necrotic cells (10±4% cytometer vs. 14±9% chip) were seen. Similarly, in CHX-treated U937 cells live (42±4% cytometer vs. 40±8% chip), apoptotic (27±4% cytometer vs. 34±7% chip) and late apoptotic/necrotic cells (31±4% cytometer vs. 26±9% chip) yielded comparable results (Fig. 5A). The number of viable, apoptotic and necrotic/late apoptotic cells after analysis on both platforms correlated well (R2≥0.85; p < 0.05 for Pearson and Lee linear correlation test) (Fig. 5B). Although chip to chip variation greatly exceeded variations observed using conventional flow cytometer, the excellent correlation between the two such technologically dissimilar platforms provides further support for development of automated microfluidic cytometers [1,14,16]. Prospectively, microfluidic systems with integrated on-chip reagent dispensing, mixing, cell culture, cytometric analysis and sorting modules would provide economical solutions with a superior degree of automation [11,13,15].

Fig. 5.

On-chip detection of apoptosis using SYTO 16 and SYTOX Red probes: (A) U937 cells were cultured in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX) for 24 h followed by an immediate SYTO 16/SYTOX Red staining. Parallel samples were separately analyzed using either conventional flow cytometer (BD FACS Calibur, upper panels) or microfluidic chip-based cytometer (Agilent CellLab Chip, lower panels). Data from chip-based system was converted to FCS 2.0 standard and analyzed using bivariate distribution of SYTO 16 (x-axis) vs. SYTOX Red (y-axis). Note excellent correlation between results from these two technologically dissimilar platforms; (B) Sensitivity of microfluidic cytometry. Cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 0–100 µg/ml), staurosporine (STS; 1 µM). camptothecin (CAM; 1–10 µM) for 1–48 h. After stimulation parallel samples were collected, stained with SYTO 16/SYTOX Red and analyzed separately on a conventional flow cytometer (FACSCalibur) or on-chip microcytometer (Agilent CellLab Chip). Note comparable sensitivity for both analytical platforms (R2≥0.85; p < 0.05 for Pearson and Lee linear correlation test).

Conclusions

Understanding the mechanistic drug action can be greatly enhanced by multivariate kinetic analysis of cell death, which is however limited by inherent probe toxicity and phototoxicity [1,2]. Here we show that cyanine SYTO dyes represent a promising class of probes that do not adversely affect normal cellular physiology. When pre-loaded or continuously present in medium, SYTO 16 does not interfere with cell viability, and its intracellular retention permits straightforward and kinetic analysis of investigational drug/compound cytotoxicity. Reduction of sample processing achieved with these protocols is important for preservation of fragile apoptotic cells. SYTO 16-based live-cell sorting presented here is a novel approach to supravitally track progression of apoptotic cascade in response to investigational anti-cancer agents. Our data indicate also that bioassays detecting subtle changes in fluorescence intensity can be readily adapted for novel microfluidic platforms with minimal protocol modifications.

Such devices promise greatly reduced equipment cost, important for personalized diagnostics (bench-to-bed approach), and can increase throughput of compound library screenings by implementing parallel sample processing [15,17]. Most importantly, as only low cell numbers and reagent volumes are required be microfluidic analyzers, single-cell HTA of rare subpopulations will finally appear within reach, especially for rare, patient derived cell samples [18,19]. We suggest that broader adoption of robotic systems in drug discovery will benefit from development of validated bioassays, such as SYTO-based assays described in this work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NCI CA RO128 704 (ZD); BBSRC, EPSRC and Scottish Funding Council, funded under RASOR (DW, SF and JMC); JS received the L'Oreal-UNESCO “For Women In Science” Award.

Footnotes

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Darzynkiewicz Z. SYTO probes in cytometry of tumor cell death. Cytometry A. 2008;73(6):496–507. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wlodkowic D, Darzynkiewicz Z. Please do not disturb: destruction of chromatin structure by supravital nucleic acid probes revealed by a novel assay of DNA–histone interaction. Cytometry A. 2008;73A(10):877–879. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin RM, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. DNA labeling in living cells. Cytometry A. 2005;67A:45–52. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Pelkonen J. Towards an understanding of apoptosis detection by SYTO dyes. Cytometry A. 2007;71(2):61–72. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wlodkowic D, Skommer J, Hillier Z. Darzynkiewicz, Multiparameter detection of apoptosis using red-excitable SYTO probes. Cytometry A. 2008;73(6):563–569. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idziorek T, Estaquier J, De Bels F, Ameisen JC. YOPRO-1 permits cytofluorometric analysis of programmed cell death (apoptosis) without interfering with cell viability. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;185(2):249–258. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wlodkowic D, Skommer J. SYTO probes: markers of apoptotic cell demise. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2007;42:7.33.1–7.33.12. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0733s42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparrow RL, Tippett E. Discrimination of live and early apoptotic mononuclear cells by the fluorescent SYTO 16 vital dye. J. Immunol. Methods. 2005;305(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darzynkiewicz Z, Juan G, Li X, Gorczyca W, Murakami T, Traganos F. Cytometry in cell necrobiology: analysis of apoptosis and accidental cell death (necrosis) Cytometry. 1997;27(1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telford WG, Komoriya A, Packard BZ. Multiparametric analysis of apoptosis by flow and image cytometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;263:141–160. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-773-4:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersson H, van den Berg A. Microtechnologies nanotechnologies for single-cell analysis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2004;15(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin J, Ye N, Liu X, Lin B. Microfluidic devices for the analysis of apoptosis. Electrophoresis. 2005;26(19):3780–3788. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svahn HA, van den Berg A. Single cells or large populations. Lab. Chip. 2007;7(5):544–546. doi: 10.1039/b704632b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan SD, Luedke G, Valer M, Buhlmann C, Preckel T. Cytometric analysis of protein expression and apoptosis in human primary cells with a novel microfluidic chip-based system. Cytometry A. 2003;55(2):119–125. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sims CE, Allbritton NL. Analysis of single mammalian cells on-chip. Lab. Chip. 2007;7:423–440. doi: 10.1039/b615235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huh D, Gu W, Kamotani Y, Grotberg JB, Takayama S. Microfluidics for flow cytometric analysis of cells and particles. Physiol. Meas. 2005;26(3):R73–R98. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/3/R02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitesides GM. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature. 2006;442:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature05058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Ali J, Sorger PK, Jensen KF. Cells on chips. Nature. 2006;442:403–411. doi: 10.1038/nature05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manz A, Dittrich PS. Lab-on-a-chip: microfluidics in drug discovery. Nat. Drug Discov. 2006;5:210–218. doi: 10.1038/nrd1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.