Abstract

Purpose

These are the clinical experiences of Korean incidental prostate cancer patients detected by transurethral resection of the prostate according to initial treatment: active surveillance (AS), radical prostatectomy (RP) and hormone therapy (HT).

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 156 incidental prostate cancer patients between 2001 and 2012. The clinicopathologic outcomes were reviewed and follow-up results were obtained.

Results

Among 156 patients, 97 (62.2%) had T1a and 59 (37.8%) had T1b. Forty-six (29.5%) received AS, 67 (42.9%) underwent RP, 34 (21.8%) received HT, 4 (2.6%) received radiotherapy, and 5 (3.2%) chose watchful waiting. Of 46 patients on AS, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression occurred in 12 (26.1%) patients. Among them, 3 patients refused treatment despite PSA progression. Five patients, who underwent RP as an intervention, all had organ-confined Gleason score ≤6 disease. In 67 patients who underwent RP, 50 (74.6%) patients had insignificant prostate cancer and 8 (11.9%) patients showed unfavorable features. During follow-up, biochemical recurrence occurred in 2 patients. Among 34 patients who received HT, 3 (8.8%) patients had PSA progression. Among 156 patients, 6 patients died due to other causes during follow-up. There were no patients who died due to prostate cancer.

Conclusion

The clinical outcomes of incidental prostate cancer were satisfactory regardless of the initial treatment. However, according to recent researches and guidelines, immediate definite therapy should be avoided without a careful assessment. We also believe that improved clinical staging is needed for these patients.

Keywords: Incidental prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy, active surveillance

INTRODUCTION

Recently, incidental prostate cancer was diagnosed in less than 5% of patients who undergo benign prostatic hyperplasia-related surgery.1-3 The sub-classification for incidental prostate cancer was established in the 4th TNM staging system in 1992. This classification was the result of several studies that found that patients with incidental prostate cancer had different oncological outcomes according to the percentage of cancer in the resected prostate after transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP); this sub-classification is still applied in the present day.4,5 However, recent study reported that classification according to a volume threshold of 5% tumor involvement is not an independent prognostic factor for prostate cancer prognosis.6 Another study reported that no residual tumor is present after radical prostatectomy (RP) in incidental prostate cancer patients regardless of the incidental prostate cancer stage.7 Thus, there is still a controversy regarding which treatment is appropriate in cases of incidental detection of prostate cancer.

In our institute, several incidental prostate cancer patients were followed up, and their different clinical results were analyzed according to the initial treatment modalities. Here, we present the clinical experiences of these patients and discuss which treatment was the most appropriate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 156 patients who had prostate cancer, detected incidentally during TURP, between 2001 and 2012. We excluded patients with positive prostate biopsy in simultaneous TURP and prostate biopsy, even if there were prostate cancer chips in the TURP specimens. Clinical stage was determined according to a volume threshold of 5% tumor involvement after TURP. We collected clinical and pathological parameters, including age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) before/after TURP, prostate volume, resected prostate volume after TURP, Gleason score at TURP, clinical stage, and the initial treatment type. We also collected overall survival data.

We stratified the patients into three groups according to their main initial treatment: active surveillance (AS), RP, or hormone therapy (HT). For the AS group, we collected information about the period of AS, PSA progression status, intervention status during follow-up, the reason for intervention on AS, and the type of intervention. We defined PSA progression as a doubling of the serum total PSA level in comparison with the post-TURP PSA. In the case of the RP group, we collected information about the pathologic stage, postoperative Gleason score, extracapsular extension (ECE), seminal vesicle invasion (SVI), perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, tumor volume, surgical margin status, the proportion of insignificant prostate cancer, the proportion of unfavorable disease, and biochemical recurrence (BCR) status. We defined insignificant prostate cancer as organ-confined Gleason ≤6 disease with a tumor volume of <0.5 cm3, and unfavorable disease as prostate cancer with ECE and/or SVI and/or a postoperative Gleason score of ≥8. BCR was defined as a sustained increase in serum total PSA level of ≥0.2 ng/mL. In the HT group, we collected information regarding PSA progression according to the type of hormone therapy. In this group, we defined PSA progression as a sustained increase in serum total PSA levels of ≥0.4 ng/mL.

We compared the clinical and pathological characteristics of each group using the chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

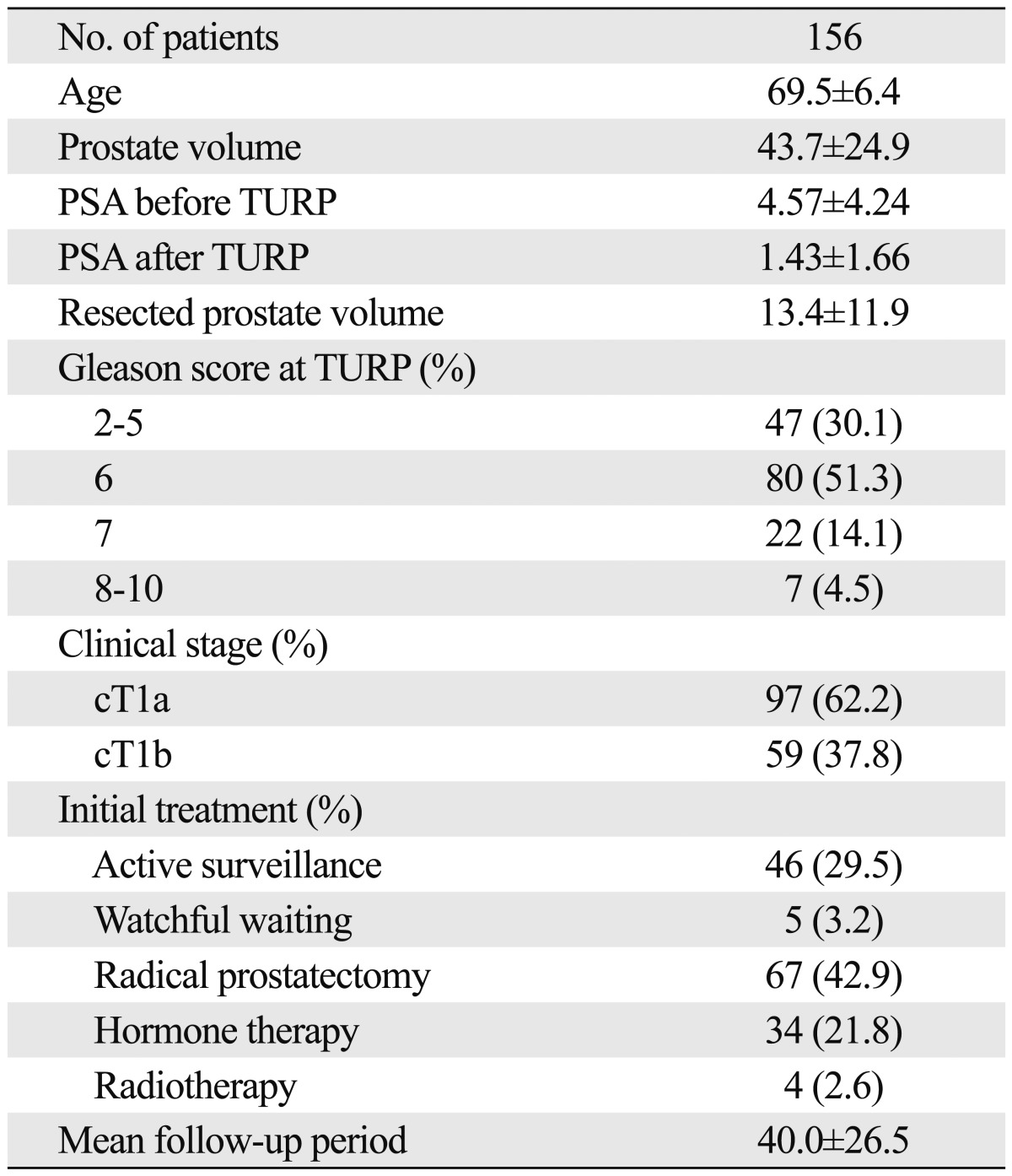

We identified 156 incidental prostate cancer patients at our institute. The baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. In total, 97 (62.2%) patients were stage T1a and 59 (37.8%) were T1b. The average PSA before TURP was 4.57±4.24 ng/mL and 1.43±1.66 ng/mL after TURP. Among them, 46 (29.5%) patients received AS, 67 (42.9%) patients underwent RP, 34 (21.8%) received HT, 4 (2.6%) received radiotherapy (RT), and 5 (3.2%) chose watchful waiting (WW). Among those who chose WW, 2 patients were of advanced age and 3 patients had other pathologically proven malignancies. Four patients chose RT because they refused RP. Of these 156 incidental prostate cancer patients, 6 patients died of other causes during follow-up and there were no patients who died due to prostate cancer.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate.

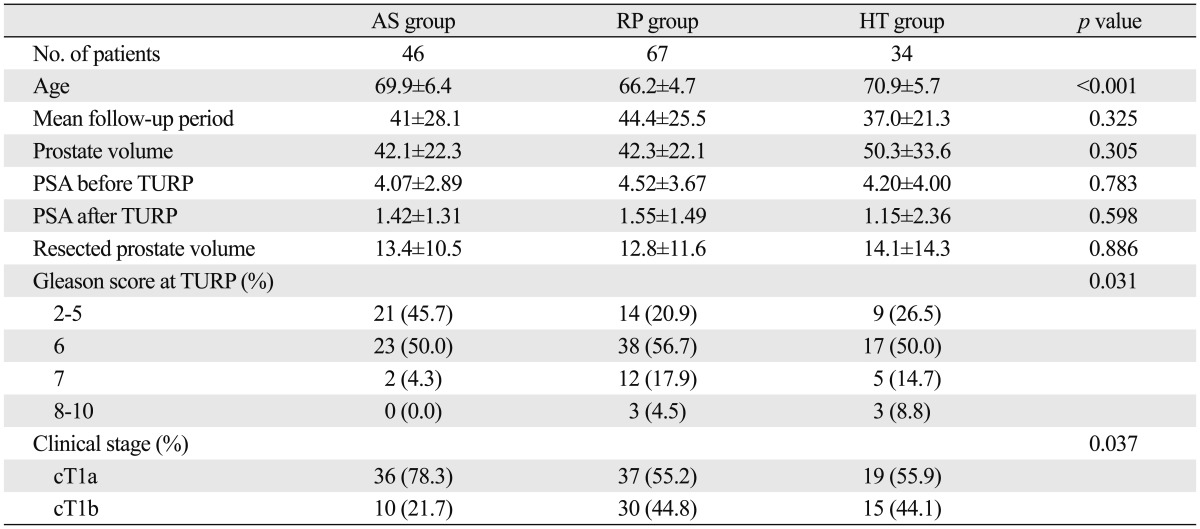

We compared clinicopathologic characteristics according to initial treatment (Table 2). There were no statistical differences between initial treatment and follow-up period, PSA before TURP, prostate volume, or resected prostate volume after TURP. However, the mean age of the RP group was younger than that of other groups (p<0.001). Gleason score at TURP and clinical stage were statistically different between the AS group and other groups (p=0.031 and p=0.037, respectively).

Table 2.

Comparison of the Clinicopathological Outcomes of Patients with Incidental Prostate Cancer According to Treatment

AS, active surveillance; RP, radical prostatectomy; HT, hormone therapy; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostate.

Active surveillance group

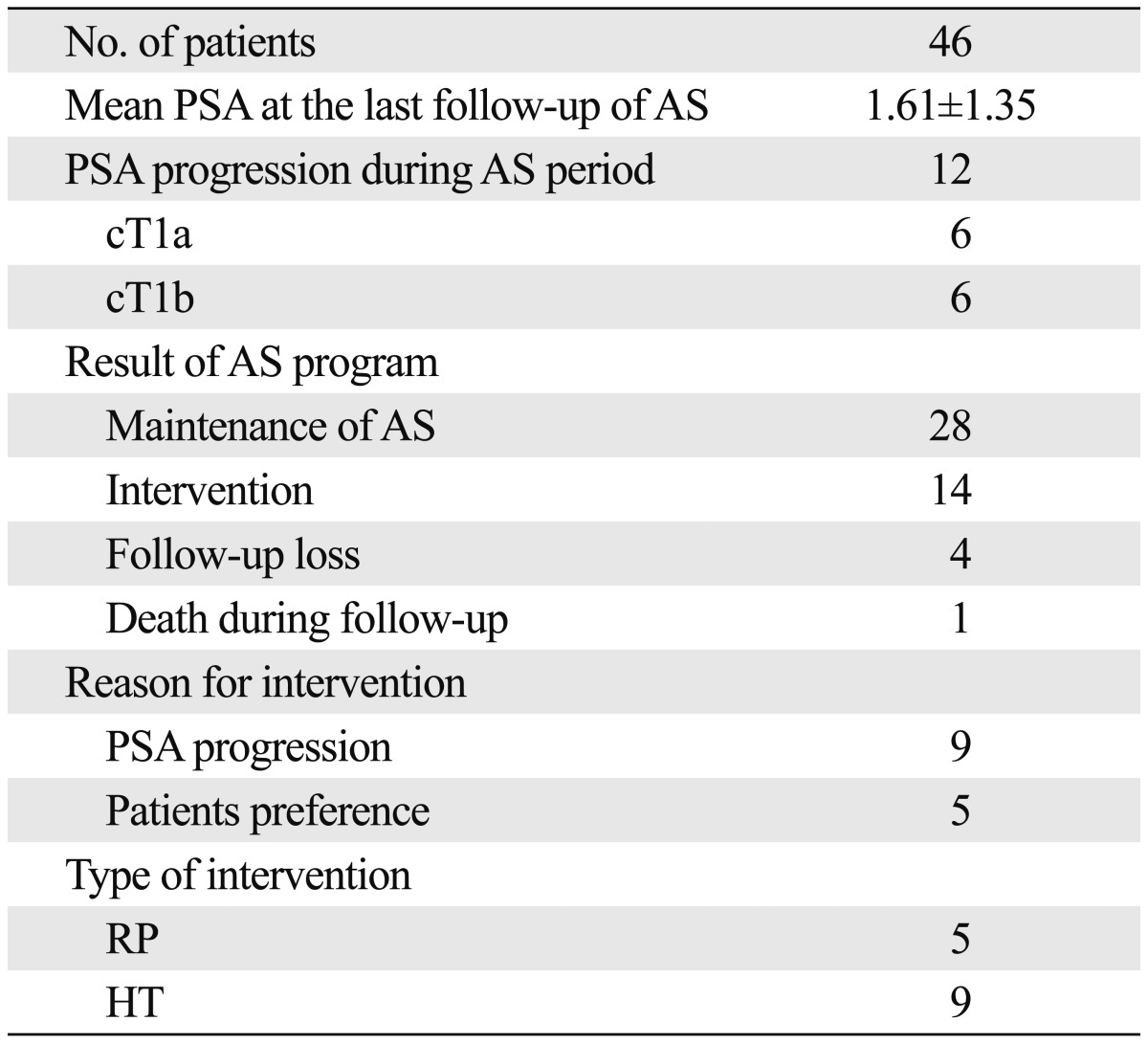

The clinical results of the patients who received AS are shown in Table 3. In the AS group, 27 (65.2%) patients continued in the AS program, 14 (23.9%) received interventions, and 1 patients died from other causes. Twelve (26.1%) patients exhibited PSA progression during AS. Among these, 3 patients refused to receive any treatment despite PSA progression and 9 patients received treatment for PSA progression. Finally, out of 14 patients who received intervention, 5 patients were treated because of patient preference, even though there was no evidence of disease progression. Among the patients who received intervention, 5 patients underwent RP and 9 patients received HT. Among the patients who chose RP for intervention, 2 patients had insignificant prostate cancer and other 3 patients had organ-confined disease with a Gleason score of ≤6.

Table 3.

Clinical Results of Patients with Incidental Prostate Cancer Who Received Active Surveillance

AS, active surveillance; RP, radical prostatectomy; HT, hormone therapy; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Radical prostatectomy group

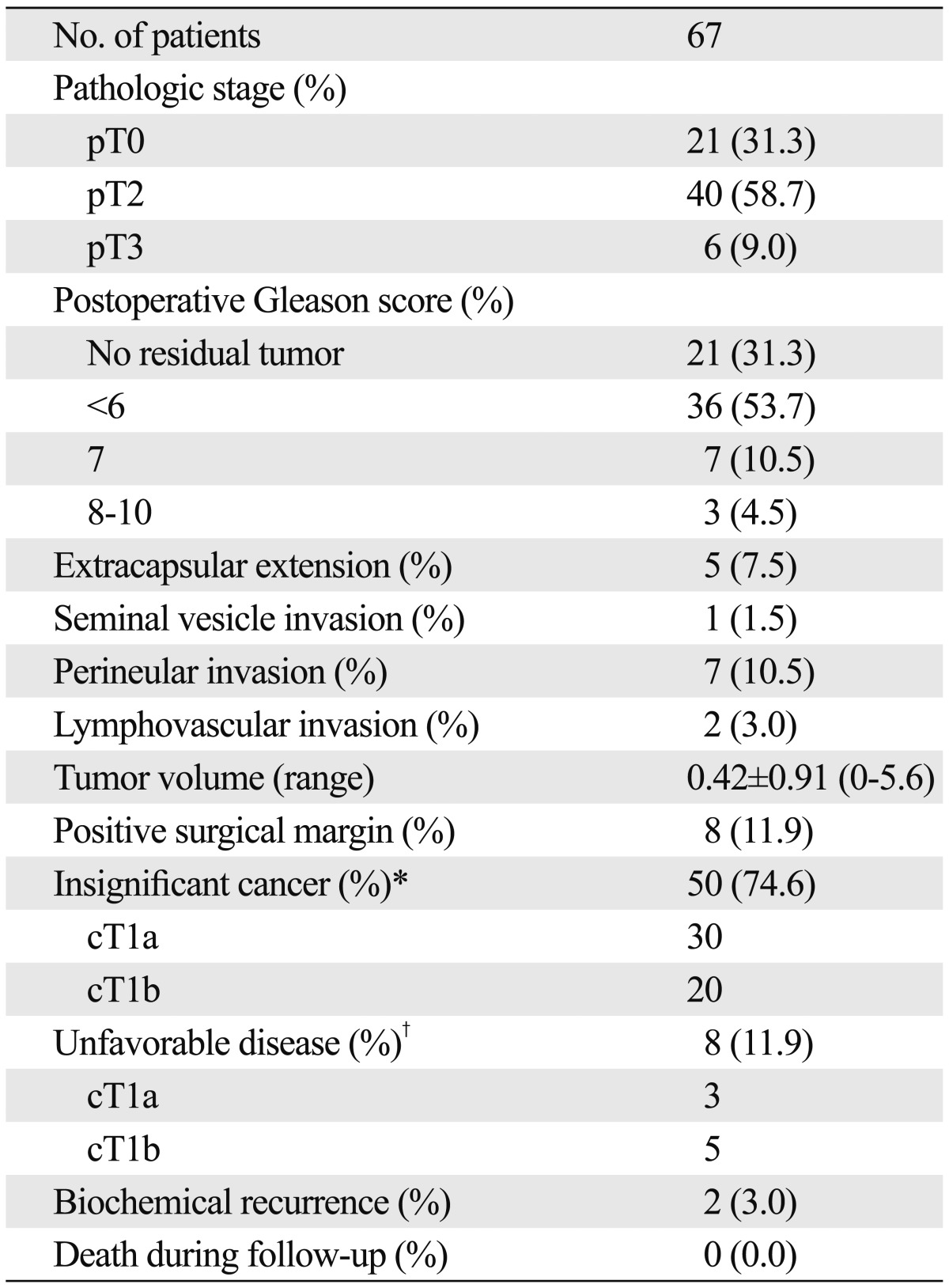

The pathologic outcomes after RP are listed in Table 4. In total, 21 of 67 (31.3%) patients had no residual prostate cancer. The average tumor volume was 0.42±0.91 (range: 0-5.6). Fifty (74.6%) patients had insignificant prostate cancer. Among these, 30 patients were clinical stage T1a and 20 patients were clinical stage T1b. Eight (11.9%) patients had unfavorable features. Among these, 3 patients were clinical stage T1a and 5 patients were clinical stage T1b. During follow-up, biochemical recurrence occurred in 2 patients.

Table 4.

Pathologic Outcomes of Patients Who Underwent Radical Prostatectomy

*Tumor volume <0.5 cm3, organ-confined Gleason ≤6 disease.

†Extracapsular extension and/or seminal vesicle invasion and/or postoperative Gleason score ≥8.

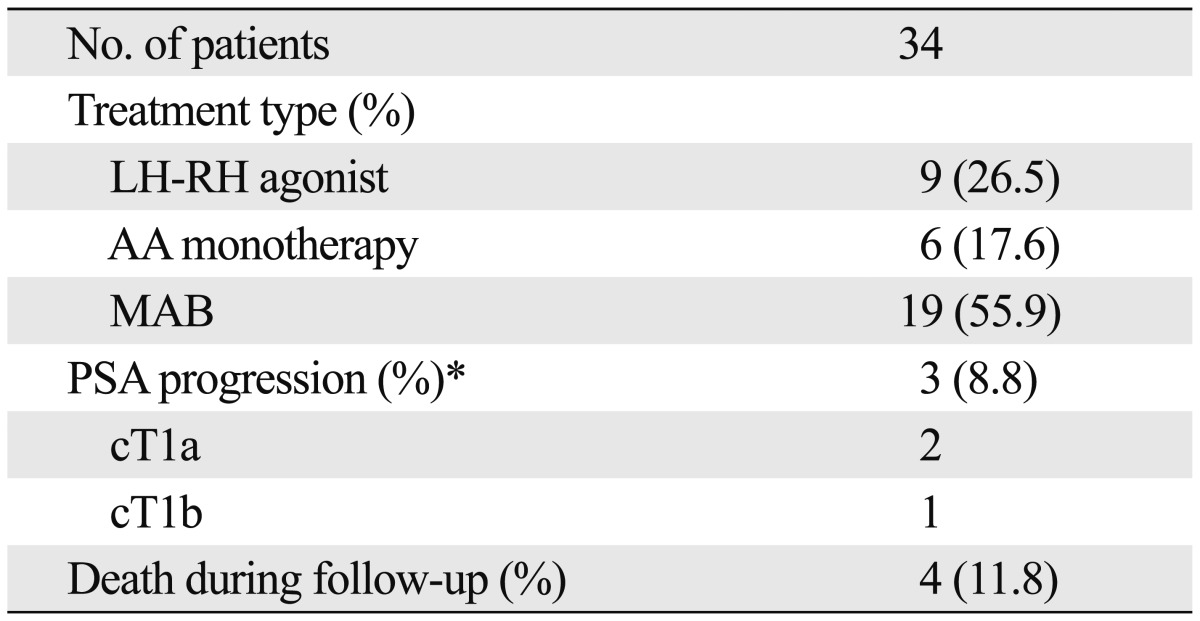

Hormone therapy group

Among the 34 patients who received HT, 9 (26.5%) patients received luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists, 6 (17.6%) patients received anti-androgen (AA) monotherapy, and 19 (55.9%) patients received maximal androgen blockage (MAB). Three patients demonstrated PSA progression over 0.4 ng/mL. Among them, 1 patient received MAB and 2 patients received AA monotherapy. Among the HT group, 4 patients died from non-prostate cancer causes during follow-up (Table 5).

Table 5.

Clinical Outcomes of Patients Who Received Hormone Therapy

LH-RH, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; AA, anti-androgen; MAB, maximal androgen blockage; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

*PSA progression defined as an increase of PSA level ≥0.4 ng/mL.

Overall survival of incidental prostate cancer patients

Among 156 patients, a total of 6 (3.8%) patients died during follow-up. One patient on AS died due to cerebral hemorrhage, while another on WW died due to pancreatic malignancy. Among the remaining 4 patients on HT, 2 patients died due to aging, 1 patient due to liver malignancy and another due to congestive heart failure. During follow-up, no patients died due to prostate cancer.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have shown that the rate of incidental prostate cancer discovery has decreased in the PSA era. Jones, et al.8 reported that the incidence of incidental prostate cancer has significantly decreased in comparison to the rate from the pre-PSA era. They also reported that the most significant drop was in cases of clinical stage T1b. Andrèn, et al.9 reported similar results in a large Swedish national study cohort. Notably, the Swedish study also reported differences in prostate-cancer-specific mortality. They reported that a significant proportion of men diagnosed with incidental prostate cancer during the last three decades died from their disease; however, prostate-cancer-specific mortality has decreased over time in the PSA era.

In fact, PSA screening has led to an increase in the diagnosis of prostate cancer by prostate biopsy. Consequently, a large proportion of prostate cancers are being diagnosed in early stages and at younger ages, before patients exhibit lower urinary tract symptoms. In the pre-PSA era, there was a greater possibility that incidental prostate cancer would be locally advanced prostate cancer rather than 'true' incidental prostate cancer, since early detection of prostate cancer by PSA screening was not available. In addition, considering the PSA prostate biopsy strategy, simultaneous TURP and prostate biopsy are frequently performed in patients who have a higher PSA level than 4.0 ng/mL. Diagnosis of incidental prostate cancer is not made if simultaneous TURP and prostate biopsy give a positive result, even if prostate cancer is seen in TURP chips. Thus, in the PSA era, incidental prostate cancer can be diagnosed at lower PSA levels. In our study cohort, 91 patients who were tested for PSA before TURP had levels less than 4.0 ng/mL, and the remaining 65 patients had PSA levels higher than 4.0 ng/mL. Of these 65 patients, 12 underwent core prostate biopsy and were found to have peripheral prostate cancer on biopsy. In other words, these patients were more likely to be diagnosed as cancer-free by prostate biopsy if they did not undergo TURP.

Another controversy surrounding incidental prostate cancer concerns the choice of clinical staging used to plan prostate cancer treatment. Sub-classification of incidental prostate cancer was based on a study performed 20 years ago. Although the characteristics of clinical stage T1a/T1b patients have gradually changed over the past few decades, sub-classifications are still applied without modification. The classical approach is to follow T1a patients with an active surveillance program and to treat T1b patients. European Association of Urology guidelines recommend active surveillance for stage T1a and radical prostatectomy for stage T1b patients with a life expectancy of more than 10 years.10

Descazeaud, et al.11 reported that 30 of 144 (21%) stage T1a patients experienced cancer progression during the AS period. They concluded that AS was appropriate for these patients in the PSA era. In the present study, 12 patients in the AS group showed PSA progression. Among these patients, 6 of 36 (16.7%) stage T1a patients and 6 of 10 (60%) stage T1b patients demonstrated PSA progression. Comparing the proportion of those with PSA progression according to clinical stage, clinical stage T1b patients seemed to have a greater chance of PSA progression in comparison with stage T1a patients. However, incidental prostate cancer PSA progression is questionable because no consensus definition of progression has been developed. In addition, it is unclear whether PSA progression during AS indicates disease progression in incidental prostate cancer patients. It should not be overlooked that, 5 patients in the present study, who received RP after PSA progression had organ-confined Gleason 6 disease regardless of clinical stage.

Several studies have reported that stage T1b cancer has a poorer prognosis than stage T1a.12-15 However, Magheli, et al.6 reported that a sub-classification of incidental prostate cancer was not an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence after adjustment for PSA, Gleason score, or year of surgery in patients who underwent RP. Capitanio, et al.7,16 concluded that PSA value before and after surgery and Gleason score at surgery were the only significant predictors of residual cancer after RP. Other studies have shown that the current T staging system cannot be used for accurate staging of the remnant prostate after TURP, and that clinical stage T1a/T1b based on the percentage of the resected tumor volume does not represent the status of disease progression.17 In the present study, we found no significant evidence on RP specimens to prove that clinical stage T1b patients had a worse prognosis than T1a patients, because our study cohort had a low BCR rate (3.0%). This result was similar in the HT group.

In the present study, the rate of insignificant prostate cancer, including the absence of residual prostate cancer, was higher than that in other published data.7,18 We are at a loss to explain why our study cohort had more insignificant prostate cancer in comparison with other studies. Nevertheless, considering that the proportion of insignificant prostate cancer after RP is unpredictable and that there has been a wide variation shown in different studies regardless of clinical stage, RP is beginning to be an overtreatment for incidental prostate cancer in the PSA era. Accordingly, several authors have proposed steps to reduce such overtreatment. Among them, Capitanio, et al.19 emphasized the importance of communication between urologists and pathologists in incidental prostate cancer management. First, pathologists should exam every TURP chip. Second, cancer extent should be measured by the percentage of chips infiltrated by cancer. They concluded that clinical and pathologic background knowledge should be shared for accurate evaluation and management.

Recently, Capitanio, et al.1,7,16 concluded that the management of incidental prostate cancer should be based on the estimated probability of clinical progression compared to the relative risk of therapy and survival of the patient. They concluded that clinical stage (T1a vs. T1b), Gleason score at diagnosis and PSA values before and after TURP are the most informative variables in clinical decisions. Rajab, et al.20 suggested that the current sub-classification for incidental prostate cancer results in a substantial loss of information, and that the sub-classification of incidental prostate cancer should be changed from the present two subdivisions to four subdivisions in order to improve prognostic evaluation. Based on our own experiences, we agree strongly with this suggestion. We believe that the concept of incidental prostate cancer has changed with the wide use of PSA screening. In the PSA era, incidental prostate cancer patients should be considered to be low-risk prostate cancer patients, and immediate definite therapy should be sublated for these patients. Before and post-TURP, PSA values or systematic prostate biopsy of the remaining prostate tissue should be used for proper decision-making. The use of AS for these patients over RP or HT as an initial treatment may reduce the occurrence of complications due to treatment.

The present study had several limitations. First, the follow-up period was short in comparison with other studies. Second, this study was simply a review of clinical outcomes according to initial treatments. Only a few patients who had poorly differentiated incidental prostate cancer were included in the study cohort. However, our results are comparable with other recent findings, and this article is the first report of clinical outcomes according to initial treatments using a Korean cohort. Even though it was impossible to compare the clinical outcomes according to Gleason score at TURP, the decrease of patients with poorly differentiated incidental prostate cancer was similar to what has been reported by other tertiary hospitals. Despite these limitations, we believe that our clinical experiences could have implications for urologists who are involved in the treatment of incidental prostate cancer patients.

In conclusion, the clinical outcomes of incidental prostate cancer were satisfactory regardless of the initial treatment type. However, according to recent research and guidelines, immediate definite therapy should be avoided without a careful assessment. We also believe that improved clinical staging is needed for these patients.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Capitanio U. Contemporary management of patients with T1a and T1b prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:252–256. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e328344e4ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zigeuner RE, Lipsky K, Riedler I, Auprich M, Schips L, Salfellner M, et al. Did the rate of incidental prostate cancer change in the era of PSA testing? A retrospective study of 1127 patients. Urology. 2003;62:451–455. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng L, Bergstralh EJ, Scherer BG, Neumann RM, Blute ML, Zincke H, et al. Predictors of cancer progression in T1a prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:1300–1304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990315)85:6<1300::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jewett HJ. The present status of radical prostatectomy for stages A and B prostatic cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 1975;2:105–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantrell BB, DeKlerk DP, Eggleston JC, Boitnott JK, Walsh PC. Pathological factors that influence prognosis in stage A prostatic cancer: the influence of extent versus grade. J Urol. 1981;125:516–520. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magheli A, Rais-Bahrami S, Carter HB, Peck HJ, Epstein JI, Gonzalgo ML. Subclassification of clinical stage T1 prostate cancer: impact on biochemical recurrence following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2007;178(4 Pt 1):1277–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capitanio U, Briganti A, Suardi N, Gallina A, Salonia A, Freschi M, et al. When should we expect no residual tumor (pT0) once we submit incidental T1a-b prostate cancers to radical prostatectomy? Int J Urol. 2011;18:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones JS, Follis HW, Johnson JR. Probability of finding T1a and T1b (incidental) prostate cancer during TURP has decreased in the PSA era. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:57–60. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrèn O, Garmo H, Mucci L, Andersson SO, Johansson JE, Fall K. Incidence and mortality of incidental prostate cancer: a Swedish register-based study. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:170–173. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heidenreich A, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol. 2011;59:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Descazeaud A, Peyromaure M, Salin A, Amsellem-Ouazana D, Flam T, Viellefond A, et al. Predictive factors for progression in patients with clinical stage T1a prostate cancer in the PSA era. Eur Urol. 2008;53:355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein JI, Paull G, Eggleston JC, Walsh PC. Prognosis of untreated stage A1 prostatic carcinoma: a study of 94 cases with extended followup. J Urol. 1986;136:837–839. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulson DF, Moul JW, Walther PJ. Radical prostatectomy for clinical stage T1-2N0M0 prostatic adenocarcinoma: long-term results. J Urol. 1990;144:1180–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masue N, Deguchi T, Nakano M, Ehara H, Uno H, Takahashi Y. Retrospective study of 101 cases with incidental prostate cancer stages T1a and T1b. Int J Urol. 2005;12:1045–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefi M, Hellara W, Touffahi M, Fredj N, Adnene M, Saidi R, et al. [Prostate cancer: comparative study of stage T1a and stage T1b] Prog Urol. 2007;17:1343–1346. doi: 10.1016/s1166-7087(07)78574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capitanio U, Scattoni V, Freschi M, Briganti A, Salonia A, Gallina A, et al. Radical prostatectomy for incidental (stage T1a-T1b) prostate cancer: analysis of predictors for residual disease and biochemical recurrence. Eur Urol. 2008;54:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adolfsson J. The management of category T1a-T1b (incidental) prostate cancer: can we predict who needs treatment? Eur Urol. 2008;54:16–18. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melchior S, Hadaschik B, Thüroff S, Thomas C, Gillitzer R, Thüroff J. Outcome of radical prostatectomy for incidental carcinoma of the prostate. BJU Int. 2009;103:1478–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capitanio U, Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Scarpelli M, Freschi M, Montorsi F, et al. The importance of interaction between urologists and pathologists in incidental prostate cancer management. Eur Urol. 2011;60:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajab R, Fisher G, Kattan MW, Foster CS, Møller H, Oliver T, et al. An improved prognostic model for stage T1a and T1b prostate cancer by assessments of cancer extent. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:58–63. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]