Abstract

Background: Osteopathic practitioners utilize manual therapies called lymphatic pump techniques (LPT) to treat edema and infectious diseases. While previous studies examined the effect of a single LPT treatment on the lymphatic system, the effect of repeated applications of LPT on lymphatic output and immunity has not been investigated. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to measure the effects of repeated LPT on lymphatic flow, lymph leukocyte numbers, and inflammatory mediator concentrations in thoracic duct lymph (TDL).

Methods and Results: The thoracic ducts of five mongrel dogs were cannulated, and lymph samples were collected during pre-LPT, 4 min of LPT, and 2 hours post-LPT. A second LPT (LPT-2) was applied after a 2 hour rest period. TDL flow was measured, and TDL were analyzed for the concentration of leukocytes and inflammatory mediators. Both LPT treatments significantly increased TDL flow, leukocyte count, total leukocyte flux, and the flux of interleukin-8 (IL-8), keratinocyte-derived chemoattractant (KC), nitrite (NO2−), and superoxide dismutase (SOD). The concentration of IL-6 increased in lymph over time in all experimental groups; therefore, it was not LPT dependent.

Conclusion: Clinically, it can be inferred that LPT at a rate of 1 pump per sec for a total of 4 min can be applied every 2 h, thus providing scientific rationale for the use of LPT to repeatedly enhance the lymphatic and immune system.

Introduction

The lymphatic system is essential for interstitial fluid homeostasis and function of the immune system.1–3 Interstitial fluid homeostasis is maintained by lymphatic absorption of excess interstitial tissue fluid and by transport of this fluid, along with osmotically active proteins, parenchymal cell products, inflammatory mediators, immune cells, proteins, apoptotic cells, antigens, and infectious organisms through the nodes to the circulation.2,4 In addition to transporting immunological factors, the lymphatic system actively participates in immune surveillance and the induction of immune responses, while maintaining self-tolerance. Dysfunction of the lymphatic system leads to edema, impaired trafficking of immune cells, accumulation of inflammatory mediators, tissue hypoxia and injury, inflammation, and a variety of diseases.5–8

Edema, whether due to lymphatic dysfunction or to other causes, is generally treated by procedures designed to increase lymph flow or prevent the accumulation of fluid into tissue. These procedures include movement or elevation of dependent limbs and tissue compression.9,10 When these procedures are inadequate, pharmacological or surgical interventions may be required.9–11 Osteopathic physicians have developed manual lymphatic pump techniques (LPT) to increase lymph flow.5,12 Considering the important role of the lymphatic system in immune function, LPT is also used to treat infections.5,12

Previously, we demonstrated that a single application of LPT increased lymph flow and leukocyte flux in both rats and dogs, and mobilized inflammatory mediators into lymph circulation.13–19 These findings support the use of LPT to treat edema and to enhance immune function. Importantly, the effects of LPT on the lymphatic system were transient, suggesting this LPT-sensitive lymph reservoir is limited.13–19 The purpose of this study was to determine if a second application of LPT could also enhance lymph flow, the number of leukocytes, and the concentration of inflammatory mediators in thoracic duct lymph. Our results demonstrate that LPT can be repeatedly applied to enhance lymph flow, leukocyte numbers, and the flux of inflammatory mediators. The LPT-sensitive reservoir these techniques draw from is largely restored by 2 h, thus supporting the clinical application of repeated LPT.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). Five adult mongrel dogs, free of clinically evident signs of disease, were used for this study.

Surgical procedures and experimental protocols

Prior to surgery, the dogs were fasted overnight and then anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg, IV). After endotracheal intubation, the dogs were ventilated with room air and supplemented with oxygen to maintain normal arterial blood gases. Arterial blood pressure (AOP) was monitored via a femoral artery pressure monitoring catheter connected to a pressure transducer (Hewlett–Packard Pressure Monitor, 78354A); AOP remained within normal limits throughout the experiment. Blood samples were periodically collected from the femoral artery catheter and assessed for arterial blood gases and pH (GEM Premier 3000 Blood Gas/Electrolyte Analyzer, Model 5700, Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA). The chest was opened by a left lateral thoracotomy in the fourth intercostal space. The thoracic duct was isolated from connective tissue and ligated. Caudal to the ligation, a PE 60 catheter (i.d. 0.76 mm, o.d. 1.22 mm) was inserted into the duct and secured with a ligature. Lymph was drained at atmospheric pressure through a catheter whose outflow tip was positioned 8 cm below heart level to compensate for the hydraulic resistance of the catheter.

Lymphatic pump technique

LPT was performed by a medical student (A.S.) trained in osteopathic lymphatic manipulation. During manipulation, the anesthetized dogs were placed in a right lateral recumbent position. To perform abdominal LPT, the operator contacted the ventral side of the animal's abdomen with the hands placed bilaterally below the costo-diaphragmatic junction. Sufficient pressure was exerted medially and cranially to compress the abdomen until significant resistance was encountered against the diaphragm, and then the pressure was released. Abdominal compressions were administered at a rate of approximately 1 per sec for a total of 4 min.

Leukocyte enumeration and flux

Total leukocytes and a differential leukocyte count in lymph samples were enumerated using the Hemavet 950 (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT). To compute TDL leukocyte flux, leukocyte concentrations were multiplied by the respective lymph flow rates for each condition. Fluxes of specific leukocyte populations, cytokines, chemokines, nitrite, and SOD were computed in a similar manner.

Measurement of inflammatory mediators

A commercially available multiplex assay (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to determine the concentrations of cytokines and chemokines in TDL. Specifically, the cytokine IL-6 and chemokines IL-8 and KC were measured. A range of standards provided with the multiplex assay was used, and the assay was analyzed using the Luminex R 200 System with the xPONENT Software Interface (Millipore). The minimum detectable concentrations for IL-6, IL-8, and KC were 12.1, 20.3, and 1.6 pg/mL, respectively. Cytokine/chemokine fluxes in TDL were computed from the product of respective concentrations and flows, as were fluxes of total leukocytes.

Thoracic lymph concentrations of nitrite (NO2-) and SOD were measured using commercially available kits (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, and Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). The Promega Griess Reagent system measures NO2−, a nonvolatile and stable breakdown product of nitric oxide (NO).20,21 The minimum detectable nitrite concentration for this assay is 2.5 μM. The SOD assay measures all three forms of SOD (cytosolic Cu/Zn-SOD, mitochondrial MnSOD, and extracellular FeSOD) by utilizing a tetrazolium salt for the detection of xanthine oxidase and hypoxanthine-derived superoxide radicals. One unit of SOD is defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to cause 50% dismutation of the superoxide radical. The minimum detectable SOD concentration for this assay is 0.025 U/mL. TDL fluxes of these agents were computed similarly to that of other agents, as described above.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as arithmetic means±standard error (SE). Values from multiple animals at respective time points were averaged, and the mean values are shown in tables or in figures. For evaluation of statistical significance, data were subjected to repeated measures analyses of variance, followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons post hoc tests. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 5.04 and GraphPad InStat version 3.06 for Windows, (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences among mean values with at least p≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct lymph flow

Sample collection points are illustrated in Figure 1. TDL flow values before (pre), during, and after (post) LPT are illustrated in Figure 2. Consistent with our previous reports,14,16,17 LPT increased TDL flow from 0.3±0.1 mL/min (pre-LPT) to an average of 6.0±1.2 mL/min (p<0.001) during the 4 min of LPT 1. After cessation of LPT 1, lymph flow decreased to 0.4±0.1 mL/min (p<0.001). TDL flow did not vary during the 2 h interval (14–124 min) between LPT 1 and LPT 2 (Fig. 2). Similar to LPT 1, LPT 2 significantly (p<0.001) increased TDL flow from 0.3±0.1 mL/min during pre-LPT to an average of 5.5±0.5 mL/min during LPT 2 (Fig. 2). These LPT-induced increases in lymph flow did not differ significantly (p>0.05). Following LPT 2, lymph flow decreased to 0.3±0.1 mL/min (p<0.001). While lymph flow throughout the 4 min periods of LPT 1 and LPT 2 remained significantly elevated compared to their respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values, both treatments caused the greatest increase in lymph flow during the first minute of LPT (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Experimental design. Approximately 60 min after cannulation of the thoracic duct, thoracic duct lymph (TDL) was collected during 4 min of baseline (pre-LPT), at 1 min intervals during 4 min of LPT (LPT 1), for 10 min (post-LPT), 90 min (rest), 4 min (pre-LPT 2), at 1 min intervals during 4 min of LPT (LPT 2), and for 10 min after cessation of LPT (post-LPT). Lymph flow rates were calculated from the volume of lymph collected during these intervals.

FIG. 2.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct lymph flow. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

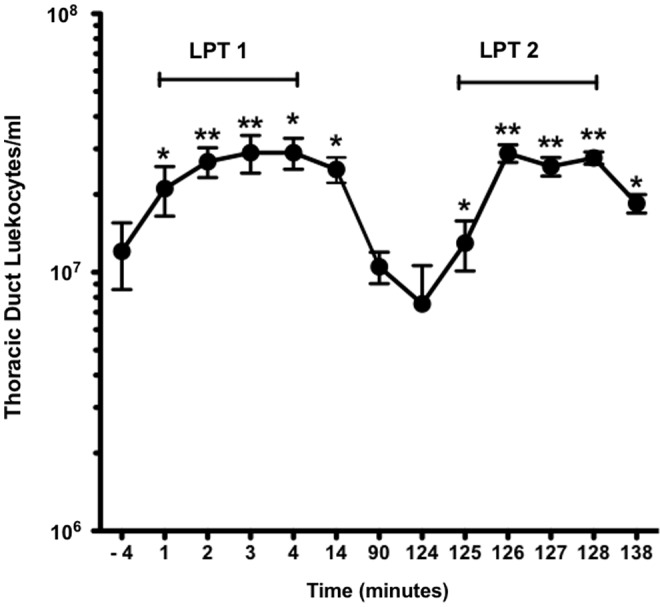

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct leukocytes

The effect of LPT on total leukocyte numbers is reported in Figure 3. Leukocyte counts were significantly elevated at 1 min (p<0.054) and continued to elevate at 2, 3, and 4 min of LPT 1, as well as throughout the period of LPT 2. The average pre-LPT 1 baseline leukocyte count was 12.1±3.5×106 cells/mL, and LPT 1 significantly increased leukocyte numbers to 26.5±3.4×106 cells/mL (p<0.001). Ten min following LPT 1 (14 min), the leukocyte count in TDL remained elevated at 25.0±2.8×106 cells/mL (p<0.001). By 90 min, leukocytes returned to baseline (10.5±1.5×106 cells/mL). LPT 2 significantly increased leukocyte numbers from 7.6±3.1×106 cells/mL during pre-LPT 2 to 25.6±1.4×106 cells/mL (p<0.001). As seen following LPT 1, the leukocyte count remained significantly elevated for 10 min following LPT 2 (P<0.01). There were no significant differences in TDL flow between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

FIG. 3.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct leukocytes. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.01). **Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

To determine if LPT preferentially increased a specific leukocyte population, we measured the percentage and concentration of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes in TDL (Table 1). LPT 1 significantly increased the TDL count of neutrophils (p<0.001) by 251%, monocytes by 116% (p<0.01), and of lymphocytes (p<0.001) by 111% compared to pre-LPT 1. Subsequently, the count decreased post-LPT 1 by 73% for neutrophils (p<0.001), 72% (p<0.01) for monocytes, and 56% for lymphocytes (p<0.001). In a similar fashion, LPT 2 significantly increased TDL count of neutrophils by 402% (p<0.05), monocytes by 181% (p<0.01), and of lymphocytes by 240% (p<0.05) compared to pre-LPT 2. Subsequently, the count decreased post-LPT 2 by 36% (p<0.05) for neutrophils, 29% (p<0.161) for monocytes, and 26% (p<0.05) for lymphocytes. No significant (p>0.05) differences in TDL neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts were detected between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

Table 1.

LPT Increases the Concentration of Leukocytes in Thoracic Duct Lymph

| Pre-LPT 1 | LPT 1 | Post-LPT 1 | Pre-LPT 2 | LPT 2 | Post-LPT 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte count (× 106 cells/ml) | ||||||

| NO |

0.63±0.29 |

2.21±0.47*** |

0.59±0.16 |

0.45±0.26 |

2.26±0.30* |

1.44±0.25 |

| MO |

2.09±0.88 |

4.52±1.10** |

1.25±0.36 |

1.44±0.83 |

4.04±0.92† |

2.86±0.48 |

| LY |

9.31±2.38 |

19.6±2.15*** |

8.64±1.06 |

5.64±1.97 |

19.17±0.59* |

14.1±1.07 |

| Percentage of leukocytes | ||||||

| NO |

4.3±0.9 |

7.9±0.8** |

5.1±0.7 |

4.7±0.7 |

8.6±0.8† |

7.5±0.9 |

| MO |

14.9±2.7 |

16.4±2.3 |

11.2±2.2 |

15.9±2.3 |

15.2±2.5 |

15.3±2.2 |

| LY | 80.8±3.6 | 75.4±3.1 | 83.5±2.7 | 79.0±3.0 | 75.9±3.2 | 76.9±2.6 |

Thoracic duct lymph was collected over ice from five anesthetized dogs and analyzed.

LPT, lymphatic pump technique; LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; NO, neutrophils.

Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.05). **Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.01). ***Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). †Greater than respective Pre-LPT (p<0.01). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

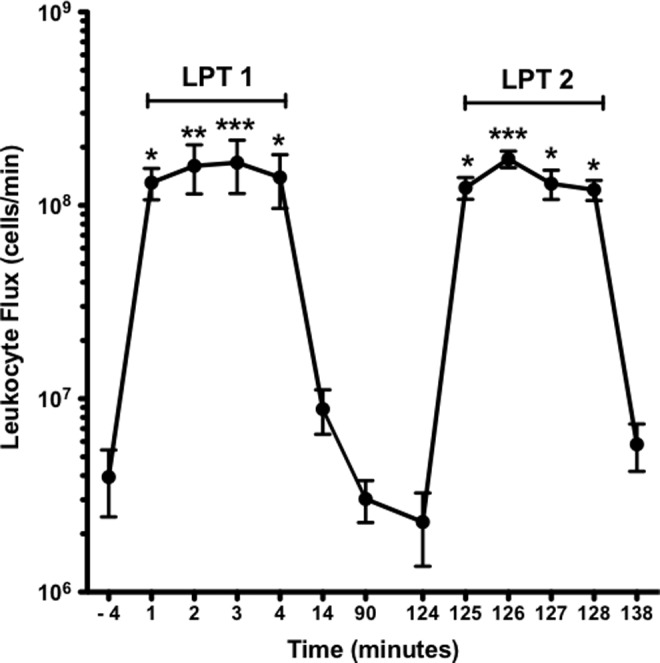

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct leukocyte flux

TDL leukocyte flux values are reported in Figure 4. LPT accelerated TDL leukocyte flux from a mean pre-LPT 1 value of 3.9±1.5×106 cells/min to a peak value of 166±51×106 cells/min at 3 min of LPT 1 (p<0.001). Throughout 4 min of LPT 1, TDL leukocyte flux remained elevated (p<0.001), averaging 149.3±34×106 cells/min. The flux at 14 min averaged 8.8±2.3×106 cells/min (p<0.001) and was 3.0±0.7×106 cells/min at 90 min, suggesting the effect of LPT on TDL flux is transient. LPT 2 accelerated TDL leukocyte flux from a mean pre-LPT 2 value of 2.3±1.0×106 cells/min to a peak value of 174±17×106 cells/min at 2 min. For 4 min of LPT 2, TDL leukocyte flux averaged 136.8±9×106 cells/min (p<0.001 vs. pre-LPT 2). The flux at post-LPT 2 decreased to 5.8±1.6×106 cells/min (p<0.001). There was no significant (p>0.05) difference in TDL leukocyte flux between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

FIG. 4.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct leukocyte flux. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.05). **Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.01). ***Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

The TDL flux of neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes is reported in Table 2. LPT 1 significantly increased the flux of neutrophils (p<0.001) by 5500%, monocytes by 3294% (p<0.001), and lymphocytes (p<0.001) by 3646%, compared to pre-LPT 1. The flux decreased post-LPT 1 by 98% for neutrophils (p<0.001), 98% (p<0.001) for monocytes, and 98% for lymphocytes (p<0.001) compared to LPT 1. Similarly, LPT 2 significantly increased the flux of neutrophils by 8114% (p<0.001), monocytes by 4491% (p<0.001), and lymphocytes by 5613% (p<0.001), compared to pre-LPT 2 values. Subsequently, the flux decreased following post-LPT 2 by 96% (p<0.001) for neutrophils, 95% (p<0.001) for monocytes, and 96% (p<0.001) for lymphocytes compared to LPT 2. No statistically significant (p>0.05) differences in TDL neutrophil, monocyte, and lymphocyte counts and flux were detected between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

Table 2.

LPT Increases Thoracic Duct Leukocyte Flux

| Pre-LPT 1 | LPT 1 | Post-LPT 1 | Pre-LPT 2 | LPT 2 | Post-LPT 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte flux (× 106 cells/min) | ||||||

| NO |

0.20±0.10 |

11.2±1.86* |

0.18±0.07 |

0.14±0.08 |

11.5±1.06* |

0.46±0.13 |

| MO |

0.66±0.29 |

22.4±4.10* |

0.40±0.16 |

0.44±0.25 |

20.2±2.7* |

1.00±0.36 |

| LY | 3.07±1.15 | 115±28.6* | 2.45±0.51 | 1.74±0.62 | 99.4±11.9* | 4.32±1.12 |

Thoracic duct lymph was collected over ice from five anesthetized dogs and analyzed.

LPT, lymphatic pump technique; LY, lymphocytes; MO, monocytes; NO, neutrophils.

Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases the flux of cytokines and chemokines in thoracic duct lymph

Concentrations of inflammatory mediators in TDL are reported in Table 3. In general, inflammatory mediator concentrations did not significantly change during LPT when compared with pre- and post-LPT, except post-LPT 2 values for IL-6 were statistically greater than pre-LPT 2 (93% increase) and LPT 2 (67% increase). To quantify the effect of LPT on TDL cytokine/chemokine release, we measured three inflammatory mediators previously shown to increase during LPT.14 LPT 1 significantly increased TDL flux of IL-6 (1653%; p<0.001), IL-8 (7223%; p<0.001), and KC (2052%; p<0.001) when compared with pre-LPT 1 (Fig. 5). Subsequently, the flux of these cytokines and chemokines decreased 94% (p<0.001) in IL-6, IL-8, and KC following LPT 1. Similarly, LPT 2 significantly increased TDL flux of IL-6 (2038%; p<0.001), IL-8 (1575%; p<0.001), and KC (1405%; p<0.001) when compared with pre-LPT 2. As seen in post-LPT 1, the flux of cytokines and chemokines in post-LPT 2 declined after cessation of the intervention; IL-6 decreased by 91% (p<0.001), and both IL-8 and KC decreased by 94% (p<0.001). The flux of IL-6 was greater during LPT 2 than during LPT 1 (p<0.001), a reflection of the increased concentration of IL-6 during LPT 2. On average, LPT 2 released 184 pg/min more IL-6 into the thoracic duct lymph compared to LPT 1.

Table 3.

Lymphatic Pump Treatment Did Not Significantly Alter the Concentration of Inflammatory Mediators in TDL

| Pre-LPT 1 | LPT 1 | Post-LPT 1 | Pre-LPT 2 | LPT 2 | Post-LPT 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (pg/mL) |

48±8 |

45±5 |

47±6 |

71±6‡ |

82±5‡ |

137±35‡* |

| IL-8 (pg/mL) |

MDL |

80±9 |

84±8 |

89±6 |

81±2 |

84±14 |

| KC (pg/mL) |

321±47 |

370±55 |

401±62 |

524±65 |

428±38 |

454±66 |

| NO2− (μM) |

6.9±0.8 |

5.4±0.4 |

4.4±0.5 |

5.0±1.2 |

3.6±0.5 |

5.3±1.3 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 3.8±0.2 | 5.0±0.3 | 4.4±0.6 | 4.7±0.5 | 5.0±0.1 | 4.6±0.1 |

Thoracic duct lymph was collected over ice from five anesthetized dogs and analyzed.

IL, interleukin; KC, keratinocyte-derived chemoattractant; LPT, lymphatic pump technique; MDL, minimum detection limits (6.51 pg.ml); NO2−, nitrite; SOD, superoxide dismutase. Data are means±SE (n=5). ‡Greater than respective LPT 1 (p<0.001).*Greater than LPT 2 and Pre-LPT 2 (p<0.001). Repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test.

FIG. 5.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic cytokine and chemokine flux. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001).

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases the flux of superoxide dismutase and nitrite in thoracic duct lymph

Neither LPT 1 nor LPT 2 significantly altered the concentrations of nitrite and SOD in TDL (Table 3). The effect of LPT on SOD flux is presented in Figure 6. LPT increased SOD flux in TDL, 2418% from 1.2±0.07 U/min pre-LPT 1 to 30.21±1.53 U/min during LPT 1 (p<0.001), and 1848% from 1.41±0.15 U/min pre-LPT 2 to 27.46±0.39 U/min during LPT 2 (p<0.001). Post-LPT decreased SOD flux in TDL, 95% to 1.47±0.20 U/min (p<0.001) during post-LPT 1 and 95% to 1.40±0.04 U/min (p<0.001) during post-LPT 2. During the 4 min period of LPT 2, average SOD flux was 2.75 U/min less than compared to the same period of LPT 1.

FIG. 6.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct SOD flux. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) differences between LPT 1 and LPT 2.

The effect of LPT on nitrite flux is presented in Figure 7. LPT 1 increased nitrite flux 1356% in TDL from 2.22±0.27 μM/min pre-LPT 1 to 32.33±2.49 μM /min (p<0.001), and LPT 2 increased nitrite flux 1240% in TDL from 1.50±0.35 μM/min pre-LPT 2 to 20.10±2.98 μM/min (p<0.001). Nitrite flux decreased 96% to 1.46±0.15 μM/min (p<0.001) during post-LPT 1 and 92% to 1.59±0.38 μM/min (p<0.001) during post-LPT 2. During 4 min of LPT 2, average nitrite flux was 12.23 μM/min less than compared to the same period of LPT 1 (p<0.001).

FIG. 7.

Lymphatic pump treatment repeatedly increases thoracic duct nitrite flux. See Figure 1 for protocol details. Data are means±SE (n=5). Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc test. *Greater than respective pre-LPT and post-LPT values (p<0.001). ‡Different from LPT 1 (p<0.001).

Discussion

Animal studies have shown that LPT increased TDL flow in healthy conscious dogs,13 in conscious dogs with abdominal edema induced by inferior vena cava constriction,19 and in conscious dogs after extracellular fluid volume expansion.18 In anesthetized dogs, LPT increased TDL flow, leukocyte count and flux,16 inflammatory mediators,14 and mobilized leukocytes from mesenteric lymph nodes.17 In addition, LPT increased lymph flow and the mobilization of gastrointestinal lymphoid tissue derived leukocyte counts of both dogs and rats.15,17 The aim of the present study was to gain new information on replenishment of LPT-sensitive lymph reservoirs by repeating LPT after a 2 h resting interval. We found both LPT 1 and LPT 2 produced similar increases in TDL flow, TDL leukocyte concentration, and the lymphatic flux of leukocytes and immune mediators. In addition, the results confirmed prior findings that LPT mobilizes TDL flow and immune factors in anesthetized dogs.14,16,17

Our results demonstrate that LPT mobilizes lymph from a reservoir that depletes during 4 min of LPT, but is replenished by 2 h. At rest, the majority of the TDL is derived from the liver (∼30%) and intestines (∼70%),22–24 with small contributions from the thoracic cavity and lower extremities.22,25 Thus, we speculate that during the 2 h resting interval between LPT 1 and LPT 2, this fluid pool was mainly replenished by lymph formed in the abdominal viscera.

LPT repeatedly enhanced the release of leukocytes into lymphatic circulation, as demonstrated by an increase in leukocytes/mL. This increase in leukocyte numbers was seen at 1 min of LPT, suggesting LPT quickly mobilizes leukocytes into lymphatic circulation. While greatly reduced compared to the leukocytes released during LPT, TDL leukocyte concentrations remained elevated at 10 min post-LPT, indicating the LPT-sensitive leukocyte reservoir continues to release cells after the cessation of LPT. Since leukocytes directly kill pathogens or induce an antigen-specific immune response via the lymph nodes,1,3 the ability to repeatedly mobilize leukocytes and other immune factors by repeated LPT should have important clinical implications.

Although the lymphatic flux of SOD was similar during LPT 1 and LPT 2, the flux of NO2−, an index of NO, was reduced during LPT 2. NO in lymph is derived from the lymphatic endothelium, where it regulates phasic contractions and lymph flow.31,32 Specifically, increasing lymph flow induces the production and release of NO from lymphatic endothelial cells.32 LPT did not increase the concentration of NO in TDL. It is possible that NO was released during LPT, but when the lymph flow increased the NO was diluted; therefore, an increase in NO concentration was not seen. Furthermore, the flux of NO during LPT 2 was significantly reduced compared to LPT 1, suggesting it takes more than 2 h to fully replenish the NO precursors in the endothelium.

A high lymph flow rate can also inhibit the intrinsic lymph pump, which is predominantly due to the production of NO.32–35 It has been proposed that this flow-dependent inhibition of the intrinsic active lymph pump may have evolved to save energy when the lymphatics do not need to generate lymph flow, because another upstream mechanism, such as elevated interstitial fluid pressure, is generating flow.35 Therefore, it is possible that the increase in TDL flow/sheer generated during LPT may relax lymph vessel tone and suppress the intrinsic pump, thus sparing pumping energy within the lymphatic system. This would be particularly important during the management of edema; however, further studies are required to support this hypothesis.

While LPT increased the lymphatic flux of cytokines, KC, SOD, and NO2−, it is interesting that LPT failed to significantly increase the lymphatic concentration of these inflammatory mediators. Since their increase was flow-dependent, LPT likely mobilizes lymph pools that contain inflammatory mediators. Exceptions were IL-6 and IL-8. The gradual increase in the lymphatic concentration of IL-6 was not LPT-mediated but more likely related to surgical stress.36–39 In support, IL-6 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that has been shown to increase in the plasma following surgery,36 laparoscopic procedures,37 and cardiopulmonary bypass.39 On the other hand, TDL levels of IL-8 were at the minimal detection limit (6.51 pg/mL) and quickly rose (80±9 pg/mL) in response to LPT 1. Furthermore, IL-8 remained increased during the duration of the experiment. This result suggests that LPT 1 was able to stimulate the continuous release of IL-8 into lymphatic circulation and LPT 2 did not further enhance this release; however, the source of this IL-8 and the mechanism responsible for this increase is not clear.

Previous studies measured the effect of lymph flow/shear on lymph vessel function using isolated pressurized ducts, where transmural pressure and flow were imposed in vitro.32–36 While we did not measure the effect of LPT directly on the function of the lymphatic vasculature, we were able to study the effect of enhancing lymph flow on immune cell concentration and inflammatory mediators in vivo. The increase in lymph flow generated during LPT likely affects lymphatic endothelium; however, further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. A distinct advantage to our model is that it allows us, and others, to examine the effect of enhancing lymph flow on the development and/or resolution of disease in vivo. For example, in support, recent animal studies demonstrated LPT has a positive effect on infection40 and edema.19

Some limitations of the current study must be recognized. While in general, findings in anesthetized animals have been consistent with our more limited observations in conscious instrumented dogs,13,14,16–19 confirmation of the current findings in a conscious model would be valuable. LPT was repeated only once after a 2 h resting interval, due to concern about the stability of the anesthetized animal; therefore, more applications of LPT may continue to enhance the lymphatic system. It is also not known if these LPT-sensitive lymph pools replenish before 2 h. Clearly, a more extensive study with more repetitions of LPT at different intervals, are warranted.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that LPT can be repeated within a 2 h period to stimulate the entry of leukocytes into lymph and mobilize lymph pools containing inflammatory mediators into central lymphatic circulation. This finding provides new insight into the kinetics of lymph formation following manual stimulation. Furthermore, clinical guidelines for the duration and frequency of LPT are inconsistent and poorly defined;5,12,26–30 therefore, the information gained from this study may encourage a more standardized and aggressive use of LPT during the treatment of infection and edema by osteopathic physicians and other manual medicine practitioners.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Grant R01 AT004361 (LMH). The authors thank the Osteopathic Heritage Foundation for their continued support of the Basic Science Research Chair (LMH). The authors would also like to thank Arthur Williams, Jr., and Linda Howard for assistance in the animal surgery.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M, eds. Janeway's Immunobiology. Garland Science, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olszewski WL. The lymphatic system in body homeostasis: Physiological conditions. Lymphat Res Biol 2003;1:11–21; discussion 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parham P. The Immune System. Garland Science, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayerson HS. On Lymph and Lymphatics. Circulation 1963;28:839–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuchera ML. Lymphatics Approach. In: Chila AG, eds. Foundations of Osteopathic Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2011:786–808 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rockson SG. Lymphatic research: Past, present, and future. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:183–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockson SG. The lymphatic continuum revisited. Ann NY Acad Sci 2008;1131:ix–x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witte CL, Witte MH. Disorders of lymph flow. Acad Radiol 1995;2:324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris SR, Hugi MR, Olivotto IA, Levine M. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 11. Lymphedema. CMAJ 2001;164:191–199 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murdaca G, Cagnati P, Gulli R, et al. Current views on diagnostic approach and treatment of lymphedema. Am J Med 2012;125:134–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keeley V. Pharmacological treatment for chronic oedema. Br J Community Nurs 2008;13:S4,S6,S8–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace E, Mcpartland JM, Jones JM, III, Kuchera WA, Buser BR. Lymphatic System: Lymphatic Manipulative Techniques. In: Ward RC, eds. Foundations for Osteopathic Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003:1056–1077 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knott EM, Tune JD, Stoll ST, Downey HF. Increased lymphatic flow in the thoracic duct during manipulative intervention. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2005;105:447–456 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schander A, Downey HF, Hodge LM. Lymphatic pump manipulation mobilizes inflammatory mediators into lymphatic circulation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2012;237:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huff JB, Schander A, Downey HF, Hodge LM. Lymphatic pump treatment augments lymphatic flux of lymphocytes in rats. Lymphat Res Biol 2010;8:183–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodge LM, King HH, Williams AG Jr., et al. Abdominal lymphatic pump treatment increases leukocyte count and flux in thoracic duct lymph. Lymphat Res Biol 2007;5:127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodge LM, Bearden MK, Schander A, et al. Lymphatic pump treatment mobilizes leukocytes from the gut associated lymphoid tissue into lymph. Lymphat Res Biol 2010;8:103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downey HF, Durgam P, Williams AG, Jr., Rajmane A, King HH, Stoll ST. Lymph flow in the thoracic duct of conscious dogs during lymphatic pump treatment, exercise, and expansion of extracellular fluid volume. Lymphat Res Biol 2008;6:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prajapati P, Shah P, King HH, Williams AG, Jr., Desai P, Downey HF. Lymphatic pump treatment increases thoracic duct lymph flow in conscious dogs with edema due to constriction of the inferior vena cava. Lymphat Res Biol 2010;8:149–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: A physiologic messenger molecule. Annu Rev Biochem 1994;63:175–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marzinzig M, Nussler AK, Stadler J, et al. Improved methods to measure end products of nitric oxide in biological fluids: Nitrite, nitrate, and S-nitrosothiols. Nitric Oxide 1997;1:177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mobley WP, Kintner K, Witte CL, Witte MH. Contribution of the liver to thoracic duct lymph flow in a motionless subject. Lymphology 1989;22:81–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris B. The hepatic and intestinal contributions to the thoracic duct lymph. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 1956;41:318–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon AD, Lascelles AK. The intestinal and hepatic contributions to the flow and composition of thoracic duct lymph in young milk-fed calves. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 1968;53:194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanous MY, Phillips AJ, Windsor JA. Mesenteric lymph: The bridge to future management of critical illness. JOP 2007;8:374–399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller CE. Osteopathic principles and thoracic pump therapeutics proved by scientific research. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1927;26:910–914 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholas AS, Nicholas EA. Lymphatic Techniques. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen TW, Pence TK. The use of the thoracic pump in treatment of lower respiratory tract disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1967;67:408–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noll DR, Shores JH, Gamber RG, Herron KM, Swift J., Jr.Benefits of osteopathic manipulative treatment for hospitalized elderly patients with pneumonia. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2000;100:776–782 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noll DR, Degenhardt BF, Morley TF, et al. Efficacy of osteopathic manipulation as an adjunctive treatment for hospitalized patients with pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Osteopath Med Primary Care 2010;4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bohlen HG, Wang W, Gashev A, Gasheva O, Zawieja D. Phasic contractions of rat mesenteric lymphatics increase basal and phasic nitric oxide generation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009;297:H1319–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsunemoto H, Ikomi F, Ohhashi T. Flow-mediated release of nitric oxide from lymphatic endothelial cells of pressurized canine thoracic duct. Jpn J Physiol 2003;53:157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gashev AA, Davis MJ, Zawieja DC. Inhibition of the active lymph pump by flow in rat mesenteric lymphatics and thoracic duct. J Physiol 2002;540.3:1023–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasheva OY, Zawieja DC, Gashev AA. Contraction-initiated NO-dependent lymphatic relaxation: A self-regulatory mechanism in rat thoracic duct. J Physiol 2006;575.3:821–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaweija DC. Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphat Res Biol 2009;7:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruickshank AM, Fraser WD, Burns HJ, Van Damme J, Shenkin A. Response of serum interleukin-6 in patients undergoing elective surgery of varying severity. Clin Sci (Lond) 1990;79:161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jakeways MS, Mitchell V, Hashim IA, et al. Metabolic and inflammatory responses after open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 1994;81:127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenkin A, Fraser WD, Series J, et al. The serum interleukin 6 response to elective surgery. Lymphokine Res 1989;8:123–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitten CW, Hill GE, Ivy R, Greilich PE, Lipton JM. Does the duration of cardiopulmonary bypass or aortic cross-clamp, in the absence of blood and/or blood product administration, influence the IL-6 response to cardiac surgery? Anesth Analg 1998;86:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hodge LM. Osteopathic lymphatic pump techniques to enhance immunity and treat pneumonia. Int J Osteopath Med 2012;15:13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]