Abstract

In vivo, epithelial cells are connected both anatomically and functionally with stromal keratocytes. Co-culturing aims at recapturing this cellular anatomy and functionality by bringing together two or more cell types within the same culture environment. Corneal stromal cells were activated to their injury phenotype (fibroblasts) and expanded before being encapsulated in type I collagen hydrogels constructs. Three different epithelial-stromal co-culture methods were then examined: epithelial explant; transwell; and the use of conditioned media. The aim was to determine whether the native, inactivated keratocyte cell phenotype could be restored in vitro. Media supplementation with transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1) was then used to determine whether the inactivated stromal cells retained their plasticity in vitro and could be re-activated to the fibroblast phenotype. Finally, media supplementation with wortmannin was used to inhibit epithelial–stromal cell interactions. Two different nondestructive techniques, spherical indentation and optical coherence tomography, were used to reveal how epithelial-stromal co-culturing with TGF-β1, and wortmannin media supplementation, respectively, affect stromal cell behavior and differentiation in terms of construct contraction and elastic modulus measurement. Cell viability, phenotype, morphology, and protein expression were investigated to corroborate our mechanical findings. It was shown that activated stromal cells could be inactivated to a keratocyte phenotype via co-culturing and that they retained their plasticity in vitro. Activated corneal stromal cells that were fibroblastic in phenotype were successfully reverted to a nonactivated keratocyte cell lineage in terms of behavior and biological properties; and then back again via TGF-β1 media supplementation. It was then revealed that epithelial–stromal interactions can be blocked via the use of wortmannin inhibition. A greater understanding of stromal–epithelial interactions and what mediates them offers great pharmacological potential in the regulation of corneal wound healing, with the potential to treat corneal diseases and injury by which such interactions are vital.

Introduction

Most tissues consist of more than one cell type, and it is the cellular interplay and organization that are essential to normal development, homeostasis, and function; for example, transparency in corneal tissue. In vivo, corneal epithelial cells are in close contact, anatomically and functionally,1 with stromal keratocytes.2,3 In vivo studies have demonstrated that epithelial cells coordinate with the keratocytes in the adjoining stromal layer via bidirectional-soluble release mechanisms, although direct cell–cell communications occur in some situations.4 The process occurs simultaneously, in a highly coordinated manner that changes depending on development, homeostasis, and wound healing. For example, in vivo, epithelial destruction or a loss of contact between the epithelial and stromal cells can augment an injury response. This often results in a fibroblastic “activation” of the normally quiescent keratocytes.5–7 This stromal cell activation can be easily mimicked in vitro by culturing stromal cells in the presence of serum8,9 or transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1); and this strategy is often employed to culture large numbers of stromal cells. However, this “activated,” proliferative, fibroblastic phenotype is markedly different from the native, “inactive,” quiescent keratocyte phenotype in terms of cell behavior and matrix metabolism. Thus, the resulting tissue-engineered corneal or biomimetic tissue constructs seeded with these activated, fibroblastic cells often mimic scarred native tissue.

In vivo the cornea is capable of both fibrotic and regenerative wound healing responses. The different wound healing and remodeling mechanisms result in either an opaque, disorganized tissue or a functional transparent tissue, respectively, which has been linked to stromal cell activation and inactivation. A fundamental challenge of corneal biology is to understand and assist tissue regeneration as opposed to fibrosis. Epithelial–stromal cellular interactions and what mediates them play a great role in this.

Co-culture systems act as powerful in vitro tools for studying tissue cellular interactions and function; however, they often lack realistic spatial resolution. Two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cultures are often used to investigate the way in which various exogenous growth factors regulate growth, differentiation, and function of corneal cells.10 However, monolayer cultures often lack the three-dimensional (3D) physiological environment found in vivo and so have a limited application to the in vivo milieu.11 Thus, a 3D environment may be more applicable to mimic the extrinsic environmental as well as the intrinsic cellular cues that are necessary to successfully culture corneal stromal cells in their native, inactive keratocyte phenotype.

The aim of this study is to investigate the role of epithelial–stromal cell signaling for the control and restoration of corneal stromal cell phenotype in a 3D model. We investigate the nature of epithelial–stromal cell contact, cell signaling molecules, and the inhibition of critical pathways in controlling stromal cell phenotype and the biomechanical nature of keratocyte plasticity using our nondestructive monitoring tools.12,13 These data have then been compared with cell viability, phenotype, morphology, and protein expression.

Materials and Methods

Adult human-derived corneal stromal cell culture

Adult human corneal tissue remaining from corneal transplantation (the corneal rim) was used for the isolation of adult human-derived corneal stromal (AHDCS) cells. The central corneal button had been removed, leaving only the remaining limbal tissue as a cell source. This research has received approval from Birmingham NHS Health Authority Local Research Ethics Committee with informed signed donor consent. The endothelial and epithelial layers were stripped using sharp-point forceps. The remaining stroma was cut into smaller pieces and cultured in cell culture flasks containing Dulbecco's-modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Biowest) supplemented with fetal calf serum (10% [v/v]; Biowest), antibiotic and antimitotic solution (1% [v/v]; Sigma-Aldrich), and L-Glutamine (2 mM; Sigma-Aldrich), referred to as fibroblast media, at 37°C, 5% CO2, allowing AHDCS cells to become activated to a fibroblastic phenotype, proliferate and migrate out from the tissue. Third passage cells were used for all experiments.

Epithelial cell culture

Adult porcine eyes were obtained from a local abattoir (SMP) within 2 h postmortem and dissected within 1 h of acquisition. The epithelial layer was stripped using sharp point forceps (Fig. 1D). The epithelial tissue from the peripheral cornea that is the limbal region, was dissected into sections ∼2 mm in diameter. Five to six pieces of limbal epithelium were carefully placed posterior side down onto fibronectin (Fn)-coated surfaces as appropriate and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2. Epithelial media consisted of CnT20 PCT Corneal Epithelium Medium, defined, supplemented with solution A, B, and C (CnT20; CellNTec, Precision Media and Models).

FIG. 1.

Schematic drawing of the experimental design and set-up of different mono- and co-culture environments. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Hydrogel fabrication and stromal cell seeding of constructs

Rat tail collagen type I (BD Bioscience, Mountain Science) hydrogels were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions as previously described,14 using 10×DMEM in place of PBS. Collagen mixture (500 μL at 3.5 mg/mL) was cast into a filter paper ring (internal diameter 20 mm) on nonadherent PTFE plates. The AHDCS cells were suspended throughout the hydrogel solution before gelation (cell density; 1×106 cells/mL) (Fig. 1A). Gelation was achieved by incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 30–45 min. All stromal cell-seeded hydrogel constructs were seeded in serum-containing fibroblast media for the first 24 h of culture (Fig. 1B). Monoculture control hydrogel constructs were also prepared by which stromal cell-seeded hydrogel constructs were cultured under serum-containing fibroblast media alone (Fig. 1I) or serum-free CnT20 media alone (Fig. 1J).

Fn coating

Human plasma Fn (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared at a concentration of 10 ng/μL in PBS. Each cell-seeded collagen hydrogel was washed twice in PBS before being submerged in 500 μL Fn solution (Fig. 1C). Tissue culture plastic (TCP) T25 cm2 flasks were coated using 3 mL of the solution (Fig. 1E), and 1 mL Fn solution was used to coat the permeable membrane of the insert dishes (Fig. 1F). The constructs, TCP, and culture inserts were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h.

Epithelial–stromal co-culture

The stromal co-culture experiments were split into three groups: explant; transwell, and conditioned media cultures. Explant cultures referred to epithelial tissue explants that were transferred straight onto Fn-coated stromal cell-seeded hydrogel constructs (Fig. 1G) cultured under 3 mL CnT20 media. Transwell cultures referred to stromal cell-seeded collagen constructs that were placed into sterile six-well companion plates (BD Falcon) below a permeable cell culture insert dish (pore size 0.4 μm; BD Falcon) onto which epithelial explants were cultured (Fig. 1F) under 3 mL CnT20 media. Conditioned media were obtained by seeding epithelial explants onto Fn-coated T25 cm2 TCP flasks and allowing them to reach confluence (Fig. 1E). The spent media (5 mL per flask) were collected. It was sterile filtered and pH balanced using HEPES-buffered saline solution (Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich) before being mixed with CnT20 media at 10% (v/v) concentration. Three microliter of conditioned media was added to each collagen construct (Fig. 1H). Media were changed every 3 days for each co-culture experiment.

Treatment with TGF-β1

In order to determine as to whether the corneal stroma cells retained their plasticity, TGF-β1 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to supplement all culture media at a concentration of 10 ng/mL, after 14 days of mono- or co-culturing, respectively. All constructs were cultured for a further 7 days in TGF-β1 supplemented media before the experiment was terminated at day 21.

Inhibition of cell–cell signaling with wortmannin

Wortmannin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to supplement all media at a concentration of 10 ng/mL to determine whether the effect of co-culturing could be blocked. All constructs were cultured for 14 days, after the supplementation with wortmannin at day 2 in the experiment.

Cell viability and morphology

Cell viability was observed at day 7 and 14 in co-cultured constructs; day 21 in TGF-β1-treated constructs; and day 14 in wortmannin-treated constructs using a live-dead fluorescent double staining kit (Fluka); it was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. A five-hundred-microliter staining solution was used per construct. Stained hydrogel constructs were washed in PBS and examined using fluorescent microscopy (Eclipse Ti-S; Nikon). Epithelial cell outgrowth and morphology was observed using light microscopy (Olympus CKX41).

Construct contraction

Hydrogel constructs cast into filter paper rings were effectively confined to the dimension of the filter paper ring. This permitted analysis of confined contraction in terms of a change of thickness of the hydrogel construct via optical coherence tomography.13 Constructs were examined every 1–2 days over 14–21 days in culture, depending on when/if exogenous factors were used to supplement media.

Modulus measurement

The mechanical properties of the constructs were measured using a nondestructive spherical indentation technique,15,16 which permitted repeated analysis of constructs over time. Hydrogel constructs were circumferentially clamped. A PTFE sphere (0.0711 g and 2 mm radius) was placed centrally on the construct, causing uniform deformation of the hydrogel. The extent of the deformation was recorded and applied to a theoretical model17 to calculate the elastic modulus of the constructs. Modulus measurements were performed on all samples apart from the explant co-cultured constructs (Fig. 1G). The tissue explants meant that the surface of the construct was nonhomogeneous; thus, the spherical indenter was unable to spontaneously centre18 and axisymmetrical deformation did not occur. The elastic modulus was measured every 1–2 days for 14 or 21 days depending on the experimental group being investigated.

Immunolabeling of epithelial and stromal cell cultures

Cell phenotype was observed in both epithelial and stromal cell 3D cultures. In addition, a sample of activated stromal cells that remained in 2D monoculture under serum-containing fibroblast media was analyzed. Each sample was fixed in 500 μL 10% neutral-buffered formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min, before washing×3 in PBS. The samples were permeabilized with 500 μL 0.1% Triton®×100 (in PBS) for 60 min before washing×3 in PBS. Samples were then blocked with 500 μL 2% bovine serum albumin (2% w/v in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h. Samples were then washed×3 in PBS before staining with the primary antibody at dilution 1:50 (in PBS) overnight at 4°C. All primary and secondary antibodies were purchased from SantaCruz Biotechnology unless otherwise stated.

The primary antibodies used to stain epithelial cultures were cytokeratin-3 goat polyclonal IgG (CK3) and vimentin goat polyclonal IgG. The samples were then washed five times in PBS in 5 min intervals. The primary antibodies used to stain the stromal cell cultures were split into two panels: keratocan, aldehydedehydrogenase-3 (ALDH3) and lumican to act as a positive stain for the keratocyte phenotype and FITC-conjugated Thy-1, alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and vimentin were used to positively stain the fibroblast/myofibroblast phenotype. Donkey anti-goat IgG-FITC, donkey anti-mouse IgG FITC, donkey anti-goat IgG-TRITC, and goat anti-mouse IgG TRITC were used as secondary antibodies to fluorescently label the samples at dilution 1:100 (in PBS) for 4 h at 4°C in the dark. All samples were counterstained with DAPI (1:500; prepared in PBS; Sigma-Aldrich) and examined using fluorescent microscopy (Eclipse Ti-S; Nikon).

Statistics

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism®. The data were subjected to a normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnoff) test. The data were normally distributed, so comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey post-tests. Significance was indicated to determine whether the effects of time, media, and epithelial culture method were statistically significant at three levels: *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, and ***p≤0.001. All results are expressed as a mean value (n=6)±the calculated standard deviation.

Results

The role of epithelial cultures in stromal cell differentiation

Cell viability

Cell viability was monitored at day 7 and 14 for both epithelial and stromal cells when cultured in different mono- and co-culture environments. Cell viability in all epithelial cultures remained high at both 7 and 14 days (Fig. 2A–F). In stromal cell monocultures, cell viability was high in constructs cultured in serum-containing fibroblastic media at both 7 and 14 days (Fig. 2K, P). However, stromal cell-seeded constructs cultured in serum-free CnT20 monoculture had a higher proportion of dead cells after 7 days of culture (Fig. 2J) compared with all other constructs; and after 14 days of culture, most of the stromal cells within the construct were dead (Fig. 2O). In co-cultured samples, high cell viability was maintained in all stromal cell cultures in explant, transwell, and conditioned media cultures for 7 days (Fig. 2G, H and I). This high stromal cell viability was maintained in the explant and transwell cultures for 14 days (Fig. 2L, M). A drop in stromal cell viability was observed in the conditioned co-cultured constructs after 14 days (Fig. 2N), although overall stromal cell viability was still higher than observed in CnT20 monocultures.

FIG. 2.

The effect of different mono- and co-culturing on epithelial (A–F) and stromal (G–P) cell viability; scale bar=100 μm; The average thickness of cellular constructs (Q) demonstrated that the constructs cultured under serum-containing fibroblast media contracted significantly more than all other constructs cultured in serum-free CnT20 media from day 2 onwards, ***p≤0.001; The average thickness of all acellular scaffolds (R) remained constant; The average elastic modulus of cellular constructs (S) demonstrated that the modulus of all constructs cultured in serum-containing fibroblast media were significantly greater than all other constructs from day 2 onward, ***p≤0.001, and that in the serum-free constructs, the modulus of the transwell constructs was significantly greater at day 9 and 14, ***p≤0.001 compared with the CnT20 monocultured and conditioned media constructs; the average elastic modulus of acellular scaffolds (T) remained constant. n=6; represented as a mean value±the calculated SD. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Construct contraction

All cellular constructs were cultured in serum-containing fibroblast media for the first 24 h. This resulted in an initial contraction of all constructs, manifesting as a reduction in the thickness of the constructs. The thickness of all constructs reduced by ∼15% (Fig. 2Q), which was significantly thinner than the acellular control scaffolds (Fig. 2R). The thickness of all subsequent constructs switched to the CnT20 culture media, irrespective of the culture method employed, remained constant for the duration of the experiment. The constructs that remained in serum-containing fibroblast media continued to contract for the duration of the experiment, with most contraction occurring in the first week. The resulting constructs were ∼30% of their original thickness at day 14. ANOVA tests revealed that change to CnT20 media had a significant effect on the change in thickness of the construct. After 2 days in culture, constructs cultured in fibroblast media contracted and reduced significantly more in thickness compared with all other constructs (p≤0.001). No significant difference in construct thickness was observed between any construct cultured in CnT20 media. The construct thickness of all acellular scaffolds remained constant for 14 days.

Modulus measurement

The elastic modulus measurement was used to measure the stiffness of the constructs, which refers to the constructs' ability to resist deformation. The modulus of the constructs cultured in serum-containing fibroblast media increased over the duration of the experiment and was significantly greater (p≤0.001) than all other constructs from day 2 onward (Fig. 2S). The modulus of the transwell constructs was significantly greater (p≤0.001 at day 9 and 14; p≤0.05 at day 10 and 11) than monocultured specimens in CnT20 media and co-cultured conditioned media constructs (p≤0.05 at day 9 and 10; p≤0.001 at day 14). The modulus of the transwell constructs remained relatively constant for 14 days, whereas the modulus reduced in both CnT20 monocultured and conditioned media co-cultured constructs after 9 days of culture. There was no significant difference in the modulus of constructs cultured in CnT20 monoculture compared with conditioned media constructs. The modulus of all acellular control scaffolds remained constant at ∼0.9 kPa for 14 days (Fig. 2T).

Protein marker expression

All epithelial cultures were immunohistochemically characterized using primary antibodies CK3 and vimentin after 14 days of culture. CK3 is a specific corneal epithelial marker19–21; and vimentin has been shown to be expressed in injured epithelial cells.6 All samples stained positive for CK3 (Fig. 3A–C) and negative for vimentin (Fig. 3D–F). There was no apparent difference in CK3 expression detected in the samples.

FIG. 3.

The effect of different co-culturing methods on CK3 (A–C) and vimentin (D–F) gene marker expression in epithelial cells; representative stained cells, imaged using fluorescent microscopy after 14 days of culture. All epithelial cells stained positive for CK3 (A–C) and negative for vimentin (D–E), irrespective of the culture conditions used. Activated stromal cell control staining showed negative expression of CK3 (G) and positive expression of vimentin (H). Scale bar=50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

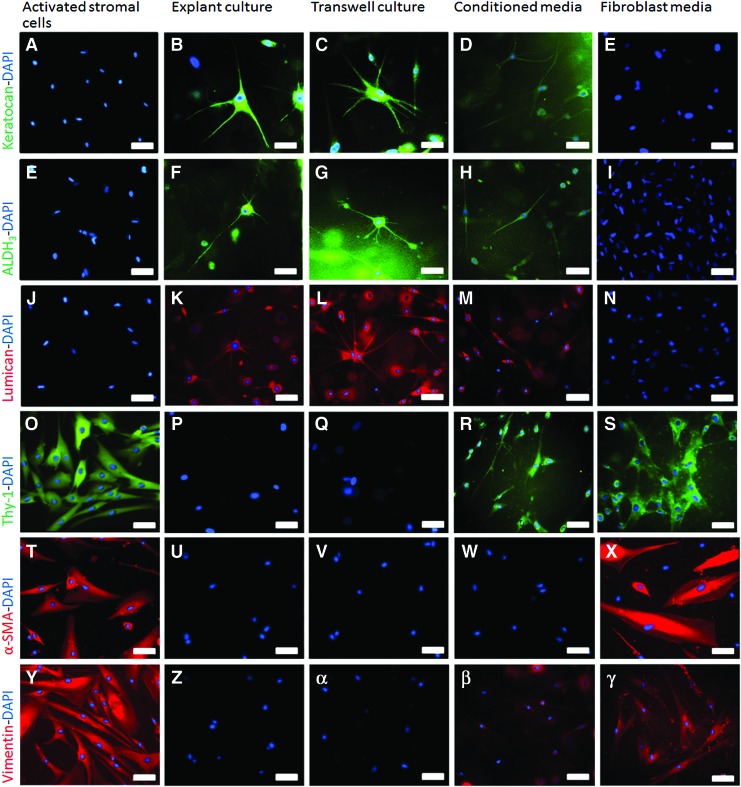

Immunohistochemistry was performed on stromal cells before encapsulation in the hydrogel constructs, that is, while in 2D monoculture and again after 14 days of hydrogel culture except for cells cultured in CnT20 monoculture. The cell viability of these specimens was so poor at day 14 that they were unsuitable for further characterization. Fluorescent markers keratocan, ALDH3, and lumican were used to positively stain for the inactivated keratocyte cell phenotype (Fig. 4A, E, J). No keratocyte markers were detected in the 2D cultured activated stromal cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that expression of these markers is not detected in activated, stromal cell repair subtypes in situ or after culture in serum.22 All three keratocyte markers were positively expressed in explant, transwell, and conditioned media co-cultured stromal cells (Fig. 4B–D, F–H, K–M); however, the level of fluorescence for all the markers appeared lower in the cells cultured in conditioned media (Fig. 4D, H, M) in comparison to explant and transwell co-cultured stromal cells. Subjective observations when taking the images suggested that ∼60–70% of the stromal cells present in both explant and transwell co-cultures were expressing the keratocyte markers keratocan, ALDH3, and lumican. In comparison, only 20–30% of stromal cells in the conditioned media co-cultures were expressing these markers. No keratocyte markers were detected in the fibroblastic monocultured cells (Fig. 4E, I, N).

FIG. 4.

The effect of 3D co-culture and mono-culture on keratocyte (B–E, F–I, K–N) and fibroblast (P–S, U–X, Z–γ) protein marker expression in comparison to activated (fibroblastic) stromal cells grown in a 2D monolayer (A, E, J, O, T, Y); imaged using fluorescent microscopy after 14 days of culture; scale bar=50 μm. 2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Fluorescent markers Thy-1, vimentin, and α-SMA were used to positively stain for fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cell phenotypes. All have previously been utilized to demonstrate the activated repair subtypes of corneal stromal cells.8,20,22 All of these markers were positively detected in the 2D-activated stromal cells (Fig. 4O, T and Y) before 3D hydrogel encapsulation. None of these markers were expressed in either the explant or transwell co-cultured cells (Fig. 4P, Q, U, V, Z, α). All markers were positively detected in the fibroblastic monocultures (Fig. 4S, X, γ). Interestingly, low levels of both Thy-1 and vimentin were detected in the conditioned media co-cultured cells (Fig. 4R, β). α-SMA was only detected in the fibroblast monocultured cells (Fig. 4X) after 3D encapsulation and culture.

The morphology of the stromal cells cultured in fibroblastic monocultures (Fig. 4S, X and γ) was significantly different from the co-cultured cells. The cells in explant and transwell co-cultures, in particular, were much smaller, with multiple dendritic processes (Fig. 4B, C, F, G, K, L) compared with the larger, spindle-shaped cells observed in the fibroblast monocultures. Although the stromal cells were smaller and more elongated in the conditioned co-cultured constructs (Fig. 4D, H, M, R), they lacked the multiple dendritic processes associated with keratocyte morphology.

TGF-β1 regulation of stromal cell plasticity

Cell viability

Stromal cell viability after TGF-β1 supplementation after 14 days of culture was monitored at day 21 (Fig. 5A–E). Stromal cell viability was high in all constructs except those cultured in CnT20 monoculture (Fig. 5C). It was assumed that all these cells had died before TGF-β1 supplementation, as in the previous experiments. The action of TGF-β1 on the epithelial cells appeared to be very potent in that although it did not significantly reduce the epithelial cell viability, the epithelial outgrowth and proliferation was significantly reduced (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

The effect of TGF-β1 (A–E) and wortmannin supplementation (F–J) on cell viability at day 21 and 14, respectively; scale bar=100 μm; the average thickness change (K, M); and the average elastic modulus (L, N) of cellular constructs; n=6; data represented as the mean value±the calculated SD. Epithelial outgrowth in nonsupplemented (O) and wortmannin supplemented (P) co-cultures, scale bar=200 μm. TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta-1. ***Indicates p<0.001. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Construct contraction

TGF-β1 supplementation at day 14 caused a significant decrease in the thickness of all constructs by day 15, except those cultured in CnT20 monoculture (Fig. 5K). Constructs co-cultured in explant, transwell, and conditioned media showed a significant decrease in thickness compared with the value before TGF-β1 supplementation. Both explant and transwell co-cultured constructs contracted significantly more than the conditioned media constructs (p≤0.001 day 15–21). There was no significant difference in the thickness of the explant and transwell co-cultured constructs. As in the initial experiments, the constructs cultured in serum-containing fibroblast media monoculture contracted significantly more than all other constructs (p≤0.001 days 2–21 inclusive).

Modulus measurement

TGF-β1 supplementation increased the modulus of all constructs in all culture conditions with the exception of those monocultured under CnT20 media (Fig. 5L). The trend for monocultured constructs under fibroblast media to have a significantly higher modulus compared with all other constructs was repeated till day 14. TGF-β1 supplementation triggered a sharp increase in the elastic modulus of the constructs at day 15 and also caused an increase in the previously constant modulus of the co-cultured constructs in transwell and conditioned media. By day 21, both co-cultured constructs had a significantly greater modulus than those cultured in CnT20 monoculture (p≤0.05). Although the modulus of the co-cultured transwell constructs appeared higher than that of the conditioned media constructs from days 15–21, the difference was insignificant. The modulus of the CnT20 monocultured constructs was constantly lower from day 7 onward. There was no response to TGF-β1 in these constructs.

Protein marker expression

After 14 days of culture under different culture conditions and a further 7 days of culture after TGF-β1 supplementation, all constructs were stained with a panel of keratocyte/fibroblastic markers (Fig. 6). The constructs monocultured using CnT20 media alone were omitted due to poor cell viability. TGF-β1 supplementation significantly affected the protein expression of all co-cultured constructs, resulting in none of the keratocyte markers being expressed (Fig. 6A–C, E–G, I–K). Conversely, all fibroblastic markers, including α-SMA, were expressed in all constructs, irrespective of the culturing conditions (Fig. 6M–X). Although the levels of protein were not quantified, subjective observations suggest that the expression of the fibroblastic protein markers, Thy-1 and vimentin in particular, were higher in the fibroblastic monocultures (Fig. 6P, X respectively) when compared with explant and transwell co-cultured stromal cells.

FIG. 6.

The effect of TGF-β1 media supplementation on keratocyte and fibroblast protein marker expression in stromal cells; representative stained cells, imaged using fluorescent microscopy of collagen hydrogel constructs at 21 days; scale bar=50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

TGF-β1 supplementation resulted in large and fusiform stromal cell morphologies, characteristic of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cell phenotypes.

Blocking of cellular interactions using wortmannin

Cell viability

Stromal cell viability in response to wortmannin supplementation after 2 days of culture was monitored at day 14 (Fig. 5F–J). The viability of all stromal cells, except those monocultured in fibroblast media (Fig. 5J), was poor and all the cells stained dead. Observations of epithelial cell viability at day 14 suggested that although the epithelial cultures were still viable after 12 days of wortmannin supplementation (data not shown), the outgrowth and migration onto the collagen hydrogels and insert membranes (Fig. 5O, P) in the explant and transwell co-cultures, respectively, was significantly reduced. In addition, there was a morphological difference observed between the epithelial cultures when comparing wortmannin supplemented cultures with nontreated cultures. The nontreated epithelial cells displayed the typical cobblestone morphology Fig. 5O) with tight cell-cell junctions; whereas the wortmannin-treated corneas were much smaller, less flattened in their appearance, and were lacking in the tight cell–cell junction (Fig. 5P).

Construct contraction

Wortmannin supplementation had no apparent effect on the contractile behavior of any of the constructs when compared with the previous experiments investigating the effects of co-culturing alone. No significant differences were observed in the construct thickness of any of the experimental groups for the duration of the experiment with the exception of constructs cultured in fibroblast media monoculture (Fig. 5M); they contracted significantly more than all other constructs from day 2 onward (p≤0.001).

Modulus measurement

Wortmannin supplementation did not have an obvious effect on the modulus of any of the constructs (Fig. 5N). The only exception was the slight drop in modulus of the transwell and conditioned media co-cultured constructs at day 9. Wortmannin supplementation did not change the modulus pattern and magnitude of the monocultured constructs under fibroblast media at all.

Protein marker expression

Stromal cell viability was so poor in all samples treated with wortmannin that further characterization was not possible. The only exceptions were the constructs monocultured in fibroblast media that stained positive for all fibroblastic markers as observed in both previous experiments (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we provide evidence that epithelial–stromal cell signaling is the most eminent cue to regulate stromal cell phenotype in a 3D model. In addition, we have demonstrated our ability in vitro to control the plasticity of corneal stromal cells from an activated, fibroblastic phenotype to an inactivated keratocyte phenotype and reversal in 3D culture. Media supplementation with TGF-β1 can supersede epithelial–stromal crosstalk causing co-cultured stromal cells that are keratogenic in lineage to become re-activated and revert to an injury, fibroblastic cell phenotype. Likewise, we have shown that it is possible to inhibit keratocyte inactivation or differentiation of co-cultured cells via the blocking of epithelial cells' activities by the use of wortmannin.

Biochemical cues for restoring keratocyte phenotype

Our previous research alongside others has revealed that in vitro culture in serum-free media can regulate corneal stromal cell phenotype to a keratocyte lineage.9,14,23,24 CnT20 is a serum-free medium originally developed for epithelial culture, which in this report we demonstrate can also be a good medium for the differentiation of activated stromal cells toward a native, inactivated keratocyte lineage. However, we have gone further to demonstrate that CnT20 medium alone cannot maintain the cell viability of corneal stromal cells for prolonged culture periods; thus, used alone, it cannot promote keratocyte differentiation or inactivation. In contrast, co-culture of stromal cells with epithelial cells under CnT20 medium not only restored the inactivated keratocyte phenotype in terms of cell morphology and protein expression of previously activated stromal cells, but also sustained high cell viability for 14 days.

The use of transwell co-cultures is well documented and has been previously used to determine whether injured epithelial cells are capable of stimulating stromal cell myodifferentiation.6 This study demonstrated that injured corneal epithelial cells secrete soluble factors which are capable of instigating collagen gel contraction, proliferation, and myodifferentiation of stromal cells. In our investigation, we have further demonstrated these findings in vitro that normal epithelia is also responsible for the restoration of the inactivated keratocyte cell phenotype; and through the addition of exogenous soluble factors (TGF-β1 and wortmannin), we can reverse or block this phenotype change in a model tissue equivalent.

Epithelial cells mediate through soluble factors

In this study, we have shown how a co-culture using explant or transwell culture techniques shows a similar response in keratocyte inactivation with regard to protein expression and mechanical behavior, which indicates that the cellular interactions are mostly mediated through soluble molecules.

It has been established in vivo that epithelial–stromal interactions are pivotal determinants of corneal function via highly coordinated mechanisms that maintain normal development, homeostasis, and wound-healing response.1 Specifically, the cellular communication aids in the restoration of activated stromal cells (fibroblasts) back to an inactivated, quiescent keratocyte phenotype after repairing, thus restoring tissue transparency which avoids excessive scarring. It is believed that the cells communicate via the release of soluble factors such as proteoglycans, glycoaminoproteins, and growth factors in a reciprocal, bidirectional manner. Using this principal, we aimed at examining how epithelial cells interact with stromal cells via the inclusion of different epithelial culture conditions from the use of explant, transwell to conditioned media co-cultures on our previously described stromal layer model.14,16

The restoration of the inactivated keratocyte phenotype, as determined by protein marker expression and cell morphology, was greater in the transwell and explant co-cultured stromal cells when compared with the conditioned media constructs. The use of a low concentration of conditioned media suggests that although the soluble factors collected and included in the conditioned media have the ability to partially inactivate or de-differentiate the activated stromal cells to a keratocyte phenotype, the differentiation/inactivation is incomplete. Furthermore, the fact that those stromal cells in conditioned media cultures expressed both keratocyte and fibroblastic markers suggests that the stromal cells may undergo a transient “transitional state” by which the stromal cells have characteristics of both the activated and nonactivated cell phenotypes. In fact, it is not impractical to assume that there are more than three stromal cell phenotypes. Jester and Jin have previously suggested that there may be more than one type of fibroblastic stromal cell phenotype which participates in wound healing.8 Likewise, a similar phenomenon has also been demonstrated by which it has been shown that it is possible to partially de-differentiate or inactivate serum-activated stromal cells toward a quiescent keratocyte phenotype, while still retaining some of their fibroblastic tendencies.14

It is possible that the concentration of soluble factors within the conditioned media used in our experiments was too low to initiate complete restoration of the keratocyte phenotype. We calculated that the stromal cells in the explant and transwell cultures were potentially subject to more than twice as many soluble factors compared with the stromal cells in the conditioned media co-cultures. To do this, we took into account the ratios of confluent epithelial cells, to the surface area that they were grown on, in comparison to the volume of media used. The same volume of media was used in all samples, and the same numbers of stromal cells were seeded into all hydrogel constructs; thus, in order to initiate the same differentiation response, the total volume of soluble factors should be equivalent. In order to test this, our next step would be to test the dose response of conditioned media to determine whether there is an optimal conditioned media dose that can initiate a more “complete” restoration of the keratocyte phenotype.

Another explanation is that the epithelial–stromal signaling mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. It has been previously suggested that the growth factors and cytokines secreted by the epithelial cells regulate the function of stromal cells and vice versa,6,25 that is, the action of one may depend or mediate the expression of the other26 via dynamic feedback loops. Thus, in order for the restoration of the native keratocyte cell phenotype in vitro to take place, both cell types need to be present within the same culture environment.

Biomechanical properties are a sensitive marker of stromal cell phenotype

Assessment of construct contraction in combination with elastic modulus measurements enabled us to nondestructively identify the effects of stromal–epithelial interactions on stromal cell differentiation over prolonged culture periods. The ability to measure matrix contraction in 3D hydrogel constructs can inform us of the phenotype of cultured stromal cells in response to different culture conditions.14,16 Keratocytes are noncontractile, fibroblasts that are moderately contractile, and myofibroblasts are highly contractile.27 When used in combination with modulus data, the mechanical findings provided a more descriptive insight into what was happening at a cellular level within the constructs and at different culture times. However, the lack of contraction and simultaneous reduction in modulus measurement, for example, occurring in both the conditioned and CnT20 monocultured specimens, could be linked to reduced cell viability. To discern whether reduced contraction was due to cell death or epithelial–stromal cell interactions, we assessed cell viability in all constructs. We have found that the lack of contraction and constant modulus measurement in the transwell co-cultured constructs coincided with quiescent, but viable cell types. Such global assessments have been further corroborated by cell morphology and cytoskeletal organization. The protein expression precisely matched the measured biomechanical properties, indicating that biomechanical properties are a sensitive marker of stromal cell phenotype.

Epithelial–stromal interactions can be inhibited

Using wortmannin, a known inhibitor of epithelial–stromal interactions, we have demonstrated that epithelial restoration of the keratocyte cell phenotype can be blocked. Although blocking agents such as wortmannin may have multiple effects on cell signaling pathways, the inhibitory effect of wortmannin with regard to epithelial cell activities has been demonstrated in numerous studies,28–30 often manifesting as delayed corneal wound repair. Wortmannin exposure has been shown to block epithelial proliferation and the release of important growth factors and cytokines, which may ultimately affect stromal cell growth, behavior, and differentiation, depending on what stage of wound healing the cells are in.31,32 Our results were in agreement with these studies in that we observed that epithelial outgrowth and morphology was significantly altered in wortmannin-treated cultures in comparison to nontreated cultures. It may also be possible that wortmannin exposure alone has an effect on keratocyte differentiation of in vitro cultured stromal cells. However, to our knowledge, no one has investigated this yet.

After wortmannin supplementation, all constructs, except those cultured in serum-containing fibroblast media, ceased to contract, a phenomenon that was previously linked to quiescent, keratocyte cell behavior, either caused by a keratogenic differentiation or cell death. In this instance, quiescence was linked to cell death. This was first indicated by the drop in modulus of all constructs cultured in serum-free media after ∼9 days in culture and confirmed by live-dead staining. In vivo, when loss of communication occurs between the epithelial cells and stromal cells, whether the cause be injury, surgery, or disease, a “re-expression” of usually dormant genes, proteins, and growth factors is initiated.11 This leads to an activation and differentiation of the stromal cells, causing them to become fibroblastic, with histological changes to the keratocytes occurring.33 However, this was not the case in this study. A possible explanation is that in blocking the release of cellular communication and soluble cytokines, the stromal cells were effectively in an environment comparable to CnT20 monoculture. As deduced from the co-culture experiments, CnT20 medium alone was not sufficient in sustaining stromal cell growth for prolonged cultures. Thus, cell death occurred in all constructs except those in serum-containing fibroblast medium.

Stromal cells retain their plasticity in 2D and 3D

Since native keratocytes may originate from a population of cranial neural crest cells34 that are capable of regenerative healing, it has been hypothesized that they retain stem cell-like properties. We have shown that despite prolonged culture periods in vitro, corneal stromal cells are capable of retaining their plasticity. In fact, they are capable of numerous differentiation cycles. By adopting different cell-based co-culture approaches, we have established that it is possible to de-differentiate activated corneal stromal cells that are fibroblastic in phenotype toward a native uninjured (keratocyte) cell type in terms of cell behavior and biological properties. We have then demonstrated that the cells can be re-activated to the fibroblastic cell phenotype after exposure to exogenous TGF-β1.

TGF-β1 is a known chemotactic agent and mitogen for fibroblastic cells secreted by almost all nucleated cells35 that initiates wound contraction in vivo.6,24 TGF-β1 induces fibroblastic and myofibroblastic differentiation by stimulating cell stratification and matrix component production, while increasing fibrotic protein marker expression36 such as α-SMA, which was confirmed by immunohistochemical data. The action of TGF-β1 was very potent in that it blocked epithelial cell proliferation (data not shown) while stimulating the proliferation and re-activation of the stromal cells. TGF-β1 stimulation superseded the previous effect that co-culturing had on the stromal cell inactivation and keratocyte differentiation and caused the quiescent, noncontractile cells which had previously shown positive expression for keratocan, ALDH3, and lumican to become highly contractile and fibroblastic in their behavior and phenotype. In fact, keratocyte marker expression was lost and replaced by positive expression of Thy-1, α-SMA, and vimentin.

Our findings suggest that corneal stromal cells are able to differentiate numerous times while in culture and that their transition and response is heavily dependent on the niche environment. Since the corneal is avascular, it is the overlying epithelium that is pivotal to stromal cell differentiation. It is, therefore, assumed that it is possible for keratocyte de-differentiation to occur once TGF-β1 supplementation is removed and the “epithelium” is restored.

Investigation and exploration of the plasticity of stromal cells is valuable to corneal tissue engineering with its benefits being threefold: First, it allows for large numbers of corneal stromal cells to be grown quickly and easily in serum-containing media; second, the ability to inactivate expanded, activated fibroblastic cells to a keratocyte linage is important in aiding our understanding of corneal wound-healing mechanisms and the importance of cellular interactions during these processes; and finally, it allows us to engineer corneal tissues that more closely mimic the native cornea, with cells that are in a healthy, inactivated state which may have the potential to act as an important tool with regard to toxicity testing of drugs and irritants, which could, in turn, improve the development of new and improved ocular drugs to treat corneal disease and/or injury.

Conclusion

In this article, we have demonstrated four key elements of corneal cell population behavior in a 3D in vitro model: (i) Epithelial–stromal cellular interactions are reciprocal and bi-directional in manner; (ii) corneal stromal cells require the presence of the epithelia for the in vitro restoration of the inactivated keratocyte phenotype; (iii) corneal stromal cells retain their plasticity in collagen hydrogel environments; and (iv) the mechanical properties of the cornea are defined by epithelial–stromal interactions.

Acknowledgment

Funding from the EPSRC Doctoral Training Center (DTC) in Regenerative Medicine (Grant number EP/F/500491/1) is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Wilson S.E., Liu J.J., and Mohan R.R.Stromal-epithelial interactions in the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res 18,293, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du Y., SundarRaj N., Funderburgh M.L., Harvey S.A., Birk D.E., and Funderburgh J.L.Secretion and organization of a cornea-like tissue in vitro by stem cells from human corneal stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48,5038, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espana E.M., Kawakita T., Di Pascuale M.A., Li W., Yeh L.K., Parel J.M., et al. The heterogeneous murine corneal stromal cell populations in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46,4528, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson S.E., Netto M., and Ambrósio R., Jr., Corneal cells: chatty in development, homeostasis, wound healing, and disease. Am J Ophthalmol 136,530, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuft S.J., Gartry D.S., Rawe I.M., and Meek K.M.Photorefractive keratectomy—implications of corneal wound-healing. Br J Ophthalmol 77,243, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K., Kurosaka D., Yoshino M., Oshima T., and Kurosaka H.Injured corneal epithelial cells promote myodifferentiation of corneal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43,2603, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fini M.E., and Stramer B.M.How the cornea heals: cornea-specific repair mechanisms affecting surgical outcomes. Cornea 24,2, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jester J.V., and Jin H.C.Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractility and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp Eye Res 77,581, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musselmann K., Alexandrou B., Kane B., and Hassell J.R.Maintenance of the keratocyte phenotype during cell proliferation stimulated by insulin. J Biol Chem 280,32634, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura T., Toda S., Mitsumoto T., Oono S., and Sugihara H.Effects of hepatocyte growth factor, transforming growth factor-beta 1 and epidermal growth factor on bovine corneal epithelial cells under epithelial-keratocyte interaction in reconstruction culture. Exp Eye Res 66,105, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayhaw-Barker P.Corneal wound healing: I. The players. Int Contact Lens Clin 22,105, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahearne M., Yang Y., Then K.Y., and Liu K.K.Non-destructive mechanical characterisation of UVA/riboflavin crosslinked collagen hydrogels. Br J Ophthalmol 92,268, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y., Dubois A., Qin X.P., Li J., El Haj A.J., and Wang R.K.Investigation of optical coherence tomography as an imaging modality in tissue engineering. Phys Med Biol 51,1649, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson S.L., Wimpenny I., Ahearne M., Rauz S., El Haj A.J., and Yang Y.Chemical and topographical effects on cell differentiation and matrix elasticity in a corneal stromal layer model. Adv Funct Mater 22,3641, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahearne M., Yang Y., El Haj A.J., Then K.Y., and Liu K.K.Characterizing the viscoelastic properties of thin hydrogel-based constructs for tissue engineering applications. J R Soc Interface 2,455, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahearne M., Wilson S.L., Liu K.K., Rauz S., El Haj A.J., and Yang Y.Influence of cell and collagen concentration on the cell-matrix mechanical relationship in a corneal stroma wound healing model. Exp Eye Res 91,584, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ju B.F., and Liu K.K.Characterizing viscoelastic properties of thin elastomeric membrane. Mech Mater 34,485, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu K.K., and Ju B.F.A novel technique for mechanical characterization of thin elastomeric membrane. J Phys D-Appl Phys 34,91, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mi S., Chen B., Wright B., and Connon C.J.Ex vivo construction of an artificial ocular surface by combination of corneal limbal epithelial cells and a compressed collagen scaffold containing keratocytes. Tissue Eng Part A 16,2091, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pang K., Du L., and Wu X.A rabbit anterior cornea replacement derived from acellular porcine cornea matrix, epithelial cells and keratocytes. Biomaterials 31,7257, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu L., Reinach P.S., and Kao W.W.Y.Corneal epithelial wound healing. Exp Biol Med 226,653, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pei Y., Reins R.Y., and McDermott A.M.Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) 3A1 expression by the human keratocyte and its repair phenotypes. Exp Eye Res 83,1063, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berryhill B.L., Kader R., Kane B., Birk D.E., Teng J., and Hassell A.R.Partial restoration of the keratocyte phenotype to bovine keratocytes made fibroblastic by serum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43,3416, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim A., Zhou C., Lakshman N., and Petrol W.M.Corneal stromal cells use both high- and low-contractility migration mechanisms in 3-D collagen matrices. Exp Cell Res 318,741, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K., Saito J., Yanai R., Yamada N., Chikama T., Seki K., et al. Cell-matrix, and cell-cell interactions during corneal epithelial wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res 22,113, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal V.B., and Tsai R.J.F.Corneal epithelial wound healing. Indian J Ophthalmol 51,5, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson S.L., El Haj A.J., and Yang Y.Control of scar tissue formation in the cornea: strategies in clinical and corneal tissue engineering. J Funct Biomater 3,642, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandrasekher G., and Bazan H.E.P.Corneal epithelial wound healing increases the expression but not long lasting activation of the p85 alpha subunit of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Curr Eye Res 18,168, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyu J., Lee K.S., and Joo C.K.Transactivation of EGFR mediates insulin-stimulated ERK1/2 activation and enhanced cell migration in human corneal epithelial cells. Mol Vis 12,1403, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y., Liou G.I., Gulati A.K., and Akhtar R.A.Expression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase during EGF-stimulated wound repair in rabbit corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 40,2819, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Islam M., and Akhtar R.A.Upregulation of phospholipase C gamma 1 activity during EGF-induced proliferation of corneal epithelial cells: effect of phosphoinositide-3 kinase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42,1472, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kakazu A., Chandrasekher G., and Bazan H.E.P.HGF protects corneal epithelial cells from apoptosis by the PI-3K/Akt-1/bad- but not the ERK1/2-mediated signaling pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45,3485, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dayhaw-Barker P.Corneal wound healing: II. The process. Int Contact Lens Clin 22,110, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 34.West-Mays J.A., and Dwivedi D.J.The keratocyte: corneal stromal cell with variable repair phenotypes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38,1625, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imanishi J., Kamiyama K., Iguchi I., Kita M., Sotozono C., and Kinoshita S.Growth factors: importance in wound healing and maintenance of transparency of the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res 19,113, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karamichos D., Hutcheon A.E.K., and Zieske J.D.Transforming growth factor-beta 3 regulates assembly of a non-fibrotic matrix in a 3D corneal model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 5,228, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]