Abstract

Leiodermatolide is a structurally unique macrolide, isolated from the deep-water marine sponge Leiodermatium sp., which exhibits potent antiproliferative activity against a range of human cancer cell lines (IC50 <10 nM) and dramatic effects on spindle formation in mitotic cells. Its unprecedented polyketide skeleton and stereochemistry were established using a combination of experimental and computational (DP4) NMR methods, and molecular modelling.

Keywords: natural products, antitumour, antimitotic, marine macrolides, NMR spectroscopy, structure elucidation

Marine macrolides that selectively disrupt cell cycle events continue to occupy a central position as lead compounds in the ongoing search for novel anticancer agents,[1-2] highlighted by the recent FDA approval of Halaven® (eribulin mesylate, a fully synthetic analogue of the halichondrins) for the treatment of advanced breast cancer.[3] Lithistid sponges have proven to be a particularly fertile source[4] of such biologically relevant polyketide metabolites, including dictyostatin[5] and discodermolide.[5d,6] As part of a continued program aimed at the discovery of novel bioactive natural products from deep-water marine invertebrates, we have examined the relatively unexplored[7] lithistid sponge Leiodermatium. A crude extract of Leiodermatium sp. was found to exhibit substantial activity in an assay which identifies antimitotic agents through detection of phosphonucleolin, a marker of mitosis.[8] Bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of leiodermatolide (1, Figure 1), whose unprecedented 16-membered macrolide skeleton, featuring an unsaturated side chain terminating in a δ-lactone, has been elucidated through a combination of extensive NMR spectroscopic analysis, comparative DFT GIAO NMR shift calculations and molecular modelling. Leiodermatolide was found to exhibit potent and selective antimitotic activity (IC50 <10 nM) against a range of human cancer cell lines by inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest, and represents a promising new lead for anticancer drug discovery.

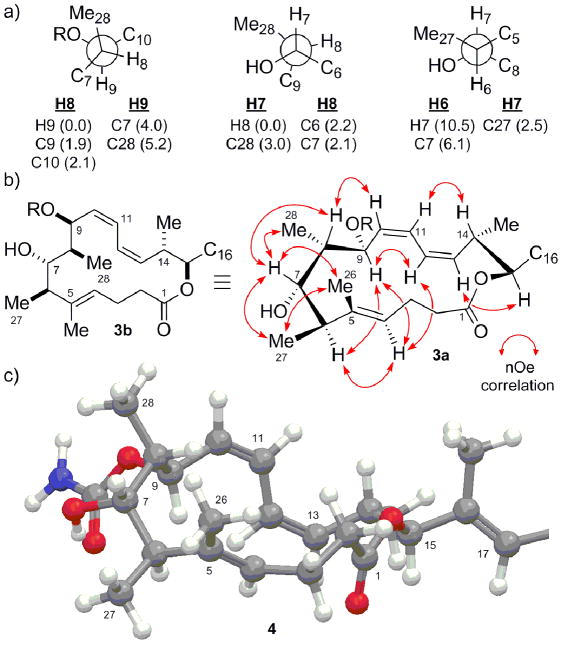

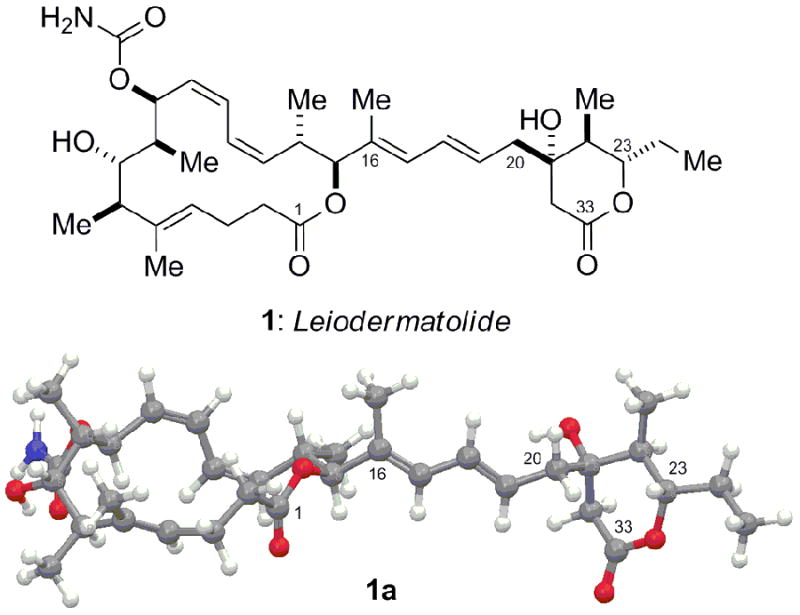

Figure 1.

Structure of leiodermatolide (1) and energy-minimised conformation (1a) - the absolute configurations of the C1–C16 macrolactone and C20–C33 δ-lactone regions are arbitrarily assigned.

A specimen of Leiodermatium (1.04 kg) was collected at a depth of 401 m off the coast of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, using the Johnson-Sea-Link submersible. The frozen sponge was exhaustively extracted using a mixture of EtOAc:EtOH (9:1) followed by partitioning of the dried extract residue between EtOAc and H2O. Vacuum column chromatography of the organic partition on a silica gel stationary phase followed by reverse phase HPLC of the active fraction led to the isolation of leiodermatolide (11.8 mg, 0.0011% wet weight) as an amorphous white powder with −84.2 (c 0.34, MeOH).[9]

HRDART MS analysis of leiodermatolide (1) provided a [M+H]+ ion at m/z 602.3705, appropriate for a molecular formula of C34H51NO8 (calcd for [M+H], 602.3693, Δ = 1.2 mmu), requiring 10 sites of unsaturation.[10] Optimum NMR signal dispersion was realised in CD2Cl2; inspection of the 13C spectrum revealed a total of 34 resonances in agreement with the HRMS formula. 13C NMR resonances attributable to two ester groups (δC 172.4, 170.4), one carbamate (δC 157.6) and 10 olefinic carbons (δC 137.5, 125.9, 128.8, 126.4, 124.7, 137.9, 134.2, 130.0, 131.8, 128.5), accounted for eight of the 10 sites of unsaturation, suggesting the presence of two rings.

Interpretation of the 2D DQF-COSY spectrum coupled with the edited g-HSQC spectrum led to the assignment of seven isolated spin systems (A-G, Figure 2). These spin systems and their connectivity with the remaining atoms enabled assembly into the final planar structure 1b based upon analysis of 2J and 3J 1H-13C couplings observed in the g-HMBC spectrum.[10] Accordingly, HMBC correlations between a methyl resonance (δH 1.39 s, H26) and carbons C4, C5 and C6 served to place it on C5 as well as link spin systems A and B through C5. This assignment was supported by further correlations from H4 to C6 / C26, and H6 to C4 / C5 / C26. Further correlations between H2ab and H3ab with the ester carbon observed at δC 172.4 allowed for C1 to be incorporated into the molecular structure, which could be linked to H15 and thus spin system D through an HMBC correlation from H15 to C1.

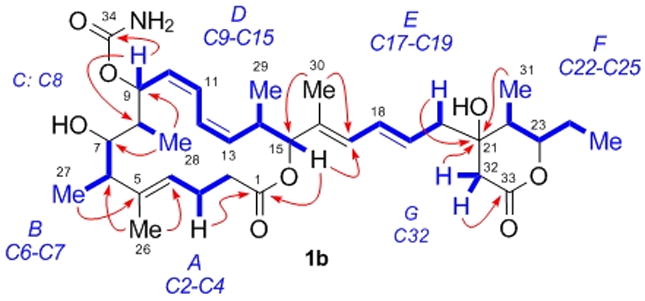

Figure 2.

Isolated 1H spin systems (blue) and 2,3JH,C HMBC NMR correlations (red) leading to the planar structure 1b of leiodermatolide.

Unification of spin systems B, C and D was initially hampered by the lack of scalar coupling between H8 and either H7 or H9, although this observation was subsequently exploited for purposes of stereochemical determination (vide supra). Spin system C thus appeared as an isolated, mutually coupled CHCH3 system [δH 1.72 (br q, 3J = 7.2 Hz) and 1.05 (d, 3J = 7.2 Hz)]. Ultimately, HMBC correlations between H28 and both C9 and C7 clearly placed C8 between these two atoms, supported by correlations from H9 to C7 and H7 to C9 / C28. A carbamate was attached to C9 to account for its chemical shift (δC 68.0), based on an HMBC correlation from H9 to C34 (δC 157.6). The oxygenation implied by the chemical shift of C7 (δC 78.4) was confirmed by acetylation whereby the H7 resonance shifted from δH 3.24 to 4.88.[10] Analysis of the DQF-COSY spectrum was then sufficient to define spin system D containing H15, already related to A, thus completing the 16-membered macrocyclic core of leiodermatolide.

Correlations in the HMBC spectrum between a methyl resonance (δH 1.76, s, H30) and carbons C15, C16 and C17 served to place it on the olefinic carbon C16 as well as link spin systems D and E through C16. This assignment was supported by correlations from H15 to C17 / C30, H17 to C15 / C30 and H18 to C16. The final spin systems F and G could then be connected to E through the quaternary carbon observed at δC 72.3 (C21), whose chemical shift could be accounted for by oxygenation. HMBC correlations from C21 to H19 / H20ab / H31 linked E to F, while correlations from H32ab to C21 as well as to C20 and C22 then established the C21-C32 bond. HMBC correlations from H32ab to the carbonyl carbon observed at δC 170.4 (C33) allowed for incorporation of the second ester carbon into the structure, which could be connected as a δ-lactone onto C23 on the basis of a weak HMBC correlation from H23 to C33, accounting for the remaining site of unsaturation.

Leiodermatolide thus features a 16-membered macrolactone ring with an unsaturated side chain terminating in a δ-lactone ring, which together incorporate five alkenes and nine stereocentres, including a carbamate at C9 and two hydroxyls at C7 and C21. The stereochemistry is segregated into two distinct C1–C16 macrocyclic and C20–C33 δ-lactone clusters, whose spatial isolation means that NMR methods alone are insufficient to unambigously define their relative stereochemistry, which must likely await future synthetic studies.

Determination of stereochemistry within the macrolide core utilised a combination of homo-(3JH,H) and heteronuclear (2,3JC,H)[11] J-based configurational analysis[12] and extensive nOe evidence. Figure 3 depicts the results of NMR experiments for the C9–C17 segment of leiodermatolide. Coupling constant analysis suggested H14 and H15 should be antiperiplanar, which together with nOe contacts between H14 / H29 and H30 suggested the arrangement shown in Figure 3a. Two series of strong nOe enhancements could then be traced along either edge of what was deduced to be a pseudo-planar C9–C17 backbone sequence, as shown in 2 (Figure 3b). The nOe contacts from H10 to H11 and H12 to H13 together with the 10.3 and 11.4 Hz coupling of the respective olefinic protons indicated the Δ-10 and Δ-12 double bonds should be Z-configured, while the nOe correlation from H15 to H17 suggested the Δ-16 trisubstituted olefin to be E-configured. Key nOe enhancements from H9 to H12 and H11 to H14 indicated an S-trans arrangement about C11–C12, where A(1,3)-strain would be minimised by H9 and H14 eclipsing the C10–C11 and C12–C13 olefins respectively. Together with the nOe observed for H14 to H30, this preferred conformation has important implications for assigning the relative configuration of the C6–C9 and C14–C15 stereoclusters; the C8 chain and C15 oxygenation must reside on the same face of the pseudo-planar C9–C17 system such that the macrocycle may be closed. As such, an (S*) configuration at C9 would translate into an (S*,S*) configuration at C14, C15.

Figure 3.

NMR analysis for the C9–C17 spine of leiodermatolide; (a) rotamer and anti-configuration determined for C14–C15, 3JH,H and 2,3JH,C (Hz) in parentheses; (b) key nOe contacts for C9–C17.

Having established the relative configuration between the C14, C15 and C9 stereocentres, attention was turned to assignment of the C6–C9 stereotetrad. As indicated above, vicinal 1H-1H coupling constant analysis revealed 3J(H7,H8) and 3J(H8,H9) to approximate to 0 Hz, suggesting the corresponding torsion angles should approach 90°. Heteronuclear J-based configurational analysis[12] was then used to determine the corresponding rotamers shown in Figure 4a, where an HSQMBC NMR experiment proved crucial to extracting necessary data the HSQC-HECADE experiment failed to provide due to the lack of scalar 1H coupling.[11] The relatively large coupling between H9 and C28 and small coupling between H8 and C9 supported a gauche relationship between the adjacent methyl and carbamate substituents and an anti relationship between C7 and C10. The small values for both 2J(H8,C7) and 3J(H7,C28) indicated the mutually gauche arrangement shown. In the absence of an nOe contact between H6 and H7, the large vicinal coupling constant (3J(H6,H7) = 10.3 Hz) indicated an antiperiplanar relationship.

Figure 4.

Configurational analysis for the C1–C16 macrocyclic region of leiodermatolide; (a) rotamers determined for C5–C10, 3JH,H and 2,3JH,C (Hz) in parentheses; (b) selected key nOe contacts for the C1–C16 macrolactone region; (c) energy-minimised conformer 4 for stereostructure 3b.[14,15]

A series of nOe experiments were then carried out for the C4 to C9 sequence (3a, Figure 4b), which served to define the exact rotamer for C5–C8 and consolidate the foregoing configurational analysis. A strong nOe enhancement between H4 and H6 indicated the Δ-4 double bond should be E-configured. The absence of nOe contacts between H27 and H28 suggested they should be 1,3-anti configured such that syn-pentane-type interactions in the macrocycle would be avoided.[13] Particularly diagnostic nOe’s were observed from H6 to H9 and H7 to H8, while only a weak enhancement was observed from H8 to H9, and none for H7 to H9, which together suggested that H6 / H9 and H7 / H8 should reside on opposite faces of the C6–C9 system. Further nOe enhancements from H8 to H10, H7 to H26 related the orientation of this sequence to the adjacent double bonds, which was reinforced by additional transannular nOe contacts from H4 to H9 and H12.

The combination of this data, the preferred conformation of the C9–C17 backbone derived in Figure 3 and the rotameric restrictions implied by the J-based analysis for the C5–C10 sequence provided truncated macrocycle 3b as the sole stereochemical assignment consistent with the observed NMR data. Notably, this arrangement allows for a hydrogen-bonding interaction between the C7 hydroxyl and C9 carbamate moieties, in agreement with the observed sharpening of 1H resonances for the corresponding C7 acetate derivative.[10]

Molecular modelling[14] provided the energy-minimised conformer 4 (Figure 4c) for the macrolactone structure 3b,[15] which appears wholly consistent with the experimental NMR data (J-values and nOe contacts). Notably, none of the higher energy conformers within 10 kJ.mol-1 exhibited significant conformational variation about the macrolactone region (only minor flexibility in the C2–C3 region), thus supporting the validity of the nOe analysis. Similar modelling of other configurational permutations revealed in each case one or more diagnostic discrepancies with the NMR data.[16]

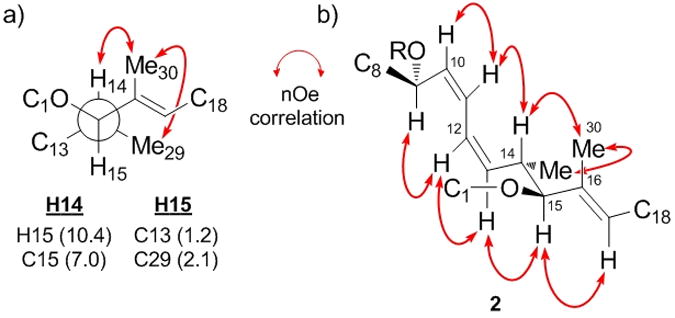

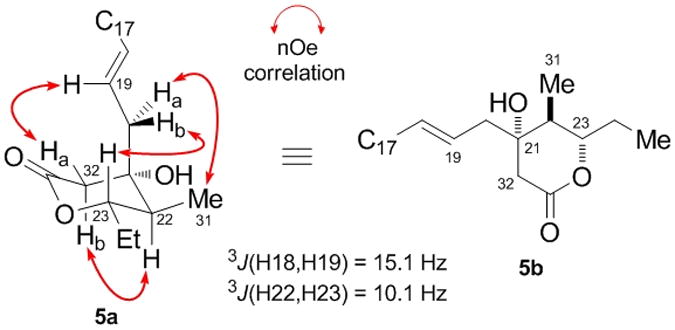

Figure 5 depicts the C17–C33 side-chain stereocluster of leiodermatolide, incorporating the δ-lactone ring. Vicinal 1H-1H coupling constant analysis indicated the Δ-18 olefin to be E-configured (3J(H18,H19) = 15.1 Hz), while H22 and H23 should adopt a diaxial relationship (3J(H22,H23) = 10.1 Hz). A series of nOe experiments again proved important in determining stereochemical relationships. In this case, an nOe contact from H23 to H20b correlated with further contacts for the olefinic H19 proton with H32a, and H20a with H31 to indicate the pseudo-axial nature of the appended C20 side-chain. This was reinforced by an nOe observed between H22 and H32b, indicative of their 1,3-diaxial relationship. These data were supportive of a preferred chair-type conformation 5a and provided the relative δ-lactone stereostructure shown in 5b.

Figure 5.

NMR analysis for the C17–C33 δ-lactone region of leiodermatolide, showing selected key nOe contacts.

With a convincing stereochemical assignment for the 16-membered macrolactone and δ-lactone regions of leiodermatolide reached by NMR spectroscopic analysis, we sought to further reinforce our findings by computational methods. Using the recently developed DP4 NMR prediction methodology of Smith and Goodman,[17a] computational DFT GIAO NMR shift comparisons of experimentally measured 1H and 13C NMR resonances for leiodermatolide and those calculated for the 32 possible macrocyclic and four possible δ-lactone diastereomers in isolation were carried out.[10] This analysis independently predicted a single diastereomer with >99% probability for the macrocyclic region, with the remaining 31 stereochemical permutations being of negligible probability. Reassuringly, the predicted (6R*,7S*,8S*,9S*,14S*,15S*) diastereomer proved to be an exact match for that determined by our NMR analysis (3b, Figure 4b). The same DP4 computational 1H and 13C NMR analysis also suggested the δ-lactone stereocluster 5b (21S*,22S*,23S*), as determined in Figure 5, to be that for leiodermatolide with >99% probability. Notably, this is the first application of the DP4 method to predict the stereochemistry of a complex macrolide from analysis of experimental and calculated NMR shift data.

The relative configurations within the macrolactone (C1–C16) and δ-lactone (C20–C33) stereoclusters had thus been determined as that shown in 1 (Figure 1), where the relationship between these regions is arbitrarily assigned. In order to reduce the remaining stereochemical permutations, we attempted to define the absolute configuration of the macrolide core through preparation and 1H NMR analysis of the corresponding C7–OH (R)- and (S)-MTPA ester derivatives.[18] Whilst two distinct bis-Mosher ester derivatives were able to be prepared, NMR analysis proved inconclusive, with irregular ΔδSR values measured either side of the C7 stereocentre.[10] Surprisingly, esterification occurred initially at C21, indicative of a highly sterically congested environment about C7, which seems likely to underlie the failure of the Mosher ester analysis itself.[19] Determination of the full configuration will thus likely rely on the stereocontrolled synthesis of both possible diastereomers, followed by detailed NMR and chiroptical comparisons with the natural product.

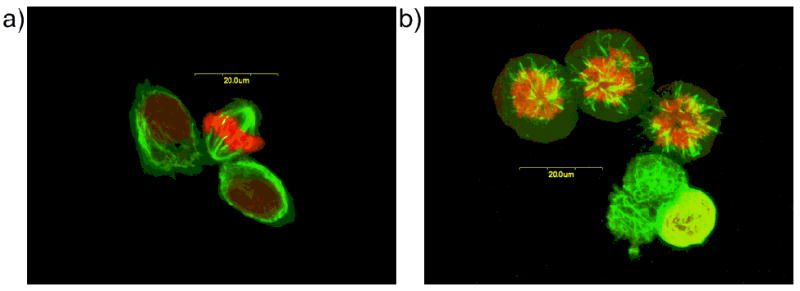

Leiodermatolide exhibited potent antimitotic activity, and strongly inhibited in vitro cell proliferation in several cancer cell lines, including the human A549 lung adenocarcinoma, PANC-1 pancreatic carcinoma, DLD-1 colorectal carcinoma and NCI/ADR-Res ovarian adenocarcinoma, and P388 murine leukaemia, with IC50 values of 3.3 nM, 5.0 nM, 8.3 nM, 233 nM and 3.3 nM respectively. Significantly reduced antiproliferative effects against the Vero monkey kidney cell line (IC50 211 nM) suggest that leiodermatolide may also possess useful selectivity for cancer cells. Cell cycle analysis in the A549 and PANC-1 cell lines confirmed that cell cycle arrest occurred at the G2/M transition.[10] Given that many compounds that induce G2/M cell cycle arrest do so through interaction with the cytoskeletal protein tubulin, the effects on microtubule structure were examined using confocal microscopy. Whilst leiodermatolide proved to have minimal effects on interphase cells, dramatic effects were observed on spindle formation in mitotic cells at concentrations as low as 10 nM (Figure 6). However, leiodermatolide neither induced nor inhibited assembly of purified tubulin in vitro. Thus, whilst the exact mechanism of action presently remains undefined, it is clearly distinct from that of other important antimitotic agents such as the epothilones, discodermolide, taxanes and Vinca alkaloids.[2,20,21]

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence images of PANC-1 cells stained with anti-α-tubulin (green) and propidium iodide (red) and observed with confocal microscopy. Cells were exposed to methanol (control) or 10 nM leiodermatolide; a) Control cells display normal mitotic spindles; b) Leiodermatolide treated cells show abnormal spindle formation.

In summary, leiodermatolide (1) is a structurally unique polyketide-derived macrolide isolated from the deep-water marine sponge Leiodermatium sp., whose potentially novel mode of antimitotic action makes it an exciting new lead for anticancer drug discovery. Its scarce natural abundance also makes it a prime target for realising a practical synthesis. Studies towards this end, including resolution of the remaining configurational issues, will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the NIH (CA-93455), the State of Florida Center of Excellence in Biomedical and Marine Biotechnology (funding of expedition), EPSRC (EP/F025734/1) and Clare College, Cambridge (Fellowship to S.M.D.). We thank Dr. S. Smith (Cambridge) for assistance with NMR prediction studies, Dr. R. Britton (SFU, Canada) for helpful discussions and Dr. M. Frey, Dr. A. Khrishnaswami (JEOL USA) and Dr. P. Grice (Cambridge) for assistance with NMR method optimisation.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Ian Paterson, Email: ip100@cam.ac.uk.

Dr. Amy E. Wright, Email: awrigh33@hboi.fau.edu.

References

- 1.a) Dalby SM, Paterson I. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2010;13:777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Butler MS. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:475. doi: 10.1039/b514294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Newman DJ, Cragg GM. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:461. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Paterson I, Anderson EA. Science. 2005;310:451. doi: 10.1126/science.1116364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yeung K-S, Paterson I. Angew Chem. 2002;114:4826. doi: 10.1002/anie.200290057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:4632. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Cragg GML, Kingston DGI, Newman DJ. Anticancer Agents From Natural Products. Taylor & Francis Group; Boca Raton: 2005. [Google Scholar]; b) Altmann KH, Gertsch J. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:327. doi: 10.1039/b515619j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Ledford H. Nature. 2010;468:608. doi: 10.1038/468608a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm233863.htm.

- 4.Wright AE. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21:801. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Pettit GR, Cichacz ZA, Goa F, Boyd MR, Schmidt JM. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. 1994:1111. [Google Scholar]; b) Isbrucker RA, Cummins J, Pomponi SA, Longley RE, Wright AE. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:75. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Paterson I, Britton R, Delgado O, Wright AE. Chem Commun. 2004:632. doi: 10.1039/b316390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Florence GJ, Gardner NM, Paterson I. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:342. doi: 10.1039/b705661n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ter Haar E, Kowalski RJ, Hamel E, Lin CM, Longley RE, Gunasekera SP, Rosenkranz HS, Day BW. Biochemistry. 1996;35:243. doi: 10.1021/bi9515127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.To date, only two secondary metabolites, leiodolides A and B, have been reported from Leiodermatium, which show moderate cytotoxicity in a panel of tumour cell lines: Sandler JS, Colin PL, Kelly M, Fenical W. J Org Chem. 2006;71:7245. doi: 10.1021/jo060958y.

- 8.Stockwell BR, Haggarty SJ, Schreiber SL. Chem Biol. 1999;6:71. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attempts to generate suitably crystalline material or derivatives for X-ray crystallographic analysis have thus far proven unsuccessful.

- 10.See supporting information for further details.

- 11.Heteronuclear coupling constants were extracted from a combination of HSQC-HECADE and G-BIRDR-HSQMBC NMR experiments: Marquez BL, Gerwick WH, Williamson RT. Magn Reson Chem. 2001;39:499.. See supporting information for further details.

- 12.Matsumori N, Kaneno D, Murata M, Nakamura H, Tachibana K. J Org Chem. 1999;64:866. doi: 10.1021/jo981810k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann RW. Angew Chem. 2000;112:2134. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:2054. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macromodel (Version 9.7), 10,000 step Monte Carlo search performed with the MMFFs force field using a CHCl3 solvent model: Mohamadi F, Richards NGJ, Guida WC, Liskamp R, Lipton M, Caufield C, Chang G, Hendrickson T, Still WC. J Comput Chem. 1990;11:440.

- 15.Modelling was carried out for both δ-lactone diastereomers of 1, whose lowest energy conformers exhibited identical macrolactone regions: see supporting information for further details.

- 16.Particular inconsistencies included syn-pentane interactions between H27 and H28, or no possibility of the nOe contact observed between H6 and H9.

- 17.Smith SG, Goodman JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12946. doi: 10.1021/ja105035r.; See also: Smith SG, Goodman JM. J Org Chem. 2009;74:4597. doi: 10.1021/jo900408d.; Smith SG, Channon JA, Paterson I, Goodman JM. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:6437.

- 18.Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4092. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steric crowding may cause the conformation of the ester to deviate significantly from that assumed by the advanced Mosher model: Ohtani I, Kusumi T, Kashman Y, Kakisawa H. J Org Chem. 1991;56:1296.

- 20.Buey RM, Barasoain I, Jackson E, Meyer A, Giannakakou P, Paterson I, Mooberry S, Andreu JM, Diaz JF. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1269. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detailed biological studies will be reported elsewhere.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.