Abstract

Objective

The expanding overweight and obesity epidemic notwithstanding, little is known about their long-term effect on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The main objective of this study was to investigate whether overweight (body mass index [BMI] 25–<30 kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) young adults have poorer HRQoL 20 years later.

Methods

The authors studied 3014 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, a longitudinal, community-dwelling, biracial cohort from four cities. BMI was measured at baseline and 20 years later. HRQoL was assessed via the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey at year 20. Higher PCS or MCS scores indicate better HRQoL.

Results

Mean year 20 PCS score was 52.2 for normal weight participants at baseline, 50.3 for overweight, and 46.4 for obese (P-trend <0.001). This relation persisted after adjustment for baseline demographics, general health, and physical and behavioral risk factors and after further adjustment for 20-year changes in risk factors. No association was observed for MCS scores (P-trend 0.43).

Conclusion

Overweight and obesity in early adulthood are adversely associated with self-reported physical HRQoL, but not mental HRQoL 20 years later.

Introduction

Approximately 65% of the U.S. population is overweight (body mass index [BMI] 25- < 30 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). (1) Overweight and obesity have increased at staggering rates in the U.S. over the last 20 years and continue to rise. (2, 3) These increases are a public health concern because having a BMI in the overweight or obese range is associated with an increased risk of developing, among others, hypertension, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, and coronary artery disease. (4, 5) Obesity currently accounts for over 100,000 excess deaths (6) and 5–7% of annual medical spending in the U.S. (7)

Patient-centered and patient-reported measures of health status have become increasingly important in our current efforts to assess the health of individuals and populations. (8) Given the current overweight and obesity epidemic, it is important to determine the impact of overweight/obesity on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which is the effect of medical condition(s) on an individual’s subjective well-being, and physical, mental, and social functioning. (9) A small number of longitudinal studies have linked overweight and obesity to worse perceived health, impaired mobility, and greater disability compared to normal weight. (10–12) These studies primarily assessed self-reported aspects of physical HRQoL in middle-aged and older individuals (10–12) or in samples of participants with a wide range of ages. (11)

To our knowledge, no study has investigated whether overweight and obesity in young adulthood is comprehensively associated with poor HRQoL (i.e., self-reported mental health, social functioning, and physical functioning) as early as middle age. Using data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, we examined the relationship of overweight and obesity in young adulthood with subsequent physical, mental, and social HRQoL after 20 years of follow-up for the whole cohort and among specific race-sex groups. Further, we investigated the association of changes in weight with physical, mental, and social HRQoL among the whole cohort.

Methods

Participants

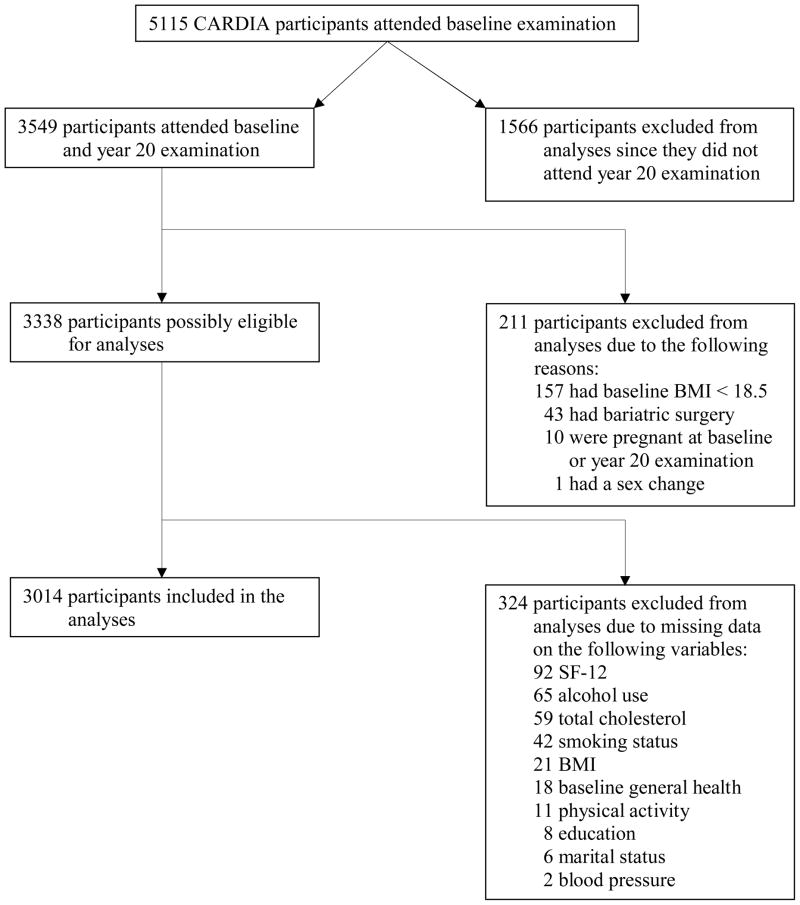

CARDIA is an NHLBI-sponsored, longitudinal multi-center investigation of cardiovascular risk development in 5115 white and African-American men and women from Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California. A detailed description has been provided elsewhere. (13) The study was designed to include approximately equal numbers of participants by: sex, race (black/white), education (high school or less vs. more than high school), and age (18–24 years/25–30 years). The current study includes data from the baseline (1985–86) and year 20 (2005–06) examinations. The final cohort for analysis included 3014 participants. Figure 1 displays the number of excluded participants and the reasons for exclusion.

Figure 1.

Number of participants excluded from analyses and reasons for exclusion.

Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life, Body Mass Index, and Risk Factors

HRQoL was assessed during year 20 (2005–06) using the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12), which contains the Physical Component Summary (PCS) score and Mental Component Summary (MCS) score. (14) The PCS score measures physical functioning, bodily pain, general health, and role limitations due to physical problems. The MCS score assesses social functioning, vitality, mental health, and role limitations due to emotional problems. The SF-12 was scored using the standard algorithm, (14) which assumes that the PCS and MCS scores are orthogonal and provides norm-based standardized summary scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. A higher PCS or MCS score denotes better HRQoL. Potential participants were also asked an abbreviated version of the general health question from the SF-12 during the recruitment interview in 1985–86.

Standardized protocols (13) were used to measure height, weight, cholesterol, glucose, blood pressure, smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity at baseline and year 20. Weight and height measurements were taken using a balance beam scale. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.2 lb with paticipants wearing light clothing and body height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm without shoes. BMI was computed as weight divided by height squared (kg/m2). Lipids and lipoproteins were measured in fasting plasma samples and determined by enzymatic procedures using the Abbott Biochromatic Analyzer. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or current use of diabetic medication. After a five minute rest period, three seated blood pressure measurements were obtained in a quiet room during the baseline examination using the Hawksley random-zero sphygmomanometer. An average of the 2nd and 3rd readings was used in the analyses.

Information on demographic characteristics, alcohol use, smoking status, and medication use was collected via interview. Using thresholds set by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, (15) alcohol use was defined as none (no drinks consumed in the past year), moderate (for men, ≤ 14 drinks/week and ≤ 4 drinks on the day they drank the most in the past month; for women, ≤ 7 drinks/week and ≤ 3 drinks on the day they drank the most in the past month), and at-risk (for men, ≥ 15 drinks/week or ≥ 4 drinks on the day they drank the most in the past month; for women, ≥ 8 drinks/week or ≥ 3 drinks on the day they drank the most in the past month). The “at-risk” category suggests an increased risk of developing alcohol-related problems, but does not signify the presence of substance abuse or dependence.

Total physical activity was measured using the interviewer-based CARDIA Physical Activity History questionnaire, which assesses participation in 13 different exercise and sport activity categories over the past 12 months. (16) To obtain a frequency score, participants were asked whether each activity was performed during the past year, along with the number of months and duration of time they participated in the activity. Total physical activity was the sum of intensity and frequency scores, expressed as exercise units.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics between black and white women and men were compared separately using χ2 tests (for categorical variables) or t-tests (for continuous variables). Planned analyses focused on two main outcomes: SF-12 summary scores and SF-12 individual items. The first set of analyses focused on the longitudinal relationship between baseline BMI and year 20 SF-12 summary scores. The second set of analyses involved investigating the longitudinal association between baseline BMI and year 20 SF-12 individual items (i.e., 12 questions). Finally, the third set of analyses focused on determining whether an increase in BMI over time was associated with worse year 20 SF-12 summary scores.

General linear models were used to compute mean SF-12 summary scores at year 20 across baseline BMI groups for the entire cohort and each race-sex group. Linear trend was tested in multivariate models using linear regression for continuous outcomes and logistic regression for binary outcomes. BMI was included as a continuous variable in the multivariate models. When significant differences in summary scores were detected among the entire cohort, individual questions from the SF-12 were analyzed to illustrate the functional meaning of the findings. Six physically oriented questions contribute primarily to the PCS, and six mentally oriented questions contribute primarily to the MCS (i.e., 12 items total). Response categories for each item were dichotomized to indicate favorable or adverse status. For example, “not limited” in climbing several flights of stairs was categorized as favorable vs. “limited a little” or “limited a lot” were categorized as adverse. General linear models (least square estimates) were also used to compute the prevalence (percentage) of favorable and adverse health status for the cohort and for each race-sex group. All analyses were repeated with adjustment for sex and race (black/white) (whole cohort analysis only), and the following baseline variables: age, education (in years), marital status (married, never married, other), cigarette smoking (never, former, current), total physical activity (exercise units), diabetes (yes/no), systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication (yes/no), a single question from the SF-12 assessing general health status (excellent/good/fair/poor), total cholesterol, and alcohol use (none, moderate, at-risk).

Baseline and year 20 BMI groups were cross-tabulated and classified into six BMI change categories: normal-weight at baseline and year 20 (normal-normal); normal-weight at baseline but overweight (normal-overweight) or obese (normal-obese) at year 20; overweight (overweight-overweight) or obese (obese-obese) at both baseline and year 20; and overweight at baseline but obese at year 20 (overweight-obese). Participants who lost weight were not included in this analysis due to a small sample size (n=54). General linear models were used to compute adjusted mean SF-12 summary scores, and comparisons were made between normal-normal weight individuals (referent) and the other 5 BMI change groups by F tests. Comparisons of mean SF-12 summary scores were also made between normal-obese (referent) versus overweight-obese and obese-obese. Analyses were adjusted for baseline covariates described above.

To examine the potential role of cardiovascular risk factor progression on any associations observed between BMI and SF-12 summary scores or individual items, all models were further adjusted for changes over 20 years (year 20 – baseline) for continuous variables (physical activity, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol), year 20 risk factor measurements for categorical variables (education level, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, diabetes, antihypertensive medication, and lipid-lowering medication), and baseline variables (age, physical activity, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, and general health status). Since these additional adjustments did not appreciably alter relationships between BMI and SF-12 summary scores, results are not shown.

Of the 5115 participants at baseline, 2101 were excluded from analyses as described in Figure 1. We adjusted for selection bias (i.e., missing data due to missing information in some covariates and losses to follow-up) using inverse probability weighting (IPW). (17) Specifically, we modeled the probability of dropping out at year 20 separately for each race-sex group and the entire cohort with logistic regressions by treating dropping out as the response variable and baseline covariates as independent variables. We then inversely weighted the complete observation in the regression equations used to study the various associations with the probability that a participant was still in the study. We used the bootstrap method to estimate the variance of the mean SF-12 summary scores computed with the weighted adjustments by drawing 1000 independent samples, each the same size as the original sample. We then estimated the mean SF-12 summary scores for each sample and the confidence intervals from the 1000 samples. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 displays baseline characteristics for the entire cohort and by race-sex group. A higher percentage of black women were overweight (25.9% vs. 15.1%; P <0.001) or obese (20.7% vs. 6.2%; P <0.001) as compared to white women. A higher percentage of black men were obese as compared to white men (9.7% vs. 4.9%; P <0.001). A higher percentage of white women (P <0.001) and white men (P <0.001) engaged in at-risk drinking as compared to black women and black men, respectively. A higher percentage of black men were current smokers compared to white men (P <0.01). As compared to white women, black women on average engaged in lower total physical activity (P <0.001), had higher mean systolic blood pressure (P <0.001), and had higher mean total cholesterol (P <0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 3014 Participants, the CARDIA Study, 1985–86

| Characteristic | Entire cohort (n=3014) | Black Women (n=797) | White Women (n=860) | Black Men (n=557) | White Men (n=800) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (mean) | 25.1 | 24.5a | 25.7a | 24.5b | 25.5b |

| Education (years) | 14.1 | 13.2a | 14.8a | 13.2b | 14.8b |

| Marital Status (%) | |||||

| Married | 24.2 | 22.3a | 29.4a | 19.6 | 23.5 |

| Never married | 67.5 | 66.3a | 61.4a | 72.7 | 71.9 |

| Other | 8.3 | 11.4 | 9.2 | 7.7b | 4.6b |

| Behavioral Factors | |||||

| Current alcohol use (%) | |||||

| None | 12.3 | 20.5a | 7.8a | 13.7b | 8.1b |

| Moderate | 49.8 | 60.5a | 50.8a | 47.7b | 39.6b |

| At-risk | 37.9 | 19.0a | 41.4a | 38.6b | 52.3b |

| Smoking status (%) | |||||

| Never | 60.6 | 63.8a | 56.3a | 58.9 | 63.0 |

| Former | 14.0 | 9.2a | 20.7a | 10.6 | 14.1 |

| Current | 25.4 | 27.0 | 23.0 | 30.5b | 22.9b |

| Total PA (mean units) | 426.1 | 269.2a | 413.2a | 539.0 | 517.7 |

| Physical Factors | |||||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | |||||

| Normal weight (%) | 65.5 | 53.4a | 78.7a | 62.5 | 65.2 |

| Overweight (%) | 24.2 | 25.9a | 15.1a | 27.8 | 29.9 |

| Obese (%) | 10.3 | 20.7a | 6.2a | 9.7b | 4.9b |

| Diabetes (%)c | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg, mean) | 110.2 | 108.2a | 104.8a | 115.5 | 114.4 |

| Antihypertensive medication use (%) | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL, mean) | 177.7 | 180.6a | 176.3a | 177.2 | 176.2 |

Abbreviation: Total PA, total physical activity expressed in exercise units (sum of frequency and intensity scores).

P <.05 for black women versus white women.

P <.05 for black men versus white men.

Diabetes = fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or current use of diabetic medication.

Baseline Body Mass Index and Year 20 SF-12 Summary Scores

Baseline BMI was inversely associated with PCS scores 20 years later for the entire cohort (P-trend <0.001) and each race-sex group (P-trend <0.001 for black and white women, and white men; P-trend 0.03 for black men). For example, mean PCS scores were 52.2, 50.3, and 46.4 for normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals respectively. Results were similar after adjusting for baseline covariates, with the exception of black men for whom findings were not significant (Table 2). After adjusting for 20-year changes in covariates, results remained similar with the exception of white men, who had a marginally significant P-trend (P-trend = 0.07) (data not shown). No relationship was found between BMI and MCS scores among the entire cohort or any race-sex group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted SF-12 Mean Summary Scores after 20 Years of Follow-up (n=3014), the CARDIA Study, 1985–2006a

| Baseline Group (Body mass index in 1985–86) | Mean Physical Component Summary (PCS) Score | Mean Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score |

|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | ||

| Normal weight 18.5 – <25 (n = 1973) | 52.2 | 50.6 |

| Overweight 25 –<30 (n = 730) | 50.3 | 51.0 |

| Obese ≥ 30 (n = 311) | 46.4 | 50.8 |

| P-trend | <0.001 | 0.53 |

| Black women | ||

| Normal weight 18.5 – <25 (n = 446) | 51.2 | 49.3 |

| Overweight 25 –<30 (n = 213) | 48.0 | 50.7 |

| Obese ≥ 30 (n = 176) | 45.1 | 51.0 |

| P-trend | <0.001 | 0.10 |

| White women | ||

| Normal weight 18.5 – <25 (n = 698) | 52.8 | 50.0 |

| Overweight 25 –<30 (n = 137) | 49.1 | 49.7 |

| Obese ≥ 30 (n = 54) | 47.2 | 49.0 |

| P-trend | <0.001 | 0.77 |

| Black men | ||

| Normal weight 18.5 – <25 (n = 359) | 51.1 | 52.1 |

| Overweight 25 –<30 (n = 161) | 49.9 | 51.8 |

| Obese ≥ 30 (n = 57) | 49.4 | 52.7 |

| P-trend | 0.12 | 0.83 |

| White men | ||

| Normal weight 18.5 – <25 (n = 546) | 53.1 | 51.5 |

| Overweight 25 –<30 (n = 241) | 53.1 | 51.3 |

| Obese ≥ 30 (n = 41) | 46.4 | 49.7 |

| P-trend | <0.001 | 0.64 |

Adjusted for baseline covariates: age, education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, total physical activity, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, and general health status. Models with all participants were also adjusted for race and sex.

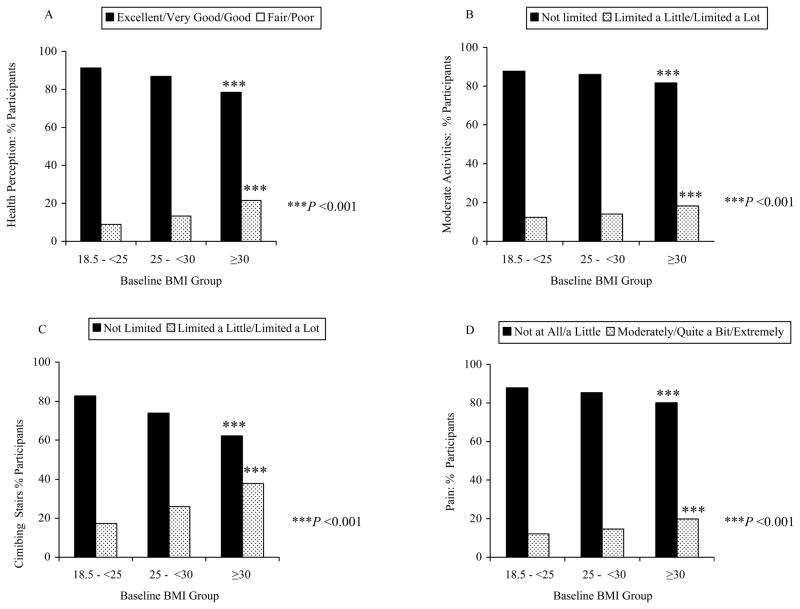

Baseline Body Mass Index and Year 20 Individual SF-12 Items

Figure 2A illustrates the response from the entire cohort to item 1 on the SF-12, “In general, would you say your health is….” after adjustment for baseline covariates. Among the entire cohort, 21.5% of obese participants perceived their health as fair or poor (adverse) compared to 13.2% of overweight participants, and 8.8% of normal weight participants (P-trend <0.001). For the other 5 SF-12 physical health questions, the prevalence of adverse outcomes was lowest for normal-weight participants and higher for those overweight or obese at baseline in both unadjusted analyses (P-trends <0.001) and analyses adjusting for baseline covariates (P-trend range 0.004 - <0.001). Consistent and similarly significant inverse associations were found between increasing weight categories and favorable health status. Figure 2(B–D) show examples of physical health questions that were associated significantly with BMI. After adjusting for 20-year changes in covariates, significant inverse associations remained for all physical health questions (P-trends <0.001) except the moderate activities item (data not shown). Of note, at least 62% of individuals obese at baseline reported favorable status on each of these individual physical HRQoL items 20 years later. On average, these individuals were younger than the obese individuals who reported adverse health status; significant age differences were found for climbing stairs (P <0.01). Data from individual mental health items are not presented since a relationship between MCS score and BMI was not observed.

Figure 2.

Adjusted prevalence of SF-12 favorable and adverse outcomes (individual items/questions) at year 20 by baseline body mass index (BMI) group (n=3014; entire cohort), the CARDIA study, 1985–2006. Outcomes were adjusted for baseline covariates that included race, sex, age, education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, total physical activity, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, and general health status. A=Health perception, B=Moderate activities, C=Climbing several flights of stairs, D=Pain. ***P <0.001

Change in Body Mass Index from baseline to Year 20 and SF-12 Summary Scores

Participants in the obese-obese group had the lowest (worst) mean PCS score of 46.3 and the normal-normal group had the highest mean PCS score of 53.0. These groups were significantly different from each other (P <0.001). PCS scores were significantly lower for participants in the normal-overweight (P <0.05), normal-obese (P <0.001), and overweight-obese (P <0.001) groups, compared to the normal-normal group. The obese-obese group had a significantly lower PCS score compared to the normal-obese group (P <0.001) (data not shown). These differences persisted after adjusting for baseline covariates (Table 3) and 20-year changes in covariates (data not shown). Data from the MCS scores are not presented due to a lack of relationship between BMI and MCS score (data not shown).

Table 3.

Adjusted Mean SF-12 PCS Scores at Year 20 by Body Mass Index (BMI) Category Change after 20 years of Follow-up (n=2960), the CARDIA study, 1985–2006a

| BMI Category Change from Baseline to Year 20 | Mean Physical Component Summary (PCS) Score (95% confidence intervals) |

|---|---|

| Normal - Normal (n = 765) | 52.6 (52.1, 53.1) |

| Normal - Overweight (n = 827) | 51.9 (51.4, 52.5)* |

| Normal - Obese (n = 372) | 50.6 (49.8, 51.3)*** |

| Overweight - Overweight (n = 207) | 51.8 (50.8, 52.9) |

| Overweight - Obese (n = 494) | 49.7 (49.0, 50.3)*** |

| Obese - Obese (n = 295) | 47.8 (46.9, 48.6)*** |

Analysis included data from the entire cohort with the exception of 54 participants who did not increase in weight from baseline to the year 20 examination. Adjusted for race, sex, and baseline age, education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol use, total physical activity, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, total cholesterol, and general health status.

P <0.05,

P <0.01,

P <0.001 for comparison with the Normal-Normal group.

Effect of Nonresponse

We employed an inverse probability weighting method to adjust for the potential bias caused by dropouts. The two sets of estimates (weighted and non-weighted) were consistent, with the direction and magnitude of the relationship between BMI and SF-12 summary scores persisting across most of the sensitivity analyses (data not shown). Therefore, our results were likely robust despite some loss of participants due to dropout or missing data.

Discussion

In this community-based cohort, excess weight in young adulthood was associated with poor self-reported physical, but not mental or social HRQoL two decades later. This relationship was exemplified by an elevated likelihood of limitations in activities, and by the presence of bodily pain. After adjusting for baseline demographics, general health, and physical and behavioral risk factors, this relationship persisted for the entire cohort and three race-sex groups. After further adjustment for 20-year changes in covariates, this relationship was sustained among the entire cohort and black and white women. Further, transitioning into a heavier weight group or maintaining a BMI in the obese range over 20 years were associated with worse physical health functioning.

To our knowledge, the current study was the first to investigate the long-term impact of overweight and obesity on the entire spectrum of HRQoL domains in a sample of initially healthy young adults. Our finding of a longitudinal inverse relationship between a high BMI and low PCS score among the entire cohort and each race-sex group highlights the significant impact that excess body weight in young adulthood can have on physical HRQoL 20 years later, even while individuals are still relatively young (i.e., forties or early fifties). This finding is strong given that it remained for all groups except black men after adjusting for important baseline covariates. The lack of findings in black men may have resulted from low power since the sample size for this group was much smaller than the other three race-sex groups.

A significant relationship between BMI and MCS scores was lacking. Our findings are consistent with results from previous studies that used the SF-12. For example, in a cross-sectional study of 1168 Caucasian and African-American male Veterans, a higher BMI was associated with a lower PCS score but no significant associations with MCS scores were found. (18) In another cross-sectional study of men and women ages 16–64 from Sweden, overweight women and men and obese women had significantly lower PCS scores compared to those in the normal weight group. (19) Of note, it has been suggested that having a higher BMI may be associated with better mental health scores. In a cross-sectional study of over 2500 Canadians, overweight men and class II (BMI = 35 to <40) and III (BMI ≥ 40) obese women had better MCS scores compared to normal weight individuals, but these findings were not significant. (20) In the current study, slightly better MCS scores were found in overweight individuals from the entire cohort and among overweight or obese black women compared to normal weight individuals; however, these differences were not significant. It has been proposed that some individuals may be able to adjust psychologically to a health condition even if deficits in physical functioning remain. Further, it has been suggested that individuals with a high BMI might go through a similar period of psychological adjustment, which could help to explain why excess weight has been found to be associated with better MCS scores. (20, 21) This adjustment could potentially explain the differing findings for MCS scores and PCS scores in our study.

Further, our study showed that a BMI in the obese range over two decades or changing from normal weight at baseline to obese 20 years later were associated with poor physical HRQoL as compared to maintaining a normal weight the entire time. These findings persisted even after adjusting for baseline and 20-year changes in covariates. Although additional studies need to be conducted to replicate these important findings, it appears that young adults can benefit from two vital messages. First, early or long-term exposure to obesity puts one at risk of poor physical HRQoL. Second, maintaining a normal BMI throughout one’s lifetime is important since it is associated with good physical HRQoL.

Finally, an analysis of the SF-12 physical health individual items revealed that individuals in the obese range were significantly more likely to report limitations in moderate activities and climbing several flights of stairs as compared to normal or overweight individuals. In a cross-sectional study of 3605 Spanish individuals who were in the early 70s, obese individuals reported limitations in several types of physical functioning such as vigorous activities, bending/kneeling, and climbing several flights of stairs. (22) Obese women also reported difficulties climbing one flight of stairs, walking, and bathing/dressing themselves. It is noteworthy that the participants in our study were on average 45 years old when HRQoL was measured, which is 25 years younger than individuals in the Spanish study. Yet, on average, many were already experiencing limitations in physical functioning, significantly higher pain, and lower general health compared to their normal weight counterparts. Given the rise in prevalence of obesity in several developed countries, some reassurance might be taken in our finding that a large percentage (62%) of obese individuals reported having excellent, very good, or good general health, no limitations in moderate activities or climbing stairs, and little or no pain interfering with work. However, these percentages were significantly lower compared to normal weight individuals. Further, obese participants who reported no limitations in climbing stairs, or no pain-related work interference were significantly younger than obese individuals who reported difficulties in these areas.

A limitation of this study was that the entire SF-12 was not administered during the baseline examination. Therefore, it was not possible to adjust for baseline HRQoL. However, we adjusted for baseline general health status in all of our analyses, which likely helped to reduce the influence of at least one important baseline aspect of HRQoL. It is unlikely that the participants could have had poor HRQoL at baseline since the CARDIA study cohort comprised healthy young adults ages 18–30 at baseline of whom 98% were able to perform at least one stage of a graded exercise test (nine 2-minute increasingly difficult stages of walking on a treadmill), with an average of 4.1 stages completed.

In closing, we established a strong link between having a high BMI at a young age and poor physical HRQoL two decades later. Further, our findings suggest that poor physical HRQoL may be prevented in midlife if young adults successfully maintain a BMI in the normal range. Good physical HRQoL is an essential component of healthy aging. Raising public awareness of the adverse impact of having an unhealthy weight in young adulthood is important to lessen the future burden of disability and impaired quality of life in the aging population.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Andrea Kozak’s work on this paper was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship in Cardiovascular Epidemiology and Prevention (5-T32-HL069771-04). The work of Cheeling Chan and Drs. Martha Daviglus, Kiang Liu, Catarina Kiefe, and David Jacobs was supported in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC-48047, N01-HC-48048, N01-HC-48049, N01-HC-48050, and N01-HC-95095 (CARDIA Study).

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM. Epidemiologic aspects of overweight and obesity in the United States. Physiol Behav. 2005;86(5):599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8 (suppl):13–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289(1):76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flegal KM, Graubard BI, Williamson DF, Gail MH. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005;293(15):1861–1867. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein E, Ruhm C, Kosa K. Economic causes and consequences of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:239–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medicine Io. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontaine KR, Cheskin LJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life in obese persons seeking treatment. J Fam Pract. 1996;43(3):265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damush TM, Stump TE, Clark DO. Body-mass index and 4-year change in health-related quality of life. J Aging Health. 2002;14(2):195–210. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferraro KF, Su YP, Gretebeck RJ, Black DR, Badylak SF. Body mass index and disability in adulthood: a 20-year panel study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):834–840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Yan LL, Pirzada A, Garside DB, Schiffer L, et al. Body mass index in middle age and health-related quality of life in older age: the Chicago heart association detection project in industry study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2448–2455. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs DR, Jr, Hahn L, Haskell W, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and reliability of short physical activity history: Cardia and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1989;9:448–459. doi: 10.1097/00008483-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robins J, Rotnitzky A, Zhao L. Analysis of semiparametric regression models for repeated outcomes in the presence of missing data. JASA. 1995;90:106–129. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yancy WS, Jr, Olsen MK, Westman EC, Bosworth HB, Edelman D. Relationship between obesity and health-related quality of life in men. Obes Res. 2002;10(10):1057–1064. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life--a Swedish population study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(3):417–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopman WM, Berger C, Joseph L, Barr SI, Gao Y, Prior JC, et al. The association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: Data from CaMos, a stratified population study. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:1595–1603. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer MA, Hopman WM, MacKenzie TA. Physical functioning and mental health in patients with chronic medical conditions. Qual Life Res. 1999;8(8):687–691. doi: 10.1023/a:1008917016998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Garcia E, Banegas Banegas JR, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Perez-Regadera AG, Ganan LD, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Relation between body weight and health-related quality of life among the elderly in Spain. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Jun;27(6):701–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]