Abstract

Although epigenetic aberrations frequently occur in aging and cancer and form a core component of these conditions, perhaps the most useful aspect of epigenetic processes is that they are readily reversible. Unlike genetic effects that also play a role in cancer and aging, epigenetic aberrations can be relatively easily corrected. One of the most widespread approaches to the epigenetic alterations in cancer and aging is dietary control. This can be achieved not only through the quality of the diet, but also through the quantity of calories that are consumed. Many phytochemicals such as sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables and green tea have anticancer epigenetic effects and are also efficacious for preventing or treating the epigenetic aberrations of other age-associated diseases besides cancer. Likewise, the quantity of calories that are consumed have proven to be advantageous in preventing cancer and extending the lifespan through control of epigenetic mediators. The purpose of this chapter is to review some of the most recent advances in the epigenetics of cancer and aging and to provide insights into advances being made with respect to dietary intervention into these biological processes that have vast health implications and high translational potential.

X.1 Introduction

Although there are many different variations of the definition of epigenetics, perhaps the most widespread is that epigenetic processes involve changes that are heritable but are not encoded with the DNA sequence itself. There are numerous types of epigenetic mechanisms and the three most important in mammals include changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs.

DNA methylation is the most studied of the epigenetic processes and is based on the addition of a methyl moiety (CH3) donated enzymatically from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to the 5-positon of cytosine, primarily occurring in CpG dinucleotides. This is carried out by three major methyltransferases (DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B) in mammalian systems. DNMT1 is responsible for maintaining the methylation pattern that is largely preserved with each mitotic division and DNMT3A and DNMT3B are more involved with de novo methylation, the creation of new methylated cytosines (5-methylcytosines) at cytosine that were not previously methylated. In general, the more methylated a gene regulatory region becomes, the less transcription will occur from the promoter although there are notable exceptions to this dogma as occurs with the gene that encodes human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), the key regulatory gene of telomerase (Daniel et al. 2012; Poole et al. 2001).

Epigenetic changes are also mediated by histone modifications. Although histone acetylation and methylation are the most studied of these modifications, others also occur such as histone phosphorylation, ubiquitination, biotinylation, sumoylation and ADP-ribosylation. The number of enzymes that carry out histone modifications is large relative to those that mediate DNA methylation and the two that often attract interest, especially with regard to cancer and aging, are the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and the histone deactylases (HDACs) (Kouzarides 2007). In general, the more acetylated the histone amino tails become, the more likely it is that the gene promoter region that contains those histones will have increased transcriptional activity (Clayton et al. 2006).

Non-coding RNA, the third major type of epigenetic control in mammalian systems, also is important in gene expression. For example, microRNA (miRNA) consists of single-stranded non-coding RNAs that are usually about 21–23 nucleotides in length. These sequences suppress gene expression by altering the stability of gene transcripts and also by targeting the transcripts for degradation although miRNA may also lead to an increase in gene transcription (Mathers et al. 2010). Many miRNAs have now been identified and may regulate a large percentage of genes in mammals (Esquela-Kersher and Slack 2006).

X.2 Cancer epigenetics and dietary intervention

Environmental factors such as the diet are well known to influence gene expression and to contribute to cancer through epigenetic mechanisms (Herceg 2007). To illustrate the importance of this, it has been reported that over half of the gene defects that occur in cancer are through epigenetic alterations as compared to genetic mutations (Issa 2008). General DNA hypomethylation not uncommonly occurs in cancer cells while gene-specific hypermethylation often leads to inactivation of key genes such as the tumor suppressors (Baylin et al. 1998). It is thought that these changes in DNA methylation play an early role in cancer genesis and lead to aberrations in cellular proliferation as well as immortalization of previously normal cells. Changes in histone modifications are also prevalent in cancer cells. For example, increased activity of the HDACs is a very common feature of cancer cells and can lead to tumorigenesis through effects on epigenetic gene expression (Dokmanovic and Marks 2005). Alterations in miRNA are also common in cancer and this occurs in many cases through defects in the expression of genes that play a role in cancer initiation or progression (Esquela-Kersher and Slack 2006). Perhaps most importantly, a growing interest has been the collective interactions of epigenetic processes in the control of gene regulation aberrations in cancer. For instance, it is not uncommon for epigenetic mechanisms to act in concert to lead to alterations in gene expression in cancer cells (Esteller 2008).

X.2.1 The epigenetics diet in cancer prevention and treatment

Many natural dietary agents which consist of bioactive compounds have been shown to be effective in cancer prevention and treatment and these nutraceuticals often mediate favorable epigenetic changes (Meeran et al. 2010a; Su et al. 2012). In fact, we have suggested an “epigenetics diet” that impacts the epigenome and that may be used in conjunction with other cancer prevention and chemotherapeutic strategies (Hardy and Tollefsbol 2011).

One of the foremost compounds that have been shown in a vast number of studies to have anticancer properties is (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) of green tea. Many studies have shown a positive correction between green tea (EGCG) consumption and the inhibition of numerous cancers (Kim et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2011; Shanmugan et al. 2011). Although EGCG has varied effects on cancer cells such as antioxidant properties, it has also been shown to have important epigenetic effects in that it can inhibit DNMT activity by directly interacting with the DNMTs (Fang et al. 2003). This can effectively lead to the reversal of tumor suppressor epigenetic silencing of cancer cells and induce apoptosis of these cells. Further, we have found that the inhibition of DNMTs by EGCG can lead to the suppression of telomerase in cancer cells by down-regulating hTERT (Mittal et al. 2004; Berletch et al. 2008). hTERT activity in cancer cells is associated with increased DNA methylation of its gene regulatory region due to repressors binding to its promoter (Berletch et al. 2008). Since telomerase is central to tumor progression, this EGCG-mediated down-regulation of telomerase activity may have major implications in cancer prevention and treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of components of the epigenetics diet on epigenetics, telomerase (hTERT) and aging and cancer. Plant products such as sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) (structures shown) modify epigenetic processes that can have a direct impact on aging and cancer. They also lead to the down-regulation of hTERT which is central to both aging and cancer. The mechanisms for epigenetic modifications of the phytochemicals can vary depending on the particular compound. Glucose restriction also can impact epigenetic processes and affect aging and cancer.

Another key dietary component that has epigenetic effects is sulforaphane (SFN) of cruciferous vegetable such as broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, cabbage and kale. However, although we have shown that SFN can inhibit DNMT1 and 3A (Meeran et al. 2010b), its most powerful effects are through inhibition of HDAC activity (Myzak et al. 2007; Dashwood and Ho 2008; Schwab et al. 2008; Nian et al. 2009). As aforementioned, HDACs are often increased in cancer cells and inhibition of HDAC activity by SFN may have considerable potential in preventing HDAC increases in cancer cells. Since hTERT is also controlled though histone acetylation/deacetylation (Daniel et al. 2012), we tested whether SFN may have an impact on hTERT gene regulation in breast cancer cells. We found that SFN treatment of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells leads to a dose- and time-dependent down-regulation of hTERT (Fig. 1). The SFN-induced hyperactylation facilitated the binding of many hTERT repressor proteins such as MAD1 and CTCF to the hTERT gene regulatory region (Meeran et al. 2010b). We also found that depletion of CTCF using siRNA attenuated the SFN-induced hTERT down-regulation in breast cancer cells (Meeran et al. 2010b).

Although dietary compounds such as EGCG in green tea and SFN in cruciferous vegetables have many other effects, it is clear that these compounds can affect the epigenetic control of key genes and greatly influence the initiation and progression of cancer (Meeran et al. 2010a). In addition to EGCG and SFN, a number of other dietary compounds are also quite effective in cancer prevention. For instance, curcumin (tumeric), resveratrol (grapes and red wine) and genistein (soybeans) as well as many other phytochemicals have created considerable excitement for their epigenetic potential (Meeran et al. 2010a). We feel that a diet consisting of epigenetic-modifying foods and beverages could have a major impact on the incidence of cancer worldwide and have therefore encouraged the epigenetic diet as a means to not only prevent cancers, but also to perhaps treat many early stage cancers (Hardy and Tollefsbol 2011). It is also highly feasible that a combination of these phytochemicals in the diet may show synergistic effects to further reduce the incidence of cancer (Meeran et al. 2012).

X.3 Aging epigenetics: The impact of dietary factors

The single most important risk factor for developing cancer is age and therefore many investigations have explored the role of epigenetics in both cancer and aging with the intention that there may be links between these two important biological processes. In fact, as with cancer, aging is associated with general genomic hypomethylation and regional or gene-specific hypermethylation (Mays-Hoopes 1989; Issa 1999) which may be due to changes in the expression of the DNMTs (Lopatina et al. 2002; Casillas et al. 2003). These modulations in DNA methylation during aging likely contribute to a number of changes in the regulation of epigenetically-controlled genes such as hTERT to contribute to the aging process (Liu et al. 2004). Moreover, histone modifications appear to play a major role in aging. In fact, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is a class III NAD+-dependent HDAC that has shown remarkable effects on aging through increasing the lifespan of a diverse range of animal models (Cohen et al. 2004; Kanfi et al. 2008). The SIRT1 enzyme appears to be an important nutrient sensor linked to metabolic rate. The redox potential, simplified as the NAD/NADH ratio, may be important in regulating SIRT1 activity which is a key indicator for oxygen consumption and the respiratory chain. Although many other epigenetic changes occur during the aging process, the regulation of DNA methylation and histone modifications as well as epigenetic control of hTERT and the role of SIRT1 in modulating aging biological processes have captured considerable interest.

3.1. Nutrient quantities, epigenetics and aging

As aforementioned, not only is the quality of the diet an important factor, but the quantity of nutrients consumed is also a major player in cancer and aging. Caloric restriction (CR) is the most effective intervention into the aging process and maximum lifespan and it is mediated in part by epigenetic mechanisms (Sinclair 2005; Weindruch et al. 1986). The restriction of total calories by 25–60% relative to normally fed controls wihle providing essential nutrients can lead to a 50% increase in lifespan (Colman et al. 2009; Cruzen and Coleman 2009; Holloszy and Fontana 2007, Li et al. 2011). DNA methylation may be altered in response to CR through its effects on specific gene loci leading to increased longevity (Hass et al. 1993). Moreover, SIRT1, an important HDAC in the aging process, is strongly linked to CR. For example, many studies have shown that its activity is affected by CR both in vitro and in vivo (Cohen et al. 2004; Lin et al. 2000; Guarente and Picard 2005; Leibiger and Berggren 2006). The longevity-extension effects of sirtuin were originally discovered in yeast (Guarente and Picard 2005) and activation of SIRT1 is often observed in various tissues of animals subjected to CR while inactivation of SIRT1 may lead to ablation of the lifespan-extending effects of CR. It is therefore apparent that epigenetic processes are not only central to the aging process, but that they are involved with key mediators of aging such as DNA methylation and SIRT1.

3.2 The epigenetics diet and aging

Resveratrol, a dietary polyphenol phytochemical, is an important mediator of CR and acts as a SIRT1 mimic that leads to increased longevity both in vitro and in vivo (Subramanian et al. 2010; Barger et al. 2008; Wood et al. 2004; Bass et al. 2007). Besides resveratrol, many other polyphenols such as EGCG have been shown to have beneficial effects on the aging process (Queen and Tollefsbol 2010). Other epigenetic diet components such as cruciferous vegetables and soybeans may also have advantageous effects on longevity through their cancer preventive properties (Meeran et al. 2010a; Li et al 2009; Li et al. 2011). For instance, consumption of components of the epigenetics diet over a period of time may lead to a decrease in age-associated diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease (Mathers 2006).

3.3 Glucose-restriction and extension of the Hayflick limit

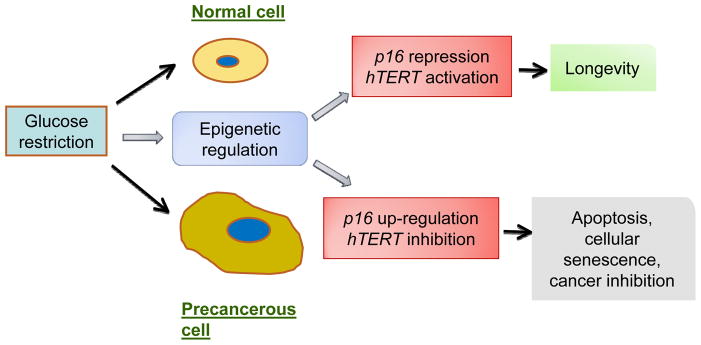

The Hayflick limit refers to the cellular senescence process that is considered to be fundamental to biological aging. Since studies of CR have been confined to analysis of the organism longevity (including single-cell yeast), we sought to test whether CR could affect the Hayflick limit in mammalian systems. Moreover, the effects of CR on human aging have not yet been resolved largely because of the impracticality of CR studies using relatively long-lived human populations. Since cellular senescence is considered a fundamental basis of aging, we restricted glucose in cultures of human fibroblast cells and monitored the Hayflick limit of the cells (Li et al. 2010). The human cells that received only about 15 mg/L of glucose had a significantly reduced lifespan as compared to control human cells that received the normal level of 4.5 g/L of glucose in culture. We further noted that epigenetic alterations occurred in these cells in response to glucose restriction that led to a relatively modest increase (compared to cancer cells) in hTERT and a decrease in p16, a gene which slows cellular replication. We found that the epigenetic changes in these cells in response to CR were at least in part due to changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications in these cells (Fig. 2). Further, precancerous cells were found to have the opposite effects on hTERT and p16 in response to glucose restriction and to lead to epigenetic-induced apoptosis of the cells (Li et al. 2010) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of glucose restriction on longevity and cancer inhibition through epigenetic regulation. Glucose restriction can impact epigenetic regulation in both normal and cancer cells. In normal cells it leads to p16 repression and hTERT activation to extend the Hayflick limit. In precancerous cells, the opposite effects on p16 and hTERT lead to apoptosis, cellular senescence and cancer inhibition of the glucose restricted cells.

In additional investigations, our studies have indicated that SIRT1 becomes elevated in the glucose-restricted human cells that leads to lifespan extension through epigenetic effects of SIRT1 on p16 as well as genetic effects of SIRT1 on p16 through the Akt/p70S6K1 pathway (Li and Tollefsbol 2011). Therefore, CR is effective in extending the lifespan of not only animals, but also of their individual cells. Since the Hayflick limit is a basic aspect of aging and there were no metabolic systemic factors involved in these studies, this suggests that CR works primarily at the cellular senescence level and that an important mediator of cellular senescence and aging is changes in epigenetic mechanisms in response to CR.

X.4 Conclusions

Epigenetic mechanisms are central to many aspects of both aging and cancer and dietary factors are important means of alleviating many of the adverse effects of these biological processes. Both the quality and the quantity of the diet are crucial in healthy aging and also significantly impact cancer. The quality of the diet is illustrated though the epigenetics diet consisting of consumption of phytochemicals that modulate epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNA. Substantial data that have been accumulated worldwide clearly show that the epigenetics diet has considerable potential in not only preventing cancer, but also in reducing the incidence of age-related diseases. The quantity of the diet also has epigenetic effects in that reduction of calories impacts many epigenetic mechanisms such as the activity of SIRT1 which is an epigenetic mediator of a number of cellular processes. We have shown that CR at the cellular level can extend the lifespan of human cells and is likely a fundamental basis of the life-extending process of the epigenetic effects of CR. Many questions remain regarding the role of epigenetics in cancer and aging, but it is now clear that epigenetic mechanisms are basic aberrations in both cancer and aging and that the epigenetics diet is moving to the forefront of cancer and aging research as a safe and efficacious means to reduce the morbidity and mortality of these biological processes that claim so many human lives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (RO1 CA129415), the American Institute for Cancer Research, and the Norma Livingston Foundation.

Abbreviations

- CR

caloric restriction

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferases

- EGCG

(−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- HAT

histone methyltransferases

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- hTERT

human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- miRNA

microRNA

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- SFN

sulforaphane

- siRNA

short-interfering RNA

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

References

- Barger JL, Kayo T, Vann JM, et al. A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3(6):e2264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass TM, Weinkove D, Houthoofd K, et al. Effects of resveratrol on lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:546–552. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin SB, Herman JG, Graff JR, et al. Alterations in DNA methylation: a fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;72:141–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berletch JB, Liu C, Love WK, et al. Epigenetic and genetic mechanisms contribute to telomerase inhibition by EGCG. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:509–519. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas MA, Jr, Lopatina N, Andrews LG, et al. Transcriptional control of the DNA methyltransferases is altered in aging and neoplastically-transformed human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;252:33–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1025548623524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PN, Chu SC, Kuo WH, et al. Epigallocatechin-3 gallate inhibits invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and tumor growth in oral cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:3836–3844. doi: 10.1021/jf1049408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AL, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC. Enhanced histone acetylation and transcription: a dynamic perspective. Mol Cell. 2006;23:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305:390–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1099196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science. 2009;325:201–204. doi: 10.1126/science.1173635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruzen C, Colman RJ. Effects of caloric restriction on cardiovascular aging in non-human primates and humans. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M, Peek GW, Tollefsbol TO. Regulation of the human catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) Gene. 2012;498:135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashwood RH, Ho E. Dietary agents as histone deacetylase inhibitors: sulforaphane and structurally related isothiocyanates. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(Suppl 1):S36–S38. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokmanovic M, Marks PA. Prospects: histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:293–304. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang MZ, Wang Y, Ai N, et al. Tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits DNA methyltransferase and reactivates methylation-silenced genes in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7563–7570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L, Picard F. Calorie restriction--the SIR2 connection. Cell. 2005;120:473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy TM, Tollefsbol TO. Epigenetic diet: impact on the epigenome and cancer. Epigenomics. 2011;3:503–518. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass BS, Hart RW, Lu MH, et al. Effects of caloric restriction in animals on cellular function, oncogene expression, and DNA methylation in vitro. Mutat Res. 1993;295:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(93)90026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herceg Z. Epigenetics and cancer: towards an evaluation of the impact of environmental and dietary factors. Mutagenesis. 2007;22:91–103. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Caloric restriction in humans. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:709–712. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP. Aging, DNA methylation and cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1999;32:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(99)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP. Cancer prevention: epigenetics steps up to the plate. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1:219–222. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanfi Y, Peshti V, Gozlan YM, et al. Regulation of SIRT1 protein levels by nutrient availability. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2417–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Amin AR, Shin DM. Chemoprevention of head and neck cancer with green tea polyphenols. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:900–909. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibiger IB, Berggren PO. Sirt1: a metabolic master switch that modulates lifespan. Nat Med. 2006;12:34–36. doi: 10.1038/nm0106-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tollefsbol TO. p16(INK4a) suppression by glucose restriction contributes to human cellular lifespan extension through SIRT1-mediated epigenetic and genetic mechanisms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu L, Andrews LG, et al. Genistein depletes telomerase activity through cross-talk between genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:286–296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu L, Tollefsbol TO. Glucose restriction can extend normal cell lifespan and impair precancerous cell growth through epigenetic control of hTERT and p16 expression. FASEB J. 2010;24:1442–1453. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-149328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Daniel M, Tollefsbol TO. Epigenetic regulation of caloric restriction in aging. BMC Med. 2011;9:98. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SJ, Defossez PA, Guarente L. Requirement of NAD and SIR2 for life-span extension by calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2000;289:2126–2128. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wylie RC, Andrews LG, et al. Aging, cancer and nutrition: the DNA methylation connection. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatina N, Haskell JF, Andrews LG, et al. Differential maintenance and de novo methylating activity by three DNA methyltransferases in aging and immortalized fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2002;84:324–334. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers JC. Nutritional modulation of ageing: genomic and epigenetic approaches. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers JC, Strathdee G, Relton CL. Induction of epigenetic alterations by dietary and other environmental factors. Adv Genet. 2010;71:3–39. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380864-6.00001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays-Hoopes LL. DNA methylation in aging and cancer. J Gerontol. 1989;44:35–36. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.6.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeran SM, Ahmed A, Tollefsbol TO. Epigenetic targets of bioactive dietary components for cancer prevention and therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 2010a;1:101–116. doi: 10.1007/s13148-010-0011-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeran SM, Patel SN, Tollefsbol TO. Sulforaphane causes epigenetic repression of hTERT expression in human breast cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2010b;5(7):e11457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeran SM, Patel SN, Li Y, et al. Bioactive dietary supplements reactivate ER expression in ER-negative breast cancer cells by active chromatin modifications. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037748. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal A, Pate MS, Wylie RC, et al. EGCG down-regulates telomerase in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells, leading to suppression of cell viability and induction of apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:703–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myzak MC, Tong P, Dashwood WM, et al. Sulforaphane retards the growth of human PC-3 xenografts and inhibits HDAC activity in human subjects. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:227–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nian H, Delage B, Ho E, et al. Modulation of histone deacetylase activity by dietary isothiocyanates and allyl sulfides: studies with sulforaphane and garlic organosulfur compounds. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50:213–221. doi: 10.1002/em.20454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole JC, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. Activity, function, and gene regulation of the catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) Gene. 2001;269:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh TD, Oberley TD, Weindruch R. Dietary intervention at middle age: caloric restriction but not dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate increases lifespan and lifetime cancer incidence in mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1642–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen BL, Tollefsbol TO. Polyphenols and aging. Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:34–42. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M, Reynders V, Loitsch S, et al. The dietary histone deacetylase inhibitor sulforaphane induces human beta-defensin-2 in intestinal epithelial cells. Immunology. 2008;125(2):241–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam MK, Kannaiyan R, Sethi G. Targeting cell signaling and apoptotic pathways by dietary agents: role in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:161–173. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.523502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair DA. Toward a unified theory of caloric restriction and longevity regulation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:987–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LJ, Mahabir S, Ellison GL, et al. Epigenetic contributions to the relationship between cancer and dietary intake of nutrients, bioactive food components, and environmental toxicants. Front Genet. 2011;2:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2011.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian L, Youssef S, Bhattacharya S, et al. Resveratrol: challenges in translation to the clinic--a critical discussion. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5942–5948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Krishnan A, Su J, Lawrence R, et al. Regulation of immune function by calorie restriction and cyclophosphamide treatment in lupus-prone NZB/NZW F1 mice. Cell Immunol. 2004;228:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weindruch R, Walford RL, Fligiel S, et al. The retardation of aging in mice by dietary restriction: longevity, cancer, immunity and lifetime energy intake. J Nutr. 1986;116:641–654. doi: 10.1093/jn/116.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, et al. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]