Abstract

Structured treatment interruptions (STIs) have been proposed as a potential treatment strategy during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antiretroviral therapy. This still-experimental intervention requires a close monitoring of patients' plasma viremia and CD4+-T-cell counts during the treatment interruption phase. By using signal amplification of a heat-dissociated p24 antigen (p24Ag) assay, we compared p24Ag levels with levels of HIV RNA in plasma. One hundred seventy-four plasma samples were obtained from 51 chronically HIV-infected patients: 117 from patients who underwent STIs and 57 from patients who did not. Partial immune complex dissociation and clearance of those complexes by the erythrocytes were also investigated. A significant association between the two assays was observed (β = 0.23, 95% confidence interval = 0.18, 0.28; P < 0.0001), but the association was smaller in the subset of samples from patients undergoing STIs. Moreover, discordant results and lack of longitudinal intrapatient correlation between levels of p24Ag and HIV-1 RNA were higher in this group. Incomplete immune complex dissociation and binding of those complexes to erythrocytes could be contributing factors involved in the diminished detection of p24Ag. Therefore, signal amplification of a heat-dissociated p24Ag had a positive association with current HIV RNA assays in a population-based analysis. However, it might not be sensitive enough to monitor longitudinal intrapatient viremia during STIs in patients with high CD4+-T-cell counts potentially due to the production of high-affinity anti-p24 antibodies and clearance of immune complexes by erythrocytes.

Structured treatment interruptions (STIs) have been proposed as a potential treatment strategy during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antiretroviral therapy. In chronically HIV-infected individuals undergoing successful antiretroviral treatment, this strategy was initially designed to boost HIV-specific immunity through controlled exposure to autologous virus over limited periods of time, pursuing the subsequent control of the boosted immune system over viral replication in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Subsequently, the prospect of lifelong, sometimes-difficult antiretroviral regimens prompted many research groups to explore STIs as a way to reduce drug-associated toxicities. This still-experimental intervention requires a close follow-up of the patients during the interruption phase to monitor sudden increases in plasma viral load (pVL) that might produce a primary-infection-like syndrome and severe reductions in CD4 T-cell counts, with the associated risk of developing opportunistic infections (12). We had analyzed the impact of repeated STIs on virologic and immunologic parameters in a cohort of chronically HIV-1-infected patients with long-lasting viral suppression (<50 copies/ml) under highly active antiretroviral therapy before STIs (18, 19). The controlled exposure to the virus in these patients was monitored every two days during the off-therapy phases. This approach was required to investigate viral dynamics and evolution of HIV-1 during STIs (7, 8). The objective of the present study was to assess the potential usefulness of an ultrasensitive heat-dissociated p24 antigen assay (p24Ag) (2, 4, 13, 16, 20-24, 26) as a less costly alternative to pVL screening in the above-described patients undergoing STIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and specimens.

The samples analyzed in this study were obtained during randomized, prospective STI studies conducted at the Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Spain. Full details of the selection criteria are given elsewhere (18, 19). In brief, HIV-1-infected patients with CD4+-cell counts of >600 cells/μl, with a CD4/CD8 ratio of >1 sustained for a minimum of 6 months and whose plasma HIV RNA levels were below 50 copies/ml for at least 2 years before study entry were scheduled to interrupt their antiviral therapy in an intermittent manner. These criteria were chosen in order to enroll patients with well-conserved immunity and long-term viral suppression. Treatment interruptions during the first four cycles lasted for a maximum of 30 days or until pVLs reached levels higher than 3,000 copies/ml in two consecutive determinations, after which highly active antiretroviral therapy was resumed for approximately 90 days until the next STI cycle. In all cases, this resulted in suppression of plasma viremia to less than 50 copies/ml prior to the next interruption. At the fifth STI patients were off treatment for more than 12 months. Treatment regimens were fairly homogenous among patients and did not include nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. These samples constituted study group A. For comparative purposes, we also included in the study other plasma samples from antiretroviral-treatment-naive patients and treated patients who were experiencing viral breakthrough regardless of their CD4+-T-cell counts and whose pVLs were therefore detectable (mean log10 HIV-1 RNA, 4.3 [95% confidence interval {CI} = 4.0, 4.5]; mean CD4+ T cells/μl, 646 [95% CI = 537, 755]) (study group B).

HIV RNA assay.

Plasma HIV-1 RNA load was measured in 0.5 ml of frozen EDTA-plasma samples by using an Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor UltraSensitive test (Roche Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain), with a limit of detection of 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml. Viral load measurements were frequently obtained during the interruption period (median time interval was 2 days). CD4 and CD8 T-lymphocyte counts were measured by flow cytometry.

p24Ag assay.

The plasma samples were frozen at −80°C immediately after processing and stored frozen until tested. The levels of p24Ag in plasma were measured by using a signal amplification-boosted enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of the heat-dissociated p24Ag assay (16, 17). Briefly, plasma was diluted 1:6 in 0.5% Triton X-100 and heated at 100°C for 5 min in a dry heat block. Treated plasma (0.25 ml) was transferred to wells of an HIV-1 p24 core profile ELISA kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.), the wells were covered, and the plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Wells were washed with 1× wash buffer, 0.1 ml of biotinylated detector antibody was added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After a washing, 0.1 ml of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase solution was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 15 min at 37°C (ELAST amplification system; PerkinElmer Life Sciences). After a washing, 0.1 ml of biotinyl-tyramide solution was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Following a washing, 0.1 ml of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase, diluted in washing buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin, was added to the wells and the plates were incubated for 15 min at room temperature. O-phenylenediamine substrate solution (0.1 ml) was added to the wells after a washing, and the plates were inserted into a kinetic ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Palo Alto, Calif.). By using Quanti-Kin detection system software (DL3; Diagnostica Ligure s.r.l., Genoa, Italy), kinetic readings were performed during the initial 10 min of incubation (9). At the end of 30 min, the colorimetric reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.1 ml of stop solution, and the end-point reading was taken as indicated by the Quanti-Kin software. For quantitation, a cutoff corresponding to the mean plus 3 standard deviations was calculated by the Quanti-Kin software. The limit of detection of this ultrasensitive p24Ag assay was as low as 1,000 fg.

Total Ig levels in plasma.

Levels of immunoglobulins (Igs) (IgG, IgA, IgM, and IgE) in plasma from six HIV-1-seropositive patients (three positive for p24Ag and three negative for p24Ag) were determined by nephelometry. Reference Ig ranges for HIV-1-seronegative donors were as follow: IgG, 600 to 1,500 mg/dl; IgA, 70 to 400 mg/dl; IgM, 40 to 230 mg/dl; and IgE, less than 100 IU/ml.

Ig separation.

A highly enriched Ig fraction was obtained from six plasma samples from HIV-1-seropositive patients (three positive for p24Ag and three negative for p24Ag) and a seronegative donor by ammonium sulfate precipitation (1). Seven hundred microliters of plasma was mixed with 300 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight with a 50% (vol/vol) saturated ammonium sulfate solution. Subsequently, samples were centrifuged at 10,500 × g for 1 h. The pellets were resuspended in 15 ml of 1× phosphate-buffered saline and ultrafiltered using an Amicon Ultra-15 (Millipore, Barcelona, Spain) by centrifugation twice at 2,300 × g for 30 min.

Complementation assay.

Plasma and Ig purified fractions from patient samples were mixed with an equal volume of plasma obtained from a patient sample positive for p24Ag. After the mix was incubated at 37°C for 60 min, the p24Ag was measured as indicated above. This complementation assay was also performed in the presence of different concentrations of red blood cells obtained from healthy donors, in order to measure the binding of p24 immune complexes to CD35 on erythrocytes.

Western blotting.

The detection of anti-p24 antibodies was assessed by Western blotting (INNO-LIA HIV confirmation; Innogenetics).

Statistical analysis.

p24Ag and HIV RNA concentrations were log10 transformed for all analyses. Logistic regressions with generalized estimating equations were used to compare proportions of concordant pairs of p24Ag and HIV RNA for detection between groups. Mixed regression models were used to assess association between p24Ag levels, HIV RNA levels, and CD4+-T-cell counts and were also used to compare p24Ag levels between groups. The use of mixed and generalized estimating equation models allows the adjustment for dependency existing among observations for samples from the same patient. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.), and a two-sided significance level of 5% was always used.

RESULTS

One hundred seventy-four plasma specimens were obtained from 51 chronically HIV-infected patients: 117 from patients who underwent STIs (group A) and 57 from patients who did not (group B). Specimens from the same patient always belonged to different time points. The HIV-1 subtype for all patients was subtype B as assessed by pol sequencing (data not shown).

Association between p24Ag levels, pVLs, and CD4+-T-cell counts.

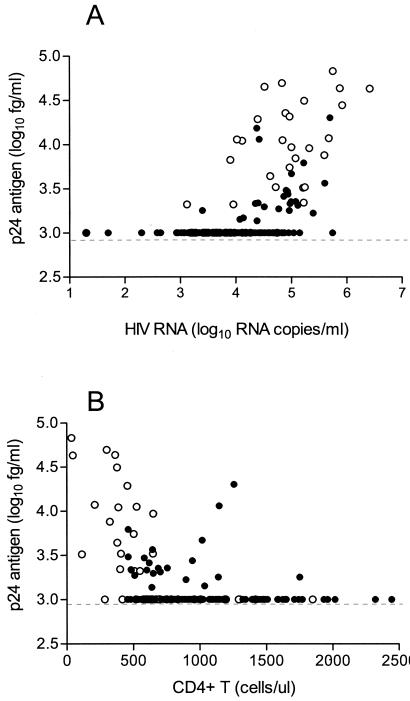

HIV RNA and p24Ag assays were significantly associated (regression slope, β = 0.23; 95% CI = 0.18, 0.28; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). However, the association was higher in the patients who did not undergo STI, group B (β = 0.45; CI = 0.34, 0.56; P < 0.0001), than in those who did, group A (β = 0.10, CI = 0.06, 0.14, P < 0.0001). The CD4+-T-cell counts were inversely associated with the p24Ag level (β = −0.0004; CI = −0.0006, −0.0003; P < 0.0001), but the association was almost negligible (Fig. 1B). The association between p24Ag and HIV RNA levels was still observed after adjusting for CD4+-T-cell counts for both groups combined (β = 0.19; CI = 0.14, 0.24; P < 0.0001) and within each group: group A (β = 0.09; CI = 0.05, 0.13; P < 0.0001) and group B (β = 0.32; CI = 0.20, 0.43; P < 0.0001). The association between p24Ag and CD4+-T-cell counts was also observed after adjusting for HIV RNA for combined groups (β = −0.0003; CI = −0.0004, −0.0001; P < 0.0001) and for group B (β = −0.0005; CI = −0.0009, −0.0001; P = 0.012) and diminished for group A (P = 0.19).

FIG. 1.

(A) Comparison of HIV RNA concentrations (Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor UltraSensitive test; Roche Diagnostics) and the p24Ag levels measured by signal amplification-boosted ELISA. Symbols: solid circles, 119 plasma specimens from 16 patients undergoing STIs; open circles, 55 plasma specimens from 35 patients with treatment failure that did not undergo STIs. (B) Comparison of CD4+-T-cell counts and the p24Ag levels measured by signal amplification-boosted ELISA. Symbols: solid circles, 113 blood specimens from 16 patients undergoing STIs; open circles, 46 blood specimens from 35 patients with treatment failure that did not undergo STIs. ul, microliter.

Differences between groups.

Overall, 33% (57 of 174) of the samples were concordant for both p24Ag and pVL (i.e., both assays positive or both negative), including 24% of the analyzed samples in group A and 51% of those in group B (odds ratio = 3.13; 95% CI, 1.33, 7.14; P = 0.008), suggesting that the likelihood of having concordance is 3 times higher in group B than in group A (Table 1). All discordant results clustered in the status of detectable pVL but undetectable p24Ag. Plasma samples obtained from group A had lower p24Ag levels than the rest of the screened samples (the mean p24Ag level in group A was lower than that in group B by 0.4 [CI = 0.21, 0.57; P < 0.0001]).

TABLE 1.

Concordant and discordant results for viral load and p24Ag resultsa

| Group | No. (%) of results showing:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordance

|

Disconcordance

|

|||

| p24 Ag+ HIV RNA+ | p24 Ag− HIV RNA− | p24 Ag− HIV RNA+ | p24 Ag+ HIV RNA− | |

| A | 24 (20) | 5 (4) | 90 (76) | 0 (0) |

| B | 27 (49) | 1 (2) | 27 (49) | 0 (0) |

Data were considered either positive or negative based on the limit of detection of the assays.

In terms of pVL, the p24Ag assay detected 82% (18 of 22) of the specimens with a pVL of >100,000 copies/ml, 39% (29 of 74) of the specimens with a pVL between 10,000 and 100,000 copies/ml, 7% (4 of 61) of the specimens with a pVL between 1,000 and 10,000 copies/ml, and 0% (0 of 17) of the specimens with a pVL between 50 and 1,000 copies/ml. These percentages were always higher in group B that in group A for the same range of pVL. Regarding CD4+-T-cell counts, p24Ag was detected in 10% (6 of 58) of the specimens with a CD4 count of >1,000 cells/μl, 22% (18 of 81) of the specimens with a CD4 count between 500 and 1,000 cells/μl, and 81% (17 of 21) of the specimens with a CD4 count of <500 cells/μl.

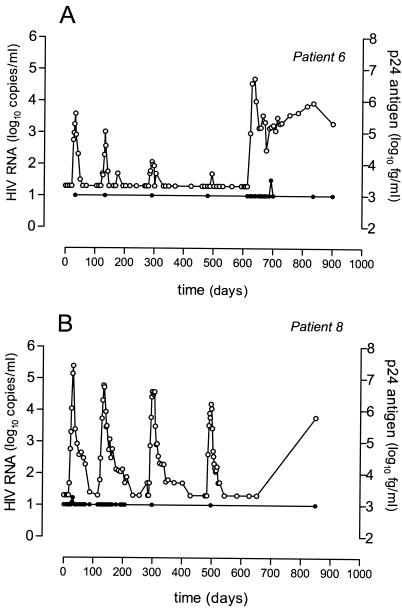

Lack of longitudinal intrapatient correlation between levels of p24Ag and HIV-1 RNA.

Subjects that underwent STIs in our cohort presented pVL rebound above the limit of detection of the assay within days to weeks after therapy was withdrawn. However, there was not a significant increase in p24Ag levels during STIs, despite pVLs that reached more than 10,000 HIV RNA copies/ml (Fig. 2). Such observations remained stable even during the fifth STI, when patients stopped their treatment up to 12 months. In all cases the CD4+-T-lymphocyte count remained above 500 cells/μl. Of note, p24Ag levels were undetectable even when pVL went above 100,000 HIV RNA copies/ml. Thus, no intrapatient correlation could be established between the dynamics of pVL and p24Ag levels in our cohort of patients undergoing STIs.

FIG. 2.

Longitudinal intrapatient comparison of viral load and p24Ag level measured by signal amplification-boosted ELISA during repetitive STI in chronically HIV-1-infected patients. Symbols: open circles, viral load; solid circles, p24Ag measurements. Viral load peaks coincide with about 4-week treatment interruptions. The last treatment interruption lasted for more than a year. The lowest limit of detection for the viral load assay was 50 HIV RNA copies/ml, and that for the p24Ag assay was 1,000 fg/ml. (A) Patient 6; (B) patient 8. These two patients are representative examples of the 14 other patients included in the same or a similar STI protocol.

Because a total of 74 out of 78 plasma specimens with HIV-1 RNA levels between 50 and 10,000 copies/ml were p24Ag negative, we considered the possibility that viral epitopes in those HIV-infected patients were not recognized by the monoclonal antibody. Thus, we cocultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells of those blood specimens with phytohemagglutinin-stimulated donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells to obtain virus isolates. The in vitro-obtained virus always tested positive for p24Ag, indicating that the lack of detection in plasma specimens was not due to the viral protein itself.

Factors involved in the diminished detection of p24Ag.

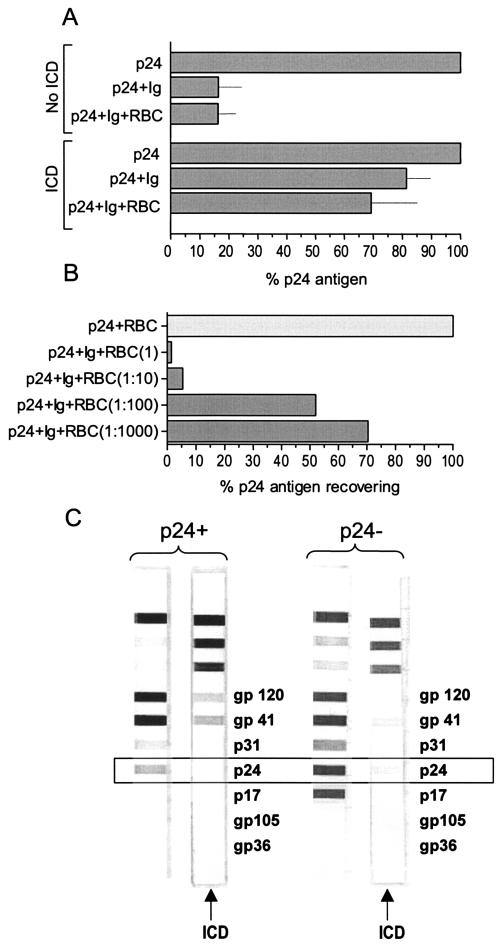

Due to the higher level of CD4+-T-cell counts in the group of patients undergoing STIs, we decided to investigate whether these plasma samples might contain high-affinity p24-specific antibodies which complex the antigen-resisting heat dissociation, hence causing underdetection or false-negative results. Thus, we incubated the total fraction of Ig obtained from plasma of a patient with consistently undetectable p24Ag with plasma from a patient with detectable p24Ag, and then we performed the boosted p24 ELISA again. In the absence of heat immune complex dissociation, the Ig reduced the p24Ag detection about 80% (Fig. 3A). Although the heat immune complex dissociation treatment increased the p24Ag levels, there still was a 20% reduction in the p24Ag detection levels. When erythrocytes from healthy donors were added to these complementation mixtures, p24Ag was further reduced, presumably due to adsorption of the immune complexes to the immune adherence receptor CD35 expressed on red blood cells (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, recovering of p24Ag was inversely associated with erythrocyte concentration (Fig. 3B). These observations were in agreement with the quantification of anti-p24 antibodies in plasma with and without immune complex heat dissociation (Fig. 3C). Samples from patients with conserved immunity that followed STIs in the absence of detectable levels of p24Ag still showed low but detectable levels of anti-p24 antibodies after immune complex heat dissociation. The quantification of different Igs in the plasma of various patients did not show a specific type of Igs that was overexpressed in patients with persistently negative p24Ag (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Effect of adding Igs purified from a plasma specimen that was systematically negative for p24Ag to a plasma sample from a patient with a detectable p24Ag level (here normalized to 100% in the first and fourth bars from the top). The first to third bars show the reduction in p24Ag detection in the absence of immune complex dissociation (ICD). The fourth to sixth bars show the reduction in p24Ag detection in the presence of ICD. Each bar represents the mean of six values. Lines indicate standard error. RBC, red blood cells. (B) Effect of RBC in recovering p24Ag. Results for the RBC incubated in the presence of p24Ag (light grey bar) and serial dilutions of RBC incubated in the presence of p24Ag and Igs of an HIV-seropositive patient included in group A in the presence of ICD (dark grey bars) are shown. (C) Detection of p24-specific antibodies by Western blotting in the presence and absence of ICD in plasma specimens from a patient with different p24Ag responses. Higher levels of p24-specific antibodies could be observed in a plasma sample that was p24 negative (right panel). Anti-p24 antibodies were completely eliminated by heat dissociation in a specimen from a p24-positive patient (left panel), while a fraction remained detectable in a specimen from a p24-negative patient (right panel).

DISCUSSION

Plasma HIV-1 RNA load has become the standard-of-care test for monitoring HIV-infected subjects, including the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy. However, this test requires a complex and expensive technology that limits its use where financial resources for health care are limited (25). The HIV-1 RNA assay may also be costly in those situations where patients require intensive monitoring. This is the case of the STIs during chronic HIV infection, aimed to reinforce the immune system or to reduce drug toxicities. In this scenario, reintroduction of therapy is frequently guided by viral load measurements in order to avoid deterioration of the clinical and immunological status of the patient. Alternative methods are currently under scrutiny (3, 5, 10, 16, 27).

In chronically HIV-infected patients with long-term HIV RNA suppression and well-conserved immunity (defined as CD4/CD8 ratio of >1 and CD4+-T-cell counts of >600 cells/μl), levels of p24Ag in plasma remained below the limit of detection during antiretroviral treatment interruptions, even when HIV-1 RNA levels rose over 10,000 copies/ml. Therefore, no longitudinal intrapatient correlation could be established between pVL and p24Ag level determinations in our cohort of patients undergoing STIs.

The finding explained why the association between the mean p24Ag and HIV-1 RNA was lower in samples from STI patients than in those from patients who did not undergo STIs.

Results in the latter group of specimens were similar to those found by Pascual et al. (17) when they compared the same p24Ag assay with the standard Roche Amplicor Monitor assay (version 1.0), with a limit of quantification of 400 copies/ml. We extended the correlation to CD4+ T cells, finding an inverse correlation between p24Ag level and CD4+-T-cell count that was also more marked in the non-STI group.

A total of 80% of samples in group A and 51% in group B had p24Ag levels below the limit of detection. We imputed a p24Ag level below the detection limit using HIV RNA, CD4, and CD8. The findings of the above analyses appeared unchanged by replacement of the original p24Ag values with the imputed values.

It has to be emphasized that our study did not pursue the establishment of the performance of the p24Ag assay in comparison with the HIV RNA assay. Our samples were initially selected based on STI protocols (group A). Most of them had CD4 cell counts of >500/μl, while few studies evaluating the performance of this p24Ag assay had looked into this type of patient. The rest of our samples (group B) were included as control samples. Therefore, our specimen selection does not necessarily represent the clinical sample cohorts tested by others. However, the results clearly show that quantification of p24Ag, even by using highly sensitive methods, might be hampered in specific patients with detectable HIV RNA. This peculiarity is probably more related to the immunological characteristics of the patients selected to have their treatment interrupted than a consequence of the interruption treatment strategy itself. Of note, despite sustained CD4+-T-cell levels, p24-specific CD4 T-helper responses were weak and transient in patients from group A during STIs (18). It is very plausible that patients with high levels of CD4 and repeated boosts of HIV due to the structured interruptions have antibodies to p24 with much higher affinity that those with low CD4, and indeed a criticism of the use of p24Ag as a surrogate marker is that often it is hindered by the presence of p24Ag bound to Igs (6, 15). In the present assay, antibody-complexed p24 is increasingly released by boiling the plasma sample 5 min. However, the fact that some specimens still had no detectable p24Ag regardless of their viral load suggests the presence of high-affinity immune complexes in plasma, which might be partially resistant to heat dissociation, precluding the viral protein from being detected by the assay. This seemed to be the case in at least some of our p24Ag-negative patients. Western blots of immune-dissociated complexes showed persistent detection of anti-p24 antibodies in patients systematically negative for p24Ag. This was the case of patient number 8 (Fig. 2). Conversely, anti-p24 antibodies were completely absent in p24-positive specimens. Moreover, the addition of either plasma or purified Igs from p24Ag-negative patients' samples to p24Ag-positive specimens significantly reduced the detection of p24Ag in the latter. Despite this fact, we quantified different Igs in the plasma of various patients, and as expected, we could not find a specific class of Igs that was overexpressed in patients persistently negative for p24Ag. Taken together, these results suggest that secretion of Igs that bound to p24Ag with high affinity might be responsible for reduced sensitivity of the p24Ag detection, and it is likely that STIs might help to maintain high levels of Igs.

The fact that erythrocytes bind HIV-1 immune complexes (11) also has to be considered. Opsonization of particulate pathogens by antibodies and complement can lead to their binding to the complement receptor 1 (CR1 or CD35), also termed immune adherence receptor, which is expressed on erythrocytes (14). Thus, HIV-1 immune complexes bound to erythrocytes via CR1 facilitate the clearance of viral proteins from the bloodstream by transferring them to macrophages in the liver and spleen. Therefore, increased removal of p24 immune complexes might lead to low presence of the viral protein in plasma.

Although speculative, undetectable levels of p24Ag in the cohort of selected STI patients might also be the result of reduced viral pathogenesis. Thus, CD4+-T-cell counts did not significantly decrease during STIs (18) despite pVL rebounds. This observation might be in agreement with the suggestion that p24 concentrations may indeed be better correlated with ensuing CD4 depletion rates and survival than the concentrations of particle-associated viral RNA (24).

Thus, quantification of HIV load in plasma by signal amplification-boosted ELISA detection of p24Ag after heat-mediated immune complex dissociation has an improved performance in terms of sensitivity and wider dynamic range than prior p24Ag detection-based assays. In a population-based analysis a positive association was found with respect to current HIV RNA assays. Therefore, the p24Ag assay might be a useful monitoring tool in certain situations, such as identification of seroconverters (17), early diagnosis of infection in HIV-1-exposed infants (22, 27), prognosis for adults with early-stage disease (26), or monitoring patients in resource-poor countries (17). However, it might not be sensitive enough to monitor longitudinal intrapatient viremia during STIs in patients with high CD4+-T-cell counts potentially due to the production of high-affinity anti-p24 antibodies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants FIS 01/1122 and Red G03/173. J.G.P. was supported by grant BEFI 01/9067. J.M.-P. was supported by contract FIS 99/3132 from the Fundacio Institut d'Investigacio en Ciencies de la Salut Germans Trias i Pujol in collaboration with the Spanish Health Department. We thank the Vanderbilt Meharry Developmental Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI 54999) for stimulating this collaboration and for support for A. Shintani.

We thank M. Juan for helpful suggestions and V. Miller for critical reading of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrew, S. M., and J. A. Titus. 1998. Induction of immune responses. Curr. Protocols Immunol. 1:272-273. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boni, J., M. Opravil, Z. Tomasik, M. Rothen, L. Bisset, P. J. Grob, R. Luthy, and J. Schupbach. 1997. Simple monitoring of antiretroviral therapy with a signal-amplification-boosted HIV-1 p24 antigen assay with heat-denatured plasma. AIDS 11:F47-F52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun, J., J. C. Plantier, M. F. Hellot, E. Tuaillon, M. Gueudin, F. Damond, A. Malmsten, G. E. Corrigan, and F. Simon. 2003. A new quantitative HIV load assay based on plasma virion reverse transcriptase activity for the different types, groups and subtypes. AIDS 17:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgisser, P., P. Vernazza, M. Flepp, J. Boni, Z. Tomasik, U. Hummel, G. Pantaleo, J. Schupbach, et al. 2000. Performance of five different assays for the quantification of viral load in persons infected with various subtypes of HIV-1. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 23:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Baar, M. P., M. W. van Dooren, E. de Rooij, M. Bakker, B. van Gemen, J. Goudsmit, and A. de Ronde. 2001. Single rapid real-time monitored isothermal RNA amplification assay for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from groups M, N, and O. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1378-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiscus, S. A., J. D. Folds, and C. M. van der Horst. 1993. Infectious immune complexes in HIV-1-infected patients. Viral Immunol. 6:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frost, S. D. 2002. Dynamics and evolution of HIV-1 during structured treatment interruptions. AIDS Rev. 4:119-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost, S. D. W., J. Martinez-Picado, L. Ruiz, B. Clotet, and A. J. Leigh Brown. 2002. Viral dynamics during structured therapy interruptions of chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 76:968-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giacomini, M., J. L. McDermott, A. A. Giri, I. Martini, F. B. Lillo, and O. E. Varnier. 1998. A novel and innovative quantitative kinetic software for virological colorimetric assays. J. Virol. Methods 73:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayden, M. S., E. H. Palacios, and R. M. Grant. 2003. Real-time quantitation of HIV-1 p24 and SIV p27 using fluorescence-linked antigen quantification assays. AIDS 17:629-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess, C., T. Klimkait, L. Schlapbach, V. Del Zenero, S. Sadallah, E. Horakova, G. Balestra, V. Werder, C. Schaefer, M. Battegay, and J. A. Schifferli. 2002. Association of a pool of HIV-1 with erythrocytes in vivo: a cohort study. Lancet 359:2230-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilby, J. M., P. A. Goepfert, A. P. Miller, J. W. Gnann, Jr., M. Sillers, M. S. Saag, and R. P. Bucy. 2000. Recurrence of the acute HIV syndrome after interruption of antiretroviral therapy in a patient with chronic HIV infection: a case report. Ann. Intern. Med. 133:435-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ledergerber, B., M. Flepp, J. Boni, Z. Tomasik, R. W. Cone, R. Luthy, and J. Schupbach. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 p24 concentration measured by boosted ELISA of heat-denatured plasma correlates with decline in CD4 cells, progression to AIDS, and survival: comparison with viral RNA measurement. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1280-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindorfer, M. A., C. S. Hahn, P. L. Foley, and R. P. Taylor. 2001. Heteropolymer-mediated clearance of immune complexes via erythrocyte CR1: mechanisms and applications. Immunol. Rev. 183:10-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonell, K. B., J. S. Chmiel, L. Poggensee, S. Wu, and J. P. Phair. 1990. Predicting progression to AIDS: combined usefulness of CD4 lymphocyte counts and p24 antigenemia. Am. J. Med. 89:706-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nadal, D., J. Boni, C. Kind, O. E. Varnier, F. Steiner, Z. Tomasik, and J. Schupbach. 1999. Prospective evaluation of amplification-boosted ELISA for heat-denatured p24 antigen for diagnosis and monitoring of pediatric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1089-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pascual, A., A. Cachafeiro, M. L. Funk, and S. A. Fiscus. 2002. Comparison of an assay using signal amplification of the heat-dissociated p24 antigen with the Roche Monitor human immunodeficiency virus RNA assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2472-2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruiz, L., G. Carcelain, J. Martinez-Picado, S. Frost, S. Marfil, R. Paredes, J. Romeu, E. Ferrer, K. Morales-Lopetegi, B. Autran, and B. Clotet. 2001. HIV dynamics and T-cell immunity after three structured treatment interruptions in chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 15:F19-F27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz, L., J. Martinez-Picado, J. Romeu, R. Paredes, M. K. Zayat, S. Marfil, E. Negredo, G. Sirera, C. Tural, and B. Clotet. 2000. Structured treatment interruption in chronically HIV-1 infected patients after long-term viral suppression. AIDS 14:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schupbach, J. 2002. Measurement of HIV-1 p24 antigen by signal-amplification-boosted ELISA of heat-denatured plasma is a simple and inexpensive alternative to tests for viral RNA. AIDS Rev. 4:83-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schupbach, J., J. Boni, M. Flepp, Z. Tomasik, H. Joller, and M. Opravil. 2001. Antiretroviral treatment monitoring with an improved HIV-1 p24 antigen test: an inexpensive alternative to tests for viral RNA. J. Med. Virol. 65:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schupbach, J., J. Boni, Z. Tomasik, J. Jendis, R. Seger, C. Kind, et al. 1994. Sensitive detection and early prognostic significance of p24 antigen in heat-denatured plasma of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected infants. J. Infect. Dis. 170:318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schupbach, J., M. Flepp, D. Pontelli, Z. Tomasik, R. Luthy, and J. Boni. 1996. Heat-mediated immune complex dissociation and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay signal amplification render p24 antigen detection in plasma as sensitive as HIV-1 RNA detection by polymerase chain reaction. AIDS 10:1085-1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schupbach, J., Z. Tomasik, D. Nadal, B. Ledergerber, M. Flepp, M. Opravil, and J. Boni. 2000. Use of HIV-1 p24 as a sensitive, precise and inexpensive marker for infection, disease progression and treatment failure. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 16:441-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stephenson, J. 2002. Cheaper HIV drugs for poor nations bring a new challenge: monitoring treatment. JAMA 288:151-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterling, T. R., D. R. Hoover, J. Astemborski, D. Vlahov, J. G. Bartlett, and J. Schupbach. 2002. Heat-denatured human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protein 24 antigen: prognostic value in adults with early-stage disease. J Infect. Dis. 186:1181-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutthent, R., N. Gaudart, K. Chokpaibulkit, N. Tanliang, C. Kanoksinsombath, and P. Chaisilwatana. 2003. p24 antigen detection assay modified with a booster step for diagnosis and monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1016-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]