Abstract

The development of analytical methods for parallel characterization of multiple phytoconstituents is essential to advance the quality control of herbal products. While chemical standardization is commonly carried out by targeted analysis using gas or liquid chromatography-based methods, more universal approaches based on quantitative 1H NMR (qHNMR) measurements are being used increasingly in the multi-targeted assessment of these complex mixtures. The present study describes the development of a 1D qHNMR-based method for simultaneous identification and quantification of green tea constituents. This approach utilizes computer-assisted 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA) and enables rapid profiling of seven catechins in commercial green tea extracts. The qHNMR results were cross-validated against quantitative profiles obtained with an orthogonal LC-MS/MS method. The relative strengths and weaknesses of both approaches are discussed, with special emphasis on the role of identical reference standards in qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Keywords: Green tea catechins, qNMR, qHNMR, 1H NMR fingerprints, HiFSA, LC-MS/MS

1. Introduction

Standardization is a fundamental practice to guarantee the quality and consistency of botanical preparations used as dietary supplements and health products [1,2]. This process involves the selection of one or more phytoconstituents as suitable chemical and/or biological markers for the specific plant species, followed by the detection and quantification of the selected markers using validated analytical methods. Although the choice of an appropriate analytical method depends largely on the specific chemical properties of the selected constituents, the quality control of herbal products is commonly carried out by gas or liquid chromatographic separation combined with sensitive detection by mass spectrometry (MS) or UV-visible spectrophotometry (UV/vis) [3–5]. In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the direct application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques for the analysis of complex mixtures [6], thereby bypassing the separation effort required in traditional chromatography-based methods. Major progress has been made over the past decade in developing quantitative NMR (qNMR) methods for both metabolomics and natural product research [7,8], and this knowledge can now be applied to the analysis and quality control of herbal products as well.

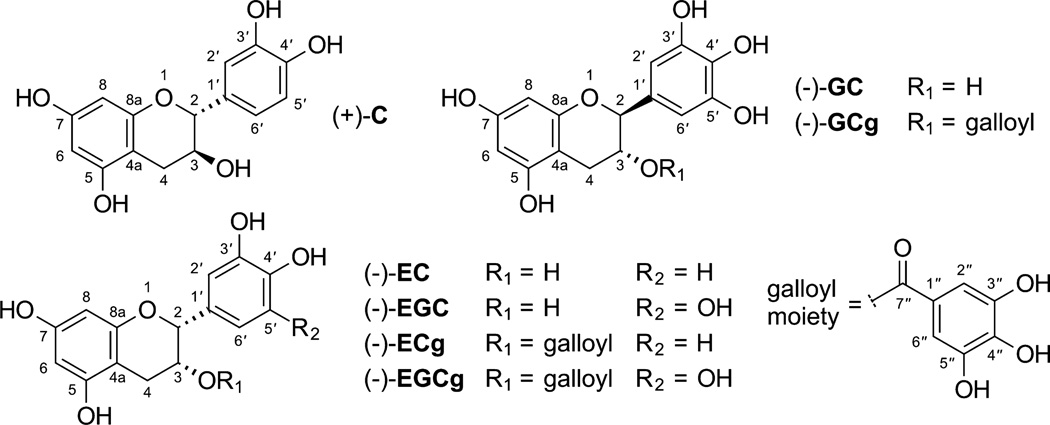

This report describes the development and application of an efficient qNMR method for the simultaneous analysis of seven chemical markers in crude extracts of green tea, produced by non-fermented leaves of Camellia sinensis (L) Kuntze. The green tea phytoconstituents selected for this study (Fig. 1) comprise seven catechins known for their antioxidant properties. The major catechins found in green tea products are (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCg), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin-3-O-gallate (ECg), and (−)-epicatechin (EC). Other polyphenols such as (+)-catechin (C), (−)-gallocatechin (GC), and (−)-gallocatechin-3-O-gallate (GCg) are also present, although in smaller quantities.

Fig. 1.

Structures of the green tea markers selected for this study (C: catechin; EC: epicatechin; EGC: epigallocatechin; ECg: epicatechin-3-O-gallate; EGCg: epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate; GC: gallocatechin; GCg: gallocatechin-3-O-gallate).

Given the social, cultural, and economic importance of green tea, along with its many recognized health benefits [9], numerous analytical methods have been developed for the quality assessment of green tea products. As expected, the majority of these methods involve targeted analysis by LC-UV/vis or LC-MS techniques [10–13]. Several studies on the 1H NMR-based analysis of green tea have been described [14–18], although all of them focused on the application of 1H NMR and multivariate statistical analysis to establish compositional differences between numerous (as many as two hundred) green tea samples. Chemometric approaches enabled efficient distinction between products of different geographical origin [14,15] or quality [16], and have correlated the relative content of the markers with growing or harvesting conditions [17,18]. Still, the application of quantitative 1H (qHNMR) measurements for the absolute quantification of multiple phytoconstituents in green tea samples has not been fully explored.

The present study combines a recently validated qHNMR method, specifically developed for the analysis of natural products [19], with a computational approach called 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA) [20], which enables the unequivocal identification of individual phytoconstituents in complex green tea samples. The computer-aided HiFSA method involves (i) the development of characteristic 1H NMR profiles (NMR fingerprints) of the seven marker compounds, and (ii) the subsequent identification and quantification of these markers in complex mixtures using their NMR fingerprints. The tandem qHNMR/HiFSA method was tested by evaluating a standardized green tea extract reference material, as well as two commercially available green tea extracts. In addition, the outcome of the qHNMR analysis was compared to the results obtained by a more traditional and orthogonal approach using LC-MS/MS.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Purified green tea constituents and naringenin, the latter used as internal standard for LC–MS/MS analysis, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA), ChromaDex Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA), and Indofine Chemical Company Inc. (Hillsborough, NJ, USA). The standardized green tea extract reference material (SRM 3255) was purchased from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, Gaithersburg, MD). Polyphenol-enriched green tea extracts were kindly provided by Naturex Inc. (South Hackensack, NJ, USA). Hexadeuterodimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6, D 99.9%) was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. (Andover, MA, USA). The dimethyl sulfone (DMSO2) standard for qHNMR analysis (TraceCERT-certified reference material) was purchased from Fluka Analytical, part of the Sigma–Aldrich group. Organic solvents and water for LC–MS/MS analysis were purchased from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). All commercially available materials were used as received without further purification.

2.2. NMR spectroscopy

Samples for NMR fingerprinting of individual green tea constituents were prepared by precisely weighing 0.5–6 mg (±0.01 mg) of analytes using a XS105 Dual Range analytical balance (Mettler Toledo Inc., Toledo, OH, USA). The analytes were weighed directly into standard 5-mm NMR tubes (XR-55 series) purchased from Norell Inc. (Landisville, NJ, USA). A total of 600 µL of DMSO-d6 was then added to the NMR tubes using a Pressure-Lok gas syringe from VICI Precision Sampling Inc. (Baton Rouge, LA, USA). The samples were prepared at the following concentrations (in mg/mL): C: 6.32; EC: 4.78; GC: 0.80; EGC: 2.63; ECg: 2.68; GCg: 0.67; and EGCg: 3.13. For the quantitative analysis of each green tea extract, three independent samples were prepared by precisely weighing 10–12 mg (±0.01 mg), adding 600µLof a freshly prepared 2.5 mM (approx. 0.25 mg/mL) solution of DMSO2 in DMSO-d6, and transferring 550 (µL to the NMR tube.

NMR measurements were performed at 600.13 and 899.94 MHz (1H frequency) on Bruker AVANCE and AVANCE II spectrometers equipped with 5-mm TXI and TCI inverse detection cryoprobes, respectively. All NMR experiments were recorded at 298 K (25°C) without sample spinning, and the probes were frequency tuned and impedance matched prior to each experiment. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million (ppm) with reference to the TMS scale. Scalar coupling constants (J) and effective linewidths (Δv1/2) are given in Hertz (Hz).

High-resolution 1H NMR spectra were recorded under quantitative conditions using a 90° pulse experiment. The 90° pulse width (pw90) was optimized for each sample by determining the null at 360° (pw360) and applying the equation pw90 = ¼ ×pw360. The following acquisition parameters were used: a spectral window of 30 ppm (centered at 7.5 ppm), an acquisition time of 4.0 s, and a relaxation delay of 60 s. This long relaxation delay represents more than five times the longest T1 value measured within any of the spectra. For NMR experiments recorded at 900 MHz, at least 8 transients were collected with 216,798 total data points, and a fixed receiver gain of 64. NMR experiments at 600 MHz were recorded with 64 transients, 143,882 total data points, and a fixed receiver gain of 16. The total accumulation time per sample in quantitative experiments was 68 min.

The 1H NMR data were processed with TopSpin software (v.3.2, Bruker BioSpin Inc.) using a Lorentzian-Gaussian window function for resolution enhancement (line broadening = −0.3, Gaussian factor = 0.05). Prior to Fourier transformation, zero filling was applied to increase the number of data points to 256k and 1024k in experiments recorded at 600 and 900 MHz, respectively. The digital resolution after zero filling was 0.069 Hz/pt at 600 MHz, and 0.026 Hz/pt at 900 MHz. All the NMR spectra were manually phased, referenced to the residual protonated solvent signal (DMSO-d5, δ = 2.500 ppm), and baseline corrected using polynomial functions.

2.3. Computer-aided NMR spectral analysis

Comprehensive 1H NMR profiles of the seven green tea chemical markers in DMSO-d6 were generated with PERCH NMR software (v.2011.1, PERCH Solutions Ltd.) using the Automated Consistency Analysis (ACA) module [21]. Molecular 3D models of the green tea catechins were built with Maestro software (v.9.0.211, Schrodinger, LLC.) using the X-ray crystal structure of (−)-EGCg (bound to V30M transthyretin, protein data bank id: 3NG5) as a template. The 3D molecular models and the processed NMR data (in MDL Molfile and Bruker 1r format, respectively) were imported into PERCH’s ACA module, which performed the complete spectral analysis largely in automation. This process includes peak picking, integration, conformational analysis, and prediction of basic NMR parameters (all δ, J, and Δv½ values). In addition, ACA automatically detects and fits the resonances of residual DMSO-d5, water, and TMS.

Next, ACA evaluated potential solutions (i.e., sets of probable 1H NMR assignments) by matching and refining the predicted NMR parameters of each solution against the experimental 1H NMR data using Quantum-Mechanical Total Line Shape (QMTLS) iterators. The optimization of calculated NMR parameters was carried out by ACA using the following 3-step protocol: (i) analysis of discrete spin systems using the D-mode; (ii) evaluation of the complete 1H NMR spectrum using the T-mode; and (iii) optimization of Gaussian and dispersion contributions to the line shape, also using the T-mode. In those cases where ACA was unable to find a consistent solution, that is, excellent fit as well as δ,J, and Δv1/2 values consistent with the molecular structure, the predicted NMR parameters were adjusted manually using the ACA graphical user interface (ACA-GUI), and the iterative process was repeated until convergence was reached (root-mean squared deviation, rmsd <0.1%). The 1H NMR profiles of the green tea chemical markers in DMSO-d6 were stored in individual PERCH parameters (.pms) files, which contain the optimized δ, J, and Δv1/2 values (see Supplementary data).

For the evaluation of mixtures, 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA) was carried out manually using the PERCH shell. The processed 1H NMR spectra of the mixtures were imported into PERCH using the IMP module. Peak picking and integration were carried out with the PAC module. The 1H NMR profiles of the seven catechins and DMSO2 (singlet at δ = 3.000 ppm) were combined into a single PERCH .pms file using Notepad++ software (v.5.9.6.2, http://notepad-plus-plus.org/). The resulting .pms file (see Supplementary data) was imported into PERCH’s PMS module, and a simulated lH NMR spectrum of an equimolar mixture of the seven catechins plus DMSO2 was automatically generated. Spectral regions free of 1H resonances belonging to the selected markers were omitted (“masked”) for the iterative analysis. The downfield, broad signals belonging to exchangeable protons (δ = 7.5–9.5 ppm) were also excluded from the quantitative analysis. The calculated parameters were fitted to the experimental 1H NMR spectra of the mixtures using the PER module, and honed using the T-mode with Gaussian and dispersion optimization until convergence was reached. To avoid the distortion of predicted 1H NMR signals, the optimized J values were kept constant (“fixed”). The iteration process was repeated until the calculated NMR fingerprint matched the overall signal profile and intensity of the observed 1H NMR spectrum. After the iterative analysis was completed, only minor differences between the initial and optimized chemical shift values were observed (Δδ ≤ 10 ppb). The relative molar concentrations of the seven catechins and DMSO2 were automatically calculated by PERCH as part of the iterative optimization process. These values were transferred to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for further analysis. Absolute content by qHNMR was calculated using the DMSO2 signal (equivalent to six hydrogen nuclei) as internal calibrant.

2.4. LC-MS/MS analysis

Chromatographic analysis was carried out with a Shimadzu LC-20A series HPLC system equipped with an online solvent degasser unit, two dual-plunger parallel-flow pumps, a refrigerated autosampler, and a column oven set to 40°C. Separation was achieved on an XTerra MS C18 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm i.d., 2.5 µm) from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA, USA), using mixtures of solutions A (0.1% of formic acid in water) and B (0.1% of formic acid in acetonitrile) as mobile phase. The amount of solution B in the mobile phase (expressed as % v/v) was linearly increased from 5% to 15% during the first 8 min, followed by a second linear increase to 95% B from 8 to 10 min. The composition of the mobile phase was kept constant at 95% B for 2 min, and then returned to the initial conditions in 1 min. To ensure equilibration, a post-run time of 4 min at 5% B was defined. The total chromatographic analysis time per sample was 17 min. Samples were analyzed with an injection volume of 10 µL, and a constant flow rate of 300 µL/min.

MS/MS data were recorded with an Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex 4000 QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Concord, ON, Canada) equipped with a Turbo V ion source, operating in electrospray ionization (ESI) positive ion mode using a TurboIonSpray probe. The following source parameters were used: IonSpray voltage 4800 V; probe temperature 500°C; nebulizer gas (N2) 50 psi; turbo gas (N2) 50 psi; curtain gas (N2) 30 psi; entrance potential 9.2 V. Experiments were carried out in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) scan mode. Precursor ions were selected in the first quadrupole (Ql), and product ions were generated by collision induced dissociation (CID) in the linear accelerator collision cell (second quadrupole, Q2). Next, product ions were filtered, trapped, and scanned in the third quadrupole (Q3), operating as a linear ion trap. Both the Q1 and Q3 quadrupoles operated at unit resolution. The declustering potentials (DP), collision energies (CE), and collision cell exit potentials (CXP) were optimized for each analyte in infusion experiments performed as follows: dilute solutions (2.0 µg/mL) of the individual compounds in a mixture of methanol and water (1:1, v/v) were infused into the mass spectrometer at a constant flow rate of 10 µL/min using a Fisher Scientific single syringe pump. The criteria for identification of individual green tea markers in LC-MS/MS experiments included their chromatographic retention times (tR) and characteristic MRM transitions (Table 1). System control and LC-MS/MS data analysis were carried out with Analyst software (v.1.5.2, AB Sciex Pte. Ltd.). For quantitative analysis, the extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) were saved as individual text (.txt) files and imported into Fityk software (v.0.9.1, http://fityk.nieto.pl). Peak areas were determined by least-squares fitting of the chromatographic peaks to Gaussian functions using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. These values were transferred to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for further analysis.

Table 1.

Identification of green tea catechins by LC-MS/MS: molecular weight, chromatographic retention times, and MRM transitions (in positive ion mode) of the studied markers.

| Compound | MW | tR [min] | MRM transition [m/z] |

|---|---|---|---|

| (+)-C | 290.27 | 3.9 | 291 → 139 |

| (−)-EC | 290.27 | 5.9 | 291 → 139 |

| (−)-GC | 306.27 | 1.7 | 307 → 139 |

| (−)-EGC | 306.27 | 3.5 | 307 → 139 |

| (−)-ECg | 442.37 | 9.2 | 443 → 123 |

| (−)-GCg | 458.37 | 7.3 | 459 → 139 |

| (−)-EGCg | 458.37 | 6.2 | 459 → 139 |

| Naringenin (IS) | 272.26 | 10.7 | 273 → 153 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. NMR fingerprinting of green tea constituents

The definitive identification of the chosen marker compounds is a key step on the quality assessment of herbal products. In the case of 1H NMR, chemical identification denotes the unequivocal recognition of characteristic 1H resonances based on their location and multiplicity. In other words, NMRrequires the determination of accurate δ andJ values to rigorously identify each of the individual phytoconstituents. Although basic NMR parameters of several cat-echins in DMSO-d6 have been described previously [22,23], these reports do not contain all the parameters required to precisely recreate the 1H NMR spectra of the markers selected for this study. Therefore, complete spectral profiles of the seven catechins were generated by 1H iterative Full Spin Analysis (HiFSA) [20]. This computational approach has been applied previously to generate NMR profiles of terpene trilactones and flavonols from Ginkgo biloba [24] as well as flavonolignans from Silybum marianum [25], enabling fast and unambiguous identification of these chemical markers in complex botanical preparations.

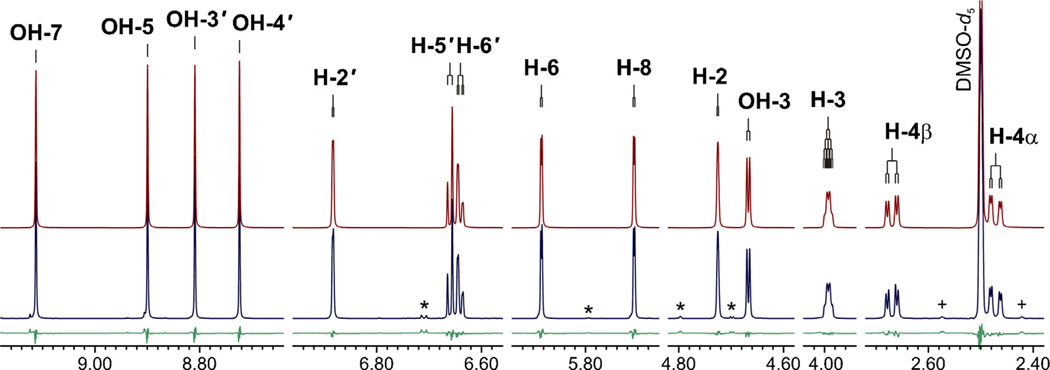

Using an analogous approach, HiFSA led to the comprehensive depiction of the 1H NMR spectra of the selected green tea markers in DMSO-d6. Therefore, all 1H resonances can be described in terms of characteristic δ J, and Δv1/2 parameters, which are summarized in Table 2 and the Supplementary data. In addition, as shown for EC in Fig. 2, HiFSA generated a set of calculated 1H NMR spectra that are essentially identical to the experimental observations (rmsd <0.1%). The high-resolution 1H NMR profiles obtained by HiFSA are made available in easy-to-share text files (see Supplementary data), and will facilitate the rapid identification of each of the seven catechins in DMSO-d6 solution. Furthermore, as will be discussed in the next section, these profiles can be used as “surrogate” reference standards for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of green tea extracts by NMR. This opens a unique opportunity to use primary reference materials as calibrants, which differentiates qHNMRanalysis from traditional chromatography-based standardization methods.

Table 2.

Characteristic 1H NMR profiles of the green tea catechin markers in DMSO-d6 (900 MHz, 298 K), generated by HiFSA.

| δ [ppm], mult. (Jin Hz) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | (+)-C | (−)-EC | (−)-GC | (−)-EGC | (−)-ECg | (−)-GCg | (−)-EGCg |

| H-2 | 4.468, d (7.5) | 4.725, d (1.7) | 4.416, d (7.1) | 4.648, d (1.8) | 5.023, d (1.3) | 5.052, d (5.0) | 4.948, d (1.3) |

| H-3 | 3.805, dddd (5.1, 5.3, 7.5, 8.1) |

3.993, dddd (1.7, 3.7, 4.5, 4.7) |

3.771, dddd (5.0, 5.2, 7.2, 7.7) |

3.974, dddd (1.8, 3.4, 4.3, 4.9) |

5.338, ddd (1.3, 2.4, 4.6) |

5.265, ddd (5.0, 5.0, 5.0) |

5.353, ddd (1.3, 2.4, 4.5) |

| OH-3 | 4.865, d (5.1) | 4.667, d (4.7) | 4.845, d (5.0) | 4.616, d (4.9) | - | - | - |

| H-4α | 2.647, dd (5.3, –16.0) |

2.472, dd (3.7, –16.3) |

2.335, dd (7.7, –15.9) |

2.465, dd (3.4, –16.1) |

2.667, dd (2.4, –17.2) |

2.591, dd (5.0, –16.8) |

2.645, dd (2.4, –17.2) |

| H-4β | 2.341, dd (8.1, –16.0) |

2.669, dd (4.5, –16.3) |

2.597, dd (5.2, –15.9) |

2.658, dd (4.3, –16.1) |

2.926, dd (4.6, –17.2) |

2.564, dd (5.0, –16.8) |

2.918, dd (4.5, –17.2) |

| OH-5 | 8.938, s | 8.899, s | 8.930, s | 8.894, s | 8.910, s | 8.959, s | 8.914, s |

| H-6 | 5.881, d (2.3) | 5.884, d (2.3) | 5.874, d (2.3) | 5.878, d (2.3) | 5.929, d (2.3) | 5.919, d (2.3) | 5.925, d (2.3) |

| OH-7 | 9.179, s | 9.113, s | 9.159, s | 9.102, s | 9.045, s | 9.076, s | 9.044, s |

| H-8 | 5.678, d (2.3) | 5.707, d (2.3) | 5.681, d (2.3) | 5.702, d (2.3) | 5.821, d (2.3) | 5.817, d (2.3) | 5.819, d (2.3) |

| H-2′ | 6.713, dd (0.2, 2.1) | 6.884, dd (0.3, 2.0) | 6.237, d (1.9) | 6.366, d (1.9) | 6.846, dd (0.3, 2.1) | 6.255, d (1.9) | 6.394, d (1.9) |

| OH-3′ | 8.866, s | 8.809, s | 8.773, s | 8.706, s | 8.870, s | 8.858, s | 8.717, s |

| OH-4′ | 8.818, s | 8.724, s | 8.020, s | 7.951, s | 8.769, s | 8.102, s | 8.034, s |

| H-5′ | 6.677, dd (0.2, 8.0) | 6.659, dd (0.3, 8.1) | - | - | 6.645, dd (0.3, 8.2) | - | - |

| OH-5′ | - | - | 8.773, s | 8.706, s | - | 8.858, s | 8.717, s |

| H-6′ | 6.587, dd (2.1, 8.0) | 6.641, dd (2.0, 8.1) | 6.237, d (1.9) | 6.366, d (1.9) | 6.743, dd (2.1, 8.2) | 6.255, d (1.9) | 6.394, d (1.9) |

| H-2″ | - | - | - | - | 6.813, d (1.6) | 6.852, d (1.6) | 6.807, d (1.6) |

| OH-3″ | - | - | - | - | 9.238, s | 9.268, s | 9.197, s |

| OH-4″ | - | - | - | - | 9.299, s | 9.312, s | 9.289, s |

| OH-5″ | - | - | - | - | 9.238, s | 9.268, s | 9.197, s |

| H-6″ | - | - | - | - | 6.813, d (1.6) | 6.852, d (1.6) | 6.807, d (1.6) |

Fig. 2.

The 1H NMR fingerprint of EC as an example of the HiFSA fingerprinting process. Comparison between the calculated (red, top trace) and experimental (blue, middle trace) 1 H NMR spectra of EC in DMSO-d6 (900 MHz, 298 K). Residuals are shown in green (bottom trace). The asterisk (*) denotes signals due to impurities. (+) denotes the 13 C satellites of the DMSO-d5 resonance. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Quantitative 1H NMR analysis

One of the challenges in analyzing complex mixtures by 1D 1H NMR is overcoming spectral overlap problems frequently encountered in the narrow 1H chemical shift window. These problems are especially observed in mixtures of structurally related compounds such as the green tea catechins because, as shown in Table 2, common structural motifs exhibit similar NMR signal patterns. This situation might be aggravated in botanical products by the occurrence of related and/or unrelated chemical constituents with coincident δ values. As a result, the unambiguous identification of characteristic 1H NMR signals, even if they are partially obscured by other 1H resonances, becomes crucial in the qHNMR analysis of mixtures.

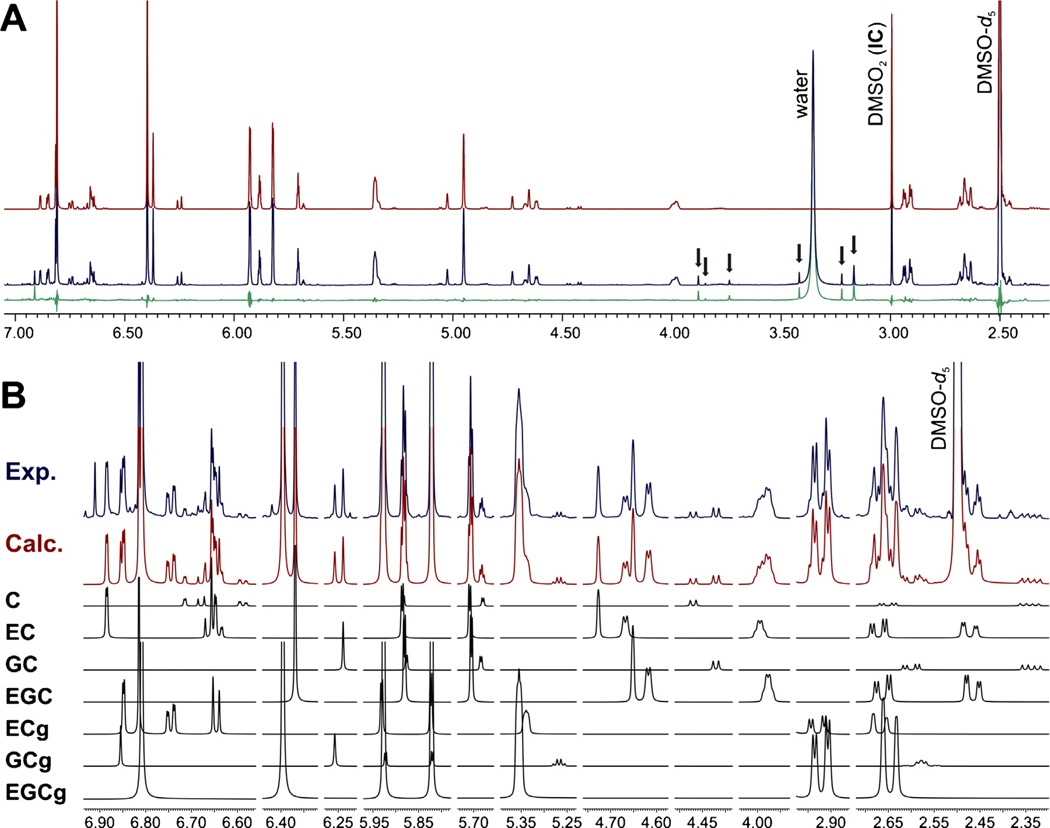

The characteristic HiFSA profiles generated in this study enabled a rapid identification of the seven catechins in green tea extracts. Under quantitative conditions, the integrals of all the 1H NMR signals of a given marker are directly proportional to the relative number of nuclei giving rise to these signals. Similarly, the integration areas of 1H NMR signals belonging to two or more markers will reflect the relative molar proportions of the chemical components involved. Therefore, complex NMR signal patterns arising from extensive spectral overlap can be interpreted as a linear combination of multiple 1H resonances, and the overall shape and intensity of such patterns encode the molar ratio between the respective mixture constituents.The semi-automated, iterative calculations carried out with PERCH, combined with the application of 1H NMR fingerprints as “surrogate” reference materials, guarantees a synchronized examination of the overall signal profile in the 1D 1H NMR spectra of green tea extracts. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3, this thorough analysis revealed the contribution (i.e., the intensity response) of each of the chosen markers to the observed 1H NMR signal patterns. As a net result, the relative molar content of all seven catechins in green tea extracts was determined simultaneously.

Fig. 3.

(A) Comparison between the experimental 1H NMR spectrum (blue, top trace) of the green tea extract GT1 in DMSO-d6 (600 MHz, 298 K) and the HiFSA-generated spectrum corresponding to the studied markers (red, 2nd trace from top). Residuals are shown in green, and arrows indicate NMR signals belonging to methylated xanthines. (B) Sections of the experimental (blue) and calculated (red)spectraof GT1, including intensity-adjusted fingerprints (black, the seven lowertraces marked with the compounds abbreviations) of the seven catechins selected as markers. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Absolute value qHNMR measurements were carried out by using dimethyl sulfone (DMSO2) as internal calibrant (IC). This compound has been proposed as a universal reference standard for qHNMR analysis [26], and was selected as IC for this study because of its chemical stability and high solubility in DMSO-d6. Moreover, DMSO2 is commercially available as a highly pure, well-characterized substance, and its sole 1H resonance is a singlet located in a clear region of the 1H NMR spectra of green tea extracts (Fig. 3).

To test the suitability of the qHNMR/HiFSA tandem approach for multi-targeted standardization of green tea products, this methodology was applied to the analysis of an NIST-certified, green tea extract standard reference material (SRM 3255) [27]. This material is part of a growing series of reference standards developed by NIST for the analysis of botanical dietary supplements and food ingredients [28–31]. SRM 3255 was developed to assist in the validation of new analytical methods for the determination of catechins and methylated xanthines in green tea extracts. The Certificate of Analysis (CofA) of SRM 3255 is available online and free of charge at http://www.nist.gov/srm. The CofA states the amount of individual catechins in SRM 3255 as an equally weighted mean of results obtained by established LC-UV and LC-MS methods in several collaborating laboratories. These certified values, expressed as mass fractions, are summarized in Table 3, along with the results obtained by the newly developed qHNMR methodology.

Table 3.

Certified content of the NIST green tea extract standard reference material, SRM 3255, compared to the results obtained by orthogonal qHNMR and LC-MS/MS analyses (in mg/g).

| Compound | Certificate of analysis, mass fraction | qHNMR/HiFSA, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) | LC-MS/MS, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (+)-C | 9.17 ± 0.93 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 10.5 ± 0.6 |

| (−)-EC | 47.3 ± 6.7 | 43.6 ± 0.7 | 45.3 ± 2.2 |

| (−)-GC | 22.0 ± 1.7 | 20.2 ± 0.4 | 21.4 ± 1.1 |

| (−)-EGC | 81.8 ± 6.5 | 77.0 ± 1.5 | 76.0 ± 6.1 |

| (−)-ECg | 100.3 ± 7.8 | 111.9 ± 2.2 | 109.7 ± 7.1 |

| (−)-GCg | 39.0 ± 2.0 | 44.0 ± 0.8 | 41.0 ± 2.3 |

| (−)-EGCg | 422.0 ± 19.0 | 424.7 ± 6.4 | 417.9 ± 11.2 |

The qHNMR outcome is fairly consistent with the values reported in the CofA, although relative deviations in the order of 10% were observed for C, ECg, and GCg. These differences may be caused by curve-fitting errors during the iterative analysis. In this study, HiFSA targets seven markers in a complex botanical sample, and although these markers amount to 65–75% in weight (w/w) of green tea extracts, the presence of additional phytoconstituents certainly affects the overall NMR signal pattern. The parallel analysis of multiple 1H resonances of each marker is intended to minimize the effects of signal overlap and, in some cases, will reveal the occurrence of other resonances with coincident δ values (see residuals in Fig. 3). The qHNMR/HiFSA tandem approach showed high precision in the determination of catechin concentrations, with coefficients of variation (i.e., relative standard deviations) of less than 2%. These observations not only demonstrate the high precision of qNMR measurements but also the reproducibility and reliability of the computer-aided iterative analysis. Still, considering the differences between the certified values and the qHNMR results, the content of the seven markers was determined by an orthogonal LC-MS/MS method, which showed congruence with the qNMR outcome and will be discussed in the following section.

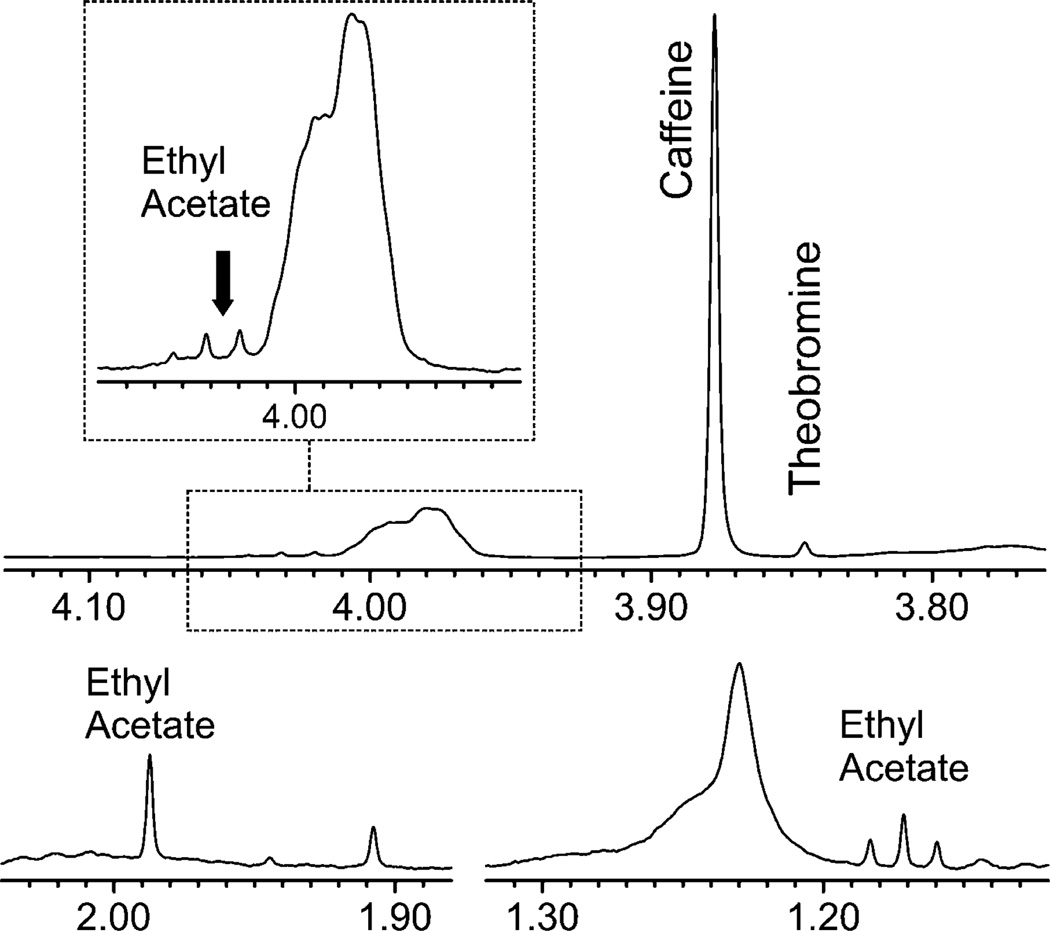

Although HiFSA facilitates the targeted analysis of the seven catechins selected as chemical markers, the untargeted nature of 1H NMR detection also enables the analysis of additional mixture constituents. Specifically, the content of the two methylated xanthines, caffeine and theobromine, was assessed as being 33.6 and 0.778 mg/g, respectively, and found to be in accordance with the mass fraction values reported in the CofA (36.9 and 0.867 mg/g, respectively). In addition, a small amount of residual ethyl acetate from the extraction process (<0.05%, w/w) was measured (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Sections of the 1H NMR spectrum of the standardized green tea extract SRM 3255 in DMSO-d6 (600 MHz, 298 K) demonstrate how qHNMR can readily detect and quantify additional phytoconstituents such as caffeine and theobromine, as well as residual organic solvents such as ethyl acetate.

Two commercially available green tea extracts, GT1 and GT2, were also evaluated by qHNMR and HiFSA fingerprinting. The 1H NMR spectra of both extracts exhibited signal patterns similar to those observed during the analysis of SRM 3255, thereby confirming that GT1 and GT2 are polyphenol-rich green tea extracts. However, the outcome of the quantitative analysis, summarized in Table 4, showed that the polyphenol content of both extracts is significantly different (P < 0.05), as are the relative proportions between the selected chemical markers in both materials. For example, the amount of EGCg in GT1 is more than 7% (w/w) higher than that in GT2. Substantial differences in the amount of GC and GCg were also observed, with higher concentrations of both compounds in GT2. Moreover, variations in the content of methylated xanthines and residual ethyl acetate were detected (see Supplementary data). Overall, these experiments demonstrated the suitability of this methodology for rapid qualitative and quantitative profiling of phytoconstituents and potential impurities in green tea products.

Table 4.

Content of seven catechins in commercial extracts GT1 and GT2, as determined by orthogonal qHNMR and LC-MS/MS methods (in mg/g).

| Compound | GT1 |

GT2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qHNMR/HiFSA, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) | LC-MS/MS, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) | qHNMR/HiFSA, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) | LC-MS/MS, mean ± S.D. (n = 3) | |

| (+)-C | 9.71 ± 0.19 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 8.94 ± 0.16 | 9.87 ± 0.83 |

| (−)-EC | 53.7 ± 0.9 | 51.6 ±3.3 | 52.5 ± 0.9 | 54. 3 ± 2.4 |

| (−)-GC | 14.5 ± 0.2 | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 28.6 ± 0.4 | 26.0 ± 1.3 |

| (−)-EGC | 88.7 ± 1.7 | 93.3 ± 3.4 | 94.7 ± 1.7 | 95.5 ± 6.7 |

| (−)-ECg | 95.6 ± 1.7 | 92.9 ± 4.8 | 91.6 ± 1.7 | 90.3 ± 5.5 |

| (−)-GCg | 18.0 ±0.3 | 18.4 ± 1.7 | 28.0 ± 0.6 | 29.1 ± 1.5 |

| (−)-EGCg | 458.0 ± 7.8 | 450.1 ± 11.1 | 386.2 ± 6.3 | 397.3 ± 12.0 |

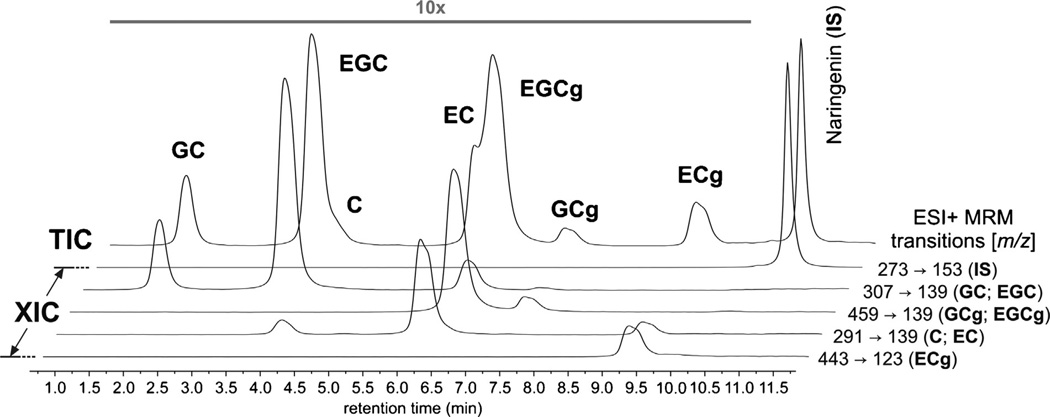

3.3. Comparison with LC-MS/MS results

In order to test the validity of the qHNMR results, an LC-MS/MS method for determination of catechins in green tea extracts was developed in-house. The analysis of the green tea extracts by an alternative and orthogonal method offers an additional level of evidence. Furthermore, the comparison of analytical methods provides insight into potential sources of error when disagreement occurs. As a prerequisite for the development of the LC-MS/MS method, a reliable procedure for chromatographic analysis of the seven catechins was established (Fig. 5). MS detection was performed in MRM scan mode, which provided both high sensitivity and selectivity. Naringenin was selected as internal standard (IS) for LC-MS/MS analysis because of its structural similarity to the green tea catechins, as well as its commercial availability in multi-gram quantities and good quality. Calibration curves were generated using nine concentrations of each analyte. Based on the qHNMR results, EGCg and ECg were assessed at concentrations of 0.1–50 µg/mL, whereas the remaining markers were evaluated at lower concentrations over the range of 0.05–20 µg/mL. Clear linear trends were obtained for all the calibration curves, with coefficient of determination (R2) greater than 0.995 in all cases (see Supplementary data). The green tea extracts SRM 3255, GT1, and GT2 were analyzed in triplicate at a concentration of 20 µg/mL. All samples and calibrants were run consecutively, for a total analysis time of 28 h.

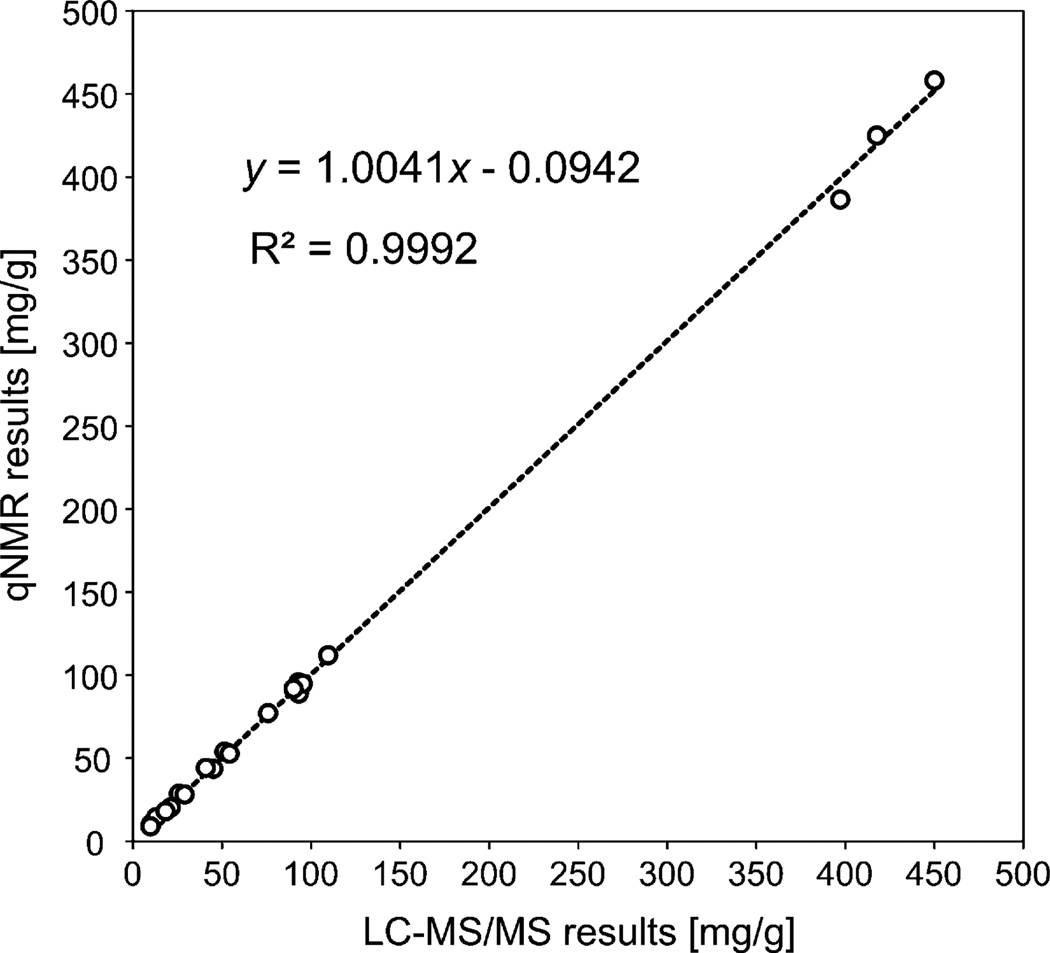

Fig. 5.

Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the green tea extract GT2 (black) and extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) for characteristic MRM transitions of the studied green tea catechins (blue).

The results of the LC-MS/MS analysis of SRM 3255, summarized in Table 3, are consistent with those obtained by qHNMR, thereby cross-validating the two analytical approaches. However, substantial differences in the precision of both methods were observed. While the qHNMR/HiFSA results varied within a margin of ±2%, the LC-MS/MS outcome exhibited coefficients of variation of up to 8–10%. Although this level of error might be considered to be high, it is fairly acceptable for the multi-targeted analysis of botanical preparations by LC-MS/MS [32,33], especially taking into account the chemical complexity of these materials, as well as the very limited information available on the composition of commercial herbal products. The differences in precision between the two methods were also observed during the analysis of GT1 and GT2 (Table 4). Nevertheless, both methods clearly reflected the differences in chemical composition between the two commercial extracts, and relatively minor variations in the measured content of selected phytoconstituent were observed (≤10% relative difference between qHNMR and LC-MS/MS results). The two analytical methods were further compared by plotting the catechin concentrations obtained by qHNMR against the concentration values measured by LC-MS/MS. The linear regression showed an excellent correlation (R2 > 0.999) with a slope value close to unity and an intercept close to zero (Fig. 6), thereby demonstrating the agreement between the two orthogonal approaches. Still, in order to understand the differences observed between the two methods, especially in terms of precision, it is important to analyze potential sources of variability that could affect the analytical results.

Fig. 6.

Congruence between the concentrations of the studied catechins in green tea extracts as determined by orthogonal qHNMR and LC-MS/MS methods.

The differences between the qHNMR and LC-MS/MS methods described in this report extend far beyond the fact that both techniques detect different physical phenomena. Important differences in crucial experimental steps such as method development, sample preparation, and calibration have practical implications and, therefore, need to be discussed.

The application of LC-based methods for quantitative purposes requires the optimization of chromatographic conditions to minimize potential interferences due to peak overlap. Although some chemical markers exhibited similar retention times in our chromatographic system, the analysis of characteristic fragmentation transitions using the MRM scan mode enabled the distinction of co-eluting constituents (Fig. 5). Still, as the selected chemical markers include several pairs of diastereomers with the same MRM transitions, the unequivocal identification of the individual chemical markers relied on the availability of identical reference materials and their subsequent analysis under the same chromatographic conditions.

For 1D qHNMR analysis, the lack of separation steps and the limited chemical shift dispersion may often result in the observation of crowded spectral regions and severe signal overlap. The selection of an appropriate deuterated solvent might help improve the signal dispersion in particular regions of the NMR spectrum, but it is unlikely to resolve the overlap problem, especially in complex mixtures such as botanical extracts. The targeted analysis of all 1H resonances belonging to the selected markers using HiFSA profiles represents a reliable strategy for chemical identification, and provides a unique level of specificity for qHNMR analysis. Notably, this approach only requires small quantities of the reference materials to build the profiles. In addition, once the HiFSA profiles are generated, they can be used as surrogate standards for all future qHNMR analyses. As a result, these digital 1H NMR profiles eliminate the need for pure phytochemicals during the identification process. Of course, a new set of HiFSA profiles must be generated if the analysis is carried out in a different deuterated solvent.

Sample requirement and the sample preparation procedures represent significant differences between qHNMR and LC-MS/MS methods. In general, sample preparation for qHNMR analysis is a reasonably simple process. The selection of the deuterated solvent depends largely on the solubility of the sample and the dispersion of the resulting 1H NMR spectrum. Samples for HiFSA fingerprinting require only small quantities of the pure phytoconstituents, and only need to be run once.To minimize the impact of weighing errors during the qHNMR analysis, dry gravimetric samples need to be prepared by carefully weighing around 10 mg of the sample extract. Importantly, NMR analysis minimizes sample handling. There is only one dilution step for the preparation of the internal calibrant (IC) solution, and one volumetric transfer to mix the IC and the sample. On the other hand, samples for LC-MS/MS analysis must be filtered and subjected to several dilution and transfer steps to reach the low concentrations needed for analytical-scale HPLC separation and MS detection. The more complex sample handling and preparation may be associated with the lower precision of the LC-MS/MS method, and may limit the achievable precision of multi-targeted analysis.

The calibration differences between the qNMR and LC-MS/MS methods are also noteworthy. Because each of the selected markers shows a distinct analytical response, LC-MS/MS requires the generation of individual calibration curves and the use of identical reference materials. Therefore, the quantitative results achieved by LC-MS/MS not only depend on the availability of often rare phytochemicals, but also on their chemical stability and purity. Moreover, in our experience, stock solutions must be freshly prepared before each new set of experiments, and the generation of a concentration series involves numerous dilution and transfer steps, which leads to more potential errors. In addition, a structurally related compound, such as naringenin in the present case, is required as internal standard (IS) to control the ionization variability. The use of an IS minimizes the effect of inconsistencies during LC injection and other experimental variables such as the effect of solvent evaporation during sample storage in the autosampler. At the same time, the use of an IS implies that this substance must be considered also during the optimization of chromatographic conditions, which further increases the demand on the suitability of the multi-targeted chromatographic method. For example, because of its lower polarity, naringenin has a longer chromatographic retention than the green tea catechins (Fig. 5), and the proportion of the organic solution B in the mobile phase had to be increased to 95% (v/v) to ensure elution of this compound. In the case of qHNMR, the direct proportionality between its analytical response and the molar concentrations of all proton-bearing molecules facilitates the calibration process, and a sole internal calibrant is required. Contrary to LC-MS/MS, the IC for qNMR analysis (in this case, DMSO2) is not structurally related to the analytes, and was selected because its 1H resonance does not overlap with any of those corresponding to the green tea constituents. In order to preserve these practical advantages of internal calibration in qHNMR, particular attention must be paid to the preparation of the IC solution, as any errors will equally affect the measurements of all target markers.

4. Conclusions

This report introduces two orthogonal analytical approaches for the determination of seven catechin markers in green tea extracts. The first approach combines qHNMR measurements with targeted HiFSA, a reliable computational methodology for the rapid identification of the selected markers. The qHNMR/HiFSA tandem enables simultaneous identification and quantification of the seven catechins. Furthermore, the interpretation of characteristic resonance patterns in the 1D 1H NMR spectra of green tea extracts provides evidence of the authenticity of these complex, nature-derived materials by simple visual inspection. This approach also exploits the abundant structural information contained in 1H NMR spectra. Moreover, it allows for the quantification of additional phytoconstituents and potential impurities without the need for identical reference materials. For example, the qHNMR/HiFSA method could be applied to establish compositional differences between regular and decaffeinated green tea products.

The second approach involves the use of a more traditional analysis by LC-MS/MS, which provided data for cross-validation of the two orthogonal analytical methods (qHNMR⊥ LC-MS/MS). Reliable chromatographic conditions were developed, and characteristic retention times and MRM transitions were used to identify and target the seven markers. The results obtained by both approaches were compared and confirmed that the two orthogonal methods show reasonable agreement in the determination of catechins in green tea materials, including a NIST-certified reference standard material. This study demonstrates that the qHNMR/HiFSA tandem approach represents a fast, reliable, and affordable alternative to chromatographic methods for the quality assessment of green tea products. The increasing availability of NMR instrumentation equipped with superconducting magnets adds to this positive prospect.

From both a practical and an analytical perspective, this study demonstrated that qHNMR is a very capable technology which holds promise for the multi-targeted standardization of botanical products. One particularly attractive feature is its capability to work with digital profiles as reference materials, and to substitute costly and rare calibrants with easily accessible standards such as DMSO2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are particularly grateful to Matthias Niemitz and Dr. Samuli-Petrus Korhonen of PERCH Solutions Ltd., Kuopio (Finland), for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions on the computational analysis of pure compounds and complex mixtures using PERCH. We thank Drs. Kim Colson and Joshua Hicks, as well as Ms. Sarah Luchsinger (Bruker Biospin) for helpful discussions and feedback on qHNMR method development. We also thank our colleague, Maiara da Silva Santos, for helpful discussion during the preparation of this manuscript, and Dr. Benjamin Ramirez for his valuable assistance in the NMR facility at the UIC Center for Structural Biology (CSB). The present work was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through grant RC2 AT005899, awarded to Dr. Guido F. Pauli by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Dr. Jose G. Napolitano was supported by the United States Pharmacopeial Convention as part of the 2012/2013 USP Global Research Fellowship Program. The purchase of the 900-MHz NMR spectrometer and the construction of the CSB were funded by the NIH grant P41 GM068944, awarded to Dr. Peter G.W. Gettins by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2013.06.017.

References

- 1.van Breemen RB, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR. The role of quality assurance and standardization in the safety of botanical dietary supplements. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:577–582. doi: 10.1021/tx7000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu PP, Chiang H-M, Xia Q, Chen T, Chen BH, Yin J-J, Wen K-C, Lin G, Yu H. Quality assurance and safety of herbal dietary supplements. J. Environ. Sci. Health C. 2009;27:91–119. doi: 10.1080/10590500902885676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong ES. Extraction methods and chemical standardization of botanicals and herbal preparations. J. Chromatogr. B. 2004;812:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng JG, Tan M-L, Peng X, Luo Q. Standardization and quality control of herbal extracts and products. In: Liu WJH, editor. Traditional Herbal Medicine Research Methods. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2011. pp. 377–427. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu L, Hao H, Wang G. LC/MS based tools and strategies on qualitative and quantitative analysis of herbal components in complex matrixes. Curr. Drug Metab. 2012;13:1251–1265. doi: 10.2174/138920012803341285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novoa-Carballal R, Fernandez-Megia E, Jimenez C, Riguera R. NMR methods for unravelling the spectra of complex mixtures. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:78–98. doi: 10.1039/c005320c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinette SL, Bruschweiler R, Schroeder FC, Edison AS. NMR in metabolomics and natural products research: two sides of the same coin. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:288–297. doi: 10.1021/ar2001606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauli GF, Godecke T, Jaki BU, Lankin DC. Quantitative 1H NMR. Development and potential of an analytical method: an update. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:834–851. doi: 10.1021/np200993k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera C, Artacho R, Gimenez R. Beneficial effects of green tea - a review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2006;25:79–99. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuo Y, Chen H, Deng Y. Simultaneous determination of catechins, caffeine, and gallic acids in green, Oolong, black and pu-erh teas using HPLC with a photodiode array detector. Talanta. 2002;57:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(02)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Q, Guo Z, Zhao J. Identification of green tea’s (Camellia sinensis (L.)) quality level according to measurement of main catechins and caffeine contents by HPLC and support vector classification pattern recognition. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008;48:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro J, Pregibon T, Chumanov K, Marcus RK. Determination of catechins and caffeine in proposed green tea standard reference materials by liquid chromatography-particle beam/electron ionization mass spectrometry (LC-PB/EIMS) Talanta. 2010;82:1687–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2010.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedner M, Duewer DL. Dynamic calibration approach for determining catechins and gallic acid in green tea using LC-ESI/MS. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:6169–6176. doi: 10.1021/ac200372d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Gall G, Colquhoun IJ, Defernez M. Metabolite profiling using 1H NMR spectroscopy for quality assessment of green tea, Camellia sinensis (L.) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:692–700. doi: 10.1021/jf034828r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara M, Ando I, Arifuku K. Multivariate analysis for 1H-NMR spectra of two hundred kinds of tea in the world. Anal. Sci. 2006;22:1307–1314. doi: 10.2116/analsci.22.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarachiwin L, Ute K, Kobayashi A, Fukusaki E. 1H NMR based metabolic profiling in the evaluation of Japanese green tea quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:9330–9336. doi: 10.1021/jf071956x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J-E, Lee B-J, Chung J-O, Hwang J-A, Lee S-J, Lee C-H, Hong Y-S. Geographical and climatic dependencies of green tea (Camellia sinensis) metabolites: a 1H NMR-based metabolomics study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:10582–10589. doi: 10.1021/jf102415m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J-E, Lee B-J, Hwang J-A, Chung K-S. Ko.J.-O, Kim E-H, Lee S-J, Hong Y-S. Metabolic dependence of green tea on plucking positions revisited: a metabolomic study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:10579–10585. doi: 10.1021/jf202304z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godecke T, Napolitano JG, Rodriguez-Brasco MF, Chen S-N, Jaki BU, Lankin DC, Pauli GF. Validation of a generic quantitative 1H NMR method for natural products analysis. Phytochem. Anal. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pca.2436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pca.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Napolitano JG, Godecke T, Rodriguez-Brasco MF, Jaki BU, Chen S-N, Lankin DC, Pauli GF. The tandem of full spin analysis and qHNMR for the quality control of botanicals exemplified with Ginkgo biloba . J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:238–248. doi: 10.1021/np200949v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laatikainen R, Tiainen M, Korhonen S-P, Niemitz M. Computerized analysis of high-resolution solution-state spectra. In: Harris RK, Wasylishen RE, editors. Encyclopedia of Magnetic Resonance (eMagRes) Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2011. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen CC, Chang YS, Ho LK. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of 5,7-dihydroxyflavonoids. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:843–845. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J-K, Zhang W-K, Hiroshi K, Yao X-S. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Camellia assamica var. kucha Chang et Wang. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2009;7:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napolitano JG, Lankin DC, Chen S-N, Pauli GF. Complete 1H NMR spectral analysis often chemical markers of Ginkgo biloba . Magn. Reson. Chem. 2012;50:569–575. doi: 10.1002/mrc.3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Napolitano JG, Lankin DC, Graf TN, Friesen JB, Chen S-N, McAlpine JB, Oberlies NH, Pauli GF. HiFSA fingerprinting applied to isomers with near-identical NMR spectra: the silybin/isosilybin case. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:2827–2839. doi: 10.1021/jo302720h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells RJ, Cheung J, Hook JM. Dimethylsulfone as a universal standard for analysis of organics by QNMR. Accredit. Qual. Assur. 2004;9:450–456. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sander LC, Bedner M, Tims MC, Yen JH, Duewer DL, Porter B, Christopher SJ, Day RD, Long SE, Molloy JL, Murphy KE, Lang BE, Lieberman R, Wood LJ, Payne MJ, Roman MC, Betz JM, NguyenPho A, Sharpless KE, Wise SA. Development and certification of green tea-containing standard reference materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012;402:473–487. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schantz MM, Sander LC, Sharpless KE, Wise SA, Yen JH, Nguyen Pho A, Betz JM. Development of botanical and fish oil standard reference materials for fatty acids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013;405:4531–4538. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6747-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schantz MM, Bedner M, Long SE, Molloy JL, Murphy KE, Porter BJ, Putzbach K, Rimmer CA, Sander LC, Sharpless KE, Thomas JB, Wise SA, Wood LJ, Yen JH, Yarita T, NguyenPho A, Sorenson WR, Betz JM. Development of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) fruit and extract standard reference materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:427–438. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimmer CA, Howerton SB, Sharpless KE, Sander LC, Long SE, Murphy KE, Porter BJ, Putzbach K, Rearick MS, Wise SA, Wood LJ, Zeisler R, Hancock DK, Yen JH, Betz JM, NguyenPho A, Yang L, Scriver C, Willie S, Sturgeon R, Schaneberg B, Nelson C, Skamarack J, Pan M, Levanseler K, Gray D, Waysek EH, Blatter A, Reich E. Characterization of a suite of ginkgo-containing standard reference materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007;389:179–196. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharpless KE, Thomas JB, Christopher SJ, Greenberg RR, Sander LC, Schantz MM, Welch MJ, Wise SA. Standard reference materials for foods and dietary supplements. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007;389:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1315-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao Y, Li W, Liang W, van Breemen RB. Identification and quantification of gingerols and related compounds in ginger dietary supplements using high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:10014–10021. doi: 10.1021/jf9020224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Chow W, Leung D. Applications of LC/ESI-MS/MS and UHPLC/Qq-TOF-MS for the determination of 141 pesticides in tea. J. AOAC Int. 2011;94:1685–1714. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.sgewang. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.