Abstract

Labelled 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) binding experiments have shown that expression levels of (yet unidentified) membrane androgen receptors (mAR) are elevated in prostate cancer and correlate with a negative prognosis. However, activation of these receptors which mediate a rapid androgen response can counteract several cancer hallmark functions such as unlimited proliferation, enhanced migration, adhesion and invasion and the inability to induce apoptosis. Here, we investigate the downstream signaling pathways of mAR and identify rapid DHT induced activation of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) in primary cultures of human prostate epithelial cells (hPEC) from non-tumorous tissue. Consequently, down-regulation of Orai1, the main molecular component of Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels results in an almost complete loss of DHT induced SOCE. We demonstrate that this DHT induced Ca2+ influx via Orai1 is important for rapid androgen triggered prostate specific antigen (PSA) release. We furthermore identified alterations of the molecular components of CRAC channels in prostate cancer. Three lines of evidence indicate that prostate cancer cells down-regulate expression of the Orai1 homolog Orai3: First, Orai3 mRNA expression levels are significantly reduced in tumorous tissue when compared to non-tumorous tissue from prostate cancer patients. Second, mRNA expression levels of Orai3 are decreased in prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and DU145 when compared to hPEC from healthy tissue. Third, the pharmacological profile of CRAC channels in prostate cancer cell lines and hPEC differ and siRNA based knock-down experiments indicate changed Orai3 levels are underlying the altered pharmacological profile. The cancer-specific composition and pharmacology of CRAC channels identifies CRAC channels as putative targets in prostate cancer therapy.

Keywords: Membrane androgen receptor, Orai channel, CRAC channel, prostate cancer, Ca2+ signaling

INTRODUCTION

In classical steroid receptor pathways, hormones cross the plasma membrane and bind to their cytosolic receptors. Subsequently, these complexes translocate to the nucleus where they trigger gene expression important for many physiological and pathophysiological functions and thus are targets for therapeutic strategies [1-3]. In contrast to the classical pathway where the hormonal effects appear after hours, many cell types display rapid hormone signaling upon steroid hormone stimulation mediated by receptors or ion channels located at the cell surface [4, 5].

Even though the molecular identity of mAR is still elusive, their presence has been demonstrated in the membrane of primary prostate tissue and was correlated to the level of differentiation of prostate carcinoma [6, 7]. mAR are existent in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cell line LNCaP [8] as well as in androgen-insensitive prostate cancer cell lines DU145 and PC3 [9, 10]. Rapid DHT signaling results in rearrangements of the cytoskeleton, PSA production, inhibition of proliferation, migration, adhesion and invasion and apoptotic regression of prostate cancer cells [8, 11, 12]. Several studies in mice demonstrated the clinical relevance of targeting mAR in prostate cancer therapy. Macroscopic tumors are reduced upon treatment with testosterone-albumin conjugates, binding exclusively to mAR. In addition, testosterone-BSA triggers tumor cell apoptosis as the fraction of apoptotic cells in tumorous tissue is elevated. Co-medication of mice with paclitaxel and testosterone-BSA results in additive tumor inhibitory rates up to ~92% [11, 12]. Taken together, targeting mAR pathways in prostate cancer is a highly promising strategy especially as no toxic effects of testosterone-albumin conjugates have been reported in these studies [13].

As a universal mechanism rapid androgen signaling includes an increase in intracellular Ca2+ as second messenger [4]. Previous work proposed that the mAR induced increase in intracellular Ca2+ arises from intracellular Ca2+ store depletion and the Ca2+ influx via voltage gated Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane in LNCaP cells [14].

During the last few years the molecular components of SOCE and the underlying Ca2+ current ICRAC (Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current) have been identified: stromal interaction molecule STIM1 [15, 16] and plasma membrane protein Orai1 [17-19]. Upon Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, Ca2+ dissociates from an EF hand motif in the luminal section of STIM1. STIM1 molecules cluster and activate Ca2+ influx via Orai1 ion channels in the plasma membrane [20-24]. A number of studies of the STIM1 homologue STIM2 and the Orai1 homologues Orai2 and Orai3 increasingly reveal disease related roles for these less prominent but ubiquitously expressed isoforms [25].

ICRAC mediates a plethora of cellular functions including cell cycle regulation, proliferation and apoptosis [26]. In prostate cancer, Ca2+ signaling via ICRAC channels is decreased and subsequently, the low ICRAC contributes to cancer hallmark functions in particular uninhibited proliferation and the inability to induce apoptosis [27-29]. In addition, low expression levels of Orai1 can protect LNCaP cells from several apoptotic pathways [30].

Here, we investigate the role of ICRAC channel components in Ca2+ signaling in the rapid response to DHT stimulation. We compare expression levels of STIM1, STIM2, Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3 in tumorous and non-tumorous tissue from prostate cancer patients. In addition, we examine the pharmacological profile of ICRAC in hPEC from non-tumorous tissue and prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP and DU145 to investigate ICRAC's molecular key players as potential therapeutic targets.

RESULTS

DHT induces SOCE in hPEC

First, we investigate the molecular key players in androgen induced Ca2+ signaling in hPEC. Application of 100 nM DHT in Ca2+ free solution induces a substantial increase in intracellular Ca2+ due to Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores as has been described earlier [14]. The subsequent addition of 2 mM Ca2+ induced a rapid increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration thus confirming that DHT induces SOCE in hPEC. Control cells on which no DHT has been applied release Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores to some extent, possibly induced by the Ca2+ free solution. But both, Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores and SOCE are almost reduced to zero in control cells (Figure 1A). Supplementary Figure 1A shows that store-depletion by sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) inhibitor thapsigargin (tg) evokes SOCE, confirming the principle mechanism of SOCE in hPEC.

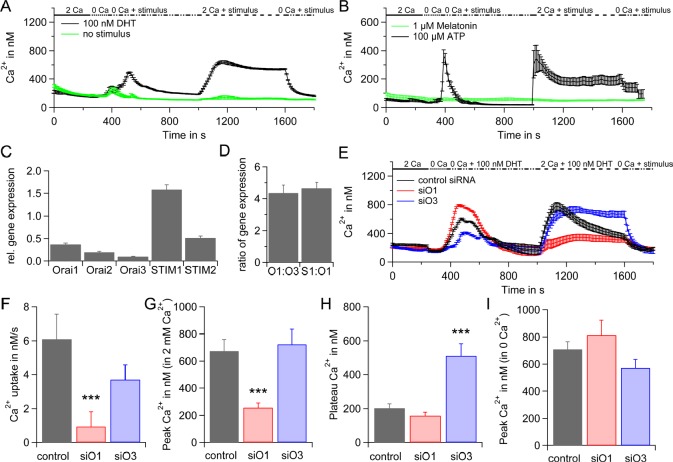

Figure 1. SOCE in hPEC.

A) Average intracellular Ca2+ responses (±SEM) from a Fura-2 based Ca2+ imaging assay when 100 nM DHT, (n = 44) or no stimulus (n = 14) were applied are blotted vs. time. Extracellular Ca2+ concentration is indicated in mM. B) Same as A but either 100 μM ATP, n = 37 (black), or 1 μM Melatonin, n = 14 (green) were used as stimulus. C) qRT-PCR analyses of Orai1, Orai2, Orai3, STIM1 and STIM2 expression levels from hPEC from 17 different patients normalized to TATA box binding protein (TBP) expression as reference gene. D) Ratio of Orai1:Orai3 and STIM1:Orai1 expression levels. E) DHT induced intracellular Ca2+ responses in cells transfected with control RNA (black, n = 38), Orai1 siRNA (red, n = 33) or Orai3 siRNA (blue, n = 36). F) Average Ca2+ influx rates for cells in E when 2 mM Ca2+ and 100 nM DHT were applied. G) Average of Ca2+ peaks for cells in E when 2 mM Ca2+ and 100 nM DHT were applied when baseline for every cell was subtracted. H) Average Ca2+ plateaus for cells in E when 2 mM Ca2+ and 100 nM DHT were applied at t = 1600 s and baseline for every cell was subtracted. I) Average Ca2+ peaks after store depletion with 100 nM DHT in Ca2+ free Ringer for cells in E when baseline for every cell was subtracted.

Adenosine-5'-triphosphate (ATP) has been described as signal molecule for prostate epithelial cells [31] as well as melatonin [32]. Application of 100 μM ATP activates SOCE but 1 μM melatonin does not (Figure 1B) suggesting that ATP induced signaling includes SOCE pathways whereas melatonin signaling pathways do not.

Please note that basal Ca2+ levels vary between 100 nM and 200 nM (Figure 1A and 1B and Supplementary Figure 1A) most likely as data were generated with cell preparations from different patients.

Based on these initial findings we analysed gene expression levels of CRAC channel components Orai1, Orai2, Orai3, STIM1 and STIM2 by qRT-PCR in hPEC from 17 different patients (Figure 1C and Supplementary 1B). Our data suggest that CRAC channels in hPEC are mainly formed by STIM1 and Orai1. Figure 1D represents the ratio of Orai1:Orai3 and STIM1:Orai1 expression pointing towards an STIM1:Orai1 ratio of 4.6±0.4, which, assuming a linear correlation between mRNA and protein levels would be above optimal for maximal SOCE activation [33] and a relatively low Orai1:Orai3 ratio of 4.3±0.5 (for comparison, the Orai1:Orai3 ratio is ~70 in naïve and ~25 in effector TH cells, [34]). The latter points towards a contribution of approximately one Orai3 subunit to the functional CRAC channel, that has been described as either tetramer [35-40] or hexamer [41] in the past.

The down-regulation of the SOCE component Orai1 by siRNA significantly reduced the Ca2+ influx rate and peak of SOCE and the Ca2+ plateau is decreased when compared to SOCE in cells transfected with non-silencing control RNA (Figure 1E, F, G and H). The down-regulation of Orai3 had little effect on the Ca2+ influx rate and peak of SOCE, but significantly increased the Ca2+ plateau (Figure 1E, F, G and H). Knock-down efficiencies are shown in Fig. S1c. In order to investigate if down-regulation of Orai1 or Orai3 leads to differences in Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores, we subtracted base lines from DHT induced Ca2+ peaks in 0 Ca2+ for single cells and analysed the averages. The differences in the degree of store depletion are not significant (Figure 1I).

In conclusion, these data show that rapid DHT response involves Ca2+ signaling via ICRAC channels and indicate a key role for Orai1 whereas the function of Orai3 is less clear.

Molecular components of ICRAC mediate rapid DHT response

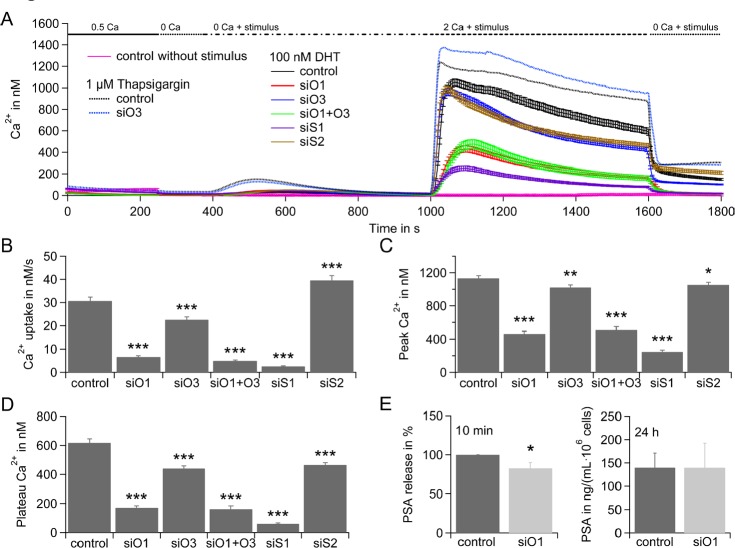

In order to investigate molecular components of DHT induced SOCE, we used the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. In a siRNA based assay in LNCaP cells that were cultured in hormone deprived media for 48 h, down-regulation of SOCE components STIM1, STIM2, Orai1, Orai3 or Orai1 and Orai3 led to an overall decrease of DHT induced SOCE when compared to control RNA treated cells (solid lines, Figure 2A). Gene expression levels and efficiency of down-regulation from cells cultured in hormone deprived media for 48 h are shown in Supplementary Figure 2A and B. Down-regulation of STIM1, Orai1, Orai3 or Orai1 and Orai3 results in a significant decrease of Ca2+ influx rate (Figure 2B), Ca2+ peak (Figure 2C) and Ca2+ plateau (Figure 2D) of SOCE. Down-regulation of STIM2 significantly increased Ca2+ influx rate (Figure 2B), possibly due to a loss of STIM2 suppressing function of STIM1 as described earlier by [42]. Interestingly, STIM2 down-regulation also significantly decreased Ca2+ peak (Figure 2C) and Ca2+ plateau (Figure 2D) of SOCE. Global store-depletion by tg results in a higher Ca2+ signal upon Ca2+ release and higher SOCE when compared to DHT induced SOCE (black dotted line (tg) versus black solid line (DHT), Figure 2A). Down-regulation of Orai3 does not decrease but significantly increase Ca2+ influx rate, Ca2+ peak and Ca2+ plateau of tg-induced SOCE (Figure 2A and supplementary Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Rapid DHT response in LNCaP depends on SOCE.

A) Average intracellular Ca2+ responses (±SEM) from a Fura-2 based Ca2+ imaging assay when stores are depleted by application of 100 nM DHT (solid lines) and cells were transfected with control RNA (control, black curve, n = 132), Orai1 siRNA (siO1, red curve, n = 117), Orai3 siRNA (siO3, blue curve, n = 126), Orai1 and Orai3 siRNA (siO1+O3, green curve, n = 77), STIM1 siRNA (siS1, purple curve, n = 137), STIM2 siRNA (siS2, brown curve, n = 180), or stores are depleted by application of 1 μM tg (dotted line) and cells were transfected with control RNA (control, black curve, n = 228) or Orai3 siRNA (siO3, blue curve, n = 227) or stores were not depleted (no stimulus) and transfected with control RNA (pink curve, n = 45). Extracellular Ca2+ concentration is indicated in mM. B) Average Ca2+ influx rates from cells in A, when 100 nM DHT and 2 mM Ca2+ were applied. C) Average Ca2+ peaks from cells in A, when 100 nM DHT and 2 mM Ca2+ were applied and baseline for every cell was subtracted. D) Average Ca2+ plateaus from cells in A, when 100 nM DHT and 2 mM Ca2+ were applied and baseline for every cell was subtracted. E) PSA concentration in the media 10 min after stimulation with 100 nM DHT (double determination in n = 5 experiments) and PSA concentration in the media 24 h after stimulation with 100 nM DHT (double determination in n = 3 experiments) when cells were transfected with control RNA or Orai1 siRNA.

We next tested for Orai1's contribution to rapid androgen induced PSA release. Rapid DHT signaling increased basal PSA production up to 20% in LNCaP cells [8]. Comparison of PSA release from LNCaP cells transfected with control RNA (0.48±0.08 ng·mL−1·106 cells−1) or with Orai1 specific siRNA (0.39±0.07 ng·mL−1·106 cells−1) demonstrates that DHT induced PSA release depends on Orai1 whereas long-term gene expression (after 24 h) dependent PSA release appears to be independent on Orai1 (Figure 2E). In summary, knock-down molecular components of ICRAC results in decreased Ca2+ signaling upon DHT stimulation. Down-regulation of main component of CRAC channel component Orai1 reduces DHT induced PSA release.

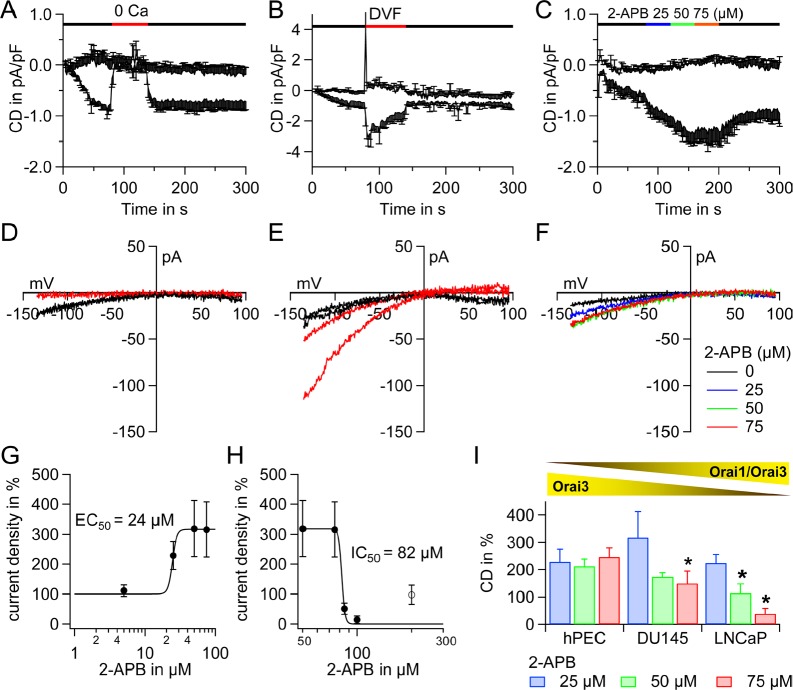

ICRAC exhibits a unique 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile in hPEC

Next, we tested for the properties of ICRAC in hPEC in patch clamp experiments in order to investigate typical electrophysiological hallmarks of ICRAC. We evoked ICRAC in a 20 mM Ca2+ Ringer solution by adding 10 mM BAPTA and 50 μM inositol-1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3) to the patch pipette. In these cells ICRAC is ~ 0.5 – 1 pA/pF (Figure 3A, 3B and 3C). Application of 0 mM Ca2+ abolishes ICRAC (Figure 3A, current-voltage curves IVs shown in Figure 3D) and upon application of divalent free solution (DVF) ICRAC exhibits large inwardly rectified Na+ currents (Figure 3B, IVs shown in Figure 3E). These characteristics are in very good agreement to the literature about native CRAC channels (as discussed below). In many native cells as well as in STIM1/Orai1 overexpression systems, application of 2-APB (50 μM) amplifies and subsequently blocks ICRAC (EC50 ~3 – 4 μM, IC50 ~ 8 – 10 μM, [43, 44]). Surprisingly, the 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile of hPEC (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure 3A, IVs shown in Figure 3F and Supplementary Figure 3D and 2-APB induced dose-responses Figure 3G and H) differs from what is described for native CRAC channels and STIM1/Orai1 overexpression systems. The EC50 for potentiation is ~24 μM (Figure 3G) and the IC50 for inhibition is 82 μM (Figure 3H). The Orai1:Orai3 ratio in prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP und DU145 is elevated compared to hPEC (Orai1:Orai3 = 17±0.9, n = 4, in DU145 and Orai1:Orai3 = 26±0.9, n = 4, in LNCaP calculated from gene expression levels shown in Supplementary Figure 4A). Identical to the experiment in hPEC (Figure 3C and 3F) we determined the 2-APB induced electrophysiological profile in prostate cancer cell lines DU145 (Supplementary Figure 3B and 3E) and LNCaP (Supplementary Figure 3C and 3F). The statistical analysis in Figure 3I reveals a significant difference in pharmacological profile in DU145 upon application of 75 μM 2-APB and a significant difference in pharmacological profile in LNCaP upon application of 50 or 75 μM 2-APB when compared to hPEC from non-tumorous tissue.

Figure 3. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of ICRAC in hPEC and prostate cancer cell lines.

A Time course of ICRAC evoked in hPEC by 50 μM IP3 and 10 mM BAPTA in the patch pipette and 20 mM Ca2+ Ringer in the bath. A 0 mM Ca2+ Ringer (0 Ca) was applied as indicated by the red bar (n = 4). B Same as in A, but a divalent free (DVF) external Ringer was applied as indicated by the red bar (n = 4). C Same as in A, but 2-APB was applied as indicated (n = 5). D corresponding IVs to A. E corresponding IVs to B. F corresponding IVs to C. G Current densities when 2-APB was applied were normalized to IP3 induced current at t = 80 s in %. 2-APB induced current potentiation was analysed with a dose-response fit function and an EC50 of 24 μM for potentiation was determined. H Same as G but 2-APB induced current inhibition was analysed. Data were fitted with a dose-response fit function and an IC50 of 82 μM for inhibition was determined. I Statistical analysis of 2-APB induced pharmacological profile of hPEC from cells in Figure 3C, DU145 (n=6) and LNCaP (n=6) from experiments performed as in Figure 3C.

As Orai3 is largely expressed in hPEC we next wanted to test if heteromeric Orai1/Orai3 channels might be responsible for the 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile.

Orai3 is a regulator of SOCE and is responsible for the 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile of ICRAC in LNCaP cells

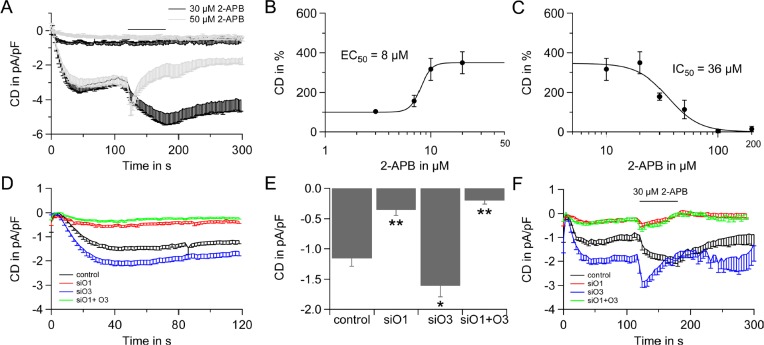

Given the extraordinary 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile of hPEC (Figure 3), the low Orai1:Orai3 ratio of ~4 (Figure 1) and Orai3's property to enhance Ca2+ currents upon 2-APB application [44-48] we tested the ability of Orai3 to shape the 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile of ICRAC in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP as LNCaP are less delicate to patch after transfection than hPEC. When 2-APB is applied in a concentration of 30 μM, ICRAC is enhanced and application of 50 μM 2-APB results in current enhancement followed by an incomplete current block (Figure 4A, IVs are shown in Supplementary Figure 4C and 4D) as has previously been shown by [49]. In these cells, ICRAC exhibits an EC50 of 8 μM (Figure 4B) and an IC50 of 36 μM (Figure 4C). Figure 4D shows ICRAC in a siRNA based assay, when Orai1, Orai3, or both proteins are down-regulated. Analysis of IP3 induced currents show, that down-regulation of Orai3 significantly increases current size, while down-regulation of Orai1 or Orai1 and Orai3 significantly decreases the current size (Figure 4D and 4E). Upon siRNA based knock-down residual gene expression on mRNA level range from 11±5 % to 32±7 % (Supplementary Figure 4B).

Figure 4. 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile of LNCaP cells and the role of Orai3.

A) Time course of ICRAC evoked in LNCaP cells by 50 μM IP3 and 10 mM BAPTA in the patch pipette and 20 mM Ca2+ Ringer in the bath. 2-APB was applied as indicated (30 μM, n = 10, black line and 50 μM, n = 10, grey line). B) Dose response for 2-APB induced potentiation, EC50 = 8 μM. C) Dose response for inhibition of ICRAC by 2-APB, IC50 =36 μM. D) Time course of ICRAC evoked as in A from LNCap cells transfected with non-silencing control RNA (control, black, n = 21), transfected with Orai1 siRNA (O1, red, n = 30), Orai3 siRNA (O3, blue, n = 37) or Orai1 and Orai3 siRNA (siO1+O3, green, n = 29). Some of the cells in D are also shown in F. E) Current density at 120 s and statistical analysis for cells from D. F) Time-course of ICRAC evoked as described in A when 30 μM 2-APB is applied on cells transfected with control RNA (control, black, n = 11), transfected with Orai1 siRNA (siO1, red, n=11), Orai3 siRNA (siO3, blue, n = 8) or Orai1 and Orai3 siRNA (siO1+O3, green, n = 9).

Whereas ICRAC in control RNA transfected cells is amplified upon application of 30 μM 2-APB, down-regulation of Orai1 or Orai1 and Orai3 results in an almost complete loss of 2-APB induced current. The fact that both knock-down conditions give the same result implies that Orai1 is the stringent requirement for a functional SOCE and that in LNCaP cells the CRAC channel likely exists as a heteromeric Orai1/Orai3 channel. Down-regulation of Orai3 introduces a 2-APB induced block of ICRAC that is characteristic for STIM1/Orai1 mediated currents (Figure 4F). Thus, high expression levels of Orai3 shape a unique pharmacological profile for SOCE and Ca2+ signaling via specific CRAC channels in prostate cancer could be manipulated by substances selective for a specific channel composition.

Relative gene expression of STIM1, STIM2, Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3 in non-tumorous and tumorous tissue from 13 patients with different Gleason score

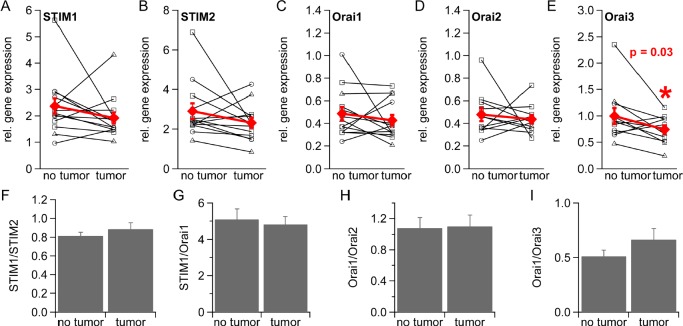

We were interested in possible changes of ICRAC component expression levels in prostate cancer as ICRAC is reduced in prostate cancer resulting in several cancer hallmark functions. We thus determined relative STIM and Orai expression levels in non-tumorous and tumorous tissue from 13 prostate cancer patients by qRT-PCR, from which 13 expressed detectable levels of STIM1, STIM2 and Orai1 and 11 detectable levels of Orai2 and Orai3 (see methods). We find an over-all down-regulation of all ICRAC components when gene expression is normalized to TBP (Figure 5A, 5B, 5C, 5D and 5E) or RNAPol (Supplementary Figure 5A, 5B, 5C, 5D and 5E). The different Gleason scores of prostate cancer tumors is indicated by symbols as described in the figure legend. For analysis we pooled data from patients with different Gleason scores. Orai3 is significantly down-regulated when gene expression levels are normalized to TBP (Figure 5E, p = 0.03 and p = 0.04 when gene expression levels are normalized to RNAPol, Supplementary Figure 5E). Levels of STIM1:STIM2, STIM1:Orai1, and Orai1:Orai3 gene expression ratios are slightly changed in tumorous tissue (Figure 5F, 5G and 5I and Supplementary Figure 5F, 5G and 5I) whereas the Orai1:Orai2 ratio remains unchanged (Figure 5H and Supplementary Figure 5H).

Figure 5. Gene expression of STIM1, STIM2, Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3 in healthy and tumorous human prostate tissue.

Relative gene expression of STIM1 (n = 13), STIM2 (n = 13), Orai1 (n = 13), Orai2 (n = 11) and Orai3 (n = 11) in healthy and tumorous tissue from prostate cancer patients normalized to the reference gene TBP and sorted by Gleason Score (○= 6, □= 7 and △= 8) (A-E) F) STIM1:STIM2 ratio. G) STIM1:Orai1 ratio. H) Orai1:Orai2 ratio. I) Orai1:Orai3 ratio.

Our data suggest a down-regulation of ICRAC components in prostate cancer and support the concept of low Ca2+ signaling in prostate cancer cells. Orai3 is significantly down-regulated and the decrease in Orai1:Orai3 ratio might reflect a different stoichiometry of Orai1/Orai3 subunits in CRAC channel that open the possibility for specific therapeutic targeting in prostate cancer.

DISCUSSION

ICRAC mediates several cellular functions such as cell cycle regulation, proliferation and apoptosis [26]. In prostate cancer, ICRAC is well-known to be off-balance [50] and ICRAC channels together with a variety of other Ca2+-transporting enzymes are under investigation as therapeutic targets [51, 52].

Our results uncover that STIM1 and Orai1 are ICRAC's major molecular components in hPEC and STIM2, Orai2 and Orai3 are also expressed. ICRAC channels are thought to exist either as tetramers [35-40] or as hexamers [41] and the low Orai1:Orai3 ratio of 4.3 supports the concept of heteromeric Orai1/Orai3 channels in hPEC.

ICRAC in hPEC exhibits high Ca2+ selectivity and large monovalent currents in the absence of divalent ions comparable to native CRAC currents from Jurkat T cells, rat basophilic leukaemia cells (RBL) and mast cells [53-55]. The 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile in hPEC is unique with high EC50 and IC50 values (EC50 = 24 μM and IC50 = 82 μM) when compared to ICRAC in a Jurkat T-cell line (EC50 = 3 μM and IC50 = 10 μM [43]) and STIM1 Orai1 overexpression systems (EC50 = 4 μM and IC50 = 8 μM [44]). Investigation of the 2-APB specific electrophysiological profile in a siRNA based assay in LNCaP cells suggest Orai1/Orai3 heteromeric channels as molecular basis for this unique pharmacology.

We find a significant down-regulation of Orai3 gene expression in tumorous tissue when compared to non-tumerous tissue from prostate cancer patients and an increased Orai1:Orai3 ratio. In addition, a comparison of Orai1:Orai3 gene expression ratios and electrophysiological profiles upon application of 2-APB in prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP, DU145 and hPEC support the idea of low levels of Orai3 in prostate cancer, although Orai3 is not reduced per se in cancer. In breast cancer tissue, Orai3 is up-regulated when compared to healthy tissue and its signaling includes cell cycle progression, apoptosis resistance, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway and tumor formation [56-59]. The altered composition of CRAC channels in prostate cancer with a shift in Orai1:Orai3 ratio and distinct pharmacological profiles open the possibility to selectively manipulate ICRAC activity in cancer cells (e.g. to higher Ca2+ signals and thereby drive cancer cells into apoptosis) without effecting Ca2+ signals in non-cancerous cells.

Targeting mAR and mAR induced signaling pathways is an intriguing strategy in the development of therapeutic approaches in prostate cancer [13]. So far, the androgen-induced increase of intracellular Ca2+ has been proposed to be mediated via Ca2+ store-depletion and L-type Ca2+ channels and to involve a pertussis sensitive G protein-coupled receptor [14, 60]. Evidence has accumulated that mAR activation leads to production of IP3 [61] and mAR induced IP3 production leads to the binding of IP3 to the IP3 receptor and the subsequent release of Ca2+ from intracellular Ca2+ stores [62, 63]. In 1992, Hoth and Penner demonstrated that Ca2+ store depletion by IP3 triggers ICRAC [64]. Here, we demonstrate that rapid DHT signaling induces Ca2+ influx via CRAC channels in hPEC and a knock-down of the pore forming ICRAC channel subunit Orai1 results in a dramatic reduction of mAR induced Ca2+ transients in hPEC. In addition, Ca2+ signaling via Orai1 functionally supports PSA release in rapid DHT response.

mAR exhibit higher expression levels in human prostate carcinoma cells when compared to non-tumorous and hyperplastic cells related to the Gleason score of the tumor [6, 7]. Higher expression levels of mAR are likely to increase store-depletion that is below maximum at DHT concentrations of 100 nM in LNCaP cells (compare store-depletion in Figure 2A, DHT vs tg) due to an elevated IP3 production. Patch clamp and imaging experiments indicate down-regulation of Orai3 results in elevated SOCE and ICRAC when Ca2+ stores are heavily depleted by either tg or IP3 (Figure 2A, 4D and 4E and Supplementary Figure 2C).

We suggest that high mAR expression levels lead to stronger store depletion and in combination with Orai3 down-regulation to higher Ca2+ signals in prostate cancer. Once induced these elevated Ca2+ signals could bear the potential to counteract cancer hallmark functions that are characterized by low Ca2+ signaling e.g. uninhibited proliferation and inability to induce apoptosis. Thus, selective enhancement of ICRAC channels in prostate cancer cells can be a promising approach in the development of mAR therapy.

At the moment a novel therapeutic approach against prostate cancer is tested in a clinical trial [65], tg coupled to a chemical cage that is specially cleaved of by prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) a prostate specific protease [66]. This so-called smart bomb is active only in prostate cancer cells. ICRAC channels might be pharmacologic targets for the treatment of prostate cancer if they can be selectively manipulated without affecting ICRAC channels in healthy cells. Thus, future therapies could include smart bombs on prostate cancer-specific ICRAC channels.

MATERIAL & METHODS

Cell culture and prostate tissue collection

Prostate cancer lines Lymph Node Carcinoma of the Prostate (LNCaP) and DU145 were purchased from American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured with RPMI Medium 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10 % FCS and 1 % Pen/Strep (Life Technologies).

Prostate tissue was obtained from prostectomy specimens (Ethics approval 168/05, Ärztekammer des Saarlandes).

Human prostate epithelial cells (hPEC) were isolated with slight modifications according to [67]. Pieces from healthy tissues are washed in phosphate buffer solution and cut into cubes with a side length of 1 mm and placed into cell culture flasks. These small tissue cubes are wetted with PrEBM (Prostate Cell Basal Medium, #CC-3165, Lonza) supplemented with PrEGM Single Quots Supplements (#CC-4177, Lonza). Under these conditions prostate epithelial cells start to form a layer around the tissue piece after 2 to 6 days. After an adequate cell layer has been formed, pieces are removed and cells are taken in culture. For passaging Cell Dissociation Solution (#C5789, Sigma) was used to detach cells and cells were not grown in media described above.

For comparison of expression levels of target genes via qRT-PCR in healthy and cancer prostate tissues primary prostate adenocarcinoma samples, which were obtained after radical prostatectomy from thus far untreated prostate cancer patients, were investigated. Following prostatectomy, the specimens were dissected by a pathologist, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C. Only samples containing >50% tumor cells were included in the study. In the present subset of 13 prostate cancer samples were classified with Gleason score as indicated.

Quantitative RealTime-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from LNCaP, DU145 and hPEC was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies) and from prostate cancer tissue with RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). For reverse transcription 0.8 μg of isolated total RNA was used.

0.5 μl complementary DNA (cDNA) and 300 nM primer were used in a QuantiTect SYBRgreen kit (Qiagen). PCR conditions were as follows: 15 min at 95°C; 45 cycles, 30 s at 95°C; 45 s at 58°C; and 30 s at 72°C and finally a cycle (60 s, 95°C; 30 s 55°C; 30 s 95°C) to determine specificity by a dissociation curve using the MX3000 cycler (Stratagene). Expression of target genes were normalized to the expression of the reference genes RNA polymerase II (RNAPol, NM_000937) and/or TATA box binding protein (TBP, NM_003194). Primer sequences were as follows for Orai1 5'atgagcctcaacgagcact3' (forward) and 5'gtgggtagtcgtggtcag3' (reverse), for Orai3 were 5'gtaccgggagttcgtgca3' (forward) and 5'ggtactcgtggtcactct3' (reverse), for STIM1 were 5' cagagtctgcatgaccttca 3' (forward) and 5' gcttcctgcttagcaaggtt 3' (reverse), for STIM2 were 5' gtctccattccaccctatcc 3' (forward) and 5' ggctaatgatccaggaggtt 3' (reverse), TBP were 5' cggagagttctgggattgt 3' (forward) and 5' ggttcgtggctctcttatc 3' (reverse) and RNAPol were 5' ggagattgagtccaagttca 3' (forward) and 5' gcagacacaccagcatagt 3' (reverse).

Ca2+ Imaging

Bath solution contained (in mM): 155 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 5 HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH), and CaCl2 was adjusted as indicated. Stock solutions of tg were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 1 mM and of DHT in ethanol at a concentration of 5 mM. For Ca2+ imaging assays (see below) LNCaP cells and hPEC were cultured for 48 h in hormone deprived RPMI media (Sigma R7509), supplemented with 10% charcoal stripped FBS (Sigma F6765) and 2 mM L-glutamine, when DHT was used as a stimulus.

Cells were plated on glass cover slips for at least 24 h and loaded with 1 μM Fura-2/AM at 37°C for 20 min. Afterwards glass coverslips were placed in a perfusion chamber in a Zeiss Axio Observer.A1 fluorescence microscope equipped with a “Plan-Neofluar” 20x/0.4 objective (Zeiss). The excitation light generated by a Polychrome V in a TILL Photonics realtime imaging system alternated at 340 and 380 nm and the exposure time was set to 50 ms in each channel. Light intensity at emission wavelength 440 nm was detected every 5 s and digitized by a charge-coupled device camera (Q-Imaging Retiga 2000RV). Data was analysed with TILL Vision software. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration was calculated from the equation [Ca2+]i = K(R − Rmin)/(Rmax – R) in which K, R, Rmin and Rmax where determined in the corresponding in situ calibration for hPEC and LNCaP cells according to [68].

Electrophysiology

Tight seal whole-cell patch clamp experiments were performed with a Patchmaster software controlled EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA). The fire-polished patch-pipettes had resistances between 2 and 4 ΩM. Voltage ramps of 50 ms duration were delivered every 2 s from a holding potential of 0 mV spanning −150 mV to +100 mV for hPEC and −150 mV to +150 mV for the LNCaP cells. Capacitive currents were determined and corrected before each voltage ramp. Current sample rate was 3 kHz and data were filtered at 1 kHz. All voltages were corrected for a liquid junction potential of −10 mV. For analysis leak currents before current activation were subtracted and currents extracted at −130 mV and 80 mV and blotted vs time.

The bath solutions contained in mM: 95 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 20 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 TEACl, 10 CsCl, 10 glucose for LNCaP cells and 120 NaCl, 10 TEACl, 20 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose for hPEC. The pH was adjusted with NaOH to 7.2 and osmolarity was 300 mosmol/L for cell lines and 330 for primary prostate epithelial cells. In 0 mM Ca2+ solution CaCl2 was omitted and in divalent free solution (DVF) MgCl2 and CaCl2 were replaced by 10 mM EDTA, osmolarity was adjusted to 330 mosmol/L with glucose. In 2-APB experiments 2-APB was added as indicated. Pipette solution contained in mM: 120 Cs glutamate, 10 BAPTA, 10 HEPES, 3 MgCl2 and 0.05 IP3 for LNCaP cells and 140 Cs glutamate, 8 NaCl, 10 BAPTA, 10 HEPES, 3 MgCl2 and 0.05 IP3 for hPEC. For reasons of comparability DU145 and LNCaP in Fig. 3 and S3 were patched under the same conditions as hPEC.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were analyzed with TILLVision (TILL Photonics), Fitmaster 2.35 (HEKA), Igor Pro (Wavemetrics), and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft). Data are given as means ± SEM. Asterisks indicate significance determined by an unpaired, two-sided Student's t-test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Significance of changes in PSA release assays was tested with a one-sided unpaired t-test. Significance of changes of relative gene expression in tissue probes from patients was analyzed with a paired t-test. EC50 and IC50 values were determined by a fit with Hill's equations (least-squares method). For qRT-PCR relative expression was calculated according to the ΔCq method (2−ΔCq) where Cq values are determined with the MX3000 software and excluded from analysis when they exceeded 35 cycles.

Small interfering RNA transfection (siRNA)

SiRNA tranfections were perfomed with 0.12 nmol of siRNA with a Nucleofector II (Lonza) nucleofector using Nucleofector transfection Kit R (Lonza) according to manufacturer' instructions. All siRNAs were from Qiagen or Microsynth and were in part modified according to [69]. Orai1 siRNAs were Hs_TMEM142A_1, #SI03196207 [sense: 5'OMeC-OMeG-GCCUGAUCUUUAU-CG-d-(UCU)-OMeU-OMeT-OMeT3'; antisense: 3'OMeG-OMeC-CGGACUAGAAA-UA-GCAGAd(A)5'] and Hs_TMEM142A_2, #SI04215316 [sense: 5'OMeC-OMeA-ACAUCGAGGCG-GUG-A)d(GCA)OMeA-OMeT-OMeT3'; antisense: 3'OMeG-OMeT-UGUAGCUCCGCCA-CUCGUd(U)5']. Orai3 siRNAs were Hs_TMEM142C_2, # SI04174191 [sense: 5′OMeC-OMe-A-CCAGUGGCUACCUCCd(CUU)OMeA-OMeTOMeT3′; antisense: 3′OMeG-OMeT--GG-UCACCGAUGGAGGGAAd(U)5′] and Hs_TMEM142C_5, #SI04348876 [sense: 5′OMeT-OMeC-CUU-AGCCCUUGAAAU)d(ACA)OMeA-OMeT-OMeT3′; antisense: 3′OMeA--OMeG-GA-A-U-CGGGAACUUUAUGUd(U)5′]. STIM1 siRNAs were Hs_STIM1_5, # SI03235442 [sense: 5'OMeU-OMeGAGG-UGGAGGUGCAAUd(AUU)dOMeA-dOMeT-dOMeT3′; antisense: 3'OMeA-OMeC-U-C-CACCUCCACGUUAUAAd(U)5'] and Hs_STIM1_6, # SI04165175 [sense: 5'OMeC-OMeU-GGUGG-UGUCU-A-UCGUd(UAU) OMeU-OMeT-OMeT3'; antisense: 3'OMeG-OMeA-CCACCA-CA-G-AUAGCAAUAd(A)5'].

STIM2 siRNAs were Stim2_6 (Microsynth), [sense: 5'UAAGCAGCAUCCCACAU-GAdT-d-T-3'; antisense: 3'dTdTAUUCGUCGUAGGGUGUACU5'] and Stim2_7 (Microsynth), [sense-: 5'AAUUUAGAG-CGCAAAAU-GAdTdT3'; antisense: 3'dTdTUUAA-AUCU-CGCGUUUUACU5'] and Stim2_8 (Microsynth) [sense: 5'GUGCACGAACCUUCAU-U-U-A-d-Td-T3'; antisense: 3'dTdTCACGUGCUUGGAAGUAAAU5']. Non-silencing RNA were MS_control_mod [sense: 5'OmeA-OMeA-AGGUAGUGUAAUCGCd(CUU)OMeG-OmeT-OMeT3'; antisense: 3'OmeT-OmeT-UCCAUCACAUUAGCGGAAdC 5'].

Determination of prostate specific antigen (PSA)

LNCaP cells were transfected with either control or Orai1 specific siRNA and seeded in 6-well plates. After 24 h medium was replaced by hormone deprived medium for 48 h. After 100 nM DHT has been added, 250 μl of supernatant was removed at the time points indicated and total PSA within the supernatant was determined in an ECLIA (ElectroChemiLuminescence ImmunoAssay) using a cobas system (Roche). PSA was determined in ng/mL and normalized to 106 cells.

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding of several DFG projects (SFB 1027 (C4) and BO 3643/2-1 to IB, SFB 894 (A2) and PE1478/5-1 to CP). IB acknowledges funding by the AvH Foundation via the joint German-Macedonian project (DEU/1128670) and the HOMFORexcellent program of the Saarland University. VJ acknowledges funding by the Stiftung Europrofession and VJ and ES by HOMFOR of the Saarland University. We thank Helga Angeli, Petra Frieß, Gertrud Schwär and Cora Stephan for their technical support. We thank Markus Hoth for constant support and Barbara A. Niemeyer and Markus Hoth for scientific discussion and careful reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans RM. The steroid and thyroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1988;4854:889–895. doi: 10.1126/science.3283939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang P, Chandra V, Rastinejad F. Structural overview of the nuclear receptor superfamily: insights into physiology and therapeutics. Annu.Rev.Physiol. 2010:247–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleve A, Fritzemeier KH, Haendler B, Heinrich N, Moller C, Schwede W, Wintermantel T. Pharmacology and clinical use of sex steroid hormone receptor modulators. Handb.Exp.Pharmacol. 2012;214:543–587. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-30726-3_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michels G, Hoppe UC. Rapid actions of androgens. Front.Neuroendocrinol. 2008;2:182–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner TF, Loch S, Lambert S, Straub I, Mannebach S, Mathar I, Dufer M, Lis A, Flockerzi V, Philipp SE, Oberwinkler J. Transient receptor potential M3 channels are ionotropic steroid receptors in pancreatic beta cells. Nat.Cell Biol. 2008;12:1421–1430. doi: 10.1038/ncb1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dambaki C, Kogia C, Kampa M, Darivianaki K, Nomikos M, Anezinis P, Theodoropoulos PA, Castanas E, Stathopoulos EN. Membrane testosterone binding sites in prostate carcinoma as a potential new marker and therapeutic target: study in paraffin tissue sections. BMC Cancer. 2005:148. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stathopoulos EN, Dambaki C, Kampa M, Theodoropoulos PA, Anezinis P, Delakas D, Delides GS, Castanas E. Membrane androgen binding sites are preferentially expressed in human prostate carcinoma cells. BMC Clin.Pathol. 2003:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampa M, Papakonstanti EA, Hatzoglou A, Stathopoulos EN, Stournaras C, Castanas E. The human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP bears functional membrane testosterone receptors that increase PSA secretion and modify actin cytoskeleton. FASEB J. 2002;11:1429–1431. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0131fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papadopoulou N, Charalampopoulos I, Anagnostopoulou V, Konstantinidis G, Foller M, Gravanis A, Alevizopoulos K, Lang F, Stournaras C. Membrane androgen receptor activation triggers down-regulation of PI-3K/Akt/NF-kappaB activity and induces apoptotic responses via Bad, FasL and caspase-3 in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Mol.Cancer. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-88. 88-4598-7-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyng FM, Jones GR, Rommerts FF. Rapid androgen actions on calcium signaling in rat sertoli cells and two human prostatic cell lines: similar biphasic responses between 1 picomolar and 100 nanomolar concentrations. Biol.Reprod. 2000;3:736–747. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampa M, Kogia C, Theodoropoulos PA, Anezinis P, Charalampopoulos I, Papakonstanti EA, Stathopoulos EN, Hatzoglou A, Stournaras C, Gravanis A, Castanas E. Activation of membrane androgen receptors potentiates the antiproliferative effects of paclitaxel on human prostate cancer cells. Mol.Cancer.Ther. 2006;5:1342–1351. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatzoglou A, Kampa M, Kogia C, Charalampopoulos I, Theodoropoulos PA, Anezinis P, Dambaki C, Papakonstanti EA, Stathopoulos EN, Stournaras C, Gravanis A, Castanas E. Membrane androgen receptor activation induces apoptotic regression of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J.Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2005;2:893–903. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang F, Alevizopoulos K, Stournaras C. Targeting membrane androgen receptors in tumors. Expert Opin.Ther.Targets. 2013;8:951–963. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.806491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinsapir J, Socci R, Reinach P. Effects of androgen on intracellular calcium of LNCaP cells. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 1991;1:90–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91338-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J.Cell Biol. 2005;3:435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr.Biol. 2005;13:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;5777:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca(2+) influx identifies genes that regulate Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel activity. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;24:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;7090:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis RS. Store-operated calcium channels: new perspectives on mechanism and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect.Biol. 2011;12 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003970. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS. Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J.Cell Biol. 2006;6:803–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stathopulos PB, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ames JB, Ikura M. Stored Ca2+ depletion-induced oligomerization of stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) via the EF-SAM region: An initiation mechanism for capacitive Ca2+ entry. J.Biol.Chem. 2006;47:35855–35862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu P, Lu J, Li Z, Yu X, Chen L, Xu T. Aggregation of STIM1 underneath the plasma membrane induces clustering of Orai1. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 2006;4:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smyth JT, DeHaven WI, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Role of the microtubule cytoskeleton in the function of the store-operated Ca2+ channel activator STIM1. J.Cell.Sci. 2007;Pt 21:3762–3771. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoth M, Niemeyer BA. The Neglected CRAC Proteins: Orai2, Orai3, and STIM2. Curr.Top.Membr. 2013:237–271. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407870-3.00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Putney JW. The physiological function of store-operated calcium entry. Neurochem.Res. 2011;7:1157–1165. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0383-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanden Abeele F, Skryma R, Shuba Y, Van Coppenolle F, Slomianny C, Roudbaraki M, Mauroy B, Wuytack F, Prevarskaya N. Bcl-2-dependent modulation of Ca(2+) homeostasis and store-operated channels in prostate cancer cells. Cancer.Cell. 2002;2:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapovalov G, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Calcium Channels and Prostate Cancer. Recent.Pat.Anticancer Drug Discov. 2012 doi: 10.2174/15748928130103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Ion channels and the hallmarks of cancer. Trends Mol.Med. 2010;3:107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flourakis M, Lehen'kyi V, Beck B, Raphael M, Vandenberghe M, Abeele FV, Roudbaraki M, Lepage G, Mauroy B, Romanin C, Shuba Y, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Orai1 contributes to the establishment of an apoptosis-resistant phenotype in prostate cancer cells. Cell.Death Dis. 2010:e75. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasilenko WJ, Cooper J, Palad AJ, Somers KD, Blackmore PF, Rhim JS, Wright GL, Jr, Schellhammer PF. Calcium signaling in prostate cancer cells: evidence for multiple receptors and enhanced sensitivity to bombesin/GRP. Prostate. 1997;3:167–173. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970215)30:3<167::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiu SY, Pang B, Tam CW, Yao KM. Signal transduction of receptor-mediated antiproliferative action of melatonin on human prostate epithelial cells involves dual activation of Galpha(s) and Galpha(q) proteins. J.Pineal Res. 2010;3:301–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilch T, Alansary D, Peglow M, Dorr K, Rychkov G, Rieger H, Peinelt C, Niemeyer BA. Mutations of the Ca2+-sensing Stromal Interaction Molecule STIM1 Regulate Ca2+ Influx by Altered Oligomerization of STIM1 and by Destabilization of the Ca2+ Channel Orai1. J.Biol.Chem. 2013;3:1653–1664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogeski I, Kummerow C, Al-Ansary D, Schwarz EC, Koehler R, Kozai D, Takahashi N, Peinelt C, Griesemer D, Bozem M, Mori Y, Hoth M, Niemeyer BA. Differential redox regulation of ORAI ion channels: a mechanism to tune cellular calcium signaling. Sci.Signal. 2010;115:ra24. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ji W, Xu P, Li Z, Lu J, Liu L, Zhan Y, Chen Y, Hille B, Xu T, Chen L. Functional stoichiometry of the unitary calcium-release-activated calcium channel. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2008;36:13668–13673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806499105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penna A, Demuro A, Yeromin AV, Zhang SL, Safrina O, Parker I, Cahalan MD. The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature. 2008;7218:116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demuro A, Penna A, Safrina O, Yeromin AV, Amcheslavsky A, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Subunit stoichiometry of human Orai1 and Orai3 channels in closed and open states. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2011;43:17832–17837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114814108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madl J, Weghuber J, Fritsch R, Derler I, Fahrner M, Frischauf I, Lackner B, Romanin C, Schutz GJ. Resting state Orai1 diffuses as homotetramer in the plasma membrane of live mammalian cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2010;52:41135–41142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maruyama Y, Ogura T, Mio K, Kato K, Kaneko T, Kiyonaka S, Mori Y, Sato C. Tetrameric Orai1 is a teardrop-shaped molecule with a long, tapered cytoplasmic domain. J.Biol.Chem. 2009;20:13676–13685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900812200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ. How Many Orai's Does It Take to Make a CRAC Channel? Sci.Rep. 2013:1961. doi: 10.1038/srep01961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou X, Pedi L, Diver MM, Long SB. Crystal structure of the calcium release-activated calcium channel Orai. Science. 2012;6112:1308–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1228757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soboloff J, Spassova MA, Hewavitharana T, He LP, Xu W, Johnstone LS, Dziadek MA, Gill DL. STIM2 is an inhibitor of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ Entry. Curr.Biol. 2006;14:1465–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prakriya M, Lewis RS. Potentiation and inhibition of Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channels by 2-aminoethyldiphenyl borate (2-APB) occurs independently of IP(3) receptors. J.Physiol. 2001;(Pt 1):3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peinelt C, Lis A, Beck A, Fleig A, Penner R. 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate directly facilitates and indirectly inhibits STIM1-dependent gating of CRAC channels. J.Physiol. 2008;13:3061–3073. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.151365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lis A, Peinelt C, Beck A, Parvez S, Monteilh-Zoller M, Fleig A, Penner R. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr.Biol. 2007;9:794–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang SL, Kozak JA, Jiang W, Yeromin AV, Chen J, Yu Y, Penna A, Shen W, Chi V, Cahalan MD. Store-dependent and -independent modes regulating Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity of human Orai1 and Orai3. J.Biol.Chem. 2008;25:17662–17671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Putney JW., Jr Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J.Biol.Chem. 2007;24:17548–17556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schindl R, Frischauf I, Bergsmann J, Muik M, Derler I, Lackner B, Groschner K, Romanin C. Plasticity in Ca2+ selectivity of Orai1/Orai3 heteromeric channel. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2009;46:19623–19628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907714106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vanden Abeele F, Shuba Y, Roudbaraki M, Lemonnier L, Vanoverberghe K, Mariot P, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Store-operated Ca2+ channels in prostate cancer epithelial cells: function, regulation, and role in carcinogenesis. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:357–73. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: new roles for known actors. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2011;8:609–618. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Targeting Ca(2)(+) transport in cancer: close reality or long perspective? Expert Opin.Ther.Targets. 2013;3:225–241. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.741594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monteith GR, McAndrew D, Faddy HM, Roberts-Thomson SJ. Calcium and cancer: targeting Ca2+ transport. Nat.Rev.Cancer. 2007;7:519–530. doi: 10.1038/nrc2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoth M, Penner R. Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J.Physiol. 1993:359–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerschbaum HH, Cahalan MD. Monovalent permeability, rectification, and ionic block of store-operated calcium channels in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J.Gen.Physiol. 1998;4:521–537. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bakowski D, Parekh AB. Monovalent cation permeability and Ca(2+) block of the store-operated Ca(2+) current I(CRAC) in rat basophilic leukemia cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;5-6:892–902. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faouzi M, Hague F, Potier M, Ahidouch A, Sevestre H, Ouadid-Ahidouch H. Down-regulation of Orai3 arrests cell-cycle progression and induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells but not in normal breast epithelial cells. J.Cell.Physiol. 2011;2:542–551. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faouzi M, Kischel P, Hague F, Ahidouch A, Benzerdjeb N, Sevestre H, Penner R, Ouadid-Ahidouch H. ORAI3 silencing alters cell proliferation and cell cycle progression via c-myc pathway in breast cancer cells. Biochim.Biophys.Acta. 2013;3:752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Motiani RK, Zhang X, Harmon KE, Keller RS, Matrougui K, Bennett JA, Trebak M. Orai3 is an estrogen receptor alpha-regulated Ca2+ channel that promotes tumorigenesis. FASEB J. 2013;1:63–75. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motiani RK, Abdullaev IF, Trebak M. A novel native store-operated calcium channel encoded by Orai3: selective requirement of Orai3 versus Orai1 in estrogen receptor-positive versus estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells. J.Biol.Chem. 2010;25:19173–19183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun YH, Gao X, Tang YJ, Xu CL, Wang LH. Androgens induce increases in intracellular calcium via a G protein-coupled receptor in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. J.Androl. 2006;5:671–678. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lieberherr M, Grosse B. Androgens increase intracellular calcium concentration and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol formation via a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein. J.Biol.Chem. 1994;10:7217–7223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ElBaradie K, Wang Y, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z. Rapid membrane responses to dihydrotestosterone are sex dependent in growth plate chondrocytes. J.Steroid Biochem.Mol.Biol. 2012;1-2:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wunderlich F, Benten WP, Lieberherr M, Guo Z, Stamm O, Wrehlke C, Sekeris CE, Mossmann H. Testosterone signaling in T cells and macrophages. Steroids. 2002;6:535–538. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(01)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;6358:353–356. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clinical Trials database search results. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01056029?term=G-202&rank=2 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01056029?term=G-202&rank=2

- 66.Denmeade SR, Mhaka AM, Rosen DM, Brennen WN, Dalrymple S, Dach I, Olesen C, Gurel B, Demarzo AM, Wilding G, Carducci MA, Dionne CA, Moller JV, Nissen P, Christensen SB, Isaacs JT. Engineering a prostate-specific membrane antigen-activated tumor endothelial cell prodrug for cancer therapy. Sci.Transl.Med. 2012;140:140–86. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gmyrek GA, Walburg M, Webb CP, Yu HM, You X, Vaughan ED, Vande Woude GF, Knudsen BS. Normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells differ in their response to hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Am.J.Pathol. 2001;2:579–590. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61729-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J.Biol.Chem. 1985;6:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mantei A, Rutz S, Janke M, Kirchhoff D, Jung U, Patzel V, Vogel U, Rudel T, Andreou I, Weber M, Scheffold A. siRNA stabilization prolongs gene knockdown in primary T lymphocytes. Eur.J.Immunol. 2008;9:2616–2625. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.