Genome-wide association analysis and spatial patterning of single-nucleotide polymorphism data guide reverse genetics to identify new genes linking stress-induced proline accumulation with cellular redox and energy status.

Abstract

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) exhibits natural genetic variation in drought response, including varying levels of proline (Pro) accumulation under low water potential. As Pro accumulation is potentially important for stress tolerance and cellular redox control, we conducted a genome-wide association (GWAS) study of low water potential-induced Pro accumulation using a panel of natural accessions and publicly available single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data sets. Candidate genomic regions were prioritized for subsequent study using metrics considering both the strength and spatial clustering of the association signal. These analyses found many candidate regions likely containing gene(s) influencing Pro accumulation. Reverse genetic analysis of several candidates identified new Pro effector genes, including thioredoxins and several genes encoding Universal Stress Protein A domain proteins. These new Pro effector genes further link Pro accumulation to cellular redox and energy status. Additional new Pro effector genes found include the mitochondrial protease LON1, ribosomal protein RPL24A, protein phosphatase 2A subunit A3, a MADS box protein, and a nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase. Several of these new Pro effector genes were from regions with multiple SNPs, each having moderate association with Pro accumulation. This pattern supports the use of summary approaches that incorporate clusters of SNP associations in addition to consideration of individual SNP probability values. Further GWAS-guided reverse genetics promises to find additional effectors of Pro accumulation. The combination of GWAS and reverse genetics to efficiently identify new effector genes may be especially applicable for traits difficult to analyze by other genetic screening methods.

Identifying the genes responsible for intraspecific variation in drought response has been challenging because of the polygenic nature and environmental sensitivity of abiotic stress-responsive traits. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) is naturally distributed across a wide range of climates, and Arabidopsis accessions exhibit dramatic variation in stress response, making them a resource for understanding stress adaptation (Koornneef et al., 2004; Bouchabke et al., 2008; Verslues and Juenger, 2011; Assmann, 2013). Much of this variation is likely due to adaptation to local environmental conditions (Fournier-Level et al., 2011; Hancock et al., 2011; Lasky et al., 2012).

Mesophytic plants such as Arabidopsis typically face drought stress intermittently during the growing season or a terminal drought period near the end of the life cycle. These plants adapt to water limitation in large part through drought-induced developmental and metabolic plasticity. Such plasticity ensures that stress resistance mechanisms, which may reduce plant growth in the absence of stress, are activated only at the appropriate times. Mechanisms for sensing water limitation, downstream signaling, and functional genes directly involved in metabolism may all be involved in environment-dependent plasticity (Des Marais and Juenger, 2010; Juenger, 2013). The relatively few studies that have used accessions other than the reference accession Columbia (Col) have shown the great range of drought response that exists within Arabidopsis. For example, a panel of 17 diverse accessions exhibited dramatic differences in drought-induced gene expression patterns (Des Marais et al., 2012). Natural variation in stress response may also include differences in protein sequence, protein abundance, and posttranslational protein modification, which are less understood and more difficult to measure than gene expression.

Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping and genome-wide association (GWAS) studies offer complementary approaches to understanding natural variation. Combining metabolomics with QTL mapping has revealed extensive genetic variation in metabolism among accessions (Keurentjes et al., 2006; Lisec et al., 2008, 2009). However, most QTL studies identify intervals encompassing hundreds to thousands of genes. QTL studies typically use two or at most several parental accessions (Rakshit et al., 2012) and, therefore, evaluate only a small fraction of the natural variation in a species. In contrast, GWAS generally combines phenotype and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from 100 or more accessions to identify loci with allele frequency correlations to phenotypic variation (Atwell et al., 2010; Fournier-Level et al., 2011) or environment (Lasky et al., 2012). GWAS can thus incorporate a relatively large portion of natural variation in a species and localize associations to much smaller genomic regions, because the sampled diversity incorporates many more recombination events than traditional recombinant inbred line populations (Nordborg and Weigel, 2008). Potential disadvantages of GWAS are false-positive associations that arise from multiple testing of thousands of SNPs, false-positive associations resulting from population structure, and, conversely, the potential to miss signal (false negatives) because of low power to detect small genetic effects and limitations due to allelic heterogeneity and nonadditive effects among loci (Nordborg and Weigel, 2008; Bergelson and Roux, 2010).

Both QTL mapping and GWAS are based on correlations (in the form of linkage disequilibrium) and thus cannot by themselves prove causality. As GWAS is a relatively new approach, there are few studies that have conducted follow-up tests of candidate genes. The most extensive use of GWAS in Arabidopsis has been testing of well-studied traits such as flowering time variation, where strong phenotype-SNP associations have been found for candidate genes identified a priori from molecular genetic studies (Atwell et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010). There is relatively little precedent for using GWAS in Arabidopsis to find new genes influencing a phenotype.

GWAS generates lists of P values associated with hundreds of thousands of SNPs, each in varying degrees of linkage disequilibrium with the study phenotype and each other. Importantly, the association signal around true causal polymorphisms could vary in strength and genomic pattern for a large number of reasons, including the effect size of the polymorphism, the age of the mutation, the local pattern of recombination, as well as confounding patterns of linkage disequilibrium due to a variety of demographic and evolutionary processes. A number of heuristics can be used to sort or prioritize these SNP lists. Improving and validating practical methods for ranking candidate genes from genome scans is increasingly important as GWAS becomes more accessible (Seren et al., 2012) and applied to more phenotypes.

Low water potential-induced Pro accumulation is an example of drought-associated metabolic plasticity that has been widely observed in plants. In Arabidopsis, reductions in water potential that mimic the effects of soil drying during drought elicit up to a 100-fold increase of Pro content in the Col reference accession (Sharma and Verslues, 2010). Because it accumulates to such high levels, Pro accumulation can be important for osmotic adjustment to maintain tissue hydration and cell turgor (Voetberg and Sharp, 1991). Drought-induced Pro accumulation occurs in many plant species, and this led to the idea that higher levels of Pro would be associated with increased drought tolerance. Considerable efforts were made to use high Pro accumulation as a criterion to select genotypes with increased drought tolerance. Unfortunately, these efforts have met with limited success (Stewart and Hanson, 1980). Once the main Pro metabolism genes were cloned, several groups constructed transgenic plants with increased Pro accumulation; however, these efforts have also collectively led to ambiguous results on whether increasing Pro accumulation can by itself increase drought tolerance (for review, see Verslues and Sharma, 2010).

Recent research has given a more nuanced view of Pro metabolism and its relationship to drought tolerance (Székely et al., 2008; Szabados and Savouré, 2010; Verslues and Sharma, 2010; Sharma et al., 2011). In Arabidopsis, Pro does contribute to drought resistance, as knockout of the stress-induced Pro synthesis enzyme Δ1-PYRROLINE-5-CARBOXYLATE SYNTHETASE1 (P5CS1) severely impaired Pro accumulation and made plants hypersensitive to low water potential (Sharma et al., 2011). Loss of P5CS1 also caused increased reactive oxygen species accumulation (Székely et al., 2008). However, knockout of the Pro catabolism enzyme PROLINE DEHYDROGENASE1 (PDH1) led to even higher levels of Pro accumulation than the wild type, but the pdh1 mutants had the same low water potential-sensitive phenotype as p5cs1 mutants (Sharma et al., 2011). Also, both p5cs1 and pdh1 mutants had a similar shift to a higher NADPH-NADPH ratio, indicative of altered redox status. Thus, Pro metabolism and turnover, rather than just Pro accumulation, are important for drought resistance and have a role in buffering cellular redox status. We have also seen that Arabidopsis accessions that have low levels of Pro may have other metabolic adaptations to compensate. An example of this is the Shahdara accession, which has low Pro accumulation but instead accumulates higher levels of Leu, Ile, and other amino acids and differs in the expression of many metabolism- and redox-associated genes at low water potential (Sharma et al., 2013). More broadly, correlation of Pro accumulation with climate factors from the sites of origin of Arabidopsis accessions indicated that accessions found in dry climates tended to have lower Pro accumulation (Kesari et al., 2012). The implication is that accessions adapted to drier climates have other ways to buffer cellular metabolism and redox status such that they do not need to accumulate high levels of Pro. Such new data indicate that the traditional “more is better” model is not sufficient to describe the role of Pro in drought acclimation.

This new view of Pro shows the importance of understanding how Pro metabolism is connected to redox status, metabolic regulation, and other cellular processes. However, our knowledge of how Pro metabolism is regulated is largely confined to expression patterns of the major genes encoding Pro metabolism enzymes. The connection of Pro accumulation to cellular redox status or other factors, such as posttranscriptional mechanisms, that may regulate Pro metabolism has received relatively little attention. The extensive natural variation in Pro accumulation among Arabidopsis accessions (Kesari et al., 2012) is a promising resource to identify genes that affect Pro accumulation. Here, we conducted a GWAS of low water potential-induced Pro accumulation coupled with phenotyping of transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion mutants and overexpression lines. The major goals for this project were 2-fold: first, to test the utility of GWAS as a tool for the discovery of new Pro effector genes; and second, to evaluate heuristic methods for scoring and prioritizing candidate genes for subsequent validation. We both identified several new types of Pro effector genes that link Pro accumulation to cellular redox and energy status and demonstrated how even quite straightforward methods of sorting and ranking SNP data can increase the information that can be extracted from GWAS.

RESULTS

GWAS Analysis of Low Water Potential-Induced Pro Accumulation in Arabidopsis

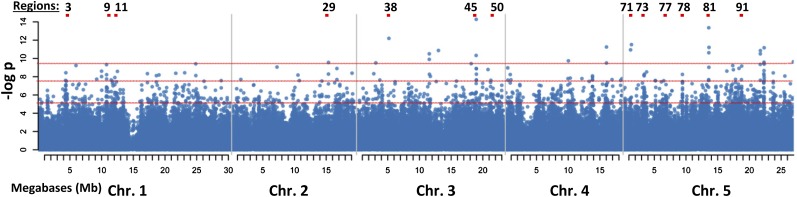

GWAS was performed using a data set of stress (−1.2 MPa for 96 h)-induced Pro levels covering 180 accessions in which there was nearly 10-fold variation between the highest and lowest levels of Pro accumulation (Supplemental Table S1; Kesari et al., 2012). Of this set of accessions, 133 have been genotyped using 250K SNP chips (Kim et al., 2007; Atwell et al., 2010) and were used in association analyses. The linear mixed model approach of Kang et al. (2008) was used to test the association of each SNP with log[Pro] while accounting for random effects correlated with kinship (average pairwise SNP identity in state). A Manhattan plot of genome-wide SNP P values (Fig. 1) shows that the SNPs with the most significant Pro association were distributed across several genomic regions.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of the SNP association with low water potential-induced Pro accumulation. Red lines indicates the P value cutoffs for the 1,000, 100, and 20 most significant (log P = −5.2, 7.6, and −9.5, respectively) SNPs used for subsequent scoring to identify regions of interest. Red blocks and numbers at the top indicate positions of the regions of interest that are shown in subsequent figures.

An arbitrary cutoff of the 1,000 SNPs of lowest P value (nominal P = 6 × 10−7 to 6 × 10−3) was used to define a gene list for further analysis (Supplemental Table S2). A gene was considered associated with one of these top 1,000 SNPs if any part of its untranslated region (UTR) or coding region was within 5 kb of the SNP. The list of SNP-gene associations generated using these criteria contained both multiple genes associated with one SNP and multiple SNPs associated with individual genes. Interestingly, there were few genes with known abiotic or stress-related functions based on our knowledge of the field. Some exceptions were the dehydrins XERO1 and XERO2 (LTI30), which were associated with the 14th ranked SNP, and the abscisic acid (ABA) catabolism gene CYP707A3, which was associated with the 34th ranked SNP (Supplemental Table S2). However, the insight that could be gathered from this list alone was limited, as it was not known which of the several candidate genes associated with each SNP actually affected Pro accumulation.

To prioritize this list of candidate genes, each gene associated with the top 1,000 SNPs was assigned a weighted score based on the number of top 1,000 SNPs associated with that gene and the relative strength of the SNP association with Pro (Supplemental Table S3). Such a scoring system allowed us to incorporate both the number of SNPs associated with a gene and the relative strength of the association into a simple ranking. While we found this sorting scheme to be useful in selecting genes for analysis (see below), it should be stated that several aspects of this scheme were arbitrarily set, and other schemes with different criteria could also generate gene lists useful in guiding downstream analysis.

The genes with the greatest weighted scores had both a few strong SNP associations (top 100 or top 20 SNPs in terms of P value) as well as multiple SNPs in the top 1,000 (Table I; the full list of scores is shown in Supplemental Table S3). As the top 20 and top 100 SNPs were not clustered in a few locations but rather dispersed in many locations throughout the genome (Fig. 1; Supplemental Tables S2 and S3), the genes highly ranked by this scoring system were also scattered among many locations in the genome. However, because a single SNP often had multiple genes nearby, many of the genes with the top scores were contiguous (e.g. AT4G27720 and AT4G27730 or AT5G54920, At5G54930, and At5G54940; Table I). Thus, their high scores were driven by linkage disequilibrium with common SNPs, and likely only one of the genes in each of these clusters affects Pro accumulation. Some of the high-scoring genes seem unlikely to influence Pro (such as the pseudogene AT3G29725 or the transposable element AT3G29727; Table I), suggesting that either the real driver of the low SNP P values may be a nearby gene not included in the window used to match genes with those SNPs, that there is a gene either not present or unannotated in the Col genome that is driving the association, or that it is a spurious association.

Table I. Top scoring genes using a weighted scoring system based on the number of top 1,000, top 100, and top 20 SNPs associated with each gene.

The complete list of top 1,000 SNPs (based on P value) and their associated genes is shown in Supplemental Table S2, and the scores for each gene with regions of interest marked are shown in Supplemental Table S3. SNP plots for each region of interest are shown in Supplemental Figure S1.

| Gene | Top 1,000 SNPs | Top 100 SNPs | Top 20 SNPs | Score | Region | Gene Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT4G27720 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 34 | 63 | Major facilitator superfamily |

| AT3G29725 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 33 | 40 | Pseudogene |

| AT3G29727 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 33 | 40 | Transposable element |

| AT4G27730 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 32 | 63 | Oligopeptide transporter6 |

| AT5G54920 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 31 | 97 | Unknown |

| AT5G54930 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 97 | AT hook motif protein |

| AT5G54940 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 30 | 97 | Translation initiation factor family |

| AT5G54950 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 29 | 97 | Aconitase family |

| AT5G54960 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 29 | 97 | Pyruvate decarboxylase2 |

| AT5G55040 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 28 | 98 | DNA-binding bromodomain |

| AT4G27700 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 27 | 63 | Phosphatase |

| AT4G27710 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 27 | 63 | CYP709B3 |

| AT1G30473 | 15 | 2 | 0 | 25 | 9 | Heavy metal transporter |

| AT3G51050 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 45 | FG-GAP repeat protein |

| AT3G51090 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 46 | Unknown |

| AT3G51100 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 46 | Unknown |

| AT3G51110 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 25 | 46 | Tetratricopeptide repeat |

| AT4G27690 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 25 | 63 | Vacuolar sorting protein26B |

| AT1G30470 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 9 | SIT4 phosphatase-associated family |

| AT2G36632 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 29 | Unknown |

| AT2G36640 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 29 | Embryonic cell protein63 |

| AT4G33240 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 65 | 1-Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate 5-kinase |

| AT1G30475 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 23 | 9 | Embryo-defective1303-like |

| AT2G36620 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 29 | RPL24 |

| AT2G36630 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 29 | Sulfite exporter TauE/SafE family |

| AT2G36650 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 29 | Unknown |

| AT5G35360 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 81 | Biotin carboxylase subunit |

| AT5G53510 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 95 | Oligopeptide transporter9 |

| AT5G54970 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 97 | Unknown |

| AT3G51057 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 45 | Unknown |

| AT4G33250 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 65 | Translation initiation factor3k |

| AT5G35405 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 81 | ECA1 gametogenesis-related protein |

| AT5G53486 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 95 | Unknown |

| AT5G53487 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 95 | Pre-tRNA, tRNA-Gly |

| AT5G55020 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | 98 | MYB120 transcription factor |

| AT1G30480 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 9 | DNA damage-repair/toleration protein111 |

| AT5G54820 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 96 | F-box protein |

To further select candidate genes for analysis, we scanned the list of genes from the top 1,000 SNPs for scores greater than 3 (i.e. at least three top 1,000 SNPs or one top 100 SNP associated with that gene). We then used that gene as a starting point to define a block of contiguous genes having at least one association with a top 1,000 SNP (score of 1 or higher). This approach identified many regions of interest that contained clusters of significant SNPs and/or SNPs with especially low P values (Supplemental Table S3). SNP plots for each of these regions of interest are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. It can be hypothesized that many of these regions contain at least one gene affecting Pro accumulation. This scheme also showed clearly that the 41 high-scoring genes shown in Table I were from only 12 clusters of significant SNPs. We used reverse genetics for several of these regions to identify genes affecting Pro accumulation.

Use of T-DNA Mutants to Explore Regions with Strongly Significant SNPs Identifies Thioredoxins as Effectors of Pro Accumulation

While the SNP patterns in the regions of interest did not clearly identify single genes, they did in most cases indicate a small block of candidates. A few regions around low P value SNPs and/or containing clusters of moderately significant SNPs were selected as case studies for reverse genetic analysis. In total, we analyzed 55 T-DNA lines covering 36 genes (Table II). For each gene selected, we attempted to use multiple T-DNA lines containing exon insertions or, in a few cases, insertions close to the transcriptional start site; however, this was not possible in all cases. A full list of T-DNA lines used is given in Supplemental Table S4, and results of the statistical analysis of the T-DNA Pro data set are given in Supplemental Table S5.

Table II. Candidate genes analyzed by reverse genetics.

The weighted score, region, and number of T-DNA lines analyzed are shown for each gene along with the difference in Pro accumulation compared with the wild type after seedlings were exposed to −1.2 MPa for 4 d. Double and single asterisks indicate significant differences in Pro accumulation mutants compared with the Col wild type either with (**) or without (*) correction for multiple testing. A list of the T-DNA lines used is given in Supplemental Table S4, and details of the statistical analysis of mutant Pro data are given in Supplemental Table S5.

| Gene | Score | Region | T-DNA Lines Assayed | Pro Difference Versus Col | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1G13320 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13.2** | Protein phosphatase2A subunit A3 |

| AT1G16760 | 1 | – | 1 | −2.1 | UspA domain kinase |

| AT1G30470 | 24 | 9 | 2 | −3.6 | Phosphatase-associated SIT4 family |

| AT1G30473 | 24 | 9 | 1 | 1.8 | Heavy metal transporter |

| AT1G30480 | 20 | 9 | 1 | −2.5 | DNA damage-repair/toleration protein111 |

| AT1G30500 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 0.6 | Nuclear factor Y subunit A7 |

| AT1G30510 | 1 | 9 | 1 | −1.1 | Ferridoxin nitrate reductase2 |

| AT1G33290 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 9.3* | Nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase |

| AT1G54160 | – | – | 2 | 9.9* | Nuclear factor Y subunit A5 |

| AT2G36620 | 23 | 29 | 2 | 9.4* | RPL24 |

| AT2G36630 | 23 | 29 | 1 | −1.4 | Sulfite exporter TauE/SafE family |

| AT2G36640 | 24 | 29 | 1 | 4.1 | Embryonic cell protein63 |

| AT2G36650 | 23 | 29 | 1 | 3.6 | Unknown |

| AT3G15355 | 16 | 38 | 1 | 0.6 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme25 |

| AT3G15360 | 16 | 38 | 2 | 14.7** | TRX-M4 |

| AT3G51030 | 3 | 45 | 2 | −17.3** | TRX1 |

| AT3G51040 | 3 | 45 | 1 | 3.9 | Return to ethylene sensitivity1 homolog |

| AT3G51050 | 25 | 45 | 2 | 1.8 | FG-GAP cell adhesion protein |

| AT3G56120 | 6 | 48 | 2 | 5.3 | S-Adenosyl-l-Met-dependent methyltransferase10+ superfamily |

| AT3G58450 | 2 | 50 | 1 | 10.7* | UspA domain protein |

| AT4G04670 | 5 | 54 | 3 | −3.6 | S-Adenosyl-l-Met-dependent methyltransferase10+ superfamily |

| AT4G32950 | 1 | 64 | 1 | 2.8 | Protein phosphatase2C |

| AT4G33230 | 3 | 65 | 1 | −3.6 | Invertase family |

| AT4G33240 | 24 | 65 | 1 | 2.6 | 1-Phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate 5-kinase |

| AT5G04840 | 16 | 71 | 2 | 8.8* | bZIP transcription factor |

| AT5G20310 | 3 | 77 | 2 | 12.1** | UspA domain protein |

| AT5G26850 | 17 | 78 | 2 | −1.1 | Unknown |

| AT5G26860 | 13 | 78 | 1 | −10.6* | LON1 |

| AT5G35370 | 17 | 81 | 2 | −1.5 | S-locus lectin kinase |

| AT5G35380 | 16 | 81 | 1 | −9.3 | UspA domain kinase |

| AT5G35390 | 16 | 81 | 2 | 3.2 | Receptor-like kinase |

| AT5G46320 | 16 | 91 | 2 | 16.0** | MADS box |

| AT5G53000 | 1 | – | 1 | −6.7 | TAP4646 |

| AT5G54820 | 20 | 96 | 2 | 5.0 | F-box protein |

| AT5G63940 | 1 | 100 | 2 | 2.2 | UspA domain kinase |

| AT5G66090 | 1 | – | 1 | 7.3* | Unknown |

We chose several regions for analysis based on the presence of SNPs of lowest P value. Region 45 (Fig. 2A) contained the lowest P value SNP in this GWAS (Supplemental Table S2). This SNP was located in the intergenic region between AT3G51050 and AT3G51057, and both of these genes had very high scores in our ranking (Table I). However, other significant SNPs in this region were 10 to 15 kb upstream (Fig. 2A). We tested T-DNA mutants for three genes in the middle of this cluster of SNPs (AT3G51030, AT3G51040, and AT3G51050) and found that two T-DNA lines for AT3G51030 (THIOREDOXIN1 [TRX1]) had a more than 30% reduction in Pro accumulation at −1.2 MPa, while mutants of the other two genes had no effect (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the few SNPs genotyped within the promoter and coding regions of AT3G51030 did not show significant association. It is possible that the variation directly affecting TRX1 function is not represented on the 250K genotyping chip and that the highly significant SNPs that were genotyped are linked to this unknown variation. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other nearby genes also affect Pro and contribute to the significant SNP associations in this genomic region. Interestingly, another thioredoxin, TRX-M4, was associated with an SNP having the third lowest P value in our analysis, and mutants of this gene had higher Pro accumulation than the Col wild type (Fig. 2B). The fact that two thioredoxins had opposing effects on Pro accumulation was at first surprising; however, it was consistent with observations that trx1 and trx-m4 mutants also had different effects on growth at low water potential (see below). These data identified TRX1 and TRX-M4 as new effectors of Pro accumulation. We also found that mutants of an uncharacterized bZIP transcription factor associated with the fourth lowest P value SNP had higher Pro (Fig. 2C), although, in this case, the difference was only statistically significant before applying the correction for multiple testing.

Figure 2.

Thioredoxins and a bZIP transcription factor associated with the lowest P value SNPs are effectors of low water potential-induced Pro accumulation. A, The graph (left) shows a plot of SNP P values for a 50-kb interval surrounding region 45, which includes the lowest single SNP P value found in our analysis. A complete list of genes in this region is given in Supplemental Table S3. Gray shaded areas are genic regions (exons plus UTRs). The dashed line indicates the P value cutoff of the top 1,000 SNPs (P = 0.006). The graph (right) shows Pro accumulation for T-DNA mutants of candidate genes in region 45 (for details of the T-DNA lines used and statistical analysis, see Table I and Supplemental Tables S4 and S5). Pro data are plotted as the difference in Pro ±se between the mutant and the wild type (WT; for details of the analysis, see “Materials and Methods” and Supplemental Table S4). Double asterisks indicate a significant difference in Pro after correcting for multiple testing. Note that where multiple T-DNA lines were analyzed for a particular gene (Table II), the Pro data shown are combined data from all the T-DNA lines for that gene. B, SNP P values (left) and Pro accumulation for T-DNA mutants of candidate genes (right) in region 38, which contains the third lowest P value SNP in our analysis. Double asterisks indicate a significant difference in Pro after correcting for multiple testing. C, SNP P values (left) and Pro accumulation for T-DNA mutants of a candidate gene (right) in region 71, which contains the fourth lowest P value SNP in our analysis. The asterisk indicates a significant difference in Pro before correcting for multiple testing (for details, see text and Supplemental Table S4). FW, Fresh weight.

Genes Encoding the Universal Stress Protein A Domain Affect Pro Accumulation

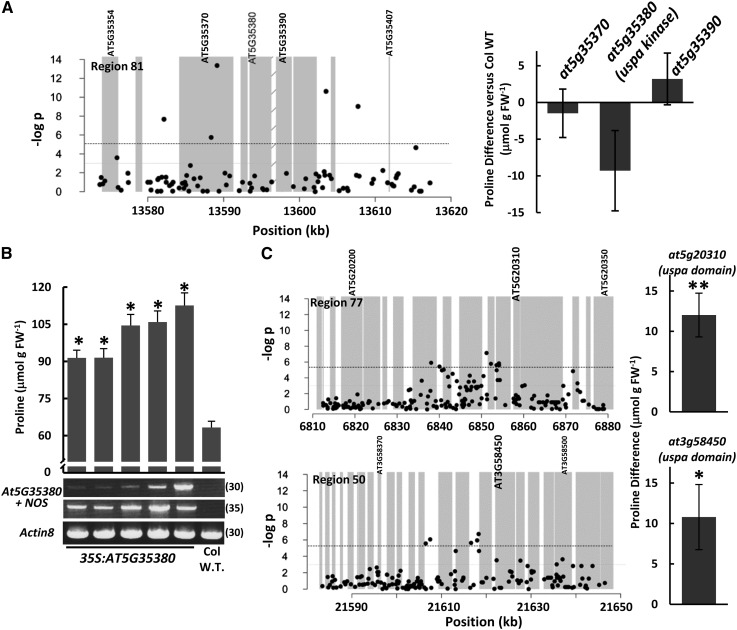

Region 81 contained the second lowest P value SNP in our analysis (Fig. 3A). Mutants of two of genes in this region clearly did not affect Pro accumulation, while mutant of the third gene (at5g35380) reduced Pro content by nearly 20% (Fig. 3A). This difference was marginally significant (nominal P = 0.08; Supplemental Table S5). AT5G35380 is a protein kinase with a Universal Stress Protein A (UspA) domain (Kerk et al., 2003). AT5G35380 was further investigated by generating transgenic lines with 35S-driven expression in the Col wild-type background. Homozygous T3 lines from five independent transformation events had Pro increased by 28 to 50 μmol g fresh weight−1 (144%–178% of the Col wild type; Fig. 3B). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR indicated that the extent of increase in Pro accumulation was roughly correlated to the level of transgene expression (Fig. 3B). Under unstressed conditions (−0.25 MPa), the transgenic lines had Pro levels indistinguishable from the wild type (data not shown). The combined data of T-DNA and transgenic lines established the UspA domain kinase AT5G35380 as an effector of low water potential-induced Pro accumulation.

Figure 3.

A UspA kinase and additional UspA proteins are effectors of low water potential-induced Pro accumulation. A, The graph (left) shows a plot of SNP P values for a 50-kb interval surrounding region 81, which contains the second lowest single SNP P value found in our analysis. A complete list of genes in this region is given in Supplemental Table S3. The graph (right) shows the Pro accumulation of T-DNA mutants of several candidate genes in region 81. Diagonal bars indicate the putative promoter region. Data presentation is as described for Figure 2. B, Low water potential-induced Pro accumulation in transgenic lines overexpressing the UspA domain kinase At5G35380. Asterisks indicate significantly different (P ≤ 0.01) Pro accumulation compared with the Col wild type (W.T.), which was used as the background for the transgenics. Data are means ± se combined from two independent experiments. The bottom panels show results of RT-PCR to verify the expression of the transgene. PCR was performed using primers specific to the transgene (gene-specific primer plus primer recognizing the NOS terminator present in the transgene construct). ACTIN8 was amplified as a loading control. Numbers at right indicate the number of PCR cycles performed. C, SNP plots for regions 50 and 77 along with Pro data for two UspA domain genes present in these regions. The data format is as described for Figure 2. Double asterisks indicate a significant difference in Pro after correcting for multiple testing, while the single asterisk indicates a difference significant only before correction for multiple testing.

Several other UspA proteins were also present in our GWAS data, although they were not associated with any individual SNPs of very low P value. Several of these genes were also tested using T-DNA mutants (Table II). Mutants of both AT5G20310 and AT3G58450 (Fig. 3C) had increased Pro accumulation. Both of these proteins have a UspA domain alone without fusion to a kinase domain, and interestingly, their effect on Pro accumulation was opposite that of the UspA kinase AT3G35380. These data indicated that multiple members, but not all, Arabidopsis UspA domain proteins are effectors of Pro accumulation. These data also indicated that not only SNPs of very low P value but also clusters of moderate P value SNPs could be used to find Pro effector genes.

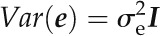

Additional Genes with Previously Unknown Effects on Pro Accumulation Were Identified by GWAS-Guided Reverse Genetics Based on Clusters of Moderately Significant SNPs

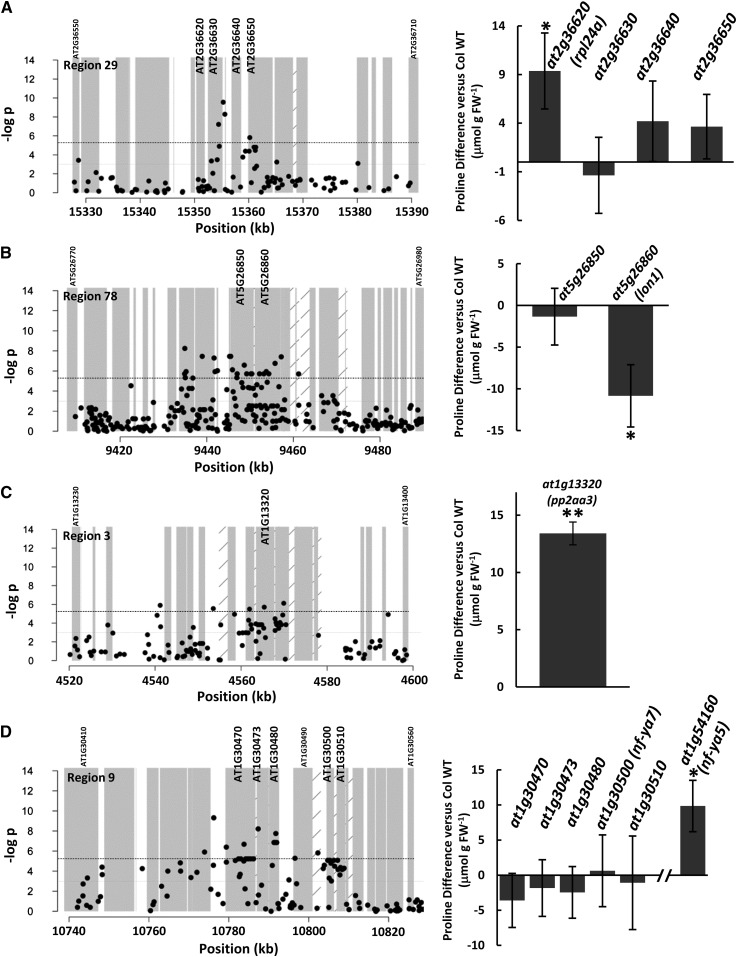

Additional regions of interest having clusters of moderate P value SNPs were analyzed as test cases to see if these also could be used to identify Pro effector genes. One such case was region 29, which contained a compact cluster of significant SNPs around AT2G36630 (Fig. 4A). However, reverse genetic analysis of four genes surrounding this cluster of significant SNPs found that two T-DNA mutants of AT2G36620 (RPL24A) had a more than 20% increase in Pro accumulation, while mutants of the other three adjacent genes, including AT2G36630, did not significantly differ from the wild type (Fig. 4A). This case suggested again how even when the SNP pattern seemed to mark a single gene, it may instead be a nearby gene that is driving the association. In this case, it is possible that the SNP or SNPs in RPL24A causing the Pro difference were not genotyped on the 250K SNP array and the other nearby SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium with this unidentified SNP or SNPs.

Figure 4.

Reverse genetic analysis of regions of interest identified by clusters of SNPs identifies additional effectors of Pro accumulation. Graphs (left) show SNP plots for different regions of interest identified by GWAS, and (right) show the difference in Pro accumulation compared with the wild type (WT) for T-DNA mutants of gene(s) within each region. Data presentation is as described for Figure 2. Complete lists of GWAS regions and genes in each region are given in Supplemental Table S2.

Region 78 was a somewhat contrasting example in that it had a diffuse band of SNP associations covering more than 20 kb (Fig. 4B). Within this 20-kb region was LON PROTEASE1 (LON1), a mitochondrial protease that affects mitochondrial function, root respiration, and growth (Rigas et al., 2009; Solheim et al., 2012). T-DNA mutation of LON1 led to reduced Pro accumulation, while mutation of an adjacent gene of unknown function had no effect (Fig. 4B). These data demonstrated an effect of LON1 on Pro accumulation; however, we do not rule out the possibility that other genes in region 78 could also have an effect, given the relatively wide band of SNP associations.

Region 3 (Fig. 4C) contained the protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit A3 (PP2AA3). Mutants of PP2A subunits or PP2A-associated regulatory proteins such as TAP46 have altered metabolism and responses to ABA and environmental signals (Kwak et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2006; Tseng and Briggs, 2010; Ahn et al., 2011). We found that pp2aa3 T-DNA mutants had increased Pro accumulation (Fig. 4C). In contrast, mutation of the PP2A-associated metabolic regulator TAP46 (Ahn et al., 2011) had no significant effect in the combined data of several experiments (Table II; Supplemental Table S5).

Similar to TAP46, it must be noted that some of our T-DNA analyses did not uncover any effects on Pro accumulation. Table II contains several such cases where our selected candidate genes did not show an effect, and region 9 (Fig. 4D) was a particular example. Region 9 had a fairly diffuse region of significant SNP associations covering nearly 20 kb and contained two interesting candidate genes. One was a member of the phosphatase-associated SIT4 family genes (AT1G30470), which was both close to a highly significant SNP and had a low mean P value of SNPs within its genic region (see below). The second was AT1G30500 (NF-YA7), which was of interest because its close homolog NF-YA5 has been reported to affect drought response (Li et al., 2008) and NF-Y factors more generally are thought to be involved in ABA and stress responses (Petroni et al., 2012). We isolated T-DNA mutants for NF-YA5 and found that they did have increased Pro accumulation (Fig. 4D); however, we found no effect on Pro accumulation in an NF-YA7 mutant (note that the genomic location of NF-YA5 is not close to NF-YA7; NF-YA5 was analyzed for comparison because of its previously reported effect on stress response). Likewise, mutants of several other genes in this region, including AT1G30470, also had no significant effect on Pro accumulation (Fig. 4D). It is possible that another gene in region 9 affects Pro accumulation, such as AT1G30490, for which we were unable to obtain suitable T-DNA mutants to test. Alternatively, natural variation may affect the function of one or more genes in this region in a way that is not replicated by knocking out the gene (i.e. gain-of-function or change-of-function variation rather than loss of function). Perhaps not surprising, this example also shows that the GWAS analysis does not find all genes affecting Pro: NF-YA5 was not associated with any of the top 1,000 SNPs. Possibly there was little natural variation in NF-YA5 among our panel of accessions.

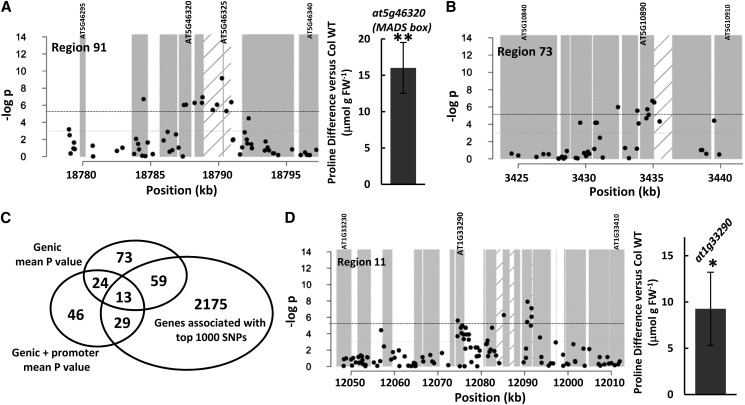

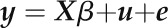

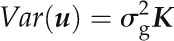

Mean P Values of Genic and Genic Plus Promoter Regions as an Alternative Ranking Method

While our ranking system took into account clusters of SNP associations, it was still biased toward SNPs of the lowest individual P values. As an alternative, we also looked for cases where the majority of SNPs within a gene or gene plus promoter had some association with Pro accumulation even if no individual SNP was strongly significant. This was done by identifying the 1,000 genes with the lowest mean P value of all SNPs within the genic region (UTRs, coding region, and introns; Supplemental Table S6) as well as the 1,000 genes with the lowest mean P value of all SNPs within the genic and putative promoter region (defined as 2 kb 5′ of the transcriptional start site; Supplemental Table S7). These two criteria were analyzed separately and then compared, because SNPs affecting gene function could be in either the coding region or the promoter, and it is unknown which criterion may be more effective in identifying candidate genes. Also, since the 250K chip genotyping does not cover all SNPs, it is possible that some genes would rank high in one criterion or the other simply because a few key SNPs were not genotyped. Two genes were in the top five for low mean P value of both genic and genic plus promoter SNPs: AT5G46320 (MADS box protein; Fig. 5A) and AT5G10890 (myosin heavy chain-related protein; Fig. 5B). These genes both had relatively low mean P values (0.002 and 0.006, respectively) across five to six SNPs in their genic plus 2-kb promoter regions. Two T-DNA lines of AT5G46320 had significantly higher Pro accumulation than the Col wild type (Fig. 5A). This gave an indication that the mean P value approach could identify Pro effector genes even though the individual SNPs in the promoter and coding region of AT5G46320 had only moderately significant P values. We were unable to obtain T-DNA lines of AT5G10890 for analysis. Other genes were in the list of low genic mean P values or genic plus promoter P values but not the other lists, because some simply had no SNPs genotyped in their genic regions while others had significant SNPs clustered in the genic region but none in the promoter (Supplemental Fig. S2). Thus, the distribution of genotyped SNPs clearly influenced the genes identified by the mean P value criteria.

Figure 5.

Candidate genes identified based on low mean SNP P values of genic or genic plus promoter regions. A and B, SNP P value plots of a 20-kb window surrounding two genes, AT5G46320 (A) and AT5G10890 (B), which were among to top five genes for low mean P value of both the genic (UTRs, exons, and introns) and genic plus promoter (2 kb 5′ of the transcriptional start site) regions. Complete lists of genes having low genic or genic plus promoter mean P values are given in Supplemental Tables S6 and S7, respectively. Diagonal bars indicate the 2-kb promoter region of the gene of interest. The graph (right) in A shows the Pro accumulation difference versus the Col wild type (WT) for T-DNA mutants of the MADS box gene AT5G46320. C, Venn diagram showing the intersection of genes having genic or genic plus promoter mean P ≤ 0.05 (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7) with the genes associated with the top 1,000 individual SNPs of low P value (Supplemental Table S2). SNP plots of the 13 genes in common for all three criteria are shown in Supplemental Figure S3. Lists of all genes in the overlapping categories along with their mean P values and scores are given in Supplemental Table S8. D, The graph (left) shows the plot of SNP P values for a 50-kb interval of region 11. The graph (right) shows the difference in Pro accumulation for T-DNA mutants of the nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase AT1G33290 compared with the Col wild type.

To further investigate whether these different ways of analyzing GWAS data identified unique or overlapping sets of candidate genes, we compared genes having low average P values in their genic or genic plus promoter regions with the genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs. For this comparison, an arbitrary cutoff of a mean genic or genic plus promoter P ≤ 0.05 was set. For the genic SNPs, 169 genes had mean P ≤ 0.05 while 112 genes had mean P ≤ 0.05 for SNPs in the genic plus 2-kb promoter region (Supplemental Tables S6 and S7). Thirteen genes had P ≤ 0.05 for both the genic and genic plus promoter analysis and were among the genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs (Fig. 5C; these genes are listed in Table III, and their SNP plots are shown in Supplemental Fig. S3). In particular, AT5G46320 and AT5G10890 (Fig. 5, A and B) had both relatively high scores in our scoring system as well as low mean genic and promoter P values (Table III). Overall, 35% to 40% of the genes with genic or genic plus promoter mean P ≤ 0.05 overlapped with the genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs (Fig. 5C; these genes are listed in Supplemental Table S8).

Table III. Genes having genic and genic plus promoter mean P ≤ 0.05 as well as an association with at least one top 1,000 SNP.

The 13 genes shown are from the intersection of all three parameters shown in Figure 5C. Genes from the intersection of genic P ≤ 0.05 or genic plus promoter P ≤ 0.05 with the top 1,000 SNPs (but not both) are shown in Supplemental Table S8.

| Gene | Genic SNPs | Genic Average P Value | Genic Plus Promoter SNPs | Genic Plus Promoter Average P Value | Score | Region | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1G01900 | 4 | 0.041 | 7 | 0.034 | 1 | – | Subtilisin-like Ser protease1.1 |

| AT1G54280 | 2 | 0.032 | 3 | 0.023 | 3 | 17 | ATPase E1-E2-type family protein |

| AT2G03770 | 2 | 0.030 | 6 | 0.033 | 1 | – | P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase family |

| AT2G28170 | 4 | 0.014 | 7 | 0.039 | 2 | – | Putative Na+/H+ antiporter7 |

| AT3G12970 | 2 | 0.017 | 2 | 0.017 | 1 | 37 | Unknown |

| AT3G46260 | 7 | 0.046 | 7 | 0.046 | 2 | – | Protein kinase |

| AT4G37880 | 8 | 0.029 | 9 | 0.039 | 1 | – | LisH/CRA/RING-U-box domain-containing protein |

| AT5G10010 | 3 | 0.031 | 4 | 0.024 | 2 | – | Unknown |

| AT5G10890 | 4 | 0.005 | 6 | 0.006 | 5 | 73 | Myosin heavy chain related |

| AT5G28150 | 4 | 0.042 | 7 | 0.047 | 2 | – | Unknown |

| AT5G44220 | 2 | 0.041 | 2 | 0.041 | 13 | 87 | F-box family protein |

| AT5G45350 | 8 | 0.018 | 15 | 0.037 | 4 | 89 | Pro-rich family protein |

| AT5G46320 | 2 | 0.001 | 6 | 0.002 | 16 | 91 | MADS box family protein |

As an example, two P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate genes had relatively low genic mean P values: AT2G03770 and AT1G33290 (Table III; Supplemental Table S6). We tested T-DNA mutants of AT1G33290, as its genic mean P value was based on a larger number of SNPs, and found significantly increased Pro accumulation (Fig. 5C). Thus, the mean P value criterion allowed us to identify another Pro effector gene. Combining the scoring system used here with mean P values can further prioritize candidate genes for analysis.

Overall, our analyses identified a set of mutants with increased and decreased Pro accumulation. This raised anew the question of whether the different Pro accumulation of these mutants would be accompanied by changes in low water potential tolerance. As a test of this idea, mutants of TRX1, TRX-M4 (Fig. 2), a UspA domain protein (Fig. 3C), and a MADS box gene (Fig. 5A), which all had substantial changes in Pro accumulation, were analyzed by measuring root elongation and seedling fresh weight after 10 d at low water potential as indicators of low water potential tolerance. Mutants of TRX1 grew more slowly than the wild type under either control or stress conditions (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). Thus, TRX1 may have pleiotropic effects on growth along with its effect on Pro. Conversely, TRX-M4 mutants had enhanced root elongation at low water potential (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). This may be consistent with the observation that trx-m4 had higher Pro (Fig. 2B). However, we cannot conclusively attribute the greater root elongation in trx-m4 to increased Pro, as we do not know what other processes are affected in these mutants. For the MADS box and UspA gene mutants, we found no significant difference in root growth and fresh weight compared with the wild type (Supplemental Figs. S4 and S5). Either the effect of these mutants on Pro metabolism was not strong enough or of the correct type (e.g. it was not specific to certain tissue or growing versus nongrowing cells) to significantly affect low water potential tolerance, there were other differences in the mutant that mitigated any effect of having higher or lower Pro, or, as we have noted previously (Sharma et al., 2011), the level of Pro accumulation is not always a strong indicator of stress tolerance.

DISCUSSION

The use of various reporters has made it possible to design forward genetic screens for changes in gene expression, protein localization, or cell structure in addition to visually apparent phenotypes. However, other phenotypes, such as stress-induced Pro accumulation, have remained difficult to analyze by forward genetic screening, as repeated destructive assays are needed to reliably quantify Pro levels. GWAS coupled to reverse genetics enabled a broad search for genes influencing Pro accumulation and led to the discovery of several genes not previously suspected to have any connection to Pro metabolism. The use of scores and mean P values to examine the data shifted the emphasis away from a few SNPs with lowest P values and allowed a broader range of candidate genes to be discovered. This study indicates that a combined GWAS and reverse genetics approach can be a viable alternative to genetically analyze traits that can only be measured in destructive assays. The Pro effector genes discovered here also give new biological insight into the stress resistance function of Pro accumulation by showing a connection of Pro accumulation to redox- and metabolism-related genes.

Discovery of New Mutant Phenotypes by Combined GWAS/Reverse Genetics

Concerns about the usefulness of GWAS data have included the possibility of false-positive associations and concerns that only the strongest and most significant GWAS hits would have large enough phenotypic effects to be of interest for further study. Our approach exploits the additional information contained in the spatial relationships among SNPs and builds on previous approaches that focus on individual SNPs (Filiault and Maloof, 2012). We found a number of Pro effector genes that would have been missed by only looking at individual SNPs of low P value. For example, the MADS box gene AT5G46320 had a strong effect on Pro accumulation and was highly ranked in our scoring and mean P value analyses. However, the most significant single SNP associated with AT5G46320 was ranked 30th (Supplemental Table S2). It is unlikely that this gene would have been selected for analysis based solely on individual SNP P values. Similar statements can be made about the P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate AT1G33290 (lowest P value SNP is ranked 671st) and the LON1 protease AT5G26850 (lowest P value SNP is ranked 120th). Additional analysis guided by the regions of interest and mean P values would likely identify many more such examples. The region-based approach and testing of several contiguous genes using T-DNA mutants also allowed us to deal with the fact that, in some cases, the SNPs with the lowest P value were in intergenic regions or several kilobases away from the gene found to affect Pro accumulation (as in Figs. 2A and 3A). Calculation of mean genic and genic plus promoter P values was also effective in finding some promising candidate genes not highly ranked by the scoring approach. One caveat is that the mean genic and genic plus promoter P values effectively penalize for the presence of nonsignificant SNPs in the gene body or promoter. These nonsignificant SNPs may be functionally silent and simply not linked to any functional SNP in the panel of accessions (or some may be false negatives). Thus, low mean genic or genic plus promoter P values can be used to find additional candidates, but high mean P values should not be used to exclude candidates identified based on the scoring system or strongly significant individual SNPs.

For the second concern of effect size, our data show that even moderately significant GWAS hits (i.e. only a few SNPs associated with Pro or only moderately significant P values) could be used to find mutants with substantial effects on Pro accumulation. This at first seems surprising, since it would be thought that large effects on Pro would lead to strong associations in the GWAS. In these cases, it is likely that none of the naturally occurring alleles lead to a complete loss of gene function; hence, the effect of these natural alleles on Pro accumulation is less than that of the T-DNA mutants. The opposite scenario may also be true, in that some of the naturally occurring alleles may cause increased expression or gain of function at the protein level. This effect would then not be recapitulated by the T-DNA mutants, leading to a false-negative result in the T-DNA testing of the GWAS data. This could be a factor, for example, in region 9 (Fig. 4D), where none of the T-DNA mutants tested had altered Pro accumulation. While it would be useful and interesting to understand how naturally occurring alleles alter gene expression, protein abundance, or protein function, our experience shows that when the main goal is to identify new effector genes for an unexplored trait, it is feasible to proceed directly to reverse genetic mutant analysis without the complexity of understanding the natural alleles.

Gene expression patterns or clustering of genes with similar expression patterns (e.g. using ATTED; http://atted.jp/) are often used to find candidates for reverse genetics. The use of GWAS to guide reverse genetics is complementary to such approaches in that it does not rely on gene expression patterns to identify candidate genes. Instead, natural variation can affect protein function without affecting gene expression. Although GWAS and gene expression patterns have been used together to identify candidate genes (Filiault and Maloof, 2012; Yano et al., 2013), our results suggest that the use of GWAS by itself may be useful in identifying genes acting at the posttranscriptional or posttranslational level. Several of the new Pro effectors identified here, including ribosomal protein (RPL24), protease (LON1), and UspA proteins, may all be hypothesized to affect Pro accumulation at the translational level (RPL24) or by posttranslational protein modification. Several additional regions contain ribosomal proteins (regions 44, 62, 72, 74, 77, 91, 94, and 101; Supplemental Table S3), including some with very high scores (Table I), which can now be investigated for effects on Pro accumulation and, possibly, translation of Pro metabolism proteins. These are promising findings, as little is known about the regulation of Pro accumulation beyond the transcriptional level.

Interestingly, the stress-induced Pro synthesis gene P5CS1 was not found in any of our lists of SNP associations or mean P values. Two SNPs adjacent to P5CS1 had P values that were low but missed the cutoff for the top 1,000 SNPs (16,595,258 bp on chromosome 2, P = 0.010 and chromosome 2 16,593,490 bp, P = 0.013), indicating that only a very weak GWAS signal was detected for P5CS1. This may seem in contrast to our previous report that variation in P5CS1 splicing was a main driver of natural variation in Pro accumulation (Kesari et al., 2012). However, the varying intron 2 TA repeats primarily responsible for P5CS1 alternative splicing are not found in the Arabidopsis 1,001 genomes database (presumably because sequencing reads with different numbers of TA repeats from the Col reference were discarded) and also are not present in the chip-based genotyping data used in this analysis. If no SNPs strongly linked to this P5CS1 variation were genotyped either, then this could explain how P5CS1 was not detected more strongly in our analysis. More generally, the genetic complexity of a trait, interaction between genes, and amount of variation that is present and genotyped can influence how strongly an association is detected in GWAS. Perhaps not surprisingly, no one genetic analysis can be expected to find all the effectors of Pro (or other traits).

GWAS Identifies Genes Connecting Pro Accumulation to Cellular Metabolic and Redox Status

The function of Pro in resistance to abiotic stress, particularly drought, has been a longstanding question in plant stress biology (Szabados and Savouré, 2010; Verslues and Sharma, 2010). Pro metabolism mutants have altered NADP-NADPH ratio at low water potential (Sharma et al., 2011) and increased reactive oxygen levels during salt stress (Székely et al., 2008), indicating a connection of Pro metabolism to cellular redox status. Also, the supply of extra reductant to plant tissue via a low level of dithiothreitol to change thiol-disulfide bonds caused specific changes in the metabolite profile, including increased Pro (Kolbe et al., 2006). However, genes involved in coordinating Pro accumulation with cellular metabolic or redox status have not been described, and GWAS-guided reverse genetics allowed us to identify several genes that may mediate such coordination to match Pro metabolism to stress severity and the metabolic status of the plant.

Consistent with such a connection of Pro to redox status and NADPH, TRX1 and TRX-M4 were found to be effectors of Pro metabolism associated with the SNPs of the lowest and third lowest P values, respectively, in the entire data set. TRXs reduce disulfide bonds of target proteins, thereby regulating protein activity or conformation (Meyer et al., 2009; König et al., 2012). Thioredoxins are themselves reduced either by thiordexin reductase, which utilizes NADPH, or in plastids by ferridoxin-dependent TRX reductase, which utilizes the same photosynthesis-derived reductant used to reduce NADP by ferridoxin NADP reductase (Meyer et al., 2009). Thioredoxins, as well as glutaredoxins, are known to regulate metabolism by targeting key enzymes whose activity needs to be coordinated with reductant supply, including Calvin cycle enzymes and Glc-6-P dehydrogenase of the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (Montrichard et al., 2009). Thus, the 20 TRX and 30 TRX-like proteins in Arabidopsis form a system to coordinate signaling and metabolism with cellular redox status (König et al., 2012). TRX-M4 was recently shown to regulate cyclic electron flow in chloroplasts (Courteille et al., 2013), and this is consistent with the idea that Pro synthesis may occur in or be associated with chloroplasts and serve to regenerate NADP+ for photosynthetic electron transport (Székely et al., 2008; Szabados and Savouré, 2010; Verslues and Sharma, 2010; Sharma et al., 2011). Regions 15 and 47 also contain thioredoxin genes, and region 73 contains CYSTATHIONINE β-SYNTHASE DOMAIN-CONTAINING PROTEIN3 (CBSX3). CBSX3 is one of several CBSX proteins that regulate the thioredoxin system (Yoo et al., 2011). Investigation of these genes may reveal additional details of the connection of Pro metabolism to redox status.

The effect of UspA mutants or overexpression lines on Pro accumulation also suggests a connection to cellular energy status. The UspA domain kinase AT5G35380 was associated with the SNP of the second lowest P value in our analysis, and mutants of two additional UspA proteins (without the kinase domain) also affected Pro accumulation. In bacteria, UspA domain proteins control stress responses and growth through adenine nucleotide binding and may act as switches that detect cellular energy or metabolic status (Persson et al., 2007; Drumm et al., 2009). Arabidopsis has large families of both UspA kinases and UspA proteins without kinase domains (Kerk et al., 2003). These proteins are now annotated as “adenine nucleotide α-hydrolase-like superfamily protein,” although whether all of them bind or hydrolyze ATP has not been reported. There is little functional information on these proteins in plants, although one recent transgenic study did suggest a role for a UspA protein in drought resistance (Loukehaich et al., 2012). The increased Pro accumulation in mutants of the nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase AT1G33290 also suggests a link of Pro accumulation to energy status; however, the functions of these proteins are even less understood than those of the UspA domain proteins.

Mutants of the MADS box, AGAMOUS-like gene AT5G46320 (Fig. 5A) had strongly increased Pro accumulation. MADS box proteins form homodimers and heterodimers that have DNA-binding activity and function in transcriptional regulation (de Folter et al., 2005). Whether this MADS box protein, as well as the bZIP transcription factor AT5G04840 (Fig. 2C), are direct transcriptional regulators of Pro metabolism genes will be of interest for future study. Other bZIP transcription factors are well known to regulate PDH1 expression in response to exogenous Pro and darkness-induced starvation (Satoh et al., 2002; Dietrich et al., 2011). Regions 14, 75, and 78 also contained MADS box/AGAMOUS-like genes, and region 51 contained another bZIP protein (bZIP54/G-BOX BINDING FACTOR2).

Of the other new Pro effector genes identified, lon1 mutants have been found to have reduced growth, changes in mitochondrial morphology, and altered abundance of a range of mitochondrial proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Rigas et al., 2009; Solheim et al., 2012). These effects are likely caused by a combination of protease and chaperone activity of LON1. The mitochondrial localization of LON1 suggests that it may affect mitochondrial Pro catabolism; however, an altered abundance of Pro catabolism enzymes was not observed in proteomic analysis of mitochondrial proteins in lon1 mutants (Solheim et al., 2012). As these experiments were performed on unstressed plants, it will be of interest to see if LON1 affects Pro metabolism in a stress-specific manner or if the altered Pro in lon1 is an indirect consequence of the broadly altered mitochondrial metabolism in lon1. Likewise, the effect of pp2aa3 on Pro accumulation could be either direct or indirect. Of the three genes (RCN1, PP2AA2, and PP2AA3) encoding PP2A regulatory A subunits in Arabidopsis, RCN1 has the dominant role in regulating several hormone and developmental responses (Kwak et al., 2002; Larsen and Cancel, 2003; Zhou et al., 2004; Blakeslee et al., 2008; Tseng and Briggs, 2010), with relatively little function detected for PP2AA3. This may suggest a more specific role of PP2AA3 in Pro metabolism or stress response.

This discussion of the many new genes found to affect Pro and the overall finding that more than 100 genomic regions had substantial signal in the GWAS begs the question of whether these genes are all direct regulators of Pro accumulation. The distribution of GWAS signal among many genomic regions also would seem to differ from, for example, the results of Riedelsheimer et al. (2012), who performed GWAS based on abundances of several secondary metabolites and the amino acids Lys and Tyr. They found only one to three regions per metabolite containing the SNPs of lowest P value. Similarly, GWAS analysis of tissue cadmium content found a single strong GWAS peak (Chao et al., 2012). It is possible that Pro accumulation at low water potential produces a more diffuse signal in GWAS because it is affected by many factors, including stress signaling, redox status, ABA, and general mechanisms coordinating amino acid and nitrogen metabolism pathways that lead to a more classic polygenic architecture (Verslues and Sharma, 2010; Sharma et al., 2011). Thus, many of the genes identified in GWAS likely affect Pro accumulation indirectly via broader changes in metabolism or redox status. We have deliberately referred to these genes as effectors of Pro accumulation rather than regulators, as the underlying molecular mechanisms have yet to be established.

Regardless of whether these genes are direct or indirect effectors of Pro metabolism, the above discussion illustrates that the GWAS and reverse genetics approach generated new insight into the biology of Pro accumulation and its role in stress resistance. GWAS identified many genomic regions each likely to have at least one gene affecting Pro accumulation. This represents a trove of information that can be mined in future experiments to understand the role of Pro in stress resistance. Now that the method is established, additional regions of interest can be tested systematically to find unexpected Pro effector genes. More broadly, our experience suggests that GWAS coupled with reverse genetics in Arabidopsis is a relatively untapped resource for exploring the biology of other traits and may be especially applicable to phenotypes, such as metabolite levels, where traditional forward genetic mutagenesis and screening is difficult to apply.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GWAS Mapping

We linked Pro accumulation phenotypic data (Supplemental Table S1; Kesari et al., 2012) to published genomic data on accessions from a 250K SNP chip (Kim et al., 2007; Atwell et al., 2010). Each Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) accession was genotyped with an array representing 250,000 biallelic SNPs, giving an average density of about one SNP per 500 bp. We removed SNPs that had a minor allele frequency of less than 0.1 in order to avoid spurious associations, resulting in a total of 173,382 SNPs (version 3.04 of SNP quality control; Atwell et al., 2010).

The association between each SNP and Pro accumulation was tested using a linear mixed-effects model, with a random effect of kinship included to attempt to control for population structure (Kang et al., 2008; Atwell et al., 2010). A kinship matrix was generated using the identity in state of SNPs between each pair of accessions (Atwell et al., 2010). Pro content was log transformed in order to improve normality. We implemented the efficient mixed-model algorithm of Kang et al. (2008) with the phenotype modeled as a function of SNP allelic state and correlated random effects:

|

(1) |

where y is the n × 1 vector of observed phenotype data for each accession (total of n accessions), X is an n × q matrix of data for q fixed effects, consisting of intercept and SNP effects, and β is a q × 1 vector giving the slope of the fixed effects. Correlated random effects are represented by u, an n × 1 vector:

|

(2) |

with K, the n × n kinship matrix, determining the correlation among accessions. The e term gives the random error of each accession:

|

(3) |

Statistical tests were implemented in R statistical computing software.

To prioritize genes and genomic regions, a list of genes associated with the 1,000 SNPs of lowest P value was generated. A gene was considered to be associated with an SNP if any part of its gene body (UTRs, exons, and introns) was within 5 kb of that SNP. For each gene appearing in this list, a count was made of how many top 1,000 SNPs, top 100 SNPs, and top 20 SNPs (based on lowest SNP P value) were associated with that gene. To identify and prioritize genes associated with either SNPs of low P value or multiple SNPs of moderate P value (or both), a score was generated consisting of 1 point for each top 1,000 SNP, 5 additional points for each of these SNPs that was in the top 100, and 10 additional points for each top 20 SNP. For each case where a gene exceeded a threshold score of 3 (at least three top 1,000 SNPs or one top 100 SNP associated with that gene), a “region” was started and extended to encompass all contiguous genes associated with at least one top 1,000 SNP. This procedure identified 101 regions of interest (Supplemental Table S3; Supplemental Fig. S1).

Also, mean P values of the genic region (UTRs, exons, and introns) or genic plus promoter (defined as the 2 kb 5′ of the transcriptional start site) were calculated across the genome. Lists of the 1,000 genes having the lowest genic or genic plus promoter mean P values were compiled and used for comparison with the scores and list of genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs as described in “Results.” Gene models used to calculate average genic and genic plus promoter P values were based on The Arabidopsis Information Resource 10 (www.arabidopsis.org).

T-DNA Analysis and Pro Phenotyping

T-DNA mutants were genotyped using primer sets generated by the Signal Web resource (http://signal.salk.edu/). Any lines for which the PCR genotyping was ambiguous or for which homozygous mutants could not be found were discarded from the analysis. Homozygous T-DNA mutants were grown to maturity to generate seed, and Pro analysis of T-DNA lines was performed using the same procedure as that used to generate the accession Pro data set used for the GWAS (Kesari et al., 2012). Seedlings were grown on control medium (one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium with MES buffer, pH 5.7, no sugar added) for 7 d and then transferred to −1.2-MPa polyethylene glycol-infused agar plates (Verslues et al., 2006). Two genotypes were grown together on a single agar plate, and two or three samples were collected per genotype. Several replicate experiments (incomplete blocks) were performed with each genotype represented in at least two blocks (the Col wild type was included in each block). For most T-DNA lines, this was performed using seed collected from several independently genotyped homozygous plants. Thus, for each T-DNA line, six to 24 Pro measurements were performed across several independent experiments. Samples for Pro analysis were collected 4 d after transfer to low water potential (−1.2 MPa). Pro analysis was performed by ninhydrin assay (Bates et al., 1973) adapted to a 96-well plate format (Verslues, 2010).

The entire T-DNA Pro data set was analyzed using a linear mixed-model approach with Proc Mixed in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute). The global model used included candidate genes and T-DNA insertion lines nested within candidate genes as fixed effects and a number of design factors (experimental block, Pro assay set, agar plate) as random effects. The significance of each candidate gene was evaluated using planned contrasts of each knockout genotype versus the Col wild type with the LSmeans statement and the difference option. The type 1 error rate (α = 0.05) for multiple testing was controlled using the simulate method in the LSmeans statement.

UspA Domain Kinase Overexpression Lines

At5g35380 complementary DNA without the stop codon was amplified from reverse-transcribed RNA isolated from stress-treated seedlings of the Col wild type using forward primer 5′-AAAAGCAGGCTTCATGGTGAGAACCTCCGAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGAAAGCTGGGTCAGATGTAGAACTGTTGTG-3′ (a second nested PCR was performed to add the remaining portion of the Gateway cloning sites) and cloned into pDONOR207 by BP reaction. The clone was moved to vector pGWB411 (Nakagawa et al., 2007), sequenced, and transformed into the Col wild type. Several independent transgenic lines having antibiotic resistance segregation ratios consistent with a single-copy insertion were advanced to the T3 generation, and homozygous lines were identified by antibiotic resistance. Expression of the transgene was verified by RT-PCR using a gene-specific forward primer and reverse primer specific to the NOS terminator of the vector (5′-ATGGTGAGAACCTCCGAGAA-3′ and 5′-AGACCGGCAACAGGATTCAATC-3′, respectively). Pro phenotyping of the transgenic lines was conducted as described above (each transgenic line was assayed in two independent experiments), and Pro data of the transgenics were compared with the Col wild type using Student’s t test.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. SNP P value plots of 101 regions of interest containing at least one gene with a score of 3 or higher.

Supplemental Figure S2. Additional genes from the top five genes with the lowest genic or genic plus promoter mean P value.

Supplemental Figure S3. SNP P value plots of 20-kb intervals containing the 13 genes having both genic and genic plus promoter mean P ≤ 0.05 and association with at least one of the top 1,000 individual SNPs of low P value.

Supplemental Figure S4. Root elongation and fresh weight of T-DNA mutants of selected genes.

Supplemental Figure S5. Representative seedlings of the wild type or mutants after transfer to either control or low water potential (−1.2 MPa) treatments.

Supplemental Table S1. Data set of Pro contents used for GWAS.

Supplemental Table S2. Genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs from GWAS of Pro accumulation.

Supplemental Table S3. Scoring of genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs and defining regions of interest.

Supplemental Table S4. T-DNA insertion lines used in this study.

Supplemental Table S5. Pro contents and statistical analysis of T-DNA mutants.

Supplemental Table S6. Mean genic P values.

Supplemental Table S7. Mean genic plus promoter P values.

Supplemental Table S8. Intersection of low genic and genic plus promoter P values with genes associated with the top 1,000 SNPs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ravi Kesari for assistance with T-DNA lines and transgenic plants, the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center for distribution of T-DNA lines and Arabidopsis natural accessions, and Trent Chang for laboratory assistance.

Glossary

- Col

Columbia

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- GWAS

genome-wide association

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- T-DNA

transfer DNA

- UTR

untranslated region

- ABA

abscisic acid

- RT

reverse transcription

References

- Ahn CS, Han JA, Lee HS, Lee S, Pai HS. (2011) The PP2A regulatory subunit Tap46, a component of the TOR signaling pathway, modulates growth and metabolism in plants. Plant Cell 23: 185–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann SM. (2013) Natural variation in abiotic stress and climate change responses in Arabidopsis: implications for twenty-first century agriculture. Int J Plant Sci 174: 3–26 [Google Scholar]

- Atwell S, Huang YS, Vilhjálmsson BJ, Willems G, Horton M, Li Y, Meng DZ, Platt A, Tarone AM, Hu TT, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association study of 107 phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana inbred lines. Nature 465: 627–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. (1973) Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 39: 205–207 [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson J, Roux F. (2010) Towards identifying genes underlying ecologically relevant traits in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet 11: 867–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee JJ, Zhou H-W, Heath JT, Skottke KR, Barrios JAR, Liu S-Y, DeLong A. (2008) Specificity of RCN1-mediated protein phosphatase 2A regulation in meristem organization and stress response in roots. Plant Physiol 146: 539–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchabke O, Chang FQ, Simon M, Voisin R, Pelletier G, Durand-Tardif M. (2008) Natural variation in Arabidopsis thaliana as a tool for highlighting differential drought responses. PLoS ONE 3: e1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao DY, Silva A, Baxter I, Huang YS, Nordborg M, Danku J, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Salt DE. (2012) Genome-wide association studies identify heavy metal ATPase3 as the primary determinant of natural variation in leaf cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet 8: e1002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courteille A, Vesa S, Sanz-Barrio R, Cazalé AC, Becuwe-Linka N, Farran I, Havaux M, Rey P, Rumeau D. (2013) Thioredoxin m4 controls photosynthetic alternative electron pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 161: 508–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Folter S, Immink RGH, Kieffer M, Parenicová L, Henz SR, Weigel D, Busscher M, Kooiker M, Colombo L, Kater MM, et al. (2005) Comprehensive interaction map of the Arabidopsis MADS box transcription factors. Plant Cell 17: 1424–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Marais DL, Juenger TE (2010) Pleiotropy, plasticity, and the evolution of plant abiotic stress tolerance. In CD Schlichting, TA Mousseau, eds, Year in Evolutionary Biology, Vol 1206. New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp 56–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Marais DL, McKay JK, Richards JH, Sen S, Wayne T, Juenger TE. (2012) Physiological genomics of response to soil drying in diverse Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Cell 24: 893–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich K, Weltmeier F, Ehlert A, Weiste C, Stahl M, Harter K, Dröge-Laser W. (2011) Heterodimers of the Arabidopsis transcription factors bZIP1 and bZIP53 reprogram amino acid metabolism during low energy stress. Plant Cell 23: 381–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumm JE, Mi KX, Bilder P, Sun MH, Lim J, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Basaraba R, So M, Zhu GF, Tufariello JM, et al. (2009) Mycobacterium tuberculosis universal stress protein Rv2623 regulates bacillary growth by ATP-binding: requirement for establishing chronic persistent infection. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiault DL, Maloof JN. (2012) A genome-wide association study identifies variants underlying the Arabidopsis thaliana shade avoidance response. PLoS Genet 8: e1002589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier-Level A, Korte A, Cooper MD, Nordborg M, Schmitt J, Wilczek AM. (2011) A map of local adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 334: 86–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock AM, Brachi B, Faure N, Horton MW, Jarymowycz LB, Sperone FG, Toomajian C, Roux F, Bergelson J. (2011) Adaptation to climate across the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Science 334: 83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juenger TE. (2013) Natural variation and genetic constraints on drought tolerance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Zaitlen NA, Wade CM, Kirby A, Heckerman D, Daly MJ, Eskin E. (2008) Efficient control of population structure in model organism association mapping. Genetics 178: 1709–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerk D, Bulgrien J, Smith DW, Gribskov M. (2003) Arabidopsis proteins containing similarity to the universal stress protein domain of bacteria. Plant Physiol 131: 1209–1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari R, Lasky JR, Villamor JG, Des Marais DL, Chen Y-JC, Liu T-W, Lin W, Juenger TE, Verslues PE. (2012) Intron-mediated alternative splicing of Arabidopsis P5CS1 and its association with natural variation in proline and climate adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 9197–9202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keurentjes JJB, Fu JY, de Vos CHR, Lommen A, Hall RD, Bino RJ, van der Plas LHW, Jansen RC, Vreugdenhil D, Koornneef M. (2006) The genetics of plant metabolism. Nat Genet 38: 842–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Plagnol V, Hu TT, Toomajian C, Clark RM, Ossowski S, Ecker JR, Weigel D, Nordborg M. (2007) Recombination and linkage disequilibrium in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet 39: 1151–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe A, Oliver SN, Fernie AR, Stitt M, van Dongen JT, Geigenberger P. (2006) Combined transcript and metabolite profiling of Arabidopsis leaves reveals fundamental effects of the thiol-disulfide status on plant metabolism. Plant Physiol 141: 412–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König J, Muthuramalingam M, Dietz KJ. (2012) Mechanisms and dynamics in the thiol/disulfide redox regulatory network: transmitters, sensors and targets. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Alonso-Blanco C, Vreugdenhil D. (2004) Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55: 141–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak JM, Moon JH, Murata Y, Kuchitsu K, Leonhardt N, DeLong A, Schroeder JI. (2002) Disruption of a guard cell-expressed protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit, RCN1, confers abscisic acid insensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14: 2849–2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PB, Cancel JD. (2003) Enhanced ethylene responsiveness in the Arabidopsis eer1 mutant results from a loss-of-function mutation in the protein phosphatase 2A A regulatory subunit, RCN1. Plant J 34: 709–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky JR, Des Marais DL, McKay JK, Richards JH, Juenger TE, Keitt TH. (2012) Characterizing genomic variation of Arabidopsis thaliana: the roles of geography and climate. Mol Ecol 21: 5512–5529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-X, Oono Y, Zhu J, He X-J, Wu J-M, Iida K, Lu X-Y, Cui X, Jin H, Zhu J-K. (2008) The Arabidopsis NFYA5 transcription factor is regulated transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally to promote drought resistance. Plant Cell 20: 2238–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Huang Y, Bergelson J, Nordborg M, Borevitz JO. (2010) Association mapping of local climate-sensitive quantitative trait loci in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 21199–21204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisec J, Meyer RC, Steinfath M, Redestig H, Becher M, Witucka-Wall H, Fiehn O, Törjék O, Selbig J, Altmann T, et al. (2008) Identification of metabolic and biomass QTL in Arabidopsis thaliana in a parallel analysis of RIL and IL populations. Plant J 53: 960–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisec J, Steinfath M, Meyer RC, Selbig J, Melchinger AE, Willmitzer L, Altmann T. (2009) Identification of heterotic metabolite QTL in Arabidopsis thaliana RIL and IL populations. Plant J 59: 777–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukehaich R, Wang T, Ouyang B, Ziaf K, Li H, Zhang J, Lu Y, Ye Z. (2012) SpUSP, an annexin-interacting universal stress protein, enhances drought tolerance in tomato. J Exp Bot 63: 5593–5606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JH, Shen GX, Yan JQ, He CX, Zhang H. (2006) AtCHIP functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase of protein phosphatase 2A subunits and alters plant response to abscisic acid treatment. Plant J 46: 649–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Y, Buchanan BB, Vignols F, Reichheld JP. (2009) Thioredoxins and glutaredoxins: unifying elements in redox biology. Annu Rev Genet 43: 335–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montrichard F, Alkhalfioui F, Yano H, Vensel WH, Hurkman WJ, Buchanan BB. (2009) Thioredoxin targets in plants: the first 30 years. J Proteomics 72: 452–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]