Abstract

Evolutionary changes in gene expression underlie many aspects of phenotypic diversity within and among species. Understanding the genetic basis for evolved changes in gene expression is therefore an important component of a comprehensive understanding of the genetic basis of phenotypic evolution. Using interspecific introgression hybrids, we examined the genetic basis for divergence in genome-wide patterns of gene expression between Drosophila simulans and Drosophila mauritiana. We find that cis-regulatory and trans-regulatory divergences differ significantly in patterns of genetic architecture and evolution. The effects of cis-regulatory divergence are approximately additive in heterozygotes, quantitatively different between males and females, and well predicted by expression differences between the two parental species. In contrast, the effects of trans-regulatory divergence are associated with largely dominant introgressed alleles, have similar effects in the two sexes, and generate expression levels in hybrids outside the range of expression in both parental species. Although the effects of introgressed trans-regulatory alleles are similar in males and females, expression levels of the genes they regulate are sexually dimorphic between the parental D. simulans and D. mauritiana strains, suggesting that pure-species genotypes carry unlinked modifier alleles that increase sexual dimorphism in expression. Our results suggest that independent effects of cis-regulatory substitutions in males and females may favor their role in the evolution of sexually dimorphic phenotypes, and that trans-regulatory divergence is an important source of regulatory incompatibilities.

Phenotypic evolution occurs both by changes to RNA and protein sequences and by changes in the level at which these molecules are expressed within cells. Evolution of gene regulation was hypothesized (Britten and Davidson 1969; King and Wilson 1975) and has been demonstrated to constitute an important component of divergence among species and variation within populations, including significant contributions to human disease (Carroll 2005; Wray 2007; Fay and Wittkopp 2008; Romero et al. 2012). Broadly speaking, gene regulation requires the activity of trans-acting factors, which directly or indirectly regulate gene expression via RNA or protein intermediates, and cis-acting sequences, which modulate localization of trans-acting factors to DNA and their effects on the expression of nearby genes. Studies of the genetic control of gene expression indicate that there is abundant variation within natural populations in both cis- and trans-regulation and that both modes contribute to adaptation and divergence between species (Wray 2007; Fay and Wittkopp 2008). However, cis- and trans-regulation have been hypothesized to differ in important genetic and evolutionary properties. First, cis-regulatory variants have been observed to have quantitatively larger effects on expression than trans-regulatory variants (Brem et al. 2002; Hughes et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2011; Gruber et al. 2012), although there are exceptions (Genissel et al. 2008; Emerson et al. 2010). Second, a greater proportion of cis-regulatory variants have additive effects on expression than trans-acting variants, which are more likely to be dominant or recessive (Wray 2007; Lemos et al. 2008a; McManus et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2011; Gruber et al. 2012). Third, cis-regulatory mutations have been hypothesized to have fewer pleiotropic effects than mutations in transcriptional regulators, which can affect the expression of hundreds of genes (Stern 2000). Because additive phenotypic effects increase the efficacy of selection and reduced pleiotropy can decrease deleterious side effects of mutations, it has been proposed that cis-regulatory changes will be enriched between species relative to their frequency within species (Lemos et al. 2008a; Wittkopp et al. 2008; Emerson et al. 2010). However, the relative contributions of cis- and trans-regulation to variation in gene expression within and among species vary extensively between studies (e.g., Li and Burmeister 2005), indicating that estimates of these quantities are influenced by either the genotypes or the methodologies used to measure them.

Gene regulation is central to the evolution and development of sexual dimorphism. As males and females of the same species carry the same genes (except for differentiated sex chromosomes), phenotypic differences between the sexes must result from differential expression of a single genome. Sexual dimorphism is a universal feature of dioecious animals, and estimates of the number of genes differentially expressed between adult male and female Drosophila melanogaster range from 4000 (Gnad and Parsch 2006) to more than 17,000 (Innocenti and Morrow 2010); however, allometric differences in tissue size relative to body size between males and females can give the appearance of sex-biased expression in the absence of sexually dimorphic transcription when expression is assayed from whole animals (Ranz et al. 2004). Mutations may have different selective effects in males and females, due to global differences between the sexes in gene regulation and chromatin environments (Liu et al. 2005; Gelbart and Kuroda 2009), sex-specific reproductive strategies (Lawson Handley and Perrin 2007), and the need to express genes in sex-specific cells such as the gonads (Chintapalli et al. 2007). A frequently cited model of the evolution of sexually dimorphic gene expression invokes such “sexually antagonistic” alleles that are beneficial in one sex but detrimental in the other (Rice 1984). The fixation of a secondary mutation that changes expression of the antagonistic allele in the disfavored sex could simultaneously resolve the fitness conflict and generate sexually dimorphic expression. Whole-genome expression analyses have claimed to identify sexually antagonistic phenotypes in Drosophila (Connallon and Knowles 2005; Innocenti and Morrow 2010); however, neither study determined the genetic basis of sexually dimorphic expression, leaving key aspects of this model untested (Fry 2010).

To identify the genetic basis for regulatory divergence between closely related species, we conducted a genome-wide expression analysis in introgression hybrids between two sister species of Drosophila. Previous studies of gene expression in interspecific hybrids of Drosophila have focused largely on the F1 generation, assayed gene expression in sterile hybrid animals, and been restricted to one sex (Ranz et al. 2004; Wittkopp et al. 2004; Moehring et al. 2007; Wittkopp et al. 2008; Graze et al. 2009; Lu et al. 2010; McManus et al. 2010). In contrast, we focus here on advanced generation hybrids between Drosophila simulans and Drosophila mauritiana, which produce fertile F1 females, allowing genetic material to be moved between these species. We used microarrays to measure gene expression in genotypes derived from an inbred strain of D. simulans except for a small region on the third chromosome that was introgressed from an inbred strain of D. mauritiana. Males and females of all genotypes used here are viable and fertile, allowing us to assay expression in (relatively) phenotypically normal adults of both sexes. Our study constitutes a fine-scale genetic analysis of interspecific divergence in genome-wide gene expression and allows us to measure the effects of divergent regulatory loci in both sexes. We find that divergent gene expression caused by the introgressed genomic segments act largely via trans-regulation, that cis- and trans-regulatory divergence differ in multiple aspects of inheritance, and that cis-regulatory divergence is enriched for sexually dimorphic effects on expression.

Results

Detecting divergent regulation in introgression genotypes

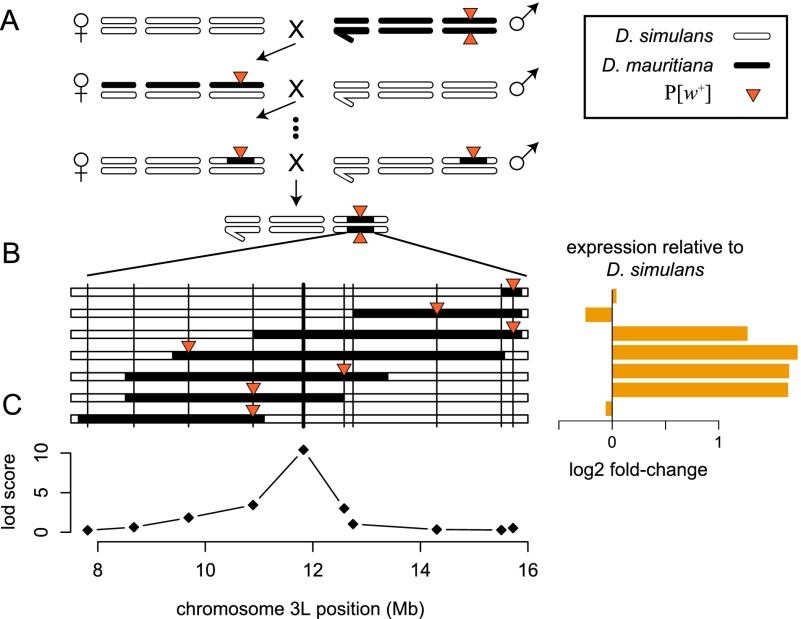

We assayed genome-wide gene expression using microarrays in virgin adult male and female flies of seven hybrid genotypes that introduce a combined ∼9.3 Mb on chromosome arm 3L from D. mauritiana into an otherwise D. simulans genetic background. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping identified genes that are differentially expressed between introgression genotypes and the parental D. simulans strain with expression phenotypes that are statistically significantly linked to a marker within the introgressed region (Fig. 1). We refer to genes with genetic evidence for regulatory differences between species as “divergently regulated.” Divergent regulation of genes located outside the introgressed region results from functionally divergent D. mauritiana alleles of trans-acting factors located within the introgressed region. Divergently regulated genes located within the introgressed region and close to a genetic marker linked to the regulatory effect are candidates for divergent cis-regulatory sequences.

Figure 1.

Approach used to map factors within the introgressed region that affect gene expression. (A) Genomic regions marked with a visible transgene (P[w+]) were introgressed from D. mauritiana into a D. simulans background. Bars indicate the sex chromosomes (left) and the two major autosomes. (B) Gene expression was assayed in adult males and females from seven genotypes carrying overlapping introgressions on chromosome arm 3L. Horizontal black bars indicate the extent of the introgressed segments, and vertical lines denote the location of genotyping markers. Expression levels in the seven homozygous introgression lines are shown to the right for an exemplar gene (Est-6). (C) QTL mapping identified marker loci within the introgressions where the D. mauritiana allele has a detectable effect on gene expression relative to the background D. simulans strain.

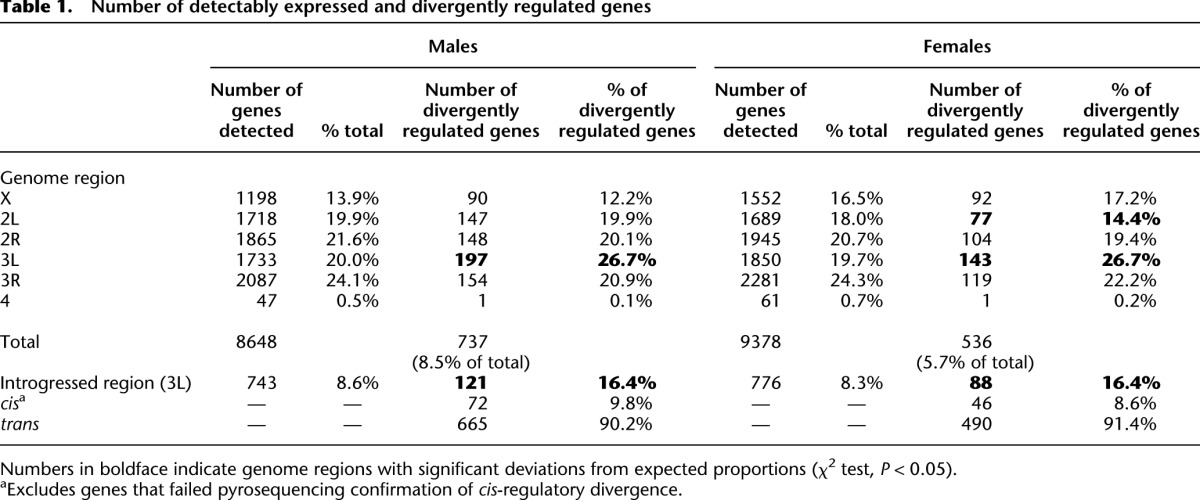

In both sexes, we observe a significant enrichment of divergently regulated genes located within the introgressed region (Table 1) resulting from cis-regulatory divergence between these two species. This inference was confirmed by measurements of allele-specific expression via pyrosequencing in introgression heterozygotes generated by crossing introgression genotypes to the parental D. simulans strain (see Methods). We measured allele-specific expression of 90 genes in males; 85 of these genes also gave reproducible results in females. Among all genes assayed for allele-specific expression, 76% and 71% showed significant differences in expression between the D. simulans and D. mauritiana alleles in males and females, respectively (Supplemental Table 1), indicating cis-regulatory divergence at these loci. The allele-specific ratios obtained from pyrosequencing and the effects estimated from the microarrays are similar (Supplemental Fig. 1; ρ = 0.744 and 0.719 in males and females, respectively; P < 0.0001). We excluded those genes where pyrosequencing failed to confirm the microarray results from our analyses of cis-regulatory divergence.

Table 1.

Number of detectably expressed and divergently regulated genes

Differentially expressed genes located within the introgressed region but unlinked from the genetic marker associated with the regulatory effect are regulated in trans. In males and females, respectively, 40% and 48% of divergently regulated genes located in the introgression are regulated in trans; however, many more introgressed genes are presumably divergently regulated by trans-factors located elsewhere in the genome. Genome-wide, we detect 665 genes in males and 490 genes in females that are divergently trans-regulated (Table 1) as a result of evolutionary divergence in a region comprising <10% of the Drosophila euchromatic genome.

Sexual dimorphism in divergent gene regulation

At a P-value of 2 × 10−4, which corresponds to a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.02 in males and 0.03 in females (see Methods), we detect 737 divergently regulated genes in males and 536 in females (Table 1), indicating that a significantly larger fraction of the genome is differentially expressed in males than in females as a result of the introgressed segments (χ2 = 126, P < 0.001). This excess in males is observed among genes regulated both in trans and cis, is robust to varying the FDR (Supplemental Table 2), and consists mainly of expression effects of small magnitude (Supplemental Fig. 2). Previous studies have shown that the expression of genes transcribed mainly or specifically in the testes diverges rapidly between species and is highly variable within species (Meiklejohn et al. 2003; Ranz et al. 2003; Zhang et al. 2007; Brawand et al. 2011). Although 100 genes divergently regulated in males are expressed specifically in testes in D. melanogaster (Chintapalli et al. 2007), testis-specific genes are not overrepresented among divergently regulated genes (χ2 = 2.40, P > 0.05) (Supplemental Table 3). Additionally, after excluding germline-specific genes, there remain significantly more divergently regulated genes in males than in females, indicating that the excess of divergent regulation seen in males cannot be solely attributed to rapid gene expression evolution in the male germline.

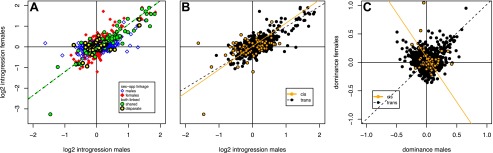

A large majority (∼80%) of genes detectably expressed in both sexes show significant divergent regulation in either males or females but not both (Supplemental Table 4). However, direct comparison of the homozygous effects of introgressed alleles on gene expression in males and females (Fig. 2A), regardless of the statistical significance of QTL linkage, suggests that requiring a significant association in both sexes overestimates the extent of genetic independence in divergent regulation between the sexes. In general, the largest expression effects are similar in males and females, and many of these genes may show significant QTL linkage in only one sex due to limited statistical power. Among genes with a smaller magnitude of divergent expression, the effects are largely independent in males and females; we observe few antagonistic genetic effects such that genes are up-regulated in one sex and down-regulated in the other (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Introgression effects on expression in males and females for 964 genes divergently regulated in at least one sex and expressed in both sexes. (A). Homozygous introgression effects (twice the additive effect estimated from Haley-Knott regression) relative to the parental D. simulans strain. Symbols indicate whether gene expression phenotypes show significant eQTL in only one sex (sex-spp) or both males and females (both linked), and among the latter group, whether the linked genetic marker in males and females is shared (the same or adjacent markers) or not (disparate markers). For genes with shared markers between the sexes, expression effects are strongly positively correlated (green dashed line, slope = 1.15, ρ = 0.90, P < 0.0001). (B) Homozygous introgression effects in males versus females for cis- and trans-regulated genes. (C). Dominance parameters for expression effects in males and females, for cis- and trans-regulated genes. Dominance parameters are weakly positively correlated for trans-regulated genes (ρ = 0.089, P = 0.008), and weakly negatively correlated among cis-regulated genes (ρ = −0.22, P = 0.046).

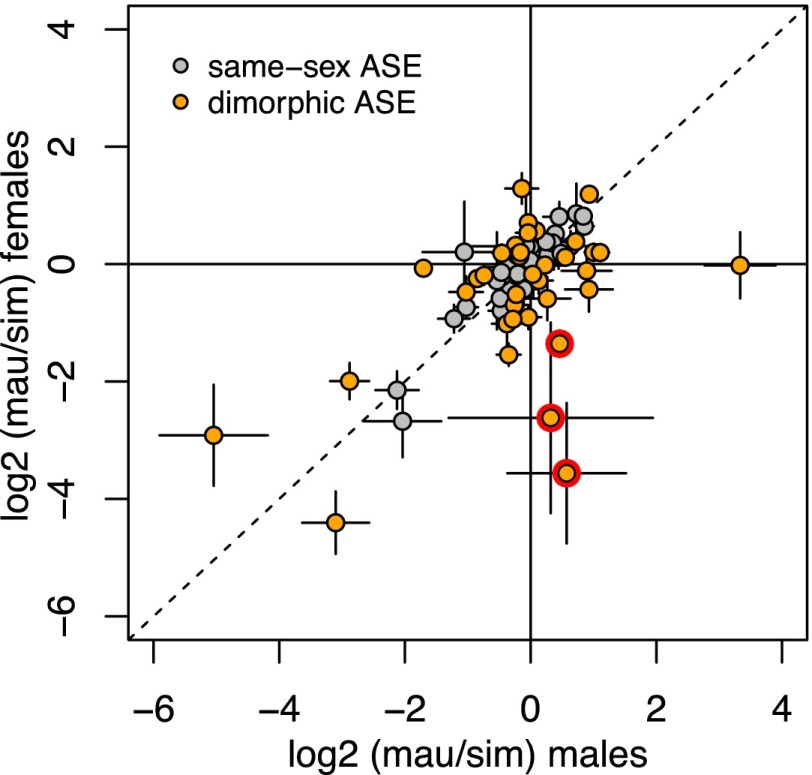

We compared ratios of allelic expression in males and females for the 85 genes assayed by pyrosequencing in both sexes. While allelic expression is overall positively correlated between males and females (Fig. 3; ρ = 0.586, P < 0.0001), 37 genes (44%) have ratios of allelic expression that significantly differ between the sexes (P < 0.02, FDR = 0.05). These differences are largely of degree, and the most extreme examples of sexually dimorphic allele-specific expression are genes with strong allelic biases in one sex and little bias in the other. These extreme cases include three genes with modestly but nonsignificantly elevated expression from the D. mauritiana allele in males, but strongly biased expression from the D. simulans allele in females (Fig. 3). These three genes are located in the same 262-kb chromosomal region (Fig. 4), and this clustering of genes with sex-reversed allele-specific expression is significantly different from random expectation (permutation test, P = 0.0025). This 262-kb region includes two additional genes that could not be assayed by pyrosequencing in females, but that show significantly greater expression from the D. mauritiana allele in males; four of these five genes are expressed exclusively in testes, and the fifth is accessory-gland specific in D. melanogaster. These observations suggest that cis-regulatory control of gene expression across much of this 262-kb region has diverged between these two species in a sex-specific manner.

Figure 3.

The ratio of expression from the D. mauritiana and D. simulans alleles in introgression heterozygotes is plotted for females versus males for 85 genes assayed by pyrosequencing. Three genes located in a region with sex-reversed allele-specific expression are outlined in red. Error bars indicate 95% confidence limits.

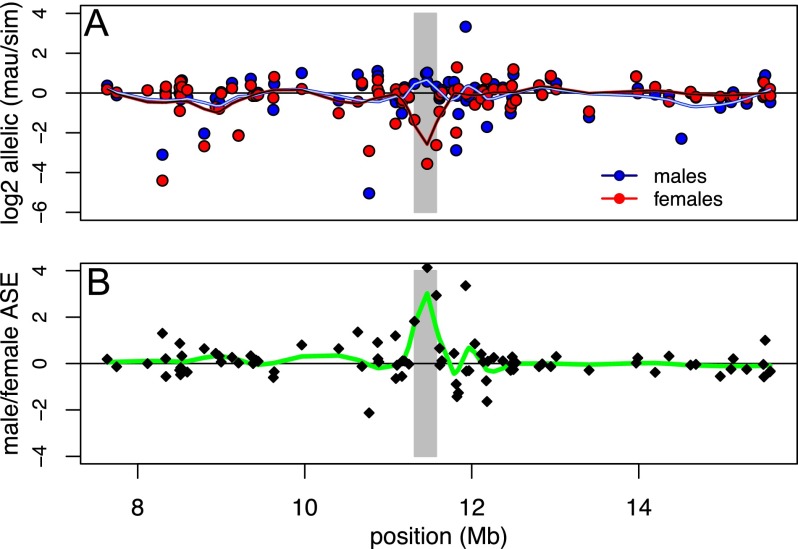

Figure 4.

Allele-specific expression among genes assayed by pyrosequencing within the introgressed region. (A) Log2 ratios of allelic expression (D. mauritiana/D. simulans) in males and females. Trend lines were obtained by loess smoothing using a span of 0.2. The candidate region containing local sexually dimorphic cis-regulatory effects is indicated in gray. (B) Differences in allelic expression between males and females as a function of location. The trend line was obtained by loess smoothing using a span of 0.2. The candidate region with sexually dimorphic cis-regulatory effects is apparent as a net excess of D. mauritiana allelic expression in males, due to strong overexpression of the D. simulans allele in females.

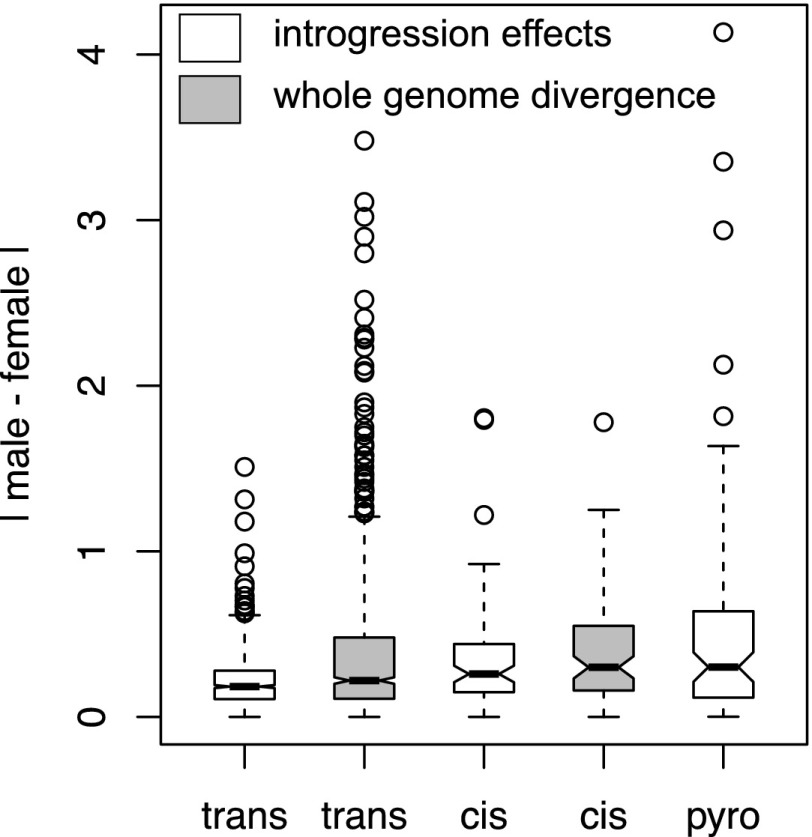

Among genes with significant QTL associations in at least one sex, we find that both the prevalence and magnitude of sexually dimorphic expression differs between cis- and trans-regulatory divergence (Fig. 2B). First, the proportion of genes with significantly different magnitudes of divergent regulation in males versus females (as assessed by nonoverlapping 95% confidence intervals) is greater in cis (55%) than in trans (36%) (Fisher’s exact test, PFET = 0.0009). Second, the median absolute value of the difference between males and females in divergent regulation is ∼1.4-fold greater among genes regulated in cis than in trans (Fig. 5; Mann–Whitney test, PMW < 0.0001). Greater sexual dimorphism is associated with larger expression effects (averaged over males and females), although this effect is weaker among divergently trans-regulated genes (ρ = 0.174, P < 0.0001) than it is among divergently cis-regulated genes (ρ = 0.544, P < 0.0001) or among the allele-specific expression ratios obtained from pyrosequencing (ρ = 0.487, P < 0.0001) (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Figure 5.

Introgressed cis-regulatory divergence generates greater sexual dimorphism in expression than introgressed trans-regulatory factors. (White boxes) The distribution of the absolute differences between males and females in the effects of introgressed factors measured by microarray, as well as the absolute difference between the sexes in allelic expression measured by pyrosequencing. (Gray boxes) The distribution of the absolute differences in expression between males and females resulting from whole-genome divergence between the parental simB and mau12 strains for the same genes.

In contrast to the homozygous effects of introgressed alleles (Fig. 2B), the dominance parameter estimates (Haley and Knott 1992) from the QTL analysis are largely independent between males and females (Fig. 2C), indicating that the effects of introgressed alleles are more similar between the sexes when homozygous than when heterozygous. However, as with the homozygous effects, dominance estimates are more disparate between males and females for introgressed cis-regulatory variants than factors acting in trans. There is a weak but statistically significant positive relationship between male and female dominance parameters among introgressed trans-factors (ρ = 0.089, P = 0.008), in contrast to a weak and marginally significant negative correlation between male and female dominance parameters associated with introgressed cis-regulatory divergence (ρ = −0.22, P = 0.046) (Fig. 2C). This indicates that, on average, expression effects of cis-regulatory divergence in introgression heterozygotes deviate from an additive expectation in the opposite direction in males and females.

Most gene expression traits are oligogenic or polygenic (Brem et al. 2002; Schadt et al. 2003; Brem and Kruglyak 2005; Gibson and Weir 2005); as a consequence, gene expression divergence between the parental simB and mau12 strains is expected to often result from the combined effects of divergence at multiple loci. Differences between the effects of introgressed factors (relative to simB) and the effects of genome-wide divergence in mau12 (relative to simB) indicate how the effects of introgressed factors on gene expression are modified by D. mauritiana alleles at other loci. We compared the extent of sexually dimorphic expression resulting from introgressed factors with estimates of sexually dimorphic expression between simB and mau12 at divergently regulated genes. Among genes divergently regulated by trans-factors, the effects of the introgressed factors are significantly less sexually dimorphic than the effects of whole-genome divergence (PMW < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). In contrast, the median magnitude of sexual dimorphism among divergently cis-regulated genes does not differ between introgression effects and whole-genome species divergence (PMW = 0.292). Furthermore, the median magnitude of sexual dimorphism due to whole-genome divergence is similar for genes regulated by introgressed cis- and trans-factors (PMW = 0.066). These observations suggest that D. mauritiana alleles outside the introgressed region decouple trans-regulatory effects in males and females more often than effects resulting from cis-regulatory divergence.

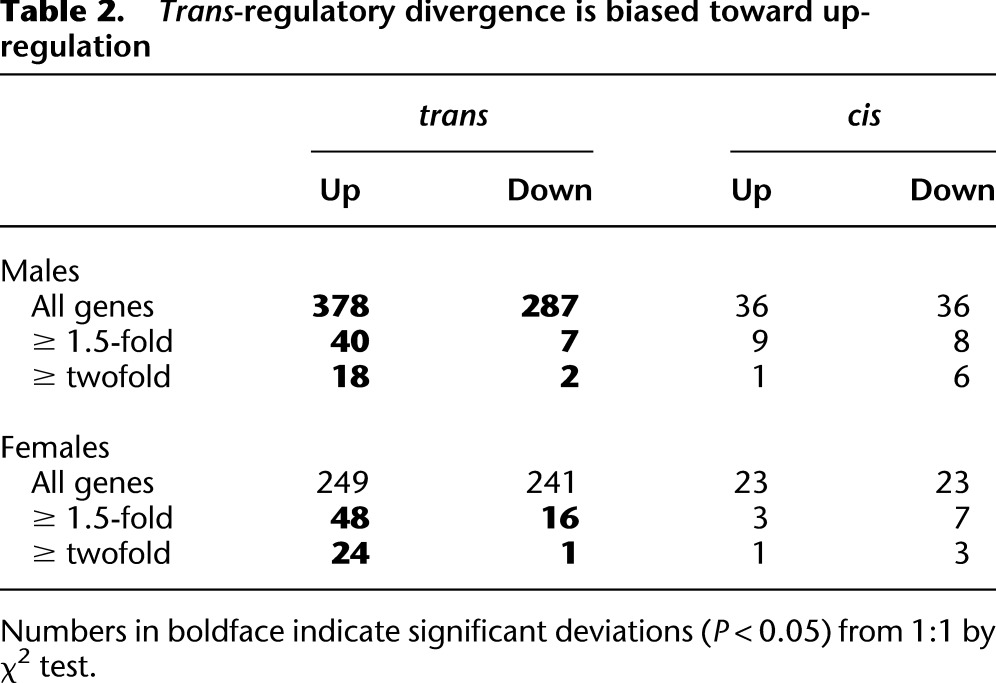

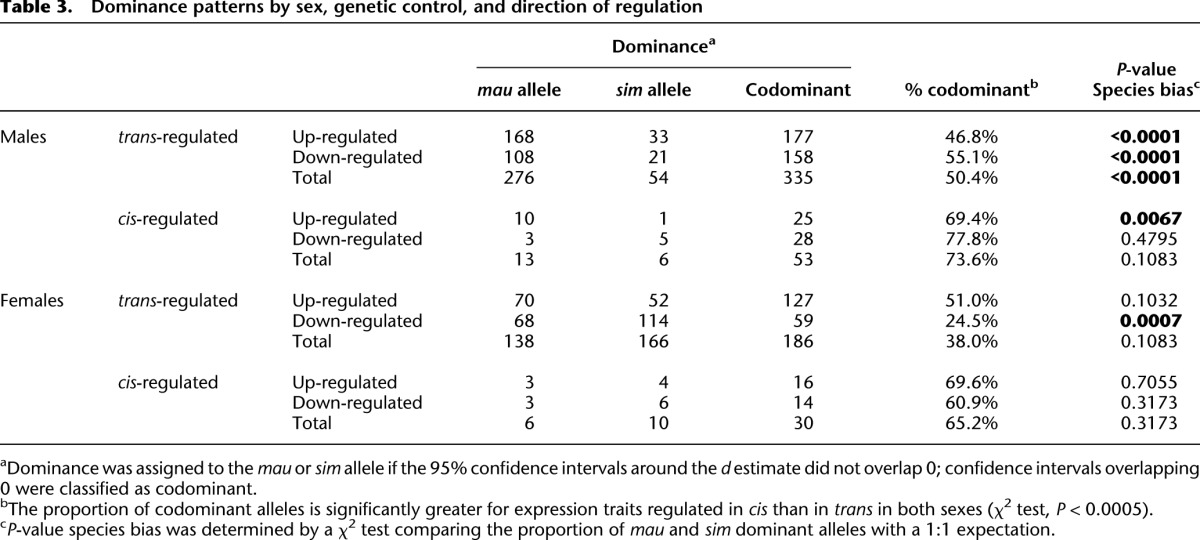

Divergent trans-regulation is enriched for dominant D. mauritiana alleles that cause up-regulation

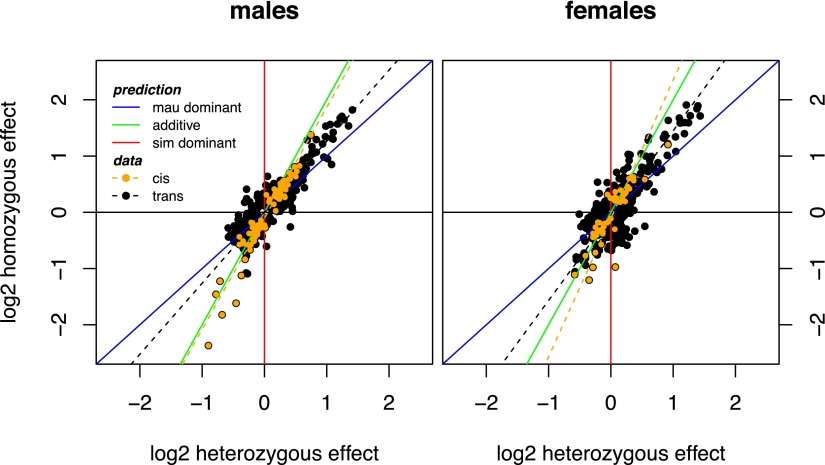

In addition to the differences in sexual dimorphism, cis- and trans-regulatory divergences differ substantially in other aspects of their inheritance and evolution between species. First, the magnitude of expression effects, as measured in fold-change, is significantly larger for cis-regulatory divergence than trans-regulatory divergence (Supplemental Table 5). Second, we observe that D. mauritiana alleles of trans-regulatory factors tend to up-regulate target genes, while there is no significant bias toward up- or down-regulation as a result of cis-regulatory divergence (Table 2). This bias is most pronounced among the largest expression effects, as 42/45 genes divergently trans-regulated twofold or more are up-regulated by D. mauritiana alleles. Third, in both sexes, the effects of cis-regulatory divergence are largely additive—the effects on expression in introgression heterozygotes are approximately half the effects in introgression homozygotes—whereas trans-acting factors are more often dominant (Fig. 6). Furthermore, among genes divergently regulated in trans, we observe a sex-by-species bias in dominance relationships; expression in introgression heterozygote males, but not females, is more similar to expression in introgression homozygotes than to simB, indicating that, in males, introgressed D. mauritiana alleles of trans-regulatory factors are more frequently dominant than their homologous D. simulans alleles (Table 3).

Table 2.

Trans-regulatory divergence is biased toward up-regulation

Figure 6.

Differential inheritance of gene expression phenotypes in cis versus in trans. Cis-regulation affects expression additively (males: slope = 1.97, ρ = 0.958; females: slope = 2.46, ρ = 0.817, P < 0.0001 in both sexes), while trans-regulation is associated with more dominant D. mauritiana alleles (males: slope = 1.26, ρ = 0.900; females: slope = 1.51, ρ = 0.809, P < 0.0001 in both sexes).

Table 3.

Dominance patterns by sex, genetic control, and direction of regulation

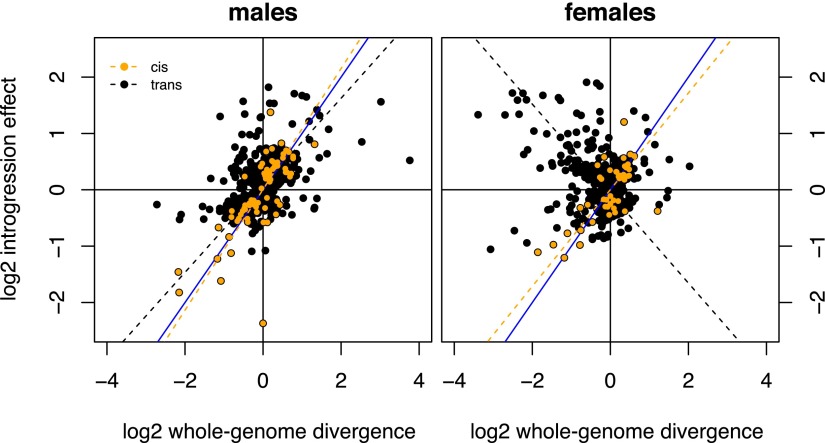

Finally, the relationship between the effects of introgressed factors and whole-genome divergence in expression levels differs significantly between cis- and trans-regulation (Fig. 7), indicating that introgressed cis- and trans-factors are affected differently by mau12 alleles at loci outside the introgressed region. Homozygous introgressed cis-regulatory effects predict well the effects of whole-genome divergence on expression levels at those loci in both sexes (ρmales = 0.75, ρfemales = 0.85, P < 0.0001). In contrast, the effects of introgressed trans-acting factors are significantly poorer predictors of whole-genome divergence in expression levels. In males, the correlation between homozygous effects due to trans-regulatory divergence and interspecific divergence, although positive (ρ = 0.40, P < 0.0001), is significantly weaker (P < 0.0001) than for cis-regulatory divergence. In females, there is a significant negative correlation between trans-regulatory introgression effects and whole-genome divergence (ρ = −0.27, P < 0.0001)—on average, D. mauritiana alleles at loci outside the introgressions reverse the effects of introgressed trans-factors in females.

Figure 7.

Differential evolution of gene expression phenotypes in cis versus in trans. In both sexes, the effects of introgressed cis-regulatory divergence are predictive of whole-genome divergence (males: slope = 1.07, ρ = 0.75; females: slope = 0.86, ρ = 0.85, P < 0.0001 in both sexes). In contrast, the effects of introgressed trans-regulatory factors in males are poorer predictors of whole-genome divergence (slope = 0.77, ρ = 0.40, P < 0.0001), implicating modifier alleles elsewhere in the genome. In females, the effects of introgressed trans-regulatory factors are, on average, reversed by alleles elsewhere in the genome in females (slope = −0.79, ρ = −0.27, P < 0.0001). The blue line has a slope of 1.

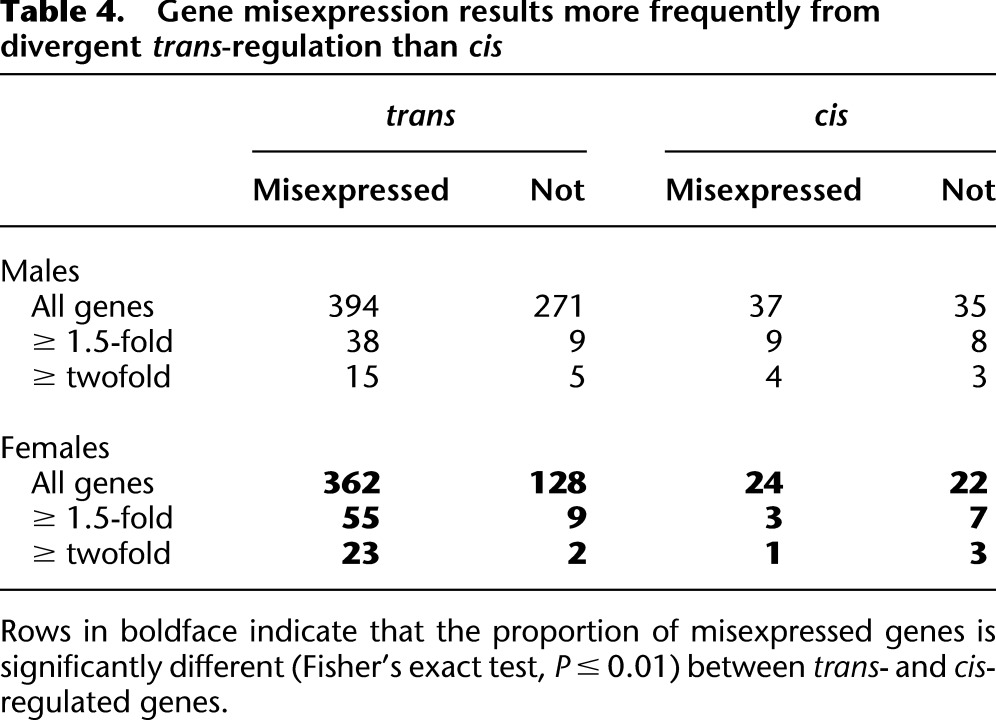

Previous studies have found that in crosses both within (Gibson et al. 2004) and between (Ranz et al. 2004; Landry et al. 2005; McManus et al. 2010) Drosophila species, many genes are expressed in offspring at levels outside the range of both parental genotypes. Such transgressive segregation is consistent with compensatory evolution within species and regulatory incompatibilities among species (Ranz et al. 2003; Ranz et al. 2004; Landry et al. 2005), some of which may contribute to the loss of fitness in hybrids (Michalak and Noor 2003; Michalak and Noor 2004; Good et al. 2010). We refer to those genes expressed in introgression hybrids at levels outside the range of the parental species as “misexpressed.” Substantial majorities of genes in both sexes are misexpressed in introgression hybrids—58% and 72% of divergently regulated genes in males and females, respectively (this difference in the proportion of misexpression between males and females is statistically significant; PFET < 0.0001). We observe an enrichment of misexpressed genes as a result of trans-regulatory divergence, although this pattern is only significant in females (Table 4).

Table 4.

Gene misexpression results more frequently from divergent trans-regulation than cis

Tissue-specific genes diverge more and are more sexually dimorphic in expression than broadly expressed genes

The ubiquity of a gene’s expression is an important determinant of rates of both sequence and expression evolution. Inducible genes in single-celled organisms (Basehoar et al. 2004; Tirosh et al. 2006) and genes expressed in a restricted set of cell types in multicellular organisms (Duret and Mouchiroud 2000; Larracuente et al. 2008) evolve significantly more rapidly than ubiquitously expressed genes. Consistent with these earlier findings, breadth of expression across tissues and organs has a significant impact on the patterns of divergence and sex-biased expression in our data. The magnitude of the effects of introgressed factors on gene expression, whole-genome expression divergence between simB and mau12, the magnitude of allele-specific expression in introgression heterozygotes, and the difference in these effects between males and females are all larger among tissue-specific genes than broadly expressed genes (Supplemental Table 6); these results generally hold for both cis- and trans-regulatory divergence. As whole animals were used for expression analysis, the expression effects among tissue-specific genes are almost certainly underestimated (Chintapalli et al. 2007), suggesting that the effects of tissue breadth are even more pronounced than these tallies suggest.

Coregulated genes with immune function are misexpressed in introgression females

There is a significant enrichment of genes associated with the immune response in D. melanogaster (as annotated on FlyBase) among transcripts divergently regulated in females (PFET < 0.0001), but not in males (PFET = 0.6). In particular, among the 25 divergently regulated genes that are up-regulated at least twofold or more in homozygous introgression females, 10 have annotated immune function, and QTL mapping localizes the causative factor to one of two adjacent markers (Supplemental Table 7). Together, these results are consistent with an introgressed functionally divergent D. mauritiana allele of a trans-regulatory factor that affects the expression of multiple effectors of the humoral immune response distributed throughout the genome.

The expression of these 10 immunity genes is positively correlated between the sexes in introgression genotypes (ρ = 0.78, P = 0.008) (Supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that, in a mostly D. simulans genetic background, the D. mauritiana allele of this trans-acting factor has similar effects in males and females. In contrast, relative expression of these genes is uncorrelated between mau12 males and females (P = 0.32); males show variable expression, and females show ≥ twofold down-regulation and misexpression. These observations are consistent with a model whereby D. mauritiana alleles at one or more loci outside the introgressed region decouple the effects of this trans-regulator in males and females, mainly by reversing its effects in females.

Discussion

We used microarray analysis of introgression hybrids between D. mauritiana and D. simulans to sample the genetic basis for genome-wide differences in gene expression between these two species. Below we describe how the evolutionary histories of these species and our approach circumscribe our study before turning to the evolutionary conclusions that we draw from our genetic analyses.

First, D. simulans and D. mauritiana diverged ∼242,000 yr ago and differ at 1.6% of sites across the euchromatic portion of the genome (Garrigan et al. 2012), and by at least 1000 structural differences totaling 1 Mb of euchromatic DNA (Langley et al. 2012). Both species have large effective population sizes and high levels of nucleotide polymorphism (Kliman and Hey 1993; Nolte et al. 2013). Given the large effective population sizes of both species and the recency of their divergence, some unknown number of the genetic factors that we identify are likely polymorphisms segregating in one or both species, rather than fixed differences.

Second, D. simulans and D. mauritiana are separated by multiple systems of reproductive isolation, including premating (Coyne 1992; Coyne and Charlesworth 1997), postmating–prezygotic (Price et al. 2000), and intrinsic postzygotic isolation (Lachaise et al. 1986). It has been estimated that ∼15 loci across the genome can confer complete male sterility and two or three loci cause lethality when introgressed from D. mauritiana into D. simulans (Tao et al. 2003; Cattani and Presgraves 2009). Multiple mtDNA haplotypes have recently introgressed from D. simulans into D. mauritiana (Ballard 2000; Nunes et al. 2010; Garrigan et al. 2012), and 2%–5% of 5-kb genomic segments have evolutionary histories consistent with recent gene flow between these two species (Garrigan et al. 2012). Thus, there is the opportunity for gene flow between these two species, but significant barriers to gene flow also exist in the form of both a few major and presumably many more minor hybrid incompatibilities (True et al. 1996). Due to the accumulation of intrinsic postzygotic incompatibilities, we expect that many gene expression phenotypes associated with introgressed factors are deleterious; however, we do not know the fitness effects associated with the observed expression phenotypes. Nonetheless, in view of the reduced opportunity for selection to act in hybrids relative to the parental species, we assume that introgression hybrids are more likely to have deleterious patterns of gene expression than either of the pure species genotypes.

Third, we observe that ∼90% of divergently regulated genes change expression as a result of species divergence at trans-factors (Table 1). Most previous studies in Drosophila have inferred that cis-regulatory divergence can account for at least 50% of differences in gene expression both within (Hughes et al. 2006; Genissel et al. 2008; Lemos et al. 2008a) and between species (Wittkopp et al. 2004, 2008; McManus et al. 2010). The large proportion of trans-divergence we detect here can likely be attributed to our use of homozygous introgression hybrids, as opposed to assaying F1 progeny, for two reasons. First, our introgression approach sampled regulatory divergence across 9.3 Mb and estimated the effects of this divergence on genome-wide gene expression. Due to the polygenic nature of gene expression (Brem et al. 2002; Schadt et al. 2003; Brem and Kruglyak 2005; Gibson and Weir 2005), some differences in gene expression between these species result from divergence at multiple trans-acting loci. Because some genes divergently regulated by an introgressed trans-factor are also regulated by divergence at loci not captured by these introgressions, this approach overestimates the proportion of genes genome-wide that are divergently regulated in trans. Second, regulatory alleles that act recessively will be masked in F1 hybrids. Previous studies (Lemos et al. 2008a; McManus et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2011; Gruber et al. 2012) and our results suggest that recessive alleles more frequently underlie trans-regulatory divergence (Table 4); F1 analyses therefore likely underestimate divergent trans-regulation. A recent mutagenesis study in Saccharomyces cereviseae is also broadly consistent with the idea that genome-wide heterozygosity may mask trans-regulatory variation. Gruber et al. (2012) found that >80% of de novo mutations assayed in a common genetic background acted in trans to modulate reporter gene expression, and these trans-mutations were masked in heterozygous diploids.

Finally, we studied a single autosomal region for effects on genome-wide gene expression. It is therefore important to consider which results are likely to generally hold for regulatory divergence between D. simulans and D. mauritiana, and which may be idiosyncratic to the evolutionary history of this particular region of the genome. We assume that the majority of cis-regulatory divergence acts gene specifically, excepting the candidate region highlighted in Figure 5. Patterns associated with divergence in cis therefore result from many independent regulatory substitutions and therefore are likely to generally apply to autosomal, euchromatic cis-regulatory divergence between these species. In both sexes, each of the 10 genetic markers (Fig. 1) showed linkage to multiple trans-regulated expression phenotypes, indicating that, at a minimum, 10 divergent factors are required to account for the trans-regulatory divergence we observe. Patterns that we observe among trans-regulated expression phenotypes linked to all markers are the result of divergence at multiple regulatory factors and are therefore also likely to reveal general features of regulatory divergence between these two species. In contrast, patterns that are driven by expression phenotypes linked to only one marker are more likely to be idiosyncratic consequences of the specific mutations captured by these introgressions. Across both sexes, 67% of genes up-regulated more than 1.5-fold in trans show linkage to the same marker, and many of these genes have annotated immune function, suggesting that the large fraction of up-regulation in these genotypes (Table 2) and the enrichment of strongly up-regulated genes with immune function (Supplemental Table 7) may be due to a single introgressed trans-regulatory factor of large effect. All other patterns we describe are more likely to be general features of regulatory divergence in Drosophila.

Although a bias toward up-regulation in trans has been observed among de novo regulatory mutations in S. cereviseae (Gruber et al. 2012), studies in Drosophila have found a significant excess of genes down-regulated in interspecific F1 hybrids relative to both parent species (Michalak and Noor 2003; Ranz et al. 2004; Moehring et al. 2007; McManus et al. 2010). However, these studies profiled sterile individuals with sterility phenotypes that range from post-meiotic disruption of gametogenesis (Kulathinal and Singh 1998) to largely agametic (Sturtevant 1920), and the large number of underexpressed genes results at least in part from assaying whole animals lacking germline cells, compared with fertile individuals from the parental species (Ranz et al. 2004; McManus et al. 2010). Both sexes of the introgression hybrids used here are fertile, and thus gross differences in tissue composition between genotypes are not expected. As mentioned above, the up-regulation in trans we detect may be attributable to a single large-effect factor; it therefore remains unclear if biases toward up- or down-regulation are, in fact, common features of gene misregulation in Drosophila hybrids.

The evolution of sexually dimorphic gene expression

Assaying gene expression in both males and females allowed us to identify sex-biased and sex-specific effects of regulatory divergence. We detect significantly more divergently regulated genes in males than in females despite the fact that the false discovery rate is slightly higher in females (see Methods). An excess of cis-eQTL in males was also detected in a North Carolina population of D. melanogaster (Massouras et al. 2012). One possible explanation for these observations is that global gene expression in Drosophila males is simply more sensitive than expression in females to genetic variation and divergence. For example, genetic perturbations affecting heterochromatin have more severe effects on genome-wide expression in males than females (Liu et al. 2005; Deng et al. 2009), which may reflect interactions with male-specific factors that affect both euchromatic and heterochromatic gene regulation, such as the Y chromosome (Lemos et al. 2008b), or the somatic dosage compensation complex (Deng et al. 2009). However, we caution that greater statistical power associated with the microarray experiments in males, e.g., due to greater technical variation or sensitivity to random environmental effects in females, could potentially contribute to the excess of divergently regulated genes detected in males.

It has been proposed that the evolution of sexually dimorphic gene expression is driven in part by selection to resolve sexually antagonistic fitness variation (Rice 1984). This model assumes that mutations are generally less sexually dimorphic than required for optimal fitness in both sexes, in contrast to a model in which most mutations have disparate effects in males and females, and subsequent evolution restores fitness to the disfavored sex via reducing sexual dimorphism in expression. Mutation accumulation experiments in animals have measured the effects of de novo mutations on gene expression in one sex only (Denver et al. 2005; Rifkin et al. 2005), so the degree of sexual dimorphism among new mutations affecting gene expression levels is currently unknown. We observe that, among genes regulated by divergent trans-factors, the effects of introgressed alleles on gene expression are more similar between the males and females than the effects of genome-wide divergence between simB and mau12, indicating that D. mauritiana alleles elsewhere in the genome increase sexual dimorphism in expression relative to the introgressed trans-factors. Assuming that reduced dimorphism in some expression phenotypes due to introgressed regulatory factors confers decreased fitness relative to the pure species genotypes, this pattern supports the scenario whereby compensatory evolution increases the sexual dimorphism of individual mutations and suggests the existence of the modifier alleles predicted by Rice’s model (Rice 1984).

The median homozygous effect of introgressed cis-regulatory sequences is 40% more sexually dimorphic than the median effect of introgressed trans-regulatory factors (Fig. 5), and the effects of cis-regulatory divergence in males and females are similar in the simB and mau12 backgrounds (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. 5). This indicates that, while mau12 alleles at loci outside the introgressions modulate the effects of introgressed trans-factors to increase sex differences in expression, such modulation is, on average, less frequent for cis-regulatory divergence. Case studies have repeatedly identified that divergence at cis-regulatory elements is responsible for the evolution of sex-specific patterns of gene expression (Gompel et al. 2005; Jeong et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2008), and a population genomic study found that 75% of cis-eQTL are sex specific within a single D. melanogaster population (Massouras et al. 2012). Together with these studies, our results suggest that disparity in expression between the sexes may be a general feature of cis-regulatory control and that this disparity includes overall expression levels, in addition to the timing and spatial patterns of gene expression through development. If different expression optima in males and females are common, this may be an important pleiotropic constraint that is alleviated by cis-regulatory evolution (Stern 2000).

The enrichment of sexually dimorphic gene expression associated with cis-regulation could conceivably result from either molecular mechanisms of gene regulation or evolutionary processes. In Drosophila, global differences between males and females in the balance of euchromatin and heterochromatin (Deng et al. 2009) and the distribution of covalent histone modifications (Lucchesi et al. 2005) may give males and females distinct chromatin states across the genome, which could enrich sexually dimorphic effects among cis-regulatory mutations. An alternate, but not mutually exclusive, possibility is that cis-regulatory mutations that affect sexually dimorphic expression are more likely to be tightly linked to sexually antagonistic protein-coding mutations located in the same gene, potentially facilitating the spread of both mutations through a population (Rice 1984).

Dominance and the evolution of gene expression

Assaying gene expression in homozygous and heterozygous introgression genotypes allowed us to estimate the dominance of divergent regulatory factors. We observe that, in contrast to the additive effects of introgressed factors, dominance effects are independent between males and females, and are even weakly negatively correlated among cis-regulatory divergence (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, D. mauritiana trans-regulatory alleles are predominantly dominant in males only (Table 3). These observations have important implications for our understanding of sexually antagonistic fitness variation, as the dominance of sexually antagonistic mutations is a critical parameter determining their fate in populations. Sex-specific dominance resulting from X-chromosome hemizygosity in males allows X-linked sexually antagonistic alleles to segregate at higher frequencies than equivalent autosomal alleles that have similar dominance effects between males and females (Rice 1984). However, we observe extensive sex-specific dominance in expression effects associated with introgressed autosomal regulatory factors. If sex-specific dominance is common, then the fate of sexually antagonistic alleles within populations may be largely determined by the particular combination of sex-specific fitness effects and dominance relationships associated with these mutations, and sexually antagonistic fitness variation may not be restricted to the X chromosome (Fry 2010).

The dominance of gene expression changes differs significantly between divergent cis- and trans-regulation. Divergent trans-regulation is enriched for dominant or recessive alleles, while the effects of cis-regulatory divergence are intermediate in heterozygous genotypes (Fig. 6; Table 3). Additivity has been previously documented for cis-regulatory variants (Wray 2007; Lemos et al. 2008a; McManus et al. 2010; Gruber et al. 2012) and is expected in the absence of transvection due to independent transcription of homologous alleles in a diploid heterozygote (Wray 2007). As additive effects expose rare alleles to selection, this may cause fewer advantageous cis-regulatory alleles to be lost to drift, potentially enriching their fixation relative to their mutational origination as compared with trans-acting mutations (Wray 2007). Additionally, additivity may enrich cis-regulatory variants for mutations with heterozygote advantage and influence levels of standing cis-regulatory genetic variation (Sellis et al. 2011).

The contributions of cis- and trans-regulatory divergence to the evolution of gene expression

The average fold-change resulting from cis-regulatory divergence identified here is significantly larger than those resulting from trans-divergence (Supplemental Table 5), consistent with what appears to be a general pattern of larger expression effects associated with cis-regulatory variation (Brem et al. 2002; Schadt et al. 2003; Hughes et al. 2006; Lemos et al. 2008a; McManus et al. 2010; Gruber et al. 2012). The effects of divergent trans-regulatory factors are weakly correlated (in males) or anti-correlated (in females) with overall expression differences between simB and mau12, while the effects of cis-regulatory divergence are positively correlated with interspecific expression differences (Fig. 7), resulting in an excess of gene misexpression due to divergent trans-regulation (Table 4). In our experiments, divergent regulation in both cis and trans results from interspecific interactions between alleles that modulate gene expression (D. simulans trans-factors with D. mauritiana cis-regulatory sequences and D. mauritiana trans-factors with D. simulans cis-regulatory sequences, respectively). However, only divergent trans-regulation is affected by interactions between trans-factors from both species. Interspecific interactions between trans-factors, then, could be responsible for the observed misexpression bias. If true, this suggests that misexpression rarely results from direct interactions between trans-factors and cis-regulatory sequences, but rather as a downstream consequence of interspecific interactions between alleles at two trans-regulatory factors, or between alleles at loci whose effects on gene expression are indirect (Yvert et al. 2003).

Finally, our results have implications for the evolution of gene expression phenotypes and the accumulation of incompatibilities that contribute to or follow reproductive isolation. For gene expression levels that are under stabilizing selection in both species—which is likely the majority (Rifkin et al. 2003; Denver et al. 2005; Lemos et al. 2005; Ronald and Akey 2007)—expression phenotypes that are deleterious in the introgression hybrid relative to both parental species will be enriched among misexpressed genes, where expression in the hybrid is outside the range of the parents. Such expression incompatibilities will therefore be more common among trans-regulatory divergences, and, as described above, these may result mostly from trans–trans interactions. This suggests that evolutionary turnover of cis-regulatory DNA and the proteins that interact with these sequences may contribute less to the evolution of incompatibilities, at least for the expression of euchromatic single-copy genes. Additionally, if a significant fraction of regulatory mutations select for secondary mutations that modify regulatory effects in a sex-specific manner, then sex-specific misexpression may contribute to a loss of fitness in hybrids.

Methods

Drosophila genetics and husbandry

The construction of the introgression genotypes used here was originally described in Tao et al. (2003). Stocks of a D. mauritiana w− strain (mau12) carrying a codominant visible marker (P[w+]) on the third chromosome were crossed to a w− strain of D. simulans, and hybrid females carrying D. mauritiana material marked by P[w+] were backcrossed to D. simulans w− males for four generations. Introgression lines were then crossed to a w− genotype of D. simulans (referred to hereafter as simB) with a recessively marked second chromosome, and third chromosomes carrying introgressed segments were passaged through males to ensure that the X and second chromosomes were derived entirely from simB. To eliminate mutations that may have accumulated in these lines since their construction (e.g., Denver et al. 2005; Rifkin et al. 2005; Landry et al. 2007), the introgressed D. mauritiana segments were re-extracted into the simB background using the crossing scheme shown in Supplemental Figure 6. In the final generation of the re-extraction, single males and females were paired to create sublines of each original introgression genotype. To confirm that the introgressions remained intact following two generations of recombination in females, all sublines were genotyped at markers originally used to identify the limits of the introgressions (Tao et al. 2003); following confirmation, five sublines were selected and pooled to regenerate the introgression lines.

Seven lines carrying introgressed D. mauritiana genomic segments in cytological divisions 66B–71B on chromosome arm 3L were used for the current experiments. Gene expression was assayed in homozygous introgression genotypes, heterozygous introgression genotypes (introgression/simB), and the parental simB and mau12 strains, for a total of 16 genotypes.

All flies used for RNA extraction were reared on standard cornmeal molasses media in glass vials at 25°C on a 12:12 light:dark cycle. Culture density was controlled by combining 15 males with 15 females per vial for homozygous introgression genotypes, and 10 males with 10 females for the simB, mau12, and heterozygous introgression genotypes. Flies for RNA extraction were reared in three independent cohorts. Adults were collected as virgins, and the sexes were aged separately for 1–2 d before flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at −80°C. All flies were frozen at the same time of day to control for circadian effects on gene expression. Heterozygous introgression genotypes were generated from both reciprocal crosses, i.e., virgin simB females were crossed to introgression line males, virgin introgression line females were crossed to simB males, and equal amounts of RNA extracted from the offspring of reciprocal crosses were pooled for microarray hybridization. This approach averages over any potential parent-of-origin effects on expression, and thus such effects can neither be detected nor confound our results; in any case, there is little evidence for imprinting or parent-of-origin effects on gene expression in adult Drosophila (Coolon et al. 2012).

Microarray and pyrosequencing methods

Microarray construction, RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and hybridization were performed following standard protocols. Two-color competitive hybridizations followed a modified loop design (Supplemental Fig. 7) that minimizes the distance between any two genotypes (Townsend 2003). Allele-specific expression was assayed by pyrosequencing at 90 candidate genes identified from the microarrays as potentially harboring cis-regulatory variants (Supplemental Fig. 8; Supplemental Table 1). Detailed microarray and pyrosequencing methods are available as Supplemental Material.

Statistical analyses

Microarray log2 expression ratios were analyzed with an empirical Bayes linear model (Smyth 2004), and relative expression levels (log2 fold-change) were estimated for each homozygous and heterozygous introgression genotype, simB, and mau12, setting expression levels in simB equal to 0. Estimates of gene expression levels obtained from the linear model were then used for QTL analysis. Expression estimates from mau12 were excluded from the QTL analysis, as this strain differs in genetic background from the simB and introgression lines. Expression levels in mau12 were used in post hoc comparisons to infer patterns of gene expression evolution and misexpression.

Genotype data for QTL mapping were collected at markers across the introgressed region (Fig. 1). Marker regression (Haley and Knott 1992) was used to detect associations between marker genotype (mau/mau, mau/sim, or sim/sim) and gene expression level (log2 fold-change relative to simB). Significance was determined by a χ2 test, and the effects of introgression genotypes on expression phenotypes are reported as the additive (a) and dominance (d) parameters estimated from the Haley-Knott regression. In this model, expression in homozygous introgression genotypes is estimated by 2a and expression in heterozygous introgression genotypes by a + d. QTL analyses were done using R/qtl v1.23 (Broman et al. 2003).

The P-value cutoff for assigning a statistically significant association between expression phenotypes and genetic markers was obtained by setting the false discovery rate (FDR) (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) to 0.02 in males, which corresponds to a nominal χ2 P-value of 0.00021. This P-value cutoff was then used for both the male and female experiments, resulting in an FDR of 0.03 in females. This FDR was calculated using all linkage tests at all markers, but we considered only the marker with the best fit for each gene expression phenotype. This approach is very conservative with respect to false positives, as shown in Q–Q plots of the QTL linkage P-values (Supplemental Fig. 9). A common P-value cutoff and slightly different FDR rates across the sexes were deemed preferable to controlling the FDR to a common value in both males and females, as an FDR of 0.02 in females corresponds to a nominal P-value of 0.000065, which reduces the number of observed significant associations in females by half. Our decision to set a common P-value cutoff is therefore conservative with regard to the excess in the number of significant associations detected in males.

Normalized log2-transformed relative expression measures from pyrosequencing were analyzed in two steps. First, a mixed linear model including main effects of sex, strain, reciprocal cross, and all two-way interactions were fit for all genes separately, excepting four genes assayed using only one genotype, for which the model included sex, reciprocal cross, and their interaction. The results of these models were examined, and effects of strain and cross and their interactions were dropped if they were not significant. Based on this approach, one of three statistical models was used for each gene (see Supplemental Table 8):

(1) log2 normalized ratio of allelic expression ∼ sex + strain + ɛ (four genes)

(2) log2 normalized ratio of allelic expression ∼ sex + cross + sex * cross + ɛ (five genes)

(3) log2 normalized ratio of allelic expression ∼ sex + ɛ (81 genes)

All models used type III sums of squares and were run using the GLM procedure in SAS statistical software (version 10).

FlyAtlas analyses

Gene expression estimates from 20 tissues dissected from larval and adult D. melanogaster were compiled from FlyAtlas (Chintapalli et al. 2007). Affymetrix microarray probe sets with multiple matches to the genome were excluded from the analysis, and among genes with multiple probe sets, the probe set with the highest mean signal intensity across samples was selected. Signal intensities at probe sets with absent calls were set to 1, and all intensity values were log2-transformed. Mean expression values were then calculated from four replicate arrays. Tissue specificity was calculated as the τ statistic (Yanai et al. 2005).

All statistical analyses except for the pyrosequencing models were done in R (v2.14.1) (R Development Core Team 2011). Microarray analyses used the limma package (v3.10.3); standardized major axis regression was used for bivariate regression analysis with the smatr package (v3.2.4).

Data access

Microarray data have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE44329. Pyrosequencing data are included in Supplemental Table 8.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Rand for his generous support, Yun Tao for providing the introgression genotypes, and Daven Presgraves and Kristi Montooth for comments that improved the manuscript. This work was supported by funds from the NSF to C.D.M. (DEB-0839348) and P.J.W. (MCB-1021398) and funds from the NIH to J.D.C. (1F32-GM089009-01A1) and D.L.H. (GM065169).

Author contributions: C.D.M., J.D.C., and P.J.W. conceived and designed the experiments; C.D.M. and J.D.C. performed the experiments; C.D.M. and J.D.C. analyzed the data; C.D.M., D.L.H., and P.J.W. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; and C.D.M. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.156414.113.

Freely available online through the Genome Research Open Access option.

References

- Ballard JWO 2000. Comparative genomics of mitochondrial DNA in members of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. J Mol Evol 51: 48–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basehoar AD, Zanton SJ, Pugh BF 2004. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell 116: 699–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 57: 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- Brawand D, Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Julien P, Csardi G, Harrigan P, Weier M, Liechti A, Aximu-Petri A, Kircher M, et al. 2011. The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature 478: 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem RB, Kruglyak L 2005. The landscape of genetic complexity across 5,700 gene expression traits in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 1572–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem RB, Yvert G, Clinton R, Kruglyak L 2002. Genetic dissection of transcriptional regulation in budding yeast. Science 296: 752–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten RJ, Davidson EH 1969. Gene regulation for higher cells—a theory. Science 165: 349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA 2003. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19: 889–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SB 2005. Evolution at two levels: On genes and form. PLoS Biol 3: 1159–1166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattani MV, Presgraves DC 2009. Genetics and lineage-specific evolution of a lethal hybrid incompatibility between Drosophila mauritiana and its sibling species. Genetics 181: 1545–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA 2007. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet 39: 715–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connallon T, Knowles LL 2005. Intergenomic conflict revealed by patterns of sex-biased gene expression. Trends Genet 21: 495–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolon JD, Stevenson KR, McManus CJ, Graveley BR, Wittkopp PJ 2012. Genomic imprinting absent in Drosophila melanogaster adult females. Cell Rep 2: 69–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA 1992. Genetics of sexual isolation in females of the Drosophila simulans species complex. Genet Res 60: 25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Charlesworth B 1997. Genetics of a pheromonal difference affecting sexual isolation between Drosophila mauritiana and D-sechellia. Genetics 145: 1015–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Koya SK, Kong Y, Meller VH 2009. Coordinated regulation of heterochromatic genes in Drosophila melanogaster males. Genetics 182: 481–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver DR, Morris K, Streelman JT, Kim SK, Lynch M, Thomas WK 2005. The transcriptional consequences of mutation and natural selection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Genet 37: 544–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L, Mouchiroud D 2000. Determinants of substitution rates in mammalian genes: Expression pattern affects selection intensity but not mutation rate. Mol Biol Evol 17: 68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson JJ, Hsieh LC, Sung HM, Wang TY, Huang CJ, Lu HH, Lu MY, Wu SH, Li WH 2010. Natural selection on cis and trans regulation in yeasts. Genome Res 20: 826–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay JC, Wittkopp PJ 2008. Evaluating the role of natural selection in the evolution of gene regulation. Heredity (Edinb) 100: 191–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry JD 2010. The genomic location of sexually antagonistic variation: Some cautionary comments. Evolution 64: 1510–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D, Kingan SB, Geneva AJ, Andolfatto P, Clark AG, Thornton KR, Presgraves DC 2012. Genome sequencing reveals complex speciation in the Drosophila simulans clade. Genome Res 22: 1499–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbart ME, Kuroda MI 2009. Drosophila dosage compensation: A complex voyage to the X chromosome. Development 136: 1399–1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genissel A, McIntyre LM, Wayne ML, Nuzhdin SV 2008. Cis and trans regulatory effects contribute to natural variation in transcriptome of Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol 25: 101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Weir B 2005. The quantitative genetics of transcription. Trends Genet 21: 616–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Riley-Berger R, Harshman L, Kopp A, Vacha S, Nuzhdin S, Wayne M 2004. Extensive sex-specific nonadditivity of gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167: 1791–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnad F, Parsch J 2006. Sebida: A database for the functional and evolutionary analysis of genes with sex-biased expression. Bioinformatics 22: 2577–2579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gompel N, Prud’homme B, Wittkopp PJ, Kassner VA, Carroll SB 2005. Chance caught on the wing: cis-regulatory evolution and the origin of pigment patterns in Drosophila. Nature 433: 481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good JM, Giger T, Dean MD, Nachman MW 2010. Widespread over-expression of the X chromosome in sterile F1 hybrid mice. PLoS Genet 6: e1001148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graze RM, McIntyre LM, Main BJ, Wayne ML, Nuzhdin SV 2009. Regulatory divergence in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans, a genomewide analysis of allele-specific expression. Genetics 183: 547–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber JD, Vogel K, Kalay G, Wittkopp PJ 2012. Contrasting properties of gene-specific regulatory, coding, and copy number mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Frequency, effects, and dominance. PLoS Genet 8: e1002497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley CS, Knott SA 1992. A simple regression method for mapping quantitative trait loci in line crosses using flanking markers. Heredity (Edinb) 69: 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes KA, Ayroles JF, Reedy MM, Drnevich JM, Rowe KC, Ruedi EA, Caceres CE, Paige KN 2006. Segregating variation in the transcriptome: Cis regulation and additivity of effects. Genetics 173: 1347–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti P, Morrow EH 2010. The sexually antagonistic genes of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol 8: e1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S, Rokas A, Carroll SB 2006. Regulation of body pigmentation by the Abdominal-B Hox protein and its gain and loss in Drosophila evolution. Cell 125: 1387–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MC, Wilson AC 1975. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188: 107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliman RM, Hey J 1993. DNA sequence variation at the period locus within and among species of the Drosophila melanogaster complex. Genetics 133: 375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal R, Singh RS 1998. Cytological characterization of premeiotic versus postmeiotic defects producing hybrid male sterility among sibling species of the Drosophila melanogaster complex. Evolution 52: 1067–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise D, David JR, Lemeunier F, Tsacas L, Ashburner M 1986. The reproductive relationships of Drosophila sechellia with D. mauritiana, D. simulans, and D. melanogaster from the Afrotropical region. Evolution 1986: 262–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry CR, Wittkopp PJ, Taubes CH, Ranz JM, Clark AG, Hartl DL 2005. Compensatory cis-trans evolution and the dysregulation of gene expression in interspecific hybrids of Drosophila. Genetics 171: 1813–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry CR, Lemos B, Rifkin SA, Dickinson WJ, Hartl DL 2007. Genetic properties influencing the evolvability of gene expression. Science 317: 118–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley CH, Stevens K, Cardeno C, Lee YC, Schrider DR, Pool JE, Langley SA, Suarez C, Corbett-Detig RB, Kolaczkowski B, et al. 2012. Genomic variation in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 192: 533–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larracuente AM, Sackton TB, Greenberg AJ, Wong A, Singh ND, Sturgill D, Zhang Y, Oliver B, Clark AG 2008. Evolution of protein-coding genes in Drosophila. Trends Genet 24: 114–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson Handley LJ, Perrin N 2007. Advances in our understanding of mammalian sex-biased dispersal. Mol Ecol 16: 1559–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos B, Meiklejohn CD, Caceres M, Hartl DL 2005. Rates of divergence in gene expression profiles of primates, mice, and flies: Stabilizing selection and variability among functional categories. Evolution 59: 126–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos B, Araripe LO, Fontanillas P, Hartl DL 2008a. Dominance and the evolutionary accumulation of cis- and trans-effects on gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 14471–14476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos B, Araripe LO, Hartl DL 2008b. Polymorphic Y chromosomes harbor cryptic variation with manifold functional consequences. Science 319: 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Burmeister M 2005. Genetical genomics: Combining genetics with gene expression analysis. Hum Mol Genet (Suppl 2) 14: R163–R169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LP, Ni JQ, Shi YD, Oakeley EJ, Sun FL 2005. Sex-specific role of Drosophila melanogaster HP1 in regulating chromatin structure and gene transcription. Nat Genet 37: 1361–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XM, Shapiro JA, Ting CT, Li Y, Li CY, Xu J, Huang HW, Cheng YJ, Greenberg AJ, Li SH, et al. 2010. Genome-wide misexpression of X-linked versus autosomal genes associated with hybrid male sterility. Genome Res 20: 1097–1102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi JC, Kelly WG, Panning B 2005. Chromatin remodeling in dosage compensation. Annu Rev Genet 39: 615–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massouras A, Waszak SM, Albarca-Aguilera M, Hens K, Holcombe W, Ayroles JF, Dermitzakis ET, Stone EA, Jensen JD, Mackay TF, et al. 2012. Genomic variation and its impact on gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet 8: e1003055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus CJ, Coolon JD, Duff MO, Eipper-Mains J, Graveley BR, Wittkopp PJ 2010. Regulatory divergence in Drosophila revealed by mRNA-seq. Genome Res 20: 816–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiklejohn CD, Parsch J, Ranz JM, Hartl DL 2003. Rapid evolution of male-biased gene expression in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 9894–9899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak P, Noor MAF 2003. Genome-wide patterns of expression in Drosophila pure species and hybrid males. Mol Biol Evol 20: 1070–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak P, Noor MAF 2004. Association of misexpression with sterility in hybrids of Drosophila simulans and D. mauritiana. J Mol Evol 59: 277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehring AJ, Teeter KC, Noor MAF 2007. Genome-wide patterns of expression in Drosophila pure species and hybrid males. II. Examination of multiple-species hybridizations, platforms, and life cycle stages. Mol Biol Evol 24: 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte V, Pandey RV, Kofler R, Schlotterer C 2013. Genome-wide patterns of natural variation reveal strong selective sweeps and ongoing genomic conflict in Drosophila mauritiana. Genome Res 23: 99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes MD, Wengel PO, Kreissl M, Schlotterer C 2010. Multiple hybridization events between Drosophila simulans and Drosophila mauritiana are supported by mtDNA introgression. Mol Ecol 19: 4695–4707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CS, Kim CH, Posluszny J, Coyne JA 2000. Mechanisms of conspecific sperm precedence in Drosophila. Evolution 54: 2028–2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. 2011. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Ranz JM, Castillo-Davis CI, Meiklejohn CD, Hartl DL 2003. Sex-dependent gene expression and evolution of the Drosophila transcriptome. Science 300: 1745–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranz JM, Namgyal K, Gibson G, Hartl DL 2004. Anomalies in the expression profile of interspecific hybrids of Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Genome Res 14: 373–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W 1984. Sex chromosomes and the evolution of sexual dimorphism. Evolution 38: 735–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin SA, Kim J, White KP 2003. Evolution of gene expression in the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. Nat Genet 33: 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin SA, Houle D, Kim J, White KP 2005. A mutation accumulation assay reveals a broad capacity for rapid evolution of gene expression. Nature 438: 220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero IG, Ruvinsky I, Gilad Y 2012. Comparative studies of gene expression and the evolution of gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet 13: 505–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronald J, Akey JM 2007. The evolution of gene expression QTL in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 2: e678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadt EE, Monks SA, Drake TA, Lusis AJ, Che N, Colinayo V, Ruff TG, Milligan SB, Lamb JR, Cavet G, et al. 2003. Genetics of gene expression surveyed in maize, mouse and man. Nature 422: 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellis D, Callahan BJ, Petrov DA, Messer PW 2011. Heterozygote advantage as a natural consequence of adaptation in diploids. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 20666–20671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth GK 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 3: Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DL 2000. Evolutionary developmental biology and the problem of variation. Evolution 54: 1079–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant AH 1920. Genetic studies on Drosophila simulans. I. Introduction. Hybrids with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 5: 488–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Chen S, Hartl DL, Laurie CC 2003. Genetic dissection of hybrid incompatibilities between Drosophila simulans and D. mauritiana. I. Differential accumulation of hybrid male sterility effects on the X and autosomes. Genetics 164: 1383–1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I, Weinberger A, Carmi M, Barkai N 2006. A genetic signature of interspecies variations in gene expression. Nat Genet 38: 830–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JP 2003. Multifactorial experimental design and the transitivity of ratios with spotted DNA microarrays. BMC Genomics 4: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True JR, Weir BS, Laurie CC 1996. A genome-wide survey of hybrid incompatibility factors by the introgression of marked segments of Drosophila mauritiana chromosomes into Drosophila simulans. Genetics 142: 819–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TM, Selegue JE, Werner T, Gompel N, Kopp A, Carroll SB 2008. The regulation and evolution of a genetic switch controlling sexually dimorphic traits in Drosophila. Cell 134: 610–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp PJ, Haerum BK, Clark AG 2004. Evolutionary changes in cis and trans gene regulation. Nature 430: 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopp PJ, Haerum BK, Clark AG 2008. Regulatory changes underlying expression differences within and between Drosophila species. Nat Genet 40: 346–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray GA 2007. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nat Rev Genet 8: 206–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanai I, Benjamin H, Shmoish M, Chalifa-Caspi V, Shklar M, Ophir R, Bar-Even A, Horn-Saban S, Safran M, Domany E, et al. 2005. Genome-wide midrange transcription profiles reveal expression level relationships in human tissue specification. Bioinformatics 21: 650–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yvert G, Brem RB, Whittle J, Akey JM, Foss E, Smith EN, Mackelprang R, Kruglyak L 2003. Trans-acting regulatory variation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the role of transcription factors. Nat Genet 35: 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sturgill D, Parisi M, Kumar S, Oliver B 2007. Constraint and turnover in sex-biased gene expression in the genus Drosophila. Nature 450: 233–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cal AJ, Borevitz JO 2011. Genetic architecture of regulatory variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res 21: 725–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]