Abstract

Background:

Diagnostic study of vector ticks for different pathogens transmitted specifically have been done by Iranian old scientists working on the basis of biological transmission of pathogens. In this study we decided to confirm natural infection of different collected ticks from three different provinces of Iran.

Methods:

Ticks were collected from livestock (sheep, goats and cattle) during favorable seasons (April to September 2007 and 2008). Slide preparations were stained by Giemsa and Feulgen and were studied searching for any trace of infection. Positive DNA from infected blood or tissue samples was provided and was used as positive control. First, PCR optimization for positive DNA was done, and then tick samples were subjected to specific PCR.

Results:

Eleven pairs of primers were designed for detection of Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma spp. Totally 21 tick samples were detected to be infected with protozoa. Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum and Rhipicephalus turanicus from Fars Province were infected with T. lestoquardi at two different places. Hyalomma detritum was infected with T. lestoquardi in Lorestan Province and Rh. turanicus was infected to Ba. ovis from Fars Province.

Conclusion:

Totally 21 tick samples were detected to be infected with protozoa. Every sample is regarded with host-environment related factors. Since there are complex relations of vectors and their relevant protozoa, different procedures are presented for future studies.

Keywords: Tick, Vector, Ixodidae, Molecular Detection

Introduction

Vector capacity for ticks (Acari: Ixodida, Ixodidae and Argasidae) transmitting different protozoan pathogens is very specific and has got the attention of old scientists. The first detected vector in the world was Boophilus microplus, when Smith, and Kilborne discovered the etiology of cattle fever, Babesia bigemina, and that it was transmitted by tick vectors, in 1893. Their important work helped set the stage for the discovery of the mosquito vector transmission of yellow fever by Walter Reed and colleagues (Kaplan et al. 2009).

Old Iranian scientists were working on tick and tick borne diseases also tried to confirm vector ticks using tick rearing on experimentally infected host then inducing the infection to the prone host. Review of annual reports of Razi Institute revealed that from 1961 to 1966, Mazlum has recorded 21 species of Ixodidae family collected from different livestock. He denoted Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum as a vector of bovine theileriosis on the basis of non-Iranian scientists studying their home-land vectors. Mazlum also denoted cleverly that on the basis of studies in countries other than Iran, Rhipicephalus bursa is a vector of Theileria hirci (= T. lestoquardi) but, regarding the absence of this species in Sistan and Khouzestan Provinces on that time and regarding the presence of theileriosis due to Th. hirci in sheep in those areas, so another vector should be presented. Mazlum also could transmit Th. annulata by injection of grinded adult infected ticks (Hy. dromedarii) to the host. There is not any documented or recorded background study confirming infected ticks by salivary gland staining methods.

Liebisch et al. (1978) could confirm Hy. anatolicum anatolicum as a vector of Th. annulata by collecting infective ticks and transmitting ticks on a suitable host for blood feeding.

Walker and Mckellar (1983) could successfully transmit the infectivity from nymphal stage to adult stage of Hy. anatolicum anatolicum. All infected adult ticks were mixed and grinded. Slide preparations of the mixture could reveal sporozoite of Th. auunlata after staining by Giemsa.

Tick and tick borne protozoa have been reviewed in a very inclusive article regarding molecular studies on ticks and the protozoan pathogens they carry. There it implies that a specific vector tick may transmit a specific protozoan or some vectors may transmit different pathogens. When rate of infection in the vector ticks is very low, molecular methods and amplification of a target gene can help for confirming a specific pathogen (Sparagano et al. 1999).

Figueroa et al. (1992, 1993) could confirm DNA of Ba. bigemina in collected hemolymphs of female Bo. microplus ticks. Alvarez et al. (1996) confirmed infection rates of up to 50% Ba. bovis infection in extracted DNA from female Bo. microplus blood fed on experimentally infected cattle to Ba. bovis.

Dekok et al. (1993) could confirm an 18S gene sequence of Th. annulata in extracted DNA from Hy. dromedarii and Hy. marginatum mar. using primers designed by Allsopp (1993) for Theileria spp.

Kirvar et al. (1998), could amplify a specific 785 bp segment for Th. lestoquardi after PCR amplification of extracted DNA from Hy. anatolicum anatolicum. There was no cross reaction of infected Hy. anatolicum anatolicum to Th. annulata or specific DNA for cattle.

Habibi et al. (2004) in an experimental molecular study could confirm Ba. ovis infection in collected blood samples from sheep by PCR method. Primers were designed regarding 18S ribosomal RNA gene and ATP binding protein gene.

The purpose of this study was to detect the potential role of ixodidae spp. and natural infection of collected ticks from livestock in three different enzootic geographical regions of Iran. Two different methods (staining of salivary glands and molecular method) were involved and type of infection was detected and presented.

Materials and Methods

Three geographical regions were selected according to different climatic information. Eastern Azerbaijan located in North-Western Iran, Fars Province, Central-Southern Iran and Lorestan Province, Western Iran. Tick infested herds were selected, and ticks were collected from the surface of infested host during favorable seasons (April 2007 to September 2008) (Table 1). The infestation rate was regarded and whole ticks were collected when there were less than 10 ticks over the host and in more infested host as much as 10 ticks were collected. Ticks were put in a clean glass tube capped tightly with cotton and labeled for each infested host, and then samples were transferred in humid chamber to the laboratory. Ticks were identified using different characteristic identification keys (Delpy 1946, Pomerantzev 1950, Delpy 1954, Hoogstraal 1956, Hashemi-Fesharki et al. 2002, Estrada-Pena 2004). Then they were incubated in humid chamber at 28 °C and 85% relative humidity.

Table 1.

Detected ticks and type of protozoan infection by molecular method

| Group | Number of specimens | Protozoan type | Confirmed case of infection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 8 out of 14 | T. lestoquardi | 4-Hyalomma anatolicum ana. F |

| 9-Hyalomma anatolicum ana. F | |||

| 7 | Lorestan-Aligoudarz-Ab-Barik (30/1/87) (18th April 2008) | T. lestoquardi | 1- H. detritum F |

| 5 | Fars-ghir va karzin-Baghe No Karzin (14/6/86) (4th Sep. 2007) (14) | T. lestoquardi | 12- Rhipicephalus turanicus F |

| 13- Rhipicephalus t. N | |||

| 14- Hyalomma anatolicum ana. F | |||

| 1 | Fars-arjan-benroud-Sheepandgoats date: 2/3/86 (22th May 2007) −560mm | Babesia ovis | 4- Rhipicephalus turanicus F, M |

| 5- Rhipicephalus turanicus M | |||

| 7- Rhipicephalus turanicus M | |||

| 8- Rhipicephalus turanicus M | |||

| 10- Rhipicephalus turanicus M | |||

| 13- Rhipicephalus turanicus M | |||

| 14- Rhipicephalus turanicus F, M | |||

| 15- Rhipicephalus turanicus F | |||

| 4 | Fars-ghir va karzin- ashayere dashte bilaki (collection date (14/6/86) (4th Sep. 2007) temp.40°C 250mm (Sheepand goats) (19) | Babesia ovis | 5- Hyalomma anatolicum ana. M |

| 16-Hyalomma anatolicum ana. F | |||

| 18-Hyalomma marginatum M | |||

| 19-Hyalomma sp. F | |||

| 20-Hyalomma anatolicum ana. M |

Confirmation of protozoan infection in ticks

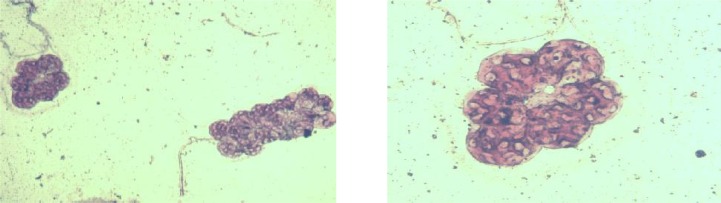

1-Staining method- Salivary glands were pulled out of the body of live ticks and a wet mount has been prepared for each sample, staining was done by Giemsa (Giemsa solution from Merck Company) and Feulgen staining method (using basic Fuchsin according to a Laboratory Manual from Cellular Biology Section at Shiraz University) (Fig. 1 and 2). Comparison of slide preparation with normal salivary gland tissue can reveal the infection caused by some of protozoan agents.

2- Molecular study- DNA extraction was done for suspected ticks, quantity and quality control was done. Each DNA was subjected to a specific primer for ticks (ITS2) (Abdigoudarzi et al. 2011) confirming the specificity. Then confirmed DNA samples were subjected to specific designed primers for Theileria, Babesia and Anaplasma.

Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

Wet mount preparation of Salivary glands of suspected ticks, staining was done by Giemsa and Feulgen, clusters are acini of salivary gland.

Primer design

Ten pairs of primers for detection of five protozoa, including Th. annulata, Ba. bovis, Ba. ovis, Babesia sp. and Anaplasma marginal were designed. The primers were designed according to information at Table 1 and ordering from Sinagen Company. An additional pair of primers specific for amplifying a 785bp segment of gene for a main surface antigen of merozooite, Tams1 (30kda) for Th. annulata (Kirvar et al. 2000) was ordered and have been used in this study too. Tams1 F: (5′-ATG-CTG-CAA-ATG-AGG-AT-3′) and Tspms1 R: (5′-GGA-CTG-ATG-AGA-AGA-CGA-TGA-G-3′).

PCR Protocol

For Tams1 (Th. annulata) denaturation, 94 °C for 3 min, then 40 cycles of (94 °C= 1 min, 60 °C =1 min, 72 °C= 1 min) and final extension 72 °C for 10 minutes. The PCR products run on 1% agarose gel and electrophoresis was done.

PCR protocol for Slag1 (Th. lestoquardi) denaturation, 94 °C for 2 min, then loop1 (11 cycles) (94 °C= 20 sec, 57.5 °C= 45 sec, 72 °C= 30 sec) loop2 (12 cycles) (94 °C=15 sec, 57.5 °C= 30sec, 72 °C= 30 sec) loop3 (17 cycles) (94 °C= 10 sec, 57.5 °C= 15 sec, 72 °C= 30 sec) and final extension 72 °C for 5 minutes.

Results

Totally extracted DNA were divided to 13 groups (171 samples) related to 171 individuals of tick. These are 10% of total samples, 1710 tick samples were collected. Experiments are summarized in five stages as follows.

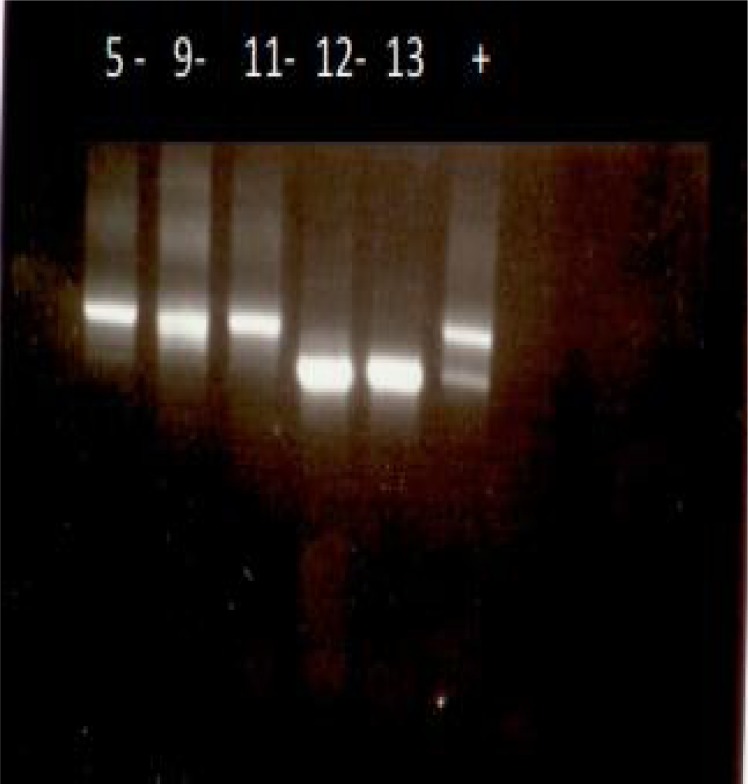

Stage 1–100 DNA samples were subjected to a specific primer for tick identification (ITS2) and 70% were confirmed (Fig. 3). This stage confirms the quantity and quality of extracted DNA from ticks and also the specificity of DNA from ticks (Abdigoudarzi et al. 2011).

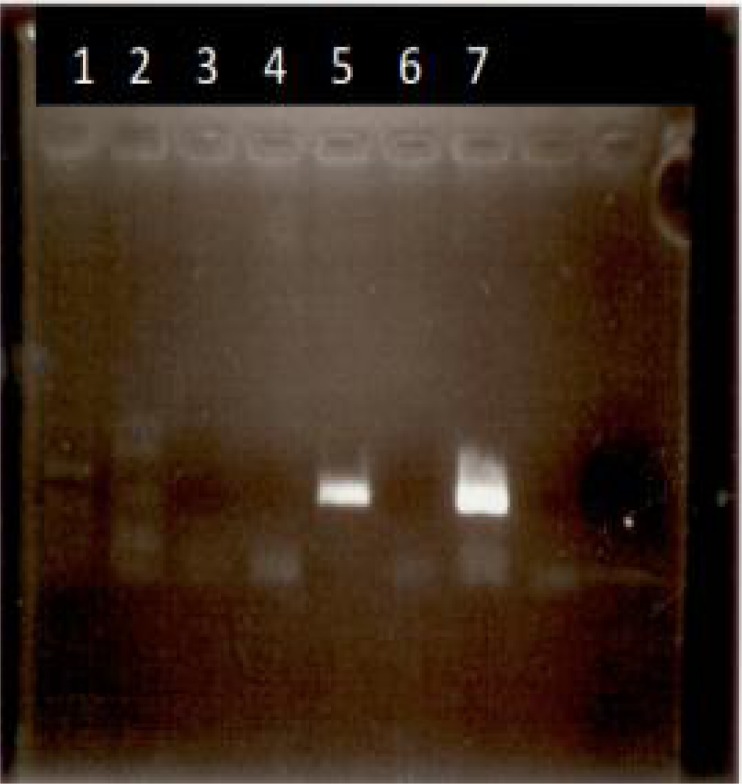

Stage 2- Positive control- for the detection of Ba. ovis and Th. lestoquardi was prepared using positive DNA from Infected blood from infected animals (Fig. 4).

Stage 3- Extracted DNA from Ticks (Groups no. 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11) (86 DNA samples from 86 individuals of ticks) were subjected to a specific primer for Th. annulata (Tams1-F, Tspms1-R). Each group was subjected to PCR when a positive control was included. There was no positive band after gel electrophoresis for tick samples. There was a positive band (≈ 800bp) just for positive control.

Stage 4–33 DNA samples extracted from collected ticks of Shiraz (groups 4 and 5) subjected to a pair of specific primers (Tams1, Tams4) and followed by (Tams3, Tams2) (nested PCR) one sample was detected infected to Th. annulata (Fig. 5) DNA ladder marker is 100bp and size of the amplified segment is 500bp (Fig. 5).

Stage 5- Eight out of 14 samples (group 5) were subjected to specific primers for Th. lestoquardi and protocols of Slag1, two samples were positive for infection. Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products related to DNA group no. 4 (19 specimens) and specific primers for Ba. ovis (Bab3, 4). No. 5 (500 bp), 16, 18, 19 and 20 regarded positive and related individual ticks were recorded infected to Ba. ovis (Fig. 6).

Stage 6- Two type of staining methods were applied on salivary glands of suspected ticks. Regarding the specific biology of salivary glands in blood fed ticks and protozoan life cycle there was no confirmed particles in salivary glands that could be regarded as evidence for the presence of infection. Here in this stage scientific problem are regarded and will be discussed in the following.

Fig. 3.

Sample photo of Agarose gel electrophoresis of pcr products related to extracted DNA from ticks (14 specimens) (Fars Province) and specific primer for ITS2. (No. 5, 9, 11, 12, 13) are very specific good amplified bands confirming the quality and quantity of DNA

Fig. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of pcr products related to DNA positive for T. lestoquardi (line 5) and Babesia ovis (line 7) and specific primers for Slag and Babesia ovis. These (pcr products) (from known positive DNA) have been used as positive control

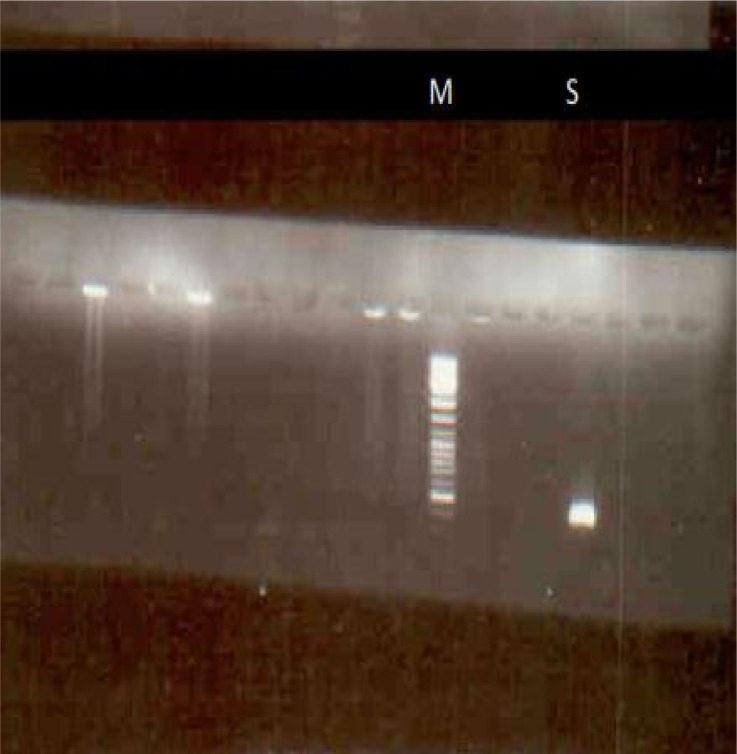

Fig. 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of a 500 bp positive band (S) from a suspected tick (group 5 of Shiraz), Primers are (Tams1, Tams4) followed by (Tams3, Tams2) (a nested pcr was applied) and the infection of tick with T. annulata was confirmed. (Marker is 100 ladder marker) (S= sample)

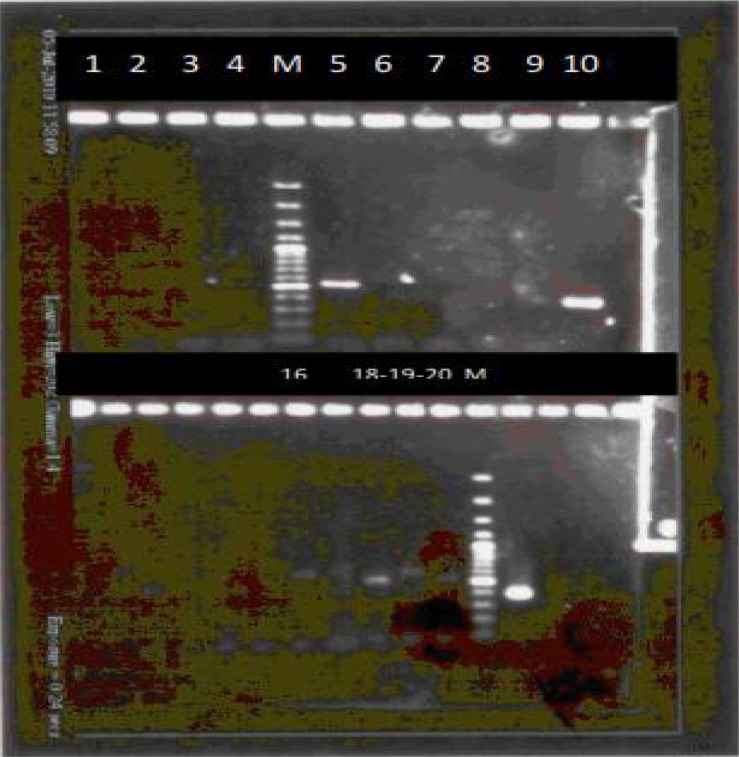

Fig. 6.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of pcr products related to DNA group no. 4 (19 specimens) and specific primers for Babesia ovis (Bab3, 4). No. 5 (500 bp), 16, 18, 19 and 20 regarded positive and related individual ticks were recorded infected to Babesia ovis. (M= 100bp Marker)

Discussion

Regarding sheep and goats, theileriosis due to Th. hirci and babesiosis due to Ba. ovis and Ba. motasi are the most pathogenic protozoa. Ba. crassa, Anaplasma ovis and Eperythrozoon ovis are usually non-pathogenic and do not cause any apparent problem (Hashemi-Fesharki 1997).

In a study in China, the importance of ticks and tick-borne diseases of small ruminants was discussed. Of the 109 species of ticks identified to date of study in China, 45 species infest small ruminants. Five species have been proved to be involved, or possibly involved, in the transmission of tick-borne diseases. Anaplasma ovis, Ba. motasi, Ba. ovis and two unidentified species of Theileria, have been recorded in small ruminants in China (Yin and Luo 2007).

In a study by Shayan et al. (2007), using PCR, DNA was isolated from 269 salivary glands of Rhipicephalus spp. (108 R. bursa, 87 Rh. turanicus, 74 Rh. sanguineus) collected from sheep with suspected to babesiosis. Nested PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism was performed. As positive control for the DNA extraction procedure, the DNA was analyzed with the common primers designed from the 18S rRNA of the Ticks. Ba. ovis was detected in salivary gland of 18.5% R. bursa, 9.1% Rh. turanicus, and 8.1% Rh. sanguineus, respectively (Shayan et al. 2007). In the present study the size of the amplified band for Ba. ovis in Rh. turanicus was 400 bp and it is compatible to anticipated 391 bp from Table 1. It is also similar to the size of amplified band (389 bp) for Ba. ovis in Rh. turanicus in study of the same gene by Shayan et al. 2007. There is no information about the geographical region of study by Shayan et al. 2007, but in our study Ba. ovis infection in Rh. turanicus collected from two different places (Fars- Arjan- Benroud- Sheep and goats) from Fars Province in Iran (Table 1) have been confirmed. In addition, Ba. ovis infection has been confirmed in Hy. anatolicum anatolicum and Hy. marginatum too (Fars-Ghir and Karzin 2007) (Table 1). There is no documented information of these Hyalomma spp. infections to Babesia up to now.

In a similar study in Iran, about 323 ticks were collected from 102 animals in Ghaemshahr City in northern parts of Iran (88 sheep, 12 goats and 2 cattle). The prevalence of ticks infesting animals was Rh. sanguineus (82.35%), Rh. bursa (0.3%), Ixodes ricinus (I. ricinus) (15.2%), Boophilus annulatus (Bo. annulatus) (1.2%), Haemaphysalis punctata (Ha. punctata) (0.3%) and Ha. numidiana (0.6%). Eleven (55%) tick specimens were PCR positive against genome of Th. ovis (T. ovis). Sequence analysis of the PCR products confirmed presence of Th. ovis in one Rh. sanguinus (Telmadarraiy 2012). In this study, collected Rh. sanguineus ticks have been tested and other collected ticks have been neglected, this is not explained why the main role was directed for Rh. sanguineus. In studies by Shayan et al. 2007 and Telmadarraiy 2012 confirmed tick vectors should be addressed to the specific host and region of study to be able to get epizootical information.

There is a well planned study (Razmi et al. 2003) and clinically confirmed ill hosts have been regarded, then ticks on their body have been collected and their salivary glands were tested by staining method.

During a two year period 188 suspected cases of ovine theileriosis from 28 herds were clinically examined and investigated for the presence of Th. lestoquardi in appropriate blood smears and any tick species on body of sheep. In this study, 36.17% of sheep were infected to Th. lestoquardi with a parasitemia of 0.01–15%. There was no significant difference between the rate of parasitemia in sheep and the frequency of infected ticks. It has been found that 61.1% of the animals harboured Hy. anatolicum anatolicum, 33.42% Rh. sanguineus and 0.05% Hy. marginatum m. The examination of 345 tick salivary glands showed that 15% of salivary glands of Hy. anatolicum an. and (4%) of Rh. sanguineus contained Feulgen positive bodies (Razmi et al. 2003).

Regarding the present study, routine monitoring of infected ticks in endemic foci of protozoan infection could be an essential need in addition to monitoring of collected sera (blood) of infected animals and the epizootical information will be raised, then better understanding of tick and tick borne diseases and better planning for control measures for ticks could be achieved.

Acknowledgments

The present study was the result of a confirmed finalized official research project at Razi Institute and the author wishes to thank all cooperatives including Dr GR Habibi, Dr K Esmaeil-Nia, Dr GR Karimi, Dr M Namavari, Dr N Razmarae, Dr B Gh Goudarzi and Sh Rivaz. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdigoudarzi M, Noureddine R, Seitzer U, Ahmed J. rDNA-ITS2 Identification of Hyalomma, Rhipicephalus, Dermacentor and Boophilus spp. (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from different geographical regions of Iran. Advanced Studies in Biology. 2011;3(5):221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp BA, Baylis HA, Allsopp MTEP, Cavalier-Smith T, Bishop RP, Carrington DM, Sohanpal B, Spooner P. Discrimination between six species of Theileria using oligonucleotid probesd which detect small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Parasitol. 1993;107:157–165. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000067263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JA, Buening GM, Figueroa JV. Detection of Babesia bovis in ticks by the PCR assay. Abstracts of the 77th Annual Meeting, Conf. Res. Workers Anim. Dis; Chicago, IL. 1996. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R, Sohanpal BK, Kariuki DP, Young AS, Nene V, Baylis H, Allsopp BA, Spooner PR, Dolan TT, Morzaria SP. Detection of a carrier state in Theileria parva-infected cattle by the polymerase chain reaction. Parasitol. 1992;104:215–232. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000061655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop R, Sohanpal B, Allsopp BA, Spooner PR, Dolan TT, Morzaria SP. Detection of polymorphisms among Theileria parva stocks using repetitive, telomeric and ribosomal DNA probes and anti-schizont monoclonal antibodies. Parasitol. 1993;107:19–31. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000079361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher GO, Tim B. Quantitative studies on Theileria parva in the salivary glands of Rhipicephalus appendiculatus adults: quantitation and prediction of infection. Int J Parasitol. 1986;16(1):93–100. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(86)90071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PP, Conrad PA, ole-MoiYoi OK, Brown WC, Dolan TT. DNA probes detect T. parva in the salivary glands of R. appendiculatus ticks. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:590–594. doi: 10.1007/BF00931019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kok JB, d’Oliveira C, Jongejan F. Detection of the protozoan parasite Theileria annulata in Hyalomma ticks by the polymerase chain reaction. Exp Appl Acarol. 1993;17:839–846. doi: 10.1007/BF00225857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpy L. Revision Par des voies experimentales du genre Hyalomma Koch 1844. Archives del Institute d Hessarak. 1946;11:61–92. [Google Scholar]

- Delpy L. Notes Sur les Ixodides du genre Hyalomma Koch 1844. Archives del Institute d Hessarak. 1954:19. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Pena A, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Walker AR. Ticks of domestic animals in the Mediterranean region: a guide to identification of species. University of Zaragoza; Spain: 2004. published by: [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JV, Hernandez R, Buening GM. Use of polymerase chain reaction assay to detect Babesia bigemina in the tick Boophilus microplus. Abstacts 73rd Annual Meeting, Conf Res Worker Anim Dis; Chicago IL. 1992. p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JV, Cheives LP, Johnson GS, Buening GM. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction based assay for the detection of Babesia bigemina, Babesia bovis and Anaplasma marginale DNA in bovine blood. Vet Parasitol. 1993;50:69–81. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(93)90008-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedhoff KT. Tick-borne diseases of sheep and goats caused by Babesia, Theileria or Anaplasma spp. Parassitologia. 1997;39(2):99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisaki K, Irvin AD, Voigt WP, Leitch BL, Morzaria SP. The Establishment of Infection in the Salivary glands of Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks by transplantation of Kinetes of Theileria parva and the potential use of the method for parasite cloning. Int J Parasitol. 1988;18(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge NL, Kocan KM, Blouin EF, Murphy GL. Developmental studies of Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in male Dermacentor andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) infected as adults by using nonradioactive in situ hybridization and microscopy. J Med Entomol. 1996;33(6):911–920. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.6.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill HS, Walker AR. The salivary glands of Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum: nature of salivary gland components and their role in tick attachment and feeding. Int J Parasitol. 1988;18(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi GR, Hashemi-Fesharki R, Bordbar N. Detection of Babesia ovis using polymerase chain reaction. Archives of Razi Ins. 2004;57:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi-Fesharki R. Tick-borne diseases of sheep and goats and their related vectors in Iran. Parassitologia. 1997;39(2):115–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi-Fesharki R, Abdigoudarzi M, Esmaeil-Nia K. An Illustrated guide to the Ixodidae ticks of Iran. Veterinary Organization of Iran; Tehran: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogstraal H. 1956. African Ixodoidea, 1-Ticks of Sudan. Research Report NM 005 050.29.06.

- Kaplan, et al. ‘One Health’ and parasitology, editorial in Parasites and Vectors. 2009;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-36. available at: http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/2/1/36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvar E, Ilhan T, Katzer F, Wilkie G, Hooshmand-Rad P, Brown D. Detection of Theileria lestoquardi (hirci) in ticks, sheep, and goats using polymerase chain reaction. Ann New-York Acad Sc. 1998a;849:52–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvar E, Wilkie G, Katzer F, Brown CG. Theileria lestoquardi maturation and quantification in Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum ticks. Parasitology. 1998b;117(3):255–263. doi: 10.1017/s0031182098002960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvar E, Ilhan T, Katzer F, Hooshmand-Rad P, Zweygarth E, Gerstenberg C, Phipps P, Brown CG. Detection of Theileria annulata in cattle and vector ticks by PCR using the Tams1 gene sequences. Parasitol. 2000;120:245–254. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocan KM, Wickwire KB, Ewing SA, Hair JA, Barron SJ. Preliminary studies of the development of Anaplasma marginale in salivary glands of adult, feeding Dermacentor andersoni ticks. Am J Vet Res. 1988;49(7):1010–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebisch A, Rahman MS, Hoogstraal H. In progress in acarology, volume 1, ecology and behaviour of ticks. 1978. Tick faunna of Egypt with special reference to studies on Hyalomma anatolicum anatolicum, the natural vector of cattle theileriosis; pp. 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shayan P, Hooshmand E, Rahbari S, Nabian S. Determination of Rhipicephalus spp. as vectors for Babesia ovis in Iran. Parasitol Res. 2007;101(4):1029–1033. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparagano OAE, Allsopp MTEP, Mank RA, Rijpkema SGT, Figueroa JV, Jongejan F. Molecular detection of Pathogen DNA in Ticks (Acari: Ixodidae): A review. Exp Appl Acarol. 1999;23:929–960. doi: 10.1023/a:1006313803979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telmadarraiy Z, Oshaghi MA, Hosseini-Vasoukolaei N, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Babamahmoudi F, Mohtarami F. First molecular detection of Theileria ovis in Rhipicephalus sanguineus tick in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5(1):29–32. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60240-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt WP, Mwaura SN, Njihia GM, Nyaga SG, Young AS. Detection of Theileria parva in the Salivary glands of Rhipicephalus appendiculatus: evaluation of staining methods. Parasitol Res. 1995;81(1):74–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00932420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AR, McKellar SB. Observations on the separation of Theileria sporozoites from ticks. Int J Parasitol. 1983;13(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(83)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt D, Sparagano O, Brown CG, Walker AR. Use of the PCR for identification and quantification of Theileria parva protozoa in R. appendiculatus. Parasitol Res. 1997;83:359–363. doi: 10.1007/s004360050262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H, Luo J.2007Ticks of small ruminants in China Parasitol Res 101Suppl 2S187–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]