Abstract

A proportion of individuals vaccinated with live attenuated Oka varicella-zoster virus (VZV) vaccine subsequently develop attenuated chicken pox and/or herpes zoster. To determine whether postvaccination varicella infections are caused by vaccine or wild-type virus, a simple method for distinguishing the vaccine strain from wild-type virus is required. We have developed a TaqMan real-time PCR assay to detect and differentiate wild-type virus from Oka vaccine strains of VZV. The assay utilized two fluorogenic, minor groove binding probes targeted to a single nucleotide polymorphism in open reading frame 62 that distinguishes the Oka vaccine from wild-type strains. VZV DNA could be genotyped and quantified within minutes of thermocycling completion due to real-time monitoring of PCR product formation and allelic discrimination analysis. The allelic discrimination assay was performed in parallel with two standard PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) methods on 136 clinical and laboratory VZV strains from Canada, Australia, and Japan. The TaqMan assay exhibited a genotyping accuracy of 100% and, when compared to both PCR-RFLP methods, was 100 times more sensitive. In addition, the method was technically simpler and more rapid. The TaqMan assay also allows for high-throughput genotyping, making it ideal for epidemiologic study of the live attenuated varicella vaccine.

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is the etiological agent of varicella chicken pox and herpes zoster (HZ). Both varicella and HZ are self-limiting infections in healthy individuals but may cause more severe disease in immunocompromised hosts (2, 8, 23, 38).

A live attenuated Oka vaccine (V-Oka) strain was created in 1974 by the repeated passage of a Japanese clinical isolate in tissue culture (34). The vaccine was licensed in the United States in 1995 (2, 4) and in Canada in 1998 (27) and is currently used in many other countries (3, 40). Extensive clinical trials have shown the vaccine to be highly effective in both healthy and immunocompromised individuals (11, 19, 30, 33). However, a low incidence of superinfection with wild-type (WT) strains after immunization, termed breakthrough varicella, has been well documented (3, 10, 21, 39). Vaccine-associated rash occurs in 4 to 7% of healthy individuals (4, 40) and in up to 40% of leukemic vaccinees (10, 11). The vaccine strain does establish neuronal latency, and hence, reactivation of vaccine virus in and transmission from healthy and immunocompromised individuals is possible (11, 20, 21). As the number of vaccinees is increasing worldwide (31), the clinical management of HZ is becoming more complex. Given the fact that the vaccine virus is less pathogenic (39) and also less transmissible than WT virus (37), a timely differentiation of vaccine or WT disease would be clinically useful in situations with pregnant or immunocompromised household or hospital contacts, where prompt postexposure treatment may be indicated.

The original method used to differentiate WT and vaccine VZV was restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of genomic viral DNA (14). However, this method is technically demanding and depends on virus isolation. Other more rapid methods have been devised, including single-stranded conformational polymorphism analysis (26), long PCR (35), PCR-RFLP analysis (12, 17, 25, 32), and LightCycler real-time PCR (25, 36). Of these methods, PCR-RFLP is the most widely used; however, these protocols require postamplification manipulation and are technically involved. In contrast, discrimination of WT and vaccine strains by a TaqMan real-time allelic discrimination system eliminates the need for postamplification steps and is less technically demanding and more rapid than conventional PCR. This report describes the use of TaqMan real-time allelic discrimination PCR, with minor groove binding (MGB) probes, for single-tube detection and genotyping of VZV DNA. The MGB molecules effectively raise the melting temperature of oligonucleotides by binding to the minor groove of template DNA (16), allowing use of shorter probes for real-time PCR. Thus, in an allelic discrimination assay, a single base mismatch between the template and the shorter MGB probe causes more destabilization than would a single base mismatch with a larger probe, allowing for more-accurate single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral strains and DNA isolation.

A total of 144 clinical and laboratory VZV strains were available for testing. Of these samples, 8 isolates did not amplify by any of the three PCR methods and were not included in subsequent analysis. The samples consisted of 49 isolates and 11 vesicular swabs from the virology laboratory at the Children and Women's Health Center of British Columbia (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), 22 isolates from St. Paul's Hospital (Chris Sherlock, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), 51 isolates from the British Columbia Center for Disease Control (Gail McNab, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), 8 isolates from the Prince of Wales Hospital (William Rawlinson, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia), the Varivax V-Oka strain (Merck, Kirkland, Quebec, Canada), and the parental Oka (P-Oka) strain from Anne Gershon (Columbia University, New York, N.Y.). In addition, a vesicular scraping from a vaccinated 2-year-old girl was collected from the dermatology clinic of British Columbia Children's Hospital. Isolates were collected between 1994 and 2003 (excluding the P-Oka strain, which was isolated in 1974) from cases of both HZ and varicella. For clinical specimens and isolates, DNA was extracted from 200 μl of the sample with a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) per the manufacturer's instructions. DNA was eluted in 100 μl of buffer EB (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5) and was stored at −20°C until use.

RFLP analysis.

Two RFLP methods were carried out on all samples for comparison with results obtained from the TaqMan assay. The two methods have been described elsewhere (17, 24). Briefly, two sets of primers were used to amplify a 222-bp segment in open reading frame (ORF) 54 containing a BglI site and a 350-bp segment in ORF 38 containing a PstI site. The two PCR products were then combined and digested separately with BglI and PstI. WT viruses were generally PstI+/BglI− and PstI+/BglI+, whereas the vaccine was identified by the PstI−/BglI+ RFLP pattern. The second method involves amplification of a 268-bp segment that contained an SNP at position 106262 (all nucleotide positions cited are with reference to the Dumas strain) (6) in ORF 62. The amplicon was then digested with SmaI, and the vaccine-type viruses were identified by the additional SmaI site in the vaccine strain with reference to WT strains. Both PCRs were carried out in 50-μl reaction volumes with an MJ Research PTC-200 thermocycler (Scarborough, Ontario, Canada). GeneAmp PCR gold buffer, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, MgCl2, and AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.). PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in either 2% (ORF 38 and 54) or 4% (ORF 62) agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

PCR standards for real-time PCR.

Two primers (forward, 5′-ATC CGG TGG ACA CAC AGA AAG-3′; reverse, 5′-AGG CTA TGA GCC GTC GAT ACG-3′) were used to amplify a 215-bp segment flanking the amplicon used for real-time PCR analysis. The PCR product obtained was purified with the QIAquick PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen) and then cloned into the pCR2.1 TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The plasmid was extracted with the QIAprep plasmid mini kit (Qiagen). The plasmid was quantified by spectrophotometry, diluted in Tris-EDTA buffer, and stored at −80°C until use.

Real-time PCR.

Two primers were designed to amplify a 62-bp product encompassing an SNP at position 107252 (forward primer, VZ62TF, 5′-ACT GGA GCC CGT TGC CTC-3′; reverse primer, VZ62TR, 5′-TCC TAC AGA GTC TCC GCA GAG C-3′). Two fluorogenic MGB probes were designed with different fluorescent dyes to allow single-tube genotyping. One probe was targeted to WT strains (WT-VZ62T, 5′-6FAM-TTG CCA GCA TGG C-MGB-3′), and one was targeted to V-Oka strains (O-VZ62T, 5′-VIC-TTG CCG GCA TGG C-MGB). Primer and probe design was performed by using Primer Express software, version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems), and sequence homogeneity was confirmed by comparison to all available sequences on the GenBank database by using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

Real-time PCR was performed in 25-μl reaction mixtures containing 12.5 μl of TaqMan universal master mix (Applied Biosystems), 300 nM concentrations of each primer, 250 nM WT probe, 200 nM vaccine probe, and 5 μl of sample DNA. Thermocycling was performed on the Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) and consisted of 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C for AmpliTaq Gold activation, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Analysis was performed by using SDS, version 2.0, software. VZV DNA quantification was done by comparing the cycle threshold (CT) value (PCR cycle at which the reporter fluorescence reaches 20 standard deviations above background emissions) of the samples to the CT versus plasmid quantity standard curve. Samples were considered positive if they had CT values of ≤39 cycles. Each sample was verified visually by examining the PCR curves generated to eliminate false positives due to aberrant light emission. End-point allelic discrimination genotyping was performed by visually inspecting a plot of the RN (fluorescence) from the WT probe versus the RN from the vaccine probe generated from the post-PCR fluorescence read. DNA from American Type Culture Collection strains of herpes simplex viruses I and II, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus 6 did not amplify by any of the three PCR methods (data not shown).

RESULTS

The P-Oka strain, the clinical isolate which was attenuated to create the V-Oka strain, was sequenced at position 107252, confirming the T-to-C transition identified in a past study (12). This SNP was chosen for the development of a TaqMan real-time PCR genotyping assay.

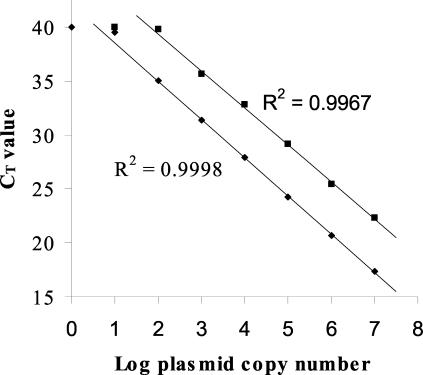

To assess the sensitivity of the TaqMan assay, 1 to 107 plasmid copies of both WT and vaccine plasmid standards were amplified. The linear range of detection was determined to be 107 to 102 plasmid copies for the WT probe and 107 to 103 plasmid copies for the vaccine probe (Fig. 1). The sensitivity of the TaqMan assay was also compared to that of the PCR-RFLP methods by amplifying serial dilutions of the positive-control clinical isolate DNA. Using the PCRs from both RFLP methods, bands were visible down to the 102-fold dilution, whereas the TaqMan assay detected down to the 104-fold dilution for both duplicates (estimated 100-fold-greater sensitivity).

FIG. 1.

Real-time PCR plasmid standard curve for WT and V-Oka assays. Dilutions of both WT (♦) and V-Oka (▪) plasmid standards ranging from 107 to 1 copy/reaction were amplified by the TaqMan method. The resulting CT values were plotted as a function of the log plasmid copy number. Each data point is the average of the results for 5 replicate reactions performed simultaneously. The linear ranges of detection for the WT and V-Oka probes were 102 to 107 and 103 to 107 plasmid copies/reaction, respectively.

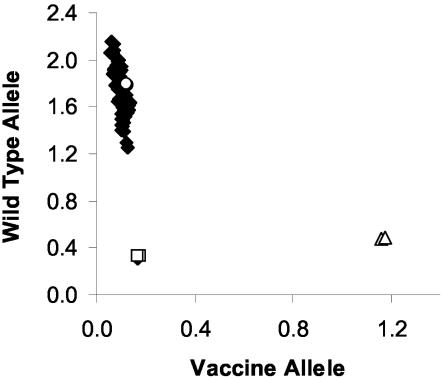

The TaqMan assay and two PCR-RFLP methods were used to genotype 125 Canadian strains, 8 Australian strains, the P-Oka strain, and the V-Oka strain. A representative allelic discrimination plot used to assign the genotypes is displayed in Fig. 2. The two genotypes were easily discriminated by the distribution along either the WT probe or V-Oka probe axis. Samples that fail to amplify clustered with the control samples containing no template. The results of the genotyping from the three methods are summarized in Table 1. The results from the TaqMan method corresponded with both RFLP methods for 134 of the total 135 strains tested. The one discrepancy was due to the mistyping of the P-Oka strain as vaccine by the ORF 38 and 54 method. The ORF 62 RFLP and TaqMan methods typed the P-Oka strain correctly as WT. It was thus concluded that the TaqMan method successfully genotyped all 135 strains correctly (specificity of 100%).

FIG. 2.

Allelic discrimination plot of clinical isolates and V-Oka strain. DNA from clinical isolates (♦), V-Oka DNA (▵), WT DNA (○), and controls containing no template (□) were amplified in duplicate by the TaqMan method. Data were plotted by using the absolute fluorescence of each reporter dye probe. In the depicted run, all samples except one which failed to amplify were identified as WT virus, and the V-Oka DNA was identified as vaccine DNA.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of TaqMan genotyping method to two RFLP methods

| Source | Sample type | n | Restriction enzyme site in ORF:

|

TaqMan genotyping result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38 | 54 | 62 | ||||

| Merck | V-Oka (Varivax) | 1 | PstI− | BglI+ | SmaI+ | Vaccine |

| Japan | P-Oka strain | 1 | PstI− | BglI+ | SmaI− | WT |

| Canada | Isolate | 90 | PstI+ | BglI− | SmaI− | WT |

| Canada | Isolate | 26 | PstI+ | BglI+ | SmaI− | WT |

| Canada | Vesicle swab | 4 | PstI+ | BglI− | SmaI− | WT |

| Canada | Vesicle swab | 5 | PstI+ | BglI+ | SmaI− | WT |

| Canada | Vesicle scrapinga | 1 | PstI− | BglI+ | SmaI+ | Vaccine |

| Australia | Isolate | 7 | PstI+ | BglI− | SmaI− | WT |

| Australia | Isolate | 1 | PstI− | BglI− | SmaI− | WT |

Vesicular scraping was obtained from zoster-like vesicles in an immunized individual.

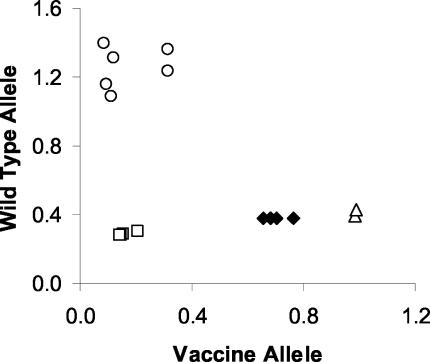

Following development and verification, the TaqMan assay was used to investigate a case of suspected HZ in a vaccinated individual. A 2-year-old girl presented with a 2-day history of asymptomatic skin lesions on the left arm that were increasing in number. She was otherwise healthy. There was a history of contact with chicken pox and HZ in the recent past. She was immunized with Varivax in March 2002 at 12 months of age. Neither her mother nor her pediatrician could recall the site of the immunization. Physical examination revealed erythematous papules and plaques with superimposed tiny vesicles extending from the left deltoid area to the flexor surface of the wrist.

A diagnosis of HZ involving the left C6 dermatome was confirmed by positive direct immunofluorescence performed on cells obtained by scraping the base of a vesicle. Viral culture was negative. The specimen was positive for vaccine virus by both the TaqMan method (Fig. 3) and the two RFLP methods. The eruption resolved without treatment.

FIG. 3.

Allelic discrimination plot of VZV DNA isolated from zoster lesions in a vaccinated individual. DNA was extracted from a vesicle scraping obtained from a vaccinated individual with HZ. Specimen DNA from two DNA extractions (♦), V-Oka DNA (▵), WT DNA controls (○), and controls containing no template (□) were amplified in duplicate by the TaqMan method. Data were plotted by using the absolute fluorescence of each reporter dye probe. The clinical VZV DNA specimen clustered with the V-Oka DNA and was identified as vaccine DNA.

The proportion of Canadian strains that were BglI+ was 25% (31 of 125), and 100% were PstI+. Seven of eight Australian isolates were PstI+/BglI−, and one isolate was type PstI−/BglI−.

DISCUSSION

PCR-RFLP has become the most widely used method for genotyping VZV, as this method offers comparable accuracy to VZV genomic RFLP but is less complex and more sensitive (17). Although these methods require less technician time than genomic RFLP, they still require, on average, two working days to complete and require postamplification manipulations, bringing about the possibility of PCR product carryover, resulting in false-positive results. The TaqMan system has been shown to be rapid, sensitive, and accurate for the detection of many viruses (5, 22, 28) and dispenses with post-PCR manipulations and a number of the technical problems of PCR-RFLP methods.

The genotyping results from the TaqMan assay described herein corresponded to those obtained from the two PCR-RFLP methods for 135 of the 136 strains tested. As the single discrepancy between the methods was thought to arise from mistyping by the ORF 38 and 54 RFLP method, the genotyping accuracy of the TaqMan assay was concluded to be 100%. The TaqMan method was also performed more rapidly and with a greater sensitivity than both PCR-RFLP methods used. The TaqMan method was also able to accurately quantify both WT and V-Oka VZV DNA with a linear range of detection of 103 to 107 plasmid copies/PCR.

TaqMan PCR does not require postamplification steps, as the formation of PCR product is monitored by real-time measurement of reporter dye fluorescence, and thus, there is no need for opening reaction vessels. To further eliminate the chance of false positives, the AmpErase system was used. This system involves the incorporation of dUTPs in place of dTTPs in all PCR products; at the beginning of each run, uracil-containing nucleic acids, including PCR products, are digested by the uracil-N-glycosylase enzyme during the 50°C step.

The present assay was designed to conform to standard thermocycling conditions (40 cycles containing a 60°C annealing and extension step), allowing the assay to be performed simultaneously with other assays, making it ideal in a clinical laboratory where numerous assays for different pathogens are being performed.

In PCR-RFLP methods, much of the time needed is devoted to postamplification steps: verifying the presence of PCR product by gel electrophoresis, restriction endonuclease digestion, and restriction pattern visualization by gel electrophoresis. The TaqMan method, by contrast, is less time-consuming because analysis of amplification can be done within minutes of thermocycling completion with the SDS software. To increase the throughput of the method for genotyping, thermocycling can be performed on several traditional thermocyclers and a 6-min post-PCR read can be done on the ABI Prism machine. This allows for an extremely high throughput with either the 96- or 384-well format. Thus, the assay is limited largely by the time required for DNA extraction; using the presently described procedure, up to 36 samples could be extracted, amplified on the ABI Prism machine in duplicate, quantified, and genotyped by one technician in ∼6 h.

Our real-time VZV PCR assay will allow the sensitive and robust detection of the viral genome in clinically important specimens, such as cerebrospinal fluid and blood, aiding in the management of patients with cerebral or severe systemic VZV disease where antiviral treatment may be necessary. In addition to early viral detection, TaqMan PCR can be used to determine viral load and is thus valuable for monitoring disseminated disease progression and response to antiviral therapy in clinical and research settings. This approach has been successfully used for a number of viruses including VZV, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and adenovirus (1, 7, 9). As demonstrated by the plasmid standard curve in Fig. 1, our assay is capable of quantifying VZV DNA and could be used for the mentioned applications, if desired.

Disease caused by V-Oka infection is milder than that caused by WT strains (39), and the virus is also less transmissible (37). Therefore, in a hospital setting, the timely distinction of WT and vaccine virus provides a valuable guide to the management of exposed immunocompromised or pregnant patients, for whom postexposure prophylaxis may be indicated. Since continuing epidemiological information about the frequency and seriousness of vaccine-related illness will provide baseline data for ongoing modifications of infection control guidelines in the hospital setting, the effective monitoring of adverse effects by real-time PCR would benefit patient management (31).

The success of the TaqMan method relies on the detection of a single base substitution of a C for a T at position 107252 in the V-Oka strain. It is possible that a subset of WT strains exist which carry the same V-Oka SNP or vice versa. However, from the 134 strains tested, it initially appears that the WT strains do not contain the SNP. As for V-Oka preparations containing the WT sequence, the SNP at position 107252 results in an amino acid substitution of a serine for a glycine in the V-Oka IE62, an immediate-early transcriptional activator. The activity of the V-Oka IE62 has been shown to be significantly lower than that of P-Oka IE62 in vitro (12), suggesting that altered IE62 function is selected for during vaccine production and would thus be less likely to be absent in vaccine preparations. In addition, the SNP used to design the assay appears to be stable after culture in a human host, as the VZV DNA recovered from the zoster lesions of a vaccinated individual were identified as the vaccine type by the TaqMan and PCR-RFLP methods.

Of the 125 Canadian WT strains tested, 25% were BglI+ and 100% were PstI+. This suggests, as expected, that Canadian strains are more like United States, United Kingdom, and German strains, of which 19, 20, and 6%, respectively, are BglI+ (13, 18, 29), than Japanese strains, of which 100% are BglI+ and up to 37% are PstI− (15, 18, 24, 32). Interestingly, one Australian isolate was found to be PstI−/BglI−, a genotype that has not been previously reported.

In summary, the TaqMan assay exhibited exquisite genotyping accuracy, was highly reproducible, was more sensitive and rapid than both PCR-RFLP used, and was performed without postamplification steps, making the TaqMan method ideal for clinical and epidemiological use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Gershon for the generous donation of the P-Oka strain. We also thank Colleen Trombley and Mary Jane Margach for technical advice and Andrew Pollard for experimental advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aitken, C., K. Hawrami, C. Miller, W. Barrett Muir, M. Yaqoob, and J. Breuer. 1999. Simultaneous treatment of cytomegalovirus and varicella zoster infections in a renal transplant recipient with ganciclovir: use of viral load to monitor response to treatment. J. Med. Virol. 59:412-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. 1995. Recommendations for the use of live attenuated varicella vaccine. Pediatrics 95:791-796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asano, Y., S. Suga, T. Yoshikawa, I. Kobayashi, T. Yazaki, M. Shibata, K. Tsuzuki, and S. Ito. 1994. Experience and reason: twenty-year follow-up of protective immunity of the Oka strain live varicella vaccine. Pediatrics 94:524-526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1996. Prevention of varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 45(RR-15):1-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohrs, R. J., J. Randall, J. Smith, D. H. Gilden, C. Dabrowski, H. van Der Keyl, and R. Tal-Singer. 2000. Analysis of individual human trigeminal ganglia for latent herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus nucleic acids using real-time PCR. J. Virol. 74:11464-11471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison, A. J., and J. E. Scott. 1986. The complete DNA sequence of varicella-zoster virus. J. Gen. Virol. 67(Pt 9):1759-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Jong, M. D., J. F. Weel, T. Schuurman, P. M. Wertheim-van Dillen, and R. Boom. 2000. Quantitation of varicella-zoster virus DNA in whole blood, plasma, and serum by PCR and electrochemiluminescence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2568-2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman, S., W. T. Hughes, and C. B. Daniel. 1975. Varicella in children with cancer: seventy-seven cases. Pediatrics 56:388-397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuta, Y., F. Ohtani, H. Sawa, S. Fukuda, and Y. Inuyama. 2001. Quantitation of varicella-zoster virus DNA in patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome and zoster sine herpete. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2856-2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gershon, A. A., and S. P. Steinberg. 1989. Persistence of immunity to varicella in children with leukemia immunized with live attenuated varicella vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 320:892-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon, A. A., S. P. Steinberg, and L. Gelb. 1986. Live attenuated varicella vaccine use in immunocompromised children and adults. Pediatrics 78:757-762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomi, Y., T. Imagawa, M. Takahashi, and K. Yamanishi. 2000. Oka varicella vaccine is distinguishable from its parental virus in DNA sequence of open reading frame 62 and its transactivation activity. J. Med. Virol. 61:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawrami, K., and J. Breuer. 1997. Analysis of United Kingdom wild-type strains of varicella-zoster virus: differentiation from the Oka vaccine strain. J. Med. Virol. 53:60-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayakawa, Y., T. Yamamoto, K. Yamanishi, and M. Takahashi. 1986. Analysis of varicella-zoster virus DNAs of clinical isolates by endonuclease HpaI. J. Gen. Virol. 67(Pt 9):1817-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hondo, R., Y. Yogo, M. Yoshida, A. Fujima, and S. Itoh. 1989. Distribution of varicella-zoster virus strains carrying a PstI-site-less mutation in Japan and DNA change responsible for the mutation. Jpn. J. Exp Med. 59:233-237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kutyavin, I. V., E. A. Lukhtanov, H. B. Gamper, and R. B. Meyer. 1997. Oligonucleotides with conjugated dihydropyrroloindole tripeptides: base composition and backbone effects on hybridization. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3718-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaRussa, P., O. Lungu, I. Hardy, A. Gershon, S. P. Steinberg, and S. Silverstein. 1992. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of polymerase chain reaction products from vaccine and wild-type varicella-zoster virus isolates. J. Virol. 66:1016-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LaRussa, P., S. Steinberg, A. Arvin, D. Dwyer, M. Burgess, M. Menegus, K. Rekrut, K. Yamanishi, and A. Gershon. 1998. Polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of varicella-zoster virus isolates from the United States and other parts of the world. J. Infect. Dis. 178(Suppl. 1):S64-S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaRussa, P., S. Steinberg, and A. A. Gershon. 1996. Varicella vaccine for immunocompromised children: results of collaborative studies in the United States and Canada. J Infect. Dis. 174(Suppl. 3):S320-S323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaRussa, P., S. Steinberg, F. Meurice, and A. Gershon. 1997. Transmission of vaccine strain varicella-zoster virus from a healthy adult with vaccine-associated rash to susceptible household contacts. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1072-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaRussa, P., S. P. Steinberg, E. Shapiro, M. Vazquez, and A. A. Gershon. 2000. Viral strain identification in varicella vaccinees with disseminated rashes. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:1037-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung, E., B. K. Shenton, G. Jackson, F. K. Gould, C. Yap, and D. Talbot. 2002. Use of real-time PCR to measure Epstein-Barr virus genomes in whole blood. J. Immunol. Methods 270:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locksley, R. M., N. Flournoy, K. M. Sullivan, and J. D. Meyers. 1985. Infection with varicella-zoster virus after marrow transplantation. J Infect. Dis. 152:1172-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loparev, V. N., T. Argaw, P. R. Krause, M. Takayama, and D. S. Schmid. 2000. Improved identification and differentiation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) wild-type strains and an attenuated varicella vaccine strain using a VZV open reading frame 62-based PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3156-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loparev, V. N., K. McCaustland, B. P. Holloway, P. R. Krause, M. Takayama, and D. S. Schmid. 2000. Rapid genotyping of varicella-zoster virus vaccine and wild-type strains with fluorophore-labeled hybridization probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4315-4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori, C., R. Takahara, T. Toriyama, T. Nagai, M. Takahashi, and K. Yamanishi. 1998. Identification of the Oka strain of the live attenuated varicella vaccine from other clinical isolates by molecular epidemiologic analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 178:35-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee on Immunization. 1999. Statement on recommended use of varicella virus vaccine. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 25:1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitsche, A., N. Steuer, C. A. Schmidt, O. Landt, H. Ellerbrok, G. Pauli, and W. Siegert. 2000. Detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA by real-time quantitative PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2734-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauerbrei, A., U. Eichhorn, S. Gawellek, R. Egerer, M. Schacke, and P. Wutzler. 2003. Molecular characterisation of varicella-zoster virus strains in Germany and differentiation from the Oka vaccine strain. J. Med. Virol. 71:313-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheifele, D. W., S. A. Halperin, and F. Diaz-Mitoma. 2002. Three-year follow up of protection rates in children given varicella vaccine. Can J. Infect. Dis. 13:382-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharrar, R. G., P. LaRussa, S. A. Galea, S. P. Steinberg, A. R. Sweet, R. M. Keatley, M. E. Wells, W. P. Stephenson, and A. A. Gershon. 2000. The postmarketing safety profile of varicella vaccine. Vaccine 19:916-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takada, M., T. Suzutani, I. Yoshida, M. Matoba, and M. Azuma. 1995. Identification of varicella-zoster virus strains by PCR analysis of three repeat elements and a PstI-site-less region. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:658-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi, M. 2001. 25 years' experience with the Biken Oka strain varicella vaccine: a clinical overview. Paediatr. Drugs 3:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi, M., T. Otsuka, Y. Okuno, Y. Asano, and T. Yazaki. 1974. Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of varicella in children in hospital. Lancet ii:1288-1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takayama, M., N. Takayama, N. Inoue, and Y. Kameoka. 1996. Application of long PCR method of identification of variations in nucleotide sequences among varicella-zoster virus isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2869-2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tipples, G. A., D. Safronetz, and M. Gray. 2003. A real-time PCR assay for the detection of varicella-zoster virus DNA and differentiation of vaccine, wild-type and control strains. J. Virol. Methods 113:113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsolia, M., A. A. Gershon, S. P. Steinberg, and L. Gelb. 1990. Live attenuated varicella vaccine: evidence that the virus is attenuated and the importance of skin lesions in transmission of varicella-zoster virus. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Varicella Vaccine Collaborative Study Group. J. Pediatr. 116:184-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vafai, A., and M. Berger. 2001. Zoster in patients infected with HIV: a review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 321:372-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vazquez, M., P. S. LaRussa, A. A. Gershon, S. P. Steinberg, K. Freudigman, and E. D. Shapiro. 2001. The effectiveness of the varicella vaccine in clinical practice. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:955-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White, C. J. 1997. Varicella-zoster virus vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:753-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]