Abstract

Infantile hemangioma is the most common vascular tumor in early childhood. Propranolol has been successfully used recently in a limited number of children with Infantile hemangioma. We present 6 cases of Infantile hemangioma, at a single dermatological center, which responded to oral propranolol with good results.

Keywords: Hemangioma, Propranolol, Vascular neoplasms

Abstract

O hemangioma da infância é o tumor vascular mais comum nessa faixa etária. Mais recentemente, propranolol oral tem sido usado com sucesso em um número limitado de crianças com hemangioma da infância. Nós apresentamos 6 casos de hemangioma da infância, provenientes de um único centro dermatológico, que apresentaram boa resposta ao tratamento com propranolol oral.

INTRODUCTION

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are the most common benign tumors in early childhood and usually have a non-harmful clinical course.1 Most hemangiomas become evident within the first few weeks of life and may be subtle at birth.2 About 10% of IH develop complications and require treatment, especially those located in the periocular, airway and perineal areas.1 Systemic corticosteroids have been the mainstay of complicated IH treatment. Recently, propranolol has shown excellent response in proliferative IH and has become an additional therapeutic option.3

We present 6 cases of IH, including subtypes such as PHACES syndrome, "beard hemangioma" and Cyrano's hemangioma which were successfully treated with oral propranolol at 2mg/kg per day every 12 hours.

CASE REPORT

1.1. Case 1

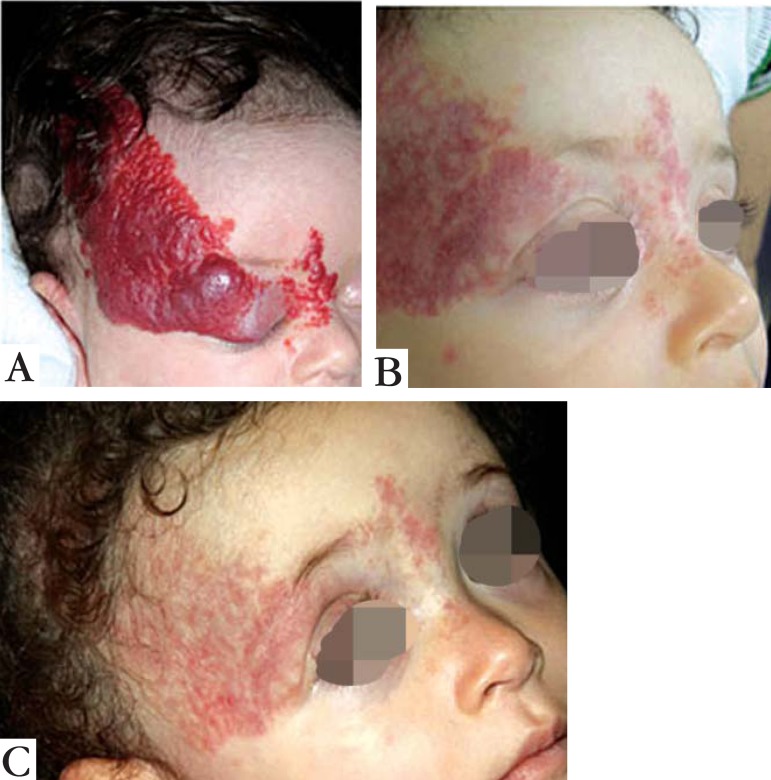

A 2-month-old girl born at term was referred to our clinic with a protuberant hemangioma on face, impinging on the superior right eyelid (Figure 1A). Propranolol was introduced, and the lesion reduced in size and had largely healed within 6 months (Figure 1B). This infant had an eye examination and impairment of visual function, strabismus, astigmatism or amblyopia were ruled out. At the age of 9 months, she developed a red telangiectatic macula in the previous hemangioma area (Figure 1C). It is being planned to taper off propranolol after the child is 1 year and 6 months of age.

FIGURE 1.

A. Hemangioma in superior right eyelid area; B. After 6 months of propranolol; C. Residual macula after 9 months of treatment

1.2. Case 2

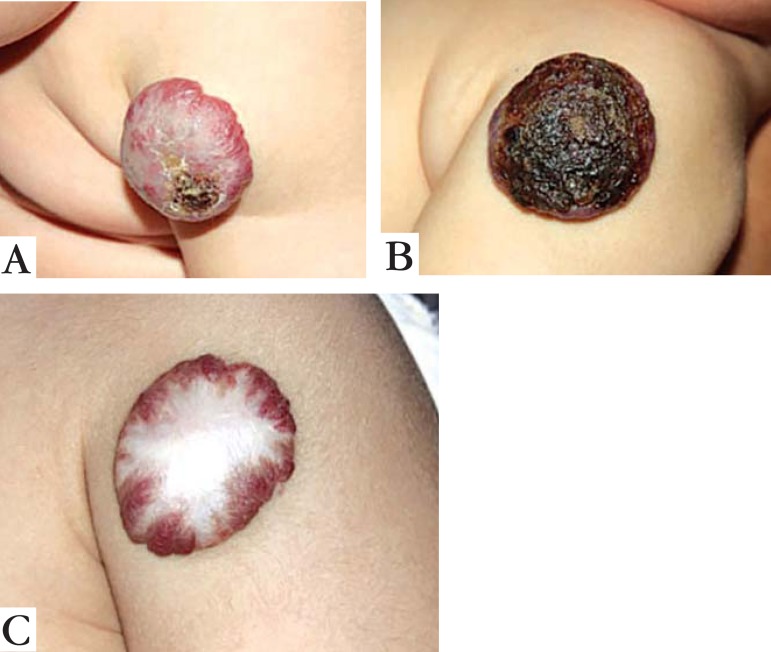

A 5-month-old boy born at term was referred to our clinic with a left arm hemangioma of 8.0 x 6.0 cm, presenting a lateral ulceration measuring 1.0 x 1.0 cm (Figure 2A). Despite management with gentamicin ointment dressings, the ulceration failed to heal. One month later it became larger and started to bleed, causing pain and discomfort to the infant (Figure 2B). Propranolol was initiated at the age of 6 months and there was a significant reduction in size of the ulcer within a week. Seven months later, the deep component was much reduced and the superficial part healed (Figure 2C). It is planned to wean off propranolol when the child is at least 1 year and 6 months of age.

FIGURE 2.

A. A 5-month old boy with hemangioma on his left arm; B. Spontaneous ulceration at 6 month age; C. Regression of hemangioma after 7 months of propranolol treatment

1.3. Case 3

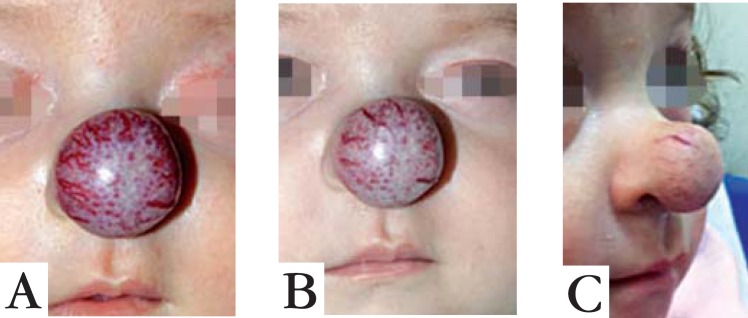

A 2-month old girl born at term was referred for management of a nasal IH, also known as "Cyrano's hemangioma" (Figure 3A). Propranolol was started and there was significant reduction in size and color of lesion within one month (Figure 3B). She is at the sixth month of oral propranolol treatment, and the lesion is still improving (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3.

A. Nasal hemangioma in 2-month-old girl; B. Significant decrease in size and color after one month of oral propranolol; C. At the sixth month of treatment, the lesion continues to improve with oral propranolol

1.4. Case 4

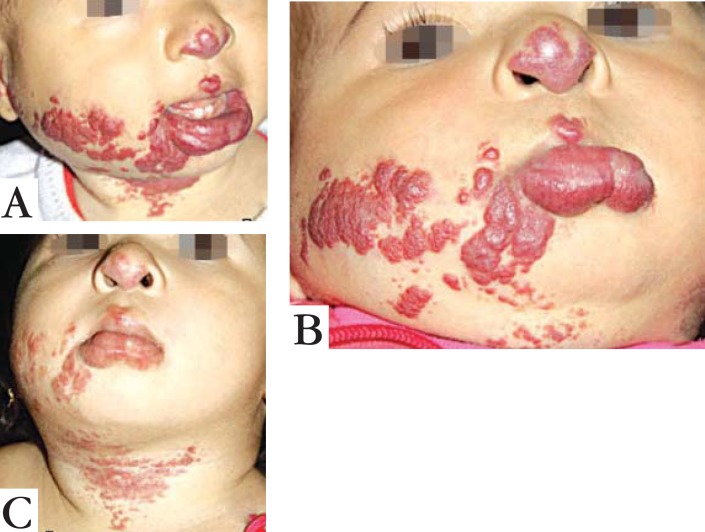

A 6-month old girl born at 35 weeks, was referred with a combined superficial and deep segmental IH (S3 and S4 involvement of PHACES syndrome) (Figure 4A). Recently she underwent a successful cardiac surgery for correction of an interventricular wall defect. We decided to investigate neurological and ophthalmological abnormalities, suspecting PHACES syndrome, and she was diagnosed with strabismus. We started propranolol at 8 months, with a rapid improvement of the hemangioma and strabismus within a month (Figure 4B). She was treated with propranolol until 1 year and 8 months of age, and four months later, the hemangioma remains without signs of recurrence (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 4.

A. PHACES Syndrome before treatment; B. Evident improve of hemangioma and strabismus after one month of treatment; C. No signs of recurrence 4 months after stopping propranolol

1.5. Case 5

A 2-month-old girl born at 33 weeks was referred for treatment of a large facial hemangioma, with total occlusion of the left eye (Figure 5A). Ophthalmological examination revealed no abnormalities, and propranolol was introduced at this age. The lesion reduced in size and had largely healed in 2 months (Figure 5B). She received propranolol until 1 year and 9 months of age, and 8 months later she remains free of the hemangioma, with only a few residual telangiectasias (Figure 5C).

FIGURE 5.

A. Large facial hemangioma before treatment; B. After 2 months of oral propranolol; C. Residual telangiectasias 8 months after end of therapy

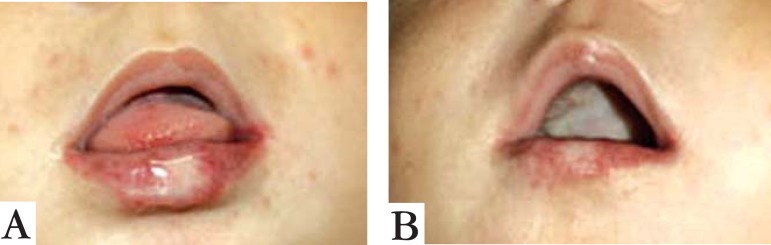

1.6. Case 6

A 5-month-old girl born at term was referred for investigation of a "beard hemangioma", which was progressively increasing in size, causing deformity in the neck area (Figure 6A). There was no difficulty in breathing or hoarseness, but radiological exams were performed to rule out internal hemangiomas, such as in the subglottic area. Ultrasound revealed parotid involvement of hemangioma, and the otorhinolaryngological examination was otherwise normal. We started oral propranolol at this age, and 2 months later she showed great response with decrease of neck volume and of the hemangioma located over the mandibular area (Figure 6B). Its is planned to wean off propranolol when she is 1 year and 6 months of age.

FIGURE 6.

A. “Beard hemangioma” causing neck deformity; B. Reduction of neck volume after 2 months of therapy

DISCUSSION

Infantile hemangioma has an incidence of up to 10% in white infants, occurring more frequently in premature and female infants.4 Of our 6 cases, 5 were girls and 2 were premature, consistent with published data.5 The mechanisms that control involution of IH are poorly understood; new evidence shows that apoptosis may be partially responsible.6 Léaute-Labrèze et al 3 recently reported a surprising response to treatment of IH with propranolol, which was confirmed by other studies.7,8

The therapeutic effect of propranolol in infantile hemangiomas is probably secondary to 3 different mechanisms: 1) vasoconstriction; 2) decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); 3) triggering of apoptosis of capillary endothelial cells.9

Few serious side effects and no deaths are described1 Prior to therapeutic and clinical cardiologic evaluation, echocardiogram and electrocardiogram were performed. Serious side effects include bronchospasms in asthmatic patients, hypoglycemia and restless sleep. We recommended to stop the treatment during episodes of bronchiolitis. We did not observe any side effects of beta-blockers.

In our cases, there was almost immediate cessation of proliferation of hemangioma in every patient, leading to considerable shortening of the natural course of the lesion.10 The initial dose of propranolol was 1mg/kg per day for the first week and then increased up to the maximum dosage of 2mg/kg per day.

These cases showed that propranolol was equally effective for the treatment of IHs in both sexes and in segmental and non segmental IHs. Ulcerating IH also showed a dramatic improvement.

We acknowledge that the number of patients in this study is limited, and data of more patients are needed before definitive conclusions can be reached. However, in this observational study, oral propranolol 2 mg/kg/day was a well-tolerated and effective treatment for IHs.

Footnotes

Work performed at the Pediatric Dermatology Unit, Teaching Hospital, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo (HC-FMUSP) - São Paulo (SP), Brazil.

Conflict of interest: None

Financial funding: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Léauté-Labrèze C, Prey S, Ezzedine K. Infantile haemangioma: Part II. Risks, complications and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1254–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drolet BA, Esterly NB, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas in children. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:173–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649–2651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garzon MC, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Haggstrom AN, Horii K, et al. Comparison of infantile hemangiomas in preterm and term infants: a prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1231–1232. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.9.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans DJ, Boezeman JB, Van de Kerkhof PC, Rieu PN, Van der Vleuten CJ. Differences between ulcerated and non-ulcerated hemangioma, a retrospective study of 456 patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:152–156. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razon MJ, Kräling BM, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J. Increased apoptosis coincides with onset of involution in infantile hemangioma. Microcirculation. 1998;5:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawley LP, Siegfried E, Todd JL. Propranolol treatment for hemangioma of infancy: risks and recommendations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:610–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manunza F, Syed S, Laguda B, Linward J, Kennedy H, Gholam K, et al. Propranolol for complicated infantile haemangiomas: a case series of 30 infants. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:466–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Angelo G, Lee H, Weiner RI. cAMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits the mitogenic action of vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor in capillary endothelial cells by blocking Raf activation . J Cell Biochem. 1997;67:353–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Della Nina BI, Oliveira ZN, Machado MC, Macea JM. Presentation, progression and treatment of cutaneous hemangiomas - Experience of the Outpatients Clinic of Pediatric Dermatology - Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:323–327. [Google Scholar]