Abstract

We report the case of a 28-year-old woman with Kindler syndrome, a rare form of epidermolysis bullosa. Clinically, since childhood, she had widespread pigmentary changes in her skin as well as photosensitivity and fragility of the skin and mucous membranes. The mucosal involvement led to an erosive stomatitis as well as esophageal, anal and vaginal stenoses, requiring surgical intervention. The diagnosis of Kindler syndrome was confirmed by DNA sequencing with compound heterozygosity for a nonsense/frameshift combination of mutations (p.Arg110X; p.Ala289GlyfsX7) in the FERMT1 gene.

Keywords: DNA mutational analysis, Epidermolysis bullosa, Photosensitivity disorders

Abstract

Nós relatamos uma paciente feminina de 28 anos com Síndrome de Kindler, uma forma rara de Epidermólise Bolhosa. Clinicamente, ela apresentava alterações cutâneas pigmentares disseminadas, fotossensibilidade e fragilidade da pele e das mucosas desde a infância. O envolvimento mucoso levou à estomatite erosiva e a estenoses esofágica, anal e vaginal, as quais necessitaram de intervenções cirúrgicas. O diagnóstico de Síndrome de Kindler foi confirmado por sequenciamento de DNA, que demonstrou heterozigose composta uma combinação de mutações uma nonsense e outra frameshift (p.Arg110X; p.Ala289GlyfsX7) no gene FERMT1.

INTRODUCTION

Kindler syndrome (KS) is a rare autosomal recessive disease characterized by trauma-induced blistering, poikiloderma, skin atrophy and photosensitivity.1,2 It can often overlap clinically (at least in the early stages) with dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa and is currently classified as a distinct form of intra-epidermal EB.3 The disorder results from mutations in the FERMT1 gene (also known as KIND1), which encodes the protein fermitin family homolog1 (also known as kindlin-1), a component of focal contact complexes at the dermal-epidermal junction, involved in epithelial-mesenchymal signaling via b1 integrin.4,5 Although light microscopy can be helpful, accurate diagnoses are best made by direct sequencing of the FERMT1 gene.

CASE REPORT

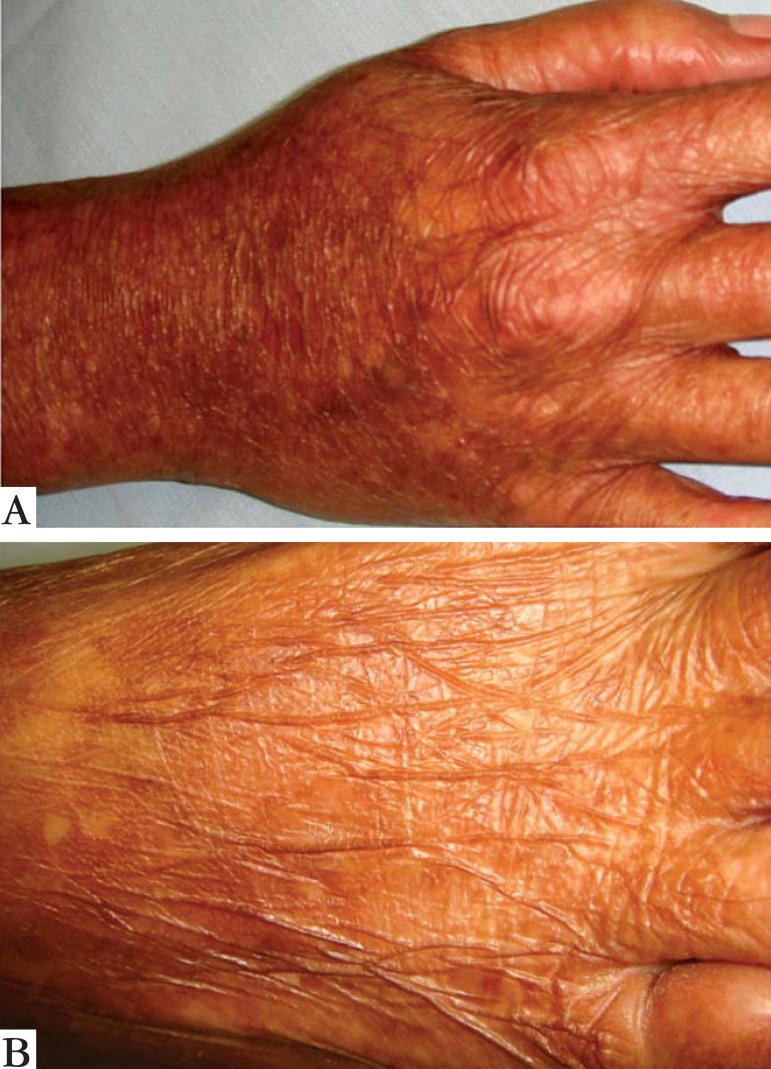

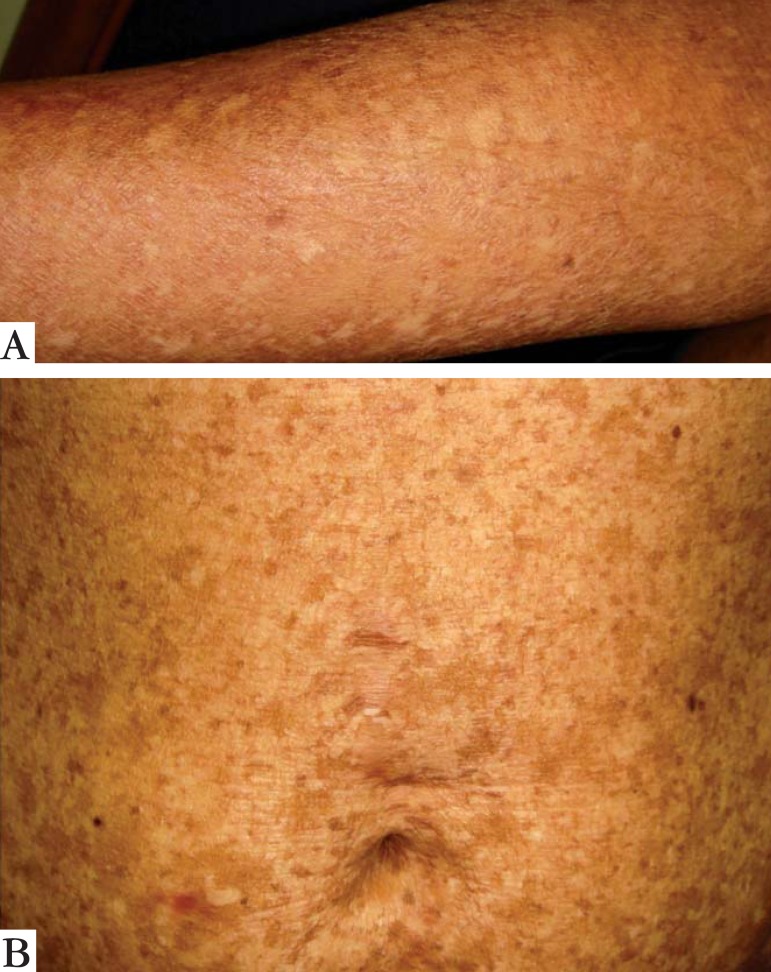

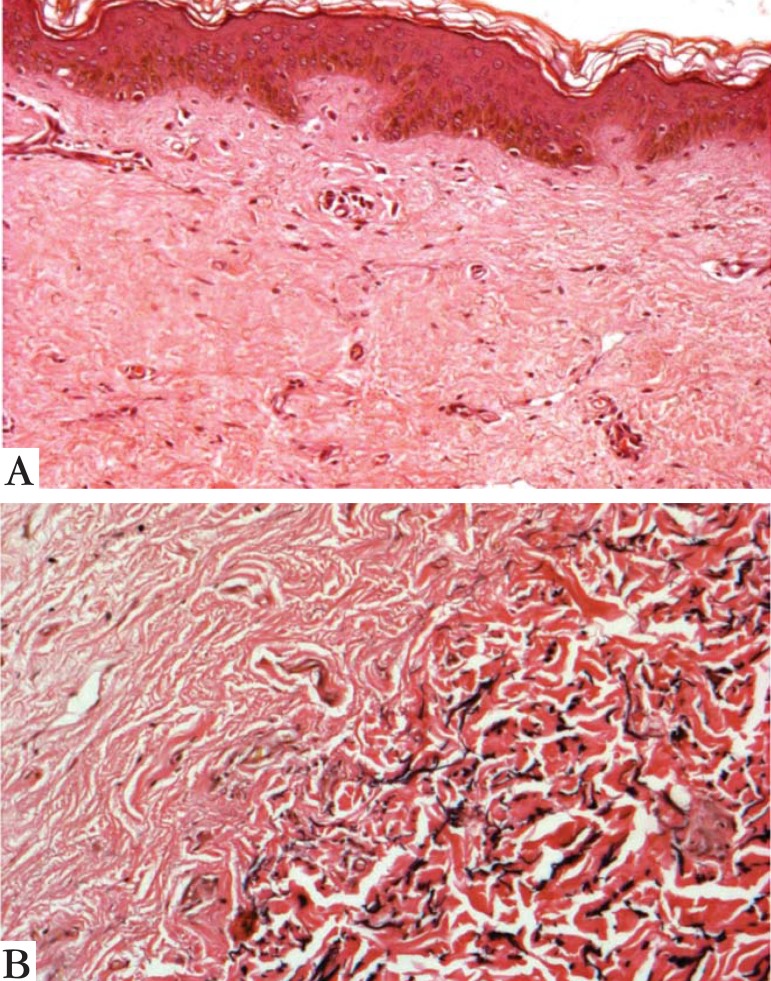

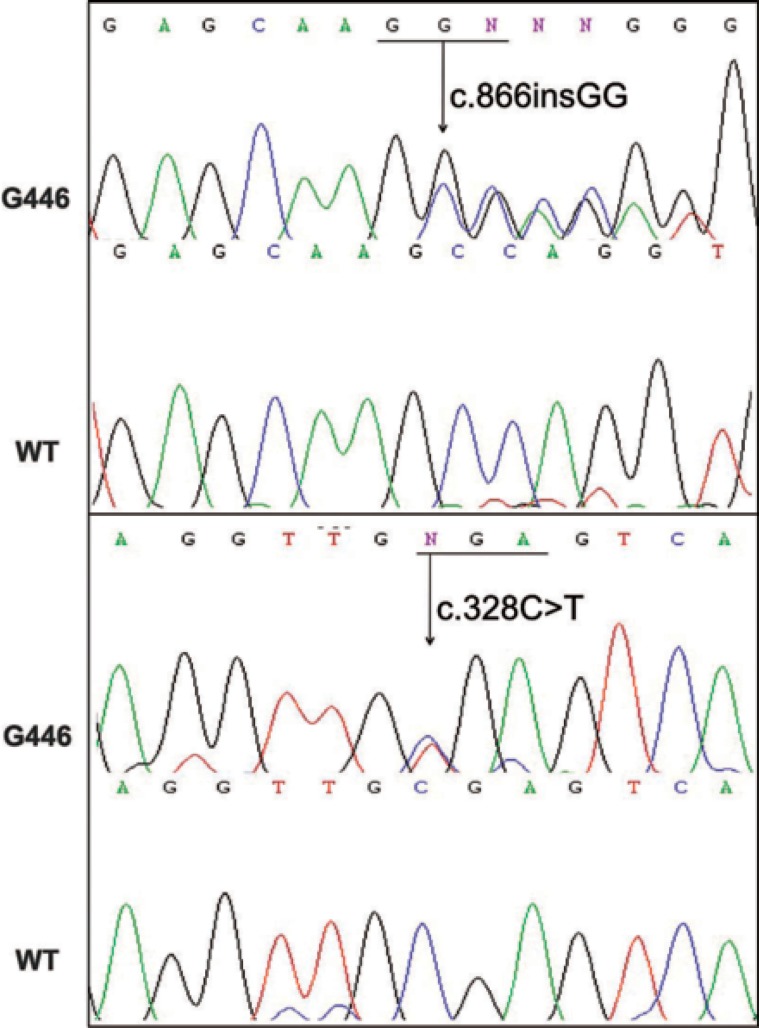

A 28-year-old woman from Porto Alegre reported that since childhood she had widespread skin pigmentary changes and photosensitivity, as well as fragility of the skin and mucous membranes. No other cases were reported in her family. Skin examination revealed marked atrophy of the skin on the back of the hands and feet, as well as a few scattered erosions/resolving blisters (Figure 1). There was extensive dyschromia on the limbs and trunk (Figure 2). We also noted a loss of dermatoglyphics on her fingers. Examination of her mouth showed erosive stomatitis. She also reported esophageal, vaginal and anal inflammation, leading to stricture formation, requiring surgical correction. A skin biopsy showed disruption of dermal collagen bundles and a focal reduction in elastic fibers (Figure 3). DNA was extracted from peripheral leucocytes and used to sequence the FERMT1 gene. Two heterozygous mutations were identified: the change c.328C>T results in the creation of a nonsense mutation, p.Arg110X and the insertion c.866insGG leads to a frameshift and a premature termination codon 7 amino acids downstream, p.Ala289GlufsX7 (Figure 4).

FIGURE 1.

Atrophy of the skin on the back of the hand (a) and foot (b)

FIGURE 2.

Dyschromia on the forearm (a) and trunk (b)

FIGURE 3.

Light microscopy with disruption of dermal collagen bundles (a) and focal reduction in elastic fibers (b) (Verhoeff Staining x100 and x 400)

FIGURE 4.

Sequencing of the FERMT1 gene with two heterozygous mutations

DISCUSSION

Kindler syndrome (OMIM 173650) was first described in 1954, associating congenital poikiloderma and hereditary EB, an atypical congenital skin disease.1 Nearly 50 years later, the molecular basis of KS was elucidated.1 The gene implicated in KS is FERMT1, which encodes FFH1, a focal contact protein that helps bind the actin cytoskeleton in basal keratinocytes to underlying extracellular matrix.2,5-7

In contrast to other forms of EB, in KS there is often a reduction in the number of blisters with increasing age as well as progression of skin atrophy and poikiloderma.2,8 Photosensitivity tends to be somewhat variable. Skin atrophy occurs early, usually before the age of 5, especially on the back of the hands and feet, as seen in our patient, and typically becomes widespread during adolescence. Mucosal involvement is common and erosions leading to scarring and stenoses, including gingivitis, periodontitis and urethral, anal, esophageal, laryngeal and vaginal stenosis. Severe colitis and constipation can also occur. Syndactyly, nail dystrophy, ectropion, corneal opacity, palmo-plantar keratoderma, pseudoainhum, leukokeratosis of the lips and genitals, xerostomy, dental caries, squamous cell carcinoma, hypohidrosis, phimosis and skeletal abnormalities, are listed as some of the protean manifestations reported.1,2 Typically, hematological or endocrine disorders are not a feature of KS, except in individuals with colitis who can develop iron - deficiency anemia.2

One curious feature in our patient was loss of dermatoglyphics, although this has been noted previously in KS.6 One of the most serious potential complications of KS is squamous cell carcinoma, which occurs in ~10% of cases. The alterations in skin pigment can also be associated with an increased incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer.

Skin histopathology in KS is typically not very informative: it shows hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy and pigmentary incontinence, which in essence are simply the features associated with poikiloderma.2 There is often a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis with fragmentation in the mid-dermis. A mild inflammatory infiltrate, predominantly consisting of macrophages and CD3 and CD4 lymphocytes, may also be present.6 Blistering is not evident in all biopsies and the plane of cleavage can be variable: intraepidermal, junctional or in the sub-lamina densa.1 Immuno mapping still cannot be used to establish the diagnosis.9

The diagnosis can be difficult to establish at birth (or indeed later in life) due to the considerable overlap with EB.2 Differential diagnoses typically include hereditary poikilodermas, simplex or dystrophic EB, xeroderma pigmentosum and dermopathia pigmentosa reticularis.1

Since the identification of the first pathogenic mutations in the FERMT1 gene, DNA sequencing has become the most useful and informative means of making a precise diagnosis.2 Nevertheless, FERMT1 mutations could not be detected in some clinical cases of KS, which might indicate genetic heterogeneity. For now, however, no additional genes have been identified.1

More than 50 mutations in FERMT1 have been identified, including in Brazilian patients.8 Martignago et al. described the occurrence of a recurrent FERMT1 mutation, c.676insC, in two different genetic backgrounds of Brazilian patients (some of whom were the descendents of Italian immigrants).10 Moreover, this Brazilian study also demonstrated widespread inter-familial and intra-familial variability in the clinical phenotypes of individuals with KS.9 For the mutations identified in our patient, one mutation (p.Arg110X) has been reported previously in unrelated individuals from other countries although the other (p.Ala289GlyfsX7) appears to be novel and unique to this individual/family. The consequences of these mutations could be similar to those previously reported, i.e. loss-of-function leading to low levels of the FERMT1 mRNA and FFH1 protein.

The management of KS is symptomatic. The use of emollients and sunscreens should be encouraged, since the skin is dry, itchy and often photosensitive.2 Regular clinical review is also recommended to screen for malignant or premalignant lesions, given the increased risk of skin cancer in KS.2 Regular dental reviews are necessary due to the high prevalence of erosive gingivitis and aggressive periodontitis that patients with KS may develop.2 In cases of esophageal, urethral or vaginal strictures, dilatation or surgical interventions may be necessary.2 Some patients with colitis symptoms may develop iron deficiency anemia and will need iron replacement.2

We have described a KS case that displays the typical features of this autosomal recessive genodermatosis. Clinicians should be aware of the potential disease complications and also how DNA sequencing can be very helpful in making an accurate diagnosis.

Footnotes

Work performed at the Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel) - Pelotas (RS), Brazil.

Conflict of interest: None

Financial funding: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Yazdanfar A, Hashemi B. Kindler syndrome: report of three cases in a family and a brief review. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai-Cheong JE, McGrath JA. Kindler Syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawamura D, Nakano H, Matsuzaki Y. Overview of epidermolysis bullosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:214–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Souza MAMA, Kimble RM, McMillan JR. Kindler syndrome pathogenesis and fermitin family homologue 1 (kindlin-1) function. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arita K, Wessagowit V, Inamadar AC, Palit A, Fassihi H, Lai-Cheong JE, et al. Unusual molecular findings in Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1252–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Has C, Burger B, Volz A, Kohlhase J, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Itin P. Mild Clinical Phenotype of Kindler syndrome associated with late diagnosis and skin cancer. Dermatology. 2010;221:309–312. doi: 10.1159/000320235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satter EK. A presumptive case of Kindler syndrome with a new clinical finding. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:646–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Has C, Castiglia D, del Rio M, Diez MG, Piccinni E, Kiritsi D, et al. Kindler syndrome:eextension of FERMT1 mutational spectrum and natural history. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:1204–1212. doi: 10.1002/humu.21576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira ZNP, Périgo AM, Fukumori MI, Aoki V. Immunological mapping in hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:856–861. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martignago BCF, Lai-Cheong JE, Liu L, McGrath JA, Cestari TF. Recurrent KIND1 (C20orf42) gene mutation, c.6676insC, in a Brazilian pedigree with Kindler syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1281–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]