Abstract

The present method of characterizing Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains involves serotyping or detection methods based on assessment of the presence or absence of genes thought to be markers of an organism's pathogenicity. It is unclear whether these assays detect all pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains since a clear correlation between the presence of a particular gene and the organism's pathogenicity has not yet been observed. We have described a proteomics-based method to distinguish individual V. parahaemolyticus strains on the basis of their protein profiles and identified a specific protein that is characteristic of the pandemic O3:K6 strain and its clonal derivatives. In the pandemic clone of V. parahaemolyticus, a histone-like DNA-binding protein, HU-α, has a C-terminal amino acid sequence different from those of other strains of V. parahaemolyticus. Upon further study, it was discovered that the gene encoding this protein has a 16-kbp insert at the 3′ terminus of the open reading frame for this protein. By using the protein sequence of the unique biomarker for the pandemic clone of V. parahaemolyticus, it was possible to rationally design specific PCR-based probes and assays that permit the rapid and precise identification of pandemic strains of V. parahaemolyticus.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a gram-negative bacterium that occurs naturally in marine waters and is commonly found in fish and shellfish dwelling in warm coastal waters. As an environmental organism, few strains of V. parahaemolyticus are capable of causing human disease. However, consumption of raw or improperly cooked shellfish and other seafood contaminated with a virulent strain of V. parahaemolyticus can cause chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, and in rare instances, death (5).

Until 1996, V. parahaemolyticus infections were characterized by sporadic cases caused by multiple, diverse serotypes. Since 1996, however, an increased incidence of gastroenteritis in many parts of Asia and the United States has been associated with V. parahaemolyticus serotype O3:K6 (3, 6, 22). Furthermore, other serotypes (O1:K25, O4:K68, and O1:K untypeable [O1:Kut]) which have been shown to be virtually identical to the O3:K6 serotype by a variety of molecular typing methods (4, 7, 20) and which have been postulated to be clonal derivatives of the O3:K6 isolates have also been implicated in pandemic V. parahaemolyticus infections.

Rapid methods for the characterization and differentiation of strains implicated in epidemics are needed to ensure the safety of seafood. The standard method for epidemiological investigations of V. parahaemolyticus outbreaks involves serotyping (11). Also, screening for the presence of the thermostable direct hemolysin (tdh) and the thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin (trh) genes, which are regarded as important virulence factors that are closely associated with the enteropathogenicity of the organism (13), has become a more commonly used method for identifying pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains. Molecular techniques, such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, ribotyping, arbitrarily primed PCR, group-specific PCR, and tdh sequence analysis, are routinely used to differentiate among V. parahaemolyticus isolates and confirm the close genetic relationships among the recently isolated V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains (32) and their clonal derivatives. As a consequence, molecular methodologies that target a phage-encoded open reading frame (ORF), referred to as ORF8, or a unique nucleotide sequence in the toxR gene of this recently emerging, pandemic O3:K6 clonal group have been suggested as a means for the specific identification of these organisms (9, 14, 18, 20, 21). Unfortunately, testing for these markers may not be a reliable means for identifying pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains, as was initially believed. The toxR marker has been found in nonpathogenic, tdh-negative O3:K6 strains (24), and ORF8 was not identified in several pathogenic, clinical O3:K6 isolates obtained between 1998 and 2000 (4). As a consequence, determination of the means by which species-specific markers can be identified remains an important facet of microbiology.

Most efforts to identify factors influencing virulence have focused on the genetic differences that exist between the pathogens of a bacterial species and the otherwise virtually isogenic, nonpathogenic counterparts (12, 26). Genes encode the proteins that function in the numerous cellular pathways utilized by the organism, and thus, a consequence of a change in the bacterial genome is often an altered protein expression profile. The difference between pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacterial strains may be reflected by the expression of new proteins, differences in the amounts of proteins expressed, protein sequence mutations, or the presence or absence of posttranslational modifications.

Both matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) have been widely touted as methods useful for the identification of microorganisms on the basis of their protein profiles (10, 16, 17, 27). Protein biomarkers from intact bacterial cells have been reported, and spectral fingerprints are believed to be useful for the identification of microorganisms or for distinguishing between different strains of bacteria (2, 8, 29, 31).

We have developed a new method for generating bacterial protein profiles from the LC/MS chromatograms of bacterial cell lysates (30). The method translates the chromatographic and multiply charged protein information into one comprehensive mass-versus-intensity spectrum. After the data are converted, a number of software tools can be used to compare bacterial protein profiles and monitor changes in protein expression that may be linked to pathogenicity. If significant changes in protein expression profiles can be identified, the proteins of interest are purified, sequenced, and examined for alterations in primary sequence composition and/or posttranslational modifications.

In an effort to identify a useful protein biomarker for the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain and its clonal derivatives responsible for producing epidemic and pandemic infections, this procedure was used to compare and distinguish between a pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain (VP47) and another distally related V. parahaemolyticus O4:K55 strain (strain BAC-98-3547). Analysis of the lysates from whole bacterial cells by LC/MS revealed differences in the masses of several proteins in each of the strains. Initially, it was unclear whether the protein compositions of the strains actually differed or if the VP47 strain simply contained proteins that had been modified. This work describes the effort that identified and sequenced a unique protein that has been determined to be characteristic of the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 pandemic clones. Furthermore, the effort culminated in the design of a PCR methodology that can be used individually or in combination with the LC/MS method to identify these organisms quickly and promote the overall safety of seafood commodities for public consumption.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The genotypic profiles for V. parahaemolyticus-associated determinants, as determined by PCR analysis of each strain, are also shown in Table 1. V. parahaemolyticus cell cultures were grown for 24 h on tryptic soy agar (Difco Laboratories, Sparks, Md.) supplemented with 2% NaCl. The cell isolates were suspended in 70% ethanol and stored at 4°C until needed.

TABLE 1.

V. parahaemolyticus strains used in this study

| Isolate | Origin | Source | Serotype | HU-α molecular mass (Da) | HU::insert | tdh | trh | V. parahaemo- lyticus toxR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KX-V225 | Japan | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| KX-V226 | Japan | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VP47 | Japan | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VPHY67 | Thailand | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VPHY145 | Thailand | Clinical | O4:K68 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VPHY123 | Thailand | Clinical | O1:Kut | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VPHY197 | Thailand | Clinical | O1:K41 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| VPHY191 | Thailand | Clinical | O1:K25 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AO-24491 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O1:K25 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AN-5034 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O4:K68 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AN-16000 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O1:Kut | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| U-5474 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O3:K6 (pre-1996) | 9,465 | − | + | − | + |

| AP-11243 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O1:Kut | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AN-2189 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O4:K68 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AP-14861 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AN-2416 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AP-9251 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AP-10866 | Bangladesh | Clinical | O1:K6 | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| AQ-4037 | Maldives | Clinical | O3:K6 (pre-1996) | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| CT 6636 | Connecticut | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| NY 3064 | New York | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| BAC-98-3483 | New York | Clinical | O4:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| BAC-98-3547 | New York | Clinical | O4:K55 | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| RI-03-90A | Rhode Island | Clinical | NT | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| RI-03-90B | Rhode Island | Clinical | NT | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| TX 2103 | Texas | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| TX 2062 | Texas | Clinical | O3:K6 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| AQ4750 | International traveler | Clinical | O1:K41 | 9,465 | − | + | − | + |

| KXV-755 | International traveler | Clinical | O1:K41 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| KXV-641 | International traveler | Clinical | O1:K25 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| KXV-6 | International traveler | Clinical | O1:K25 | 9,568 | + | + | − | + |

| DI-E3-031400 | Alabama | Oyster | NT | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| DI-A-6-020800 | Alabama | Oyster | O11:K61 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| DI-D12-031699 | Alabama | Oyster | O4:K9 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 47977 | Washington | Clinical | O4:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | − | + |

| 48291 | Washington | Clinical | O12:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 48262 | Washington | Clinical | O1:K56 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 901128 | Idaho | Clinical | O6 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 17802 | Japan | Clinical | O1 | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| SAK8 | Japan | Clinical | O4:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 10295 | Washington | Clinical | O1 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| NY477 | New York | Oyster | O4:K8 | 9,465 | − | + | − | + |

| M350A | Washington | Oyster | O5 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| AO-C2 | Washington | Oyster | O3 | 9,465 | − | − | − | + |

| AO-C3 | Washington | Clam | O3 | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

| AO-C6 | Washington | Clam | O3 | 9,465 | − | − | − | + |

| T3937 | Japan | Clinical | O4:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| T3979 | Japan | Clinical | O5:K15 | 9,465 | − | + | + | + |

| 8700 | Japan | Clinical | O4:K12 | 9,465 | − | + | − | + |

| CO5-1A | Washington | Oyster | O3 | 9,465 | − | − | + | + |

DNA isolation and toxR PCR analyses.

Genomic DNA was isolated from either bacterial cells from live cultures or bacterial cells previously suspended in 70% ethanol. Bacteria from approximately 2 ml of an overnight culture (or in ethanol) were centrifuged and resuspended in 250 μl of sterile, distilled H2O and boiled for 10 min. Afterwards, the preparations were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to pellet the cellular debris. The supernatant containing the DNA was collected and transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube for use in subsequent PCR analyses.

All strains were tested by PCR for the presence of the V. parahaemolyticus-specific toxRS genetic locus, as described by Kim et al. (15), in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 1× Taq buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 300 nM toxR primers, 150 mM 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA)-specific primers (forward primer, 5′-AAG AAG CAC CGG CTA ACT CC; reverse primer, 5′-CGC ATT TCA CCG CTA CAC C), ∼150 ng of DNA template (in 1 μl), and 2.5 U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). Following incubation for a single cycle at 95°C for 15 min, amplification was performed by 30 successive cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension incubation at 72°C for 30 s. Amplification was terminated by a single cycle of incubation at 72°C. Ten microliters of the reaction mixture was electrophoresed on a 1% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) agarose gel, and the gel was evaluated on a UV transilluminator. Lanes containing a 358-bp toxR product and the 205-bp 16S rDNA product were considered positive for V. parahaemolyticus. Strains that failed to generate the 358-bp toxR product but that did produce the 16S rDNA amplicon were not considered to be V. parahaemolyticus. Several non-V. parahaemolyticus strains were tested to evaluate the efficiency of this analysis (data not shown).

LC/MS experiments.

Proteins were extracted from bacterial cells with a 50:45:5 solution of acetonitrile (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, N.J.), high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade water (J. T. Baker), and formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.). The cells were first vortexed to form a slurry of cells. A total of 100 μl of this slurry was removed and centrifuged to a pellet, and the ethanol was removed. The cells were then mixed with 1 ml of the extraction solution. The microtubes containing the cells and extraction solution were placed in an ultrasonic water bath (Sonicor, Copiague, N.Y.) at room temperature for 30 min for gentle sonication in the extraction solvent. The cells were then centrifuged to a pellet, and the solution extract was removed. This solution was vacuum evaporated for 1 h with a Labconco (Kansas City, Mo.) Centrivap console. The volume of the remaining sample was approximately 500 μl.

For analytical separations, an Agilent (Palo Alto, Calif.) 1100 HPLC system fitted with an LC column (20 cm by 320 μm [inner diameter]) packed in-house with POROS 10 R2 packing (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) was used to separate the proteins of the whole-cell bacterial extract. The sample (2 μl) was injected onto the column, and the separation was carried out at a flow rate of 50 μl/min with a very shallow gradient (10 to 50% phase B in 50 min). Mobile phase A was 5% acetic acid in water, while mobile phase B was 5% acetic acid in acetonitrile.

The same HPLC system and solvents were used for preparatory separations. The column was changed, and the new column (10 cm by 1 mm [inner diameter]) was packed in-house with the same POROS 10 R2 packing. The injection volume was increased to 50 μl. The flow rate was also increased to 400 μl/min, with 100 μl reaching the mass spectrometer and the other 300 μl diverted to an Agilent 1100 fraction collector. The fraction collector was used to collect fractions at 1.0-min intervals. Monitoring by MS was maintained to ensure that there were no changes in the chromatography that would hinder the pooling of fractions from multiple runs and to facilitate determination of which fractions contained the desired proteins.

The fraction containing the protein of interest was evaporated to dryness and reconstituted in 50 μl of Rapigest anionic surfactant (Waters, Bedford, Mass.). The protein was incubated at 37°C with either 1 μmol of modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, Wis.) or endoprotease Asp-N of Pseudomonas fragi (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company) for 2 h for complete protein digestion.

A total of 10 μl of the protein digest was injected onto a Symmetry 300 (Waters) C18 column with dimensions of 150 by 0.320 mm (inner diameter). Chromatography was completed with the Agilent 1100 system with the same mobile phase and the same gradient used for the analytical separation, but with a flow rate of 20 μl/min.

MS and MS/MS experiments were performed on a Micromass (Beverly, Mass.) QTOF II mass spectrometer. Automated analysis of the full-scan (MS) data was performed with ProteinTrawler, custom software written for this purpose by BioAnalyte, Inc. (Portland, Maine). The function of this program is to automate data-processing subroutines within the data-processing program and to produce a combined time and intensity text output file. A detailed explanation of this program has been published elsewhere (30). Briefly, the program sums all data within a specified time interval; uses the MaxEnt 1 program to deconvolute the multiply charged ions; centers the result; performs a threshold selection; and reports the mass, intensity, and retention time of the protein in a text file. It continues this process across sequential portions of the chromatogram. All aspects of the subroutines, including retention times, mass windows, numbers of MaxEnt 1 program iterations, and number of spectra to combine can be controlled through the ProteinTrawler program.

Upon completion of the ProteinTrawler program, the text file contains a cumulative list of all the protein masses that were observed upon deconvolution of the individual summed spectra. This text file records the mass, intensity, and retention time. The retention time information is held in the text file, which the user can reference if a protein is singled out or deemed significant for further study, and thereby facilitates the isolation and purification process. It can also be used to verify that proteins of the same mass are actually two unrelated proteins, as indicated by their different retention times. A graphing program such as Grapher (version 3; Golden Software, Inc., Golden, Colo.) can read the file and display the data.

The PepSeq program of Micromass's ProteinLynx software package was used to analyze the sequence (MS/MS) data, while the ProteinInfo program of PROWL (http://65.219.84.5/service/prowl/proteininfo.html) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database were used for protein identification.

Cloning and sequencing of the BAC-98-3547 HU-α ORF.

The ORF of V. parahaemolyticus BAC-98-3547 HU-α, a histone-like DNA-binding protein, could not be amplified by PCR with primers specific for the HU-α ORFs of several Vibrio species, including V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolate VP47. Consequently, approximately 5 μg of genomic DNA from 0.5 ml of an overnight culture of BAC-98-3547 obtained with the EpiCentre MasterPure DNA system was restriction digested for 3 h at 37°C with 40 U of HindIII (in a 30-μl volume) and electrophoresed on a 1% TBE agarose gel. The DNA was transferred to a Nytran Supercharge nylon membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) for Southern blot analysis (25). A 245-bp digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe was prepared for use in the analysis with the Roche PCR DIG probe synthesis kit and primers specific to conserved regions within the HU-α ORF (forward primer, 5′-CCA ATT AAT CGA CTT TAT CGC AGA G; reverse primer, 5′-TCA GTG CTT TAC CTG CTA CGA ATG). Prior to amplification, the 50-μl reaction mixture was incubated at 95°C for 5 min. Amplification of the HU-α target was achieved with 35 successive cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and extension incubation at 72°C for 20 s. Following the reaction, a 1-μl aliquot of the labeling reaction mixture and a 1-μl aliquot of an unlabeled control reaction mixture were electrophoresed on a 1% TBE agarose gel to verify the presence of a 245-bp amplicon (unlabeled) and an amplicon that migrated slightly higher (DIG labeled), indicating that the procedure was successful. Probe hybridization and detection were performed as described by Weagant et al. (28). The results demonstrated that the HU-α ORF resided on an ∼4,300-bp HindIII restriction fragment (data not shown).

Cloning of the V. parahaemolyticus BAC-98-3547 HindIII fragment containing the HU-α ORF was facilitated by restriction digesting ∼10 μg of DNA for 3 h at 37°C and electrophoresing the reaction on a 1% TBE agarose gel. DNA ranging in size from 3 to 5 kb was recovered from the agarose gel and ligated into HindIII-digested pBluescript SK(−) (Strategene) in a 15-μl reaction mixture containing 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer and 5 U of T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen) that was incubated overnight at 15°C. The ligation reaction mixture was used as the template in a 50-μl PCR mixture that contained 1× Taq buffer, 3 mM MgCl2, a 400 μM concentration of each dNTP, concentrations of 300 nM (each) the forward HU-α-specific internal primer and the vector-specific universal T3 bacteriophage promoter primer, and 2.5 U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). Following enzyme activation by incubation at 95°C for 15 min and product amplification with 40 cycles, each of which consisted of incubations at 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 3 min, the resulting product was directly sequenced by using the forward HU-α primer of Amplicon Express (Pullman, Wash.) to determine the HU-α genetic sequence downstream of the 5′ primer binding site. Similarly, the sequence upstream of the reverse HU-α primer was obtained by the same strategy, in which the 3′ reverse HU-α primer was used in combination with the T3 bacteriophage promoter primer to generate the PCR amplicon that was sequenced with the 3′ reverse primer.

PCR analysis of V. parahaemolyticus strains for the HU-α ORF carrying the O3:K6 insertion mutation.

A reverse 3′ primer (5′-CTA GTA AGG AAG AAT TGA TTG TCA AAT AAT G) was designed that annealed specifically to the insertion sequence observed in the V. parahaemolyticus VP47 strain but that was not noted in the V. parahaemolyticus BAC-98-3547 strain to work in conjunction with a 5′ forward primer (5′-CGA TAA CCT ATG AGA AGG GAA ACC), which annealed immediately upstream of the HU-α ORF, to generate a 474-bp amplicon from templates with the HU::insertion genotype. The reactions were performed in a 50-μl volume containing 1× Taq buffer (Qiagen), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 300 nM (each) HU::insert primers, 100 nM 16S rDNA-specific primers (see above), ∼150 ng of template, and 2.5 U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). After enzyme activation, the templates were amplified for 30 consecutive cycles, each of which consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, primer annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and extension incubation at 72°C for 30 s. Ten microliters of each reaction mixture was electrophoresed on a 1% TBE agarose gel and visualized on a UV transilluminator. Those samples producing both the 474- and 205-bp amplification products were positive for the HU::insertion genotype, while those producing only the 205-bp product were not. The products from reactions producing neither amplification product were not evaluated.

RESULTS

toxR results.

The results of PCR analysis for the toxR gene were positive only for those strains that contained the gene. The results are shown in Table 1. No non-V. parahaemolyticus strains tested positive.

Protein analysis by MS.

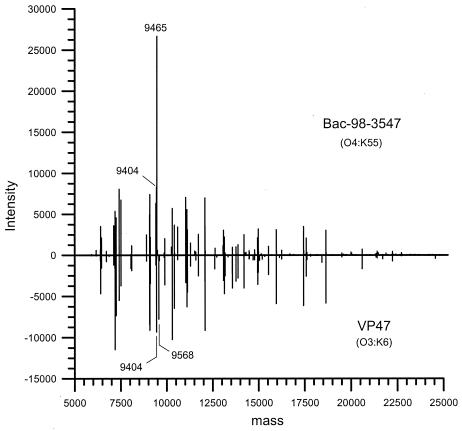

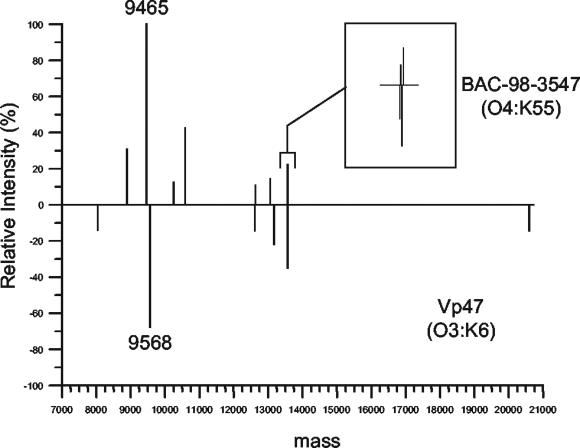

Differences in the protein compositions of two different V. parahaemolyticus strains were observed in the reconstructed mass-versus-intensity spectrum shown in Fig. 1. The protein profile shows that the protein fingerprints of the bacteria were reproducible, with few differences observed (Fig. 2). One consistent difference between many strains of V. parahaemolyticus was the presence of an abundant protein with a molecular mass of either 9,465 or 9,568 Da. These proteins never appeared together in the same strain. For example, the BAC-98-3547 strain of V. parahaemolyticus expresses a protein with a molecular mass of 9,465 Da, while the VP47 strain has a protein with a molecular mass that is 103 Da greater than that of the BAC-98-3547 protein. It was not clear whether the proteins were two completely different proteins or whether they were the same protein with a minor difference, such as an amino acid substitution or posttranslational modification. Regardless, these proteins appeared to be significant indicators of strain differences. Sequencing and identification of these proteins were performed to provide insight into whether they could be used as biomarkers to identify the new O3:K6 pandemic clone.

FIG. 1.

Single representative cellular protein spectrum for each of two V. parahaemolyticus strains. The majority of the proteins in the two strains are identical. Differences in the masses of the proteins of the O3:K6 strain and the O4:K55 strain were observed (molecular masses, 9,568 and 9,465 Da, respectively).

FIG. 2.

Representative protein profiles of the two bacterial strains were observed to differ at only 11 peaks. The inset plot shows that while some of the peaks differ by only 1 or 2 Da, they are discrete peaks.

The tryptic fragments of both the 9,568-Da protein and the 9,465-Da protein matched that of a DNA-binding protein found in both V. cholerae and V. proteolyticus. At the time of this analysis, there were no matches for V. parahaemolyticus, as that genome had not yet been completely sequenced. The genome of an O3:K6 strain of V. parahaemolyticus has since been published (19). All digestion fragments that were observed in our laboratory are listed in Table 2. It is noteworthy that the tryptic fragments that we used to identify the protein are highly conserved portions of the protein. Other tryptic fragments were identified and sequenced but matched a portion of the DNA-binding protein that is not conserved between the V. proteolyticus and V. cholerae species. It stands to reason that these amino acids are also different in V. parahaemolyticus, which in fact was proven correct when the genome sequence of a V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain was published (19). The amino acid sequence determined by tryptic digestion and LC/MS/MS is underlined below, and the sequences of these tryptic peptides were the same in both proteins of the two V. parahaemolyticus strains: MNKTQLIDFIAEKADLSKAQAKAALEATLEGVTGALKEGDQVQLIGFGTFKVNHRAARTGRNPKTGDEIQIAAANVPAFVAGKALKEACND.

TABLE 2.

Peptide sequences identified using LC/MS/MS

| Fragment and sequence | Observed m/z | Charge state | Molecular mass (Da)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Calculated | |||

| Tryptic fragment | ||||

| TQLIDFIAEK | 589.319 | +2 | 1,176.622 | 1,176.6390 |

| AALEATLEGVTGALK | 481.9218 | +3 | 1,442.748 | 1,442.7981 |

| AALEATLEGVTGALK | 722.382 | +2 | 1,442.748 | 1,442.7981 |

| AALEATLEGVTGALKEGDQVQLIGFGTFK | 741.657 | +4 | 2,962.597 | 2,962.5652 |

| AALEATLEGVTGALKEGDQVQLIGFGTFK | 988.524 | +3 | 2,962.549 | 2,962.5652 |

| EGDQVQLIGFGTFK | 769.884 | +2 | 1,537.752 | 1,537.7777 |

| TGDEIQIAAANTPAFVAGK | 624.659 | +3 | 1,870.994 | 1,870.9789 |

| TGDEIQIAAANTPAFVAGK | 936.505 | +2 | 1,870.994 | 1,870.9789 |

| Asp-N fragment | ||||

| DEIQIAAANTPAFVAGKALKESVN | 819.216 | +3 | 2,454.625 | 2,454.312 |

| PAFVAGKALKESVN | 715.903 | +2 | 1,429.847 | 1,429.793 |

The molecular mass of this protein sequence of DNA-binding protein HU-α from an O3:K6 strain of V. parahaemolyticus is 9,567.9 Da, the same mass observed by full-scan MS of the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain. Therefore, it is evident that the difference between the sequences of the proteins of the two V. parahaemolyticus strains is not due to a posttranslational modification but, rather, is due to a sequence mutation. Two different approaches were taken to determine the differences in the sequences: alternative enzymatic cleavage and genome sequencing.

Asp-N was chosen as an alternative digestion reagent since it cleaves on the N-terminal side of aspartic acid. In this case, the problem with using trypsin is that it cleaves at arginine and lysine residues; and upon complete digestion of the protein, some of the tryptic fragments were too small to be analyzed by LC/MS/MS. The regions of the protein (not underlined above) that could not be sequenced by trypsin digestion and LC/MS/MS were laden with arginine and lysine residues. Upon Asp-N digestion, followed by LC/MS/MS analysis, it was determined that the O4:K55 strain had an HU-α DNA-binding protein with a different carboxyl terminus. Instead of having a carboxyl terminus like that of the O3:K6 strain, it had the carboxyl terminus of the protein from V. vulnificus (Table 3), while the remainder of the protein was identical to that of the O3:K6 strain. Therefore, the protein of the O4:K55 strain has a molecular mass of 9,464.8 Da, and the amino acid sequence shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Protein sequence of DNA-binding protein HU-α from several Vibrio species

| Species | GenBank accession no. | Protein sequence at the following positions:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 21 | 26 | 31 | 36 | 41 | 46 | 51 | 56 | 61 | 66 | 71 | 76 | 81 | 86 91 | ||

| V. proteolyticus | P2808D | MNKTQ | LIDFI | AEKAD | LSKAQ | AKAAL | EATLD | GVTDA | LKEGD | QVQLI | GFGTF | KVNHR | AARTG | RNPKT | GAEIQ | IAAAN | VPAFV | AGKAL | KDAVK |

| V. cholerae | NP_229929 | MNKTQ | LIDFI | AEKAD | LTKVQ | AKAAL | EATLG | AVEGA | LKDGD | QVQLI | GFGTF | KVNHR | SARTG | RNPKT | GEEIK | IAAAN | VPAFV | AGKAL | KDAIK |

| V. vulnificus | NP_760155 | MNKTQ | LIDFI | AEKAD | LSKAQ | AKAAL | EATLN | GVTDA | LKEGD | QVQLI | GFGTF | KVNHR | AARTG | RNPKT | GDEIQ | IAAAN | VPAFV | AGKAL | KESVN |

| V. parahaemolyticus (O3:K6) | NP_799290 | MNKTQ | LIDFI | AEKAD | LSKAQ | AKAAL | EATLE | GVTGA | LKEGD | QVQLI | GFGTF | KVNHR | AARTG | RNPKT | GDEIQ | IAAAN | VPAFV | AGKAL | KEACND |

| V. parahaemolyticus (O4:K55) | NP_760155 | MNKTQ | LIDFI | AEKAD | LSKAQ | AKAAL | EATLE | GVTGA | LKEGD | QVQLI | GFGTF | KVNHR | AARTG | RNPKT | GDEIQ | IAAAN | VPAFV | AGKAL | KESVN |

Southern blot analysis of the BAC-98-3547 V. parahaemolyticus strain.

Amplification of the HU-α ORF with the primers that were generated to anneal to conserved regions within the ORF was found to produce an amplicon that was 245 bp in length. The amplicon was labeled with DIG and was used as the HU-α-specific probe in the Southern blot analysis. Following the analysis, the results demonstrated that the BAC-98-3547 HU-α ORF resided on an ∼4,300-bp HindIII restriction fragment (data not shown) that was suitable for cloning into pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene) for sequence analysis. Following ligation of the HindIII-digested genomic DNA into pBluescript SK(−), the ligation products were initially used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α so that the recombinant plasmids could be isolated and sequenced. Several attempts to isolate transformants carrying the appropriate plasmid construct failed, suggesting either that the ligation protocol had not generated the desired construct or that the ∼4.3-kb DNA fragment on which the HU-α ORF resided in some manner inhibited or restricted E. coli growth or viability when the fragment was carried on the high-copy-number pBluescript SK(−) cloning vector. To ascertain whether either of these was the case, the ligation products themselves were used as the templates for PCR amplification to generate DNA that could be directly sequenced. Product selectivity for this strategy was ensured by use of a primer combination that contained one primer that annealed to the HU-α target sequence and a complementary primer that annealed to the plasmid vector. Amplicons could be derived by this strategy only if the desired DNA had been ligated into the plasmid. Since this strategy did produce amplicons, indicating the presence of the appropriate plasmid construct, it appears that the construct possesses properties that are not conducive to either efficient transformation by electroporation or cell viability.

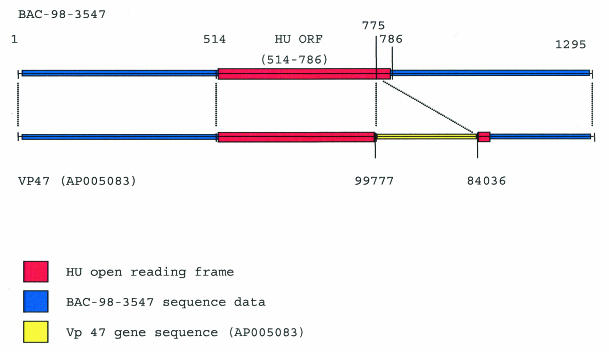

Sequence analysis of V. parahaemolyticus BAC-98-3547 enabled the compilation of 1,295 nucleotides that contained the HU-α ORF of this strain. GAP analysis of BAC-98-3547 and VP47 with Genetics Computer Group software indicated 100% sequence homology between the two strains of the 250 nucleotides immediately upstream of the ORF. Furthermore, this level of homology was observed to persist throughout the ORF to position +261, at which point there was a distinct departure from the sequence reported in GenBank for the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strain (GenBank accession no. AP005083). Interestingly, a BLAST analysis at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website with the 3′ sequence obtained from BAC-98-3547 downstream of the breakpoint indicated that this sequence was present in the O3:K6 strain but was separated from the 5′ portion of the HU-α ORF by an approximately 16-kb DNA insertion. The introduction of this insertion altered the ORF such that the amino acid composition of HU-α of the O3:K6 strain differed from that of the protein of strain BAC-98-3547 at two of three of the terminal residues and the ORF of the HU-α of O3:K6 strain was a single amino acid longer than that of the HU-α of BAC-98-3547 protein (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Insertion sequence of the O3:K6 strain is located in the ORF of DNA-binding protein HU-α. The figure is not drawn to scale.

PCR detection of the HU::insertion sequence.

On the basis of the new sequence data, a PCR analysis for the detection of the insertion mutation was designed and used to assay the other V. parahaemolyticus strains used in this study (Table 1). In conjunction with an LC/MS analysis, the PCR analysis of those strains demonstrated that the insert was found in all strains that expressed the HU-α protein with a molecular mass of 9,568 Da. Moreover, these findings were observed only in the O3:K6 clonal group of strains consisting of not only the O3:K6 serotype but also the O4:K68, O1:K25, and O1:Kut serotypes. Furthermore, evidence collected thus far suggests that this particular marker is restricted to this particular clonal lineage and could be used to identify other strains belonging to this group.

DISCUSSION

Until recently, the predominance of a single serovar of V. parahaemolyticus as the causative agent of widespread disease had not been reported. However, in 1989, a V. parahaemolyticus O4:K12 strain was reported to be the causative agent of infections on the western coasts of both Mexico and the United States (1). Furthermore, in 1995, the emergence of a V. parahamolyticus O3:K6 strain that was the causative agent of the pandemic disease that spread to seven Asian countries and the United States was reported (20). As this trend is likely to continue, the need to design methodologies by which the strains might be readily detected has become a major focus of the microbiology community.

In the case of the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 serogroup and its clonally related serovariants, V. parahaemolyticus O4:K68, V. parahaemolyticus O1:K25, and V. parahaemolyticus O1:Kut, several molecular methodologies, including arbitrarily primed PCR and target-specific PCR, by which this group of strains can be readily distinguished from other unrelated strains have been designed. Taking advantage of determinants that are present in one strain but that are not found in another is one means by which such methods can be designed. Such methods include screening for the presence of the tdh gene, which is observed in the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 clonal group but which is not noted in other environmental strains, or determination of allelic differences in genes shared by both pathogenic and nonpathogenic isolates, as is the case for the group-specific toxR PCR methodology described by Matsumoto et al. (20). Several reports have demonstrated that these approaches are not reliable methods for identification of the pandemic strains (23, 24).

Often, it is not readily apparent what differences exist between closely related strains that may serve as suitable markers that can be exploited to design strain-specific detection protocols. Analysis of individual strain protein profiles can provide information regarding the protein expression differences that exist between strains that can be subjected to rationally designed nucleic acid-based detection methods to differentiate one strain from others. As described in this work, we have used a previously described LC/MS method that can identify differences in protein expression profiles or, as was the case with the HU-α protein targeted in our study, that can detect subtle differences in the amino acid compositions of proteins that are expressed by two related strains. Additionally, this method has the added advantage of targeting determinants that are not necessarily related to or required for pathogenicity, clearly broadening the range of targets that could be considered when determining the best means for detecting specific organisms. Here, we have shown that the HU-α protein is sufficiently unique such that this particular allelic variant is specific for the V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 clonal group responsible for pandemic disease. Moreover, we have shown that the protein sequence information obtained from the MS experiment can be used as part of a rational approach to the design of specific molecular detection methods. The PCR detection protocol designed as a result of this approach is based on sequence information derived from the HU-α ORFs of V. parahaemolyticus BAC-98-3547 and V. parahaemolyticus VP47.

Interestingly, our effort to characterize the HU-α proteins from these two V. parahaemolyticus strains revealed the presence of a large (∼16-kbp) insertion sequence at the 3′ terminus of the VP47 HU-α ORF. This insertion sequence results in a modification of the last four amino acids of the C terminus of the transcribed protein. The effect of this insertion sequence on the HU-α protein's activity and whether the insertion sequence has any relation to a change in pathogenicity are unknown. Nevertheless, we have demonstrated that this insertion sequence and its corresponding modification of the HU-α protein sequence are unique to O3:K6, O1:K25, O4:K68, and O1:Kut strains, all of which possess the potential to initiate the spread of pandemic disease.

Since it is likely that the trend for serospecific organisms to be the agents responsible for pandemic illness will continue, there is a need for methodologies that can determine the subtle differences that exist between very closely related strains. Although only the HU-α protein was characterized in this study, LC/MS detected other protein expression differences that could have been singled out for further study. As such, it is apparent that the use of this protocol could provide numerous alternate molecular targets that might be exploited to design the means by which to discern a single strain from other closely related organisms. The capability of the method to identify specific expressed protein targets and the ease with which specific protein sequence information can be adapted to molecular detection methods combine to offer a powerful new tool for differentiating and detecting microorganisms important to food safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitsuaki Nishibuchi of Kyoto University, G. B. Nair of the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, and Ben Tall of the Food and Drug Administration for kindly providing us with parts of their culture collections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, S. L., C. Powers, C. A. Kaysner, Y. Takeda, M Ishibashi, S. W. Joseph, and J. M. Janda. 1989. Emergence of a restricted bioserovar of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as the predominant cause of Vibrio-associated gastroenteritis on the West Coast of the United States and Mexico. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2891-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold, R. J., and J. P. Reilly. 1998. Fingerprint matching of E. coli strains with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry of whole cells using a modified correlation approach. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 12:630-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bag, P. K., S. Nandi, R. K. Bhadra, T. Ramamurthy, S. K. Bhattacharya, M. Nishibuchi, T. Hamagata, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 1999. Clonal diversity among recently emerged strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 associated with pandemic spread. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2354-2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhuiyan, N. A., M. Ansaruzzaman, M. Kamruzzaman, K. Alam, N. R. Chowdhury, M. Nishibuchi, S. M. Faruque, D. A. Sack, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2002. Prevalence of the pandemic genotype of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and significance of its distribution across different serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:284-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blake, P. A., R. E. Weaver, and D. G. Hollis. 1980. Diseases of humans (other than cholera) caused by vibrios. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 34:341-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiou, C.-S., S.-Y. Hsu, S.-I. Chiu, T.-K. Wang, and C.-S. Chao. 2000. Vibrio parahaemolyticus serovar O3:K6 as cause of unusually high incidence of food-borne disease outbreaks in Taiwan from 1996 to 1999. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4621-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury, N. R., S. Chakraborty, T. Ramamurthy, M. Nishibuchi, S. Yamasaki, Y. Takeda, and G. B. Nair. 2000. Molecular evidence of clonal Vibrio parahaemolyticus pandemic strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:631-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demirev, P. A., Y.-P. Ho, V. Ryzhov, and C. Fenselau. 1999. Microorganism identification by mass spectrometry and protein database searches Anal. Chem. 71:32-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiRita, V. J. 1992. Co-ordinate expression of virulence genes by toxR in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 6:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenselau, C., and P. A. Demirev. 2001. Characterization of intact microorganisms by MALDI mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 20:157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food and Drug Administration. January 2001, posting date. Bacteriological analytical manual. [Online.] Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Md. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼ebam/bam-9.html.

- 12.Groisman, E. A. (ed.). 2001. Principles of bacterial pathogenesis. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 13.Honda, T., and T. Iida. 1993. The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct haemolysin and related haemolysins. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 4:106-113. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida, T., A. Hattori, K. Tagomori, R. Nasu, R. Naim, and T. Honda. 2001. Filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:477-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, Y. B., J. Okuda, C. Matsumoto, N. Takahashi, S. Hashimoto, and M. Nishibuchi. 1999. Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains at the species level by PCR targeted to the toxR gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1173-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnamurthy, T., M. T. Davis, D. C. Stahl, and T. D. Lee. 1999. Liquid chromatography/microspray mass spectrometry for bacterial investigations. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 13:39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lay, J. O., Jr. 2001. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of bacteria. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 20:172-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin, Z., K. Kumagai, K. Baba, J. J. Mekalanos, and M. Nishibuchi. 1993. Vibrio parahaemolyticus has a homolog of the Vibrio cholerae toxRS operon that mediates environmentally induced regulation of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene. J. Bacteriol. 175:3844-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makino, K, K. Oshima, K. Kurokawa, K. Yokoyama, T. Uda, K. Tagomori, Y. Iijima, M. Najima, M. Nakano, A. Yamashita, Y. Kubota, S. Kimura, and T. Yasunaga. 2003. Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae. Lancet 361:743-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto, C., J. Okuda, M. Ishibashi, M. Iwanaga, P. Garg, T. Ramamurthy, H.-C. Wong, A. Depaola, Y. B. Kim, M. J. Albert, and M. Nishibuchi. 2000. Pandemic spread of an O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and emergence of related strains evidenced by arbitrarily primed pcr and toxRS sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:578-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasu, H., T. Iida, T. Sugahara, Y. Yamaichi, K.-S. Park, K. Yokoyama, K. Makino, H. Shinagawa, and T. Honda. 2000. A filamentous phage associated with recent pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2156-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuda, J., M. Ishibashi, E. Hayakawa, T. Nishino, Y. Takeda, A. K. Mukhopadhyay, S. Garg, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. B. Nair, and M. Nishibuchi. 1997. Emergence of a unique O3:K6 clone of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Calcutta, India, and isolation of strains from the same clonal group from Southeast Asian travelers arriving in Japan J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:3150-3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okura, M., R. Osawa, A. Iguchi, E. Arakawa, J. Terajima, and H. Watanabe. 2003. Genotypic analyses of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and development of a pandemic group-specific multiplex PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4676-4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osawa, R., A. Iguchi, E. Arakawa, and H. Watanabe. 2002. Genotyping of pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 still open to question. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2708-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Slyers, A. A., and D. D. Whitt. 1994. Bacterial pathogenesis: a molecular approach. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 27.Wang, Z., K. Dunlop, S. R. Long, and L. Li. 2002. Mass spectrometric methods for generation of protein mass database used for bacterial identification. Anal. Chem. 74:3174-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weagant, S. D., J. A. Jagow, K. C. J. Nneman, W. E. Hill, and C. J. Omjecinski. 1998. Digoxigenin labelled PCR amplicon probes for the detection and identification of enteropathogenic Yersinia and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from foods, p. 1-18. FDA laboratory information bulletin 4144. Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Md.

- 29.Welham, K. J., M. A. Domin, D. E. Scannell, E. Cohen, and D. S. Ashton. 1998. The characterization of micro-organisms by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 12:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams, T. L., P. Leopold, and S. Musser. 2002. Automated postprocessing of electrospray LC/MS data for profiling protein expression in bacteria. Anal. Chem. 74:5807-5813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang, F., G. A. Anderson, T. D. Veenstra, M. S. Lipton, and R. D. Smith. 2000. Characterization of microorganisms and biomarker development from global ESI-MS/MS analyses of cell lysates. Anal. Chem. 72:2475-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung, P. S. M., M. C. Hayes, A. DePaolo, C. A. Kaysner, L. Kornstein, and K. J. Boor. 2002. Comparative phenotypic, molecular, and virulence characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2901-2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]