Significance

In a unique memory-distortion study with people with extraordinary memory ability, individuals with highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM) were as susceptible as controls to false memory. The findings suggest that HSAM individuals reconstruct their memories using associative grouping, as demonstrated by a word-list task, and by incorporating postevent information, as shown in misinformation tasks. The findings also suggest that the reconstructive memory mechanisms that produce memory distortions are basic and widespread in humans, and it may be unlikely that anyone is immune. The assumption that no one is immune from false memories has important implications in the legal and clinical psychology fields, where contamination of memory has had particularly important consequences in the past.

Keywords: hyperthymesia, DRM, suggestion, crashing memories

Abstract

The recent identification of highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM) raised the possibility that there may be individuals who are immune to memory distortions. We measured HSAM participants’ and age- and sex-matched controls’ susceptibility to false memories using several research paradigms. HSAM participants and controls were both susceptible to false recognition of nonpresented critical lure words in an associative word-list task. In a misinformation task, HSAM participants showed higher overall false memory compared with that of controls for details in a photographic slideshow. HSAM participants were equally as likely as controls to mistakenly report they had seen nonexistent footage of a plane crash. Finding false memories in a superior-memory group suggests that malleable reconstructive mechanisms may be fundamental to episodic remembering. Paradoxically, HSAM individuals may retrieve abundant and accurate autobiographical memories using fallible reconstructive processes.

Research on memory distortion suggests that episodic memory often involves a flawed reconstructive process (1–3). Several false-memory paradigms developed in recent decades have demonstrated this. For example, in the Deese-Roediger and McDermott (DRM) (4, 5) paradigm, people falsely remember words not actually presented in a related list of words. In the misinformation paradigm, the content of a person’s memory can be changed after they are exposed to misleading postevent information (2, 6, 7). In the nonexistent news-footage paradigm (also known as the “crashing memory” paradigm), people sometimes recall witnessing footage of news events for which no footage actually exists (8, 9). People can even remember events following an imagination exercise that inflates their certainty about events that they only imagined but did not actually experience (10). Even memory for our past emotions seems to be reconstructed and prone to error (11). So far, memory distortions have been investigated in subjects who have typical memory ability [children (12), adults (7), older adults (13)], but not with people with unusually strong memory ability. Memory-distortion phenomena have been explained by theoretical models that state that memory is reconstructed from traces at retrieval (1, 3, 14), is not reproduced from a permanent recording (15), and is prone to errors caused by source confusion (16) and association (17, 18). These studies and theoretical models paint a picture of human memory as malleable and prone to errors.

However, a small number of individuals who have recently been identified appear to be uniquely gifted in their ability to accurately remember even trivial details from their distant past (19–21). Highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM; also known as hyperthymesia) individuals can remember the day of the week a date fell on and details of what happened that day from every day of their life since mid-childhood. For details that can be verified, HSAM individuals are correct 97% of the time (20). For example, when one individual was asked what happened on October 19, 1987, she immediately responded with, “It was a Monday. That was the day of the big stock market crash and the cellist Jacqueline du Pré died that day.” HSAM individuals can remember what happened on a day a decade ago better than most people can remember a day a month ago. In some ways, these abilities seem to be at odds with what we know about the reconstructive, unreliable, and malleable processes underlying memory in people with typical memory.

HSAM abilities are distinct from previously described superior-memory individuals (22–25) who typically rely upon practiced mnemonics to remember unusually long lists of domain-specific data, yet remain average in their ability to retrieve autobiographical information. In contrast, HSAM individuals seem not to be superior learners, exhibiting average scores on typical laboratory memory tasks that are unrelated to autobiographical memory. Furthermore, HSAM individuals recall their past in rich detail and in a fashion that seems automatic and unaided by explicit mnemonic techniques or rote practice. It is puzzling that not all HSAM individuals report keeping diaries, routinely refreshing information (e.g., “what did I do on this day last year?”), or categorizing and cataloging their experiences on certain dates in their minds. The sheer amount of the personal experiences that they can recall fluidly seems highly unusual, and on objective measures of autobiographical memory the statistics are astounding. For example, on the very challenging 10 Date Quiz (see below), the mean score for HSAM participants is 25.5 SDs above the mean score for control participants (Cohen’s d). Structural MRI brain scans of people with HSAM have shown morphological differences in areas, such as the temporal gyri, that have been previously described as contributing to autobiographical memory (20). These areas were different in size and shape compared with age- and sex-matched controls, but conclusions have yet to be made as to if these differences are a result of nature, nurture, or both.

Here, we tested HSAM individuals’ susceptibility to memory distortion in the DRM, misinformation, nonexistent news footage, imagination inflation, and memory for emotion paradigms (see SI Materials and Methods and Figs. 1–3 for materials and procedural details). We recruited 20 HSAM participants and 38 age- and sex-matched controls. Seven of these 20 HSAM participants had previously been identified as HSAM individuals in prior published studies (19, 20) and 13 are new to the literature. HSAM participants were identified using a 30-question Public Events Quiz (PEQ) and a 10 Date Quiz (20). These tests are exceedingly difficult for control participants with normal memory. The PEQ consisted of 15 questions that asked participants to give the date of a well-known public event, and 15 questions that gave them a date and asked them to report a significant public event. The 10 Date Quiz consisted of 10 randomly generated dates for which participants were to give the day of the week that they fell on, a verifiable event within a month’s time of them, and a description of a personal autobiographical event that occurred on each of the dates. HSAM participants showed unusually high scores on both measures, compared with controls (SI Materials and Methods).

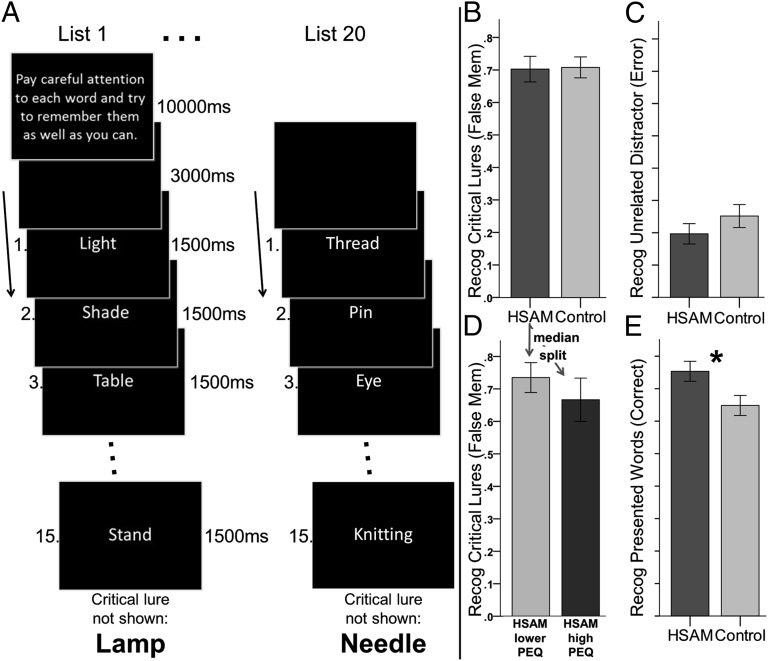

Fig. 1.

The DRM false-memory associative word list: a sample of materials and the main results. (A) The materials consisted of 20 lists, each 15 words long. Each word in a given list is related to a critical lure that the participants never actually saw. (B) The main result showed both HSAM individuals and controls falsely recognized a similarly high proportion of critical lures (MHSAM = 14.1; MControl = 14.2 of 20). The y axis indicates the mean proportion. (C) Both groups indicated seeing unrelated distractor words at the same proportion as one another, far less often than they endorsed seeing the critical lure words. (D) HSAM participants with the highest autobiographical memory ability (highest scores on the PEQ) were not significantly less susceptible to falsely endorsing critical lure words than HSAM participants who performed in the low range. (E) HSAM individuals outperformed controls on correctly recognized items that were presented earlier (hit rate), *P = 0.035. Error bars represent SEs.

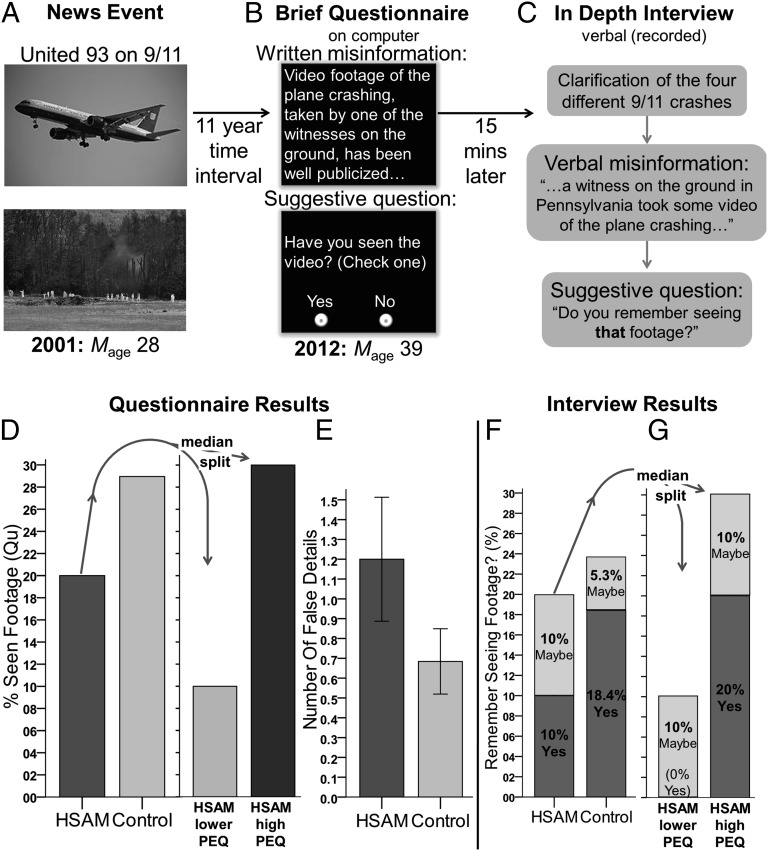

Fig. 3.

Materials and results of the nonexistent news-footage paradigm. (A) The target news event is the crash of United 93 in Pennsylvania. (B) The computer questionnaire stated that footage of the actual crash exists and asked participants to check whether they have seen the footage. (C) Later an in-depth interview carefully explained what we were asking about, and asked them if they had seen that footage. (D) In the computer questionnaire, 20% of HSAM individuals and 29% of controls indicated they had seen the footage. A median split of HSAM participants on the PEQ revealed 30% with higher PEQ scores indicated “yes” they had seen the footage; only 10% with lower PEQ scores did so. (E) The number of false details (of a possible four) indicated HSAM individuals were not statistically significantly higher than controls (P = 0.11). (F) In the interview, 10% of HSAM participants and 18% of the controls said yes they had seen the footage, and (G) a median split revealed that the highest-scoring HSAM individuals on the PEQ were no less susceptible than those HSAM participants lower on the PEQ. Error bars represent SEs.

Are people with HSAM abilities vulnerable to the same kinds of distortions and errors that others are, or do their abilities protect them in some way from suggestive influences? The answer to this question will help elucidate both the workings of HSAM and the nature of human memory more generally. If each memory-distortion paradigm produces false memory in a group with superior memory (as well as average-memory individuals, as shown in past research), perhaps the malleable reconstructive memory system is a fundamental part of human episodic memory. If we find HSAM individuals are only susceptible to some distortions, but not the semiautobiographical ones (nonexistent news footage, imagination, and memory for emotion), it suggests they retrieve memories in the autobiographical domain differently than the rest of the population. If HSAM participants show no memory distortions in any paradigm, such evidence would question the view that malleable, reconstructive, and fallible memory is in fact characteristic of all groups of people.

Results

To investigate the relationship between HSAM ability and memory distortion susceptibility, we first compared HSAM individuals to age- and sex-matched controls on a range of memory-distortion tasks. We then performed a median split on HSAM participants, comparing the 10 who scored above the HSAM median on the PEQ (one of the objective measures of autobiographical memory ability), to the 10 who scored below that median (for a median split analysis on the 10 Dates Quiz, see Fig. S1).

Fig. 1 shows the DRM word-list false-memory task. There was no significant difference between false-memory rates (recognition of critical lures: words not presented earlier, but related to presented words) of HSAM individuals (M = 70.3%, SD = 17.1%) and controls [M = 70.8%, SD = 19.9%; t(55) = −0.10, P = 0.922] (Fig. 1B). HSAM participants and controls incorrectly indicated they had seen an average of 14 of the 20 critical lures (HSAM range 8–20). In addition, there was no reliable difference in false-memory rate for HSAM individuals scoring low and high in the PEQ measure of autobiographical memory ability (Fig. 1D) [t(17) = 0.86, P = 0.403]. There were also no significant differences in error rates of recognizing unrelated distractor words that were neither presented earlier nor related to presented words (Fig. 1C) (HSAM participants 19.7%, controls 25.2%, P = 0.323; percentages in keeping with past DRM research). However, we found that HSAM individuals correctly recognized significantly more presented words (M = 76.6%, SD = 14.2%) than controls [M = 64.8%, SD = 19.0%), t(55) = 2.16, P = 0.035]. A signal detection analysis revealed HSAM participants were better at discriminating presented words from critical lures than controls, but no better at discriminating unrelated distractors from presented words (Fig. S2).

We next compared HSAM individuals to controls on their false-recognition rates of the five most emotionally arousing critical lure words, and on the five least arousing critical lures. This analysis revealed no significant differences between HSAM participants and controls [emotional: t(55) = −0.39, P = 0.699; neutral: t(55) = 0.17, P = 0.870].

On the misinformation task (Fig. 2), a statistically significant misinformation effect was observed in both groups. Exposure to misinformation caused participants to incorporate that information into their memory for the original stimulus at significantly higher rates than those who were not exposed (Fig. S3).

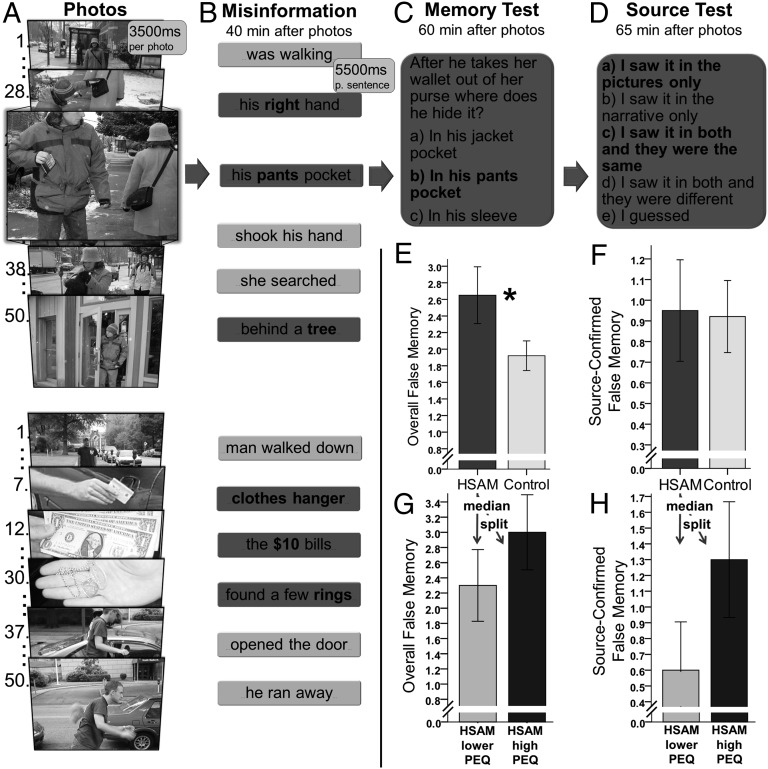

Fig. 2.

The misinformation paradigm. (A) Participants saw two events that unfolded in slideshows consisting of 50 photographs each. The first event featured a man stealing a wallet from a woman while pretending to help, and the second event showed a man breaking into a car with a credit card and stealing $1 bills and necklaces. (B) Later, participants read two narratives consisting of 50 sentences each, with six items of misinformation surreptitiously placed in among the 94 true sentences. (C) In the memory test, picking the misinformation consistent response is counted as an OFM. (D) In the source test, if one also indicates it was seen in the photos it is counted as a SCFM. The y axis gives the mean number of false memories. (E) HSAM participants had significantly higher OFM than controls and (F) about the same SCFM. There were no statistically significant differences on either OFM (G) or SCFM (H) between those HSAM individuals who scored highest on the PEQ and HSAM participants who had lower PEQ scores. Time intervals between A, B, C, and D are approximate. Error bars represent SEs.

We quantified the misinformation false memories by two metrics. Consistent with prior research (26), overall false memories (OFM) consisted of trials in which the participant chose the misinformation version during the memory test (e.g., pants pocket) (Fig. 2C). Source-confirmed false memories (SCFM) consisted of trials in which the participant further confirmed during the source test that he or she explicitly remembered seeing the image in the original photographic slideshow (Fig. 2D). Contrary to being immune from false memories on this test (Fig. 2E), HSAM participants (M = 2.65, SD = 1.53) had significantly more OFM than controls [M = 1.92, SD = 1.10, t(56) = 2.09, P = 0.041]. There was no reliable difference in the OFM score between those HSAM individuals with the highest autobiographical ability (PEQ) and the other HSAM participants (Fig. 2G) [marginal P value: t(18) = −1.74, P = 0.098]. Similarly, HSAM participants and controls showed remarkably similar SCFM scores (Fig. 2F) [t(56) = 0.19, P = 0.848] and there was no reliable evidence for a difference between the two sets of HSAM participants (Fig. 2H) [t(18) = −1.47, P = 0.160].

Taken together, these results indicate that the HSAM group exhibited false memories in the misinformation paradigm. The HSAM individuals with the best autobiographical memory were just as susceptible, if not more, to developing false memories, compared with HSAM participants with lower scores on the PEQ.

Next, in the nonexistent news-footage paradigm, we examined the tendency of HSAM participants and controls to report having seen the nonexistent plane crash footage in the computer questionnaire (Fig. 3 and SI Materials and Methods). Fig. 3D shows that 20% of HSAM individuals reported that they had seen the footage and a similar 29% of controls reported that they had seen it (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.541). There were also no differences in the number of false details remembered from the footage (Fig. 3E) between HSAM participants (M = 1.20, SD = 1.40) and controls [M = 0.68, SD = 1.02; t(56) = 1.61, P = 0.113]. These results, when combined, suggest comparable susceptibility to false memories in the nonexistent news-footage paradigm.

The nonexistent news-footage interview provides a more conservative measure of false memory than the computer questionnaire. Even in these interviews, we found both the HSAM group (Fig. 3F) as a whole and the most-capable HSAM individuals (Fig. 3G) had nonzero susceptibility to semiautobiographical false memories. Using a 2 (HSAM, control) × 3 (“yes,” “maybe,” “no”) Fisher’s exact test, we found no evidence for a difference in susceptibility (Fig. 3F) (P = 0.608). Comparing high PEQ HSAM to lower PEQ HSAM participants (Fig. 3G) yielded a similar nonsignificant result (Fisher’s exact test P = 0.721). Excerpts from transcripts of a HSAM and control participants demonstrating these false memories are available in Sample Nonexistent News-Footage Interview Transcript Excerpts.

Finally, we also found susceptibility to memory distortions in the imagination inflation and emotion memory consistency paradigms in both HSAM individuals and controls (Figs. S4 and S5), with no evidence for enhanced resistance to distortion in the HSAM group. Table S1 summarizes both the autobiographical memory scores and memory distortion measures for each HSAM in the analysis, and suggests that no participant was immune to memory distortion. In addition, we found no consistent relationship between age and susceptibility to memory distortion.

Discussion

Prior HSAM research showed a remarkable ability in these individuals to recall even distant autobiographical information with an exceptional level of accuracy. This finding might imply that this population would be one of the most likely groups to be immune to memory distortions. However, we found that HSAM participants were as comparably susceptible to memory distortions as controls. This result was true on both relatively neutral word lists and more emotionally involved tasks. HSAM individuals showed normal levels of susceptibility to misremembering nonexistent news footage when misleading suggestion or imagination exercises were given. Significant news events, such as the crash of flight United 93 on September 11, 2001, are semiautobiographical in nature. These are events that HSAM participants usually recall with far greater accuracy and detail than controls, at least in the absence of misinformation and other distorting influences. Given that we had reason to expect HSAM individuals to be one of the least likely groups in the population to be vulnerable to memory distortions, this set of results, combined with previous research, gives credence to the hypothesis that potentially fallible memory reconstruction mechanisms are ubiquitous and a part of normal human memory. In most situations the reconstructive processes involved in memory are accurate. However, situations that make them inaccurate in the typical population will also make them inaccurate in this special population.

HSAM participants had significantly more OFM in the misinformation task than controls. This result indicates that HSAM participants, like others, are using memory reconstruction at the time of recall and that they are vulnerable to confusing one source (photos) from another (text narratives). To better understand this result, we compared HSAM individuals to controls on individual difference measures that could indicate a strong tendency to attend to and visualize the misinformation narratives. Indeed, we found that on the measures of absorption (Tellegen Absorption Scale) and fantasy proneness (Creative Experiences Questionnaire) HSAM participants were significantly higher than controls. The absorption measure captures “openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences” (27), and the fantasy-proneness measure involves the tendency to have vivid childhood memories and fantasize in a way that feels real (28). Controlling for these measures in a multiple regression eliminated the statistically significant difference between HSAM individuals and controls on OFM (Table S2). This analysis implies that absorption accounts for at least some of the reason that HSAM participants had more OFM, and that could be because of a deeper involvement or visualization during the misinformation narratives.

Because HSAM individuals outperform controls on autobiographical memory tasks, and because emotion is thought to play a role in the encoding of such events, it was quite possible that HSAM participants would be less susceptible to distortion of emotional information than controls. However, we found no evidence of this on the DRM test when we compared the most emotionally arousing critical lures to the most neutral words. Nor did we find conclusive evidence of this on the nonexistent news footage or imagination inflation task involving a news report of a potentially emotion-laden nationally significant plane crash. We did find that HSAM individuals were more consistent than controls in remembering some types of emotions, but were as inconsistent as controls on others (Fig. S5).

Another way to view HSAM individuals is as experts in the domain of their own autobiographical past. There is some evidence that experts are more likely to experience false memory for domain-relevant material using DRM word lists (29). Although in the present study we did not find higher false memories in HSAM individuals’ own domain of expertise, our conclusion that HSAM individuals use reconstructive retrieval processes to access their domain of expertise is compatible with that previous research.

HSAM individuals are a newly discovered, scientifically interesting group. The present results build on previous HSAM research that identified their unusually high autobiographical ability (19–21). On daily life details from their personal past, HSAM individuals have abundant and accurate recall (20). Our findings do not contradict this. In fact, in the nonexistent news-footage interviews we found examples of HSAM individuals’ rich and very detailed autobiographical memory that were congruent with past research (Example of a HSAM Individual’s Response that Demonstrated Detailed Autobiographical Memory Ability). We also know that their exceptional ability does not extend to traditional, nonautobiographical, and neutral laboratory tests of memory with relatively short study–test intervals (20). Similar results were observed in the current study as we observed similar performance to controls when photographs were used in recognition memory testing. We should note that HSAM participants were slightly more accurate at recognizing presented words in the DRM task. Their advantage here is not of the magnitude observed for autobiographical memory. The present study adds the knowledge that HSAM individuals as a group are comparably susceptible to a number of memory-distortion phenomena. Extraordinary autobiographical memory accuracy does not necessarily imply false-memory immunity. Despite their apparent accuracy of an extremely large memory store, HSAM individuals seem to be using the same reconstructive memory mechanisms that people with typical memory use.

It seems paradoxical that the HSAM group showed vulnerability to memory distortion yet remember an abundant amount of autobiographical information accurately for years. Their abundant accuracy could be the end result of strong autobiographical memory traces combined with little or no misinformation. If reminders of their personal past, such as diaries, photos, videos, conversations with family, news stories, and so forth, contain little misinformation then there may be very little distortion in their recall. In addition, it also seems puzzling why HSAM individuals remember some trivial details, such as what they had for lunch 10 y ago, but not others, such as words on a word list or photographs in a slideshow. The answer to this may be that they may extract some personally relevant meaning from only some trivial details and weave them into the narrative for a given day.

There is a question as to whether the participants were confidently reporting genuine memory distortions or merely guessing or making mistakes. Although we cannot be completely sure that a participant really experienced a visual false memory, we did ask questions that were designed to try to ascertain whether actual distortion was occurring. For example, in the DRM word-list procedure, the vast difference in endorsement of critical lures (about 70%) compared with unrelated distractors (about 20%) tells us that a good proportion of the critical lure endorsements are false reports/memories, rather than guesses. In the misinformation procedure, we found significantly higher misinformation endorsement in the experimental group compared with the control group, which means that at least some of the memory errors are not merely guesses or mistakes. We also had a source test in which many participants confirmed they had seen a misinformation detail in the original photographs, indicating relatively high confidence of a false memory. In the nonexistent news-footage procedure, the in-depth and detailed interview revealed that some participants had high confidence in their false memory because they gave false details, or by a high score on the final question: “How well do you remember seeing the video, from 1 = no memory at all, to 10 = very clear memory?” Of those who said they had seen the video, 56% gave a score on this scale above 5, suggesting that many were confident of their false memory (see also transcripts in Sample Nonexistent News-Footage Interview Transcript Excerpts).

A small sample size may typically pose limitations, but in this case it did not because we found typical levels of memory distortions in HSAM participants and controls. In all cases the rates were reliably above zero and in several cases the HSAM participants were showing at least trends toward higher levels of false memories. In addition, one could argue that the nonexistent news-footage target event was only semiautobiographical in nature, and not a fully personal memory. This aspect is both a strength and a weakness: on the one hand 9/11 was a public event that we know most people experienced and we know for sure the footage does not exist, but on the other hand it may not have been as personally significant as are other autobiographical events (e.g., weddings).

HSAM individuals possess a remarkable autobiographical memory. However, these results show that even they are not immune to episodic memory distortions. Whatever the source of their exceptional autobiographical memory ability is, this does not prevent them from having memory distortions. Although it is always possible that some group might be found to be immune to memory distortions, none has as yet been discovered.

Materials and Methods

Over two sessions, 1 wk apart, 20 HSAM and 38 age- and gender-matched controls participated in a number of memory distortion tasks. Twenty DRM associative word lists were presented, followed by test. Misinformation paradigm materials were presented in the form of photographical slideshows, text narratives with some misleading items, and memory and source tests. Nonexistent news footage was suggested both in computer questionnaires and in verbal interviews.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Larry Cahill and Elizabeth S. Parker for their previous research on highly superior autobiographical memory; Nancy Collett; and all the research assistants, including Fellows of University of California at Irvine’s Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program. This research was supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (L.P.), Sigma-Xi Grant-in-Aid (to L.P.), the Gerard Family Trust (J.L.M.), Unither Neurosciences (J.L.M.), Public Health Service National Institute of Mental Health MH12526 (to J.L.M.), and National Institutes of Health Grant 1R01AG034613 (to C.E.L.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 20856.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1314373110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bartlett FC. Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus EF. Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learn Mem. 2005;12(4):361–366. doi: 10.1101/lm.94705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz AN. Autobiographical memory as a reconstructive process. Can J Psychol. 1989;43(4):512–517. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deese J. On the prediction of occurrence of particular verbal intrusions in immediate recall. J Exp Psychol. 1959;58(1):17–22. doi: 10.1037/h0046671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roediger HL, McDermott KB. Creating false memories: Remembering words not presented in lists. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1995;21(4):803–814. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loftus EF, Palmer JC. Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1974;13(5):585–589. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loftus EF, Miller DG, Burns HJ. Semantic integration of verbal information into a visual memory. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn. 1978;4(1):19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crombag HFM, Wagenaar WA, van Koppen PJ. Crashing memories and the problem of ‘source monitoring.’. Appl Cogn Psychol. 1996;10(2):95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smeets T, Telgen S, Ost J, Jelicic M, Merckelbach H. What’s behind crashing memories? Appl Cogn Psychol. 2009;23(9):1333–1341. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garry M, Manning CG, Loftus EF, Sherman SJ. Imagination inflation: Imagining a childhood event inflates confidence that it occurred. Psychon Bull Rev. 1996;3(2):208–214. doi: 10.3758/BF03212420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine LJ. Reconstructing memory for emotions. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1997;126(2):165–177. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland R, Hayne H. Age-related changes in the misinformation effect. J Exp Child Psychol. 2001;79(4):388–404. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell KJ, Johnson MK, Mather M. Source monitoring and suggestibility to misinformation: Adult age-related differences. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2003;17(1):107–119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brainerd CJ, Reyna VF. Fuzzy-trace theory and false memory. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;11(5):164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loftus EF, Loftus GR. On the permanence of stored information in the human brain. Am Psychol. 1980;35(5):409–420. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.5.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson MK, Hashtroudi S, Lindsay DS. Source monitoring. Psychol Bull. 1993;114(1):3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins AM, Loftus EF. A spreading activation theory of semantic processing. Psychol Rev. 1975;82(6):407–428. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallo DA, Roediger HL. Evidence for associative activation and monitoring. J Mem Lang. 2002;47(3):469–497. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker ES, Cahill L, McGaugh JL. A case of unusual autobiographical remembering. Neurocase. 2006;12(1):35–49. doi: 10.1080/13554790500473680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LePort AKR, et al. Behavioral and neuroanatomical investigation of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2012;98(1):78–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ally BA, Hussey EP, Donahue MJ. A case of hyperthymesia: Rethinking the role of the amygdala in autobiographical memory. Neurocase. 2013;19(2):166–181. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2011.654225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luria AR. The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About a Vast Memory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt E, Love T. In: Coding Processes in Human Memory. Melton AW, Martin E, editors. Washington, DC: Winston-Wiley; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon P, Valentine E, Wilding JM. One man’s memory: A study of a mnemonist. Br J Psychol. 1984;75(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilding J, Valentine E. Superior Memory. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu B, et al. Individual differences in false memory from misinformation: Cognitive factors. Memory. 2010;18(5):543–555. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2010.487051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tellegen A, Atkinson G. Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. J Abnorm Psychol. 1974;83(3):268–277. doi: 10.1037/h0036681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merckelbach H, Horselenberg R, Muris P. The Creative Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ) Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31(6):987–995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castel AD, McCabe DP, Roediger HL, 3rd, Heitman JL. The dark side of expertise: Domain-specific memory errors. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(1):3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.