Significance

The ribosome decodes genetic information and synthesizes proteins in all living organisms. To translate the genetic information, the ribosome binds tRNA. During polypeptide chain elongation, the tRNA is moved together with the mRNA through the ribosome. This movement is called translocation and involves precisely coordinated steps that include binding of a protein called elongation factor G (EF-G). How exactly EF-G drives translocation is not fully understood. We show in this study a detailed three-dimensional molecular image of the ribosome bound to EF-G and two tRNAs, just before the tRNAs are translocated. The image provides mechanistic clues to how EF-G promotes tRNA translocation.

Keywords: A/P* hybrid state, translation, single particle analysis, FREALIGN, real-space refinement

Abstract

During protein synthesis, tRNAs and their associated mRNA codons move sequentially on the ribosome from the A (aminoacyl) site to the P (peptidyl) site to the E (exit) site in a process catalyzed by a universally conserved ribosome-dependent GTPase [elongation factor G (EF-G) in prokaryotes and elongation factor 2 (EF-2) in eukaryotes]. Although the high-resolution structure of EF-G bound to the posttranslocation ribosome has been determined, the pretranslocation conformation of the ribosome bound with EF-G and A-site tRNA has evaded visualization owing to the transient nature of this state. Here we use electron cryomicroscopy to determine the structure of the 70S ribosome with EF-G, which is trapped in the pretranslocation state using antibiotic viomycin. Comparison with the posttranslocation ribosome shows that the small subunit of the pretranslocation ribosome is rotated by ∼12° relative to the large subunit. Domain IV of EF-G is positioned in the cleft between the body and head of the small subunit outwardly of the A site and contacts the A-site tRNA. Our findings suggest a model in which domain IV of EF-G promotes the translocation of tRNA from the A to the P site as the small ribosome subunit spontaneously rotates back from the hybrid, rotated state into the nonrotated posttranslocation state.

The ribosome decodes genetic information and synthesizes proteins in all living organisms. Although the movement of tRNA and mRNA through the ribosome is fundamental for protein synthesis, the molecular mechanism of translocation is not fully understood. Translocation occurs in two sequential steps (1). Subsequent to the peptidyl-transfer reaction, the acceptor ends of the peptidyl- and deacylated tRNAs first move spontaneously relative to the large (50S) ribosomal subunit, from the classic A/A and P/P states into the hybrid A/P and P/E states (A, aminoacyl; P, peptidyl; E, exit). In the second step, elongation factor G (EF-G) catalyzes a coupled movement of the anticodon stem-loops of tRNAs and mRNA on the small (30S) ribosomal subunit, placing tRNAs into the posttranslocation P/P and E/E states. The movement of tRNAs into the hybrid states is accompanied by a counterclockwise rotation of the small (30S) subunit relative to the large (50S) subunit (2–5). Translocation of mRNA and anticodon stem-loops of tRNAs is completed in the presence of EF-G during reverse (clockwise) rotation of the small subunit (6–8).

Although remarkable progress in studies of translocation has been made in recent years, important questions remain unanswered: how does EF-G rectify nonproductive spontaneous ratchet-like intersubunit rotation and tRNA fluctuations to produce efficient translocation? Does EF-G bias diffusion-driven movements of tRNA, or does it promote translocation by converting energy derived from GTP hydrolysis into mechanical movement? Answers to these questions would benefit from the 3D reconstruction of all intermediates of the translocation pathway. Several structures of EF-G–ribosome complexes in which EF-G was bound either to the nonrotated classic state or to the rotated hybrid states of the ribosome have been determined by X-ray crystallography (9–13) and electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM) (5, 14, 15). Despite significant differences in ribosome conformations, none of the known EF-G–ribosome structures contain A-site peptidyl-tRNA. In most of the available structures, domain IV of EF-G, which is known to be critical for translocation, is bound to the 30S A site (5, 9–12). Because the 30S A site cannot be simultaneously occupied by a tRNA and domain IV of EF-G, this conformation of EF-G–ribosome complex is not compatible with a pretranslocation state. An attempt to visualize EF-G bound to the pretranslocation ribosome containing both A- and P-site tRNAs using cryo-EM (16) produced density maps that lacked structural detail and are considered unreliable (17) because of their low (18–20 Å) resolution. A conformation of EF-G–ribosome complex possibly compatible with the pretranslocation state was recently observed in two cryo-EM (15) and crystal (13) structures of EF-G–ribosome complexes containing a single P-site tRNA. In these structures, EF-G displayed a conformation similar to previously observed conformations in other EF-G–ribosome complexes. However, domain IV of EF-G was not fully docked into the A site owing to a large (∼18°) swiveling of the 30S head along the direction of tRNA translocation. Nevertheless, because A-site tRNA was not present, these structures do not directly report on the pretranslocation state containing EF-G and tRNAs in the A and P sites.

Here we present a cryo-EM reconstruction of the pretranslocation complex at 7.6-Å resolution, obtained by increasing complex stability with viomycin and using a classification algorithm to distinguish between different ribosome conformations in a heterogeneous dataset (18). The conformation of EF-G observed in this structure is significantly different from all previously seen structures of EF-G–ribosome complexes, providing evidence that EF-G undergoes significant structural rearrangement during translocation.

Results

Overall Structure.

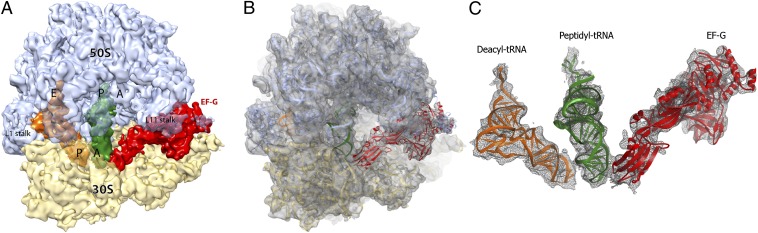

To gain insight into the mechanism of translocation, we designed experiments to determine the structure of EF-G–ribosome trapped in the pretranslocation state using cryo-EM. Translocation, which normally occurs upon EF-G•GTP binding, was inhibited by adding antibiotic viomycin to Escherichia coli ribosomes containing dipeptidyl N-acetyl-Met-Phe-tRNAPhe in the A site and deacylated tRNAMet in the P site. Viomycin also stabilizes the hybrid-state conformation of the ribosome (3, 19, 20) but does not interfere with EF-G binding to the ribosome or GTP hydrolysis by EF-G (21, 22). The EF-G–ribosome complex was assembled in the presence of GTP and fusidic acid (Fus), an antibiotic that inhibits EF-G release after GTP hydrolysis. Fus does not interfere with translocation and GTP hydrolysis (23, 24). We recorded and sorted more than 1.3 million cryo-EM images (Fig. S1) of assembled ribosomal complexes to generate five distinct classes (Fig. S2). One of these classes (class V) shows a previously unseen ribosome complex at 7.6-Å resolution containing EF-G and tRNAs bound to A and P sites of the small subunit (Fig. 1A). A structural model of the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex was conservatively fitted into the map by rigid-body real-space refinement (25, 26) (Figs. 1B and Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

(A–C) Structure of E. coli 70S ribosome–EF-G complex trapped in the pretranslocation state. (A) A 7.6-Å cryo-EM map of the EF-G–ribosome complex. Density corresponding to the 30S subunit is shown in yellow, 50S in light blue, EF-G in red, peptidyl-tRNA in dark green, and deacylated tRNA in orange. (B) Ribbon representation of the refined structure of the EF-G–ribosome complex fitted into the cryo-EM map. The 30S subunit is shown in yellow, the 50S subunit in light blue, EF-G in red, peptidyl-tRNA in dark green, and deacylated tRNA in orange. The density of the cryo-EM map is shown in transparent gray. (C) Cryo-EM map (gray mesh) and secondary-structure rendering of EF-G (red), peptidyl (dark green), and deacyl (orange) tRNAs in the pretranslocation complex.

The cryo-EM map of the pretranslocation complex (class V; Fig. S2) shows clear density for A- and P-site tRNAs, EF-G, and viomycin (Fig. S4A). The latter is bound between helix 44 of 16S and helix 69 of 23S rRNA as previously seen in the crystal structures of viomycin–ribosome complexes (11, 27). At this site viomycin does not directly contact EF-G, consistent with previous studies suggesting that viomycin inhibits translocation by stabilizing peptidyl-tRNA in the A site without interfering with EF-G binding or GTP hydrolysis (21, 22). Surprisingly, there is no clear density in the map that can be attributed to Fus in this class (Fig. S4E). This contrasts the presence of density for Fus in our map for the nonrotated EF-G–ribosome complex containing P- and E-site tRNAs (class II; Figs. S2 and S4F), consistent with the previously determined crystal structure of EF-G•GDP•Fus bound to the posttranslocation ribosome (9). At the current resolution of the map of the pretranslocation complex (class V) we cannot entirely rule out that Fus is bound. However, the density for EF-G suggests that domains II and III partially occluded the Fus binding site after rearrangement (Fig. S4E), further corroborating the absence of Fus.

At the current resolution, we are also not able to determine with certainty which nucleotide (GDP, GDP/Pi, or GTP) is bound to EF-G. However, neither viomycin nor Fus inhibit single-round GTP hydrolysis (28, 29). Viomycin does not affect Pi release (30), whereas Fus leads to modest (∼fourfold) inhibition of single-turnover Pi release (24, 29). Because the rate of Pi release is 20 s−1 in the presence of viomycin (30), Pi is expected to be released on the time scale of our sample preparation. Hence, in our pretranslocation structure, GDP rather than GDP/Pi or GTP is expected to be bound to EF-G. Although Fus is not likely present in our structure, EF-G binding is likely stabilized by viomycin, which inhibits EF-G release from the ribosome (21).

The newly observed complex shows the ribosome in a conformation that is globally similar to a number of other structures of the rotated, hybrid-state ribosomes obtained by cryo-EM (2, 4, 31) and X-ray crystallography (32) in the absence of EF-G and antibiotics. Its structure is also consistent with kinetic studies of translocation suggesting that EF-G transiently stabilizes the rotated, hybrid-state conformation of the ribosome during translocation (7, 33, 34). Thus, although we cannot completely rule out that we trapped an off-pathway EF-G–ribosome complex, our cryo-EM reconstruction of pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex likely represents an authentic, on-pathway intermediate of translocation.

Structure of EF-G in the Pretranslocation State.

In contrast to all previous cryo-EM and X-ray structures of EF-G bound to either nonrotated, classic (9), or rotated, hybrid-state ribosomes (5, 10–13, 15), we observe domain IV of EF-G in the pretranslocation state outside of the 30S A site, which is occupied by peptidyl-tRNA (Fig. 1C). The conserved loop at the tip of domain IV of EF-G (residues 507–514 in E. coli EF-G) makes extensive contact with the anticodon loop of the A-site tRNA (Fig. 1C). In the posttranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex (9), the same loop is inserted into the minor groove of the helix formed by the P-site tRNA and mRNA codon. Thus, domain IV of EF-G maintains its interaction with peptidyl-tRNA as tRNA translocates from the A to P site. This observation supports the hypothesis that the interaction between domain IV of EF-G and A-site tRNA facilitates translocation by displacing conserved bases of 16S rRNA G530, A1492, and A1493, which stabilize tRNA binding to the A site by interacting with the minor groove of the codon–anticodon helix (9).

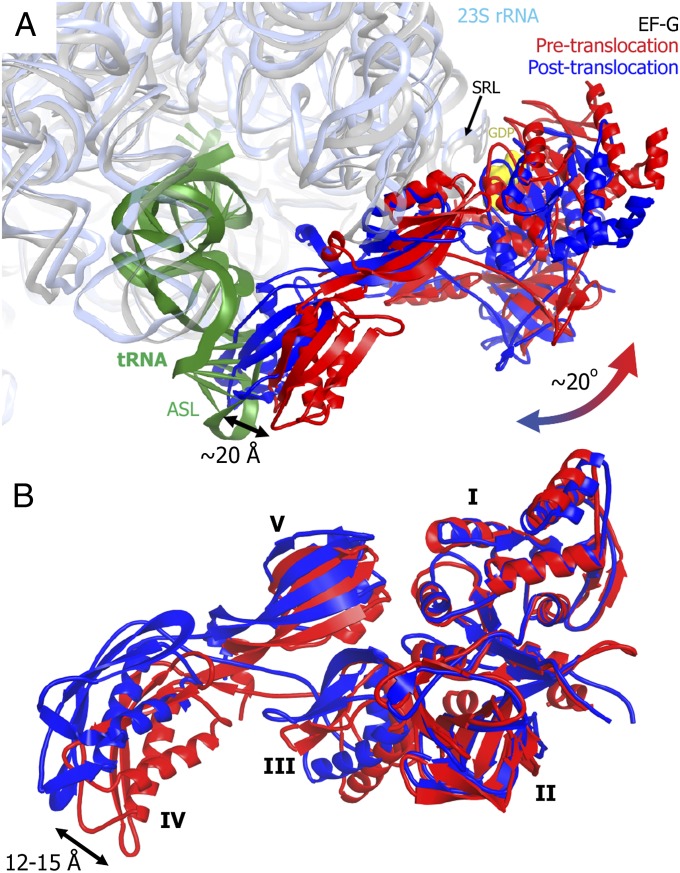

Compared with the posttranslocation complex, the tip of domain IV is located more than 20 Å farther from the A site and toward the periphery of the 30S subunit (Fig. 2A). The large movement of EF-G as a whole between the pre- and posttranslocation states results mainly from a ∼20° rotation of EF-G around the universally conserved sarcin–ricin loop (SRL, nucleotides 2653–2667 of 23S rRNA). The SRL, which interacts with the GTP binding pocket of domain I of EF-G (9, 35), remains static in the transition from the pre- to posttranslocation state of the EF-G ribosome complex. This is consistent with a previously proposed hypothesis that EF-G rotation around the SRL allows domain IV of EF-G to avoid a steric clash with the A-site tRNA in the pretranslocation ribosome (36).

Fig. 2.

Structural rearrangement of EF-G during translocation. (A) EF-G movement relative to the ribosome during translocation. Peptidyl-tRNA (dark green), 23S rRNA (light blue), and EF-G (red) in the pretranslocation ribosome (this work) are superposed with 23S rRNA (gray) and EF-G (blue) in the posttranslocation ribosome [Protein Data Bank ID 2WRI (9)]. The superposition was obtained by structural alignment of respective 23S rRNAs. The arrow indicates a ∼20° rotation of EF-G around the SRL of 23S rRNA during transition from the pre- to posttranslocation state. (B) Interdomain rearrangement of EF-G during translocation. Pretranslocation (red) and posttranslocation (blue) conformations of EF-G are superposed by structural alignment of domains I and II. EF-G domains are labeled by Latin numbers. The arrow indicates movement of the tip of domain IV between the two structures.

In addition to the rotation around the SRL, EF-G undergoes an interdomain rearrangement. The superposition of domains I-II of EF-G bound to pre- and posttranslocation (9) ribosomes reveals a concerted movement of domains III, IV, and V relative to domains II and I, resulting in a shift of the tip of domain IV by up to 15 Å (Fig. 2B). The superposition of domains I-II of EF-G bound to pretranslocation ribosome and those of EF-G bound to a rotated ribosome with the vacant A site (11–13) also shows a concerted movement of domains III, IV, and V, resulting in a shift of domain IV by 10–15 Å (Fig. S5). These movements are consistent with previous reports implicating structural dynamics of EF-G in translocation. Indeed, restricting the conformational dynamics of EF-G by introducing an intramolecular disulfide cross-link between domains I and V was shown to abolish EF-G translocation activity (37). Furthermore, comparison of the crystal structures of ribosome-free EF-G (38–40) with the crystal structure of EF-G in the posttranslocation ribosome (9) reveals a significant structural rearrangement of domains III, IV, and V, resulting in movement of the tip of domain IV by up to 30 Å and indicating that EF-G is indeed dynamic. Our data demonstrate that domain IV of EF-G in pretranslocation ribosomes adopts an intermediate conformation between free EF-G and EF-G bound to the posttranslocation ribosome (Fig. S5D).

Structure of the Ribosome in the Pretranslocation State.

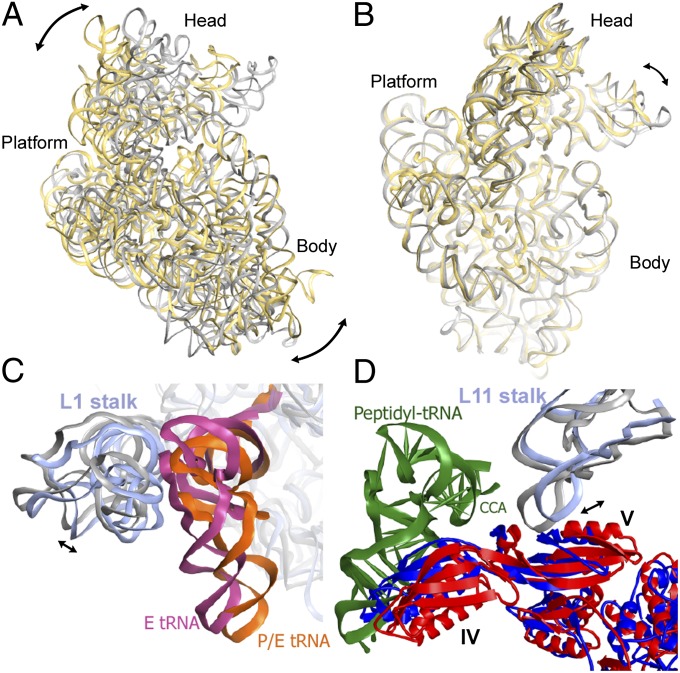

The pre- and posttranslocation EF-G–ribosome complexes differ not only in their EF-G configuration but also in the conformation of the ribosome. Compared with the crystal structure of the posttranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex (9), the small subunit in the pretranslocation ribosome is rotated counterclockwise by ∼12° relative to the large subunit (Fig. 3A). The head of the 30S subunit is swiveled by ∼3° relative to the 30S platform and body toward the E site (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the posttranslocation ribosome where two tRNAs are bound in classic P/P and E/E sites, the pretranslocation complex has its peptidyl- and deacylated tRNAs bound in hybrid A/P and P/E states, respectively. In the pretranslocation ribosome, the L1 stalk, a mobile domain of the large subunit, is moved inward by ∼5 Å and contacts the elbow of the P/E tRNA (Fig. 3C). Another mobile element of the large subunit, the L11 stalk is placed 7 Å farther from the A site than in the posttranslocation complex (Fig. 3D). Interactions between domain V of EF-G and the conserved loop of helix 43 of 23S rRNA (35) are similar in the pre- and posttranslocation states. Thus, the movement of the L11 stalk during translocation maintains the interactions of the stalk with EF-G as the latter rotates around the SRL (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of ribosome conformations in the pretranslocation and posttranslocation states. (A) Comparison of 16S rRNA of the small subunit in the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex (yellow, this work) with 16S rRNA in the posttranslocation ribosome (9) (gray), obtained by structural alignment of 23S rRNA from both ribosome structures (23S rRNA is not displayed for clarity). The superposition reveals a 12° counterclockwise rotation of the 30S subunit in the pretranslocation ribosome, as illustrated by the arrows. (B) Superposition of 16S rRNA of the small subunit in the pre- (yellow) and posttranslocation (9) (gray) EF-G–ribosome complexes obtained by structural alignment of the body and platform of the 16S rRNA from both structures. The superposition demonstrates a ∼3° rotation of the 30S head relative to the rest of the small subunit in the pretranslocation ribosome, as indicated by the arrow. (C) Close-up view of the 50S subunit showing the movement of the L1 stalk (helices 76–78 of 23S rRNA are shown). 23S rRNA in the pretranslocation ribosome is shown in light blue; 23S in the posttranslocation ribosome (9) is gray; deacylated tRNA in the P/E state is orange; E-site tRNA (9) is hot pink. (D) Close-up view of the 50S subunit demonstrating the movement of the L11 stalk (helices 42–44 of 23S rRNA are shown). The pretranslocation complex (this work) is shown in red (EF-G), light blue (23S rRNA), and dark green (peptidyl-tRNA). The posttranslocation complex is in blue (EF-G) and gray (23S rRNA). Superpositions in C and D were obtained by structural alignment of 23S rRNA from the pretranslocation (this work) and posttranslocation (9) EF-G–ribosome complexes.

In addition to the structure of EF-G bound to nonrotated, classic state ribosome (9), a number of EF-G–ribosome complexes lacking A-site tRNA and showing various degrees of intersubunit rotation and swiveling of the 30S head have been solved recently using X-ray crystallography (10–13). Our structure of the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex shows an intersubunit rotation that is larger than the rotations seen in any of the EF-G–ribosome crystal structures (12° vs. 7°). In contrast, our pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex exhibits a 30S head swivel (3°) that is smaller than that seen in any of the crystal structures. Hence, comparison of ribosome conformations in different EF-G–ribosome complexes supports results of recent kinetic experiments (8) suggesting that intersubunit rotation and head swiveling may occur sequentially rather than simultaneously during ribosomal translocation.

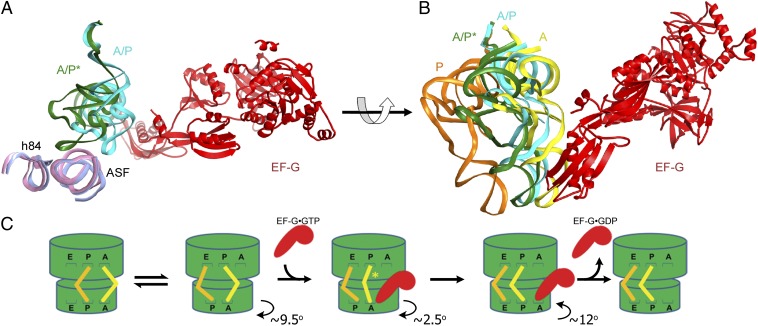

To analyze how EF-G binding affects the conformation of the pretranslocation ribosome, we compared the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex with a structure of the EF-G-free ribosome containing tRNAs in the A/P and P/E states (Fig. S6). The latter was obtained by real-space refinement of the ribosome structure to a 7.6-Å resolution cryo-EM map of a respective class of ribosomes in our dataset (class IV; Methods). The ∼9.5° of intersubunit rotation and the positioning of tRNAs in our refined structure of the EF-G-free pretranslocation complex closely resemble those observed in previous cryo-EM (2, 4, 31) and crystal (32, 41) structures of the rotated, hybrid-state ribosomal complexes that do not contain bound EF-G. Comparison of our EF-G-bound and EF-G-free pretranslocation complexes reveals that EF-G binding induces counterclockwise rotation of the small subunit by an extra 2.5° (Fig. S7), as well as movement of the elbow of the A-site tRNA by ∼25 Å toward the P site (Fig. 4A). In the EF-G-free structure, peptidyl-tRNA is bound in the hybrid A/P state as was observed in previous cryo-EM structures (2, 4). In this state, the anticodon stem-loop and elbow of the tRNA interact with the 30S A site and the A-site finger (helix 38) of 23S rRNA, respectively, whereas the 3′-CCA end of the tRNA is in the P site of the 50S subunit (Fig. 4 A and B). In the EF-G-bound pretranslocation complex, the peptidyl-tRNA retains its interactions with the 30S A and 50S P sites. However, its elbow is rotated around the A-site finger and positioned to contact helix 84 of 23S rRNA (Fig. 4 A and B). Thus, EF-G binding to the pretranslocation ribosome stabilizes peptidyl-tRNA in a distinct intermediate state of A-site tRNA translocation that we propose to name the A/P* hybrid state (Fig. 4C). A similar conformation of peptidyl-tRNA was observed in cryo-EM reconstructions of bacterial ribosome–tRNA complexes in the absence of EF-G (31), and of pretranslocation mammalian ribosomes obtained in the absence of EF-2 (42), suggesting that the A/P* state may be sampled spontaneously. Indeed, spontaneous sampling of two hybrid states of tRNA binding that differ in the position of the elbow of A-site tRNA was observed in pretranslocation ribosomes using single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) (43). Comparison of pre- and posttranslocation complexes of the bacterial ribosome suggests that translocation of the A-site tRNA into the P site occurs at minimum in three consecutive steps. First, the acceptor end of tRNA shifts on the large subunit after peptidyl transfer (A/P state). Second, the tRNA elbow moves upon EF-G binding, positioning the peptidyl-tRNA in the A/P* state. In the third step, the anticodon stem loop of peptidyl-tRNA translocates into the P/P state during the reverse, clockwise rotation of the small subunit (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Intermediate states of tRNA translocation. (A) Structural alignment of 23S rRNA in cryo-EM structures of the EF-G-free (light pink) and EF-G-bound (light blue) pretranslocation ribosomes (both determined in this work) reveals that EF-G binding induces the movement of peptidyl-tRNA into the A/P* hybrid state described in this work. For clarity, only EF-G (red), peptidyl-tRNA, and helices 38 (the A-site finger, ASF) and 84 (h84) of 23S rRNA are shown, whereas other structural components of the ribosome are omitted. Peptidyl-tRNA bound to the A/P hybrid state in the EF-G-free ribosome is shown in cyan; peptidyl-tRNA bound to the A/P* hybrid state in the EF-G-bound ribosome complex is shown in dark green. (B) Position of the intermediate tRNA A/P* state in the pretranslocation EF-G-bound ribosome structure (dark green) relative to the A/P state of the EF-G-free hybrid-state ribosome (cyan) and classic A/A- (yellow) and P/P- (orange) tRNAs of the nonrotated, classic-state ribosome (9, 53). Superpositions in A and B were obtained by structural alignment of 23S rRNA from their respective complexes. (C) Schematic depiction of intersubunit rotation and tRNA movement during translocation. After peptidyl-transfer from the P- (orange) to the A-site (yellow) tRNA, the ribosome undergoes spontaneous fluctuations between the nonrotated (classic) and rotated (hybrid) states. Binding of EF-G•GTP (red) induces an extra 2.5° rotation of the 30S subunit (in addition to the 9.5° rotation observed in the EF-G-free hybrid-state ribosome) and shifts peptidyl-tRNA into the A/P* state. Upon subsequent clockwise rotation of the small subunit, domain IV of EF-G moves into the 30S A site and promotes the translocation of tRNAs and their associated mRNA codons on the small subunit. tRNA translocation on the small subunit is followed by dissociation of EF-G•GDP from the ribosome. The 30S head movement is not displayed for clarity. The translocation pathway may include additional intermediates that are not depicted in this scheme.

Discussion

Our cryo-EM reconstruction reveals the structure of a long-hypothesized intermediate of ribosome translocation in which EF-G is bound to the pretranslocation ribosome. We stabilized this transient intermediate with viomycin, an antibiotic inhibiting translocation. In posttranslocation complexes domain IV of EF-G occupies the 30S A site, thus precluding tRNA binding at this site. In the pretranslocation state reported here EF-G adopts a conformation distinct from the posttranslocation state, permitting tRNA binding in the A site. Stabilization of the EF-G-bound pretranslocation state was possible because viomycin increases the affinity of peptidyl-tRNA to the A site more than 1,000-fold (21, 22). Because viomycin does not contact EF-G and was previously observed in a crystal structure of the ribosome with EF-G bound in the posttranslocation conformation (11), the pretranslocation conformation of EF-G observed in our structure is not directly induced by viomycin. Together with our finding that the structure of the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex is similar to other structures of rotated, hybrid-state ribosomes (2, 4, 31, 32), this suggests that our cryo-EM reconstruction of pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex represents an on-pathway intermediate of translocation.

Our structure shows a number of unique features, most notably the ∼12° rotation of the small ribosomal subunit and the adoption of the A/P* state by the peptidyl-tRNA in response to EF-G binding, and brings insights into the mechanism of translocation. Fig. 4C provides a minimal description of the translocation mechanism that can be inferred from comparing structures of pre- and posttranslocation states of EF-G–ribosome as well as structure of EF-G-free pretranslocation ribosome. Translocation of mRNA and the anticodon stem-loops of tRNAs was shown to occur during the movement of the small ribosomal subunit from the rotated hybrid state back into the nonrotated classic conformation (7). Comparison of pre- and posttranslocation states of the EF-G–ribosome complex suggests that domain IV of EF-G, which contacts the A-site tRNA, plays a central role in translocation: upon reverse (clockwise) rotation of the small subunit, domain IV of EF-G acts as a steric hindrance for the return of peptidyl-tRNA from hybrid A/P* into classic A/A state (Fig. 4B), pushing A-site tRNA in the forward direction (Fig. 4B). In the absence of EF-G, tRNA fluctuations between classic and hybrid states on the 50S subunit, as well as intersubunit rotation, can occur spontaneously at rates comparable to rates of EF-G-catalyzed mRNA translocation (19, 33, 43, 44). Therefore, it has been hypothesized that thermal energy is sufficient to drive tRNA and mRNA translocation upon spontaneous reverse rotation of the small subunit (15, 32, 45–47). The comparison of pre- and posttranslocation states of EF-G–ribosome complex now reveals how spontaneous intersubunit rotation may be rectified into translocation by EF-G binding to the ribosome.

Our structure of the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex exposes significant movement of EF-G domains III, IV, and V relative to domains I and II compared with the structures of ribosome-free EF-G and EF-G bound to the posttranslocation ribosome (Fig. S5D). In addition, EF-G as a whole undergoes a ∼20° rotation around the SRL of the 50S subunit in the course of translocation (Fig. 2A). The transition of EF-G from the conformation observed in our structure into the conformation observed in the posttranslocation ribosome (9) includes a movement of domain IV toward the A site. This structural rearrangement of EF-G may drive tRNA movement from the A to P site on the small subunit, thus promoting translocation.

Alternatively, movement of domain IV of EF-G to the A site of the small subunit may follow spontaneous movement of peptidyl-tRNA from the 30S A to P site, making tRNA translocation irreversible. Existing FRET and biochemical data do not provide evidence for frequent spontaneous fluctuations of tRNA between A and P sites of the 30S subunit in the absence of EF-G. Therefore, for this translocation mechanism to be possible, EF-G must destabilize binding of peptidyl-tRNA to the A site. The destabilization may then lead to spontaneous movement of tRNAs between binding sites, and EF-G could, in addition to its destabilization action, bias the movement toward the P site. Higher-resolution structures of pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complexes may provide evidence for the destabilization of A-site tRNA by EF-G. In addition, smFRET experiments may allow distinction between coincident movement of domain IV of EF-G and tRNA, and EF-G movement that follows that of tRNA.

Although comparison of the pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex obtained in this work with the structure of posttranslocation EF-G–ribosome complex previously visualized by X-ray crystallography provides important clues about the mechanism of EF-G-induced translocation of tRNA and mRNA, additional intermediates of translocation likely exist. A large (up to 18°) swivel of the 30S head was observed in several EF-G–ribosome structures (11, 13, 15). This movement was hypothesized to open a wide (∼20 Å) path for tRNA translocation between the P and E site on the small subunit that is otherwise constricted by RNA residues of the 30S head and platform (48). Recent kinetic studies (8) suggested that intersubunit rotation precedes the 30S head swiveling, whereas mRNA translocation, reverse rotation of body and platform of the small subunit, and back-swiveling of the 30S head seem to occur concurrently. Our pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome structure shows a large (12°) degree of intersubunit rotation and a relatively small (3°) 30S head swivel. Hence, our pretranslocation EF-G–ribosome structure likely represents an early translocation intermediate, formation of which is probably followed by additional 30S head swiveling. Further studies will be required to reconstruct the complete translocation pathway.

Methods

A detailed description of the study methods can be found in SI Methods.

EF-G-Bound Ribosome Preparation.

Fus and viomycin were purchased from Sigma and USP, respectively; tRNAMet and tRNAPhe from E. coli were purchased from MP Biomedicals and Chemblock, respectively. E. coli ribosomes, aminocylated tRNAs, his-tagged EF-Tu, and EF-G were prepared as previously described (6). Pretranslocation complex was assembled by incubating 70S ribosomes (0.4 μM) with N-acetyl-Met-tRNAMet (0.8 μM) and mRNA m32 (6) (0.8 μM) in buffer containing 30 mM Hepes·KOH (pH 7.5), 6 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl, 2 mM spermidine, 0.1 mM spermine, and 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol followed by addition of EF-Tu•GTP•Phe-tRNAPhe ternary complex (0.8 μM). Pretranslocation ribosomes were incubated with viomycin (0.5 mM), and then EF-G (4 μM) was added together with GTP (0.5 mM) and Fus (0.5 mM). EF-G–ribosome complexes were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Cryo-EM Data Collection and Image Analysis.

More than 1.3 million cryo-EM images of ribosome complexes (Fig. S1) were acquired using an FEI Titan Krios electron microscope and sorted into five distinct classes using FREALIGN (18) (Fig. S2). The remaining classes did not show distinct features and most likely represented misaligned or incomplete ribosomes.

Modeling of the Cryo-EM Maps Using Atomic Models.

The crystal structure of the hybrid-state 70S•tRNA•RRF complex (32) (excluding the RRF molecule) was used as a starting model for structure fitting in Chimera (49). A homology model of E. coli EF-G was created using the SWISS-MODEL (50) from Thermus thermophilus EF-G (Protein Data Bank ID 2BM0) (51). Secondary structure elements of the ribosome complexes were manually fitted and then refined using stereochemically restrained rigid-body real-space refinement (25, 26). The correlation coefficient between refined structures and cryo-EM maps (classes IV and V) is 0.86 for each complex. The refined model of EF-G fully accounts for the local cryo-EM density (Fig. S8). The all-atom rmsd between ribosomal RNAs of each refined model and the starting crystal structure (32) is 1.2 Å; all-atom rmsds between the six best models of EF-G also do not exceed 1.2 Å (Fig. S9), similar to the expected coordinate error of cryo-EM structures at 7.6-Å resolution (52).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jillian Dann for assistance with the purification of EF-G, Olivia R. Silva for assistance with real-space refinement, and Zhiheng Yu and Jason de la Cruz for help with collecting data on the Titan Krios microscope. The study was supported by the Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research and University of Massachusetts Medical School Center for AIDS Research (A.A.K.), National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to A.F.B.), and National Institutes of Health Grants GM-099719 (to D.N.E.), P30 GM092424 (to the Center for RNA Biology at University of Rochester), and P01 GM62580 (to N.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3J5T, 3J5U, 3J5W, and 3J5X). The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the EMDataBank, www.emdatabank.org (accession codes EMD-5796–EMD-5800).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1311423110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Moazed D, Noller HF. Intermediate states in the movement of transfer RNA in the ribosome. Nature. 1989;342(6246):142–148. doi: 10.1038/342142a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agirrezabala X, et al. Visualization of the hybrid state of tRNA binding promoted by spontaneous ratcheting of the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2008;32(2):190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ermolenko DN, et al. The antibiotic viomycin traps the ribosome in an intermediate state of translocation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(6):493–497. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julián P, et al. Structure of ratcheted ribosomes with tRNAs in hybrid states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(44):16924–16927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809587105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valle M, et al. Locking and unlocking of ribosomal motions. Cell. 2003;114(1):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ermolenko DN, et al. Observation of intersubunit movement of the ribosome in solution using FRET. J Mol Biol. 2007;370(3):530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ermolenko DN, Noller HF. mRNA translocation occurs during the second step of ribosomal intersubunit rotation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(4):457–462. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo Z, Noller HF. Rotation of the head of the 30S ribosomal subunit during mRNA translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):20391–20394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218999109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao YG, et al. The structure of the ribosome with elongation factor G trapped in the posttranslocational state. Science. 2009;326(5953):694–699. doi: 10.1126/science.1179709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Feng S, Kumar V, Ero R, Gao YG. Structure of EF-G-ribosome complex in a pretranslocation state. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(9):1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulk A, Cate JH. Control of ribosomal subunit rotation by elongation factor G. Science. 2013;340(6140):1235970. doi: 10.1126/science.1235970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tourigny DS, Fernández IS, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Elongation factor G bound to the ribosome in an intermediate state of translocation. Science. 2013;340(6140):1235490. doi: 10.1126/science.1235490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou J, Lancaster L, Donohue JP, Noller HF. Crystal structures of EF-G-ribosome complexes trapped in intermediate states of translocation. Science. 2013;340(6140):1236086. doi: 10.1126/science.1236086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank J, Agrawal RK. A ratchet-like inter-subunit reorganization of the ribosome during translocation. Nature. 2000;406(6793):318–322. doi: 10.1038/35018597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ratje AH, et al. Head swivel on the ribosome facilitates translocation by means of intra-subunit tRNA hybrid sites. Nature. 2010;468(7324):713–716. doi: 10.1038/nature09547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark H, Rodnina MV, Wieden HJ, van Heel M, Wintermeyer W. Large-scale movement of elongation factor G and extensive conformational change of the ribosome during translocation. Cell. 2000;100(3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramakrishnan V. Ribosome structure and the mechanism of translation. Cell. 2002;108(4):557–572. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyumkis D, Brilot AF, Theobald DL, Grigorieff N. Likelihood-based classification of cryo-EM images using FREALIGN. J Struct Biol. 2013;183(3):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornish PV, Ermolenko DN, Noller HF, Ha T. Spontaneous intersubunit rotation in single ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2008;30(5):578–588. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, et al. Allosteric control of the ribosome by small-molecule antibiotics. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(9):957–963. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modolell J, Vázquez The inhibition of ribosomal translocation by viomycin. Eur J Biochem. 1977;81(3):491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peske F, Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. Conformational changes of the small ribosomal subunit during elongation factor G-dependent tRNA-mRNA translocation. J Mol Biol. 2004;343(5):1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodley JW, Zieve FJ, Lin L, Zieve ST. Formation of the ribosome-G factor-GDP complex in the presence of fusidic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969;37(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savelsbergh A, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. Distinct functions of elongation factor G in ribosome recycling and translocation. RNA. 2009;15(5):772–780. doi: 10.1261/rna.1592509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabiola F, Chapman MS. Fitting of high-resolution structures into electron microscopy reconstruction images. Structure. 2005;13(3):389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korostelev A, Bertram R, Chapman MS. Simulated-annealing real-space refinement as a tool in model building. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58(Pt 5):761–767. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902003402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanley RE, Blaha G, Grodzicki RL, Strickler MD, Steitz TA. The structures of the anti-tuberculosis antibiotics viomycin and capreomycin bound to the 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(3):289–293. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodnina MV, Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Wintermeyer W. Hydrolysis of GTP by elongation factor G drives tRNA movement on the ribosome. Nature. 1997;385(6611):37–41. doi: 10.1038/385037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo HS, et al. EF-G-dependent GTPase on the ribosome. Conformational change and fusidic acid inhibition. Biochemistry. 2006;45(8):2504–2514. doi: 10.1021/bi0516677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savelsbergh A, et al. An elongation factor G-induced ribosome rearrangement precedes tRNA-mRNA translocation. Mol Cell. 2003;11(6):1517–1523. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer N, Konevega AL, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina MV, Stark H. Ribosome dynamics and tRNA movement by time-resolved electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2010;466(7304):329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature09206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunkle JA, et al. Structures of the bacterial ribosome in classical and hybrid states of tRNA binding. Science. 2011;332(6032):981–984. doi: 10.1126/science.1202692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blanchard SC, Kim HD, Gonzalez RL, Jr, Puglisi JD, Chu S. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(35):12893–12898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pan D, Kirillov SV, Cooperman BS. Kinetically competent intermediates in the translocation step of protein synthesis. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moazed D, Robertson JM, Noller HF. Interaction of elongation factors EF-G and EF-Tu with a conserved loop in 23S RNA. Nature. 1988;334(6180):362–364. doi: 10.1038/334362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou J, Lancaster L, Trakhanov S, Noller HF. Crystal structure of release factor RF3 trapped in the GTP state on a rotated conformation of the ribosome. RNA. 2012;18(2):230–240. doi: 10.1261/rna.031187.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peske F, Matassova NB, Savelsbergh A, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. Conformationally restricted elongation factor G retains GTPase activity but is inactive in translocation on the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):501–505. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.AEvarsson A, et al. Three-dimensional structure of the ribosomal translocase: Elongation factor G from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 1994;13(16):3669–3677. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Czworkowski J, Wang J, Steitz TA, Moore PB. The crystal structure of elongation factor G complexed with GDP, at 2.7 A resolution. EMBO J. 1994;13(16):3661–3668. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06675.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Koripella RK, Sanyal S, Selmer M. Staphylococcus aureus elongation factor G—structure and analysis of a target for fusidic acid. FEBS J. 2010;277(18):3789–3803. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin H, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Crystal structure of the hybrid state of ribosome in complex with the guanosine triphosphatase release factor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(38):15798–15803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112185108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Budkevich T, et al. Structure and dynamics of the mammalian ribosomal pretranslocation complex. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2):214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munro JB, Altman RB, O’Connor N, Blanchard SC. Identification of two distinct hybrid state intermediates on the ribosome. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fei J, Kosuri P, MacDougall DD, Gonzalez RL., Jr Coupling of ribosomal L1 stalk and tRNA dynamics during translation elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;30(3):348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frank J, Gonzalez RL., Jr Structure and dynamics of a processive Brownian motor: The translating ribosome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:381–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-173330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spirin AS. The ribosome as an RNA-based molecular machine. RNA Biol. 2004;1(1):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ermolenko DN, Cornish PV, Ha T, Noller HF. Antibiotics that bind to the A site of the large ribosomal subunit can induce mRNA translocation. RNA. 2013;19(2):158–166. doi: 10.1261/rna.035964.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuwirth BS, et al. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 A resolution. Science. 2005;310(5749):827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1117230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: A web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansson S, Singh R, Gudkov AT, Liljas A, Logan DT. Structural insights into fusidic acid resistance and sensitivity in EF-G. J Mol Biol. 2005;348(4):939–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rossmann MG. Fitting atomic models into electron-microscopy maps. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56(Pt 10):1341–1349. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900009562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voorhees RM, Weixlbaumer A, Loakes D, Kelley AC, Ramakrishnan V. Insights into substrate stabilization from snapshots of the peptidyl transferase center of the intact 70S ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(5):528–533. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.