Significance

This study sheds light on how 9/11 catalyzed long-term changes in the political behaviors of victims’ families and neighbors. Political changes among associates of victims are important because system shocks like 9/11 can lead to rapid policy shifts, and relatives of victims often become leaders advocating for such shifts. I build upon prior research on the behavioral effects of tragic events by using a unique method of analysis. Rather than utilizing surveys, I link together individual-level government databases from before and after 9/11, and I measure the changes in the affected populations relative to similar populations that did not lose a relative or neighbor. The method I outline may prove useful in future studies of human behavior.

Keywords: terrorism, political participation, voting, big data, matching

Abstract

This article investigates the long-term effect of September 11, 2001 on the political behaviors of victims’ families and neighbors. Relative to comparable individuals, family members and residential neighbors of victims have become—and have stayed—significantly more active in politics in the last 12 years, and they have become more Republican on account of the terrorist attacks. The method used to demonstrate these findings leverages the random nature of the terrorist attack to estimate a causal effect and exploits new techniques to link multiple, individual-level, governmental databases to measure behavioral change without relying on surveys or aggregate analysis.

September 11, 2001’s (hereafter 9/11) effect on the United States population has been a topic of intrigue across the social sciences for the last 12 years. Short-term and long-term changes stemming from the attacks may help us understand how common citizens react to the stress and threat of mass terrorism. Following 9/11, researchers found heightened levels of posttraumatic stress across the country (1), especially close to the New York attacks (2), as well as increases in individuals’ trust in government (3) and conservative political attitudes (4). Heightened levels of stress and threat are linked to authoritarian political attitudes (5–7). Changes in political attitudes are consequential and measurable outcomes of the psychological effects of politicized violence.

Estimating the specific and long-term effects of the attacks on the families and neighbors of victims aids our understanding of terrorism, but also sheds light on individuals who have substantial influence in the shaping of public policy. Changes in the law often come when policy equilibria are punctuated by sudden events (8). September 11th was one such event, resulting in policy shifts in domestic security and foreign relations. However, 9/11 is just one example: natural disasters, acts of gun violence, child abductions, even corporate scandals can serve as shocks that catalyze long-lasting policy change. Victims of politicized tragedies can play an important role in shaping policy change. For example, parents of children murdered in the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting have become active in lobbying Congress to amend gun laws (for other examples, consult ref. 9). Families of 9/11 victims became similarly involved in politics following the attacks, primarily lobbying policymakers to advance anti-terrorism laws. (See, for example, the following organizations: Families of September 11th, 9/11 Families for a Safe and Strong America, Voices of September 11th, and September Eleventh Families for Peaceful Tomorrows.) Americans who lost loved ones in 9/11 are thus not only a population of interest for their connection to a major historical event, but their behavior holds lessons for understanding policy influence following system shocks.

To estimate behavioral change among 9/11 victims’ families and neighbors, I used a method of analysis that differs from past research in this area of study. It is a method that was not possible until recently because of improvements in public records and computational power. The behavior of victims’ close relations is studied not through surveys, as is typical of psychological and political behavioral research (e.g., refs. 4, 5, and 9), and not through analysis of aggregate patterns, as is typical, for example, in the study of behavioral effects of natural disasters (e.g., refs. 10–12), but rather by linking together multiple digital government databases that record individual-level behavior for many millions of people. By using individual-level data, I sidestepped biases stemming from ecological inference inherent in studies of aggregated data. Additionally, by using government records about individuals’ past behavior rather than information that is self-reported by individuals in surveys, I sidestepped misreporting biases. Misreporting bias is particularly problematic in the study of political participation because people tend to lie about their past record of voting, voter registration, and other behaviors generally perceived as socially desirable (13). To the extent that 9/11 families and neighbors feel a heightened sense of duty to participate in politics, they may be particularly prone to misreport their history of participation when they fail to participate.

Linking databases that capture political behavior before 9/11 with databases that capture political behavior following 9/11 enabled me to examine three components of behavioral change that would be more difficult using other methods. First, I examined evidence of change over a period of 14–20 years. Scholars of psychological and political change often note the rapid decay of signs of change. For example, heightened levels of posttraumatic stress disorder, anti-immigrant attitudes, and avoidance of airplane travel following 9/11 dissipated within months after the attack (14–16). Studies of decay rarely have the benefit of data collected as much as a decade before and after the external stimulus.

Second, I examined a geographic effect with more precision than other methods would permit. Studies of geographic effects often must use coarse estimates of proximity, such as effects measured inside or outside of jurisdictional boundaries. By leveraging geo-coded government data collected on nearly every individual, I was able to pinpoint a study of geographic proximity: in studying neighbors of 9/11 victims, I investigated individuals who lived on the same floor of apartment buildings or on the same block of a street as victims.

Third, by using government databases that contain records of all registered voters, I could generate a pseudocontrol group against which I could compare the behavior of affected individuals. For each 9/11 victim in New York, I searched through records of every other person in New York to identify individuals who appeared most similar to the victim. This comparison provides some leverage in estimating a causal effect of 9/11 on victims’ relations. Past studies of the 9/11 attack have failed to fully exploit the pseudoexperimental conditions surrounding the event: a large number of people were affected at the same time, by the same stimuli and—conditional on traits of these individuals that may be observable—they were affected at random. We may imagine 9/11 as a tragic experiment: of a particular population of eligible individuals, a random subset was killed. Under a set of assumptions, I could estimate how this tragedy affected the victims’ families and neighbors by studying their behaviors relative to the random subset of families and neighbors who did not experience similar loss.

Hypotheses

In exploring the political change of 9/11 families and neighbors relative to comparison groups, I examined hypotheses bearing on two dimensions: activation and directionality. The activation hypothesis is that individuals who lost someone on 9/11 will have become more politically engaged. Although 9/11 brought out a high level of civic activity among the population at large, there is a general tendency of victims of war violence and crime to engage politically, for reasons including a desire to prevent future tragedies of the kind that befell them, a psychological demand for solidarity with other victims, an increased reliance on public institutions for support, and general downstream effects of “posttraumatic growth” (e.g., refs. 9, 17, and 18). The longevity of an activation effect has not been thoroughly assessed in prior research, but I tested for change in participation up to 11 years following the attack.

The primary directional hypothesis is that close relations of 9/11 victims will have become more politically conservative following the attack. Past research indicates increases in feelings of threat, authoritarianism, and conservatism following 9/11 (4–6). [However, individuals who reported personally knowing victims were also found to have high levels of anxiety, which correlated with more dovish political preferences (5).] An alternative hypothesis of “ideological intensification” suggests that individuals engage more intensely with their preexisting political dispositions following events like 9/11, with liberals becoming more intensely liberal and conservatives becoming more intensely conservative (6, 19). Although 9/11 had no lasting perceptible effect on the policy positions or ideological dispositions of typical Americans (5), the lasting effects on victims’ families and neighbors are heretofore unexamined.

Methods

The complete details of the methodology are reviewed in the SI Text but are summarized briefly here. The research began by acquiring a list of registered voters in the state of New York that was accurate as of summer 2001. [Because all of the identifying information in this study stem from public records, the study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board review (Yale University Human Subjects Committee Protocol no. 1305011974).] The database contained personal information of all 9,995,513 New Yorkers registered at that time. Culling information from digital obituaries of 9/11 victims, I matched all 9/11 victims residing in New York to the statewide voter file (for reasons of cost and data availability, this study was restricted to 9/11 victims residing in New York at the time of the attack). Of the 1,729 victims from New York, I identified 1,181 (68%) as registered voters. This number matches the percentage of New York citizens overall who were registered to vote at the time.

For each victim, I used a combination of exact matching and Mahalanobis distance matching to identify up to five “control victims.” The variables used in the matching algorithm include demographics, prior political activities, and family and neighborhood characteristics. To be clear, the control victims, who were mostly residents of metro New York and similarly situated as the true victims, were themselves obviously affected by the events of 9/11. This only biases the study toward a null result and isolates the effect under investigation as being particular to families and neighbors of victims. The causal effect estimated here is not the general effect of the 9/11 attack, but rather the specific effect of the attacks on families and neighbors.

For each victim and “control victim,” I used information contained in the statewide voter file to identify the family members in their households who were also registered and to find their nearest residential neighbors. For victims’ families and neighbors and for the control victims’ families and neighbors, I matched their identifying information to current 2013 records of registered voters and to Federal Election Commission records of campaign contributors (20).

To test the hypotheses, I relied on four dependent variables: (i) participation in federal elections, (ii) participation in political party primaries, (iii) campaign contributions, and (iv) party affiliation. If 9/11 induced victims’ family and neighbors to be more engaged in politics, I expected increased levels of participation in general elections, party activities, and in financial contributions to politicians. An intensification of ideological commitments would also show itself in increases in party activities, such as primaries and fundraising, which tend to be dominated by more ideologically extreme citizens (21, 22). Finally, a shift to conservatism can be examined through change in party affiliation, whereby defection away from the Democratic Party and toward the Republican Party would signal a conservative shift.

Results

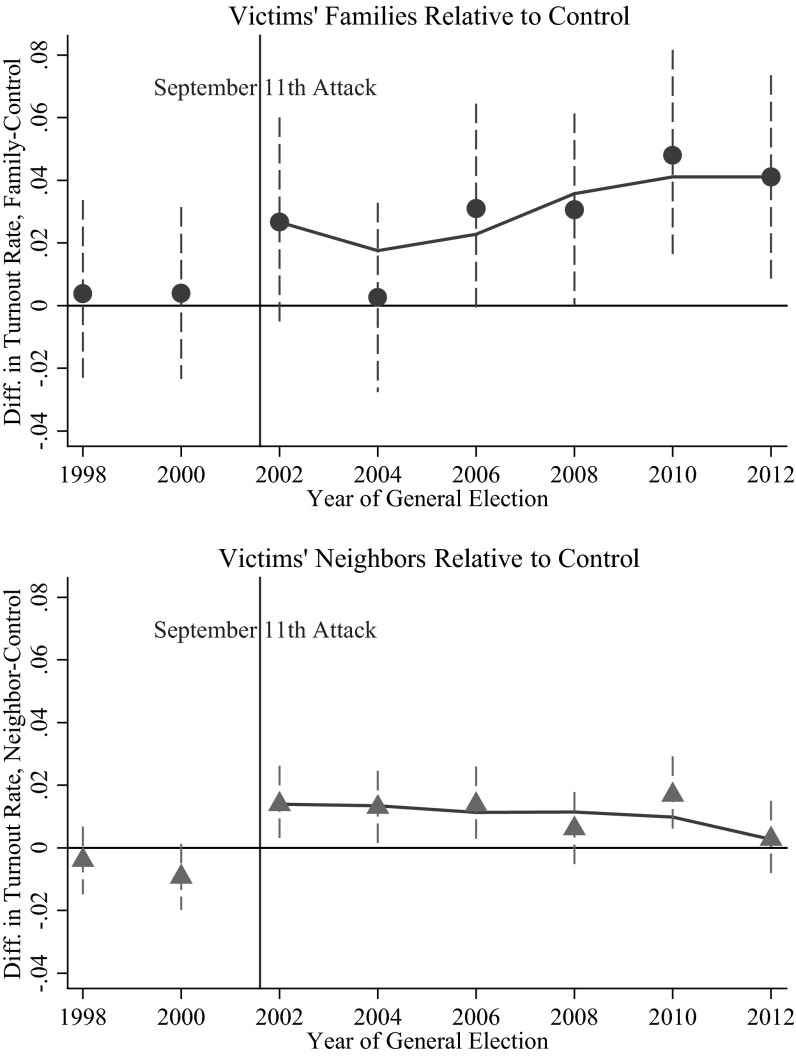

Fig. 1 shows the effect of 9/11 on the election participation of victims’ families and neighbors. Compared with their control groups, families and neighbors increased their level of participation following 9/11. On average, the effect is approximately twice as strong for families as for neighbors. Particularly important in Fig. 1 is the persistence of the effect over time. We see no decay in the effect for families of 9/11 victims and no decay among neighbors until 2012, over a decade after the attacks. Note that in this figure, and in subsequent ones, the confidence intervals for families are considerably larger than those for neighbors. This feature of the data is explained by the sample sizes being over eight-times larger for the analysis of neighbors as for the analysis of families.

Fig. 1.

The effect of 9/11 on participation in general elections among victims’ families and neighbors. Each dot represents a difference of means between treatment and control groups, shown with a 95% confidence interval. Regression-based estimates of the treatment effects, with controls and clustered SEs, are shown in SI Text. A dot at 0.04 in the upper graph can be interpreted as meaning that 9/11 families voted at a rate 4 percentage points higher than their comparison group in a particular election. Of the pre-9/11 records matched to currently or formerly registered voters in the post-9/11 file, observation counts are 6,084 for family members (treatment and control) and 48,525 for neighbors (treatment and control).

Fig. 2 shows the effect of 9/11 on campaign contributions. Similar to Fig. 1, there is a significant increase in political participation following 9/11 for families of victims. However, there is no effect for neighbors. Note that nearly all 9/11 victims’ families received a lump sum payment from the federal government after the attacks (23). How this infusion of money affected the families’ propensity to donate is unknown. Although family campaign contributions increased, as evident in Fig. 2, the proportion of contributions going to each party did not change. Note that a directional shift of donations may not reveal itself simply because the overall number of people who make political contributions is quite small; splitting the donor pool into Republican and Democratic may be stretching the data too much.

Fig. 2.

The effect of 9/11 on the rate of donations to federal political campaigns among victims’ families and neighbors. Each dot represents a difference of means between treatment and control groups, shown with a 95% confidence interval. Regression-based estimates of the treatment effects, with controls and clustered SEs, are shown in SI Text. A dot at 0.03 can be interpreted as meaning that 9/11 families donated to campaigns at a rate 3 percentage points higher than their comparison group in a particular election cycle. Of the pre-9/11 records matched to post-9/11 Federal Election Commission (FEC) donation files, observation counts are 6,742 for family members (treatment and control) and 56,757 for neighbors (treatment and control).

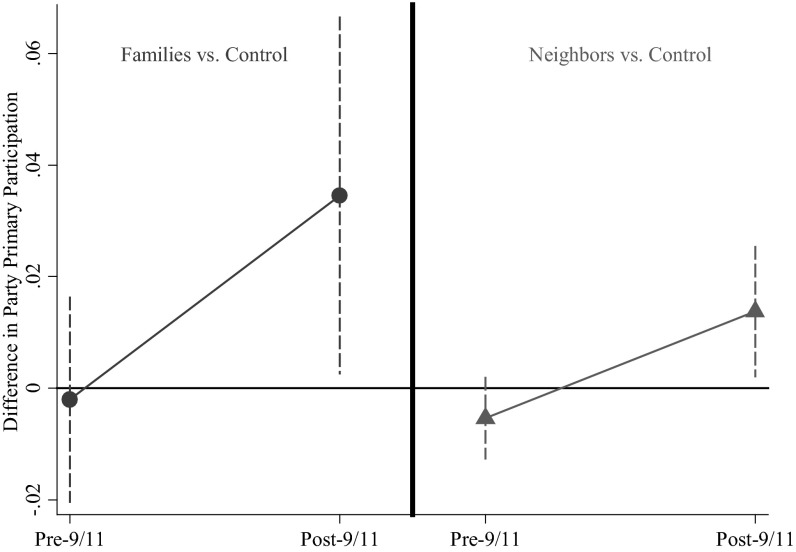

Fig. 3 summarizes the level of participation in party primaries in the years preceding and following 9/11. Families, and to a lesser extent neighbors, show significant increases in primary participation following 9/11, compared with their control groups. Although participation in primaries increased, the proportion of participants from each party did not change.

Fig. 3.

The effect of 9/11 on party primary participation among victims’ families and neighbors. Each dot represents a difference of means between treatment and control groups, shown with a 95% confidence interval. Regression-based estimates of the treatment effects, with controls and clustered SEs, are shown in SI Text. A dot at 0.04 on the left side can be interpreted as meaning that 9/11 families were 4 percentage points more likely than a control group to participate in at least one primary from 2002 to 2012. Pre-9/11 primaries include primaries from years 1998, 1999, and 2000. Post-9/11 primaries include primaries in all years 2002–2012. Of the pre-9/11 records matched to currently or formerly registered voters in the post-9/11 file, observation counts are 6,160 for family members (treatment and control) and 49,136 for neighbors (treatment and control).

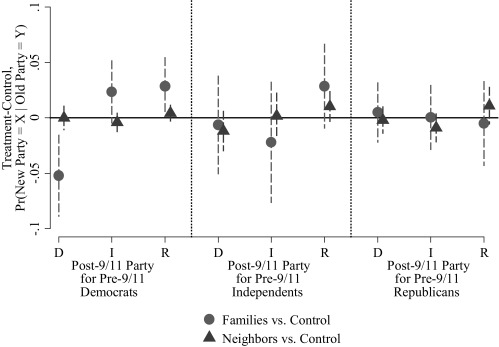

Figs. 4 and 5 show two views of party conversions. Over the course of a 12-year period, 17% of the overall sample changed their party affiliation. Note that unlike vote history, which is recorded on registration records for each election year, changes to party affiliation would be overridden from prior affiliations, thus resulting in only one post-9/11 measure of party (current as of summer 2013). Fig. 4 shows the difference between families and neighbors and their control groups in being a Republican, Democrat, or Independent, conditional on their pre-911 affiliation. The largest effects are for pre-9/11 Democrats, who are less likely to be Democrats in 2013 and more likely to be Independents or Republicans. However, other cohorts show movement, including families and neighbors who were Independents becoming slightly more Republican. In Fig. 5, I show a summary plot that focuses on shifts to the Democratic Party among pre-9/11 Republicans and Independents and shifts to the Republican Party among pre-9/11 Democrats and Independents. The figure shows that compared with their control groups, among voters who were not Republican before 9/11, families and neighbors are more likely to be Republican in 2013.

Fig. 4.

Party defection among victims’ families and neighbors. The plot shows difference of means between treatment and control groups in the probability that a voter is registered with a party post-9/11, conditional on his or her pre-9/11 party. The first dot is interpreted as meaning that among pre-9/11 Democrats, 9/11 families are 5 percentage points less likely to be registered as Democratic in 2013, relative to their control group. Regression-based estimates are shown in SI Text. Of the pre-9/11 records matched to currently or formerly registered voters in the post-9/11 file, observation counts are 6,084 for family members (treatment and control) and 48,525 for neighbors (treatment and control).

Fig. 5.

Party conversion among victims’ families and neighbors. This plot estimates shifts to Republican affiliation and Democratic affiliation among pre-9/11 non-Republicans and pre-9/11 non-Democrats. Families and neighbors who were not registered Democrats in 2001 were no more likely to become Democrats by 2013 compared with the control groups. However, families who were not Republicans before 9/11 are 3 percentage points more likely to be Republicans in 2013, compared with their control group. Regression-based estimates are shown in SI Text. Of the pre-9/11 records matched to currently or formerly registered voters in the post-9/11 file, observation counts are 6,084 for family members (treatment and control) and 48,525 for neighbors (treatment and control).

Discussion

This analysis has shown that 9/11 significantly increased political participation of the affected populations, lending support to the activation hypothesis. Families and neighbors became more involved in politicized activities, including the selection of party nominees and in providing financial support to favored candidates, consistent with an ideological intensification hypothesis. Finally, although families, and to a lesser extent neighbors, became more involved in their own parties’ activities, there was an average shift in allegiance to the Republican Party, supporting the conservative-shift hypothesis.

The changes in the political behavior of affected groups is long-lasting, with effects perceptible 12 years following the attack. The magnitude of the effects is generally on the order of a 1–5 percentage point change. In some post-9/11 election years, the differences between treatment and control groups are not significant at the standard 0.05 level. Although the effect sizes are small, remember that the treatment group is being compared against matched cases who may also have been affected by 9/11. The effect measured here is the specific effect of having a personal connection to a victim.

Although social scientists have previously found psychological and behavioral effects of terrorism and acts of violence, never before have such effects been found to be so enduring, nor have such effects been estimated with objective individual-level indicators rather than through biased self-reports or aggregated data. Nor have the effects of terrorism on victims’ relations been subjected to a pseudoexperimental design so that the effects of interest can be isolated from population-wide change. The result is a clear indication that 9/11 catalyzed long-lasting political changes among those most affected, making them more active in politics, more partisan, and more supportive of the political right.

To be sure, families and neighbors of victims might embrace the Republican Party after 9/11 for reasons others than an ideological change. At the time of the attack, the Presidency and New York mayoral office were both in Republican hands, and victims may have become more Republican because they simply supported the leadership that happened to be in power. At the same time, this finding is consistent with much other research suggesting that authoritarian and conservative feelings often follow from victimhood (4–6).

Extensions to this research endeavor may pursue the mechanisms that underlie the increases in political participation and in Republican support following 9/11. Future research may also consider answering other questions about how human behaviors are shaped by shocks, both large and small, that are suited to the method of linking government records and matching treated subjects to comparable untreated ones. To the extent that government records can be used for these purposes in other contexts, it would be particularly useful to examine how generalizable the results are here by using the same method to measure the effects of terrorist attacks in other countries and other circumstances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Yale University’s Institution for Social and Policy Studies for financial support; Adam Bonica for sharing data on campaign contributors; Peter Aronow, Matthew Blackwell, Daniel Hopkins, Eleanor Powell, Frederic Reamer, and Todd Rogers for helpful comments; and lead research assistant Michael Young (Yale University) for his careful work.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Harvard Dataverse Network.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315043110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schuster MA, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(20):1507–1512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlenger WE, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the National Study of Americans’ Reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288(5):581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford CA, Udry JR, Gleiter K, Chantala K. Reactions of young adults to September 11, 2001. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(6):572–578. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.6.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonanno GA, Jost JT. Conservative shift among high-exposure survivors of the September 11th terrorist attacks. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2006;28(4):311–323. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huddy L, Feldman S, Taber C, Lahav G. Threat, anxiety, and support of antiterrorism policies. Am J Pol Sci. 2005;49(3):593–608. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huddy L, Feldman S. Americans respond politically to 9/11: Understanding the impact of the terrorist attacks and their aftermath. Am Psychol. 2011;66(6):455–467. doi: 10.1037/a0024894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jost JT, Glaser J, Kruglanski AW, Sulloway FJ. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(3):339–375. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner FR, Jones BD. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: Univ of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateson R. Crime victimization and political participation. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2012;106(3):570–587. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasper JT, Reeves A. Make it rain? Retrospection and the attentive electorate in the context of natural disasters. Am J Pol Sci. 2011;55(2):340–355. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healy A, Malhotra N. Random events, economic losses, and retrospective voting: Implications for Democratic competence. Q J Polit Sci. 2010;5(4):193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraga B, Hersh E. Voting costs and voter turnout in competitive elections. Q J Polit Sci. 2010;5(4):339–356. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansolabehere S, Hersh E. Validation: What survey misreporting reveal about survey misreporting and the real electorate. Polit Anal. 2012;20(4):437–459. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1235–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopkins DJ. Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(1):40–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gigerenzer G. Out of the frying pan into the fire: Behavioral reactions to terrorist attacks. Risk Anal. 2006;26(2):347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laufer A, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic symptoms and posttraumatic growth among Israeli youth exposed to terror incidents. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25(4):429–447. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blattman C. From violence to voting: War and political participation in Uganda. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2009;103(3):231–247. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyszczynski T, Solomon S, Greenberg J. In the Wake of 9/11: The Psychology of Terror. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonica A. Ideology and interests in the political marketplace. Am J Pol Sci. 2013;57(2):294–311. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hersh E. Primary voters versus caucus goers and the peripheral motivations of political participation. Polit Behav. 2012;34(4):689–718. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenstone SJ, Hansen JM. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinberg KR. What is Life Worth? The Unprecedented Effort to Compensate the Victims of 9/11. New York: PublicAffairs; 2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.