Abstract

Background

Although thermal imaging can be a valuable technology in the prevention and management of diabetic foot disease, it is not yet widely used in clinical practice. Technological advancement in infrared imaging increases its application range. The aim was to explore the first steps in the applicability of high-resolution infrared thermal imaging for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease.

Methods

The plantar foot surfaces of 15 diabetes patients were imaged with an infrared camera (resolution, 1.2 mm/pixel): 5 patients had no visible signs of foot complications, 5 patients had local complications (e.g., abundant callus or neuropathic ulcer), and 5 patients had diffuse complications (e.g., Charcot foot, infected ulcer, or critical ischemia). Foot temperature was calculated as mean temperature across pixels for the whole foot and for specified regions of interest (ROIs).

Results

No differences in mean temperature >1.5 °C between the ipsilateral and the contralateral foot were found in patients without complications. In patients with local complications, mean temperatures of the ipsilateral and the contralateral foot were similar, but temperature at the ROI was >2 °C higher compared with the corresponding region in the contralateral foot and to the mean of the whole ipsilateral foot. In patients with diffuse complications, mean temperature differences of >3 °C between ipsilateral and contralateral foot were found.

Conclusions

With an algorithm based on parameters that can be captured and analyzed with a high-resolution infrared camera and a computer, it is possible to detect signs of diabetic foot disease and to discriminate between no, local, or diffuse diabetic foot complications. As such, an intelligent telemedicine monitoring system for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease is one step closer. Future studies are essential to confirm and extend these promising early findings.

Keywords: automatic detection, diabetic foot, infrared imaging, prevention, telemedicine, thermography

Introduction

Foot ulcers are a frequent and costly complication of diabetes, with a lifetime incidence of 15–25% and up to 20% of the total health care expenditure on diabetes attributable to foot ulcers.1,2 If left untreated, ulcers will become severely infected and ultimately result in amputation of the limb and/or death.2,3 Diabetic foot ulcers are preventable through the early detection and timely treatment of signs of diabetic foot disease.2 However, early detection depends on frequent assessment, which may be limited for various reasons. Self-examination can be difficult or impossible due to the health impairments related to diabetes or social impairments. Frequent (e.g. weekly) examination by health care professionals would be too intrusive and costly and is also limited because, for example, the human hand is not an objective means to assess temperature, which is a marker of underlying infammation.4 Our ultimate objective is to develop an intelligent telemedicine monitoring system that can be deployed for frequent examination of the patient’s feet to timely and automatically detect signs of diabetic foot complications.

Thermal imaging is a promising technology to achieve this objective, as increased plantar foot temperature is a key sign of underlying inflammation. Thermal imaging has been shown to be a useful technique in the clinical management of the diabetic foot.5,6 Severl diabeticic foot complications such as neuropathic ulcers,7, 8 osteomyelitis,9,10 and Charcot foot7,11 have been identified at increased temperature locations. Increased plantar foot temperature may even be present a week before a neuropathic ulcer appears.11 Clinical studies on home-monitoring of plantar foot temperature based on that finding have shown that frequent temperature assessments and immediate treatment in case of temporally persistent temperature differences (>2.2 °C) between a foot region and the same region in the contralateral foot can prevent diabetic foot ulcers.12–14 On the other hand, decreased foot temperatures may indicate vascular insufficiency in the foot.15,16 Finally, a relationship between a temperature-based wound inflammatory index and wound healing has been proposed as a robust indicator of tissue health with a quicker response time to predict healing versus wound size.17

A variety of thermal imaging techniques have been used and tested to date, of which infrared imaging and liquid crystal thermography seem to hold most promise for use in daily clinical practice.5,15,18 Compared with liquid crystal thermography, infrared imaging has the advantage of being a noninvasive measurement with possibilities for automatic analysis. As such, infrared imaging shows greater potential for telemedical applications and will be the focus of this article. The first clinical application of infrared imaging in the diabetic foot was measurement of plantar foot temperatures using a handheld thermometer as described by Lavery and coauthors12–14 in their clinical studies. Although being low cost, the disadvantages of such a thermometer are: low spatial resolution (temperature is measured on selected individual spots only), the necessity that patients perform the measurement themselves, and lack of options for automatic analysis. Furthermore, results on sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm used in these clinical studies have not been published to date. With technological advancements in infrared imaging and analysis, it is possible to overcome these limitations. The aim of this study was to explore the first steps in the applicability of high-resolution infrared thermal imaging for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease.

Methods

For this pilot study, a convenience sample of 15 patients with diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2 was obtained, equally divided over three groups: 5 patients without present signs of diabetic foot complications, 5 patients with local signs of diabetic foot complications (e.g., abundant callus or neuropathic ulcer), and 5 patients with diffuse complications (e.g., Charcot foot, infected ulcer, or critical ischemia). Screening and diagnosis for presence of signs of diabetic foot complications was done by a certified wound consultant who, in accordance with diagnostic criteria described in the international guidelines, had more than 15 years of experience in diabetic foot care, before treatment started.2 Patients were included within 2 weeks after first presentation at the outpatient clinic with their foot complications. Neuropathy was assessed with a 10 g Semmes–Weinstein monofilament and peripheral arterial disease by assessment of pedal pulses and toe pressure. Diagnosis of osteomyelitis and Charcot foot was confirmed by the findings of the radiologist on X ray and magnetic resonance imaging. Presence of critical ischemia was confirmed by Doppler toe pressure measurements <30 mm Hg. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before the measurements. All research efforts were in compliance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethical Committee Twente approved the study protocol.

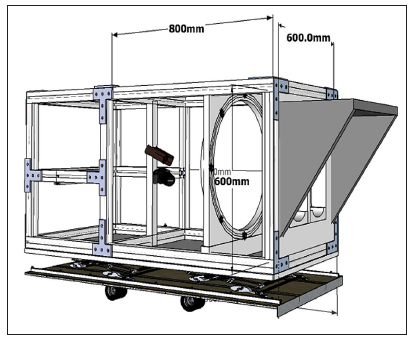

Patients were seated in supine position on a treatment bench. After shoes, socks, and (if applicable) dressings were removed, patients remained seated for a minimum of 5 min to allow equilibration of foot temperature. Pilot measurements showed no further changes in foot temperature after 5 min of rest. Patients were instructed to place their feet on support bars inside an experimental setup (Figure 1) in such a way that their shank and thigh remained supported on the treatment bench. The experimental setup comprised two cameras (one for color images, one for thermal images; specifications in Table 1), a light module, thermal reference elements, and foot supports. The light module consisted of eight LZ1–10WWW05 light-emitting diodes (LendEngin Inc.), each sized 4.4 × 4.4 mm. Thermal reference elements were six black blocks of 35 × 20 mm, with calibrated PT1000 resistor and heating resistors. The cameras, light module, and thermal references were connected to a desktop computer and a screen.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawing of the interior of the experimental setup. The feet are positioned on the support bars, below the light shield, on the right side of the image. The thermal camera and the color image camera are placed 800 mm from the foot supports, with the thermal camera above the color image camera. The light module is the ring between the cameras and the foot supports, containing eight light-emitting diodes (black dots).

Table 1.

Specifications of the Two Cameras in the Experimental Setup

| Color image camera | Thermal camera | |

| Camera type | Canon Eos 40D with EF-s 17–85 mm lens | FLIR SC305 with 16 bit resolution |

| Resolution | APS-C size (22.2 × 14.8 mm) | 320 × 240 pixels, 1.2 mm per pixel |

| Sensor | 10.5 mega pixel single plate complementary metal-oxide semiconductor sensor | |

| Angle of view | Horizontal: 68°40’–15°25’

Vertical: 48–10°25’ Diagonal: 78°30’–18°25’ |

25° × 19°; focal length 18 mm |

| Field of view | 420 × 280 mm | 420 × 315 mm |

| Thermal sensitivity | Not applicable | <0.05–30 °C |

| Objective temperature range | Not applicable | -20 to 120 °C |

| Computer interface | USB 2.0 high speed | Ethernet IEEE 802.3 |

All parts of the system apart from the desktop computer and the screen were mounted in a wooden box sized 600 × 600 × 1900 mm, with a light-shielding extension in front. Both shanks and thighs of the patient were covered with a sterile cloth. The entrance of the light-shielding extension of the box was further covered with a black cloth to eliminate any influence of ambient light conditions.

The color image camera was automatically focused during every measurement. The thermal camera was calibrated and focused at the start of each measurement day, using a plate covered with fat black spray paint that was positioned at the location of the feet, with the thermal reference elements above and beneath the plate. Calibration was performed based on the equal thermal distribution of the plate (room temperature). Additionally, temperature of the thermal reference elements was obtained during the measurements to ensure consistency of the thermal measurements during the day by comparing measured temperature values with registered temperature values of the reference elements.

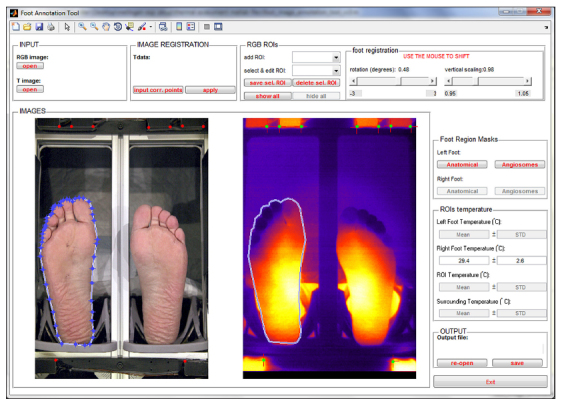

During each measurement, two images were acquired: one color image with all light sources on, followed by an infrared image with all light sources of. Both cameras were driven using custom-made MATLAB software (the Mathworks, MA). Data were processed in MATLAB. For live assessment of the patient’s feet, the wound consultant annotated specific regions of interest (ROIs) with signs of diabetic foot complications (e.g., callus, ulcer) using a paper sheet on which the foot boundaries were drawn. In the color image, both the boundaries of the foot and the ROIs were manually annotated with self-designed MATLAB software (see Figure 2). This annotation was transferred to the thermal image. From the pixels encapsulated by the boundaries of the foot as well as those encapsulated by the ROIs, the mean temperature and the standard deviation (SD) across pixels were automatically processed using MATLAB.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the manual annotation of the right foot in the color image and its subsequent transfer to the thermal image.

Results

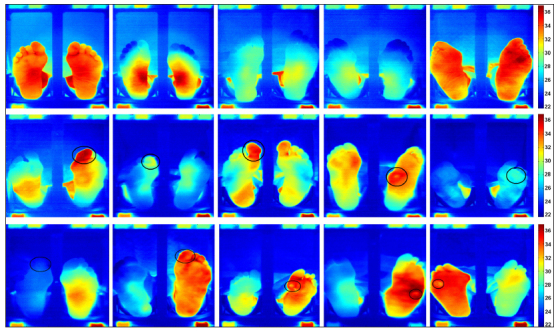

Patient characteristics and temperature results from the infrared imaging are shown in Table 2 . Mean (SD) number of pixels encapsulated by the foot boundary was 11,462 (1492); mean (SD) number of pixels encapsulated by the ROI was 82 (40). Thermal images are shown in Figure 3 for the three subgroups of patients. Differences in mean temperature between the ipsilateral and contralateral foot in patients with no or local complications were at maximum 1.5 °C. Mean temperature between ipsilateral and contralateral foot of patients with diffuse complications differed at minimum 3 °C , where feet with osteomyelitis and/or Charcot feet were warmer and those with critical ischemia were colder compared with the contralateral foot.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics and Temperature Values in Mean (SD) Degrees Celsiusa

| Patient characteristics | Temperature (°C ), mean (SD) | |||||||||||||

| # | M/F | Age | DM type | Neuropathy | PAD | Complicationsb | Foot | Ipsilateral footc | Contralateral foot | ΔT1 | ROI ipsilateral footd | ROI contralateral footd | ΔT2 | ΔT3 |

| No complications | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | M | 58 | 2 | Yes | No | – | 33.6 (1.4) | 33.6 (1.4) | 0.0 | |||||

| 2 | F | 36 | 1 | No | No | – | 29.6 (2.7) | 29.4 (2.6) | 0.2 | |||||

| 3 | M | 84 | 2 | Yes | Yes | – | 29.4 (1.8) | 29.7 (1.1) | −0.3 | |||||

| 4 | M | 79 | 2 | Yes | No | – | 28.8 (1.7) | 29.6 (1.6) | −0.8 | |||||

| 5 | M | 81 | 2 | Yes | No | – | 33.9 (1.9) | 33.8 (1.0) | 0.1 | |||||

| Local complications | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | M | 76 | 2 | Yes | No | Ulcer hallux (1A) | Left | 30.8 (2.4) | 29.3 (2.0) | 1.5 | 35.0 (0.6) | 26.2 (0.7) | 8.8 | 4.2 |

| 7 | M | 69 | 2 | Yes | Yes | Ulcer hallux (1A) | Right | 26.1 (1.4) | 26.2 (1.4) | −0.1 | 28.9 (0.6) | 24.9 (0.7) | 4.0 | 2.8 |

| 8 | M | 49 | 2 | Yes | No | Ulcer hallux (1A) | Right | 29.5 (2.0) | 29.1 (1.4) | 0.4 | 32.7 (0.9) | 31.5 (0.5) | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| 9 | M | 68 | 2 | Yes | No | Ulcer 2nd ray (1A)e | Left | 30.8 (1.5) | 30.2 (1.1) | 0.6 | 33.1 (0.3) | 30.6 (0.3) | 2.5 | 2.3 |

| 10 | F | 67 | 2 | Yes | No | Callus MTP2–4 | Left | 26.0 (1.1) | 24.9 (0.7) | 1.1 | 27.3 (0.1) | 25.0 (0.2) | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| Diffuse complications | ||||||||||||||

| 11 | M | 81 | 2 | Yes | Yes | Critical ischemia Ulcer hallux (1C) | Right | 25.1 (0.7) | 29.0 (2.0) | −3.9 | 24.0 (0.1) | 24.6 (0.1) | −0.6 | −1.1 |

| 12 | M | 71 | 2 | Yes | No | Charcot foot Ulcer hallux (1A) | Left Left | 33.6 (1.1) | 28.1 (1.4) | 5.5 | 34.1 (0.3) | 26.4 (0.3) | 7.7 | 0.5 |

| 13 | F | 84 | 2 | Yes | No | Ulcer MTP1 with osteomyelitis (3B) | Left | 30.0 (1.5) | 27.0 (1.4) | 3.0 | 31.1 (0.5) | 26.2 (0.1) | 4.9 | 1.1 |

| 14 | M | 79 | 2 | Yes | No | Charcot foot Ulcer lateral midfoot with osteomyelitis (3B) | Left Left | 32.1 (1.9) | 26.0 (1.2) | 6.1 | 33.4 (0.3) | 25.9 (0.3) | 7.5 | 1.3 |

| 15 | M | 60 | 2 | Yes | No | Ulcer MTP5 with osteomyelitis (3B) | Right | 32.3 (1.0) | 28.6 (1.0) | 3.7 | 33.0 (0.5) | 29.3 (0.3) | 3.7 | 0.7 |

#, patient number; M, male; F, female; DM, diabetes mellitus; MTP, metatarsophalangeal joint; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; ΔT1, difference between mean temperature of ipsilateral and contralateral foot; ΔT2, difference between mean temperature of ROI and corresponding contralateral ROI; ΔT3, difference between mean temperature of ROI and mean temperature of ipsilateral foot.

Between brackets: Ulcer classification according to University of Texas wound classification.

For patients without complications, left foot was defined as ipsilateral foot.

The ROIs in patients with diffuse complications were their ulcer locations.

Only one complication of patient 9 is shown. In Figure 3 it can be seen that another ROI (abundant callus on first metatarsophalangeal joint) is present on the right foot. However, as there was no contralateral metatarsophalangeal joint 1 due to amputation, this ROI is not further analyzed.

Figure 3.

Thermal images of both feet of five patients without foot complications (top row, left to right, patients 1 to 5), five patients with local foot complications (middle row, left to right, patients 6 to 10), and five patients with diffuse foot complications (bottom row, left to right, patients 11 to 15). The ROIs are roughly indicated with black circles drawn on top of the image, actual ROIs were smaller and more precisely drawn. The six blocks shown along the perimeter in each image are the thermal references blocks.

In four out of five patients with local foot complications, temperature at the ROI was >2 °C higher compared with the corresponding region in the contralateral foot, and >2 °C higher compared with the mean temperature of the ipsilateral foot. In four out of five patients with diffuse complications, temperature at the ROI was >3 °C higher compared with the corresponding region in the contralateral foot. In these patients, the temperature difference between the ROI and the mean temperature of the ipsilateral foot was <1.5 °C.

Discussion

Technological advances in infrared imaging, concerning both the speed of assessment and the spatial resolution of image pixels, have increased possibilities to quantify thermal patterns and perform automated analysis on acquired thermal images of patients’ feet.6 In the current study, we explored the first steps in the applicability of high-resolution infrared thermal imaging for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease. An algorithm was developed for detecting signs of diabetic foot disease by measuring the temperature of the plantar surface of the feet, based solely on parameters that can be captured and analyzed with an infrared camera and a computer. With this algorithm, a good distinction could be made between patients having no diabetic foot complications, local complications, or diffuse complications. Patients without complications showed only small temperature differences between feet. Patients with local complications such as a noninfected and nonischemic foot ulcer or abundant callus showed locally increased temperatures of >2 °C compared with both the contralateral foot and the average temperature of the ipsilateral foot. Patients with diffuse complications such as a foot ulcer with osteomyelitis or a Charcot foot showed an increased mean temperature of >3 °C compared with the contralateral foot. These results indicate that advanced infrared thermal imaging may be applicable as diagnostic tool for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease. This may be applied for early detection and timely management of diabetic foot complications, which could contribute to the prevention of further, more devastating consequences.

In the only clinical study known to the authors that measured foot temperature in the diabetic foot, Lavery and coauthors12–14 define a difference of 4 °F (or 2.2 °C ) between a foot region and the corresponding region in the contra-lateral foot as clinically significant. The temperature differences measured in the current study confirm this threshold as clinically relevant. However, from the results of this study, it can be seen that more advanced infrared cameras allow further specification of temperature differences between feet, where temperature difference thresholds of 2 °C apply to local complications such as neuropathic ulcers and abundant callus, and temperature difference thresholds of 3 °C apply to diffuse complications such as Charcot foot, ulcers with osteomyelitis, and critical ischemia. Further testing in larger groups of unselected patients is necessary to confirm the findings of this pilot study, to refine the classification of complications based on measured temperature differences, and to calculate diagnostic accuracy with parameters such as sensitivity and specificity.

The necessity for manual annotation of the boundaries of the foot in the color image was a limitation in this study. It is unlikely that manual annotation of foot boundaries has affected the results, as adequate accuracy could be guaranteed (Figure 2). However, automated analysis is not possible when all feet require manual annotation. We are currently working on automated image analysis similar to an already-described method.20 This method includes automated definition of foot boundaries, calculation of mean temperatures, and comparison of temperatures with contralateral regions. These developments are needed to achieve our goal of an intelligent telemedicine monitoring system based on infrared imaging. Inclusion in this study was limited to patients either with or without existing pathologies. Future studies should follow patients without existing pathologies over time to investigate the diagnostic accuracy of the system in detecting diabetic foot complications as early as possible. Another limitation was the rather rudimentary differentiation in “no,” “local,” and “diffuse” complications. The local complications “neuropathic ulcer” and “abundant callus” have a different clinical significance, and therefore different referral times, but these signs could not be separated from the thermal images obtained in this study. Future studies need to explore if further differentiation is possible between these signs of diabetic foot disease based on thermal images.

Infrared temperature measurements have some limitations when applied for clinical purposes, which have been described earlier.5,21 The first is the detection of local complications that are bilaterally present in the same foot region at the same time. This is visible, for example, in patient 8, who had an ulcer with local temperature increase at the right hallux but also increased temperature at the left hallux. As a result, the temperature difference between these regions did not exceed 2 °C . As shown in this study, this limitation can be overcome with further optimization of the algorithms based on the comparison of temperature at the ROI with the mean ipsilateral foot temperature. The second limitation is the detection of diffuse complications present in both feet at the same time. Patient 5 had temperature values in both feet that are higher compared with the values measured in other patients. Based on the infrared image only, it is not possible to confirm whether this patient has bilaterally Charcot feet, bilaterally osteomyelitis, or just a pair of warm feet (e.g., due to the presence of autonomic neuropathy). By combining infrared imaging with, for example, photographic imaging, this limitation may be overcome, although it must be noted that the chances of having such severe complications on both feet at the same time are very low. Finally, the value of using absolute foot temperature values for the detection of signs of foot disease is still not clear. Foot temperatures may vary from person to person as a result of age- and sex-related differences, presence of autonomic neuropathy or peripheral vascular disease, and environmental factors such as ambient temperature.5 Properly controlled studies with advanced infrared imaging in large groups of participants are needed to determine the (additional) value of absolute foot temperature values for diagnostic purposes. Such studies preferably conduct measurements over time within patients to determine intraindividual temperature patterns and changes.

An intelligent telemedicine monitoring system as envisioned in our project is not yet close to being used in daily clinical practice. Technological issues need to be resolved, including patient positioning, camera positioning, the need for adding other imaging modalities, and automated image registration and analysis.6 Feasibility studies are needed to establish the most optimal requirements for such a system and the most effective application in daily life. Subsequently, the (cost) effectiveness of using such a system for the prevention of diabetic foot disease will have to be assessed. Prices of advanced thermal imaging systems are dropping, but it is not clear whether prices are low enough to implement such a system as a monitoring tool.

Conclusions

In this study, we explored the first steps in the applicability of infrared thermal imaging for noninvasive automated detection of signs of diabetic foot disease. We have found an algorithm that can detect signs of diabetic foot disease and discriminate between no, local, or diffuse diabetic foot complications. This algorithm is based solely on parameters that can be captured and analyzed with an infrared camera and a computer. As such, an intelligent telemedicine monitoring system is one step closer. Future studies are essential to confirm and extend these promising early findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Marvin Klein and Tim Op’t Root, Demcon Advanced Mechatronics b.v., Enschede, for their assistance in calibrating the thermal camera and the thermal references and Geert Jan Laanstra, University of Twente, for his assistance in building the experimental setup.

Glossary

- (ROI)

region of interest

- (SD)

standard deviation

Funding

This project is supported by public funding from Zon-MW, the Dutch Organisation for Health Research and Development (project ID 40–00812–98–09031).

References

- 1.Boulton AJ, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1719–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67698-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker K, Apelqvist J, Schaper NC International Working Group on Diabetic Foot Editorial Board. Practical guidelines on the management and prevention of the diabetic foot 2011. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):225–231. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lepäntalo M, Apelqvist J, Setacci C, Ricco JB, de Donato G, Becker F, Robert-Ebadi H, Cao P, Eckstein HH, De Rango P, Diehm N, Schmidli J, Teraa M, Moll FL, Dick F, Davies AH. Chapter V: diabetic foot. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42(Suppl 2):S60–S74. doi: 10.1016/S1078-5884(11)60012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murf RT, Armstrong DG, Lanctot D, Lavery LA, Athanasiou KA. How effective is manual palpation in detecting subtle temperature differences? Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1998;15(1):151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bharara M, Cobb JE, Claremont DJ. Thermography and thermometry in the assessment of diabetic neuropathic foot: a case for furthering the role of thermal techniques. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2006;5(4):250–260. doi: 10.1177/1534734606293481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharara M, Schoess J, Armstrong DG. Coming events cast their shadows before: detecting inflammation in the acute diabetic foot and the foot in remission. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):15–20. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Liswood PJ, Todd WF, Tredwell JA. Infrared dermal thermometry for the high-risk diabetic foot. Phys Ther. 1997;77(2):169–177. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Monitoring neuropathic ulcer healing with infrared dermal thermometry. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;35(4):335–373. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(96)80083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harding JR, Wertheim DF, Williams RJ, Melhuish JM, Banerjee D, Harding KG. Infrared imaging in diabetic foot ulceration. Proc 20th Annual Int Conf IEEE Engineering Med Biol Soc. 1998;20:916–918. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oe M, Yotsu RR, Sanada H, Nagase T, Tamaki T. Thermographic findings in a case of type 2 diabetes with foot ulcer and osteomyelitis. J Wound Care. 2012;21(6):274, 276–278. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.6.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Monitoring healing of acute Charcot’s arthropathy with infrared dermal thermometry. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1997;34(3):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavery LA, Higgins KR, Lanctot DR, Constantinides GP, Zamorano RG, Armstrong DG, Athanasiou KA, Agrawal CM. Home monitoring of foot skin temperatures to prevent ulceration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2642–2647. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong DG, Holtz-Neiderer K, Wendel C, Mohler MJ, Kimbriel HR, Lavery LA. Skin temperature monitoring reduces the risk for diabetic foot ulceration in high-risk patients. Am J Med. 2007;120(12):1042–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavery LA, Higgins KR, Lanctot DR, Constantinides GP, Zamorano RG, Athanasiou KA, Armstrong DG, Agrawal CM. Preventing diabetic foot ulcer recurrence in high-risk patients: use of temperature monitoring as a self-assessment tool. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(1):14–20. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ring F. Thermal imaging today and its relevance to diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(4):857–862. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagase T, Sanada H, Takehara K, Oe M, Iizaka S, Ohashi Y, Oba M, Kadowaki T, Nakagami G. Variations of plantar thermographic patterns in normal controls and non-ulcer diabetic patients: novel classification using angiosome concept. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(7):860–866. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharara M, Schoess J, Nouvong A, Armstrong DG. Wound inflammatory index: a “proof of concept” study to assess wound healing trajectory. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2010;4(4):773–779. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roback K. An overview of temperature monitoring devices for early detection of diabetic foot disorders. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7(5):711–718. doi: 10.1586/erd.10.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Harkless LB. Validation of a diabetic wound classifcation system. the contribution of depth, infection, and ischemia to risk of amputation. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(5):855–859. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaabouch N, Hu WC, Chen Y, Anderson JW, Ames F, Paulson R. Predicting neuropathic ulceration: analysis of static temperature distributions in thermal images. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15(6):061715. doi: 10.1117/1.3524233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Predicting neuropathic ulceration with infrared dermal thermometry. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1997;87(7):336–337. doi: 10.7547/87507315-87-7-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]