Abstract

The apicomplexan parasite Theileria annulata is the only intracellular eukaryote that is known to induce the proliferation of mammalian cells. However, as the parasite undergoes stage differentiation, host cell proliferation is inhibited, and the leukocyte is eventually destroyed. We have isolated a parasite gene (SuAT1) encoding an AT hook DNA binding polypeptide that has a predicted signal peptide, PEST motifs, nuclear localization signals, and domains which indicate interaction with regulatory components of the higher eukaryotic cell cycle. The polypeptide is localized to the nuclei of macroschizont-infected cells and was detected at significant levels in cells that were undergoing parasite stage differentiation. Transfection of an uninfected transformed bovine macrophage cell line, BoMac, demonstrated that SuAT1 can modulate cellular morphology and alter the expression pattern of a cytoskeletal polypeptide in a manner similar to that found during the infection of leukocytes by the parasite. Our findings indicate that Theileria parasite molecules that are transported to the leukocyte nucleus have the potential to modulate the phenotype of infected cells.

Intracellular parasites within the phylum Apicomplexa (e.g., Babesia, Eimeria, Plasmodium, Theileria, and Toxoplasma spp.) include some of the most important pathogens of humans and domesticated animals. To establish and survive, intracellular parasites modulate the host cell environment (42). Evidence that this process involves interfering with the molecular pathways that determine the phenotypes of mammalian cells is accumulating, and apicomplexan parasites have been shown to alter the control of cellular differentiation (29), proliferation (12), and apoptosis (21).

Theileria annulata and Theileria parva are tick-borne apicomplexans that cause fatal and debilitating diseases of cattle throughout large areas of Africa and Asia. A primary factor in the pathology of these diseases is the generation of neoplasia by rapidly dividing transformed infected leukocytes (6). Host cell division and dedifferentiation are induced by the intracellular multinucleated macroschizont stage (18, 29) and are accompanied by alterations to bovine gene expression (30). These events are dependent on a viable macroschizont, as they can be reversed by the treatment of cells with the theileriacidal drug buparvaquone (22). Interestingly, macroschizont-dependent alterations include molecules that are involved in controlling proliferation or that protect against apoptosis (8, 12, 26). In contrast to what occurs in the macroschizont-infected cell, proliferation of the infected leukocyte slows down and then stops during differentiation to the next parasite life cycle stage, the merozoite stage. An enlargement of the macroschizont accompanies the reduced level of leukocyte division and is followed by the production of multiple uninucleated merozoites (32). Merozoites are then released as the host cell ruptures and invade erythrocytes to form the intracellular piroplasm stages infective for the tick vector (23).

Theileria molecules that can modulate the phenotype of the host cell have not been identified, and the mechanism that down-regulates leukocyte division during differentiation to the merozoite is unknown. Parasite polypeptides (TashATs) that have the potential to modulate bovine gene expression have been described previously. The TashAT polypeptides possess domains required for binding to AT-rich DNA (AT hooks) and for transportation to the host cell nucleus (signal peptide plus AT hooks), and experimental evidence for both of these functions has been reported (37, 38). In addition, the down-regulation of TashAT gene expression during parasite differentiation is coincident with the initial reduction of leukocyte proliferation in vitro, and mammalian AT hook-containing proteins are known to be associated with the generation of neoplasia (4). From these results, it can be postulated that following the removal of TashAT expression, or an undefined macroschizont-encoded signal, host cell division slows down and eventually ceases. However, in this process, it is also possible to propose a more complicated mechanism involving parasite molecules that are required to maintain or alter the modulation of the host cell phenotype during differentiation to the merozoite. The present study has characterized a gene encoding a predicted protein with a signal peptide, DNA binding domains, a PEST region, and motifs that allow interaction with regulatory components of the higher eukaryotic cell cycle. We present evidence that the Theileria polypeptide is localized to host nuclei at significant levels in cells that are undergoing parasite differentiation and that it has the ability to modulate the phenotype of an immortalized bovine macrophage cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and nuclear extract preparation.

The cloned T. annulata-infected cell line D7, the uninfected bovine lymphosarcoma line, and its Theileria-infected counterpart were maintained in culture at 37°C as previously described (37). The D7 cell line was induced to differentiate to merozoites by being cultured at 41°C (32). Nuclear fractions were obtained by using standard methods (37). Host- and parasite-enriched nuclear pellets were resuspended in 1 ml and 250 μl, respectively, of buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol) and lysed following the addition of an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer, and the DNA was sheared by passage through a 25-gauge needle or extracted by incubation in 300 mM NaCl as previously described (33). The transformed bovine macrophage cell line BoMac was cultured at 37°C as described previously (36).

Cloning and characterization of the SuAT1 gene.

A clone representing a 2,236-bp fragment of SuAT1 was isolated from a λgt11 expression library representing parasite-enriched genomic DNA isolated from the infected D7 cloned cell line. The library was screened with a radiolabeled double-stranded concatenated CAT1 probe as previously described (38). The λgt11 insert was PCR amplified, subcloned, and sequenced with a Licor 4000 automated sequencer. DNA and protein analyses were performed by using the Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis package (11). The 2,236-bp fragment contained a contiguous open reading frame (ORF) of 1,620 bp but lacked the 5′ end of the putative polypeptide. To obtain the missing residues, a cDNA clone was isolated from a λZAP library (Stratagene) representing mRNA isolated from the piroplasm stage of T. annulata (Ankara stock). The resulting sequence of the 5′ end of the cDNA showed high identity to the genomic clone (98% in a 387-bp overlap) and contained the putative methionine start codon plus untranslated sequence. T. annulata can display significant sequence diversity, and the Ankara stock is known to contain a number of parasite genotypes (15); therefore, a 322-bp fragment spanning the 5′ end of the ORF was PCR amplified from cell line D7 genomic DNA by using Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Sequence analysis revealed two nucleotide alterations relative to the cDNA sequence, one of which resulted in the substitution of a P for an H at residue 7 of the putative polypeptide. Two possible PCR errors were also detected in the ORF of the genomic contig; these errors were corrected after a comparison with the cDNA sequence was made, and additional clones were PCR amplified from D7 genomic DNA. Sequence identity searches were performed by using BLAST (2). In addition, the following programs were utilized to search for specific peptide motifs: PEST-FIND (28), predictNLS (10), and SignalP (25). For isolation of nucleic acids, Southern and Northern blotting were performed as outlined previously (34).

Preliminary genomic and/or cDNA sequence data were accessed via http://ToxoDB.org, http://www.tigr.org/tdb/t_gondii/, and http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/T_annulata/.

Antisera production, immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting.

To generate a recombinant fusion protein, a 2.2-kb genomic fragment of SuAT1, representing amino acids 19 to 558, was isolated by digestion with EcoRI and inserted into the pGEX5X-1 expression vector (Pharmacia). Expression and purification of fusion proteins were carried out on a glutathione-Sepharose column according to the protocol recommended by the manufacturer (Pharmacia) except that the sonication supernatant was diluted at a 1:2 ratio in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the fusion protein was bound to the column overnight at 4°C. The column was then washed with PBS, and the protein was eluted with elution buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. Rabbit antisera were raised against the fusion protein commercially (Diagnostics Scotland). Immunofluorescence assays were performed as outlined previously (32), but the fixation of cells was carried out as follows. Cell monolayers or cytospin slides (34) of cells cultured in suspension were immediately fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS, pH 7.4, for 30 min, followed by washing (three times) in PBS. Cells were then placed in methanol (prechilled to −20°C) for 5 min and washed (twice) in PBS. The anti-SuAT1 and anti-Oct2 sera were used at a 1:400 dilution, and the anti-Tams1 monoclonal antibody (MAb; 5E1) was used as an undiluted hybridoma culture supernatant. Immunofluorescence images were obtained with an Olympus BX60 microscope and a SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.). SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and blot development were performed as previously described (34, 38). Cell extracts were prepared, as previously described (34), from 107 cells. Cells were pelleted at 300 × g, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS and an equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were passed through a 25-gauge needle 10 times to shear DNA, boiled for 10 min, allowed to cool to room temperature, and microcentrifuged for 10 min (12,000 × g). Equal volumes of extract were loaded on to SDS-PAGE gels, and following Coomassie blue staining of these sample gels, adjustments were made to the sample volumes to give equal track loadings of protein. For nuclear extracts, the protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford assay (5a), and equal concentrations (30 μg) were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels. The following antisera were used in immunoblot analysis: anti-α-actinin (sc-7453, 1:200), anti-NF-κΒ p65 (sc-7151, 1:500), anti-Oct-2 (sc-233, 1:200), antipan cytokeratin (sc-15367, 1:200), and antivimentin (sc-7558, 1:200) (all from Santa Cruz); MAb against actin (A4700, 1:1,000) and MAb antityrosine tubulin (T9028, 1:1,000) (both from Sigma); and anti-p53 (NCL-p53-CMI, 1:5,000; Novocastra Laboratories, Ltd.). Anti-SuAT1 was used at a 1:400, anti-T. annulata ribonucleotide reductase was used at a 1:500, and MAb 5E1 was used as an undiluted culture supernatant.

Establishment and characterization of a SuAT1-transfected BoMac cell line.

Work on the TashAT cluster genes has shown that increased expression in BoMac cells was obtained by use of a modified vector (pls11) that was generated by removing the cytomegalovirus immediate early promoter region of the pIREShyg2 vector (Clontech) and replacing it with cytomegalovirus immediate early enhancer, chicken β-actin promoter, and synthetic intron of the pCX-EGFP vector (39). This vector was used to ensure the expression of SuAT1 at high levels since it can produce a single RNA transcript representing the inserted gene of interest linked to an internal ribosomal entry sequence and Hygr mRNA. The SuAT1 coding region (amino acids 32 to 558) minus the predicted signal peptide was PCR amplified with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase and the primers SATE1 (5′-GCGAGCTAGCCACCATGGATAGTAACTCTGTTTTGGAGGTT-3′), containing an NheI site and the Kozak consensus sequence, and SATE2 (5′-ACTGGATCCTACAGATCCTCTTCAGAGATGAGTTTCTGCTCATTGTCATCTTTAGATTTCTCTTC-3′), containing a BamHI site. The PCR fragment was then digested with NheI and BamHI, gel purified, and ligated into the NheI and BamHI sites of pls11. The insertion of the resulting pls11-SuAT1 construct was confirmed for fidelity by sequencing.

Stable transfection of BoMac cells was carried out by using SuperFect transfection reagent (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Hygromycin (200 μg ml−1) was then added to the cultures 48 h later to select for stable transfectants. A confluent culture was obtained for cells transfected with the control vector pls11 within 18 days. In contrast, the pls11-SuAT1 cells took longer to establish a permanent line and appeared to be derived from a single cluster of cells. All nontransfected control cultures failed to establish a permanent line. To estimate cell numbers, test and control cultures were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells per flask (four replicates) and incubated for 5 to 6 days in the presence or absence of hygromycin. Cells were harvested and resuspended in RPMI medium, and viable cells were counted by use of trypan blue exclusion and a hemocytometer. The differences between means were tested by t distribution analysis. Culture morphology was assessed by paraformaldehyde fixation and phase-contrast microscopy. For drug-free cultures, experiments were performed at least 4 weeks after the removal of hygromycin.

Nanospray tandem mass spectrometry and database searching.

Bands of interest were excised from Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels and subjected to in-gel trypsin (Promega, Madison, Wis.) digestion overnight at 37°C by using a previously described method (19). Digestion products were desalted by using C18 ZipTips (Millipore, Billerica, Mass.) prior to analysis with the QSTAR Pulsar tandem mass spectrometer running in the positive ion mode and the Analyst QS software package (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) in conjunction with Proxeon (Odense, Denmark) nanospray capillaries. Data were collected from 400- to 1,200-Da proteins, and peaks were selected for mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry by using an IDA filter. The mass spectrometry-mass spectrometry data were searched against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database with the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence reported here has been submitted to the DDJB/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession number AJ605117.

RESULTS

Isolation and sequence analysis of the SuAT1 gene.

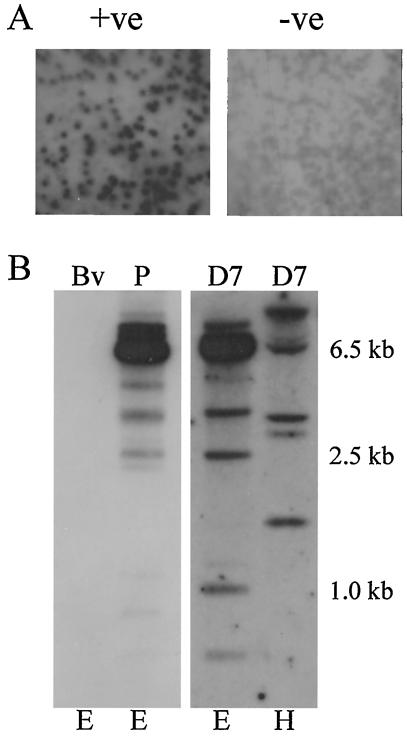

Previous studies indicated that the decision to undergo parasite differentiation involves a quantitative increase in DNA binding factors that control merozoite gene expression (35), and a parasite nucleotide motif (CAT1) that specifically binds Theileria nuclear factors has been identified (33). To characterize polypeptides with the potential to bind to this motif, a genomic λgt11 expression library was screened with a concatenated double-stranded CAT1 probe. The screen resulted in the isolation of a single λgt11 clone (SuAT1) that showed significant binding to the DNA probe (Fig. 1A). Southern blotting was performed on DNA derived from an infected cloned cell line and genomic bovine DNA by using an EcoRI fragment of the SuAT1 gene as a probe. A major 6.5-kb EcoRI fragment was specifically detected in parasite-derived DNA, and, as additional bands were also identified under both reduced- and high-stringency conditions (Fig. 1B), it was concluded that additional genes related to SuAT1 are carried within the T. annulata genome. This result has been confirmed by the identification of a further two genes closely related to SuAT1 within the T. annulata genomic database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/T_annulata/blast_server.shtml). No signal was obtained with bovine genomic DNA. Additional bands were also obtained by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1C), as the SuAT1 probe detected two mRNA species of 2.2 and 4.4 kb. The 2.2-kb species was detected in RNA derived from macroschizont-infected cells (day 0) and in RNA isolated from differentiating parasites (day 7), while the 4.0-kb species was detected only in RNA isolated from a differentiating culture.

FIG. 1.

DNA binding, Southern blot, and Northern blot analyses of SuAT1. (A) Binding of the concatenated CAT1 probe to a third-round λgt11 pick expressing SuAT1 (+ve) and a negative control pick (−ve); (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic bovine DNA (Bv), T. annulata (Ankara) piroplasm DNA (P), and infected cloned cell line D7, representing a single parasite haploid-genome (D7) DNA digested with EcoRI (E) or HindIII (H); (C) Northern blot of RNA derived from uninfected BL20 cells (BL) and a differentiation time course of the D7 cell line at day 0 (37°C), day 4 (41°C), and day 7 (41°C). Blots were hybridized with a 2.2-kb EcoRI genomic DNA SuAT1 probe and a probe representing the T. annulata large-subunit rRNA gene (38).

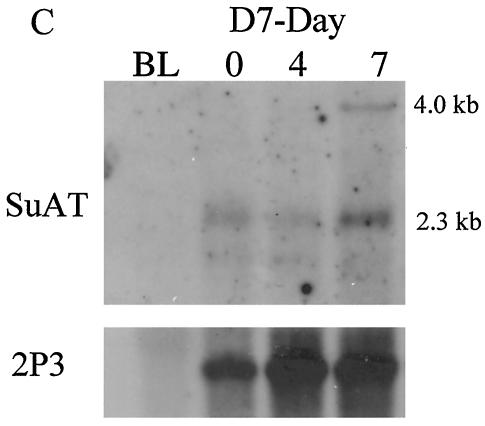

The sequence of the complete ORF of SuAT1 was found to be uninterrupted by introns and encoded 558 amino acids (Fig. 2A). A comparison of the SuAT1 sequence with the NCBI protein databases showed relatedness to the TashAT and Tash1 polypeptides of T. annulata (38, 40). Of particular interest was the conservation of a number of previously identified motifs that predict a DNA binding function and/or nuclear localization. Thus, the SuAT1 sequence contained an AT hook motif (Fig. 2B) with an RGRP core that was identical to AT hook domains previously identified for the TashAT proteins and highly related to the AT hooks of the HMGIY polypeptide (38). In addition, the regions that flank the consensus AT hook and align with the first and third AT hooks of TashAT2 and TashAT1-3 are also rich in basic amino acid residues and may bind DNA. The SuAT1 sequence also encoded three potential nuclear localization signals, one of which is a bipartite nuclear localization signal encompassing the AT hook. A further potential bipartite nuclear localization signal was identified at positions 151 to 169. This motif has been found to be part of the DNA binding domain of a number of proteins, including the HMG box of ROX1 (5), and was predicted to bind to DNA (10).

FIG. 2.

Identification of SuAT1 peptide motifs. (A) Predicted amino acid sequence of SuAT1. The putative signal sequence is in boldface italics, the conserved AT hook DNA binding domain is in boldface, and the three potential nuclear localization signals are underlined. (B) Comparison of the AT hook region of SuAT1 with those of TashAT2, TashAT1 and TashAT3 (TashAT1/3; regions 1 to 3), and the HMGI(Y) protein. The conserved AT hook motif is shown in boldface, and nuclear localization signals are in italics. (C) Comparison of potential SuAT1 cyclin A docking sites with related motifs of Tash1 and TashAT2 and the cell cycle polypeptides E2F1, p21cip, cdc25a, cdc6, and pRB. (D and E) Comparisons of CDK phosphorylation sites (D) and a repeated region of unknown function (E) with related motifs of Tash1, TashAT1, TashAT2, TashAT3, and TashAT1-TashAT3 (TashAT1/3).

Other motifs with predicted functions were identified in the SuAT1 sequence. These motifs included an N-terminal signal peptide with a predicted cleavage site between residues 23 and 24. Interestingly, an RXL cyclin interaction site (16) and a (ST)PX(KRX) CDK phosphorylation site (24) were also identified and shown to be conserved across the SuAT1 and TashAT genes (Fig. 2C and D). A sequence domain identified as a small repeated region conserved between Tash1 and the TashATs was also predicted for SuAT1 (Fig. 2E) and was found to be part of two potential PEST sequences located at positions 343 to 368 and 491 to 519 (PEST-FIND scores of 14.34 and 8.31, respectively). PEST motifs act as a signal for proteolytic degradation and are found in a number of functionally important cellular polypeptides (28).

SuAT1 is localized to the host cell nucleus during parasite differentiation.

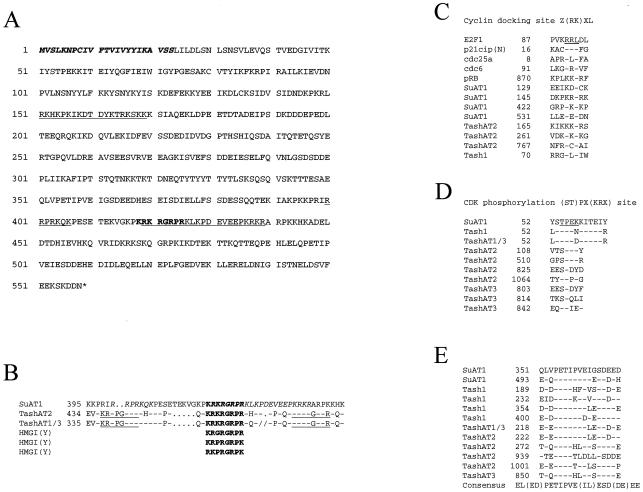

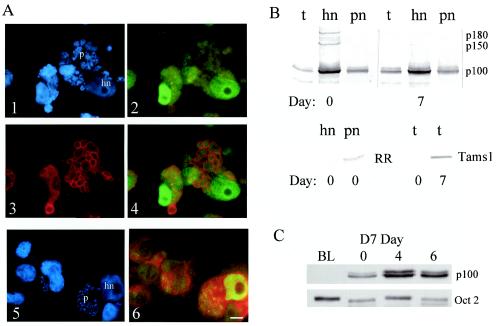

The possession of a predicted signal sequence and nuclear localization allow the postulation that the SuAT1-encoded polypeptide is transported to the host cell nucleus. To test this theory, immunofluorescence analysis was performed on Theileria-infected cells. The results showed that antiserum against the recombinant SuAT1 polypeptide clearly detected both the parasite and host nuclei of macroschizont-infected cells, compared to the reactivity obtained with preimmune serum and uninfected BL20 bovine lymphoblastoid cells (Fig. 3, panels 1 to 3). Moreover, reactivity against the host cell nuclei was detected at elevated levels in cells of cultures placed at 41°C for both 4 and 7 days (Fig. 3, panels 4 to 6) relative to an antibody against the Oct-2 transcription factor that showed constitutive levels of reactivity at these time points (Fig. 3, panels 7 to 9). As the day 7 time point has been shown to be associated with a cessation of host cell proliferation (32) and the production of merozoites, it was concluded that the SuAT1 polypeptide is present in the host nuclei of cells undergoing merogony. This result was confirmed by triple-labeling experiments carried out with anti-SuAT1, a MAb specific for the merozoite surface antigen Tams1, and DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) labeling of host and parasite nuclei. Strong host nuclear reactivity was clearly detected in cells containing parasites that were undergoing merozoite nuclear production and expressing a high level of the major merozoite surface antigen (Fig. 4A, panels 1 to 4). Double labeling with anti-SuAT1 and DAPI of nondifferentiating macroschizont-infected cells was also performed and showed that occasional cells which possessed a level of host nuclear reactivity that was higher than that of the majority of the culture tended to contain enlarged parasites (Fig. 4A, panels 5 and 6).

FIG. 3.

Immunofluorescence reactivity of anti-SuAT1 serum is elevated against differentiating Theileria-infected cells. Shown are results with preimmune rabbit serum against the D7 cells cultured at 37°C (panel 1), anti-SuAT1 serum against BL20 cells (panel 2) and Theileria-infected BL20 cells (panel 3) cultured at 37°C, anti-SuAT1 against the D7 cell line cultured at 37°C (panel 4) and at 41°C for 4 days (panel 5) and 7 days (panel 6), and anti-Oct-2 against the D7 cell line cultured at 37°C (panel 7) and at 41°C for 4 days (panel 8) and 7 days (panel 9). Exposures for different time points were matched. The background red color of the cells under IB excitation is due to counterstaining of the cells with 0.1% Evans blue. Bar = 22 μm.

FIG. 4.

Anti-SuAT1 serum detects a 100-kDa polypeptide in the host nuclei of cells undergoing merozoite production. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis. Panel 1, host cell and parasite nuclei of infected cells undergoing differentiation (day 7, 41°C) were detected by incorporation and fluorescence (blue) of DAPI; panel 2, anti-SuAT1 reactivity against day 7 cells with anti-rabbit fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate (green); panel 3, anti-Tams1 (MAb 5E1) reactivity against day 7 cells with an anti-mouse Texas red conjugate (red); panel 4, merge of green (panel 2) and red (panel 3) images; panel 5, DAPI fluorescence of nondifferentiating cells; panel 6, anti-SuAT1 reactivity against nondifferentiating (37°C) cells. hn, host cell nucleus; p, parasite. Bar = 10 μm. (B) Immunoblot analysis of total protein (t), host (hn)-, and parasite (pn)-enriched nuclear extracts that reacted with antibody against SuAT1 (p100), T. annulata ribonucleotide reductase (RR), or Tams1. Day 0, nondifferentiating macroschizont-infected D7 cells; day 7, infected D7 cells undergoing differentiation to the merozoite. (C) Immunoblot analysis of an uninfected BL20 cell nuclear extract (BL) and host-enriched nuclear extracts of D7 cells cultured at 37°C (day 0) or 41°C (days 4 and 6) with antibody against SuAT1 or Oct-2.

Immunoblotting experiments (Fig. 4B) with the SuAT1 antiserum specifically detected a molecule in total, host nuclear, and parasite-enriched nuclear extracts of infected cells that was virtually identical in mass (100 kDa) to the polypeptide detected in nuclear extracts of mammalian BoMac cells stably transfected with a SuAT1 expression construct (Fig. 5D). The level of the 100-kDa SuAT1 polypeptide was enriched in host nuclear extracts derived from macroschizont-infected (37°C) cultures and cells undergoing differentiation towards the merozoite. This pattern of localization was in contrast to those of two larger polypeptides that were detected at reduced levels in the host nuclear extract of a differentiating culture, which from their estimated masses (150 and 180 kDa) may represent cross-recognition of TashAT2 and TashAT3. A blot was also probed with an antiserum raised against the large subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (T. annulata) that specifically reacts to the parasite nucleus by immunofluorescence (39), and only a limited level of contamination of the host nuclear fraction was detected. To verify the immunofluorescent test result that indicated elevated SuAT1 levels in the host nuclei of cells undergoing differentiation to merozoites, immunoblotting was performed on host nuclear extracts derived from day 0, 4, and 6 cultures. Relative to those of the Oct-2 nuclear antigen, the levels of SuAT1 detected were greater in the extracts derived from the day 4 and 6 cultures than those detected in the day 0 extract (Fig. 4C). A minor band that migrated just above the main 100-kDa band was also detected. The lack of this doublet in transfected cells (Fig. 5D) and the detection of a band in an identical position with antisera against another SuAT-related recombinant polypeptide (B. R. Shiels and S. McKellar, unpublished data) indicate that the presence of the upper band is likely to be due to the recognition of a SuAT1-related polypeptide. Based on the immunofluorescence and immunoblot analyses, we concluded that the SuAT1 polypeptide is present at significant levels in the host nuclei of macroschizont-infected cells and cells that are undergoing differentiation into merozoites.

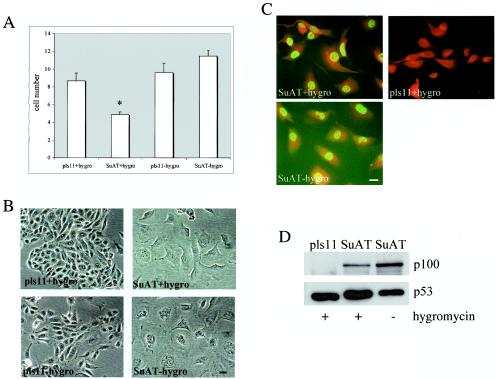

FIG. 5.

Transfection of BoMac cells with the pls11-SuAT1 construct. (A) Mean cell number (104) of BoMac cells transfected with pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 constructs cultured in the presence (+hygro) or absence (−hygro) of hygromycin. An asterisk denotes a significant difference between results for SuAT+hygro and pls11+hygro (P < 0.05). (B) Phase-contrast microscopy of BoMac cells transfected with pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 cultured in the presence or absence of hygromycin. Bar = 32 μm. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of anti-SuAT1 reactivity against BoMac cells transfected with pls11-SuAT1 or pls11 cultured in the presence or absence of hygromycin. Bar = 18 μm. (D) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear extracts of BoMac cells transfected with the pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 constructs cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of hygromycin.

SuAT1 modulates the phenotype of BoMac cells.

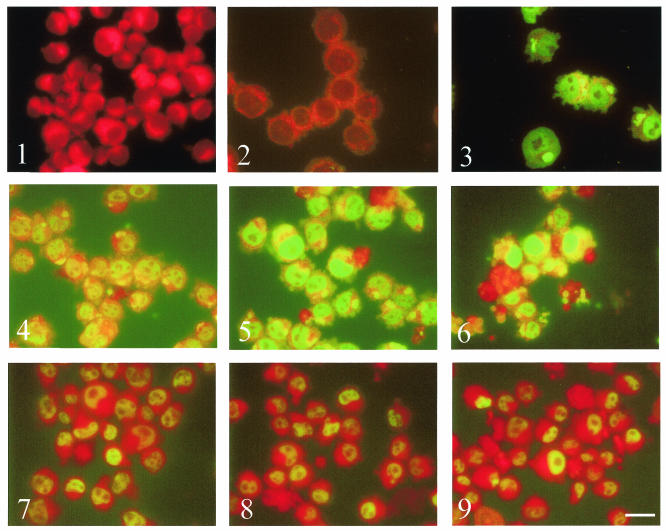

The experimental evidence outlined above, combined with the identification of sequence domains that predict modulation of gene expression and possible interaction with regulatory complexes that control the cell cycle, led us to postulate that SuAT1 may be required for parasite-mediated control of the host cell phenotype. In vivo, T. annulata is thought to readily infect cells of the macrophage lineage (14). Therefore, to examine the effect of SuAT1 on this cell type and to determine if the sequence encodes functional mammalian nuclear localization signals, the transformed bovine macrophage cell line BoMac (36) was transfected with the pls11-SuAT1 construct. A single cell line stably transfected with SuAT1 was obtained but took longer to become established relative to cell lines transfected with the expression vector control (pls11). When cell growth was analyzed (Fig. 5A), SuAT1-transfected cultures incubated in the presence of hygromycin showed a significant reduction (1.8-fold) in the number of cells relative to those of the control cultures. One explanation for these results was that the SuAT1-transfected cells expressed a lower level of resistance to hygromycin than the control cells. This possibility was supported by the increased level of growth relative to that of the control cells following the removal of hygromycin (Fig. 5A). Therefore, to control for a possible detrimental effect of hygromycin on the SuAT1-transfected cells, all subsequent analyses included SuAT1-BoMac cells that were cultured in the absence of hygromycin for 4 weeks or more.

An examination of cell morphology showed that the expression of SuAT1 had a marked effect on BoMac cells. Relative to the pls11-BoMac constructs, the SuAT1-BoMac cells appeared to be more spread out and significantly larger and possessed larger nuclei (Fig. 5B). These general changes in morphology were specific to the SuAT1-transfected cells and were detected both in the absence and in the presence of hygromycin. To test if these morphology changes were associated with the expression of the SuAT1 polypeptide, immunofluorescence and immunoblotting were performed with the anti-SuAT1 serum. The results showed that a 100-kDa polypeptide was specifically localized to the nuclei of the SuAT1-transfected cells cultured in the absence or presence of hygromycin (Fig. 5C and D).

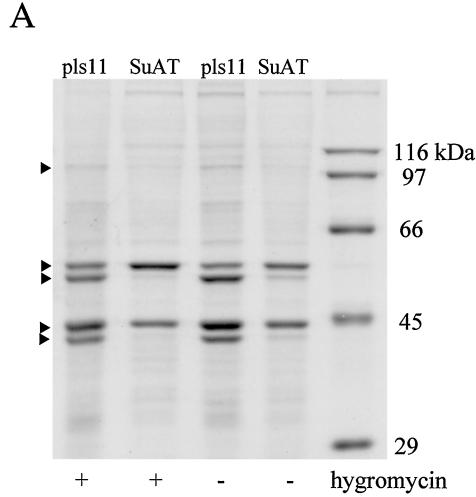

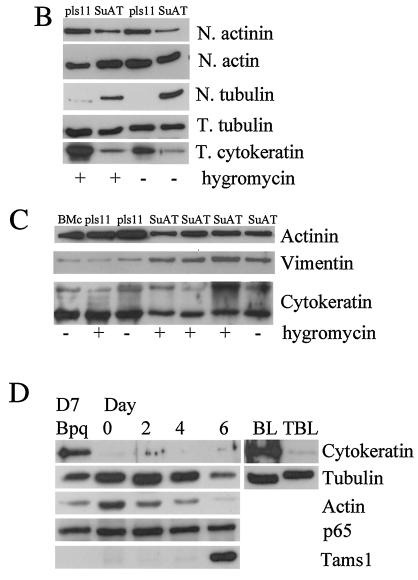

SuAT1 and T. annulata modulate the expression pattern of cytoskeletal proteins.

To investigate whether the SuAT1-associated alteration of BoMac morphology was linked to changes in the profile of cellular polypeptides, protein extracts of SuAT1- and pls11-transfected BoMac cells were separated by SDS-PAGE. Initial analysis was performed with total extracts, and alterations were observed in major polypeptides of 53 and 41 kDa (data not shown). Subsequent analysis of isolated nuclei extracted with SDS sample buffer confirmed and clarified these alterations and identified modulations of other polypeptides. These alterations are shown in Fig. 6A and were manifest in SuAT1-BoMac cells grown in both the presence and the absence of hygromycin as a reduction in a band at approximately 100 kDa, an increase in a band at 55 kDa, a major reduction in bands at 53 and 41 kDa, and a possible reduction in a band at 43 kDa. As the major alterations at 53 and 41 kDa were not detected in nuclear fractions extracted by 300 mM NaCl (data not shown), it was postulated that the expression of SuAT1 modulates the profile of major polypeptides that may be components of cytoskeletal intermediate filaments (1). This postulation was tested by excising gel slices containing the representative bands, fragmenting the proteins with trypsin, and sequencing the resulting peptides by nanospray tandem mass spectrometry. The resulting peptide sequences were then used to search the NCBI database for identity. The most significant matches for each band (Table 1) were as follows: band 1, actinin; band 2, vimentin; band 3, cytokeratin 8; band 4, actin; and band 5, cytokeratin 19. These results provide evidence that SuAT1 modulates the expression profile of cytoskeletal polypeptides in BoMac cells. Confirmation of these alterations was obtained by using commercial antisera specific for cytoskeletal polypeptides to probe immunoblots of total cellular and nuclear fraction protein extracts. As shown in Fig. 6B and C, the immunoblots provided further evidence that alterations to the nuclear profile of actinin, vimentin, and cytokeratin were associated with SuAT1-transfected BoMac cells, while no significant differences were observed with the antiactin antibody. In addition, it appeared that levels of tubulin associated with the nuclear fractions were increased in SuAT1-BoMac cells relative to that of actin. However, the only alteration detected with the total protein extracts was the marked reduction of cytokeratin levels (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses of SuAT1-transfected and Theileria-infected cell lines. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of nuclear extracts derived from BoMac cells transfected with pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 (SuAT) constructs cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of hyrgomycin; (B) total (T) and nuclear (N) extracts of BoMac cells transfected with pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 (SuAT) constructs cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of hyrgomycin; (C) normal BoMac nuclear extract (BMc) and multiple nuclear extracts of BoMac cells transfected with pls11 or pls11-SuAT1 (SuAT) constructs cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of hyrgomycin; (D) total extracts of infected D7 cells treated with buparvaquone for 72 h (Bpq); extracts from untreated D7 cells cultured at 37°C (day 0) and 41°C for 2, 4, and 6 days; and extracts of uninfected (BL) and infected (TBL) BL20 cells. Immunoblots were probed with antibody against the designated polypeptides actinin, actin, tubulin, pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, NF-κB-p65, and Tams1.

TABLE 1.

Tryptic peptides of BoMac cytoskeletal proteins sequenced by mass spectrometry

| Band | Most significant match | NCBI accession no. | Scorea | Peptides matched |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alpha actinin | NP_068695 | 1,478 | ETTDTDTADQVIASFK plus 25 others |

| 2 | Vimentin | NP_776349 | 647 | DGQVINETSQHHDDLE plus 19 others |

| 3 | Cytokeratin 8 | P05786 | 505 | LEGLTDEINFYR plus 14 others |

| 4 | Actin | ATBOG | 792 | LCYVALDFEQEMATAASSSSLEK plus 16 others |

| 5 | Cytokeratin 19 | P08728 | 700 | QSSSTSSFGGMGGGMR plus 20 others |

The score is −10 times the log of P, where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event. Individual ions scores greater than 49 indicate identity or extensive homology (P < 0.05).

The results described above show that a Theileria gene localized to the host nucleus is associated with an alteration of the BoMac cell phenotype and the expression profile of structural polypeptides. To test whether changes to the cytoskeleton are associated with Theileria infection, we repeatedly attempted to infect the BoMac cells with T. annulata sporozoites but did not succeed, and we have been unable to transfect the uninfected BL20 cell line with SuAT1 (data not shown). The reason for this finding is unclear, but as an invasion of sporozoites appeared to have taken place, it may be that prior transformation of the macrophage is refractory to macroschizont establishment. Therefore, we analyzed the profile of cytoskeletal polypeptides in total extracts of the infected D7 cell line after treatment with the theileriacidal drug buparvaquone and during a time course of differentiation into merozoites (Fig. 6D). No reactivity was obtained with the antivimentin antibody, and no alteration to the level of actinin was detected (data not shown). Interestingly, the level of a 53-kDa polypeptide detected by the anticytokeratin antibody showed a significant increase in extracts from buparvaquone-treated cells compared to that in untreated extracts. This increase was not detected with either the tubulin or the actin antibodies. We also tested the levels of cytokeratin in extracts of uninfected and Theileria-infected BL20 cells. The results indicate that infection by Theileria is associated with a reduction in cytokeratin levels. Analysis of the differentiation time course did not show major differences in the level of cytokeratin relative to that of macroschizont-infected cells at day 0. In contrast, the levels of actin showed a significant reduction relative to those of tubulin and NF-κB as early as day 2, and this reduction continued through to day 4, while both actin and tubulin polypeptides appeared to show reduced levels at day 6 relative to that of p65 (Fig. 6D). There was no reactivity with the antiactin antibody against a parasite-enriched piroplasm extract (data not shown). An elevation in the level of the major merozoite antigen, Tams1, demonstrated that the parasite had undergone differentiation to the merozoite.

DISCUSSION

Altering the host cell environment is likely to be essential for the establishment, survival, and reproduction of intracellular parasites, in general (42). For some parasites, this process will involve the subjugation of the molecular pathways that control fundamental cellular processes such as differentiation, apoptosis, and division. Theileria parasites provide a good model to study these events because the parasite dedifferentiates the host cell, alters the profile of gene expression, and modulates the pathways that regulate leukocyte proliferation and apoptosis. Control over the leukocyte has largely been attributed to the macroschizont stage of the parasite. From the data generated in this study, however, it is feasible that parasite-mediated control of the host cell is actively maintained as the macroschizont undergoes stage differentiation to the merozoite.

SuAT1 was isolated by the ability of the encoded polypeptide to bind DNA, and two DNA binding motifs were identified in the predicted amino acid sequence, one of which showed high identity to AT hook motifs that have been found in a wide range of eukaryotic DNA binding proteins (3), including the TashAT factors of T. annulata (37, 38). This finding may explain the binding of SuAT1 to the CAT1 concatenated probe, as CAT1 has an AT-rich motif that also binds to an AT hook bearing a fragment of TashAT1 (38). Although SuAT1, like the TashAT polypeptides, is expressed in the macroschizont-infected cell, it is unlikely, for several reasons, to perform an identical functional role. First, while the conserved AT hook motif suggests that SuAT1 can bind to the narrow minor groove of AT-rich DNA and influence transcriptional regulation of its target genes, the divergence from the first and third AT hooks of TashAT2 and TashAT1-3 and the possession of the second predicted DNA binding domain indicates that SuAT1 may recognize a different subset of target genes. Second, the RNA and polypeptide expression profiles of SuAT1 are distinct from those of the TashATs; during the differentiation process, TashAT2 and TashAT3 are down-regulated at the same time (between days 2 and 4) that host cell division begins to subside, whereas the level of SuAT1 in the leukocyte nucleus was detected at elevated levels at the day 4 time point, and SuAT1 expression was clearly maintained in cells with parasites undergoing merozoite production. It appears, therefore, that there is a requirement for SuAT1 in the host nuclei of infected cells at time points associated with the inhibition of host cell division. Thus, it is unlikely that SuAT1 is involved in the stimulation of host cell proliferation, although it is possible that its function is altered during differentiation by a changeover of partner binding proteins or a reduction in the level of macroschizont-specific regulatory proteins.

Transfection of the transformed BoMac cell line was carried out, which confirmed that the SuAT1 polypeptide has structural information for localization to the host cell nucleus. Under constant hygromycin selection pressure, the level of growth of the SuAT1-transfected cells was significantly reduced. While this result was most likely due to a reduced level of resistance of these cells to hygromycin, it is also possible that SuAT1 itself may alter cell viability. Indeed, we have found that the expression of SuAT1 in transfected COS7 cells in the absence of drug limits culture growth (Shiels and McKellar, unpublished data), and as SuAT1 possesses both cyclin docking and CDK phosphorylation motifs, it might interact with regulatory complexes of the cell division cycle. Experiments with an inducible expression system being used to test the influence of SuAT1 on cell division and/or apoptosis are in progress.

As shown in Fig. 5, the expression of SuAT1 was associated with altered morphology of the BoMac cells. Transfected cells were also shown to have an altered expression profile of cytoskeletal polypeptides, and based on their role in determining cell structure (1), it is possible that these events are linked. How these changes are brought about requires clarification, but as the changes to actinin, tubulin, and vimentin were not detected in total extracts, they are unlikely to result from direct changes to the control of expression of cytoskeletal genes and may be due to a reorganization of the cytoskeleton. In contrast, levels of cytokeratin polypeptides appear to be repressed following transfection with SuAT1, and analyses of extracts derived from buparvaquone-treated macroschizont-infected cells indicated that parasite infection results in lower levels of a 53-kDa cytokeratin polypeptide (Fig. 6D). The low level of expression was maintained during parasite differentiation, and we also detected a lower level of the 53-kDa polypeptide in macroschizont-infected cells compared to uninfected BL20 lymphoblastoid cells. Thus, it appears that both SuAT1 and the parasite are associated with the repression of cytokeratin gene expression. This is a surprising result, as cytokeratins are thought to be intermediate filaments of epithelial cells and are not normally associated with cells of lymphoid or myeloid lineage (1). However, as the aberrant expression of cytokeratin genes has been detected in transformed cells of nonepithelial origin (20), it can be postulated that this also occurs following transformation by T. annulata. This may in turn be detrimental to parasite establishment and may require repression by the macroschizont in the infected cell. Recent work has shown that the expression of cytokeratin polypeptides can both induce and inhibit cellular proliferation (27).

Mammalian AT hook polypeptides control gene expression (41), and it has been demonstrated that they are involved in the determination of cell fate by the modulation of differentiation and division of myeloid cells (4, 7). Theileria AT hook polypeptides may perform similar functions in infected cells, but this has yet to be determined. Nevertheless, SuAT1 does have the potential to alter the phenotype of mammalian cells, and it is conceivable that this function provides a selective advantage for the parasite. For example, Theileria infection of leukocytes alters the morphology of these cells, and it is known that the macroschizont interacts with components of the host cell cytoskeleton (31). Differentiation to the merozoite is also associated with significant changes to the leukocyte phenotype; during parasite differentiation, the leukocyte stops dividing, enlarges, becomes filled with the differentiating parasite, and is eventually destroyed (32). These events may require active control via parasite molecules transported to the host cell compartment. It may also be relevant that the level of cellular actin appears to be reduced during merogony, as this might relax the structural integrity of the host cell and may be involved in the cessation of leukocyte proliferation (17). Direct investigation of the role that SuAT1 and related polypeptides play in modulating the phenotype of infected cells is required to fully understand their function.

This study has highlighted the possibility that parasite polypeptides with functional motifs related to those of higher eukaryotic factors will generate phenotypic alterations when expressed in, or transported to, nucleated mammalian cells. This property is unlikely to be limited to Theileria polypeptides, and it is known that the trans-sialidase of Theileria cruzi can modulate host cell apoptosis (9). Putative polypeptides that bear AT hook motifs are present in the genomes of Toxoplasma gondii (accession number tg_9397; http://ToxoDB.org/cgi-bin/toxodb/) and Plasmodium falciparum (accession number PFC0325c; http://PlasmoDB.org) (13). This finding suggests that AT hook proteins are conserved among members of the phylum Apicomplexa and are likely to be involved in the modulation of parasite (and, in some cases, possibly host cell) gene expression. Given that parasite polypeptides have evolved to specifically subjugate mammalian regulatory pathways, it is conceivable that they will provide insight into novel and efficient mechanisms that control the phenotypes of mammalian cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (058933) and the European Union INCO-DEV program (ICA4-2000-30020).

We thank Andy Tait and Collette Britton for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Vicky Gillan for Microsoft Excel expertise.

Genomic data were provided by The Institute for Genomic Research (supported by NIH grant number AI05093) and by the Sanger Center (Wellcome Trust). Expressed sequence tag sequences were generated by Washington University (NIH grant number 1R01AI045806-01A1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberts B., D. Bray, J. Lewis, M. Raff, K. Roberts, and J. D. Watson. 1989. The cytoskeleton, p. 613-680. In M. Robertson (ed.), Molecular biology of the cell, 2nd ed. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aravind, L., and D. Landsman. 1998. AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:4413-4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayton, P. M., and M. L. Cleary. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis mediated by MLL fusion proteins. Oncogene 20:5695-5707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramanian, B., C. V. Lowry, and R. S. Zitomer. 1993. The Rox1 repressor of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae hypoxic genes is a specific DNA-binding protein with a high-mobility-group motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:6071-6078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, C. G. D., A. G. Hunter, and A. G. Luckins. 1990. Diseases caused by protozoa, p. 161-226. In M. M. H. Sewell and D. W. Brocklesby (ed.), Handbook on animal diseases in the tropics, 4th ed. Baillière Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 7.Caslini, C., A. Shilatifard, L. Yang, and J. L. Hess. 2000. The amino terminus of the mixed lineage leukemia protein (MLL) promotes cell cycle arrest and monocytic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2797-2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaussepied, M., D. Lallemand, M. Moreau, R. Adamson, R. Hall, and G. Langsley. 1998. Upregulation of Jun and Fos family members and permanent JNK activity lead to constitutive AP-1 activation in Theileria-transformed leukocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 94:215-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuenkova, M. V., and M. A. Pereira. 2000. A trypanosomal protein synergizes with the cytokines ciliary neurotrophic factor and leukemia inhibitory factor to prevent apoptosis of neuronal cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:1487-1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cokol, M., R. Nair, and B. Rost. 2000. Finding nuclear localisation signals. EMBO Rep. 1:411-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux, J., P. Haeberli, and O. Smithies. 1984. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:387-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobbelaere, D., and V. Huessler. 1999. Transformation of leukocytes by Theileria parva and T. annulata. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 53:1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner, M. J., N. Hall, E. Fung, O. White, M. Berriman, R. W. Hyman, J. M. Carlton, A. Pain, K. E. Nelson, S. Bowman, I. T. Paulsen, K. James, J. A. Eisen, K. Rutherford, S. L. Salzberg, A. Craig, S. Kyes, M. S. Chan, V. Nene, S. J. Shallom, B. Suh, J. Peterson, S. Angiuoli, M. Pertea, J. Allen, J. Selengut, D. Haft, M. W. Mather, A. B. Vaidya, D. M. Martin, A. H. Fairlamb, M. J. Fraunholz, D. S. Roos, S. A. Ralph, G. I. McFadden, L. M. Cummings, G. M. Subramanian, C. Mungall, J. C. Venter, D. J. Carucci, S. L. Hoffman, C. Newbold, R. W. Davis, C. M. Fraser, and B. Barrell. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 419:498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass, E. J., E. A. Innes, R. L. Spooner, and C. G. Brown. 1989. Infection of bovine monocyte macrophage populations with Theileria annulata and Theileria parva. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 22:355-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gubbels, M. J., F. Katzer, G. Hide, F. Jongejan, and B. R. Shiels. 2000. Generation of a mosaic pattern of diversity in the major merozoite-piroplasm surface antigen of Theileria annulata. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 110:23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall, C., D. M. Nelson., X. Ye, K. Baker, J. A. DeCaprio, S. Seeholzer, M. Lipinski, and P. D. Adams. 2001. HIRA, the human homologue of yeast Hir1p and Hir2p, is a novel cyclin-cdk2 substrate whose expression blocks S-phase progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1854-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, S., and D. E. Ingber. 2000. Shape dependent control of cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis: switching between attractors in cell regulatory networks. Exp. Cell Res. 261:91-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hulliger, L. 1965. Cultivation of three species of Theileria in lymphoid cells in vitro. J. Protozool. 12:649-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinter, M., and N. E. Sherman. 2000. Protein sequencing and identification using tandem mass spectrometry. Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 20.Knapp, A. C., and W. W. Franke. 1989. Spontaneous losses of control of cytokeratin gene expression in transformed, non-epithelial human cells occurring at different levels of regulation. Cell 59:67-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luder, C. G. K., U. Gross, and M. F. Lopes. 2001. Intracellular protozoan parasites and apoptosis: diverse strategies to modulate parasite-host interactions. Trends Parasitol. 17:480-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McHardy, N., L. S. Wekesa, A. T. Hudson, and A. W. Randall. 1985. Antitheilerial activity of BW720C (buparvaquone): a comparison with parvaquone. Res. Vet. Sci. 39:29-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melhorn, H., and E. Schein. 1984. The piroplasms: life cycle and sexual changes. Adv. Parasitol. 23:37-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno, S., and P. Nurse. 1990. Substrates for p34cdc2: in vivo veritas? Cell 61:549-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. Von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ole-MoiYoi, O. K., W. C. Brown, K. P. Lams, A. Nayer, T. Tsukamoto, and M. D. Macklin. 1993. Evidence for the induction of casein kinase II in bovine lymphocytes by the intracellular protozoan parasite Theileria parva. EMBO J. 12:1621-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paramio, J. M., M. L. Casanova, C. Segrelles, S. Mittnacht, E. B. Lane, and J. L. Jorcano. 1999. Modulation of cell proliferation by cytokeratins K10 and K16. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:3086-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rechsteiner, M., and S. W. Rogers. 1996. PEST sequences and regulation by proteolysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:267-271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sager, H., W. C. Davis, D. A. Dobbelaere, and T. W. Jungi. 1997. Macrophage-parasite relationship in theileriosis. Reversible phenotypic and functional dedifferentiation of macrophages infected with Theileria annulata. J. Leukoc. Biol. 6:459-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sager, H., C. Brunschwiler, and T. W. Junge 1998. Interferon production by Theileria annulata-transformed cell lines is restricted to the beta family. Parasite Immunol. 20:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw, M. K. 1997. The same but different: the biology of Theileria sporozoite entry into bovine cells. Int. J. Parasitol. 27:457-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiels, B. R., J. Kinnaird, S. McKellar, T. Dickson, L. Ben-Miled, R. Melrose, D. Brown, and A. Tait. 1992. Disruption of synchrony between parasite growth and host cell division is a determinant of differentiation to the merozoite in Theileria annulata. J. Cell Sci. 101:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiels, B. R., M. Fox, S. McKellar, J. Kinnaird, and D Swan. 2000. An upstream element of the TamS1 gene is a site of DNA-protein interactions during differentiation to the merozoite in Theileria annulata. J. Cell Sci. 113:2243-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiels, B. R., A. Smyth, J. Dickson, S. McKellar, L. Tetley, K. Fujisaki, B. Hutchinson, and J. H. Kinaird. 1994. A stoichiometric model of stage differentiation in the protozoan parasite Theileria annulata. Mol. Cell. Differ. 2:101-125. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiels, B. R. 1999. Should I stay or should I go now: a stochastic model of stage differentiation in Theileria annulata. Parasitol. Today 15:241-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stabel, J. R., and T. J. Stabel. 1995. Immortalization and characterization of bovine peritoneal macrophages transfected with SV40 plasmid DNA. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 45:211-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swan, D. G., K. Phillips, A. Tait, and B. R. Shiels. 1999. Evidence for localisation of a Theileria parasite AT hook DNA-binding protein to the nucleus of immortalised bovine host cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 101:117-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swan, D. G., R. Stern, S. McKellar, K. Phillips, C. Oura, T. I. Karagenc, L. Stadler, and B. R. Shiels. 2001. Characterisation of a cluster of genes encoding Theileria annulata AT hook DNA-binding proteins and evidence for localisation to the host cell nucleus. J. Cell Sci. 114:2747-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swan, D. G., L. Stadler, E. Okan, M. Hoffs, J. Katzer, S. McKellar, and B. R. Shiels. 2003. TasHN, a Theileria annulata encoded protein transported to the host nucleus displays an association with attenuation of parasite differentiation. Cell. Microbiol. 5:947-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swan, D. G., K. Phillips, S. McKellar, C. Hamilton, and B. R. Shiels. 2001. Temporal co-ordination of macroschizont and merozoite gene expression during stage differentiation of Theileria annulata. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 113:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thanos, D., and T. Maniatis. 1992. The high mobility group protein HMGI(Y) is required for NFκB-dependent virus induction of the human IFN-β gene. Cell 71:777-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trager, W. 1986. Living together: the biology of animal parasitism. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.