Abstract

In neurodegenerative disorders effective treatments are urgently needed, along with methods to detect that the treatment worked. In this review we discuss the rapid progress in the understanding of recessive proximal spinal muscular atrophy and how this is leading to exciting potential treatments of the disease. Spinal muscular atrophy is a caused by loss of the Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1) gene and reduced levels of SMN protein. The critical downstream targets of SMN deficiency that result in motor neuron loss are not known. However, increasing SMN levels has a marked impact in mouse models, and these therapeutics are rapidly moving towards clinical trials. Promising preclinical therapies, the varying degree of impact on the mouse models, and potential measures of treatment effect are reviewed. One key issue discussed is the variable outcome of increasing SMN at different stages of disease progression.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) describes a group of lower motor neuron disorders with genotypic and phenotypic diversity that can be inherited as dominant, recessive or X-linked traits. The focus of this review will be on the most common form of SMA, 5q proximal recessive SMA caused by loss or mutation of the Survival Motor Neuron 1 gene (SMN1) and retention of the SMN2 gene1. SMA has a frequency of 1/11,000 new births2-4 and carrier frequencies that range from 1/47-1/72 depending on racial group4. SMA represents the most common genetic cause of infant death5. Many other types of SMA are related to mutated genes that are expressed in not just the nervous system but in a wide range of tissues. This is also the case with SMN expression, and the reason for selective motor neuron or motor circuit involvement in 5q SMA is not known1, 6. Proximal 5q SMA can be classified clinically into five subtypes based on severity and onset7. Type 0 is the most severe subtype and is characterized by weakness at birth. Type 1 is the most common subtype and is associated with onset prior to 6 months of age and the lack of ability to sit independently. Without ventilatory support, death usually occurs prior to age 2 in type 1 SMA. Onset of type 2 occurs between 6-18 months and the ability to sit upright is achieved while ambulation is not. Type 3 has onset after 18 month of age and ambulation is at least temporarily achieved. The mildest subtype is type 4 characterized by mild proximal weakness with adult onset8, 9.

Genetics of 5q SMA and phenotype modification in man

The loss or mutation of SMN1 and the retention of SMN2 causes SMA1, 6. SMN1 and SMN2 differ by a single nucleotide in exon7 that does not alter an amino acid but does alter a splice modulator10-12. The majority of the transcript from SMN2 lacks exon7 thus the resulting SMN protein does not oligomerize efficiently and is degraded13-16. The copy number of both SMN1 and SMN2 vary in the population, which is particularly relevant to the severity of this disease4, 17. Additional copies of the SMN2 gene can modify the SMA phenotype with an inverse correlation of phenotypic severity and copy number17, 18. Spinal muscular atrophy has been modeled in mice by placing a human SMN2 transgene on the background of a homozygous loss of function mouse Smn allele19-21. The introduction of two copies of SMN2 into a Smn knockout mouse results in a severe SMA like phenotype and death at 5 days. The presence of eight copies of SMN2 on this background results in mice that are essentially normal. The addition of a transgene expressing SMNΔ7 (SMN lacking the exon7 sequence) along with two copies of SMN2 extends lifespan of the mouse to ∼14 days. In addition to alterations in the SMN2 copy number, variants in SMN2 gene have been identified that result in increased full-length SMN production. One such variant is 859G>C in exon7 of SMN2 that increases full-length transcript by about 20% and is found in patients with mild SMA22-24. Interestingly, this variant occurs in two copies in milder type 3b patients, one copy in type 2 patients, and does not occur at all in severe type 1 patients22-24. This leads to the prediction that a 20% increase in full-length SMN mRNA in 2 copy SMN2 patients will likely result in type 3b SMA and most likely a 25% increase in full-length SMN mRNA in those same patients would result in no SMA phenotype22, 24.

In addition to variants within the SMN2 gene there are also modifiers of SMA that lie outside the SMN locus. This is clear from haploidentical siblings with the same copy number of SMN2 that have different SMA severities17, 25-27. While families with type 2 and 3 SMA siblings are most common, a similar phenomenon also occurs with type 1 and type 2 SMA siblings28, 29. Plastin 3 mRNA has been reported to be markedly elevated in some milder siblings and is suggested to be a modifier of SMA30. However, high Plastin 3 mRNA levels are also found in female siblings with the more severe SMA phenotype31. One possibility is the Plastin 3 modifier is female dependent and incompletely penetrant. An alternative theory is that Plastin 3 is not a critical modifier of SMA phenotype. The role of Plastin 3 in SMA remains uncertain as no DNA changes in the Plastin 3 gene itself, nor any activator of Plastin 3 expression that segregates with the mild sibling, have been reported. The regulators of splicing in the SMN1 and SMN2 genes that alter incorporation of exon7 have been studied extensively. Numerous sites have been found that bind either a negative or a positive regulator of splicing32. Within some of these regulators exists a series of variants in the single nucleotide polymorphism databases. These variants could alter the activity of the splicing regulator. While to date it has not been reported, at least one possibility to explain the alteration of SMN expression in haploidentical discordant siblings could be a mutation in one of the numerous regulators of SMN2 splicing.

SMN Function

SMN has a clear canonical function in the assembly of Sm proteins onto snRNAs33. Thus it is not surprising that complete loss of SMN is lethal both to an organism and to a cell, since the assembly of snRNAs is essential in splicing6, 19, 34, 35. It remains unclear whether disruption of SMN's essential splicing function, an additional axonal SMN function, an unknown function, or some combination thereof is critical for the SMA phenotype. We have previously discussed the potential mechanisms of SMA in a review6. Understanding the mechanism of SMA is of critical importance for therapeutic development of clinically applicable targets directly downstream of SMN. The investigation of downstream genes will provide valuable targets that can be altered to improve SMA disease phenotype.

Assays of the ability of SMN to perform assembly of Sm proteins onto snRNA show a very tight correlation to SMA phenotypic severity in cells and extracts from SMA mouse spinal cord36, 37. Furthermore, there is a correlation with ability to perform snRNP assembly and the ability of a transgene to correct SMA6, 38. The predicted outcome of reduced snRNP assembly is an alteration in gene splicing due to reduced snRNP levels6, 39. As the snRNPs most affected by SMN reduction are those involved in splicing minor introns, genes containing minor introns are predicted to be the primary target of reduced snRNP assembly37-39.

Splicing has been examined in tissues where SMN is reduced and, provided samples are assayed early in the SMA disease progression, there are minimal splicing changes40. Thus it appears that SMN deficiency does not produce a plethora of splicing changes40. We do not consider small (2-5%) changes likely to have any major consequence on the cell. Using laser capture microdissection Ruggi et al have shown that the amount of full-length SMN from SMN2 is lower in motor neurons in normal mice than in other neuronal cell types, providing a partial explanation of why motor neurons are selectively affected41. To date there is no comprehensive data on the splice changes that occur specifically in SMA motor neurons. It is likely that there are only a few critical downstream targets altered upon SMN deficiency as it appears that not all, or even most genes, are significantly affected by reduced SMN.

One change with SMN reduction that has been reported in both Drosophila and mouse is the splicing of the minor intron in the stasimon gene39, 42. The stasimon gene shows an approximately 30% reduction of a spliced isoform in motor neurons and 40% in proprioceptive neurons of the SMA mouse39. In Drosophila with reduced SMN the total larvae shows a similar level of splice alteration (30%). The exact level of alteration in either the Drosophila proprioceptive neurons or motor neurons is not clear39. Expression of stasimon in the SMN deficient fly does correct some of the larval NMJ defects but not all. In addition, it is not clear whether the exon deficient isoform shows any rescue ability as opposed to the full-length isoform39. While this data clearly shows that a U11/U12 intron is affected in SMA mice, the crucial nature of the target in SMA needs to be confirmed by additional experiments. For instance, does knockdown of stasimon in vivo in mouse neurons produce an SMA like phenotype or does replacement of stasimon in the SMA mouse have any effect?

In Drosophila the mutant SMN alleles are non-functional, and the larvae are reliant on maternal SMN43. SMN deficient Drosophila show decreased movement, defective motor rhythm and abnormal neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction in larva42. These phenotypes can be corrected by expression of SMN in cholinergic neurons, but not by expression of SMN in glutamatergic or GABAergic neurons42. In Drosophila the motor neuron is glutamatergic whereas the proprioceptive neuron is cholinergic. Previous studies in the SMA mouse have suggested the importance of the proprioceptive neurons in effecting the output of the motor neuron44. In addition, correction of SMN in just motor neurons or just muscle of SMA mice does not have a major impact on survival yet correction in all neurons does45-47. Interestingly, the expression of SMN in motor neurons can correct the neurotransmitter release properties at the NMJ and restore the synaptic stripping on the motor neuron46, 47. Importantly, removal of SMN from the motor neuron in the presence of two copies of SMN2 does result in a clear motor neuron phenotype although the mice do survive longer than Δ7SMA mice48. There is profound reduction in muscle bulk and changes in developmental markers of muscle in SMA49. This has led to the suggestion that high SMN levels above those from two copies of SMN2 are required in muscle tissue. While this is possible, it is difficult to separate the indirect atrophic effects of denervation from direct effects of SMN deficiency on muscle atrophy and development. High expression of SMN in just muscle does not correct the SMA phenotype in mice45. Whether complete SMA treatment will require expression of high SMN levels in multiple tissues including muscle remains to be determined.

The mouse and human have considerably more introns than lower organisms. Therefore it remains very important to obtain a complete catalogue of splice alterations in neurons. In this regard, it is essential to have RNA-seq data on motor neurons along with suppression and knockdown studies using scAAV9 delivery in SMA mice. This will allow the definition of critical downstream targets. Induced pluripotent stem cells have been developed from SMA patients and neurons/motor neurons do show a mild phenotype50 These cells are being used in screens to identify drug compounds. Again RNA-seq data from these cells would be useful along with the identification of factors that suppress phenotypes in these cells. This will afford the opportunity to compare the changes occurring in vivo in animal models of SMA with those found in vitro in human cells.

SMN has been reported to interact with a large number of proteins. Whether all these interactions really contribute to a function in the cell remains debatable6. It is important to note that biochemical studies using SMN missense mutations in vitro in culture need to be interpreted with care due to the ever present full-length wild-type SMN in the cell. In vivo in the mouse, mild SMN missense mutants interact with wild-type SMN to form functional complexes (complementation) whereas SMN missense mutants on their own are nonfunctional38.

It is important to consider functions other than snRNP assembly that could be involved in the development of SMA. SMN is found in low amounts in the axon and reduction of SMN leads to reduced β -actin mRNA transport and axon defects51-53. This has led to the suggestion that SMN has a unique function and interacts with some different proteins in the axon. The question that arises include: What is this axonal complex and can it be assayed biochemically? Certainly it is possible that the Lsm proteins54 or others could be assembled onto mRNA for transport down the axon. If this is the case this assembly reaction can be measured and correlated to reduced Sm assembly in SMA6. SMN has been reported to interact with the golgi adaptor protein Alpha Cop55, 56 as well as HuD57, 58. These proteins are present in some RNA granules in the axons yet it is difficult to reconcile the significance of these SMN complexes when relatively few particles in the axon show complete overlap. Furthermore, how are these various complexes maintained in equilibrium in the cytoplasm where different SMN partners are competing with each other for the same spot on SMN? Finally, overexpression of these binding partners should act in dominant negative manner to compete out the other SMN functions if these multiple complexes do in fact occur in the same cell. If transport of mRNA is a critically affected function in SMA then it becomes important to determine what will suppress the phenotype. Our preference is that a clear strong suppression of the SMA phenotype be obtained in the mouse. For example, overexpression of HuD has been reported to suppress axonal defects in cultured cells but this finding has not been tested in vivo by scAAV9 delivery into the SMA mouse57. If strong suppression can be shown then this is both a new target for therapeutics and evidence for the importance of that particular mechanism in SMA.

Current therapies and what has been tested in SMA

The clinical management of SMA is designed to address the secondary effects of muscle weakness, and the standards of care for SMA have been described elsewhere59. Outside of supportive care, there are currently no effective therapeutic interventions available for SMA. A number of drug compounds have been tested in SMA clinical trials, but to date none have proven clearly effective. These studies include both presumed neuroprotective agents and those expected to induce SMN. Studies with gabapentin and riluzole for neuroprotective effects showed no benefit60, 61. Several small molecule compounds, some of which are available clinically for other non-SMA related FDA-approved indications, have been shown to promote inclusion of exon7 in SMN2 transcripts by alteration of splicing and or induction of SMN expression levels. However in all cases these compounds were found by induction of SMN in patient fibroblast lines. Given this is a dividing cell and not a motor neuron the possibility exists that these compounds do not induce SMN in vivo in the required cell types. Indeed we have found this to be the case for a number of molecules when tested in mice (unpublished observation). Of the compounds reported to induce SMN in cultured cells, phenylbutyrate, hydroxyurea, and valproic acid have been taken to clinical trial without evidence of clinical benefit62-67. Salbutamol increased full-length SMN protein production in fibroblasts from SMA patients68, but clinical trials showed only a modest effect and blinded, placebo controlled studies have not been performed69. There are multiple factors that could contribute to the failure of these clinical trials. First and foremost would be the lack of clear data that the compounds induce SMN in the required cell types in vivo. Second is the inappropriate timing of treatment delivery (i.e. in late symptomatic patients). It is increasingly becoming clear that at least in SMA model mice there is a therapeutic window when increased SMN protein is needed for motor neuron survival and an improvement in phenotype70, 71. Most SMA patients enrolled in these trials have possibly been outside this therapeutic window where increasing SMN levels would be predicted to have an effect. One key aspect that is not fully understood is the requirement for increased SMN in the different types of SMA, and whether increasing SMN later in the course of disease in type 2 and 3 patients will allow the remaining motor neurons to function better or not. The timing of motor neurons loss in SMA type 2 and 3 and whether there is a specific window of development which overlaps type 1 is not known. To get complete answers to these questions will require human clinical trials with the strong SMN restoring agents that have recently been developed. While we cannot be certain that early induction of SMN is required for correction of SMA in humans, understanding the biology of SMA and the consideration of this possibility is important in clinical trial design and interpretation. Although there have been problems with the initial drug compounds evaluated, there are now SMN inducers in the pipeline that clearly have a major impact on the SMA mouse models in vivo.

Therapeutic Pipeline for SMA in 2013

Currently the main targets for therapeutics in SMA are increasing SMN from SMN2 or restoration of SMN levels using gene therapy. Other therapeutic possibilities such as stem cells that can differentiate into motor neurons, neuroprotective strategies and the use of targets downstream of SMN deficiency (once defined) are significantly behind the progress of SMN restoration. The effects of stem cell therapies, to date, are related to trophic support of the motor neurons rather than functional motor neuron replacement72-74. The requirement of implantation of stem cells along the full length of the spinal cord and establishment of synaptic connections remain significant challenges, and currently this is an experimental concept requiring much further development. The required targets of neuroprotective therapies remain unknown, and to date, in SMA and other neurological disorders, impressive results are lacking.

Therapies targeting SMN protein restoration levels are the best supported by preclinical work and hold the most promise for an effective treatment (table 1 and 2). When SMN is restored early in SMA mouse models, a clear rescue of SMA phenotype and increase of survival occurs71, 75, 76. Approaches to increase SMN include gene therapy for SMN replacement, antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) to modify SMN2 splicing, small molecule therapies targeting modification of SMN2 splicing, extending the stability of SMN protein, and activating the SMN2 promoter (Table 1 and Table 2). Earlier reports of gene therapy in the SMA mouse demonstrated transduction of SMN to the motor neurons in the lumbar spinal cord after delivery to multiple muscles and retrograde delivery of the rabies G pseudotyped virus to the motor neurons. However this transduction is not as efficient as subsequent studies, and the lentivirus studies produced a minimal impact on survival in the SMA mouse77.

Table 1. Preclinical Gene Therapy, ASO, and Stem Cell Strategies that Extend Survival in SMA Mouse Models.

| Strategy | Dose and Delivery | Mouse | Survival Ratio (days) (Treated/Untreated) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASO to alter SMN2 splicing | ||||

| ASO(-10–27) | 8 μg ICV on P1 | 005025 | 1.6 (25/16) | Passini et al. 2011 |

| ASO(-10−27) | 20 μg ICV on P2 2× 50 μg/g SC P1.4 20μg ICV +2× 50μg/g SC 2 × 160 μg/g SC P1+P4 |

005058 | 1.7 (17/10) 10.8 (108/10) 17.3 (173/10) 24.8 (248/10) |

Hua et al. 2011 |

| PMO(-10-29) | 81µg ICV on P1 | 005025 | 7.5 (112/15) | Porensky et al. 2012 |

| PMO25(-10-34) | 40μg/g ICV on P1 | 005058 | 8.5 (85.5/9.5) | Zhou et al. 2013 |

| PMO(−10−34) | 6 mM ICV on P1 | 005025 | 8.4 (126/15) | Mitrpant et al. 2013 |

| Gene therapy to restore SMN | ||||

| scAAV9-SMN | 5 × 1011 vg IV on P1 | 005025 | 16 (>250/15.5) | Foust et al. 2010 |

| 1 × 1011 vg IV on P1 | 005025 | 5 (69.1/13.9) | Valori et al. 2010 | |

| 4.5 × 1010 vg IV on P1 | 005025 | 14.5 (199/13.7) | Dominguez et al. 2011 | |

| 2 × 1010 vg IV on P2 2 × 1010 vg ICV on P2+3 |

005025 | 2.5 (~33/~13) 9.6(~125/~13) |

Glascock et al. 2012 | |

| 2 × 1011 vg on P2 | 005024 | 2.4 (17/7) | Glascock et al. 2012 | |

| 7 × 1010 vg IM on P1 (with IV spread) | 005025 | 13.6 (163/12) | Benkhelifa-Ziyyat et al. 2013 | |

| scAAV8-SMN | 1.7 × 1010 vg ICV + Lumbar cord P1 | 005025 | 10.5 (157/15) | Passini et al. 2010 |

| SMN Trans-Splicing Vector | 1.14 × 1012 plasmid copies ICV on P1 | 005024 | Alone 1.8 (7/4) | Coady et al 2010 |

| SMN Trans-splicing/IGF-1 Dual Vector | 10 μg plasmid DNA ICV on P2 | 005024 | 1.5 (6/4) Trans-Splicing 1.8 (7/4) IGF-1 alone 2 (8/4) Combined |

Shababi et al. 2011 |

| Stem Cell | ||||

| Neural Stem Cells (NSCs) | ICV on P1 | 005025 | 1.4 (18.2/13) | Corti et al. 2008 |

| Embryonic stem cell-derived NSCs | ICV on P1 | 005025 | 1.6 (21.0/12.8) | Corti et al. 2010 |

| Genetically corrected-Induced pluripotent stem Cell-derived MNs | MNs on P1 into cervical and lumbar spinal cord | 005025 | 1.4 (19/14) SMA skinfibroblasts 1.5(21/14) Non-SMAskin fibroblasts 1.5 (21/14) Corrected SMA skin fibroblasts |

Corti et al. 2012 |

Mouse models (Jackson Lab Catalog number if available): 005024 (SMN2;Smn-/-); 005025 (SMN2;Smn-/-); 005058 ((SMN2)2Hung Smn1tm1Hung/J). The 5024 and 5025 mouse lines contain targeted deletion in the mouse Smn gene and are null for mouse SMN. Both lines also contain the human SMN2 transgene derived from line 89 which contains a single copy of SMN2 thus when homozygous as in these lines the mice contain two copies of SMN2. The 5025 line also contains two copies of a second transgene, SMNΔ7. The SMN2 in these two lines is expressed in all tissues tested to date. The line 5058 was developed by Hsieh-Le et al and contains a mouse Smn allele that disrupts exon7, and therefore has the potential to produce a truncated mouse Smn lacking exon7. The 5058 line also has the human SMN2 transgene from line 2 and has two copies human SMN2 transgene per chromosome, thus, four copies in the homozygous state. In the homozygous state line 5058 has a normal life span but shows necrosis of limbs. In general 5058 is used with the SMN2 gene in a heterozygote state so that there is 2 copies of SMN2 and the deletion in a homozygous state for a SMA mouse. The mouse line Smn 2B/- has disruption of the mouse Smn gene. The advantage of this line is that it does not show necrosis indicating that the necrosis apparent in the aforementioned models likely result from of the uneven expression of SMN due to the human promoter in a mouse background. This line also seems very sensitive to treatments when compared to 5025. The disadvantage of Smn 2B/- is that it does not contain the human SMN2 gene which is a desired therapeutic target in humans. The predictive power of these mouse lines is not currently known as there have been no successful treatments in humans. ASO: antisense oligonucleotide; PMO: phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotides; vg: viral genomes; ICV: intracerebroventricular; P: postnatal day with first day of life starting at P1; MN: motor neurons *Days

Table 2. Preclinical small molecule drugs that can successfully extend survival in mouse models of SMA.

| Strategy | Delivery/Timing | Mouse | Survival (days) (treated/untreated) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DcpS Inhibitor | ||||

| RG3039 | IP on P4 | Smn 2B/- | 6 (112/18) | Gogliotti et al. 2013 |

| 005058 | 1.4 (10/13.8) | |||

| RG3039 | IP on P1 | 005025 | 1.3 (23/18) | Van Meerbeke et al 2013 |

| ChATCreSmnRes | 1.7 (41.5/25) | |||

| 2,4-diaminoquinazoline | Oral on P4 | 005025 | 1.3 (17/14) | Butchbach et al. 2010 |

| Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor | ||||

| Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid | Oral on E15 | 005024 | Rescue of embryonic lethality | Riessland et al. 2010 |

| Oral on P1 | 005058 | 1.3 (12.9/9.9) | ||

| Trichostatin A | IP on P5 | 005025 | 1.2 (19/16) | Avila et al. 2007 |

| Trichostatin A + Nutrition | IP on P1 + nutrition P8 | 005025 | 1.7 (38/14) | Narver et al. 2008 |

| P38 and HuR Protein Activator | ||||

| Celecoxib | IP on P1-P6 | 005025 | 1.4 (18/13) | Farooq et al. 2013 |

| Proteasome Inhibitor | ||||

| Bortezomib | IP on P5 | 005025 | No effect alone 1.4 (20/14) with TSA | Kwon et al. 2011 |

| Read-through Inducing Compound | ||||

| TC007 | ICV P3,5,7 | 005025 | 1.3(16/12.6) | Mattis et al. 2009 |

| Rho-kinase Inhibitor | ||||

| (Y-27632) | Oral on P3 | Smn 2B/- | ∼14-33 wks/∼4 wks | Bowerman et al. 2010 |

| E14 +P3 | 005024 | No effect | ||

| Fasudil | Oral P3 | Smn 2B/- | 9.8 (300/30.5) | Bowerman et al. 2012 |

| STAT5 Activator | ||||

| Prolactin | IP on P1 | 005025 | 1.6 (21/14) | Farooq et al. 2011 |

| Mechanism Undefined | ||||

| PTC compounds | IP on P3 | 005025 | 11 (150/14) | Naryshkin et al. 2012 |

| LDN-76070 | IP on P2 | 005025 | 1.4 (17/11.5) | Cherry et al. 2013 |

Mouse models (Jackson Lab Catalog number, if available): 005024 (SMN2;Smn-/-); 005025 (SMN2;Smn-/-; SMNΔ7+/+); 005058 ((SMN2)2Hung Smn1tm1Hung/J); Smn 2B- (Bowerman et al. 2012). ChATCreSmnRes:5025 line with SMN restored in motor neurons but not other cell types See table 1 legend for mouse model genetics and characteristics. IP: intraperitoneal; P: postnatal day with first day of life starting at P1; E: gestational day; TSA: trichostatin A

In 2010/2011 dramatic and successful rescue of the SMA mice was reported by four groups using gene therapies to replace SMN with an adeno-associated virus-based vector76, 78-80. The AAV used was serotype 9 and self-complementary or scAAV9, this virus has the ability to cross the blood brain barrier and results in rapid expression. Various routes of delivery of scAAV9 SMN including intravenous, intracerebroventricular, and combined routes have been investigated79, 81, 82. The combined findings of preclinical work support that sufficient viral titer and transduction within the central nervous system will be critical in future clinical trials. The delivery of scAAV9 has been explored in larger animals including both primates and the pig. In large animals, scAAV9, when introduced into the vasculature, crosses the blood brain barrier and results in efficient transduction of motor neurons in various regions of the spinal cord83-85. Preclinical toxicology studies in both primates and mice indicate good safety of scAAV9-SMN, and in the near future an IND will be filed on scAAV9-SMN for an initial clinical trial in type 1 SMA using vascular delivery (Brian Kaspar and Jerry Mendell, personal communication). In addition to vascular delivery, intrathecal delivery has been investigated in large animals; again this results in efficient transduction of motor neurons and allows for a reduced viral dose to be used85-87. Studies are underway to fully optimize this route of delivery and to obtain the required toxicology studies to move this treatment to clinical trials. Gene therapy is well placed for the treatment of SMA with clear preclinical efficacy and a good toxicology profile. Autoimmunity against restored SMN, as seen in other gene therapy trials, is not predicted to occur in SMA due to the presence of endogenous SMN levels. scAAV9-SMN offers the potential one-time dosing without the requirement of repeated treatment. The main disadvantage currently is the production of the large amount of virus required for treatment.

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are powerful tools for therapeutic and investigative applications. Utilizing complementary base pair recognition to bind mRNA, ASOs can be used for gene suppression (blocking translation of RNA to protein) or modification of RNA processing and therefore exon content. ASO therapy for SMA can be designed to modify SMN2 by correcting pre-mRNA splicing (increased incorporation of SMN exon7), either by promotion of binding of splicing factors (bifunctional ASO's) or blocking hnRNPA1 binding at splice suppressor sites. We have recently extensively reviewed the use of ASOs in SMA in particular in preclinical studies88. Here we will briefly indicate the most salient features. Bifunctional ASO's are thus named due to the presence of both a domain complementary to a specific RNA and a secondary domain to facilitate splicing factors such as SR proteins. These ASOs have been used predominantly in cells in culture to induce incorporation of SMN2 exon7 in vitro and not tested in mice extensively in vivo. Morpholino and 2′-O-methoxyethyl (MOE) chemistries in particular have been used to block the negative regulators of the ISS-N1 sequence. Both chemistries result in remarkable rescue of the SMA mouse. The morpholino gives a rescue of over 100 days in SMA model mice with cerebrospinal fluid delivery89-91. In contrast MOE gives reduced efficacy with a single cerebrospinal fluid delivery but an enhanced efficacy when delivered at multiple time points and at high doses peripherally with a survival benefit of well over 100 days92. There appears a clear difference here; however it has to be remembered that the blood brain barrier in mice is relatively open at the stage of development when this ASO is delivered. Therefore it is difficult to predict exact distribution with peripheral delivery. It is our view, for numerous reasons, that motor neurons and neurons are the critical target, but which is the best chemistry to use in clinical trials for the treatment of SMA will require testing of both chemistries with rigorous preclinical data in both mice and primates. In essence the ability of ASOs to increase full-length SMN protein has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo, and preclinical studies successfully rescue mouse models of SMA when delivered early90-96. Recently two early phase trials have been initiated by ISIS Pharmaceuticals to investigate the safety and pharmacokinetics of intrathecal delivery of MOE ASO in patients with infantile-onset SMA and in older children with milder disease. The results of these studies are eagerly anticipated. Initial results indicate that for the MOE chemistry that they are safe97. The ASOs have clearly shown efficacy in animal models now the question remains how this translates into human studies. What ASO chemistry works the best with intrathecal delivery, when it needs to be given, as well as the repeat dosing requirement will all become important questions. The advantage of an ASO is the relative simple manufacture, the lack of toxicity, the clear efficacy and the specificity to target which should give minimal toxicity. The disadvantage is the lack of clear knowledge on the optimal chemistry and the difficulty of repeat dosing in a simple manner.

Table 2 lists small molecule drugs that have been developed, the associated proposed mechanism of effect, and the impact on survival in mouse models of SMA. Several histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors have been investigated in SMA mouse models in vivo with variable effects on survival, but a major problem is that currently all pan HDAC inhibitors have shown Ames positive tests and indicate a major issue for a pediatric indication such as SMA. However a number of other small molecule drugs that increase SMN production from SMN or alter splicing of SMN2 to increase incorporation of exon7 have been identified with high throughput screening. Quinazolines are shown to increase SMN2 promoter activity, and derivatives have been shown to increase SMA mouse survival to a greater or lesser degree depending on the severity of the model used.98-100 The drug is currently moving to phase one clinical trials. However drug compounds of a second generation have now been reported these compounds have been developed by PTC and Roche using HTS screens. They identified molecules that alter the splicing of SMN2 such that more exon7 is incorporated and more full length SMN is produced. These molecules have a remarkable impact on the SMA model mice increasing live span to at least 150 days when drug is removed. Thus clearly small molecules conventional drugs to alter SMN2 splicing and hence amount of SMN produced by a gene can be developed, and this offers exciting prospects for the development of conventional drugs for treatment of SMA. Potential advantages of a drug compound include straight forward manufacture, easy delivery with a reasonable expectation that the compound will be distributed to where it is required. Possible disadvantages include the potential for toxicity of the compound, in particular, with requirement of sustained use.

Future Parallel Measurements of Treatment Response in Humans and Mouse

Candidate outcome measures include muscle strength testing, motor function testing, muscle mass imaging, functional scales, quality of life questionnaires, survival, time to ventilator dependence, electrophysiology, and others101. Clinical functional scales, vital for measuring treatment effect in clinical trials, are variably hampered by the wide range of disease severity, and variably onset and progression, and age dependent factors, an issue highlighted by a report of a Rasch analysis of SMA motor scales102. Until there is an effective treatment for SMA, it remains uncertain which outcomes will be sensitive to treatment effect. Therefore, sensitive and reliable biomarkers with predictive, prognostic, and pharmacodynamics functionality are needed for effective translation of promising therapeutics, and it is ideal if markers can be similarly applied in animal models and humans to obtain parallel measurements. Proof of concept and correlation of treatment effect in target tissues using animal models can provide powerful validation of a particular biomarker's potential. Ideally measures should be tested in preclinical models using randomized, double blind, placebo intervention study design to predict findings in early clinical trials. Without accurate biomarkers and surrogate endpoints the risk is that effective treatments will be deemed ineffective due to incorrect timing or delivery or incorrect patient selection. Molecular, electrophysiological and imaging tools have been investigated as potential biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. Currently there are biomarker panels for SMA that correlate with severity of weakness and function103, 104, but whether these markers are related to the biology of the disease and will have predictive or surrogate endpoint ability remain to be determined. SMN transcripts and protein levels can be reliably measured in the peripheral blood, but these levels do not correlate with function105. Imaging modalities including ultrasound, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, and magnetic resonance have been investigated but currently have technical limitations that limit utility of the techniques. Due to the inaccessibility of the motor system and target tissues to endpoint analysis in humans, electrophysiological markers are particularly promising tools of motor unit assessment in vivo.

Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) is an electrophysiological measure of the total output of the motor units supplying a particular muscle. Failure of any portion of the motor unit (the motor neuron, axon, synapses, or innervated muscle fibers) may result in reduced CMAP size. CMAP is a simple technique, a distinct advantage, but the indirect nature of CMAP response does not take into account the process of collateral reinnervation. Therefore, the CMAP response may be partially or fully recovered with less severe motor neuron loss. Recording repetitive CMAP responses with trains of nerve stimulation can quantify failure at the synapse as suggested to occur in animal models and patients106-108. Motor unit number estimation (MUNE) is a modification of CMAP that allows an estimation of the functional motor units supplying the muscle being tested. The technique of MUNE compensates for the process of reinnervation and gives a more direct estimation of the number of motor units and the average size of individual motor unit potentials within the CMAP response. Despite this more direct assessment, the technique of MUNE requires more evaluator skill can be prone to bias, and these factors can potentially limit MUNE's applicability to multicenter clinical trials.

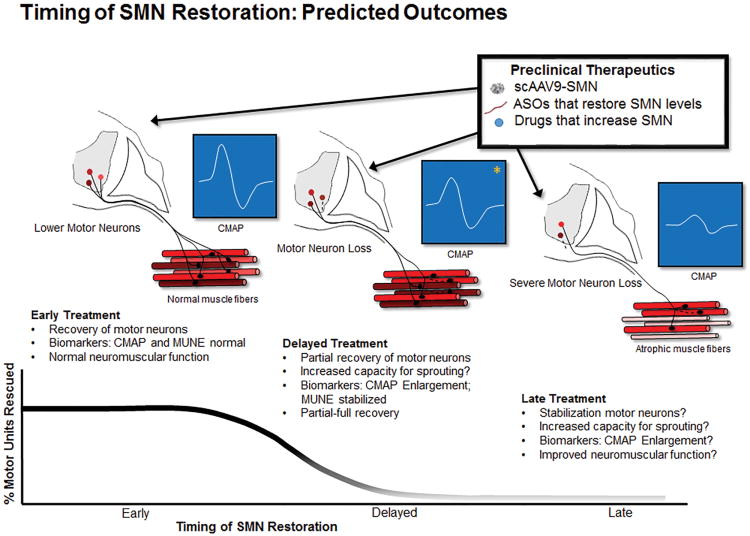

Clinically, CMAP and MUNE correlate with disease severity, functional status, SMN2 copy number, and age109-111. CMAP and MUNE have not been fully investigated in preclinical models of SMA. CMAP and MUNE can be used in mouse models to determine the precise timing of motor unit loss, and the availability of preclinical treatments with robust effect can be used to determine if CMAP and MUNE are valid surrogate endpoints of motor unit rescue. It is expected CMAP and MUNE will have predictive biomarker ability (i.e. if CMAP and MUNE are severely reduced; a robust response with SMN restoration would be less likely) and surrogate endpoint potential (measurement of a treatment effect). In SMNΔ7 mice CMAP and MUNE are reduced at onset of SMA phenotype and fully restored with early SMN restoration (unpublished observation). It is predicted that complete rescue would lead to normal CMAP and MUNE results. Whereas delayed and incomplete rescue would lead to partially preserved MUNE and the CMAP would to an extent be normalized depending on the capacity for remaining motor units for reinnervation. It remains to be determined whether SMN restoration improves the function of the motor neurons that would have otherwise survived without intervention. Thus, another possible outcome with late or delayed treatment could include no change in MUNE (no rescue of motor neurons) but increased CMAP due to enlargement of the territories of the surviving motor neurons (increased divergence or output) (figure 1). Another particularly promising technique often grouped with electrophysiology is electrical impedance myography. EIM determines impedance characteristics of muscle tissue but does not assess physiology of muscle or the motor unit and has shown significant promise as a longitudinal measure in SMA, in particular due to ease of application and non-invasive nature of the technique112.

Figure 1.

Timing of SMN Restoration and Predicted Outcomes: SMA is caused by reduced levels of SMN protein. Therapies that provide early restoration of SMN are anticipated to fully rescue motor neurons and the motor unit. When SMN restoration is delayed it is anticipated that rescue will be reduced in a time-dependent fashion. CMAP: compound muscle action potential; MUNE: motor unit number estimation. *Following delayed treatment, CMAP size may be fully corrected if there is sufficient collateral reinnervation from the remaining motor neurons.

Unmet Needs and New Directions for Research

The downstream targets of SMN remain a central and important unanswered question. The effect of SMN deficiency on splicing changes remains the most likely pathway affected but the downstream targets remain to be identified. Therefore it is critical to define all the splicing changes that occur in motor neurons when SMN is deficient, and because of non-autonomous function of motor neurons, this determination should occur with motor neuron in situ in the spinal cord. Once candidate genes are identified it is important to confirm whether identified targets can suppress the SMA phenotype. To date no such large impact genes have been found. Importantly, the expression profile of identified targets would indicate fundamental biology of the disease which can influence the development of biomarkers, understanding of the timing of the disease, and design of future therapies.

Why SMN deficiency results in motor neuron dysfunction remains uncertain. Furthermore, the specificity of the effects of SMN deficiency on motor the system has been questioned. The extra-motor phenotypic features in mouse models have prompted a closer assessment of the phenotype in human SMA. Distal extremity necrosis in mild mouse models lacking an overt phenotype of weakness and aged rescued severe mouse models have prompted the consideration of a vascular role of SMN.21, 76, 92, 96 Additionally, cardiac defects, possibly related to autonomic involvement, are described and have been corrected with SMN targeting therapies in mouse models.46, 85, 113 Other features of disordered autonomic function has been reported in aged rescued animals including priapism, bowel obstruction, and bladder distention.96 In mice, where Smn is specifically reduced and there is no dependence on the human SMN promoter, extra-motor features are lacking8. This suggests that these features may be phenomena of the human SMN promoter in the mouse rather than a true reflection of disease state. Rarely features outside the motor system have been reported, typically in patients with more severe disease, and features of autonomic involvement are incompletely defined in patients with SMA and need additional investigation. It remains an important consideration that partial restoration of SMN levels in human trials could unmask other tissues that are susceptible to low levels of SMN.

Preclinical treatments are positioned to have dramatic effects in early clinical trials provided treatments sufficiently restore SMN at the correct time and in the required target tissues. SMA natural history data, albeit limited, suggest that motor function and electrophysiological measures such as CMAP and MUNE are preserved prior to symptoms onset, even in infants with severe disease (type 1)109, 114. It is expected that treatment prior to onset of clinical and electrophysiological features of motor dysfunction will be required for optimal effects. It will be ideal to design early trials for treatment either prior to overt symptoms or as early as possible after symptom onset. The majority of clinical and electrophysiological natural history are derived from patients at later time points in the course of the disease. Additional work is required to fully define the natural history of SMA at the onset of disease, particularly in mild cases, and the determination is required regarding how long after symptom onset SMN restoration will have significant effect. Therefore we do not have a clear picture of the events that occur at the start of the disease and the timing of these events, particularly in different severities of SMA. Natural history work is ongoing using motor function measures and molecular and electrophysiological biomarkers in early symptomatic infants with SMA to further define these outcome markers in patients (ClinicalTrials.org ID: NCT01736553). This work will provide the foundation for early trials investigating SMN restoring therapies. Despite these hurdles the positive development of strong therapeutics with clear targets brings the hope that SMA can be treated or prevented if the therapeutic is provided at the correct time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all colleagues in the SMA field that have generated many discussions over the years. We also thank the patients and their families for tireless support of SMA research. We hope this cumulates with therapies that are truly effective. We in particular thank our colleagues at Ohio State University and Nationwide Children's Hospital in the motor neuron group. We thank Dr. Vicki McGovern for providing critical editorial advice in construct this article and for help with the concept of the preclinical tables. The work in the Burghes laboratory has been supported from many sources the NINDS (NS038650, NS069476), NICHD (HD06058), MDA, FSMA, Sophia's cure, Madison Fund, Preston Fund, Cade & Katelyn Fund, The Georgia Angels Fund, and the Marshall's Heritage Foundation. W. David Arnold acknowledges funding from NINDS (NS079163-01). We would like to thank Dr. Kolb and Dr. Kissel for interesting discussions and insightful input.

References

- 1.Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995 Jan 13;80(1):155–65. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearn J. Incidence, prevalence, and gene frequency studies of chronic childhood spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Genet. 1978 Dec;15(6):409–13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.15.6.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prior TW, Snyder PJ, Rink BD, et al. Newborn and carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Med Genet A. 2010 Jul;152A(7):1608–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of >72,400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012 Jan;20(1):27–32. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts DF, Chavez J, Court SD. The genetic component in child mortality. Archives of disease in childhood. 1970 Feb;45(239):33–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2009 Aug;10(8):597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S. Natural history in proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Clinical analysis of 445 patients and suggestions for a modification of existing classifications. Archives of neurology. 1995 May;52(5):518–23. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540290108025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowerman M, Murray LM, Beauvais A, Pinheiro B, Kothary R. A critical smn threshold in mice dictates onset of an intermediate spinal muscular atrophy phenotype associated with a distinct neuromuscular junction pathology. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2012 Mar;22(3):263–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piepers S, van den Berg LH, Brugman F, et al. A natural history study of late onset spinal muscular atrophy types 3b and 4. J Neurol. 2008 Sep;255(9):1400–4. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0929-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monani UR, Lorson CL, Parsons DW, et al. A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2. Hum Mol Genet. 1999 Jul;8(7):1177–83. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B. A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 May 25;96(11):6307–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cartegni L, Krainer AR. Disruption of an SF2/ASF-dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat Genet. 2002 Apr;30(4):377–84. doi: 10.1038/ng854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gennarelli M, Lucarelli M, Capon F, et al. Survival motor neuron gene transcript analysis in muscles from spinal muscular atrophy patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Aug 4;213(1):342–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorson CL, Strasswimmer J, Yao JM, et al. SMN oligomerization defect correlates with spinal muscular atrophy severity. Nat Genet. 1998 May;19(1):63–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorson CL, Androphy EJ. An exonic enhancer is required for inclusion of an essential exon in the SMA-determining gene SMN. Hum Mol Genet. 2000 Jan 22;9(2):259–65. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett BG, Munoz E, Tandon A, Kwon DY, Sumner CJ, Fischbeck KH. Regulation of SMN protein stability. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Mar;29(5):1107–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01262-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAndrew PE, Parsons DW, Simard LR, et al. Identification of proximal spinal muscular atrophy carriers and patients by analysis of SMNT and SMNC gene copy number. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Jun;60(6):1411–22. doi: 10.1086/515465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burghes AH. When is a deletion not a deletion? When it is converted. Am J Hum Genet. 1997 Jul;61(1):9–15. doi: 10.1086/513913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrank B, Gotz R, Gunnersen JM, et al. Inactivation of the survival motor neuron gene, a candidate gene for human spinal muscular atrophy, leads to massive cell death in early mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Sep 2;94(18):9920–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monani UR, Sendtner M, Coovert DD, et al. The human centromeric survival motor neuron gene (SMN2) rescues embryonic lethality in Smn(-/-) mice and results in a mouse with spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2000 Feb;Dec;9(3):333–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh-Li HM, Chang JG, Jong YJ, et al. A mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000 Jan;24(1):66–70. doi: 10.1038/71709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prior TW, Krainer AR, Hua Y, et al. A positive modifier of spinal muscular atrophy in the SMN2 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Sep;85(3):408–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vezain M, Saugier-Veber P, Goina E, et al. A rare SMN2 variant in a previously unrecognized composite splicing regulatory element induces exon 7 inclusion and reduces the clinical severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mutat. 2010 Jan;31(1):E1110–25. doi: 10.1002/humu.21173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernal S, Alias L, Barcelo MJ, et al. The c.859G>C variant in the SMN2 gene is associated with types II and III SMA and originates from a common ancestor. J Med Genet. 2010 Sep;47(9):640–2. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.079004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burghes AH, Ingraham SE, Kote-Jarai Z, et al. Linkage mapping of the spinal muscular atrophy gene. Human genetics. 1994 Mar;93(3):305–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00212028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobben JM, van der Steege G, Grootscholten P, de Visser M, Scheffer H, Buys CH. Deletions of the survival motor neuron gene in unaffected siblings of patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 1995 Oct;57(4):805–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahnen E, Forkert R, Marke C, et al. Molecular analysis of candidate genes on chromosome 5q13 in autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy: evidence of homozygous deletions of the SMN gene in unaffected individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 1995 Oct;4(10):1927–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.10.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiDonato CJ, Morgan K, Carpten JD, et al. Association between Ag1-CA alleles and severity of autosomal recessive proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 1994 Dec;55(6):1218–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wirth B, el-Agwany A, Baasner A, et al. Mapping of the spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) gene to a 750-kb interval flanked by two new microsatellites. Eur J Hum Genet. 1995;3(1):56–60. doi: 10.1159/000472274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oprea GE, Krober S, McWhorter ML, et al. Plastin 3 is a protective modifier of autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy. Science. 2008 Apr 25;320(5875):524–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1155085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernal S, Also-Rallo E, Martinez-Hernandez R, et al. Plastin 3 expression in discordant spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) siblings. Neuromuscular disorders : NMD. 2011 Jun;21(6):413–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bebee TW, Gladman JT, Chandler DS. Splicing regulation of the survival motor neuron genes and implications for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. Front Biosci. 2011;15:1191–204. doi: 10.2741/3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellizzoni L. Chaperoning ribonucleoprotein biogenesis in health and disease. EMBO Rep. 2007 Apr;8(4):340–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cifuentes-Diaz C, Frugier T, Tiziano FD, et al. Deletion of murine SMN exon 7 directed to skeletal muscle leads to severe muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 2001 Mar 5;152(5):1107–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitte JM, Davoult B, Roblot N, et al. Deletion of murine Smn exon 7 directed to liver leads to severe defect of liver development associated with iron overload. Am J Pathol. 2004 Nov;165(5):1731–41. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan L, Battle DJ, Yong J, et al. The survival of motor neurons protein determines the capacity for snRNP assembly: biochemical deficiency in spinal muscular atrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Jul;25(13):5543–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5543-5551.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabanella F, Butchbach ME, Saieva L, Carissimi C, Burghes AH, Pellizzoni L. Ribonucleoprotein Assembly Defects Correlate with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Severity and Preferentially Affect a Subset of Spliceosomal snRNPs. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(9):e921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Workman E, Saieva L, Carrel TL, et al. A SMN missense mutation complements SMN2 restoring snRNPs and rescuing SMA mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 Jun 15;18(12):2215–29. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lotti F, Imlach WL, Saieva L, et al. An SMN-dependent U12 splicing event essential for motor circuit function. Cell. 2012 Oct 12;151(2):440–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baumer D, Lee S, Nicholson G, et al. Alternative splicing events are a late feature of pathology in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS Genet. 2009 Dec;5(12):e1000773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruggiu M, McGovern VL, Lotti F, et al. A role for SMN exon 7 splicing in the selective vulnerability of motor neurons in spinal muscular atrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2012 Jan;32(1):126–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06077-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imlach WL, Beck ES, Choi BJ, Lotti F, Pellizzoni L, McCabe BD. SMN is required for sensory-motor circuit function in Drosophila. Cell. 2012 Oct 12;151(2):427–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan YB, Miguel-Aliaga I, Franks C, et al. Neuromuscular defects in a Drosophila survival motor neuron gene mutant. Hum Mol Genet. 2003 Jun 15;12(12):1367–76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mentis GZ, Blivis D, Liu W, et al. Early functional impairment of sensory-motor connectivity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neuron. Feb 10;69(3):453–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gavrilina TO, McGovern VL, Workman E, et al. Neuronal SMN expression corrects spinal muscular atrophy in severe SMA mice while muscle-specific SMN expression has no phenotypic effect. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 Apr;1517(8):1063–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gogliotti RG, Quinlan KA, Barlow CB, Heier CR, Heckman CJ, Didonato CJ. Motor neuron rescue in spinal muscular atrophy mice demonstrates that sensory-motor defects are a consequence, not a cause, of motor neuron dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2012 Mar 14;32(11):3818–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5775-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez TL, Kong L, Wang X, et al. Survival motor neuron protein in motor neurons determines synaptic integrity in spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurosci. 2012 Jun 20;32(25):8703–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0204-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park GH, Maeno-Hikichi Y, Awano T, Landmesser LT, Monani UR. Reduced survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein in motor neuronal progenitors functions cell autonomously to cause spinal muscular atrophy in model mice expressing the human centromeric (SMN2) gene. J Neurosci. Sep 8;30(36):12005–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2208-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowerman M, Murray LM, Boyer JG, Anderson CL, Kothary R. Fasudil improves survival and promotes skeletal muscle development in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. BMC medicine. 2012;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009 Jan 15;457(7227):277–80. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossoll W, Jablonka S, Andreassi C, et al. Smn, the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene product, modulates axon growth and localization of beta-actin mRNA in growth cones of motoneurons. J Cell Biol. 2003 Nov 24;163(4):801–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200304128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McWhorter ML, Monani UR, Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Knockdown of the survival motor neuron (Smn) protein in zebrafish causes defects in motor axon outgrowth and pathfinding. J Cell Biol. 2003 Sep 1;162(5):919–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossoll W, Bassell GJ. Spinal muscular atrophy and a model for survival of motor neuron protein function in axonal ribonucleoprotein complexes. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2009;48:289–326. doi: 10.1007/400_2009_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.di Penta A, Mercaldo V, Florenzano F, et al. Dendritic LSm1/CBP80-mRNPs mark the early steps of transport commitment and translational control. J Cell Biol. 2009 Feb 9;184(3):423–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Todd AG, Lin H, Ebert AD, Liu Y, Androphy EJ. COPI transport complexes bind to specific RNAs in neuronal cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Feb 15;22(4):729–36. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peter CJ, Evans M, Thayanithy V, et al. The COPI vesicle complex binds and moves with survival motor neuron within axons. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 May 1;20(9):1701–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hubers L, Valderrama-Carvajal H, Laframboise J, Timbers J, Sanchez G, Cote J. HuD interacts with survival motor neuron protein and can rescue spinal muscular atrophy-like neuronal defects. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Feb 1;20(3):553–79. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fallini C, Zhang H, Su Y, et al. The survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein interacts with the mRNA-binding protein HuD and regulates localization of poly(A) mRNA in primary motor neuron axons. J Neurosci. 2011 Mar 9;31(10):3914–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3631-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, et al. Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy. J Child Neurol. 2007 Aug;22(8):1027–49. doi: 10.1177/0883073807305788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Russman BS, Iannaccone ST, Samaha FJ. A phase 1 trial of riluzole in spinal muscular atrophy. Arch Neurol. 2003 Nov;60(11):1601–3. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.11.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merlini L, Solari A, Vita G, et al. Role of gabapentin in spinal muscular atrophy: results of a multicenter, randomized Italian study. J Child Neurol. 2003 Aug;18(8):537–41. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180080501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mercuri E, Bertini E, Messina S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of phenylbutyrate in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2007 Jan 2;68(1):51–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249142.82285.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang WC, Yuo CY, Chang JG, et al. The effect of hydroxyurea in spinal muscular atrophy cells and patients. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2008 May 15;268(1-2):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swoboda KJ, Scott CB, Reyna SP, et al. Phase II open label study of valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swoboda KJ, Scott CB, Crawford TO, et al. SMA CARNI-VAL trial part I: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of L-carnitine and valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kissel JT, Scott CB, Reyna SP, et al. SMA CARNIVAL TRIAL PART II: a prospective, single-armed trial of L-carnitine and valproic acid in ambulatory children with spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kissel JT, Elsheikh B, King WM, et al. SMA VALIANT Trial: A prospective, double-blind, placebo controlled trial of valproic acid in ambulatory adults with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle & nerve. 2013 May 16; doi: 10.1002/mus.23904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Angelozzi C, Borgo F, Tiziano FD, Martella A, Neri G, Brahe C. Salbutamol increases SMN mRNA and protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy cells. J Med Genet 2007. 2007 Oct 11;45(1):29–31. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051177. 2008 Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pane M, Staccioli S, Messina S, et al. Daily salbutamol in young patients with SMA type II. Neuromuscular disorders NMD. 2008 Jul;18(7):536–40. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Le TT, McGovern VL, Alwine IE, et al. Temporal requirement for high SMN expression in SMA mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011 Sep 15;20(18):3578–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr275. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lutz CM, Kariya S, Patruni S, et al. Postsymptomatic restoration of SMN rescues the disease phenotype in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(8):3029–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI57291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corti S, Nizzardo M, Nardini M, et al. Neural stem cell transplantation can ameliorate the phenotype of a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(10):3316–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI35432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Corti S, Nizzardo M, Nardini M, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem cells improve spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in mice. Brain. 2010 Feb 1;133(2):465–81. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp318. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Corti S, Nizzardo M, Simone C, et al. Genetic correction of human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Dec 19;4(165):165ra2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Le TT, McGovern VL, Alwine IE, et al. Temporal requirement for high SMN expression in SMA mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Sep 15;20(18):3578–91. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Foust KD, Wang X, McGovern VL, et al. Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat Biotech. 2010;28(3):271–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Azzouz M, Le T, Ralph GS, et al. Lentivector-mediated SMN replacement in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(12):1726–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI22922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Valori CF, Ning K, Wyles M, et al. Systemic Delivery of scAAV9 Expressing SMN Prolongs Survival in a Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Science Translational Medicine. 2010 Jun 9;2(35):35ra42. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000830. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Passini MA, Bu J, Roskelley EM, et al. CNS-targeted gene therapy improves survival and motor function in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(4):1253–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI41615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dominguez E, Marais T, Chatauret N, et al. Intravenous scAAV9 delivery of a codon-optimized SMN1 sequence rescues SMA mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011 Feb 15;20(4):681–93. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq514. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Glascock JJ, Shababi M, Wetz MJ, Krogman MM, Lorson CL. Direct central nervous system delivery provides enhanced protection following vector mediated gene replacement in a severe model of spinal muscular atrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commune. 2012 Jan 6;417(1):376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S, Besse A, Roda M, et al. Intramuscular scAAV9-SMN injection mediates widespread gene delivery to the spinal cord and decreases disease severity in SMA mice. Mol Ther. 2013 Feb;21(2):282–90. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nature biotechnology. 2009 Jan;27(1):59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duque S, Joussemet B, Riviere C, et al. Intravenous administration of self-complementary AAV9 enables transgene delivery to adult motor neurons. Mol Ther. 2009 Jul;17(7):1187–96. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bevan AK, Duque S, Foust KD, et al. Systemic gene delivery in large species for targeting spinal cord, brain, and peripheral tissues for pediatric disorders. Mol Ther. 2011 Nov;19(11):1971–80. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Federici T, Taub JS, Baum GR, et al. Robust spinal motor neuron transduction following intrathecal delivery of AAV9 in pigs. Gene Ther. 2012 Aug;19(8):852–9. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gray SJ, Nagabhushan Kalburgi S, McCown TJ, Jude Samulski R. Global CNS gene delivery and evasion of anti-AAV-neutralizing antibodies by intrathecal AAV administration in non-human primates. Gene Ther. 2013 Apr;20(4):450–9. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Porensky PN, Burghes AH. Antisense oligonucleotides for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2013 May;24(5):489–98. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Porensky PN, Mitrpant C, McGovern VL, et al. A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in the mouse. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011 Dec 20; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr600. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou H, Janghra N, Mitrpant C, et al. A novel morpholino oligomer targeting ISS-N1 improves rescue of severe spinal muscular atrophy transgenic mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2013 Mar;24(3):331–42. doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mitrpant C, Porensky P, Zhou H, et al. Improved Antisense Oligonucleotide Design to Suppress Aberrant SMN2 Gene Transcript Processing: Towards a Treatment for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hua Y, Sahashi K, Rigo F, et al. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature. 2011;478(7367):123–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baughan TD, Dickson A, Osman EY, Lorson CL. Delivery of bifunctional RNAs that target an intronic repressor and increase SMN levels in an animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 May 1;18(9):1600–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Williams JH, Schray RC, Patterson CA, Ayitey SO, Tallent MK, Lutz GJ. Oligonucleotide-mediated survival of motor neuron protein expression in CNS improves phenotype in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of neuroscience the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009 Jun 17;29(24):7633–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0950-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Passini MA, Bu J, Richards AM, et al. Antisense Oligonucleotides Delivered to the Mouse CNS Ameliorate Symptoms of Severe Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Science Translational Medicine. 2011 Mar 2;3(72):72ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001777. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Porensky PN, Mitrpant C, McGovern VL, et al. A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2012 Apr 1;21(7):1625–38. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Claudia Chiriboga KS, Basil Darras, Susan Iannaccone, Jacqueline Montes, Heather Allen, Rebecca Parad, Shanda Johnson, Darryl De Vivo, Daniel Norris, Katie Alexander, Frank Bennett, Kathie Bishop. Results of an Open-Label Escalating Dose Study To Assess the Safety Tolerability Does Range Finding of a Single Intrathecal Dose of ISIS-SMNRx in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. AAN Meeting Abstracts. 2013;80(S36.002) [Google Scholar]

- 98.Butchbach MER, Singh J, Þorsteinsdóttir M, et al. Effects of 2,4-diaminoquinazoline derivatives on SMN expression and phenotype in a mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010 Feb 1;19(3):454–67. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp510. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gogliotti RG, Cardona H, Singh J, et al. The DcpS inhibitor RG3039 improves survival, function and motor unit pathologies in two SMA mouse models. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013 Jun 4; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt258. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Van Meerbeke JP, Gibbs RM, Plasterer HL, et al. The DcpS inhibitor RG3039 improves motor function in SMA mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013 May 31; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt257. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Montes J, Gordon AM, Pandya S, De Vivo DC, Kaufmann P. Clinical Outcome Measures in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Journal of child neurology. 2009;24(8):968–78. doi: 10.1177/0883073809332702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cano SJ, Mayhew A, Glanzman AM, et al. Rasch analysis of clinical outcome measures in spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle & nerve. 2013:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/mus.23937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Crawford TO, Paushkin SV, Kobayashi DT, et al. Evaluation of SMN protein, transcript, and copy number in the biomarkers for spinal muscular atrophy (BforSMA) clinical study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Finkel RS, Crawford TO, Swoboda KJ, et al. Candidate proteins, metabolites and transcripts in the Biomarkers for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (BforSMA) clinical study. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sumner CJ, Kolb SJ, Harmison GG, et al. SMN mRNA and protein levels in peripheral blood: biomarkers for SMA clinical trials. Neurology. 2006 Apr 11;66(7):1067–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201929.56928.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kong L, Wang X, Choe DW, et al. Impaired Synaptic Vesicle Release and Immaturity of Neuromuscular Junctions in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009 Jan 21;29(3):842–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4434-08.2009. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ling KKY, Lin MY, Zingg B, Feng Z, Ko CP. Synaptic Defects in the Spinal and Neuromuscular Circuitry in a Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e15457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wadman RI, Vrancken AF, van den Berg LH, van der Pol WL. Dysfunction of the neuromuscular junction in spinal muscular atrophy types 2 and 3. Neurology. 2012;79(20):2050–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182749eca. 2012 Nov 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Swoboda KJ, Prior TW, Scott CB, et al. Natural history of denervation in SMA: Relation to age, SMN2 copy number, and function. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57(5):704–12. doi: 10.1002/ana.20473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lewelt A, Krosschell KJ, Scott C, et al. Compound muscle action potential and motor function in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle & nerve. 2010;42(5):703–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Finkel RS. Electrophysiological and motor function scale association in a pre-symptomatic infant with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2013;23(2):112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rutkove SB, Gregas MC, Darras BT. Electrical impedance myography in spinal muscular atrophy: a longitudinal study. Muscle & nerve. 2012 May;45(5):642–7. doi: 10.1002/mus.23233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shababi M, Habibi J, Ma L, Glascock JJ, Sowers JR, Lorson CL. Partial restoration of cardiovascular defects in a rescued severe model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012 May;52(5):1074–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Finkel RS. Electrophysiological and motor function scale association in a pre-symptomatic infant with spinal muscular atrophy type I. Neuromuscular disorders NMD. 2013 Feb;23(2):112–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S, Besse A, Roda M, et al. Intramuscular scAAV9-SMN Injection Mediates Widespread Gene Delivery to the Spinal Cord and Decreases Disease Severity in SMA Mice. Mol Ther. 2013;21(2):282–90. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Coady TH, Lorson CL. Trans-splicing-mediated improvement in a severe mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official. journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010 Jan 6;30(1):126–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4489-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shababi M, Glascock J, Lorson CL. Combination of SMN trans-splicing and a neurotrophic factor increases the life span and body mass in a severe model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2011 Feb;22(2):135–44. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Riessland M, Ackermann B, Forster A, et al. SAHA ameliorates the SMA phenotype in two mouse models for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Apr 15;19(8):1492–506. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Avila AM, Burnett BG, Taye AA, et al. Trichostatin A increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin Invest. 2007 Mar;117(3):659–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI29562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Narver HL, Kong L, Burnett BG, et al. Sustained improvement of spinal muscular atrophy mice treated with trichostatin A plus nutrition. Ann Neurol. 2008 Oct;64(4):465–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.21449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Farooq F, Abadia-Molina F, Mackenzie D, et al. Celecoxib increases SMN and survival in a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model via p38 pathway activation. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 May 10; doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kwon DY, Motley WW, Fischbeck KH, Burnett BG. Increasing expression and decreasing degradation of SMN ameliorate the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2011 Sep 15;20(18):3667–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mattis VB, Ebert AD, Fosso MY, Chang CW, Lorson CL. Delivery of a read-through inducing compound, TC007, lessens the severity of a spinal muscular atrophy animal model. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009 Oct 15;18(20):3906–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp333. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bowerman M, Beauvais A, Anderson CL, Kothary R. Rho-kinase inactivation prolongs survival of an intermediate SMA mouse model. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 Apr 15;19(8):1468–78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cherry JJ, Osman EY, Evans MC, et al. Enhancement of SMN protein levels in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy using novel drug-like compounds. EMBO molecular medicine. 2013 Jul;5(7):1103–18. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]