Abstract

Urogenital atrophy affects the lower urinary and genital tracts and is responsible for urinary, genital, and sexual symptoms. The accurate identification, measurement, and documentation of symptoms are limited by the absence of reliable and valid instruments. The Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire was developed to allow self-reporting of symptoms and to provide clinicians and researchers an instrument to identify, measure, and document indicators of urogenital atrophy. A pilot study (n = 30) measured test-retest reliability (p < .05) of the instrument. Subsequently, a survey of women with (n = 168) and without breast cancer (n = 166) was conducted using the Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire, Female Sexual Function Instrument, and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Breast, Endocrine Scale. Exploratory factor analysis (KMO 0.774; Bartlett’s test of sphericity 0.000) indicated moderate-high relatedness of items. Concurrent (p > .01) and divergent validity (p < .000) were established. A questionnaire resulted that enables women, regardless of sexual orientation, partner status, and levels of sexual activity to accurately report symptoms.

Keywords: atrophic vaginitis, urogenital atrophy, sexuality, vaginal dryness, breast cancer, incontinence

Urogenital atrophy affects the lower urinary and genital tracts and can be responsible for a cluster of urinary, genital, and sexual symptoms that are common in breast cancer survivors due to chemotherapy-induced menopause and negative effects of treatment (Lester & Bernhard, 2009). The accurate identification, measurement, and documentation of these treatment-induced symptoms are limited by the absence of a reliable and valid instrument. A review of existing quality-of-life, sexual functioning, and menopausal instruments revealed multiple items that measured isolated symptoms related to urogenital atrophy but did not provide a comprehensive instrument. The Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire (UAQ) was developed to allow women to self-report urologic, genital, and sexual symptoms, and provide clinicians and researchers an instrument to identify, measure, and document indicators of urogenital atrophy.

Urogenital Atrophy Symptoms and Related Self-Report Instruments

Breast cancer is the most prevalent type of cancer among women in the United States, with an estimated 5 million breast cancer survivors (Jemal, Siegel, Xu, & Ward, 2010). Unpleasant symptoms such as urogenital atrophy are often experienced secondary to the consequences of diagnosis and the life-extending treatments of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, hormone agonists, and ovarian ablation (Kelley, 2007; Willhite & O’Connell, 2001). These symptoms, though common in the general postmenopausal female population, are often more prevalent and severe in women treated for breast cancer (Conde et al., 2005; Lester, 2008; Zibecchi, Greendale, & Ganz, 2003).

Unpleasant symptoms of urogenital atrophy and physiologic influences of breast cancer treatments are important research areas in breast cancer survivorship. These distressing symptoms are often unidentified and untreated by health care providers, thus potentially impairing sexual quality of life (Avis, Crawford, & Manuel, 2005; McKenna, Whalley, Renck-Hooper, Carlin, & Doward, 1999; Zibecchi et al., 2003). Significant statistical differences exist between self-reported symptoms and observed clinical signs in studies related to measurement of urogenital atrophy in healthy women, indicating potential assessment bias that could interfere with beneficial interventions (Willhite & O’Connell, 2001).

Symptoms related to urogenital atrophy are often measured by instruments that focus on sexual function as an outcome, assuming current sexual activity in a heterosexual relationship (Speer et al., 2005). These instruments may not accurately measure women who are not sexually active, or not heterosexual. Few instruments are validated (Daker-White, 2002), and even fewer measure urogenital symptoms in women with breast cancer (Barni & Mondin, 1997; Kirkova et al., 2006). A concise, yet comprehensive, instrument to measure the urologic, genital, and sexual aspects of urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors was not identified in the literature.

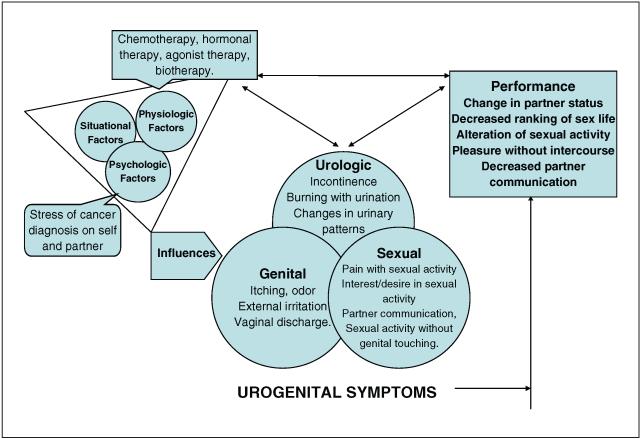

The theory of unpleasant symptoms (TOUS) provides a conceptual frame-work to explore the symptomatic phenomena of urogenital atrophy (Figure 1). The TOUS is a middle-range nursing theory (Lenz & Pugh, 2003) that enables a thorough examination of the subjective, self-reported symptoms related to urogenital atrophy with identification of the cluster of urologic, genital, and sexual symptoms as experienced by women. Central to the model, these multidimensional components focus on symptom occurrence, intensity, timing, level of distress perceived, and quality. In addition, the model guides exploration of psychologic, physiologic, and situational influence(s), potential interaction among the symptoms, and consequences on performance, although these interactions and study findings are not fully described in this article.

Figure 1.

Unpleasant symptoms related to urogenital atrophy in the breast cancer survivor

The TOUS focuses on the subjective symptoms as perceived by the patient, as opposed to objective symptoms that are unilaterally observed by the clinician. The practitioner can be more aware of the patient’s experience and avoid clinical decision making based on objective measurement alone, which may be an inaccurate representation of the clinical condition. Evaluation of the effect of interventions is most meaningful with inclusion of the symptom experience (Barni & Mondin, 1997; Ganz, Desmond, Belin, Meyerowitz, & Rowland, 1999).

Urogenital atrophy is an inflammatory condition of the lower genitalia that causes pain and discomfort as a result of dryness and decreased elasticity (Kelley, 2007). Decreases in systemic estrogen over time such as those observed in the menopause transition can result in estrogen deprivation to these tissues. The normal trajectory of estrogen deprivation can be exacerbated by an oophorectomy and systemic drug interventions, including cancer treatment. This loss of estrogen leads to degeneration of tissues, with decreases in genitalia size, blood flow, and vaginal secretions; loss of elasticity; thinning of tissues; increase in vaginal pH; and overall genital atrophy (Kelley, 2007; Willhite & O’Connell, 2001).

A number of self-report instruments that measure menopausal symptoms and sexuality exist in the literature. A systematic review was necessary to determine the content of these instruments, the appropriateness for breast cancer survivors, and the feasibility for use in the clinical setting to gather information about the urologic, genital, and sexual symptoms of urogenital atrophy. Instruments that measured genital changes such as vaginitis (Davidson & Grant, 2004; Grant & Davidson, 1984; Lowe & Ryan-Wenger, 2000) and/or urinary incontinence (Coyne et al., 2002) were identified; instruments measuring sexuality and sexual functioning were noted. DeRogatis (2008) described six contemporary self-report instruments for females, although none were designed for women with cancer. The Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire (FSAQ) as described by Atkins and Fallowfield (2007) was developed to study the effect of long-term hormonal therapy on sexual functioning in women at increased risk of breast cancer development. The FSAQ incorporated several genital and sexual items in the instrument; urinary items were absent.

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Therapy, Breast, Endocrine Scale (FACT-B, ES), a quality-of-life instrument for the self-reporting of symptoms in women with breast cancer included several items specific to genital and sexual symptoms; it was lengthy with 54 items, and urologic questions were absent (Fallowfield, Leaity, Howell, Benson, & Cella, 1999). The Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) symptom scales, created to record a variety of self-reported symptoms of postmenopausal women at increased risk for breast cancer development, were documented in several versions: (a) original BCPT (52 items; Stanton, Bernaards, & Ganz, 2005), (b) modified version (43 items; Alfano et al., 2006), and (c) abbreviated 16-item symptom scale of common menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors (Alfano et al., 2006). Several items from these instruments were helpful to describe urogenital atrophy, but were not inclusive of the range of urologic, genital, and sexual symptoms. Psychometric data for the initial versions were sparse.

In the absence of a valid and reliable instrument in the literature, a new instrument was proposed. The development of a concise self-report instrument(s) was essential to fully document the relevant urinary, genital, and sexual symptoms in the clinical and research settings for all women regardless of partner status, sexual orientation, and/or level of sexual practices.

Method and Results

An exploratory, descriptive study was used to develop a self-report instrument to characterize symptoms related to urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors. The study was conducted with approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Ohio State University and in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983.

Instrument Development

Item identification

To generate items, an extensive review of the literature was performed using Cochrane Evidence-Based Medical Reviews (EBMR), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Health & Psychosocial Instruments (HAPI), MD Consult, MicroMedex, Ovid Medline, PubMed, and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI). Keywords included atrophy, urogenital, urogenital atrophy, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, incontinence, stress incontinence, sexuality, sexual dysfunction, menopause, perimenopause, chemo-induced menopause, and breast cancer. Informal face-to-face conversations occurred in the clinical setting between the researcher and postmenopausal women aged 35 years and older, with and without breast cancer, to generate items that represented experienced symptoms related to urogenital atrophy. Symptoms were thematically categorized into three domains of items for the instrument: urinary, genital, and sexual.

Urinary symptoms included burning on skin with urination, dysuria/burning with urination, cough/sneeze/laugh incontinence, incontinence for no reason, embarrassment with incontinence, urinary urgency, urinary urge incontinence, nocturia, incomplete emptying, and night-time frequency (Coyne et al., 2002; Kelley, 2007; Willhite & O’Connell, 2001). Genital symptoms included external genital irritation with toilet tissue and/or clothing, genital tenderness, unpleasant odor from genitals, genital itching and/or swelling, vaginal bleeding other than menstruation, vaginal dryness and/or itching, unpleasant vaginal odor, and white/creamy and/or yellow/greenish vaginal discharge (Boekhout, Beijnen, & Schellens, 2006; Conde et al., 2005; Gupta et al., 2006; Kelley, 2007).

Sexual symptoms included external genital burning with urination, swelling after sexual activity (SA), negative thoughts of SA secondary to external genital tenderness, vaginal spotting/bleeding after SA, introitus pain with SA, pain inside vagina with penetration, intolerance of penetration secondary to pain, presence/absence of vaginal lubrication with SA, use of lubricant with SA and/or secondary to pain, desire and/or interest in SA, initiation of SA, satisfaction with vaginal penetration with SA, satisfaction with SA without vaginal penetration and/or genital touching, worry about SA secondary to genital and/or vaginal pain, burning with urination after SA, worry about pregnancy, happiness with sex life, and ability to talk with partner (Broeckel, Thors, Jacobsen, Small, & Cox, 2002; Cella & Fallowfield, 2008; Ganz et al., 1999; Huber, Ramnarace, & McCaffrey, 2006; Speer et al., 2005).

Face validity

An item pool of norm-referenced items pertinent to the selfreport of urinary (10 items), genital (12 items), and sexual symptoms (23 items) was created. Response options were based on frequency of symptom experiences and scored on an ordinal scale: 1 = none of the time to 4 = all of the time. A score of 5 = no sexual activity was an option for questions strictly related to vaginal penetration. Patients and nursing staff provided face validity of the draft Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire, with attention to grammar, syntax, organization, appropriateness, and logical flow.

Content validity

A panel of nine breast cancer experts was selected for determination of face and content validity, including professionals from medical and surgical oncology, gynecology, advanced nursing practice, pharmacy, social work, psychology, and sexual therapy. Panel members were asked to score the draft questionnaire to determine the association of items to the construct of urogenital atrophy. Content validity was calculated in a two-step method with calculations in the developmental and judgment stages (Lynn, 1986). The summary content validity index (CVI) score was 1.0 on individual items and 1.0 for the overall tool.

Pilot Study

In May 2007, a pilot study was conducted using a convenience sample of postmenopausal breast cancer survivors (n = 30) with complaints of vaginal dryness and/or dyspareunia to test the questionnaire for consideration of readability, answer options, ease of administration, and clarity, and a beginning assessment of validity. Inclusion criteria were aged 18 years or older, female, had a diagnosis of breast cancer, were able to speak and read English, willing to participate in study, and had completed written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were women attending clinic for the first time; history of pelvic, perineal, or intravaginal radiation therapy; and/or previous history of other cancer(s).

Instruments

Four self-report instruments were used in the pilot study: (a) demographic instrument, (b) Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire, (c) Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and (d) Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Breast with Endocrine subscale (FACT-B, ES). The demographic instrument included nearly 100 data points that described physical, obstetric, gynecologic, and urinary histories, daily fluid and caffeine intakes, partner status, ranking of sexual life/satisfaction, medication history, and breast cancer treatment.

The Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire consisted of 45 items that described potential symptoms related to pain/discomfort, function, satisfaction, and urogenital quality of life from the urinary, genital, and sexual domains. Participants were asked to evaluate symptoms as experienced in the previous 4 weeks, and to select a response option from the 4-point scale described above. Again, 5 = no sexual activity was an option for items strictly related to vaginal penetration, but these scores were not included in the analyses. Selected item responses were reverse-scored to provide a congruent scale in which high scores represent high symptomatology.

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast Symptom Index (FACT-B, Version 4) with the Endocrine scale (ES) consists of 54 multidimensional items on a 5-point scale (1 representing not at all and 5 representing very much). The FACT-B, ES was designed to measure quality-of-life indicators in breast cancer survivors receiving endocrine therapy(s), with subscales of physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, breast cancer-specific, and endocrine treatment-related symptoms and concerns. Psychometric properties include internal consistency coefficients with Cronbach’s alpha .79, test-retest reliability coefficients of .93, sensitivity over time (p < .0001) and discriminant validity (p < .001; Fallowfield et al., 1999). The FACT-B, ES was used in the current study to establish convergent validity between items from the emotional and ES subscales and the urogenital atrophy instrument.

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) consists of 19 self-report items on a 5-point scale (ranging from almost never or never or very low/not at all to almost always or always or very high with answer options of no sexual activity or did not attempt intercourse). The FSFI was designed to measure sexual functioning in females, irrespective of gender, menopausal status, or level of sexual activity as related to subscales of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. Psychometric properties include internal consistency coefficients with Cronbach’s alpha .89 to .97, test–retest reliability coefficients of .79 to .86, and discriminant (p ≤ .001) and divergent (r = .53/.22) measures of validity (Rosen et al., 2000). The FSFI was used in the current study to establish convergent validity between the FSFI and sexual items from the urogenital atrophy instrument, and divergent validity between the FSFI and urologic items from the urogenital atrophy instrument.

After obtaining written informed consent, participants completed the selfreport study packet containing approximately 218 items at their clinic visit, with an average completion time of 30 to 40 min. To protect patient privacy, questionnaires were marked only with the participant’s study number. Electronic chart reviews were performed by study personnel to validate urologic, obstetric, and gynecologic history, breast cancer stage and treatment, and medication usage. All instruments were in Tele-Form® format and electronically scored in the Ohio State University General Clinical Research Center (GCRC). Data were stored on an encrypted Excel® file for import into SPSS®, Version 16.0.

Test-retest measure of reliability

To evaluate the stability of the scale, the questionnaire was mailed to each participant 7 to 10 days after their visit. Instructions were included to answer the items based on symptoms experienced in the previous 1 month. Twenty retest questionnaires were returned, indicating a 67% return rate. Of the participants that did not return the retest questionnaire, one patient died, two were hospitalized for neutrapenic fever, two underwent surgery, one returned a blank instrument, and four were considered lost to follow-up.

The Spearman coefficient was used to estimate test-retest stability of items on the urogenital questionnaire (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Statistically significant correlations were observed with 31/45 items at the .05 or .01 levels of significance. Limitations of this pilot study included the small sample size (n = 30) and cumulative alpha error from multiple comparisons. Minor revisions were made to the urogenital atrophy questionnaire; a psychometric study of the instrument was planned as the next phase of the study.

Testing of Revised Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire

The second phase of the study occurred in 2007-2008, and consisted of a convenience sample (N = 334) of women receiving treatment or long-term follow-up at an NCI-affiliated comprehensive breast health center and/or obstetrics/gynecology offices, located in central Ohio (Table 1). A power analysis was performed for t tests of differences between breast cancer survivors and women without breast cancer. The effect size was estimated from pilot study data on breast cancer survivors, and the investigator’s clinical experience with women without breast cancer. A one-tailed alpha of .05, power = .80, and a medium effect size, d = .50, were used to determine that at least 50 participants per group were needed to study differences related to urogenital atrophy between breast cancer survivors and women without breast cancer within the urologic, genital, and sexual domains. Therefore, based on a 2 × 3 correlational matrix with inclusion of a small dropout percentage, 167 women without breast cancer, and 167 breast cancer survivors were sought.

Table 1.

Selected Demographics From Study Sample

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Women with breast cancer | 198 | 54 |

| Pilot study | 30 | |

| Larger study | 168 | |

| Women without breast cancer | 166 | 46 |

| Age | ||

| 20-29 | 6 | 1.6 |

| 30-39 | 33 | 9.1 |

| 40-49 | 93 | 25.5 |

| 50-59 | 133 | 36.5 |

| 60-69 | 72 | 19.8 |

| 70-79 | 23 | 6.3 |

| 80-89 | 4 | 1.1 |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Native Alaskan | 8 | 2.2 |

| African American | 6 | 1.6 |

| Asian | 20 | 5.5 |

| Caucasian | 321 | 88.2 |

| Other | 7 | 1.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 9 | 2.5 |

| Non-Hispanic | 354 | 97.5 |

| Level of education | ||

| Grade 4-8 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Some high school | 7 | 2.0 |

| High school graduate | 104 | 29.1 |

| Technical school | 31 | 8.7 |

| College | 121 | 33.8 |

| Post graduate | 94 | 26.3 |

| Household income in dollars | ||

| 0-14,999 | 12 | 2.3 |

| 15,000-29,999 | 17 | 5.0 |

| 30,000-44,999 | 24 | 7.0 |

| 45,000-59,999 | 32 | 9.3 |

| 60,000-74,999 | 52 | 15.2 |

| 75,000-89,999 | 50 | 14.6 |

| 90,000-104,999 | 145 | 42.3 |

| 105,000-1 19,999 | 11 | 3.2 |

| >120,000 | 0 | 0.0 |

Inclusion criteria were the same as in the pilot study. A heterogenous sample was sought to create an instrument that could detect symptoms of urogenital atrophy across the spectrum with comparisons to age, menopausal status, and breast cancer history. Of the women qualified to participate in the study, 334/346 women provided consent, with only 12 women choosing not to participate. The sample included 168 breast cancer survivors from medical and surgical oncology clinics and 166 women without breast cancer from mammography, gynecology, and nonmalignant breast clinics (Table 1).

Instruments

The instruments included the (a) demographic instrument; (b) Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire; (c) FACT-B, ES; and (d) FSFI as described in the pilot study above. The latter two instruments were selected for analysis of concurrent and divergent validity. The study procedure remained the same as in the pilot study, with the exception that the retest instrument was not administered.

Reliability measures

The domain sampling model, a linear statistical model, was used to evaluate the internal consistency reliability of items in the Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire (Munro, 2005). Pearson correlation coefficient r was used to estimate item–total and item-item correlations between the 10 urinary items (Table 2), the 12 genital items (Table 3), and the 23 sexual items (Table 4) with statistical significance at the .05 and .01 levels.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Matrix of Urinary Items From the Urogenital Atrophy Instrument

| Burning After Urination |

Urethral Burning After Urination |

Incontinence, With Sneeze or Laugh |

Incontinence, No Reason |

Incontinence, Embarrassment |

Incontinence, Urge |

Leakage, Urge |

Nocturnal Urination |

Incomplete Emptying |

Daytime Frequency |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning after urination |

1 | |||||||||

| Urethral burning after urination |

0.593** | 1 | ||||||||

| Incontinence, with sneeze or laugh |

0.078 | 0.070 | 1 | |||||||

| Incontinence, no reason |

0.021 | 0.042 | 0.475** | 1 | ||||||

| Incontinence, embarrassment |

0.142** | 0.033 | 0.523** | 0.472** | 1 | |||||

| Incontinence, urge |

0.084 | 0.114** | 0.412** | 0.420** | 0.391** | 1 | ||||

| Leakage, urge | 0.094 | 0.099 | 0.506** | 0.489** | 0.461** | 0.643** | 1 | |||

| Nocturnal urination |

0.182** | 0.170** | 0.186** | 0.225** | 0.183** | 0.318** | 0.222** | 1 | ||

| Incomplete emptying |

0.117* | 0.031 | 0.238** | 0.262** | 0.244** | 0.221** | 0.187** | 0.215** | 1 | |

| Daytime frequency |

0.129* | 0.089 | 0.256** | 0.304** | 0.207** | 0.303** | 0.282** | 0.275** | 0.365** | 1 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlation Matrix of Genital Items From the Urogenital Atrophy Instrument

| Irritation With Toilet Tissue |

Irritation With Clothing |

External Genital Tenderness |

External Genital Odor |

External Genital Itching |

External Genital Swelling |

Vaginal Bleeding |

Vaginal Dryness |

Vaginal Itching |

Vaginal Odor |

Vaginal Creamy Discharge |

Vaginal Yellow/ Greenish Discharge |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritation with toilet tissue |

1 | |||||||||||

| Irritation with clothing | .387** | 1 | ||||||||||

| External genital tenderness |

.518** | .361** | 1 | |||||||||

| External genital odor | .293** | .148** | .242** | 1 | ||||||||

| External genital itching | .292** | .257** | .321** | .363** | 1 | |||||||

| External genital swelling | .292** | .274** | .303** | .256** | .350** | 1 | ||||||

| Vaginal bleeding | .059 | .009 | .123* | −.0350 | .086 | .061 | 1 | |||||

| Vaginal dryness | .168* | .057 | .158** | .125* | .060 | .088 | −.077 | 1 | ||||

| Vaginal itching | .239** | .201** | .235** | .346** | .621** | .290** | .063 | .181** | 1 | |||

| Vaginal odor | .222** | .129** | .218** | .695** | .246** | .275** | .030 | .143** | .391** | 1 | ||

| Vaginal creamy discharge |

.092 | .148** | .189** | .310** | .204** | .233** | .051 | −.083 | .163** | .351** | 1 | |

| Vaginal yellow/greenish discharge |

.067 | .097 | .062 | .175** | .080 | .144** | .010 | .027 | .142** | .231** | .242** | 1 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 4.

Pearson Correlation Matrix of Sexual Items in the Urogenital Instrument

| External genital, burning with sex |

External genital, negative thoughts about sexual act |

External genital, swelling after sexual act |

External genital, burning after urination, sex |

Bleeding after sex or penetration |

Vaginal (introitus) pain with sex |

Vaginal (inside) pain with sex |

Vaginal, intolerance of penetration secondary to pain |

Lubrication enough for sex |

Lubricant use for sex, like to |

Lubricant use for sex, because of pain |

Desire sexual activity |

Initiate sexual activity |

Interest in sexual activity |

Sex, with vaginal penetration satisfying |

Sex, without vaginal penetration satisfying |

Sex, without genital touching satisfying |

Sex, negative thoughts secondary to pain |

Sex with vaginal penetration, negative thoughts secondary to pain |

Sex, burning with urination |

Pregnancy, worry |

Sex life, happy with |

Partner, talk with, about sex |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External genital, burning with sex |

1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| External genital, negative thoughts about sexual act |

.520** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| External genital, swelling after sexual act |

.457** | .408** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| External genital, burning after urination, sex |

.697** | .545** | .478** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bleeding after sex or penetration |

.256** | .215** | .260** | .182** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal (introitus) pain with sex |

.423** | .522** | .276** | .452** | .226** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal (inside) pain with sex |

.380** | .460** | .351** | .472** | .208** | .731** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Vaginal, intolerance of penetration secondary to pain |

.329** | .540** | .371** | .431** | .265** | .687** | .719** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Lubrication enough for sex |

.203** | .147** | .113 | .246** | .026 | .329** | .351** | .209** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Lubricant use for sex, like to |

−.094 | .017 | .026 | −.102 | .056 | −.030 | −.041 | .003 | −.243** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Lubricant use for sex,because of pain |

.369** | .362* | .268** | .401** | .204** | .597** | .614** | .530** | .500** | −.213** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Desire sexual activity |

.138** | .144** | .055 | .169** | −.015 | .329** | .305** | .258** | −.038 | .052 | .263** | 1 | |||||||||||

| Initiate sexual activity |

.116* | .204** | −.004 | .134* | .060 | .163** | .153* | .116 | .060 | .042 | −.143* | .550** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Interest in sexual activity |

.136* | .132* | .069 | .159** | .072 | .255** | .248** | .226** | −.011 | −.025 | .224** | .847* | .549** | 1 | |||||||||

| Sex, with vaginal penetration satisfying |

.171** | .238** | .135* | .166** | .108 | .380** | .393** | .332** | .276** | .096 | .240** | .575** | .377** | .589* | 1 | ||||||||

| Sex, without vaginal penetration satisfying |

.026 | .056 | −.074 | .080 | .032 | .066 | −.004 | −.080 | .258* | .007 | .102 | .344** | .334** | .350** | .287** | 1 | |||||||

| Sex, without genital touching satisfying |

.049 | −.019 | .035 | .063 | .024 | .048 | .079 | .058 | .111 | .010 | .046 | .237** | .151* | .229** | .296** | .396** | 1 | ||||||

| Sex, negative thoughts secondary to pain |

.406** | .573** | .320** | .442** | .259** | .651** | .657** | .713** | .237* | −.017 | .551** | .182** | .176** | .141** | .341** | −.004 | .077 | 1 | |||||

| Sex with vaginal penetration, negative thoughts secondary to pain |

.329** | .567** | .335* | .403** | .276** | .701** | .751** | .789** | .266** | −.032 | .583* | .199** | .151** | .152** | .354** | −.015 | .091 | .820** | 1 | ||||

| Sex, burning with urination |

.549** | .473** | .383** | .644** | .275** | .497** | .516** | .447** | .310** | −.047 | .449** | .165** | .069 | .157** | .189** | .095 | .085 | .476** | .482** | 1 | |||

| Pregnancy, worry | −.017 | −.032 | .025 | −.052 | −.021 | −.068 | −.092 | −.092 | 0 | .060 | −.109 | −.083 | −.034 | −.141** | −.056 | −.105 | −.081 | −.061 | −.086 | −.030 | 1 | ||

| Sex life, happy with |

.133* | .218** | .186** | .231** | .086 | .327** | .346** | .347** | −.051 | −.054 | .342** | .384** | .235** | .333** | .499** | .186** | .205** | .281** | .326** | .306** | −.094 | 1 | |

| Partner, talk with, about sex |

.025 | .124* | .052 | .045 | .024 | .227** | .159** | .125* | −.205** | .082 | .110 | .318** | .142* | .305** | .330** | .124** | .141* | .152** | .164** | .156** | −.096 | .606** | 1 |

p < 05.

p < 01.

Cronbach’s standardized alpha was used to determine internal consistency within each of the item domains (urologic, genital, and sexual) as well as the entire instrument. Internal consistency reliability was .772 for the urological domain, .739 for the 12-item genital domain, .874 for the sexual domain, and .867 for the entire urogenital questionnaire (Table 5).

Table 5.

Internal Consistency Measures Using Cronbach’s Standardized α

| Subscale | Number of Items |

Cronbach’s α |

Item Mean |

Mean Scale |

SD | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urologic | 10 | .772 | 1.53 | 15.29 | 3.378 | 0.77 |

| Genital | 12 | .739 | 1.25 | 15.96 | 2.655 | 0.69 |

| Sexual | 23 | .874 | 2.17 | 49.96 | 8.920 | 1.12 |

| Entire instrument |

45 | .867 | 1.78 | 79.85 | 11.000 | 1.46 |

Validity measures and factor analyses

Exploratory factor analysis was used to explore the underlying dimensions and factors of the construct of urogenital atrophy and their congruence with the theory of unpleasant symptoms (Munro, 2005; Pett, Lackey, & Sullivan, 2003). The Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (KMO) was calculated at .772 and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < .000, which indicated moderate to high relatedness of the items. The factor structure of the 45-item urogenital questionnaire was subsequently examined using a principal components analysis with Varimax rotation. Three factors (urologic, genital, and sexual) with eigenvalues >1.0 emerged, which explained 93% of the variance. This was an expected outcome; therefore, a second factor analysis was conducted in the same manner to explore factors within these domains (urologic, genital, and sexual). The factor analysis yielded eleven factors with eigenvalues >1.0, which explained 63.46% of the variance.

Of interest, the second factor analysis allowed only 280 participants, because 136 (37.4%) participants had responded no sexual activity to many of the sexuality items, thus eliminating their inclusion. Several questions emerged from the researchers: Would items be retained that required the practice of penile vaginal intercourse with a heterosexual partner? Would items remain unanswered if based on sexual activity? If so, the instrument was not appropriate for all women.

The factor analysis (Table 6) was performed again using a principal components analysis with Varimax rotation on the instrument without items that were directly linked to sexual action(s) versus the sexual domain. Items that addressed sexual desire, interest, partner communication, and negative feelings of vaginal/genital sexual activity were retained. The KMO was calculated at .774; the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at .000, indicating moderate to high relatedness of the items. Nine factors with eigenvalues >1.0 explained 63.78% of the variance (Table 6). When the items based strictly on sexual function were removed, 348/364 of women were included in the factor analysis as compared to 280 women.

Table 6.

Principal Components Analysis of Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire, Excluding Sexual Action/Activity Items (n = 348/364)

| Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

Factor 5 |

Factor 6 |

Factor 7 |

Factor 8 |

Factor 9 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Urinary Incontinence |

Pain With Sexual Activity |

Genital Itching/ Odor |

Burning With Urination |

Genital Irritation |

Sexual Desire/ Interest |

Partner Communication |

Change Urinary Patterns |

Vaginal Discharge |

| Incontinence, urge | .802 | ||||||||

| Incontinence, with cough, sneeze, or laugh |

.773 | ||||||||

| Incontinence, embarrassment |

.732 | ||||||||

| Urinary urgency | .713 | ||||||||

| Incontinence, no reason | .700 | ||||||||

| Thought of sexual activity worrisome, causes pain in vagina |

.888 | ||||||||

| Thought of sexual activity worrisome, might cause genital pain |

.880 | ||||||||

| Vagina, dry | .728 | ||||||||

| Thought of sexual activity bothers me, external genitals are tender |

.656 | ||||||||

| Vagina, itching | .766 | ||||||||

| Vagina, odor | .731 | ||||||||

| External genital, odor | .713 | ||||||||

| External genital, itching | .677 | ||||||||

| Urethral burning after urination |

.866 | ||||||||

| Burning after urination | .755 | ||||||||

| External genital, swollen | .324 | .347 | .342 | ||||||

| Irritation from toilet tissue | .781 | ||||||||

| External genital, tenderness | .681 | ||||||||

| Irritation from clothing | .521 | .565 | |||||||

| Interest in sexual activity | .933 | ||||||||

| Desire for sexual activity | .924 | ||||||||

| Talk with partner about sex | .864 | ||||||||

| Happy with sex life | .813 | ||||||||

| Incomplete emptying | .727 | ||||||||

| Daytime urinary frequency | .660 | ||||||||

| Nocturnal urination | .536 | ||||||||

| Vagina, wh ite/creamy discharge |

.717 | ||||||||

| Pregnancy, worry | .702 | ||||||||

| Vagina, yellowish-green discharge |

.314 | .520 | |||||||

| Vagina, bleeding other than menstruation |

(.867) | ||||||||

| Eigenvalue (E) | 3.72 | 3.15 | 3.21 | 2.49 | 2.37 | 1.86 | 1.68 | 2.24 | |

| Cronbach’s coefficient α | .807 | .815 | .773 | .740 | .687 | .917 | .751 | .525 | .439 |

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity (Table 7) was established by correlating the new instrument to existing reliable and valid instruments that measured similar constructs. Genital symptoms from the Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire correlated with the Endocrine scale (ES) of the FACT-B (r = .549), emotional items with the FACT-B (r = .248), and sexuality items with the FSFI (r = .188). All correlations were statistically significant (p < .01).

Table 7.

Concurrent Validity: Pearson Correlations Comparing Items From Urogenital Atrophy Instrument to Existing Valid Instruments

| Items on FACT-B, ES | Vaginal Discharge |

Vaginal Itching/ Irritation |

Vaginal Bleeding/ Spotting |

Vaginal Dryness |

Sex, Pain/ Discomfort |

Sex, Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal bleeding | .444** | |||||

| Sex, bleeding after penetration | .200** | |||||

| Vaginal dryness | .790* | |||||

| Vaginal itching | .580** | |||||

| Vaginal discharge, creamy | .521** | |||||

| Vaginal discharge, yellowish-green | .446** | |||||

| Vagina, pain with sex | .672** | |||||

| Vagina, pain with penetration | .794** | |||||

| Vagina, intolerance of penetration/pain | .682** | |||||

| Desire sexual activity | .537** | |||||

| Interest in sexual activity | .518** | |||||

| Sex with penetration, pain | .668** | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Items FACT-B, ES | Partner, Close | Sex Life, Satisfaction |

Family, Emotional Support |

|||

|

| ||||||

| Desire sexual activity | .366** | |||||

| Interest sexual activity | .352** | |||||

| Happy sex life | .503** | .807** | .259** | |||

| Talk with partner, sex life | .536** | .263** | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Instruments | FACT-B, ES | ES Subscale | FSFI | |||

|

| ||||||

| Urogenital atrophy | .248** | .549** | .188* | |||

Note: FACT-B, ES = Functional Assessment of Chronic Therapy, Breast, Endocrine Scale.

Divergent validity

Divergent validity (Table 8), as measured by the correlation between two presumably unrelated constructs (Munro, 2005), was established by correlating 10 urinary function items from the urogenital atrophy questionnaire to eight items from the FSFI, a measure of sexual dysfunction. Using Pearson product-moment correlation r, the items did not correlate with each other (.210 > r > .000). These differences validated the ability of the urinary domain of the urogenital atrophy questionnaire to discriminate between urinary and sexual items, thus reflecting two different and unrelated constructs and instruments.

Table 8.

Divergent Validity: Pearson Correlations Between Items From the Urinary Domain of the Urogenital Atrophy Instrument

| Items FSFI | Burning After Urination |

Urethral Burning Urination |

Incontinence, With Sneeze or Cough |

Incontinence, No Reason |

Incontinence, Embarrassment |

Incontinence, Urge |

Leakage, Urine |

Nocturnal Urination |

Incomplete Emptying |

Daytime Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, desire | .570 | .101 | .092 | .149 | .069 | .143 | .184 | .065 | .046 | .100 |

| Sex, arousal | .073 | .060 | .139 | .179 | .042 | .124 | .205 | .013 | .082 | .133 |

| Lubrication, intercourse |

.090 | .082 | .121 | .130 | .071 | .154 | .210 | .063 | .063 | .131 |

| Orgasm, frequency |

.063 | .047 | .104 | .128 | .025 | .119 | .177 | .050 | .074 | .142 |

| Satisfaction, partner |

.103 | .066 | .058 | .083 | .113 | .022 | .088 | .009 | .075 | .027 |

| Satisfaction, sex life |

.105 | .060 | .085 | .061 | .087 | .040 | .071 | .020 | .064 | .090 |

| Pain with penetration |

.144 | .111 | .037 | .045 | .030 | .017 | .054 | .065 | .041 | .000 |

| Pain after intercourse |

.205 | .161 | .008 | .012 | .009 | .022 | .032 | .032 | .029 | .025 |

Note: FSFI = Female Sexual Function Index.

Discussion

This study resulted in a reliable and valid self-report instrument to describe symptoms related to urogenital atrophy, the Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire (UAQ). Using the TOUS and data generated from an extensive literature review, the three domains of urogenital atrophy (e.g., urologic, genital, and sexual) and related self-reported symptoms were defined and categorized. The item pool was generated from these sources with input from symptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer survivors and experts. Face and content validity were established. The pilot study (n = 30) indicated high temporal stability of the urogenital atrophy questionnaire, as evidenced in the 1-month test–retest analysis. This reliability measure supported the ability of the urogenital atrophy instrument to measure the chronic symptoms of urogenital atrophy from urinary, genital, and sexual domains. Reliability estimates ≥.70 are acceptable for a new instrument (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994); high interitem correlations were observed of the three domain scales and this first-time urogenital atrophy questionnaire.

This psychometric study enabled a survey of a heterogenous sample of women with, and without, breast cancer. Women, especially breast cancer survivors, were eager to help with the study, verbalizing their concern and frustration with the unpleasant symptoms they experienced. The sample included women of various age groups, menopausal status, educational status, and income levels. It is interesting to note that 42.9% of breast cancer survivors were postmenopausal, as compared to only 27.5% of age-matched women without breast cancer. A limitation of the sample is the paucity of ethnic variations, as 88.2% of the sample identified themselves as non-Hispanic and Caucasian, reflective of this Midwestern facility.

Factor analysis of the urogenital questionnaire supported the urologic, genital, and sexual domains. Removal of the items related to current sexual activity revealed a factor structure that closely matched that of the full instrument, which allowed statistical analysis of nearly all participants’ responses, whether sexually active or not. A factor structure emerged that can address all women and their full range of experiences. Thirty items were retained that demonstrated use for women of all ages (23-89 years of age), independent of sexual orientation, partner status, and/or practice of penile vaginal intercourse. These findings will allow women to report symptoms using the urogenital atrophy instrument regardless of type, frequency, and level of sexual activity.

The urogenital atrophy instrument is unique in regard to the number and type of items included from the urologic, genital, and sexual domains. The instrument centers on the physical and psychological dimensions of urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors and enables subjective reporting of symptoms. The instrument reflects the urogenital side effects experienced by breast cancer survivors and facets of the menopause experience. Women, regardless of their level of sexual activity, partner status, or sexual orientation can report symptoms that may alter sexual activity, and/or provide enjoyment, including self-stimulation.

As previously discussed, various questionnaires have been utilized in studies to document the symptoms of urogenital atrophy. Several of these instruments lacked sound psychometric properties and/or inclusion of common urinary, genital, and/or sexual symptoms. Most of these instruments address a wide array of menopausal issues, allowing only two to four items for urogenital symptoms. Often, items that assess sexuality assume a current, heterosexual partner with the practice of penile vaginal intercourse, inquiring about “pain with intercourse.” In the current study, 37.5% of breast cancer survivors reported no current practice of penile vaginal intercourse; 26.2% no current sexual activity; 1.9% had a female partner, 6.3% reported “self” as a partner, 26.2% reported no partner, and 70.6% reported a male partner. The urogenital atrophy questionnaire must be broad enough to enable all women to self-report symptoms. When additional information is sought about the specific activities related to sexual functioning, instruments such as the FSFI or FSAQ could be utilized.

Although the study obtained a representative sample of women respective to age, the sample was limited in regard to ethnic variations, lower educational preparation, and lower income levels (Table 1). It remains unknown if these factors are directly related to the occurrence or severity of urogenital atrophy; examinations of a more diverse sample would be beneficial.

The tested instrument (45 items) is lengthy and repetitive for use in the clinical and/or research arenas. Future research goals include refinement of the questionnaire to make this instrument as brief as possible, yet as comprehensive as necessary to evaluate symptoms and interventions. This questionnaire could be added to other measures of menopausal symptoms to provide a more comprehensive profile of symptoms related to urogenital atrophy.

A rapid scoring method needs to be developed to cue providers of the need for additional assessment of signs and symptoms. A rapid scoring system would also enhance evaluation of interventions, whether in the clinical setting or for evaluation within a clinical trial. This self-report urogenital atrophy questionnaire would be further strengthened with the addition of a concomitant objective marker.

This study was successful in designing a reliable and valid instrument that describes subjective urogenital symptoms in breast cancer survivors regardless of their level of sexual activity, partner status, or sexual orientation. Additional item reduction will eliminate redundant items and provide a psychometrically sound, brief, and concise instrument. The Urogenital Atrophy Questionnaire could replace or augment instruments that have not been psychometrically tested at the item and/or factor levels. The unpleasant symptoms of urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors, as well as women without breast cancer are prevalent and should be routinely evaluated.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their appreciation to Christopher Holloman, PhD, Director of Statistical Consulting Service; Maggie Lynch Lester, DPT, Data Manager; staff members at JamesCare in Dublin and at Comprehensive Breast Health Center, the Ohio State University.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: (1) Oncology Nursing Society Doctoral Scholarship, (2) National Institutes of Health Fellowship Grant 1 T32 RR 023260-01, and (3) National Institutes of Health, National Center of Research Resources, General Clinical Research Center Grant M01-R00034.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, Reeve BB, Bowen DJ, Baumgartner KB, McTiernan A. Psychometric properties of a tool for measuring hormone-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors. PsychoOncology. 2006;15:985–1000. doi: 10.1002/pon.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins L, Fallowfield LJ. Fallowfield’s Sexual Activity Questionnaire in women with, without and at risk of cancer. Menopause International. 2007;13:103–109. doi: 10.1258/175404507781605578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:3322–3330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barni S, Mondin R. Sexual dysfunction in treated breast cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 1997;8:1–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1008298615272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekhout AH, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Symptoms and treatment in cancer therapy-induced early menopause. Oncologist. 2006;11:641–654. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-6-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broeckel JA, Thors CL, Jacobsen PB, Small M, Cox CE. Sexual functioning in long-term breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2002;75:241–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1019953027596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Fallowfield LJ. Recognition and management of treatment-related side effects for breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant endocrine therapy. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2008;107:167–180. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde DM, Pinto-Neto AM, Cabello C, Sa DS, Costa-Paiva L, Martinez ED. Menopause symptoms and quality of life in women aged 45-65 years with and without breast cancer. Menopause. 2005;12:436–443. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000151655.10243.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne K, Revicki D, Hunt T, Corey R, Stewart W, Bentkover J, Abrams P. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire: The OAB-q. Quality of Life Research. 2002;11:563–574. doi: 10.1023/a:1016370925601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daker-White G. Reliable and valid self-report outcome measures in sexual (dys)function: A systematic review. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2002;31:197–209. doi: 10.1023/a:1014743304566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson SB, Grant MM. Assessing vaginitis. In: Frank-Stromberg M, Olsen SJ, editors. Instruments for clinical health-care research. 3rd ed. Jones and Bartlett; Sudbury, MA: 2004. pp. 663–682. [Google Scholar]

- DeRogatis LR. Assessment of sexual function/dysfunction via patient reported outcomes. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2008;20:35–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield LJ, Leaity SK, Howell A, Benson S, Cella D. Assessment of quality of life in women undergoing hormonal therapy for breast cancer: Validation of an endocrine symptom subscale from FACT-B. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1999;55:189–199. doi: 10.1023/a:1006263818115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:2371–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, Davidson S. Effects of perineal care on diabetic vulvovaginitis: Final report of project. Division of Nursing, Bureau of Health Manpower, Health Resources Administration, Department of Health and Human Resources; Washington, DC: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Sturdee DW, Palin SL, Majumder K, Fear R, Marshall T, Paterson I. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: The prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric. 2006;9:49–58. doi: 10.1080/13697130500487224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C, Ramnarace T, McCaffrey R. Sexuality and intimacy issues facing women with breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33:1163–1167. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.1163-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics 2010. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley C. Estrogen and its effect on vaginal atrophy in post-menopausal women. Urologic Nursing. 2007;27:40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkova J, Davis MP, Walsh D, Tiernan E, O’Leary N, LeGrand SB, Russell KM. Cancer symptom assessment instruments: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:1459–1473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz ER, Pugh LC. The theory of unpleasant symptoms. In: Smith MJ, Liehr P, editors. Middle range theory for nursing. Springer; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lester J, Bernhard L. Urogenital atrophy in breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2009;36:693–698. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.693-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester JL. Development of a self-report instrument for use in the clinical setting that describes symptoms related to urogenital atrophy in women with breast cancer (Unpublished dissertation) The Ohio State University; Columbus: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe NK, Ryan-Wenger NA. A clinical test of women’s self-diagnosis of genitourinary infections. Clinical Nursing Research. 2000;9:144–160. doi: 10.1177/105477380000900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research. 1986;35:382–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna SP, Whalley D, Renck-Hooper U, Carlin S, Doward LC. The development of quality of life instrument for use with postmenopausal women with urogenital atrophy in the UK and Sweden. Quality of Life Research. 1999;8:393–339. doi: 10.1023/a:1008884703919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. 5th ed. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric testing. 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pett MA, Lackey NR, Sullivan JJ. Making sense of factor analysis: The use of factor analysis for instrument development in health care research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Agostino R., Jr. The female sexual function index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer J, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, Blacker C, Kresge CL, Decker V, Decker DA. Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast Journal. 2005;11:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA. The BCPT Symptom Scales: A measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with or at risk for breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:448–456. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willhite LA, O’Connell MB. Urogenital atrophy: Prevention and treatment. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:464–480. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.5.464.34486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibecchi L, Greendale GA, Ganz PA. Comprehensive menopausal assessment: An approach to managing vasomotor and urogenital symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2003;30:393–407. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.393-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]