Cancer is not a modern illness. Cancer care, however, has only recently been recognized as a major worldwide challenge given the financial, social, and economical strain of disease that indubitably follows. The prevalence of cancer, primarily a disease of the aged, is rising as a consequence of longer expected life spans seen all over the world. The old perception of cancer being a disease of the affluent is far and stretched from the dismal reality, with almost two-thirds of the 8 million annual cancer deaths worldwide occurring in low- or middle-income countries. In addition, it is postulated that by 2030, 70% of all reported cancer cases will originate from the similar region.[1,2]

Pakistan sits at the center of the geographical developing world, and is a typical example of a country with great cancer morbidity secondary to limited health resources.[3] Seventy percent of the population resides in the rural outskirts, and disparities in infrastructure both discourage and hinder most people from seeking medical attention leaving them at the mercy of their disease. An unsuccessful formula prevails, with ill-supported efforts on one end, and poor community proactivity on the other. This leaves Pakistanis with little or no knowledge of cancer screening, detection, and diagnosis, let alone the testing journey through treatment. Patients who do manage to seek care are usually beyond cure, adding to the nationwide burden of management of chronic disease.

This burden is particularly highlighted when the improved survival rates in high-income countries are benchmarked against lower survival rates in low-income countries. Case fatality from cancer (approximated by the ratio of incidence to mortality in a specific year) is approximately 46% in high-income countries, compared with 75% in low-income countries.[3]

The idea behind effectively combating the staggering cancer cases is not a new one – broad partnerships amongst research institutions, international organizations, nongovernmental organizations, the national government, and pharmaceutical industries on both a local and international level provide an excellent prototype to a successful campaign, and a working model already exists in the West. Unfortunately, as is the case with most health concerns, these programs have not received enough priority by the national government. It is only with their support and contribution that schemes can be perfectly tailored to the local population and executed.

Cancer control begins at understanding the relationship between demographics and disease. Surveillance programs and registries are necessary to collect, analyze, and interpret this data specifically to cancer. This would provide the basic essentials to understanding the disease process, including incidence, prevalence, trends, mortality, and survival. A realistic plan based on these statistics would follow, which would not only be cost effective, but sustainable.

The initial data would also evaluate the impact of prevention; early detection/screening, treatment and palliative care programs. Up to one-third of cancers in the developing world are curable if recognized early – relevant physical examination for oral cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing for cervical cancer to name a few, are simple and predictable screening tests for vulnerable populations.[4,5]

On the other end of the disease progression spectrum lies palliative care, which plays a major role in the continuum of cancer therapy. Palliative medicine has been reserved as a topic for specialists and intensive care nurses. Introducing the theme into training at all levels can enhance the pain-relieving options a physician can provide. The lack of well-informed health care professionals currently in Pakistan remains the major ironic obstacle in patients receiving analgesia, particularly morphine. Pain and symptom control, coupled with the correct counseling allow patients to die with dignity and families to accept the event.[6]

The ideas addressed here are neither novel nor intangible. The root of the problem is two-fold. Developing countries, as a whole, tend to resist multi-international efforts, and are not keen on investing in the health sector. Once this is tackled can the focus of resources be shifted from the West to developing countries, where the vast majority of burden actually lies.[7]

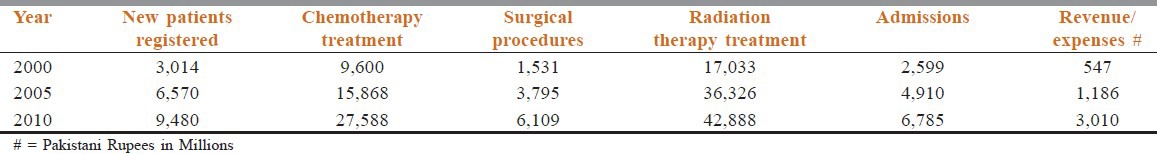

Addressing these challenging inequities entails numerous partnerships and in turn, their partnership with the worldwide community. Given the diverse populations and diverse health care infrastructures that currently exist, research directed toward optimizing treatment, symptom relief, prevention, early detection, and resource distribution is imperative. The Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center is a classical example of how good intentions, technical knowhow, and community resources can come together to create wonders.Table 1 shows how facilities provided by this center have benefited increasing number of cancer patients in a cost effective manner.[8] In fact 75% of all patients treated by us get financial assistance.

Table 1.

Statistics from Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center, Lahore, Pakistan (established 1994)

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Boyle P, Levin B, editors. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. WHO World Cancer Report 2008; p. 510. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 12]. GLOBOCAN 2008 v. 1.2. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noronha V, Tsomo U, Jamshed A, Jai MA, Wattegama S, Baral RP, et al. A fresh look at oncology facnts on south central Asia and SAARC countries. S Asian J Cancer. 2012;1:1–4. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.96489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thomas G, Muwonge R, Thara S, Mathew B, et al. Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1927–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66658-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1385–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parikh PM, Narayanan P, Bhattacharyya GS. Optimizing patient outcome: Of equal importance in the palliative setting. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49:258–61. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.104481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breakaway: The global burden of cancer–challenges and opportunities. A Report from the Economist Intelligence Unit. 2009. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www.livestrong.org/pdfs/GlobalEconomicImpact .

- 8. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www.shaukatkhanum.org.pk/about-us/statistics-gg/patient-statistics.html .