Sir,

There is evidence of possible association between Hepatitis C virus and lung cancer.[1,2] We present a case to emphasize on this association.

A 29-year-old, non smoker was admitted with the chief complaints of chest pain and breathlessness for 2 months and hemoptysis for 1 month. He was a never smoker and didn’t have significant exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke. He had no family history of lung cancer, but had received 3 units of blood transfusions 9 years back. Routine investigations except for liver function tests were within normal limits. His serum bilirubin was 3 mg/dl, SGOT 65 U/L, SGPT 52 U/L and alkaline phosphatase 240 U/L. Anti HCV antibodies were detected through ELISA method. His HCV genotype was type 1. HCV quantitative report was 21, 90,000 IU/ml HCV RNA. He tested negative by ELISA for HIV, Ig M Anti-HAV, Ig G Anti- HAV and HBsAg. Sputum for AFB smear was negative and PPD showed induration of 3 mm after 72 h.

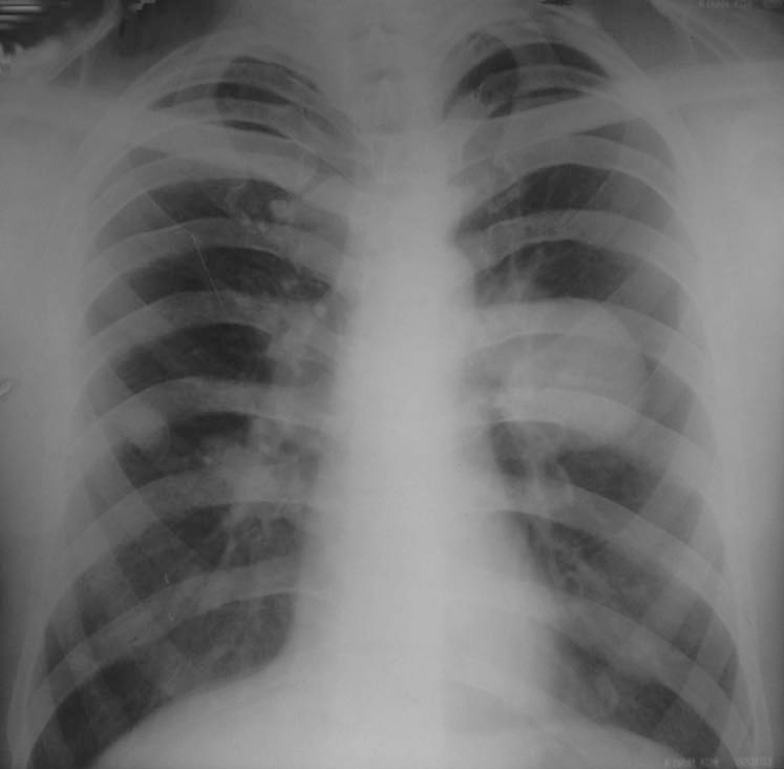

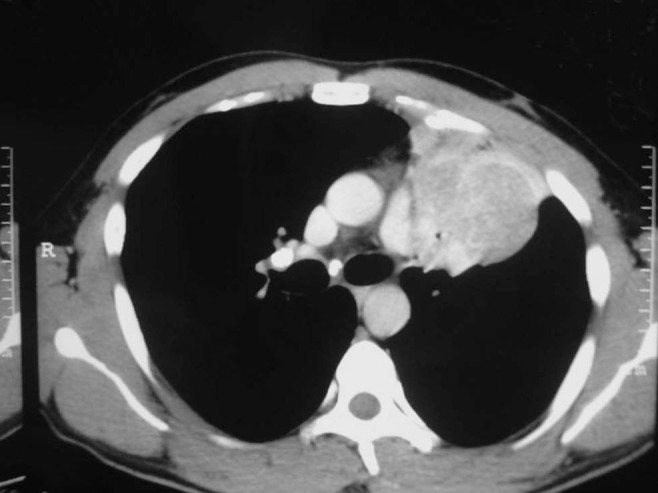

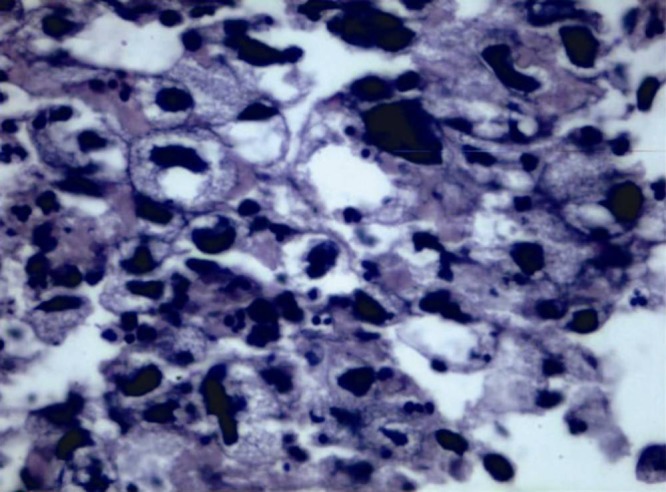

Chest X ray PA showed a mass lesion in the left middle zone [Figure 1]. Contrast enhanced CT scan (CECT) of thorax revealed a heterogeneously enhancing mass lesion with enhancement of 68 Hounsfield Units in the left upper lobe, abutting the chest wall [Figure 2]. CT-guided biopsy of lung mass and histopathology revealed an adenocarcinoma [Figure 3]. Immunohistochemistry revealed tumor positive for TTF-1. CECT of neck and abdomen were negative, thus ruling out a primary from these regions. The diagnosis of adenocarcinoma lung with Hepatitis C seropositivity was made.

Figure 1.

A Chest X Ray PA view showing a mass lesion in the left middle zone

Figure 2.

A CECT Thorax showing left collapse with a mass lesion in the anterior segment of left upper lobe

Figure 3.

A high power micrograph of a section through the lung mass showing cancer cells with abnormally large nuclei

Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, occupational exposure (arsenic, asbestos, chromates, chloromethyl ethers, nickel, radon), combustion-generated carcinogens, fumes and smoke from cooking stoves and high-fat diet are risk factors for lung cancer in never smokers.[3] It is a well-known fact that viruses cause lung cancer in never smokers. Human Papilloma virus, Simian virus 40 and Epstein Barr viruses have also been implicated in causation of lung cancer.[4,5,6]

These viruses cause lung cancer by multiple and complex mechanisms. Human Papilloma virus expresses viral oncoproteins E6/E7 and E5.[4] Oncoprotein E7 hypermethylates and inactivate regions of P16 genes leading to uncontrolled mitosis.[4] This mechanism confers resistance to Cisplatin in HPV subtype 16/18 infected lung cancer. Oncoprotein E5 phosphorylates pRB gene leading to uncontrolled cell replication and inhibiting the tumor suppressor gene p21 leading to cancer relapse.[4] Simian Virus 40 DNA sequences are found in pleural mesotheliomas.[7] Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) association has been found in two types of lung cancers, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Lymphoepithelioma-like cancer of the lung tends to affect young never-smoker patients.[8]

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is endemic worldwide and affects 170 million people comprising 3% of the world population. The chronic inflammation caused by Hepatitis C infection is responsible for carcinogenesis.[9] Since Hepatitis C virus is an emerging infection in India, its contribution to the “epidemic” of lung cancer will have long-term public health implications in the coming decades.

We draw attention to the need for multicenter studies on Indian patients with HCV infection to clarify its association with lung cancer.

References

- 1.Arslan S, Ta N, Akkurt I. Status of hepatitis C virus infection in lung cancer patients. Basic Clin Sci. 2010;1:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uzun K, Alıcı S, Ozbay B, Gencer M, Irmak H. The incidence of hepatitis C virus in patients with lung cancer. Turkish Respiratory J. 2002;3:91–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreuzer M, Kreienbrock L, Gerken M, Heinrich J, Bruske-Hohlfeld I, Muller K, et al. Risk factors for lung cancer in young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:1028–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng YW, Chiou HL, Sheu GT, Hsieh LL, Chen JT, Chen CY, et al. The association of human papillomavirus 16/18 infection with lung cancer among nonsmoking Taiwanese women. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2799–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Testa JR, Carbone M, Hirvonen A, Khalili K, Krynska B, Linnainmaa K, et al. A multi-institutional study confirms the presence and expression of simian virus 40 in human malignant mesotheliomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4505–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massion PP, Carbone DP. The molecular basis of lung cancer: Molecular abnormalities and therapeutic implications. Respir Res. 2003;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strickler HD, Goedert JJ, Devesa SS, Lahey J, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Rosenberg PS. Trends in U.S. pleural mesothelioma incidence rates following simian virus 40 contamination of early poliovirus vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:38–45. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho JC, Lam WK, Wong MP, Wong MK, Ooi GC, Ip MS, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung: Experience with ten cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8:890–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trichopoulos D, Psaltopoulou T, Orfanos P, Trichopoulou A, Boffetta P. Plasma C-reactive protein and risk of cancer: A prospective study from Greece. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:381–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]