Abstract

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangements are present in a small subset of non-small-cell lung cancers. ALK-positivity confers sensitivity to small-molecule ALK kinase inhibitors, such as crizotinib. The integration of crizotinib into standard treatment practice in NSCLC will rest on the widespread implementation of an effective screening system for newly diagnosed patients with NSCLC which is flexible enough to incorporate new targets as treatments are developed for them. Phase I and II studies of crizotinib in ALK-positive lung cancer have demonstrated significant activity and impressive clinical benefit, which led to its early approval by USFDA in 2011. Although crizotinib induces remissions and extends the lives of patients, there have been reports of emerging resistance to Crizotinib therapy. In this review, we discuss the history, mechanism of action, uses, adverse effects, dose modifications and future challenges and opportunities for patients with ALK-positive lung cancers.

Keywords: ALK mutation, ALK inhibitors, ALK positive Non-small cell lung cancer, Crizotinib

Introduction

Management for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has historically consisted of systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy. An improved understanding of the molecular pathways that drive malignancy in NSCLC, as well as other neoplasms, has led to the development of agents that target specific molecular pathways in malignant cells. These agents are expected to preferentially kill malignant cells, but be relatively innocuous to normal cells. Many established targeted therapies are administered as orally-available small molecule kinase inhibitors, but targeted therapy can also be administered intravenously in the form of monoclonal antibodies or small molecules.

The echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4)–anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is a fusion-type protein tyrosine kinase found in 4 to 5% of NSCLC.[1,2,3] The ALK gene arrangements are largely mutually exclusive with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or Kirsten-ras (KRAS) mutations.[4] Screening for this fusion gene in NSCLC is important, as ALK-positive tumors are highly sensitive to therapy with ALK-targeted inhibitors.

Molecular pathogenesis

The EML4-ALK fusion oncogene is the result of an inversion in the short arm of chromosome 2 (Inv (2)(p21p23)) that juxtaposes the 5’ end of the EML4 gene with the 3’ end of the ALK gene, joining exons 1-13 of EML4 to exons 20-29 of ALK, resulting in the novel fusion oncogene EML4-ALK.[1,5] The resulting chimeric protein, EML4-ALK, contains an N-terminus derived from EML4 and a C-terminus containing the entire intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of ALK, which mediates the ligand-independent dimerization and/or oligomerization of ALK, resulting in constitutive kinase activity. Multiple variants of EML-ALK have been reported, which encode the same cytoplasmic portion of ALK, but EML4 is truncated at different points.[6,7,8,9,10] Crizotinib also inhibits the c-Met/Hepatocyte growth factor receptor (HGFR) tyrosine kinase, which is involved in the oncogenesis of a number of other histological forms of malignant neoplasms.[11]

The oncogenic role of the ALK fusion oncogene provides a potential avenue for therapeutic intervention. Cancer cell lines harboring the EML4-ALK translocation are effectively inhibited by small molecule inhibitors that target the ALK tyrosine kinase.[8] In vivo, treatment of EML4-ALK transgenic mice with ALK inhibitors results in tumor regression,[12] supporting the notion that ALK-driven lung cancers are highly dependent on the fusion oncogene.

The overall incidence of ALK gene rearrangements has been about 4%.[1,6,8,9,10,13] In the Japanese, the incidence of ALK positivity is noted to be around 6.7%, as reported by Dr. Mano and colleagues.[2] Sun et al. have reported the incidence of EML-4-ALK to be 5.8% in East Asians.[14] There has been no published data on EML-ALK incidence from India. In our center, the incidence is 2.7% (one year data). Five cases have been positive so far out of 187 (unpublished observation).

Chemistry

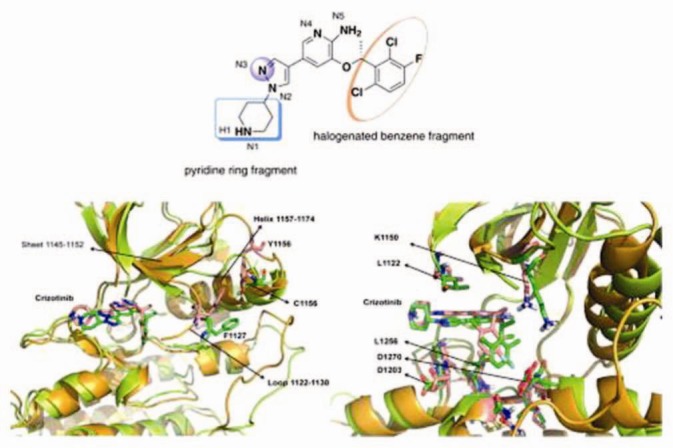

Crizotinib is an oral receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. The molecular formula for crizotinib is C21H22Cl2FN5O. The molecular weight is 450.34 Daltons.[15,16] Crizotinib is described chemically as (R)-3-[l-(2,6-Dichloro-3-fluorophenyl) ethoxy]-5-[1-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl] pyridin-2-amine [Figure 1]. Crizotinib is a white- to pale-yellow powder with a pKa of 9.4 (piperidinium cation) and 5.6 (pyridinium cation). The solubility of crizotinib in aqueous media decreases over the range of pH 1.6 to pH 8.2 from greater than 10 mg/mL to less than 0.1 mg/mL. The log of the distribution coefficient (octanol/water) at pH 7.4 is 1.65.[15,16]

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the structure of Crizotinib. Represented with permission and license from Elsevier Limited

Mechanism of action

Crizotinib is an inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinases including ALK, Hepatocyte Growth Factor Receptor (HGFR, c-Met), and Recepteur d’Origine Nantais (RON). Translocations can affect the ALK gene resulting in the expression of oncogenic fusion proteins. The formation of ALK fusion proteins results in the activation and dysregulation of the gene's expression and signaling, which can contribute to increased cell proliferation and survival in tumors expressing these proteins. Crizotinib demonstrates concentration-dependent inhibition of ALK and c-Met phosphorylation in cell-based assays using tumor cell lines, and also demonstrates antitumor activity in mice bearing tumor xenografts that express EML4- or NPM-ALK fusion proteins or c-Met.[15,16] Crizotinib is a multitargeted small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which had been originally developed as an inhibitor of the mesenchymal epithelial transition growth factor (c-MET); it is also a potent inhibitor of ALK phosphorylation and signal transduction. This inhibition is associated with G1-S phase cell cycle arrest and induction of apoptosis in positive cells in vitro and in vivo. Crizotinib also inhibits the related ROS1 receptor tyrosine kinase.

Detection of EML4-ALK Mutation

The ALK gene rearrangements can be detected in tumor specimens using immunohistochemistry (IHC), reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of the cDNA, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).[17,18,19,20,21,22]

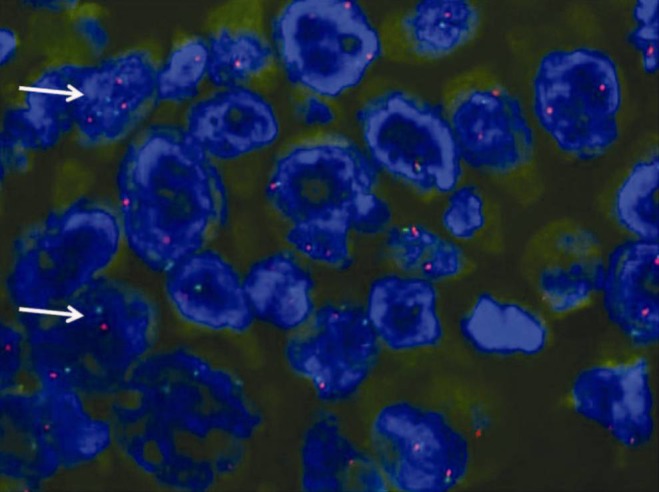

Fluorescence in situ hybridization is the gold standard for diagnosing ALK-positive NSCLC. The commercial break-apart probes include two differently colored (red and green) probes that flank the highly conserved translocation breakpoint within the ALK. In non-rearranged cells, the overlying red and green probes result in a yellow (fused) signal; in an ALK rearrangement, these probes are separated and splitting of the red and green signals is observed [Figure 2]. There are atypical patterns of rearrangement that also respond to crizotinib.[17,18,19,20,21,22]

Figure 2.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization showing split red and green signals that flank the ALK translocation site in a tissue specimen showing EML4-ALK positive mutation as shown by white arrows

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and RT PCR have been used to detect ALK mutation, but there is some technical difficulty at present, and hence, it is not considered as the standard.

History

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase was first identified as a potential drug target in cancer 15 years earlier, when it was discovered as a fusion kinase with nucleophosmin in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. ALK was first recognized as a molecular target in NSCLC only in 2007, when Dr. Mano and colleagues reported that 6.7% of Japanese patients with NSCLC harbor a fusion of EML4 with the intracellular kinase domain of ALK. Based on in vitro studies with an ALK inhibitor WHI-P154 and a Ba/F3 cell line model, Dr. Mano's team suggested that ALK might represent a therapeutic target in patients with ALK-positive NSCLC.[1,2]

One year prior to Dr. Mano's discovery, PF-02341066, now known as crizotinib, a small molecule inhibitor of ALK had just entered clinical trials. It had been developed to target c-MET, but was also known to inhibit ALK. In order to test ALK rearrangement-a potential target in NSCLC which confers sensitivity to crizotinib a diagnostic assay was needed. This assay was developed by Dr. John Lafrate, at Massachusetts General Hospital, using commercially available ALK FISH probes. With this assay, investigators proceeded to screen NSCLC tumors, leading to the identification of both the key clinicopathological features associated with ALK rearrangement and screening of clinically enriched populations based on these results. The first patient with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC was treated with crizotinib at the end of December 2007, just four months after the pivotal Nature publication. This patient experienced an almost immediate improvement in his disease-related symptoms, leading to large-scale screening efforts and recruitment of additional ALK-positive patients at phase 1 study sites around the world.

Overview of Clinical Trials

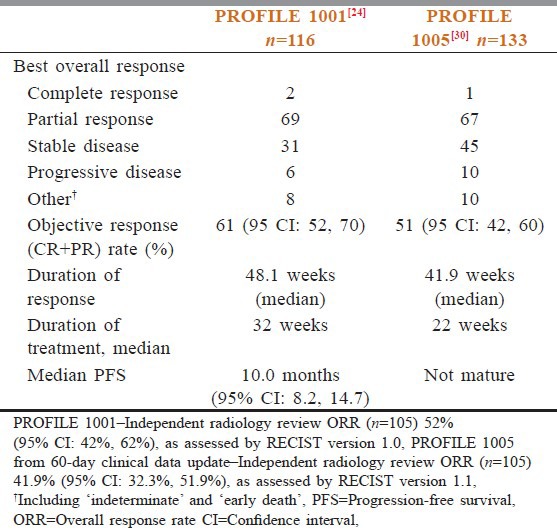

The antitumor efficacy of crizotinib was initially demonstrated in two multicenter, single-arm studies.[23,24] Dosage for these extended series was 250 mg, orally, given twice a day, based on results from the initial phase I dose escalation study. In aggregate, these studies included 255 patients, all of whose tumors contained an ALK gene rearrangement, as shown by FISH. Overall, 95% of the patients had metastatic disease and 5% had locally advanced NSCLC. Overall, 94% of the patients had received prior systemic therapy for advanced or metastatic disease, and 76% had received two or more treatment regimens. The combined objective (complete plus partial) response rate was 55%, the majority of which was achieved during the first eight weeks of treatment. The median durations of response at the time of analysis of the two studies were 42 and 48 weeks, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of results of profile 1001 and profile 1005 trials

Evidence of the impact of crizotinib on the survival of patients came from a non-randomized, retrospective analysis of the patients enrolled in the phase I study.[25] The one- and two-year survival rates for patients treated with crizotinib were 74 and 54%, respectively, with a median follow-up of 18 months. In a cohort of 36 patients with the ALK fusion oncogene, who were not treated with crizotinib, the survival rates at one- and two-years were 44 and 12%, respectively. A comparison with a larger cohort of patients with wild-type tumors did not identify a difference when compared with those with the ALK rearrangement not treated with crizotinib, suggesting that the presence of ALK rearrangement was not prognostically significant.

In another phase 1 trial,[26] the objective response rate among 116 evaluable patients was 61%. The median time to response was eight weeks, and as seen with the very first patient treated with crizotinib, rapid and dramatic responses were often noted by investigators. Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 10 months, similar to what was reported with EGFR inhibitors in advanced, EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Preliminary results from the phase 2 study were reported at the World Lung Congress in July 2011. Among 133 patients with advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC, the objective response rate was 51% and the disease control rate at 12 weeks was 74%. The follow up of phase 2 patients was too short to evaluate PFS. The 51 and 61% response rates were impressive, as the majority of phase 1 patients and all of the phase 2 patients were previously treated, and studies had shown a response rate of approximately 10% to standard second- and third-line chemotherapies in unselected patients with advanced NSCLC.[26]

The activity of crizotinib in ALK rearrangement positive NSCLC was subsequently confirmed in a phase III trial, in which 347 patients were randomly assigned to crizotinib or single agent chemotherapy with either pemetrexed or docetaxel.[27] Patients with progressive disease, on chemotherapy, were allowed to cross over and receive treatment with crizotinib. All patients had received one prior platinum-based regimen. The preliminary results were presented at the 2012 European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) meeting. Treatment with crizotinib significantly increased progression-free survival, the primary endpoint of the trial, compared to chemotherapy (median 7.7 versus 3.0 months, hazard ratio [HR] 0.49, 95% CI 0.37–0.64). There was no significant difference in the overall survival (median 20.3 versus 22.8 months, HR 1.02), but 64% of the chemotherapy-treated patients had crossed over to crizotinib.

In US, newly diagnosed patients are taken to a first-line study, PROFILE 1014, which is comparing crizotinib head-to-head with a platinum/pemetrexed combination in advanced ALK-positive NSCLC.[28] Patients who are initially randomized to standard chemotherapy will be able to cross over to crizotinib at the time of progression. Outside US, all ALK-positive patients must participate in a clinical trial in order to receive crizotinib. In addition to PROFILE 1014, there is also a second-line registration trial (PROFILE 1007) comparing crizotinib to a single agent, pemetrexed or docetaxel.[29] ALK-positive patients who are beyond the first- or second-line therapy can receive crizotinib through the ongoing phase 2 trial PROFILE 1005 [Table 1].[30]

An overview of the ongoing trials with ALK inhibitors are as follows

-

ALK inhibition, NSCLC

- PROFILE 1007: Phase 3 study of crizotinib versus chemotherapy (Pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 OR Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 Day 1, q21d) in previously treated Stage III/IV NSCLC (NCT00932893)

- PROFILE 1014: Ph III frontline study of crizotinib versus chemotherapy (Pemetrexed/cisplatin or pemetrexed/carboplatin) in previously untreated NSCLC (NCT01154140)

- PROFILE 1005: Ph II pretreated (NCT00932451)

- PROFILE 1001: Ph II expansion cohort (NCT00585195)

-

ALK inhibition, other tumor types

- PROFILE 1013: Phase 1b single-arm study in patients with ALK-positive non-NSCLC tumors: (NCT01121588)

-

Met inhibition

- Study 1002: Phase 1/2 erlotinib ± crizotinib (Met inhibition) in locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC with PD after one to two chemotherapies and no prior EGFR or c-MET/HGF inhibitors (NCT00965731)

These studies are still ongoing and the results of these studies may be a landmark in the history of targeted therapies and guide us in the treatment of NSCLC with these agents.

Indications

NSCLC: Locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that is anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positive (as detected by an approved test).

ALCL: There are case reports of complete responses to crizotinib in ALK-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Further studies of this agent in ALK-positive ALCL are underway.[31,32,33]

Myofibroblastic tumor: There are case reports of partial responses with crizotinib in an ALK-translocated inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT).[34]

Neuroblastoma: Crizotinib is also being tested in clinical trials of neuroblastoma. ALK mutations are thought to be important in driving the malignant phenotype in about 15% of the cases of neuroblastoma, a rare form of peripheral nervous system cancer that occurs almost exclusively in very young children.[35,36]

Dosing

ALK-positive NSCLC (locally advanced or metastatic): Oral: 250 mg twice daily, continue treatment until no longer clinically beneficial. It can be administered with or without food. If a dose is missed, take as soon as remembered, unless it is <6 hours prior to the next scheduled dose (skip the dose if <6 hours before the next dose); do not take two doses at the same time to make up for a missed dose.[37]

In renal impairment

Mild (ClCr 30-60 mL/minute) to moderate impairment (Clcr 60-90 mL/minute): No adjustment required

Severe impairment (Clcr <30 mL/minute): Data are insufficient to determine if dosage adjustment is necessary; use with caution

End-stage renal disease (ESRD): Was not studied in patients with ESRD; use with caution

In hepatic impairment

Data are insufficient to determine if dosage adjustment is necessary; however, crizotinib undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism, and systemic exposure may be increased with impairment; use with caution.

Dose adjustment for toxicity

If dose reduction is necessary, reduce dose to 200 mg orally twice daily; if necessary, further reduce to 250 mg once daily.

Hematological toxicity (except lymphopenia, unless lymphopenia is associated with clinical events such as opportunistic infection)

Grade 3 toxicity (WBC 1000-2000/mm3, ANC 5001000/mm3, platelets 25,000-50,000/mm3), grade 3 anemia: Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 2, then resume at the same dose and schedule

Grade 4 toxicity (WBC < 1000/mm3, ANC < 500/mm3, platelets < 25,000/mm3), grade 4 anemia: Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 2, then resume at 200 mg twice daily

Recurrent grade 4 toxicity on 200 mg twice daily: Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 2, then resume at 250 mg once daily

Recurrent grade 4 toxicity on 250 mg once daily: Permanently discontinue

Non-hematological toxicities

Grade 3 or 4 ALT or AST elevation (ALT or AST > 5 × ULN) with ≤ grade 1 total bilirubin elevation (total bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × ULN): Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 1 (<2.5 × ULN) or baseline, then resume at 200 mg twice daily

Recurrent grade 3 or 4 ALT or AST elevation with ≤ grade 1 total bilirubin elevation: Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 1, then resume at 250 mg once daily

Recurrent grade 3 or 4 ALT or AST elevation on 250 mg once daily: Permanently discontinue

Grade 2, 3, or 4 ALT or AST elevation with concurrent grade 2, 3, or 4 total bilirubin elevation (>1.5 × ULN) in the absence of cholestasis or hemolysis: Permanently discontinue

Pneumonitis (any grade; not attributable to disease progression, infection, other pulmonary disease or radiation therapy): Permanently discontinue

QTc prolongation

Grade 3 QTc prolongation (QTc >500 msec without life-threatening signs or symptoms): Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 1 (QTc ≤ 470 msec), then resume at 200 mg twice daily

Recurrent grade 3 QTc prolongation at 200 mg twice daily: Withhold treatment until recovery to ≤ grade 1, then resume at 250 mg once daily

Recurrent grade 3 QTc prolongation at 250 mg once daily: Permanently discontinue

Grade 4 QTc prolongation: Permanently discontinue

Adverse reactions

Significant > 10%

Cardiovascular: Edema (28%)

Central nervous system: Fatigue (20%), dizziness (16%)

Gastrointestinal: Nausea (53%), diarrhea (43%), vomiting (40%), constipation (27%), appetite decreased (19%), taste alteration (12%), esophageal disorder (11%; includes dyspepsia, dysphagia, epigastric burning/discomfort/pain, esophageal obstruction/pain/spasm/ulcer, esophagitis, gastroesophageal reflux, odynophagia, reflux esophagitis)

Hematological: Lymphopenia (grades 3/4: 11%)

Hepatic: ALT increased (13%; grades 3/4: 5%)

Neuromuscular and skeletal: Neuropathy (13%; grades 3/4: <1%)

Ocular: Vision disorder (62%; onset: <2 weeks; includes blurred vision, diplopia, photophobia, photopsia, visual acuity decreased, visual brightness, visual field defect, visual impairment, vitreous floaters)[37,38,39,40,41,42]

1% to 10%

Cardiovascular: Bradycardia (5%), chest pain (1%)

Central nervous system: Headache (4%), insomnia (3%)

Dermatological: Rash (10%)

Gastrointestinal: Abdominal pain (8%), stomatitis (6%)

Hematological: Neutropenia (grades 3/4: 5%)

Hepatic: AST increased (9%; grades 3/4: 2%)

Neuromuscular and skeletal: Arthralgia (2%)

Renal: Renal cysts (1%)

Respiratory: Cough (4%), dyspnea (2%), pneumonitis (2%), upper respiratory infection (2%)

Hypogonadism

<1% (Limited to important or life-threatening)

Back pain, fever, QTc prolongation, thrombocytopenia).

Resistance to crizotinib

The most frequent mutations involve the gatekeeper residue – amino acid substitutions at this position hinder drug binding and confer high-level resistance to many tyrosine-kinase inhibitors (TKIs). L1196M and L1152R mutations confer resistance to crizotinib via steric interference. Although crizotinib is not effective against EML4-ALK harboring the gatekeeper mutation, it has been observed that two structurally different ALK inhibitors, NVP-TAE684 and AP26113, are highly active against the resistant cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, these resistant cells remained highly sensitive to the Hsp90 inhibitor 17-AAG.[43]

Acquired resistance usually occurs within one year of starting crizotinib. Intrinsic resistance is possible in a small minority of patients. The frequency of these resistance mechanisms is not yet known.

Future Possibilities (Ongoing Cinical Trials)

Several second generation ALK inhibitors are under investigation in the clinic for patients with ALK-rearranged cancers. One of these, LDK378, is more potent and selective than crizotinib and may overcome acquired resistance. The preliminary results of the dose escalation phase 1 study of LDK378 have been reported at the 2012 ASCO meeting.[44] LDK378 has been tolerated reasonably well up to the MTD of 750 mg PO daily, with primarily GI side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Twenty-one of the 26 patients with crizotinib-resistant, ALK-positive NSCLC have achieved a RECIST partial response, yielding an objective response rate of 81%. Even though the duration of response has not been reported, the response rate alone suggests that the more potent ALK inhibitors like LDK378 may be useful in patients who relapse while on crizotinib. AP26113 is a structurally distinct second generation ALK TKI, which shows 5 times greater potency in vitro and in vivo when compared to crizotinib, in suppressing ALK phosphorylation and inducing apoptosis. Interestingly, it has also been shown to inhibit EGFR.[45] Other small molecule ALK inhibitors are in various stages of development.

The function of HSP is to stabilize proteins, for example, the fusion protein EML4-ALK. Preclinical studies have confirmed the sensitivity of cancer cell lines harboring ALK fusions to HSP90 inhibition. The phase II study of HSP90 inhibitor, AUY922, in patients with previously treated, advanced NSCLC, with primary endpoint of confirmed overall response rate (ORR) or stable disease (SD) at 18 weeks, of the ALK positive patients, two of the eight had PR (crizotinib-naïve) and SD was seen with tumor shrinkage (crizotinib-resistant).[43] Thus second-generation ALK TKIs or Hsp90 inhibitors are effective in treating crizotinib-resistant tumors harboring secondary gatekeeper mutations.

Conclusions

The presence of an ALK fusion oncogene defines a molecular subset of NSCLC with distinct clinical and pathological features. The patients most likely to harbor ALK rearrangement are relatively young, never or light smokers with adenocarcinoma. Whenever possible, therapy of patients with advanced NSCLC should be individualized, based on the molecular and histological features of the tumor. If feasible, patients should have the tumor tissue assessed for the presence of a somatic mutation in the EGFR, which confers sensitivity to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and to the ALK fusion oncogene, which is associated with sensitivity to crizotinib.

Thus, crizotinib is an important unmet medical need. It is a straightforward, biology-based biomarker, predicting a high response rate in heavily pre-treated patients and is relatively non-toxic. It is a triumph for a targeted therapy in the era of oncogenic driver mutations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mano H. Non-solid oncogenes in solid tumors: EML4-ALK fusion genes in lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2349–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn L, Pao W. EML4-ALK: Honing in on a new target in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4232–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi T, Sonobe M, Kobayashi M, Yoshizawa A, Menju T, Nakayama E, et al. Clinicopathologic features of non-small-cell lung cancer with EML4-ALK fusion gene. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:889–97. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0808-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw AT, Solomon B. Targeting anaplastic lymphoma kinase in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2081–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Soda M, Inamura K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, et al. Multiplex reverse transcription-PCR screening for EML4-ALK fusion transcripts. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6618–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi YL, Takeuchi K, Soda M, Inamura K, Togashi Y, Hatano S, et al. Identification of novel isoforms of the EML4-ALK transforming gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4971–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koivunen JP, Mermel C, Zejnullahu K, Murphy C, Lifshits E, Holmes AJ, et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4275–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Togashi Y, Soda M, Hatano S, Inamura K, et al. KIF5B-ALK, a novel fusion oncokinase identified by an immunohistochemistry-based diagnostic system for ALK-positive lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3143–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, Tam IY, Sihoe AD, Cheng LC, et al. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115:1723–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A Study Of Oral PF-02341066, A c-Met/Hepatocyte Growth Factor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor. Patients With Advanced Cancer. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 6]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00585195 .

- 12.Soda M, Takada S, Takeuchi K, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Ueno T, et al. A mouse model for EML4-ALK-positive lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19893–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805381105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosinesignaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y, Ren Y, Fang Z, Li C, Fang R, Gao B, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma from East Asian never-smokers is a disease largely defined by targetable oncogenic mutant kinases. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4616–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui JJ, Tran-Dube M, Shen H, Nambu M, Kung PP, Pairish M, et al. Structure based drug design of crizotinib (PF-02341066), a Potent and selective dual inhibitor of Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition Factor (c-MET) Kinase and Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) J Med Chem. 2011;54:6342–63. doi: 10.1021/jm2007613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martelli MP, Sozzi G, Hernandez L, Pettirossi V, Navarro A, Conte D, et al. EML4-ALK rearrangement in non-small cell lung cancer and non-tumor lung tissues. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:661–70. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boland JM, Erdogan S, Vasmatzis G, Yang P, Tillmans LS, Johnson MR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunoreactivity correlates with ALK gene rearrangement and transcriptional up-regulation in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, Digumarthy SR, Costa DB, Heist RS, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perner S, Wagner PL, Demichelis F, Mehra R, Lafargue CJ, Moss BJ, et al. EML4-ALK fusion lung cancer: A rare acquired event. Neoplasia. 2008;10:298–302. doi: 10.1593/neo.07878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodig SJ, Mino-Kenudson M, Dacic S, Yeap BY, Shaw A, Barletta JA, et al. Unique clinicopathologic features characterize ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinoma in the western population. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5216–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mino-Kenudson M, Chirieac LR, Law K, Hornick JL, Lindeman N, Mark EJ, et al. A novel, highly sensitive antibody allows for the routine detection of ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinomas by standard immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1561–71. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, Iafrate AJ, Varella-Garcia M, Fox SB, et al. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1011–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70344-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Solomon BJ, Riely GJ, Gainor J, Engelman JA, et al. Effect of crizotinib on overall survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring ALK gene rearrangement: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1004–12. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camidge DR, Bang Y, Kwak EL, Shaw A, Iafrate AJ, Maki RG, et al. Progression-free survival (PFS) from a phase 1 study of crizotinib (PF-02341066) in patients with ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2501. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Phase III study of crizotinib versus pemetrexed or docetaxel chemotherapy in patients with advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (abstract LBA1 PR) Eur Soc Med Oncol Meet. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phase 3, Randomized, Open-Label Study Of The Efficacy And Safety Of Crizotinib Versus Pemetrexed/Cisplatin Or Pemetrexed/Carboplatin In Previously Untreated Patients With Non-Squamous Carcinoma Of The Lung Harboring A Translocation Or Inversion Event Involving The Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) Gene Locus. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 6]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01154140 .

- 29.An Investigational Drug, PF-02341066 Is Being studied versus standard of care in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer with a specific gene profile involving the Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) Gene. [Last accessed on 2013 Feb 11]. Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00932893 .

- 30.Crinò L, Kim D, Riely GJ, Janne PA, Blackhall FH, Camidge DR, et al. Initial phase II results with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): PROFILE 1005. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl) abstr 7514. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambacorti-Passerini C, Messa C, Pogliani EM. Crizotinib in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:775–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1013224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pogliani EM, Dilda I, Villa F, Farina F, Giudici G, Guerra L, et al. Gambacorti-Passerini. High response rate to crizotinib in advanced, chemoresistant ALK+lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl) abstr e18507. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foyil KV, Bartlett NL. Brentuximabvedotin and crizotinib in anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Cancer J. 2012;18:450–6. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31826aef4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butrynski JE, D’Adamo DR, Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Antonescu CR, Jhanwar SC, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:172–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janoueix-Lerosey I, Schleiermacher G, Delattre O. Molecular pathogenesis of peripheral neuroblastic tumors. Oncogene. 2010;29:1566–79. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood AC, Laudenslager M, Haglund EA, Attiyeh EF, Pawel B, Courtright J, et al. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA; Pfizer Global Research and Development, San Diego, CA “Inhibition of ALK mutated neuroblastomas by the selective inhibitor PF-02341066. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(Suppl):15s. abstr 10008b. [Google Scholar]

- 37.FDA. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 6]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfdadocs/label/2011/202570s000lbl.pdf .

- 38.Besse B, Salgia R, Solomon B, Shaw A, Kim D, Schachar R, et al. Visual disturbances in patients (Pts) With Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (Alk)-positive advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Nsclc) treated with crizotinib (Abstract 1268p) Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnell P, Safferman AZ, Bartlett CH, Tang Y, Wilner KD. Clinical presentation of hepatotoxicity-associated crizotinib in ALK-positive (ALK+) advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl) abstr 7598. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ou SH, Azada M, Dy J, Stiber JA. Asymptomatic profound sinus bradycardia (heart rate ≤ 45) in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:2135–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramalingam SS, Shaw AT. Hypogonadism related to crizotinib therapy: Implications for patient care. Cancer. 2012;118:e1–2. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weickhardt AJ, Rothman MS, Salian-Mehta S, Kiseljak-Vassiliades K, Oton AB, Doebele RC, et al. Rapid-onset hypogonadism secondary to crizotinib use in men with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5302–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sasaki T, Koivunen J, Ogino A, Yanagita M, Nikiforow S, Zheng W, et al. A novel ALK secondary mutation and EGFR signaling cause resistance to ALK kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6051–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehra R, Camidge DR, Sharma S, Felip E, Tan DS, Vansteenkiste JF, et al. First-in-human phase I study of the ALK inhibitor LDK378 in advanced solid tumors (abstract #3007) J Clin Oncol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katayama R, Khan TM, Benes C, Lifshits E, Ebi H, Rivera VM, et al. Therapeutic strategies to overcome crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancers harboring the fusion oncogene EML4-ALK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7535–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]