Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is mainly caused by mutations in the X-linked methyl-CpG binding protein (MeCP2) gene. By binding to methylated promoters on CpG islands, MeCP2 protein is able to modulate several genes and important cellular pathways. Therefore, mutations in MeCP2 can seriously affect the cellular phenotype. Today, the pathways that MeCP2 mutations are able to affect in RTT are not clear yet. The aim of our study was to investigate the gene expression profiles in peripheral blood lymphomonocytes (PBMC) isolated from RTT patients to try to evidence new genes and new pathways that are involved in RTT pathophysiology. LIMMA (Linear Models for MicroArray) and SAM (Significance Analysis of Microarrays) analyses on microarray data from 12 RTT patients and 7 control subjects identified 482 genes modulated in RTT, of which 430 were upregulated and 52 were downregulated. Functional clustering of a total of 146 genes in RTT identified key biological pathways related to mitochondrial function and organization, cellular ubiquitination and proteosome degradation, RNA processing, and chromatin folding. Our microarray data reveal an overexpression of genes involved in ATP synthesis suggesting altered energy requirement that parallels with increased activities of protein degradation. In conclusion, these findings suggest that mitochondrial-ATP-proteasome functions are likely to be involved in RTT clinical features.

1. Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a rare form of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which mostly affects girls with worldwide prevalence rate ranges from 1 : 10,000 to 1 : 20,000 live births [1–5]. RTT is a clinically defined condition with a large spectrum of phenotypes associated with a wide genotypic variability [6, 7]. Classic or typical RTT, the most common form of the condition, is caused in about 90–95% of cases by de novo mutations in the MeCP2, a gene mapped on chromosome X and encoding methyl-CpG binding protein 2 [7, 8]. The clinical picture of classical form progresses through 4 stages and is characterized by normal development for the first 6 to 18 months, followed by loss of purposeful hand movements, failure of speech development, autistic-like behavior, slowed brain and head growth, and mental retardation [9].

To date, it is not known how MeCP2 mutations lead to RTT phenotypes; therefore the identification of the pathways that are affected by MeCP2 functions could bring new insight in the RTT pathogenetic mechanisms. MeCP2 was originally thought to function as a transcription repressor by binding to methylated CpG dinucleotides, but recent studies have individuated more functions related to MeCP2 [10, 11]. In fact MeCP2 is now considered a multifunctional protein, since it is implicated not only in genome transcriptional silencing, but also in transcriptional activation, by regulating chromatin and nuclear architecture [11]; therefore, its malfunction or mutation can lead to severe cellular function alterations.

Hence, it is very difficult to understand the link between MeCP2 mutation and the clinical feature present in RTT. One of the most common approaches used to better understand the molecular pathways involved in genetic disorders has been the determination of gene expression profiling, since it provides the opportunity to evaluate possible transcriptome alterations at both gene and gene-network levels. This approach should not be considered an end point but a magnifying lent where new aspects involved in the diseases can be discovered and then studied.

So far, only a handful of studies have investigated the gene expression profiles of RTT children in tissues, that is, postmortem brain samples [12], or in cells, such as clones of fibroblasts isolated from skin biopsies [13, 14] and immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines [14–16]. Moreover, several studies have performed microarray gene expression analysis using in vitro cellular models representing MeCP2 deficiency induced by siRNAs [17] or cells and tissues from RTT mouse models [18], but to our knowledge there are no data on microarray analysis from “ex vivo” fresh samples. For this reason, the aim of this study was to evaluate the gene expression patterns in PBMC isolated from RTT patients. This approach lets us bypass some of the limitations/variables of the previous gene arrays studies on RTT, such as the use of postmortem samples, gene-modified cells and murine tissues that do not always reflect all features of the human disease. In fact, studying ex vivo samples, such as PBMC, provides some advantage that can be summarized by the fact PBMC are the only readily available cells in humans; various studies showed disease-characteristic gene expression patterns in PBMC that can be easily obtained.

Our results identified a clear difference in gene expression profile between control and RTT patients, with almost 500 genes being deregulated, suggesting several new pathways involved in this disorder.

2. Subjects and Methods

2.1. Subjects Population

The study included 12 female patients with clinical diagnosis of typical RTT (mean age: 10.9 ± 4.9 years, range: 6–22) with demonstrated MeCP2 gene mutation and 7 sex- and age-matched healthy controls (mean age: 15.1 ± 9.03 years, range: 4–32). RTT diagnosis and inclusion/exclusion criteria were based on the recently revised RTT nomenclature consensus [4]. All the patients were consecutively admitted to the Rett Syndrome National Reference Centre of the University Hospital of the Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Senese (AOUS). Table 1 presents the demographic and genetic characteristics of the enrolled patients subjected to microarray analysis. Blood sampling in the control group was carried out during routine health checks, sports, or blood donations, while blood sample in patients were obtained during the periodic clinical checks. The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board and all informed consents were obtained from either the parents or the legal tutors of the enrolled patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and genetic data for RTT patients enrolled in study.

| No. | Age | Stage | Mutation type | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 7 | 3 | ETMs | ||

| #2 | 10 | 3 | missense | c.403A>G | p.K135E |

| #3 | 9 | 4 | missense | c.403A>G | p.K135E |

| #4 | 9 | 4 | missense | c.455C>G | p.P152R |

| #5 | 12 | 3 | missense | c.473C>T | p.T158M |

| #6 | 19 | 3 | nonsense | c.763C>T | p.R255X |

| #7 | 22 | 3 | frameshift insertion or deletion | c.806_807delG | p.G269fs |

| #8 | 7 | 4 | nonsense | c.808C>T | p.R270X |

| #9 | 7 | 3 | nonsense | c.808C>T | p.R270X |

| #10 | 12 | 4 | nonsense | c.880C>T | p.R294X |

| #11 | 6 | 3 | nonsense | c.880C>T | p.R294X |

| #12 | 11 | 3 | missense | c.916C>T | p.R306C |

ETMs: early truncating mutations.

2.2. Blood Specimen Collection, Peripheral Blood Lymphomonocytes Isolation, and RNA Extraction

Blood was collected in heparinized tubes and all manipulations were carried out within 30 minutes after sample collection. PBMC were separated from whole blood by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Milan, Italy). After PBMC isolation, total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total nucleic acid concentration and purity were estimated using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Quality of RNA was checked on Agilent bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The isolated RNA samples were stored at −80°C until the analysis.

2.3. Microarray Processing

For the microarray processing, RNA was amplified and labeled using the Affymetrix Whole-Transcript (WT) Sense Target Labeling Protocol. Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays were hybridized with labeled sense DNA, washed, stained, and scanned according to the protocol described in WT Sense Target Labeling Assay Manual.

Briefly, 100 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed into double-stranded cDNA with random hexamers tagged with a T7 promoter sequence. The double-stranded cDNA was subsequently used as a template and amplified by T7 RNA polymerase, producing many copies of antisense cRNA. In the second cycle of cDNA synthesis, random hexamers were used to prime reverse transcription of the cRNA from the first cycle to produce single-stranded DNA in the sense orientation. dUTP was incorporated in the DNA during the second-cycle, first-strand reverse transcription reaction. This single-stranded DNA sample was then treated with a combination of uracil DNA glycosylase (UDG) and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE 1) that specifically recognized the unnatural dUTP residues and broke the DNA strand. DNA was labeled by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) with the Affymetrix proprietary DNA Labeling Reagent that is covalently linked to biotin. 5 μg of labeled cDNA was hybridized to the Human Gene 1.0 ST Array at 45°C for 17 hours. The arrays were washed and stained in Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 and scanned using the Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000.

2.4. Microarray Data Analysis

The microarray experiments were analyzed with the oneChannelGUI package available in R software. The signal intensities from each chip were preliminarily normalized with RMA method and filtered by IQR filter choosing as threshold a value of 0.25. This specific filter removes the probesets that do not present changes in their expression across the analyzed microarray. The threshold of 0.25 is an intermediate value that retains the probesets that show significative changes of their signal at least in the 25% of analyzed microarray. The microarray data were analyzed by SAM and LIMMA analyses. SAM approach uses permutation based statistics and is a valid method to analyze data that may not follow a normal distribution, outperforming other techniques (e.g., ANOVA and classical t-test), which assume equal variance and/or independence of genes. LIMMA fit each gene expression to a linear regression model testing the significativity of the distance from the model with a t-test robust against nonnormality and inequality of variances. In order to characterize the biological processes enriched in the list of modulated genes, a statistical analysis of overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) terms (BP level 5) was performed with DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery) web server (DAVID Bioinformatics Resources) [19]. Only the GO terms enriched with a P value < 0.05 corrected with the Benjamini and Hochberg method [20] were selected and hierarchically clusterized (Ward's method) according to their “semantic” similarity estimated with the GOSIM R package with default parameters. After clusterization the best number of clusters was identified according to the analysis of the silhouette scores and the medoid term in each cluster was selected as the representative member of the cluster. Each cluster represents a group of biological processes with similar e/o related functions.

2.5. Validation of Microarray Data by RT-qPCR (Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real-Time PCR)

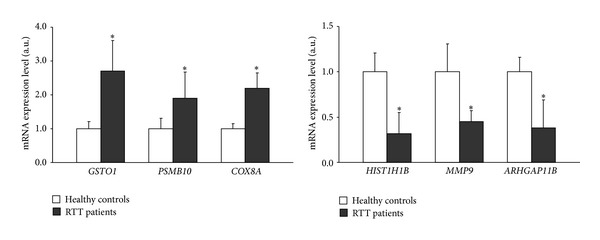

For confirmation of Affymetrix expression microarray results, RT-qPCR analysis was performed as previously described [21]. For validation, six of the differentially expressed genes, 3 upregulated—GSTO1, PSMB10 and COX8A—and 3 downregulated—HIST1H1B, MMP9 and ARHGAP11B—by microarray, were chosen. Validation was done in a randomly selected subset of the original samples (submitted for microarray analysis) that included 3 healthy controls and 3 RTT patients. Primer pairs were obtained from the Real-time PCR GenBank Primer to hybridise unique regions of the appropriate gene sequence: GSTO1 (Fw: 5′-AGA GTT GTT TTC TAA GGT TCT GAC T-3′) and (RW: 5′-ACT TCA TTG CTT CCA GCC GT-3′), product length 116 bp; PSMB10 (Fw: 5′-ACA GAC GTG AAG CCT AGC AG-3′) and (Rw: 5′-ACC GAA TCG TTA GTG GCT CG-3′), product length 294 bp; COX8A (Fw: 5′-GCC AAG ATC CAT TCG TTG CC-3′) and (RW: 5′-TCT GGC CTC CTG TAG GTC TC-3′), product length 137 bp; HIST1H1B (Fw: 5′-CCC GGC TAA GAA GAA GGC AA-3′) and (RW: 5′-ACA GCC TTG GTG ATC AGC TC-3′), product length 99 bp; MMP9 (Fw: 5′-GTC CGT GAG GGT GTT GAG TG-3′) and (RW: 5′-ACT GCT CAA AGC CTC CAC AA-3′), product length 145 bp; ARHGAP11B (Fw: 5′-AAC TGC CAG AGC CCA TTC TC-3′) and (RW: 5′-GTC TGG TAC ACG CCC TTC TT-3′), product length 295 bp. All reactions were run in triplicate. GAPDH (FW: 5′-TGA CGC TGG GGC TGG CAT TG-3′ and RW: 5′-GGC TGG TGG TCC AGG GGT CT-3′, 134 pb) was used in our experiments as internal standard. As previously described, samples were compared using the relative cycle threshold (CT) method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). After normalization to more stable mRNA GAPDH, the fold increase or decrease was determined with respect to control, using the formula 2−ΔΔCT, where ΔCT is (gene of interest CT)−(reference gene CT) and ΔΔCT is (ΔCT experimental)−(ΔCT control). Results are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments, each analysed in triplicate. *P < 0.001 versus control (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's posttest).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Differentially Regulated Genes in RTT Patients

Given that RTT results from dysfunction of the transcriptional modulator MeCP2, several strategies have been developed to identify its target genes in order to gain insights into the disease pathogenesis [12–18]. In our study, to identify gene expression changes associated with and potentially related to MeCP2 mutations and to delineate alterations of pathways associated with the disease, we evaluated and compared transcriptomic profiles in PBMC from RTT patients and control subjects.

This work showed for the first time, to our knowledge, altered expression of a large set of genes that may help elucidating and explaining the link between MeCP2 and some of the molecular and cellular aspects observed in RTT patients. In our previous studies on RTT we were able to show increased levels of oxidative stress (OS) markers, such as isoprostanes (IsoPs) and 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts (4-HNE PAs) [22, 23], and increased ubiquitination and degradation of oxidatively modified proteins [24], but how MeCP2 mutation is able to affect cellular redox balance and proteins turn over still needs to be defined.

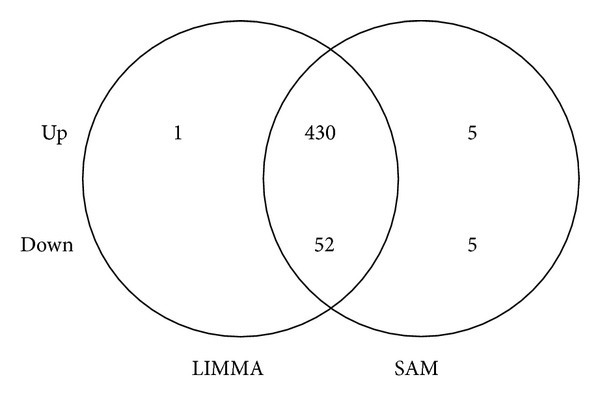

Using the SAM and LIMMA methods, we have defined a set of genes differentially expressed in RTT patients with respect to controls (healthy subjects) and a significant overlap was found by comparing results from two approaches. A cut-off level based on a minimum of 1-fold change in expression resulted in a list of 482 common deregulated genes, while 10 genes were suggested only by SAM and only 1 gene was indicated by LIMMA. Among the shared genes, 430 showed significant upregulation, while 52 were downregulated in RTT compared to controls (Figure 1 and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). The 11 genes indicated by only one method were excluded for further analysis. Genes with the strongest changes in expression, both upregulated (FC ≥ 2) and downregulated (FC ≤ −1.2), are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The complete list of differentially expressed genes, both upregulated and downregulated (FC ± 1), is shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of two distinct approaches for screening of differentially expressed genes in RTT PBMC. Venn diagram representing numbers of common and exclusively up- and downregulated genes for LIMMA (left) and SAM (right) analyses (FC ± 1; adj. P value ≤ 0.05). The 11 genes indicated by only one method were excluded by further analysis.

Table 2.

Genes upregulated in RTT patients by LIMMA and SAM analyses.

| NCBI reference sequence | Gene symbol | Gene name | Molecular function | Biological process | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_004541.3 | NDUFA1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 1, 7.5 kDa | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity | Mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone | 3.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_006498.2 | LGALS2 | Lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 2 | Carbohydrate binding | — | 2.8 |

|

| |||||

| NM_014302.3 | SEC61G | Sec61 gamma subunit | Protein transporter activity | Protein targeting to ER; antigen processing and presentation of exogenous peptide antigen via MHC class I | 2.8 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001040437.1 | C6orf48 | Chromosome 6 open reading frame 48 | — | — | 2.7 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001098577.2 | RPL31 | Ribosomal protein L31 | RNA binding; structural constituent of ribosome | Translational elongation; translational initiation; translational termination | 2.7 |

|

| |||||

| NM_006989.5 | RASA4 | RAS p21 protein activator 4 | GTPase activator activity; phospholipid binding | Intracellular signal transduction; positive regulation of GTPase activity; regulation of small GTPase mediated signal transduction | 2.6 |

|

| |||||

| NM_000983.3 | RPL22 | Ribosomal protein L22 | RNA binding; heparin binding; structural constituent of ribosome | Alpha-beta T cell differentiation; translational elongation; translational initiation; translational termination | 2.6 |

|

| |||||

| NM_019059.3 | TOMM7 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 7 homolog (yeast) | Protein transmembrane transporter activity | Cellular protein metabolic process; protein import into mitochondrial matrix; protein targeting to mitochondrion | 2.6 |

|

| |||||

| NM_031157.2 | HNRNPA1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | Nucleotide binding; single-stranded DNA binding; single-stranded RNA binding | RNA export from nucleus; mRNA splicing, via spliceosome; mRNA transport; nuclear import | 2.5 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001828.5 | CLC | Charcot-Leyden crystal galectin | Carbohydrate binding; carboxylesterase activity; lysophospholipase activity | Lipid catabolic process; multicellular organismal development | 2.4 |

|

| |||||

| NM_032901.3 | COX14 | Cytochrome c oxidase assembly homolog 14 (S. cerevisiae) | Plays a role in the assembly or stability of the cytochrome c oxidase complex (COX) | Mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV assembly | 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NM_024960.4 | PANK2 | Pantothenate kinase 2 | ATP binding; pantothenate kinase activity | Cell death; coenzyme A biosynthetic process; coenzyme biosynthetic process; pantothenate metabolic process | 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NR_002309.1 | RPS26P11 | Ribosomal protein S26 pseudogene 11 | Structural constituent of ribosome | Translation | 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NM_005003.2 | NDUFAB1 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1, alpha/beta subcomplex, 1, 8 kDa | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity; ACP phosphopantetheine attachment site binding involved in fatty acid biosynthetic process; fatty acid binding; calcium ion binding | Cellular metabolic process; protein lipoylation; small molecule metabolic process; respiratory electron transport chain; fatty acid biosynthetic process; mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone | 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NM_152851.2 | MS4A6A | Membrane-spanning 4-domains, subfamily A, member 6A | May be involved in signal transduction as a component of a multimeric receptor complex | — | 2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004269.3 | MED27 | Mediator complex subunit 27 | Transcription coactivator activity | Regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter; stem cell maintenance; transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NR_015404.1 | C12orf47 | MAPKAPK5 antisense RNA 1 | — | — | 2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001865.3 | COX7A2 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIa polypeptide 2 (liver) | Cytochrome-c oxidase activity; electron carrier activity | Oxidative phosphorylation | 2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004374.3 | COX6C | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIc | Cytochrome-c oxidase activity | Respiratory electron transport chain; small molecule metabolic process | 2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002984.2 | CCL4 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | Chemokine activity | Cell adhesion; cell-cell signaling; chemotaxis; immune response; inflammatory response; positive regulation of calcium ion transport; positive regulation of calcium-mediated signaling; positive regulation of natural killer cell chemotaxis; response to toxic substance; response to virus; signal transduction |

2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_014060.2 | MCTS1 | Malignant T cell amplified sequence 1 | RNA binding | Cell cycle; positive regulation of cell proliferation; regulation of growth; regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent; response to DNA damage stimulus transcription, DNA-dependent | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004832.2 | GSTO1 | Glutathione S-transferase omega 1 | Glutathione dehydrogenase (ascorbate) activity; glutathione transferase activity; methylarsonate reductase activity | L-ascorbic acid metabolic process; glutathione derivative biosynthetic process; negative regulation of ryanodine-sensitive calcium-release channel activity; positive regulation of ryanodine-sensitive calcium-release channel activity; positive regulation of skeletal muscle contraction by regulation of release of sequestered calcium ion; regulation of cardiac muscle contraction by regulation of the release of sequestered calcium ion; xenobiotic catabolic process | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001867.2 | COX7C | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIc | Cytochrome-c oxidase activity | Respiratory electron transport chain; small molecule metabolic process | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_014206.3 | C11orf10 | Transmembrane protein 258 | — | — | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002413.4 | MGST2 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2 | Enzyme activator activity; glutathione peroxidase activity; glutathione transferase activity; leukotriene-C4 synthase activity | Glutathione biosynthetic process; glutathione derivative biosynthetic process; leukotriene biosynthetic process; positive regulation of catalytic activity; xenobiotic metabolic process | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001124767.1 | C3orf78 | Small integral membrane protein 4 | — | — | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_152398.2 | OCIAD2 | OCIA domain containing 2 | — | — | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002488.4 | NDUFA2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 2, 8 kDa | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity | Mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone small molecule metabolic process | 2.1 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004528.3 | MGST3 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 | Glutathione peroxidase activity; glutathione transferase activity |

Glutathione derivative biosynthetic process; lipid metabolic process; signal transduction; small molecule metabolic process xenobiotic metabolic process |

2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_003095.2 | SNRPF | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide F | RNA binding | Histone mRNA metabolic process; mRNA 3′-end processing ncRNA metabolic process; spliceosomal snRNP assembly; termination of RNA polymerase II transcription |

2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_005213.3 | CSTA | Cystatin A (stefin A) | Cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor activity; protein binding, bridging structural molecule activity |

Cell-cell adhesion; keratinocyte differentiation; peptide cross-linking | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_033318.4 | C22orf32 | Single-pass membrane protein with aspartate-rich tail 1 | — | — | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_053035.2 | MRPS33 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S33 | Structural constituent of ribosome | Translation | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| BC014670.1 | LOC147727 | Hypothetical protein LOC147727, mRNA (cDNA clone IMAGE: 4864993), partial cds | — | — | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001014.4 | RPS10 | Ribosomal protein S10 | Protein binding | Translational elongation; translational initiation; translational termination; viral transcription | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001130710.1 | LSM5 | LSM5 homolog, associated U6 small nuclear RNA (S. cerevisiae) | RNA binding | RNA splicing; exonucleolytic nuclear-transcribed mRNA catabolic process involved in deadenylation-dependent decay; mRNA processing |

2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002801.3 | PSMB10 | Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type, 10 | Threonine-type endopeptidase activity | DNA damage response, signal transduction by p53 class mediator resulting in cell cycle arrest; G1/S transition of mitotic cell cycle; T cell proliferation; anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process; apoptotic process; cell morphogenesis; gene expression; humoral immune response; mRNA metabolic process; negative regulation of apoptotic process; negative regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity involved in mitotic cell cycle; positive regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity involved in mitotic cell cycle; protein polyubiquitination; regulation of cellular amino acid metabolic process; small molecule metabolic process | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_014044.5 | UNC50 | Unc-50 homolog (C. elegans) | RNA binding | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway; protein transport | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_032747.3 | USMG5 | Up-regulated during skeletal muscle growth 5 homolog (mouse) | Plays a critical role in maintaining the ATP synthase population in mitochondria | — | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001001330.2 | REEP3 | Receptor accessory protein 3 | May enhance the cell surface expression of odorant receptors | — | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004074.2 | COX8A | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIIA (ubiquitous) | Cytochrome-c oxidase activity | Respiratory electron transport chain; small molecule metabolic process | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002493.4 | NDUFB6 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 beta subcomplex, 6, 17 kDa | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) activity | Mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone; small molecule metabolic process | 2.0 |

|

| |||||

| NM_032273.3 | TMEM126A | Transmembrane protein 126A | — | Optic nerve development | 2.0 |

“—”: lacking item.

Table 3.

Genes down-regulated in RTT patients by LIMMA and SAM analyses.

| NCBI reference sequence | Gene symbol | Gene name | Molecular function | Biological process | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_170601.4 | SIAE | Sialic acid acetylesterase | Sialate O-acetylesterase activity | — | −2.3 |

|

| |||||

| NR_002312.1 | RPPH1 | Ribonuclease P RNA component H1 | — | — | −2.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_005322.2 | HIST1H1B | Histone cluster 1, H1b | DNA binding | Nucleosome assembly | −1.8 |

|

| |||||

| NM_000902.3 | MME | Membrane metalloendopeptidase | Metalloendopeptidase activity | Proteolysis | −1.8 |

|

| |||||

| NM_032047.4 | B3GNT5 | UDP-GlcNAc: betaGal beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 5 | Galactosyltransferase activity | Glycolipid biosynthetic process; posttranslational protein modification | −1.7 |

|

| |||||

| NM_003513.2 | HIST1H2AB | Histone cluster 1, H2ab | DNA binding | Nucleosome assembly | −1.7 |

|

| |||||

| NR_002562.1 | SNORD28 | Small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 28 | — | — | −1.5 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004668.2 | MGAM | Maltase-glucoamylase (alpha-glucosidase) | Alpha-glucosidase activity; amylase activity | Carbohydrate metabolic process | −1.5 |

|

| |||||

| NM_012081.5 | ELL2 | Elongation factor, RNA polymerase II, 2 | — | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | −1.4 |

|

| |||||

| NM_021066.2 | HIST1H2AJ | Histone cluster 1, H2aj | DNA binding | nucleosome assembly | −1.4 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002424.2 | MMP8 | Matrix metallopeptidase 8 (neutrophil collagenase) | Metalloendopeptidase activity; zinc ion binding | Proteolysis | −1.4 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004994.2 | MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (gelatinase B, 92 kDa, gelatinase, 92 kDa, type IV collagenase) | Collagen binding; metalloendopeptidase activity; zinc ion binding | Collagen catabolic process; extracellular matrix disassembly; positive regulation of apoptotic process; proteolysis |

−1.4 |

|

| |||||

| NM_003533.2 | HIST1H3I | Histone cluster 1, H3i | DNA binding | Nucleosome assembly; regulation of gene silencing | −1.3 |

|

| |||||

| NG_000861.4 | GK3P | Glycerol kinase 3 pseudogene | ATP binding; glycerol kinase activity | Catabolic process; glycerol metabolic process | −1.3 |

|

| |||||

| NR_033423.1 | LOC1720 | Dihydrofolate reductase pseudogene | — | — | −1.3 |

|

| |||||

| NM_003521.2 | HIST1H2BM | Histone cluster 1, H2bm | DNA binding | Nucleosome assembly | −13 |

|

| |||||

| NM_002417.4 | MKI67 | Antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki-67 | ATP binding | DNA metabolic process; cell proliferation; cellular response to heat; meiosis; organ regeneration | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_020406.2 | CD177 | CD177 molecule | — | Blood coagulation; leukocyte migration | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001039841.1 | ARHGAP11B | Rho GTPase activating protein 11B | GTPase activator activity | Positive regulation of GTPase activity; regulation of small GTPase mediated signal transduction; small GTPase mediated signal transduction | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001004690.1 | OR2M5 | Olfactory receptor, family 2, subfamily M, member 5 | G-protein coupled receptor activity; olfactory receptor activity | Detection of chemical stimulus involved in sensory perception of smell | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_052966.3 | FAM129A | Family with sequence similarity 129, member A | — | Negative regulation of protein phosphorylation; positive regulation of protein phosphorylation; positive regulation of translation; response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_001067.3 | TOP2A | Topoisomerase (DNA) II alpha 170 kDa | ATP binding; DNA binding, bending; chromatin binding; drug binding; magnesium ion binding; ubiquitin binding | DNA ligation; DNA repair; DNA topological change; DNA-dependent DNA replication; apoptotic chromosome condensation; mitotic cell cycle; phosphatidylinositol-mediated signaling; positive regulation of apoptotic process; positive regulation of retroviral genome replication; positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter; sister chromatid segregation | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_021018.2 | HIST1H3F | Histone cluster 1, H3f | DNA binding | S phase; blood coagulation; nucleosome assembly; regulation of gene silencing |

−1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_182707.2 | PSG8 | Pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein 8 | The human pregnancy-specific glycoproteins (PSGs) are a group of molecules that are mainly produced by the placental syncytiotrophoblasts during pregnancy. PSGs comprise a subgroup of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family, which belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily. |

Female pregnancy | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_003535.2 | HIST1H3J | Histone cluster 1, H3j | DNA binding | S phase; blood coagulation; nucleosome assembly; regulation of gene silencing |

−1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_004566.3 | PFKFB3 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 | 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase activity; ATP binding; fructose-2,6-bisphosphate 2-phosphatase activity | Fructose metabolic process; glycolysis; small molecule metabolic process | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NM_016448.2 | DTL | Denticleless E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase homolog (Drosophila) | — | DNA replication; G2 DNA damage checkpoint; protein monoubiquitination; protein polyubiquitination; ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NG_001019.5 | IGHM | Immunoglobulin heavy constant mu | Antigen binding | Immune response | −1.2 |

|

| |||||

| NR_002907.2 | SNORA73A | Small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 73A | — | — | −1.2 |

“—”: lacking item.

It is evident from this first set of data that mutations in MeCP2 influence more the genes upregulation with respect to the downregulation. This is in part in line with the first functions that have been attributed to MeCP2, such as a gene expression repressor [10, 11]. In addition, it is worth it to underline that both screening approaches used in this study (LIMMA and SAM) almost overlap between them making the results more reliable.

Next, using the DAVID databases, we performed the functional annotation of the significant genes and identification of the biochemical pathways in which they are involved. A comparison of the differentially regulated mRNA transcripts in RTT PBMC compared to control group shows significant changes in cellular pathways. In particular, we identify 10 major clusters corresponding to 62 biological processes enriched by 146 genes (Table 4). These clusters highlight key biological pathways related to mitochondrial function and organization (i.e., mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled to electron transport, inner mitochondrial membrane organization such as: ATP5A1, COX6C, ETFA, UQCRQ, TIMM10, and TSPO), cellular protein metabolic process (i.e., regulation of protein ubiquitination, regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity, and proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process such as PSMA2, PSMD6, UBE2E3, and UFC), RNA processing (i.e., nuclear mRNA splicing and spliceosome assembly and RNA elongation from RNA polymerase II promoter such as RPL15), DNA organization in chromatin, and cellular macromolecular complex assembly (i.e., nucleosome assembly, DNA packaging, and protein complex biogenesis such as HIST1H4L, H2AFZ, TOP2A, and HMGB2).

Table 4.

GO analysis of genes reported to be deregulated in PBMC of RTT patients.

| Term | Description | P value | Fold enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | |||

| GO:0022900 | Electron transport chain | 2.0 × 10−12 | 9.01 |

| GO:0006091 | Generation of precursor metabolites and energy | 1.7 × 10−12 | 5.06 |

| GO:0045333 | Cellular respiration | 2.7 × 10−12 | 9.71 |

| GO:0006120 | Mitochondrial electron transport, NADH to ubiquinone | 4.9 × 10−12 | 16.32 |

| GO:0022904 | Respiratory electron transport chain | 1.8 × 10−11 | 12.04 |

| GO:0006119 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 2.0 × 10−11 | 9.17 |

| GO:0042775 | Mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled electron transport | 2.0 × 10−11 | 12.99 |

| GO:0042773 | ATP synthesis coupled electron transport | 2.0 × 10−11 | 12.99 |

| GO:0015980 | Energy derivation by oxidation of organic compounds | 3.4 × 10−9 | 6.54 |

| GO:0055114 | Oxidation reduction | 1.5 × 10−8 | 3.01 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 2 | |||

| GO:0006626 | Protein targeting to mitochondrion | 4.3 × 10−3 | 8.81 |

| GO:0070585 | Protein localization in mitochondrion | 4.3 × 10−3 | 8.81 |

| GO:0045039 | Protein import into mitochondrial inner membrane | 7.5 × 10−3 | 28.54 |

| GO:0007007 | Inner mitochondrial membrane organization | 2.8 × 10−2 | 19.03 |

| GO:0006839 | Mitochondrial transport | 3.1 × 10−2 | 4.96 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 3 | |||

| GO:0051436 | Negative regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity during mitotic cell cycle | 1.8 × 10−4 | 7.24 |

| GO:0051444 | Negative regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity | 2.1 × 10−4 | 7.03 |

| GO:0051352 | Negative regulation of ligase activity | 2.1 × 10−4 | 7.03 |

| GO:0051437 | Positive regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity during mitotic cell cycle | 2.4 × 10−4 | 6.92 |

| GO:0051443 | Positive regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity | 2.8 × 10−4 | 6.73 |

| GO:0051439 | Regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity during mitotic cell cycle | 3.0 × 10−4 | 6.63 |

| GO:0051351 | Positive regulation of ligase activity | 3.7 × 10−4 | 6.45 |

| GO:0051438 | Regulation of ubiquitin-protein ligase activity | 6.2 × 10−4 | 6.04 |

| GO:0051340 | Regulation of ligase activity | 8.4 × 10−4 | 5.81 |

| GO:0043086 | Negative regulation of catalytic activity | 8.4 × 10−3 | 2.78 |

| GO:0044092 | Negative regulation of molecular function | 9.6 × 10−3 | 2.56 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 4 | |||

| GO:0031145 | Anaphase-promoting complex-dependent proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 1.8 × 10−4 | 7.24 |

| GO:0010498 | Proteasomal protein catabolic process | 4.4 × 10−3 | 4.62 |

| GO:0043161 | Proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process | 4.4 × 10−3 | 4.62 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 5 | |||

| GO:0031397 | Negative regulation of protein ubiquitination | 4.1 × 10−4 | 6.36 |

| GO:0031400 | Negative regulation of protein modification process | 9.2 × 10−4 | 4.68 |

| GO:0031398 | Positive regulation of protein ubiquitination | 1.0 × 10−3 | 5.61 |

| GO:0032269 | Negative regulation of cellular protein metabolic process | 3.2 × 10−3 | 3.58 |

| GO:0031396 | Regulation of protein ubiquitination | 4.2 × 10−3 | 4.71 |

| GO:0051248 | Negative regulation of protein metabolic process | 4.4 × 10−3 | 3.43 |

| GO:0031401 | Positive regulation of protein modification process | 4.1 × 10−2 | 2.98 |

| GO:0032268 | Regulation of cellular protein metabolic process | 4.7 × 10−2 | 2.08 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 6 | |||

| GO:0065003 | Macromolecular complex assembly | 1.4 × 10−8 | 2.96 |

| GO:0043933 | Macromolecular complex subunit organization | 9.9 × 10−8 | 2.77 |

| GO:0034622 | Cellular macromolecular complex assembly | 3.2 × 10−6 | 3.63 |

| GO:0034621 | Cellular macromolecular complex subunit organization | 2.6 × 10−5 | 3.24 |

| GO:0065004 | Protein-DNA complex assembly | 1.1 × 10−4 | 6.12 |

| GO:0034728 | Nucleosome organization | 5.2 × 10−4 | 5.52 |

| GO:0006461 | Protein complex assembly | 2.1 × 10−3 | 2.37 |

| GO:0070271 | Protein complex biogenesis | 2.1 × 10−3 | 2.37 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 7 | |||

| GO:0006334 | Nucleosome assembly | 2.4 × 10−4 | 6.12 |

| GO:0031497 | Chromatin assembly | 3.1 × 10−4 | 5.90 |

| GO:0006323 | DNA packaging | 8.2 × 10−4 | 4.76 |

| GO:0006333 | Chromatin assembly or disassembly | 6.0 × 10−3 | 4.04 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 8 | |||

| GO:0008380 | RNA splicing | 5.6 × 10−6 | 3.77 |

| GO:0006396 | RNA processing | 5.7 × 10−6 | 2.82 |

| GO:0006397 | mRNA processing | 1.5 × 10−4 | 3.20 |

| GO:0000398 | Nuclear mRNA splicing, via spliceosome | 2.0 × 10−4 | 4.48 |

| GO:0000377 | RNA splicing, via transesterification reactions with bulged adenosine as nucleophile | 2.0 × 10−4 | 4.48 |

| GO:0000375 | RNA splicing, via transesterification reactions | 2.0 × 10−4 | 4.48 |

| GO:0016071 | mRNA metabolic process | 8.5 × 10−4 | 2.78 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 9 | |||

| GO:0006412 | Translation | 2.6 × 10−8 | 4.01 |

| GO:0006414 | Translational elongation | 5.4 × 10−5 | 5.93 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 10 | |||

| GO:0006367 | Transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 1.1 × 10−3 | 6.30 |

| GO:0006352 | Transcription initiation | 4.5 × 10−3 | 5.16 |

|

| |||

| Cluster 11 | |||

| GO:0006368 | RNA elongation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 1.1 × 10−3 | 7.13 |

| GO:0006354 | RNA elongation | 4.5 × 10−3 | 6.71 |

3.2. Mitochondrial Related Genes in RTT Patients

Among these clusters, the most significantly regulated transcripts include those encoding several subunits of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes and thus linked directly to mitochondrial ATP production and, indirectly, to potential reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In particular, NDUFA1, NDUFAB1, NDUFA2, and NDUFB6, all components of mitochondrial complex I (NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase), showed the greater changes with a FC of more than 2. Moreover, other subunits of complex I (NDUFV2, NDUFS4, NDUFA9, NDUFS6, NDUFB10, NDUFB4, NDUFC2, NDUFB2, NDUFS5, NDUFC1, NDUFB9, and NDUFA8) were clearly upregulated in RTT group.

Complex I plays a vital role in cellular ATP production, the primary source of energy for many crucial processes in living cells. It removes electrons from NADH and passes them by a series of different protein coupled redox centers to the electron acceptor ubiquinone. Because complex I is central to energy production in the cell, it is reported that its malfunction results in a wide range of neuromuscular diseases [25]. Some of them are due to mutations in the mitochondrial genome, but others, which result from a decrease in the activity of complex I or an increase in the production of ROS, are not well understood. The production of ROS by complex I is linked to Parkinson's disease and to ageing [26, 27] and this is in line with RTT since it is now well documented as an increased OS condition in this pathology [22, 23].

Another gene involved in complex I function is NDUFV2 that was also clearly upregulated in our study. Mutations in this gene are implicated in Parkinson's disease, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia and have been found in one case of early onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and encephalopathy; also it has been shown for NDUFA2, a subunit of the hydrophobic protein fraction of the complex I. Mutations in this gene are associated with Leigh syndrome, an early onset progressive neurodegenerative disorder. Of note is NDUFAB1, which is a carrier of the growing fatty acid chain in fatty acid biosynthesis in mitochondria and alteration in fatty acid levels has been noted in ASD [28, 29].

Not only complex I subunits were upregulated in RTT, but also we have detected an upregulation of genes involved in all the five complexes of the electron transport chain. In fact, also SDHB (succinate dehydrogenase complex, subunit B, and iron sulfur (Ip)) gene encoding for a subunit of mitochondrial complex II (succinate: ubiquinone oxidoreductase) was significantly upregulated. This subunit is responsible for transferring electrons from succinate to ubiquinone (coenzyme Q). Complex II of the respiratory chain, which is specifically involved in the oxidation of succinate, carries electrons from FADH to CoQ. Of note, also 3 genes, UQCRQ, UQCRFS1, and UQCRH, encoding for subunits of complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase), were upregulated with a mean FC = 1.60. This complex plays a critical role in biochemical generation of ATP, contributing to the generation of electrochemical potential by catalyzing the electron transfer reaction from ubiquinol to cytochrome c coupled with proton translocation across the membrane. Lines of evidence report that in mouse models some of the promoters of ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase subunit are able to be targeted by MECP2 protein, contributing to the development of the pathology [30].

Furthermore, the cytochrome c gene (CYCS) together with genes encoding subunits of mitochondrial complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) (COX14, COX7A2, COX6C, COX7C, and COX8A) was upregulated with a mean FC of circa 1.5. Of note is the upregulation of cytochrome c gene. The encoded protein accepts electrons from cytochrome b and transfers them to the cytochrome oxidase complex. This protein is also involved in initiation of apoptosis and this would be in line with previous studies that have shown a possible involvement of apoptosis in RTT [31, 32], although only few studies have investigated the role of apoptosis in RTT and the current literature is still controversial. In addition, several subunits of complex IV were upregulated. It receives an electron from each of the four cytochrome c molecules and transfers them to one oxygen molecule, converting molecular oxygen to two molecules of water. In the process, via a protons translocation, it is able to generate ATP. This data would suggest that RTT patients are in continuous new ATP synthesis and this could be a consequence of new protein synthesis.

Our data are in line with a previous work by Kriaucionis where the authors have analyzed the gene profile in the brain of RTT animal model [30]. They have shown that there were several mitochondrial abnormalities and an upregulation of both complexes I and III subunits. In particular they were also able to show a correlation between upregulation of complexes I and III and the animal symptoms severity with a significant increase in mitochondrial respiratory capacity and a reduction in respiratory efficiency. The defect appears to be associated with respiratory complex III, which is also upregulated in our study, and that containing the Uqcrc1 protein. In addition it has been shown that MeCP2 binds to the promoter of the Uqcr gene in vivo and that Uqcr mRNA expression is elevated in brains of Mecp2-null mice that have acquired neurological symptoms and this is in line with our results.

Finally, we also observed in RTT PBMC an upregulation of mitochondrial complex V (ATP synthase) subunits (ATP5A1, ATP5EP2, ATP5J2, and ATP5O) together with ATPase inhibitory factor 1 gene (ATPIF1). Mitochondrial membrane ATP synthase is a master regulator of energy metabolism and cell fate; therefore, a misregulation of this gene can be associated with altered ATP production and cell metabolism. It is interesting to note that also the ATPase inhibitory factor 1 (ATPIF1) that inhibits the activity of the mitochondrial H+-ATP synthase was upregulated, and this lets us speculate the existence of an aberrant loop between making new ATP and inhibiting its production. In addition, recent findings indicate that ATPIF1 has additional functions by promoting adaptive responses of cell to ROS [33], a condition (OS) that has been well documented to be present in RTT [22, 23].

Similarly, other genes related to the ATP synthesis showed significant expression changes (i.e., CYB5A, CYB561D2, ETFA, LDHB, PDHB, and SURF1). For instance, ETFA (electron transfer flavoprotein, alpha polypeptide) serves as a specific electron acceptor for several dehydrogenases and in mitochondria it shuttles electrons between primary flavoprotein dehydrogenases and the membrane-bound electron transfer flavoprotein ubiquinone oxidoreductase. In addition, LDHB encodes lactate dehydrogenase B, an enzyme that catalyzes the reversible conversion of lactate and pyruvate and NAD and NADH, in the glycolytic pathway, being therefore correlated with ATP generation. Of note is the upregulation of SURF1 (surfeit 1) gene that encodes a protein localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane and thought to be involved in the biogenesis of the cytochrome c oxidase complex.

Related to mitochondrial structure/organization, we found upregulation of 7 translocase genes (TIMM10, TSPO, TIMM9, TIMM17A, TOMM7, TIMM13, and TIMM8B) involved in proteins import into mitochondrion (mean FC of 1.34) and of several mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPL13, MRPL20, MRPL21, MRPL33, MRPL51, MRPL52, MRPS25, MRPS30, MRPS33, MRPS36, RPL10A, RPL13, RPL15, RPL22, RPL22L1, RPL26, RPL31, RPL32, RPL39L, RPS10, RPS25, RPS26, RPS26P11, RPS29, RPS5, and RPS7) with a mean FC of 1.5.

All together these lines of evidence seem to suggest an increased mitochondrial activity that might be linked to the observation of the pathologic phenotype. Anyways at this stage of the study, it is not possible to determine whether or not there is an increase in ATP levels. It is possible to speculate that increased genes related to mitochondrial subunits could be a consequence of increased cells request of energy (ATP). This hypothesis is in line with recent study where the authors have shown decreased levels of ATP in brain mouse RTT [34].

Recent discussions regarding a possible connection between RTT and mitochondrial dysfunction have generated significant interest. The basis for these discussions is related in part to the common features of RTT on the one hand and disorders of mitochondrial function on the other. Of interest is the fact that a patient with symptoms normally associated with mitochondrial disorders harbored mutations in the MeCP2 gene [35]. This overlap between symptoms of RTT and mitochondrial disorders recalls early reports of structural abnormalities [36, 37] and defects in the electron transport chain [37, 38] in mitochondria from skin and muscle biopsies of RTT patients. Moreover, about half of RTT patients were reported to have elevated levels of circulatory lactic or pyruvic acid, which might be caused by defects in the efficiency of the respiratory chain and urea cycle complexes, both of which are mitochondrial [39–41]. Several disorders related to the brain are a consequence of mitochondrial alteration with the resultant increase of OS and in certain cases the cell apoptosis. As RTT is not a neurodegenerative disorder [42], any contribution of mitochondrial dysfunction to RTT symptoms may take the form of chronic mitochondrial underperformance, rather than catastrophic failure leading to neuronal death.

To date, no systematic study of mitochondrial function in individuals with RTT has presented whether these findings represent a primary or secondary effect; that is, are they involved directly in the clinical features of RTT or do they reflect effects of these clinical features on mitochondrial function? Prior to identification of mutations in MeCP2 in 1999, several reports appeared to be related to mitochondrial structure and function [36–54]. However, since 2001, publications on a possible role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of RTT have been very few [36, 54]. In a recent work, investigators in Australia reported gene expression results from postmortem brain tissue of individuals with RTT and normal controls [55]. One gene related to a mitochondrial enzyme, cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1, had reduced expression in RTT tissue raising the possibility that loss of MeCP2 function could be responsible. However, whether this is a primary or secondary finding remains to be established and provides an important target for further investigation.

In summary, while mitochondrial abnormalities related to structure and functions have been reported, sufficient information is lacking as to the precise role of such abnormalities in RTT. As mentioned, alteration of mitochondrial functions is often correlated with OS and, in particular, the mitochondrial sites that are often invoked as the most important mitochondrial superoxide producers are in respiratory complexes I and III [56, 57] and this can explain the increased OS levels found in RTT patients.

3.3. Oxidative Stress Related Genes in RTT Patients

The presence of a redox unbalance in RTT is confirmed by the upregulations of several genes involved in redox homeostasis such as superoxide dismutase 1, catalase, and peroxiredoxin 1 (SOD1, CAT, and PRDX1) with a 1.6, 1.14, and 1.12 FC, respectively. Moreover, glutathione S-transferase omega 1, microsomal glutathione S-transferase 2, and microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 (GSTO1, MGST2, and MGST3) are also overexpressed in RTT with a FC = 2.1. For instance, SOD1 upregulation could be a consequence of increased superoxide production by aberrant activation of complex I and III and the dismutation of superoxide in H2O2 can explain the increased expression of CAT and PRDX1. It is likely to believe that the compensatory antioxidant system is not quite sufficient to quench ROS production and this could explain the high OS level present in RTT [22, 23]. For this reason the induction of glutathione S-transferase omega-1 (GSTO1) is not surprising. This enzyme is involved in the detoxification mechanisms via conjugation of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidativelly modified proteins (carbonyls and 4-HNE PAs). In fact, the GST genes are upregulated in response to OS. In addition, our results showed the upregulation of MGST2 and MGST3 which are the microsomal glutathione S-transferases; this data correlates very well with our previous findings where RTT patients showed an increased level of 4-HNE PAs, as MGST2 is able to also conjugate 4-HNE with GSH [58]. We also observed an increased expression of mRNA for alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (ADH5), aldo-keto reductase family 1, member A1 (AKR1A1) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A1 (ALDH1A1), all enzymes involved in lipid peroxidation products detoxification [59].

3.4. Ubiquitin-Proteasome Related Genes in RTT Patients

Our results evidenced also the upregulation of genes related to protein degradation and ubiquitination. In fact, RTT PBMC microarray data revealed increased expression levels of genes associated with protein turnover, such as genes encoding proteasome subunits (PSMA2, PSMA3, PSMA5, PSMA7, PSMB1, PSMB10, PSMC5, PSMC6, PSMD6, and PSMD9); furthermore, proteasome maturation protein (POMP), involved in proteasome assembly, and genes regulating the activity of the ubiquity ligases (RBX1, UFC1, CCNB1IP1, and DAXX) are also up regulated (Table 2), suggesting an increase in cell and protein degradation processes. This could also be a consequence of oxidized proteins and the presence of 4-HNE PAs. This evidence is supported by the observed upregulation of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E3 (UBE2E3, FC = 1.19) that accepts ubiquitin from the E1 complex and catalyzes its covalent attachment to other proteins. However, this is in contrast with some lines of evidence that link RTT to the downregulation of ubiquitin conjugating enzymes (UBE3A) by MeCP2 [60]. Overall the effect of MeCP2 on UBE3A regulation is still controversial. In fact, there is even a recent work that did not find any difference in UBE3A expression between wild type and a RTT mouse with the mutation R168X [61]. In general, the levels of protein ubiquitination, that is one of the steps to degrade modified proteins, are increased in RTT [24].

3.5. Chromatin Folding Related Genes in RTT Patients

In addition several histone related genes (HIST1H1B, HIST1H2AB, HIST1H2AI, HIST1H2AJ, HIST1H2AL, HIST1H2BB, HIST1H2BH, HIST1H2BM, HIST1H3B, HIST1H3F, HIST1H3I, HIST1H3J, HIST1H4D, HIST1H4F, and HIST1H4) were downregulated with a mean FC of −1.28 suggesting a reduced production of proteins necessary to the DNA chromatin assembly.

In general, histone modifications are very dynamic and include acetylation, methylation, isomerization, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination [62]. The combination of such modifications confers enormous variability of cellular signals to environmental stimuli. It is easy to understand that modifications such as histone methylation can display additional complexity since the degree of methylation is very variable (mono-, di-, or trimethylation) [63]. Furthermore, combinations or sequential additions of different histone marks can affect the chromatin organization and subsequently alter the expression of the corresponding target genes.

In our case, several genes related to histone expression were downregulated and this can dramatically affect gene expression. For instance, histone H1 protein binds to linker DNA between nucleosomes forming the macromolecular structure known as the chromatin fiber. Histones H1 are necessary for the condensation of nucleosome chains into higher-order structured fibers. Acts also as a regulator of individual gene transcription through chromatin remodeling, nucleosome spacing, and DNA methylation. We have detected a down-regulation of several H1 subunits ranging from 2- to 3-fold in RTT patients.

3.6. Validation of Selected PBMC mRNAs by qPCR Analyses

Next, we wanted to confirm the differential expression observed for selected mRNAs, on an individual basis, by RT-qPCR. Six genes were selected based on their different patterns of expression (3 up- and 3 downregulated). Assessment of their mRNA expression levels by RT-qPCR accurately reflected those obtained by microarray profiling (Figure 2), thereby confirming the validity of our microarray results. The levels of three mRNAs encoding for glutathione S-transferase omega 1 (GSTO1), proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type-10 (PSMB10), and cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIIIA (COX8A) were upregulated in RTT patients by 2.5-, 2- and 2.2-fold, respectively (Figure 2), very similarly to the levels measured by gene array. In contrast, histone cluster 1, H1b (HIST1H1B), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9), and Rho GTPase activating protein 11B (ARHGAP11B) were downregulated by ∼50% in RTT patients, as compared to healthy subjects (Figure 2) and also in this case similar expression was detected by gene array analysis.

Figure 2.

Validation of relative gene expression levels for selected genes using RT-qPCRin PBMC from 12 RTT patients and 7 controls. Results are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments, each analysed in triplicate. *P value < 0.001 versus control (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-test).

3.7. Conclusion

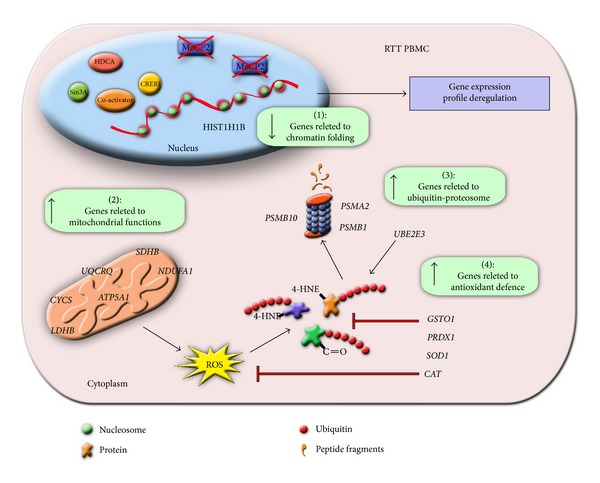

Our microarray data reveal an altered gene expression profile in RTT lymphomonocytes with the upregulation of genes related to mitochondrial biology and ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. In particular, the overexpression of the genes involved in ATP synthesis processes means the tendency of cells to show an altered energy requirement, perhaps to cope with the increased activities of protein degradation. On the other hand, it should be noted that mitochondrion plays essential roles in mediating the production of ROS and these in turn cause damage to proteins, as well as lipids and nucleic acids. To remove damaged molecules, in a kind of vicious circle, increased cellular proteolytic activity requires an extra mitochondrial ATP production with a further ROS generation. This picture is consistent with our previous reports [24], indicating the alteration of redox status in RTT patients, coupled with the increased ubiquitination and degradation of oxidatively modified proteins (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Schematic summary related to the altered gene expression observed in RTT PBMC. MeCP2 in a normal situation binds to several cofactors (Sin3A, CREB1, etc.) to regulate gene transcription. Mutation of MeCP2 (crossed boxes) will affect gene expression leading to a gene profile deregulation. There are mainly 4 gene clusters significantly affected in RTT PBMC, that is, those related to chromatin folding (1), mitochondrial functions (2), ubiquitin-proteasome (3), and antioxidant defence (4) (green boxes). The overexpression of the genes involved in ATP synthesis processes (2) can be interpreted as a possible energy requirement for an increment of cellular protein degradation (3), consequent to increased mitochondrial ROS production and protein oxidation. The increased expression of the “antioxidant cellular defence” genes (4) is the possible compensatory mechanism activated by the cells to quench ROS production and protein oxidation (red arrows).

In conclusion, these findings on transcriptional profiling in RTT patients reveal new molecular mechanisms underlying RTT phenotype, suggesting that mitochondrial-ATP-proteosome are likely to have direct actions on redox balance in RTT syndrome. Furthermore, it confirmed a possible indirect role of OS in pathogenesis and progression of disorder. Thus, RTT should be considered as possible mitochondriopathy.

Supplementary Material

The complete list of differentially expressed genes, both upregulated and downregulated (FC ± 1), is shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank “Fondazione Monte Dei Paschi”, Associazione Italiana Rett (AIRETT) and Tuscany Region (Bando Salute 2009, “Antioxidants (ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, Lipoic Acid) Supplementation in Rett Syndrome: a novel approach to therapy”), for partial support.

References

- 1.Rett A. On a unusual brain atrophy syndrome in hyperammonemia in childhood. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift. 1966;116(37):723–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagberg B. Rett’s syndrome: prevalence and impact on progressive severe mental retardation in girls. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. 1985;74(3):405–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1985.tb10993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurvick CL, de Klerk N, Bower C, et al. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;148(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Annals of Neurology. 2010;68(6):944–950. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neul JL. The relationship of Rett syndrome and MECP2 disorders to autism. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2012;14(3):253–262. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.3/jneul. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bebbington A, Anderson A, Ravine D, et al. Investigating genotype-phenotype relationships in Rett syndrome using an international data set. Neurology. 2008;70(11):868–875. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304752.50773.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neul JL, Fang P, Barrish J, et al. Specific mutations in Methyl-CpG-Binding Protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology. 2008;70(16):1313–1321. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000291011.54508.aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amir RE, Van Den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature Genetics. 1999;23(2):185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY. The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron. 2007;56(3):422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adkins NL, Georgel PT. MeCP2: structure and function. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2011;89(1):1–11. doi: 10.1139/O10-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guy J, Cheval H, Selfridge J, Bird A. The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2011;27:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colantuoni C, Jeon O-H, Hyder K, et al. Gene expression profiling in postmortem Rett Syndrome brain: differential gene expression and patient classification. Neurobiology of Disease. 2001;8(5):847–865. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nectoux J, Fichou Y, Rosas-Vargas H, et al. Cell cloning-based transcriptome analysis in Rett patients: relevance to the pathogenesis of Rett syndrome of new human MeCP2 target genes. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2010;14(7):1962–1974. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traynor J, Agarwal P, Lazzeroni L, Francke U. Gene expression patterns vary in clonal cell cultures from Rett syndrome females with eight different MECP2 mutations. BMC Medical Genetics. 2002;3, article 12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballestar E, Ropero S, Alaminos M, et al. The impact of MECP2 mutations in the expression patterns of Rett syndrome patients. Human Genetics. 2005;116(1-2):91–104. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado IJ, Kim DS, Thatcher KN, LaSalle JM, Van den Veyver IB. Expression profiling of clonal lymphocyte cell cultures from Rett syndrome patients. BMC Medical Genetics. 2006;7, article 61 doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yakabe S, Soejima H, Yatsuki H, et al. MeCP2 knockdown reveals DNA methylation-independent gene repression of target genes in living cells and a bias in the cellular location of target gene products. Genes and Genetic Systems. 2008;83(2):199–208. doi: 10.1266/ggs.83.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasui DH, Xu H, Dunaway KW, Lasalle JM, Jin LW, Maezawa I. MeCP2 modulates gene expression pathways in astrocytes. Molecular Autism. 2013;4(1):p. 3. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis G, Jr., Sherman BT, Hosack DA, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biology. 2003;4(5):p. P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cervellati F, Valacchi G, Lunghi L, et al. 17-β-estradiol counteracts the effects of high frequency electromagnetic fields on trophoblastic connexins and integrins. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2013;2013:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/280850.280850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Felice C, Ciccoli L, Leoncini S, et al. Systemic oxidative stress in classic Rett syndrome. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2009;47(4):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pecorelli A, Ciccoli L, Signorini C, et al. Increased levels of 4HNE-protein plasma adducts in Rett syndrome. Clinical Biochemistry. 2011;44(5-6):368–371. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Pecorelli A. Scavenger receptor B1 post-translational modifications in Rett syndrome. FEBS Letters. 2013;587(14):2199–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iommarini L, Calvaruso MA, Kurelac I, Gasparre G, Porcelli AM. Complex I impairment in mitochondrial diseases and cancer: parallel roads leading to different outcomes. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2013;45(1):47–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stefanatos R, Sanz A. Mitochondrial complex I: a central regulator of the aging process. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(10):1528–1532. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.10.15496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauser DN, Hastings TG. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease and monogenic parkinsonism. Neurobiology of Disease. 2013;51:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das UN. Autism as a disorder of deficiency of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and altered metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nutrition. 2013;29(10):1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clark-Taylor T, Clark-Taylor BE. Is autism a disorder of fatty acid metabolism? Possible dysfunction of mitochondrial β-oxidation by long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Medical Hypotheses. 2004;62(6):970–975. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kriaucionis S, Paterson A, Curtis J, Guy J, MacLeod N, Bird A. Gene expression analysis exposes mitochondrial abnormalities in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2006;26(13):5033–5042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01665-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Battisti C, Formichi P, Tripodi SA, et al. Lymphoblastoid cell lines of Rett syndrome patients exposed to oxidative-stress-induced apoptosis. Brain and Development. 2004;26(6):384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anvret M, Zhang ZP, Hagberg B. Rett syndrome: the bcl-2 gene—a mediator of neurotrophic mechanisms? Neuropediatrics. 1994;25(6):323–324. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1073047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Aragó M, Formentini L, Martínez-Reyes I, et al. Expression, regulation and clinical relevance of the ATPase inhibitory factor 1 in human cancers. Oncogenesis. 2013;2, article e46 doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2013.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saywell V, Viola A, Confort-Gouny S, Le Fur Y, Villard L, Cozzone PJ. Brain magnetic resonance study of Mecp2 deletion effects on anatomy and metabolism. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;340(3):776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heilstedt HA, Shahbazian MD, Lee B. Infantile hypotonia as a presentation of Rett syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2002;111(3):238–242. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruch A, Kurczynski TW, Velasco ME. Mitochondrial alterations in Rett syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 1989;5(5):320–323. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(89)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dotti MT, Manneschi L, Malandrini A, De Stefano N, Caznerale F, Federico A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Rett syndrome. An ultrastructural and biochemical study. Brain and Development. 1993;15(2):103–106. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(93)90045-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coker SB, Melnyk AR. Rett syndrome and mitochondrial enzyme deficiencies. Journal of Child Neurology. 1991;6(2):164–166. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuishi T, Urabe F, Percy AK, et al. Abnormal carbohydrate metabolism in cerebrospinal fluid in Rett syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology. 1994;9(1):26–30. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haas RH, Light M, Rice M, Barshop BA. Oxidative metabolism in Rett syndrome—1. Clinical studies. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26(2):90–94. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Jarallah AA, Salih MAM, Al Nasser MN, Al Zamil FA, Al Gethmi J. Rett syndrome in Saudi Arabia: report of six patients. Annals of Tropical Paediatrics. 1996;16(4):347–352. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1996.11747849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong DD. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2002;8(2):72–76. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eeg-Olofsson O, Al-Zuhair AGH, Teebi AS, Al-Essa MMN. Abnormal mitochondria in the Rett syndrome. Brain and Development. 1988;10(4):260–262. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(88)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eeg-Olofsson O, Al-Zuhair AGH, Teebi AS, Al-Essa MMN. Rett syndrome: genetic clues based on mitochondrial changes in muscle. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1989;32(1):142–144. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320320131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eeg-Olofsson O, Al-Zuhair AGH, Teebi AS, et al. Rett syndrome: a mitochondrial disease? Journal of Child Neurology. 1990;5(3):210–214. doi: 10.1177/088307389000500311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wakai S, Kameda K, Ishikawa Y, et al. Rett syndrome: findings suggesting axonopathy and mitochondrial abnormalities. Pediatric Neurology. 1990;6(5):339–343. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(90)90028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mak S-C, Chi C-S, Chen C-H, Shian W-J. Abnormal mitochondria in Rett syndrome: one case report. Chinese Medical Journal. 1993;52(2):116–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornford ME, Philippart M, Jacobs B, Scheibel AB, Vinters HV. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome: case report with neuronal and mitochondrial abnormalities in the brain. Journal of Child Neurology. 1994;9(4):424–431. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naidu S, Hyman S, Harris EL, Narayanan V, Johns D, Castora F. Rett syndrome studies of natural history and search for a genetic marker. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26(2):63–66. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang J, Qi Y, Bao X-H, Wu X-R. Mutational analysis of mitochondrial DNA of children with Rett syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 1997;17(4):327–330. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellaway C, Christodoulou J. Rett syndrome: clinical update and review of recent genetic advances. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1999;35(5):419–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.355403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oi Y, Wu X, Tang J, Bao X. Computerized ribosomal RNA secondary structure modeling of mutants found in Rett syndrome patients and their mothers. Chinese Journal of Medical Genetics. 1999;16(3):153–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Armstrong J, Pineda M, Monrós E. Mutation analysis of 16S rRNA in patients with rett syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 2000;23(1):85–87. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(00)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng H, Pan H, Qi Y. Role of mitochondrial lesion in pathogenesis of sporadic rett syndrome. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 2001;81(11):662–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibson JH, Slobedman B, KN H, et al. Downstream targets of methyl CpG binding protein 2 and their abnormal expression in the frontal cortex of the human Rett syndrome brain. BMC Neuroscience. 2010;11, article 53 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Experimental Gerontology. 2010;45(7-8):466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dröse S, Brandt U. Molecular mechanisms of superoxide production by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2012;748:145–169. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3573-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahmad S, Niegowski D, Wetterholm A, Haeggström JZ, Morgenstern R, Rinaldo-Matthis A. Catalytic characterization of human microsomal glutathione s-transferase 2: identification of rate-limiting steps. Biochemistry. 2013;52(10):1755–1764. doi: 10.1021/bi3014104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poli G, Schaur RJ, Siems WG, Leonarduzzi G. 4-Hydroxynonenal: a membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2008;28(4):569–631. doi: 10.1002/med.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Makedonski K, Abuhatzira L, Kaufman Y, Razin A, Shemer R. MeCP2 deficiency in Rett syndrome causes epigenetic aberrations at the PWS/AS imprinting center that affects UBE3A expression. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(8):1049–1058. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lawson-Yuen A, Liu D, Han L, et al. Ube3a mRNA and protein expression are not decreased in Mecp2R168X mutant mice. Brain Research. 2007;1180(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delcuve GP, Rastegar M, Davie JR. Epigenetic control. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2009;219(2):243–250. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rice JC, Allis CD. Histone methylation versus histone acetylation: new insights into epigenetic regulation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2001;13(3):263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The complete list of differentially expressed genes, both upregulated and downregulated (FC ± 1), is shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.