Abstract

Activation of PPAR-γ through the administration of glitazones has shown promise in preserving function following cardiac injury, although recent evidence has suggested their use may be contraindicated in the case of severe heart failure. This study tested the hypothesis that PPAR-γ expression increases in a time dependent manner in response to chronic volume overload (VO) induced heart failure. Additionally, we attempted to determine what effect 4 week administration of Urotensin II (UTII) may have on PPAR-γ expression. VO induced heart failure was produced in Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 32) by aorta-caval fistula. Animals were sacrificed at 1, 4, and 14 weeks following shunt creation. In a separate set of experiments, animals were administered 300 pmol/kg/h of UTII for 4 weeks, subjected to 4 weeks of volume overload, or given UTII + VO. Densitometric analysis of left ventricular (LV) protein demonstrated PPAR-γ expression was significantly (*p < 0.05) upregulated at 4 and 14 weeks (31.5% and 37%, respectively) post-fistula formation compared to control values. PPAR-γ activation was decreased in the 4 and 14 week (39.16% and 42.4%, respectively), but not in the 1-week animals, and these changes did not correlate with NF-κB activity. Animals given UTII either with or without VO demonstrated increased expression of PPAR-γ as did animals subjected to 4 week VO alone. Animals given UTII either with or without VO had decreased activity vs. control. These data suggest PPAR-γ may play a role in the progression of heart failure, however, the exact nature has yet to be determined.

Keywords: Urotensin II infusion, PPAR-γ activity, NF-κB, Progressive heart failure

1. Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator proteins belong to a nuclear receptor super family of which there are currently three major isoforms; α, β/δ, and γ. In regards to PPAR-γ, previous work has concentrated on its effect on insulin resistance, obesity, and adipocyte differentiation [14]. However, recent evidence has suggested that activation of PPAR-γ results in positive outcomes following cardiovascular insult including decreased left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy [29], remodeling [18,25], and increased cardiac performance [23]. These positive events are also present in patients with congestive heart failure. Additionally, the use of glitazones, agents which activate PPAR-γ, are tolerated in all but late stage patients, presumably due to increased fluid retention [16]. It is currently unclear however, how the expression of PPAR-γ as well as its activity is altered with the progression of disease, though recent data has suggested that in human auricular tissue PPAR-γ mRNA and protein expression is increased in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy [9].

UTII is a cyclic peptide recently associated with a plethora of cardiovascular disease states and appears to be only activated in the presence of disease. Douglas et al. found that end-stage heart failure patients exhibited greater expression of UTII and UTR regardless of the underlying etiology of the heart failure [6]. Additionally, the researchers found that plasma UTII levels inversely correlated with ejection fraction in these patients, suggesting the activated UTII system may depress cardiac contractility. The current data, however, is inconclusive in this regard. Russell et al. found that UTII administration to isolated cardiac strips resulted in an increased force of contraction in both the atria and right ventricle, though no changes were found in the left ventricle [20]. However, Ames et al. discovered in anesthetized primates that low dose (<30 pmol/kg) administration of UTII resulted in increased cardiac output while high dose UTII (>30 pmol/kg) resulted in cardiovascular collapse due to decreased stroke volume with little change in heart rate [2]. Finally, the UTII system has been implicated in adverse remodeling and left ventricular hypertrophy as shown by increased collagen mRNA and protein expression as well as increase leucine incorporation in cell culture [12,26].

Since the current literature suggests antagonistic roles for PPAR-γ and UTII/UTR in regards to remodeling, hypertrophy, and contractility, the main purpose of this study was two-fold: first, to determine the changes in PPAR-γ expression and activity as the severity of heart failure progresses. Second, to determine the effect of chronic administration of UTII on the expression of PPAR-γ.

However, there is no literature showing a link between the UTII and PPAR-γ expression and this is the first study that demonstrates alterations in the expression of PPAR-γ in the chronic UTII administration and VO model of progressive heart failure. In our previous in vitro studies we demonstrated that treatment with PPAR-γ agonists resulted in the reduction of NF-κB activity in cardiac myofibroblasts isolated from the site of myocardial infarction [4]. The current study demonstrates increases in the PPAR-γ expression in these models. Furthermore, we investigated the activity of NF-κB in these tissues in order to understand any possible link it might have to PPAR-γ activity in this model of progressive heart failure.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g were used in this study, and all procedures were approved by the East Carolina University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To study time dependant characteristics of PPAR-γ expression with progressive VO, one cohort of VO animals was divided into groups sacrificed at 1, 4, and 14 weeks post-fistula and compared to respective sham-operated controls. A second cohort of animals was divided into the following groups to study the interaction between UTII and progressive VO: UTII only (UT), volume overload only (VO), and UTII + volume overload (UT + VO). hUTII (American Peptide) administration was begun using subcutaneous Alzet mini-osmotic pumps. Infusions were maintained for 4 weeks in all groups at an estimated delivery of 300 pmol/kg/h. Control animals were infused with saline. After sacrifice, hearts from all animals were frozen and stored at –80 °C.

2.2. Aorto-caval shunt formation

Creation of the aorto-caval shunt was performed as described previously by us [11], which was adopted from Garcia and Diebold [8]. Briefly, a midline abdominal incision was made and the small bowel was displaced using saline soaked gauze. The distal segments of the aorta and vena cava, between the renal arteries and the iliac bifurcation, were visualized and dissected free. Aortic blood flow was occluded and using an 18 gauge needle, the aorta was punctured and the needle was passed into the adjacent vena cava. This was held for 60 s, after which the needle was removed and the puncture site was closed with 3M© Vetbond. Blood flow was restored and the abdominal wall was closed. Successful shunt formation was determined by the presence of bright red pulsatile flow in the distal vena cava. Animals received 1 mL bolus injection of saline into the abdominal space to rehydrate them from possible blood loss. Sham animals were subjected to the same procedure with the exception of puncture of the aorta/vena cava.

2.3. Ventricular pressure measurements

All ventricular measurements were performed under anesthesia. Arterial and left ventricular pressure measurements were made using a fluid filled catheter connected to a pressure transducer and recorded digitally using Grass Polyview software. The right carotid artery was exposed and canulated with PE 40 tubing. The animal then was rotated on its left side and the catheter was advanced. We confirmed entry into the left ventricle via visualization of diastolic pressure measurements of approximately 0 mmHg. After LV pressures were recorded, the catheter was withdrawn back into the aorta for arterial pressure measurements.

2.4. Western blot

Left ventricular protein (20–25 mg of tissue) was extracted in 1 mL of RIPA with 0.01% Triton X 100 to measure changes in the expression of PPAR-γ. Protein samples (20 μg) were electrophoresed on 4–12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked with TBS-T containing 5% non-fat milk overnight at 4 8C. Membranes were incubated with PPAR-γ antisera for 4 h at a concentration of 1:5000. Horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antisera at 1:5000. Protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence detection system (ECL Amersham).

2.5. PPAR-γ and NF-κB DNA binding assays

PPAR-γ and NF-κB binding assay kits were purchased from Panomics (Fremont, CA) and performed based on their protocol. Briefly, left ventricular homogenates (25 μg) were incubated with DNA oligos to form protein (PPAR-γ or NF-κB)/DNA complexes. These complexes were then transferred to a separate reaction assay plate incubated for 1 h to capture the protein/DNA complexes. The specific primary antibody was incubated for 1 h followed by a series of washes and finally the secondary antibody for 1 h. Substrate solution was then added to the assay plate for ~10 min and monitored for color development. The reaction was stopped with stop solution and read at an absorbance of 450 nm.

2.6. Statistics

Values were reported as means ± S.E.M., n = 8 in each group. Differences between groups were compared using ANOVA with Fishers test for least significant difference. In all cases a p value of ≤0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance between groups.

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of morphometric and cardiac function in chronic administration of UTII and VO models of heart failure

We used previously described VO and Chronic administration of UTII models of progressive heart failure [11]. In this study, we investigated the link between the UTII, progressive heart failure and expression of PPAR-γ. These models displayed similar to previously published morphologic, hemodynamic and functional changes in chronic UTII administration and prolonged VO heart failure [11]. Briefly, animals receiving UTII alone displayed significant decreases in cardiac performance by exhibiting increased end diastolic pressure and impaired ±dP/dt compared to control. These changes were not associated with an increase in cardiac hypertrophy as measured by the total heart weight, left ventricular weight, or LV weight to body weight ratio. Animals subjected to volume overload alone demonstrated decreased ±dP/dt and increased left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP). Animals subjected to overload in addition to chronic hUTII administration exhibited increased cardiac performance compared to those animals subjected to overload alone as demonstrated by decreased LVEDP and increased ±dP/dt compared to VO alone.

3.2. PPAR-γ expression increases with severity of heart failure

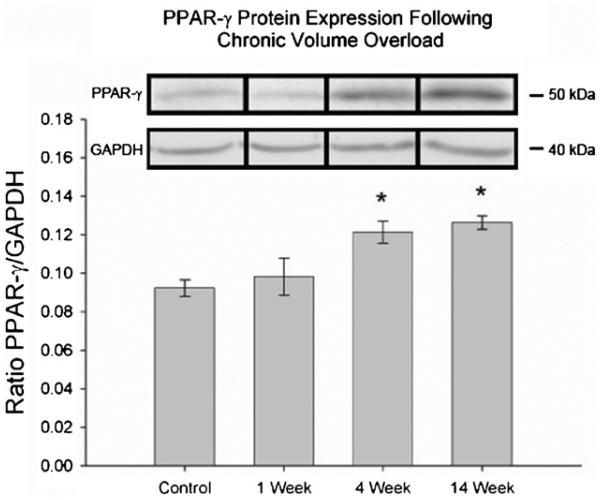

Following prolonged exposure to volume overload, PPAR-γ expression was significantly increased (*p < 0.05) at 4 and 14 weeks following volume overload compared to control animals (Fig. 1). Animals in the 1 week group did not have a significant increase in PPAR-γ expression.

Fig. 1.

PPAR-γ protein expression by Western blot in heart tissues following 1, 4, and 14 week volume overload. *p < 0.002 vs. control.

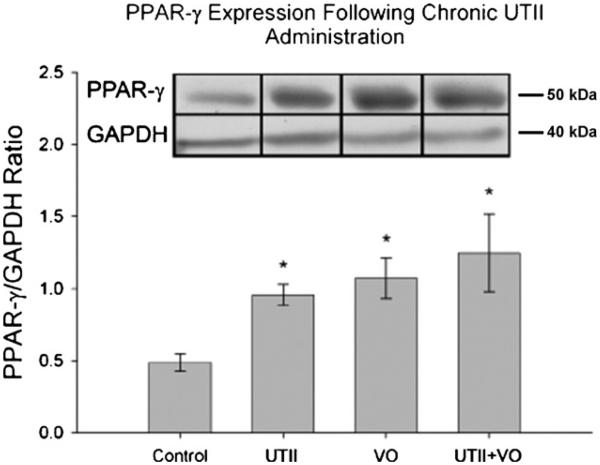

3.3. PPAR-γ expression is influenced by Urotensin II (UTII)

UTII has been shown in various models to increase hypertrophy and collagen deposition while activated PPAR-γ has been shown to perform the opposite. We therefore wanted to determine if UTII influenced PPAR-γ expression since we have shown UTII and its receptor are increased in this model [11]. As shown in Fig. 2, PPAR-γ expression was significantly increased in response to UTII alone (0.95 ± 0.07), 4 week VO (1.07 ± 0.14), and VO + UTII (1.25 ± 0.27) when compared to control (0.48 ± 0.06).

Fig. 2.

PPAR-γ expression by Western blot in heart tissues in UTII, VO, and UTII + VO animals. UTII—animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII; VO—animals subjected to 4 weeks volume overload; UTII + VO—Animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII + 4 weeks VO.*p < 0.05 vs. control.

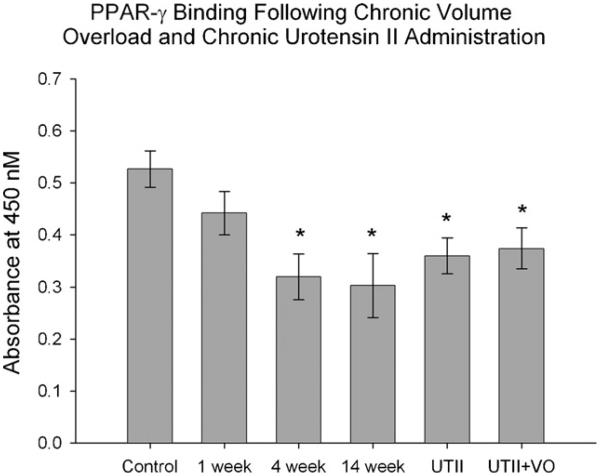

3.4. PPAR-γ DNA binding activity is decreased as heart failure progresses

The PPAR-γ binding activity may be independent of protein expression; hence we used a commercially available assay to determine PPAR-γ activity. Interestingly, the PPAR-γ activity was significantly decreased (*p < 0.05) in the 4 and 14 week animals (4 week: 0.32 ± 0.04, 14 week: 0.30 ± 0.06 vs. Control: 0.52 ± 0.03), but not in 1 week. Similarly, the PPAR-γ activity in animals receiving chronic UTII was significantly decreased (*p < 0.05) compared to control animals (UTII alone: 0.36 ± 0.03, UTII + VO: 0.37 ± 0.03) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PPAR-γ activity in heart tissues of animals subjected to progressive VO (lanes 2–4; 1, 4 and 14 weeks, respectively) and/or UTII (lane 5). UTII—animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII; VO—animals subjected to 4 weeks volume overload (lane 3); UTII + VO—animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII + 4 weeks VO (lane 6). *p < 0.05 vs. control.

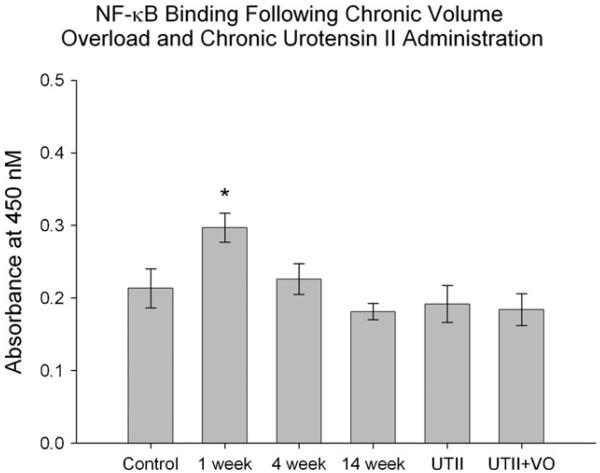

3.5. NF-κB binding activity is increased early in heart failure

It is important to understand the link between PPAR-γ and NF-κB activities in progressive heat failure. Therefore, we measured NF-κB activity following volume overload and UTII administration. Animals in the 1 week group had significantly increased NF-κB activity (*p < 0.05) compared to all other groups including controls. There were no differences in the remainder of the experimental groups (Fig. 4), suggesting little or no correlation between PPAR-γ expression and NF-κB activity in rest of the experimental groups.

Fig. 4.

NF-κB DNA binding activity in heart tissues of animals subjected to progressive VO (lanes 2-4; 1, 4 and 14 weeks, respectively) and/or UTII. UTII—animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII (lane 5); VO—animals subjected to 4 weeks volume overload (lane 3); UTII + VO—animals subjected to 4 weeks UTII + 4 weeks VO (lane 6). *p < 0.05 vs. control and all other experimental groups.

4. Discussion

Currently, the majority of information regarding PPAR-γ is in relation to its modulation of adipocyte physiology leading to insulin sensitivity [14]. However, a growing body of evidence suggests a possible role for PPAR-γ as a protective regulator in the cardiovascular system, particularly by decreasing hypertrophy, remodeling, and infarct size [21,24,28,29]. Conversely, UTII has been shown to behave in an opposing fashion. In the present study, we found that PPAR-γ expression increases in animals subjected to progressive volume overload with a subsequent decrease in PPAR-γ activity. Four weeks of UTII administration resulted in increased expression of PPAR-γ accompanied by decreased activity compared to controls. NF-κB, a potential mediator of inflammatory pathways and PPAR-γ activity, was increased in 1 week animals only. This is the first study using a well-recognized animal model of heart failure to measure changes in PPAR-γ expression and activity. The data presented here, however, follow well with that observed by Gomez-Garre et al. [9]. In their study, the researchers measured PPAR-γ expression in left ventricles of patients with end-stage heart failure due to ischemic cardiomyopathy. They found PPAR-γ mRNA and protein expression was increased in the heart failure group compared to non-failing controls with no increase in PPAR-γ activation in the heart failure group.

The implications for increasing the expression of PPAR-γ in response to cardiovascular insult are clear based on evidence from in vivo and in vitro experiments. Asakawa et al. administered pioglitazone for 4 weeks to PPAR-γ deficient mice (PPAR-γ+/−) subjected to pressure overload via constriction of the abdominal aorta and showed that activation of PPAR-γ in wild type animals resulted in decreased hypertrophy as measured by HW/BW ratios. However, in PPAR-γ+/− mice, banding alone resulted in increased hypertrophy when compared to wild type banded animals, while treatment with pioglitazone reduced the hypertrophy in PPAR-γ deficient mice. This suggests not only a role for PPAR-γ, but also a PPAR-γ independent mechanism for pioglitazone [3]. Using mice which have PPAR-γ knockout specifically in cardiomyocytes, Duan et al. found the absence of PPAR-γ resulted in increased hypertrophy, increased expression of ANP and b-MHC, genes associated with pathological cardiac hypertrophy, and increased activation of NF-κB [7]. Interestingly, the researchers also found that 4 week treatment of these animals with rosiglitazone resulted in an increase in left ventricular weight to body weight, typically a marker of ventricular hypertrophy again suggesting a PPAR-γ independent activity of these pharmacological agents. Increased mechanical stress, such as that demonstrated during volume overload, has been shown to be a mediator of hypertrophy. Yamamoto et al. used neonatal rat ventricular myocytes subjected to cyclic mechanical strain to measure the effects of PPAR-γ activation on myocyte enlargement as well as protein synthesis. The study demonstrated that activation of PPAR-γ resulted in decreased myocyte area, total protein content, incorporation of [3H+]leucine, and NF-κB activation [29].

UTII has been previously implicated in the progression of both heart failure as well as myocyte hypertrophy. The dose of UTII used in this study (300 pmol/kg/h) has been well established to cause alterations in cardiac function. Kompa et al. have demonstrated that 2 week administration of this dose in rats resulted in decreased cardiac performance as measured by maximal positive and negative first derivative of left ventricular pressure ( ±dP/dt), and a decrease in left ventricular end diastolic pressure [13]. The current study utilized chronic administration of UTII to determine what role it may play in the expression and activation of PPAR-γ. Animals subjected to 4 and 14 week volume overload demonstrated decreased PPAR-γ activity. Our lab has shown increased UTII and UTR mRNA expression in response to chronic volume overload [11]. In the present study, we show that PPAR-γ activity is progressively decreased as the severity of heart failure increases. This suggests that the increased expression of UTII/UTR may potentially lead to a decrease in the PPAR-γ activation and further shown in the animals given UTII without VO. It is known that activation of the UTR leads to an increase in PKC [19] and ERK1/2 activation [17], while PPAR-γ activation has been shown to be inhibited by both PKC and ERK1/2 mediated PPAR-γ phosphorylation [5]. This suggests the inhibitory actions of UTII/UTR on PPAR-γ may indeed act by activating PKC and/or ERK1/2, thereby phosphorylating PPAR-γ. Therefore, the increase in PPAR-γ expression may not be a direct effect of UTII, but may be a secondary result of PPAR-γ inactivation. Furthermore, PPAR-γ activity does not correlate with its protein levels, suggesting a possible role for co-activators associated with the activation of PPAR-γ.

In this study, the NF-κB activity was increased only at the 1 week time point, but showed no significant changes at weeks 4 or 14, and UTII with and without VO. Previous research has shown that patients with dilated cardiomyopathy have a progressive decrease in NF-κB activation as left ventricular end diastolic volume increases. The authors suggest that increasing NF-κB activation may help preserve LV function due to decreased apoptosis [1]. Though the animals in the UTII + VO group did exhibit increased cardiac performance [11], this was not due to an increase in NF-κB activation, though UTII itself has been suggested to have an anti-apoptotic effects [22]. The increase in NF-κB may be an early response to the increased mechanical stress induced by the volume overload [15], the increased activation of inflammatory cytokines [27], or a response to hypoxic conditions [10].

In summary, we found the protein expression of PPAR-γ increases with the progression of heart failure. In the presence of UTII, PPAR-γ expression is also increased, though this may be secondary to UTII mediated PPAR-γ inactivation. NF-κB activation was only increased in the 1 week animals, but not at 4 and 14 week. It is still unclear to what extent PPAR-γ is able to modulate hypertrophy in this model, though it is clear further research needs to be performed to elucidate its actions in order to capitalize on its possible therapeutic benefits.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health grant, HL-60047 awarded to L.C.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter P, Rupp H, Maisch B. Activated nuclear transcription factor [kappa]B in patients with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy—relation to inflammation and cardiac function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:180–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames RS, Sarau HM, Chambers JK, Willette RN, Aiyar NV, Romanic AM, et al. Human urotensin-II is a potent vasoconstrictor and agonist for the orphan receptor GPR14. Nature. 1999;401:282–6. doi: 10.1038/45809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asakawa M, Takano H, Nagai T, Uozumi H, Hasegawa H, Kubota N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma plays a critical role in inhibition of cardiac hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 2002;105:1240–6. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chintalgattu V, Harris GS, Akula SM, Katwa LC. PPAR-gamma agonists induce the expression of VEGF and its receptors in cultured cardiac myofibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74(1):140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diradourian C, Girard J, Pegorier JP. Phosphorylation of PPARs: from molecular characterization to physiological relevance. Biochimie. 2005;87:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas SA, Tayara L, Ohlstein EH, Halawa N, Giaid A. Congestive heart failure and expression of myocardial urotensin II. Lancet. 2002;359:1990–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08831-1. 9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Russell MW, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Cardiomyocyte-specific knockout and agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-{gamma} both induce cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circ Res. 2005;97:372–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000179226.34112.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia R, Diebold S. Simple, rapid, and effective method of producing aortocaval shunts in the rat. Cardiovasc Res. 1990;24:430–2. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.5.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomez-Garre D, Herraiz M, Gonzalez-Rubio ML, Bernal R, Aragoncillo P, Carbonell A, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and -gamma in auricular tissue from heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg H, Ye X, Wilson D, Htoo A, Hendersen T, Liu S. Chronic intermittent hypoxia activates nuclear factor-[kappa]B in cardiovascular tissues in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris GS, Lust RM, Katwa LC. Hemodynamic effects of chronic urotensin II administration in animals with and without aorto-caval fistula. Peptides. 2007;28(8):1483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johns DG, Ao Z, Naselsky D, Herold CL, Maniscalco K, Sarov-Blat L, et al. Urotensin-II-mediated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy: effect of receptor antagonism and role of inflammatory mediators. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;370:238–50. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0980-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kompa AR, Thomas WG, See F, Tzanidis A, Hannan RD, Krum H. Cardiovascular role of urotensin II: effect of chronic infusion in the rat. Peptides. 2004;25(10):1783–8. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The Many Faces of PPAR[gamma] Cell. 2005;123:993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang F, Gardner DG. Mechanical strain activates BNP gene transcription through a p38/NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1603–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niemeyer NV, Janney LM. Thiazolidinedione-induced edema. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:924–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.11.924.33626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onan D, Pipolo L, Yang E, Hannan RD, Thomas WG. Urotensin II promotes hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes via mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2344–54. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos P, Bousette N, Giaid A. Urotensin-II and cardiovascular remodeling. Peptides. 2008;29:764–9. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell FD, Molenaar P. Investigation of signaling pathways that mediate the inotropic effect of urotensin-II in human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:673–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell FD, Molenaar P, O’Brien DM. Cardiostimulant effects of urotensin-II in human heart in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakai S, Miyauchi T, Irukayama-Tomobe Y, Ogata T, Goto K, Yamaguchi I. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activators inhibit endothelin-1-related cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103(Suppl. 48):16S–20S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S016S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi L, Ding W, Li D, Wang Z, Jiang H, Zhang J, et al. Proliferation and anti-apoptotic effects of human urotensin II on human endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188(October (2)):260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimoyama M, Ogino K, Tanaka Y, Ikeda T, Hisatome I. Hemodynamic basis for the acute cardiac effects of troglitazone in isolated perfused rat hearts. Diabetes. 1999;48:609–15. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiomi T, Tsutsui H, Hayashidani S, Suematsu N, Ikeuchi M, Wen J, et al. Pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist, attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:3126–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039346.31538.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuji T, Mizushige K, Noma T, Murakami K, Ohmori K, Miyatake A, et al. Pioglitazone improves left ventricular diastolic function and decreases collagen accumulation in prediabetic stage of a type II diabetic rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:868–74. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzanidis A, Hannan RD, Thomas WG, Onan D, Autelitano DJ, See F, et al. Direct actions of urotensin II on the heart: implications for cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2003;93:246–53. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084382.64418.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valen G. Signal transduction through nuclear factor kappa B in ischemia-reperfusion and heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2004;99:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wayman NS, Hattori Y, McDonald MC, Mota-Filipe H, Cuzzocrea S, Pisano B, et al. Ligands of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR-gamma and PPAR-alpha) reduce myocardial infarct size. FASEB J. 2002;16:1027–40. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto K, Ohki R, Lee RT, Ikeda U, Shimada K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} activators inhibit cardiac hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001;104:1670–5. doi: 10.1161/hc4001.097186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]