Abstract

The erythroleukemia-inducing Friend spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) encodes a unique envelope protein, gp55, which interacts with the erythropoietin (Epo) receptor complex, causing proliferation and differentiation of erythroid cells in the absence of Epo. Susceptibility to SFFV-induced erythroleukemia is conferred by the Fv-2 gene, which encodes a short form of the receptor tyrosine kinase Stk/Ron (sf-Stk) only in susceptible strains of mice. We recently demonstrated that sf-Stk becomes activated by forming a strong interaction with SFFV gp55. To examine the biological consequences of activated sf-Stk on erythroid cell growth, we prepared retroviral vectors which express sf-Stk, either in conjunction with gp55 or alone in a constitutively activated mutant form, and tested them for their ability to induce Epo-independent erythroid colonies ex vivo and disease in mice. Our data indicate that both gp55-activated sf-Stk and the constitutively activated mutant of sf-Stk induce erythroid cells from Fv-2-susceptible and Fv-2-resistant (sf-Stk null) mice to form Epo-independent colonies. Mutational analysis of sf-Stk indicated that a functional kinase domain and 8 of its 12 tyrosine residues are required for the induction of Epo-independent colonies. Further studies demonstrated that coexpression of SFFV gp55 with sf-Stk significantly extends the half-life of the kinase. When injected into Fv-2-resistant mice, neither the gp55-activated sf-Stk nor the constitutively activated mutant caused erythroleukemia. Surprisingly, both Fv-2-susceptible and -resistant mice injected with the gp55-sf-Stk vector developed clinical signs not previously associated with SFFV-induced disease. We conclude that sf-Stk, activated by either point mutation or interaction with SFFV gp55, is sufficient to induce Epo-independent erythroid colonies from both Fv-2-susceptible and -resistant mice but is unable to cause erythroleukemia in Fv-2-resistant mice.

The Friend spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) is a highly pathogenic retrovirus that induces erythroleukemia in susceptible strains of mice within weeks of inoculation. The primary pathogenic determinant for this virus is localized to the env gene, which encodes a 55-kDa protein (gp55) that interacts with the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) complex at the cell surface (18). This interaction results in constitutive activation of erythropoietin (Epo) signal transduction pathways, including the Ras/Raf-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Jak/Stat pathways (10, 12, 14).

Susceptibility to SFFV disease is strain specific and dependent on several different host genes. These genes include those that interfere with viral entry and integration as well as the Fv-2 gene, which functions at the level of the erythroid target cell (for a review, see reference 11). The Fv-2 gene was recently identified as encoding the Stk/Ron tyrosine kinase receptor, a member of the c-Met family of receptor tyrosine kinases (17). Susceptibility to SFFV-induced disease is associated with expression of a short form of Stk, termed sf-Stk, that is expressed from an internal promoter within the Stk gene of Fv-2-susceptible (Fv-2ss) mice that is not functional in Fv-2-resistant (Fv-2rr) mice. The resulting protein lacks most of the extracellular domain required for ligand binding but retains the transmembrane and tyrosine kinase sequences.

Recent experiments have demonstrated that sf-Stk plays an important role in SFFV disease, although the function of sf-Stk in erythropoiesis is unclear. Transfer of bone marrow cells containing the sf-Stk gene into Fv-2rr mice resulted in susceptibility to SFFV, and targeted disruption of this locus in susceptible mice led to disease resistance (17). In addition, we have demonstrated that sf-Stk interacts covalently as well as noncovalently with the gp55 protein of SFFV and that this interaction results in constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of sf-Stk (13). The activation of sf-Stk leads to the recruitment of multiple tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins, including Shc, Cbl, and SHIP, in hematopoietic cells coexpressing the EpoR and gp55 (13). Recent experiments demonstrate that exogenous expression of sf-Stk in bone marrow cells from Fv-2rr mice can restore CFU-E formation in response to SFFV infection, an activity that is abolished by mutation of the Grb2 binding site or two tandem tyrosine residues in the kinase domain of sf-Stk (5).

In this study we established a bicistronic expression system in order to examine the biological consequences for erythroid cells both ex vivo and in vivo of sf-Stk activated by interaction with SFFV gp55. We then compared gp55-activated sf-Stk with sf-Stk activated by point mutation. Our studies suggest that expression of activated sf-Stk, even in the absence of SFFV gp55, is sufficient to induce Epo-independent colonies using erythroid cells from both Fv-2-susceptible and -resistant strains of mice but that additional events play a role in the induction of erythroleukemia in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vector construction.

PCR was used to amplify the internal ribosome entry sequence from the pIRES2 vector (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) using primers designed to incorporate a NotI and PstI site at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. This sequence was cloned into the pBluescript SK(+) plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) upstream of the cDNA for sf-Stk, obtained from the pMX-sfStk-IRES-EGFP vector (12) by EcoRI restriction digestion. The NotI/SalI fragment was cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of the pMX-A-FC vector (13) downstream of the gene encoding the envelope sequences from SFFVA-FC to generate the bicistronic vector pMX-gp55-IRES-sfStk.

Bicistronic vectors with tyrosine (Y)-to-phenylalanine (F) substitutions within sf-Stk were generated by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) with the following primers (mutated codons are underlined): Y173F sense, 5′ GGCCACTTTGGTGTTGTCTTCCACGGAGAATATAC 3′; Y177F sense, 5′ TCTACCACGGAGAATTTACAGACGGAGCACAGAA 3′; Y239F sense, 5′ GTGCTGTTGCCCTTTATGCGCCACGGAGACC 3′; Y274F sense, 5′ GCCTGTGGTATGGAGTTCCTGGCAGAGCAG 3′; Y314F sense, 5′ GCGTCCTAGACAAGGAATTCTACAGTGTTCGCCAGC 3′; Y315F sense, 5′ CCTAGACAAGGAATACTTCAGTGTTCGCCAGCATCGC 3′; Y338F sense,5′ GGAGAGCCTGCAGACCTTCAGGTTCACCACC 3′; Y364F sense, 5′ CGGGGTGCTCCACCCTTCCCCCATATCGAT 3′; Y387F sense, 5′ GCCTGCCTCAGCCTGAGTTCTGTCCTGATTCAC 3′; Y393F sense, 5′ GTCCTGATTCACTGTTTCACGTGATGCTTCGATGC 3′; Y429F sense, 5′ GCTTGGGGACCACTTTGTGCAGCTGACAG 3′; Y436F sense, 5′ GCTGACAGCAGCTTTTGTGAACGTAGGCCCC 3′.

A bicistronic vector containing a kinase inactive mutant of sf-Stk (K190M) was generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit with the primer 5′ CAGACCCACTGTGCCATCATGTCTCTGAGTCGC 3′. Sf-Stk cloned into the pMX vector was mutated to obtain a constitutively activated version of the kinase (M330T) using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit and the primer 5′ CAAATGGACGGCACTGGAGAGCCTG 3′.

The pMX-IRES-EGFP backbone was used to generate pMX-gp55-IRES-EGFP and pMX-sfStk-IRES-EGFP as previously described (13).

Cell lines and virus preparations.

BaF3-EpoR cells (BaF3 cells engineered to express the murine EpoR) stably expressing sf-Stk (BaF3-EpoR/sf-Stk) (13) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM HEPES, and Epo (2 U/ml). BaF3-EpoR cells stably expressing SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk (BaF3-EpoR/sf-Stk/gp55) (13) were maintained in the same growth medium without Epo. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts and BOSC 23 cells (16) (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% FCS.

To generate infectious virus stocks of the pMX-gp55-sfStk bicistronic vector, Friend murine leukemia virus (F-MuLV)-infected NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with pSV2neo and the bicistronic vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Stable transfectants were selected after 2 weeks with G418 (0.4 mg/ml), and supernatants from these cells were used as a source of infectious virus. Infectious virus stocks of the pMX-gp55-sfStk bicistronic vector as well as the other pMX vectors used in this study were also generated by transient transfection of each pMX vector into BOSC23 ecotropic virus packaging cells (16), followed by supernatant collection at 48 h. F-MuLV was obtained from NIH 3T3 cells infected with F-MuLV clone 57.

Protein analysis.

Cell lysates were prepared by resuspending cells in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4 and aprotinin and leupeptin at 1 μg/ml each) followed by incubation on ice for 40 min. Insoluble components were removed by centrifugation, and protein concentration was determined with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Immunoprecipitations were performed as previously described (10) using anti-Stk polyclonal rabbit antibody (13) or antiphosphotyrosine antiserum (4G10) cross-linked to protein A-agarose (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.). Immunoprecipitated proteins or whole lysates were separated by electrophoresis on 8% Tris-glycine minigels (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions (35.2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Proteins were then transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose filters for Western blotting with anti-Stk antibody, anti-SFFV gp55 monoclonal antibody (7C10) (22), or antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology), followed by visualization using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.).

Metabolic labeling.

BaF3-EpoR cells that stably express sf-Stk alone or in conjunction with SFFV gp55 were starved for 30 min in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium lacking l-methionine and l-cysteine (Invitrogen), supplemented with 2% dialyzed FCS. Cells were subsequently incubated in the same medium with 100 μCi of 35S Easytag Express protein labeling mix (Perkin Elmer, Boston, Mass.) per ml for 1 h, followed by a chase period ranging from 30 min to 4 h in normal growth medium with 50 μg of cycloheximide per ml and a 10-fold excess of cysteine and methionine (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Cell lysates were prepared as described above, and 5 × 106 trichloroacetic acid-precipitable counts from each lysate was incubated with anti-Stk antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by collection of immune complexes using protein A/G-agarose beads. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on 8% Tris-glycine minigels and subjected to radioactive enhancement using the fluorographic reagent Amplify (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, N.J.). Gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography.

Colony-forming assays.

For the bone marrow colony-forming assay, NIH Swiss or C57BL/6 mice were injected with phenylhydrazine (60 mg/kg) intraperitoneally for two consecutive days to stimulate erythroid precursor production and sacrificed on the fifth day by carbon dioxide asphyxiation. Bone marrow cells were flushed from the femur under sterile conditions with Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Invitrogen). Cells (106) were incubated with virus for 1 h on ice, and then plated in a 24-well dish in 1% methylcellulose, 1% bovine serum albumin, 30% FCS, l-glutamine, penicillin-streptomycin solution, and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After 4 days of growth at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO, 100 μl of benzidine (2 mg/ml) was added to each well and hemoglobin-positive (blue) erythroid CFU (CFU-E) were enumerated by microscopic examination. The average number of colonies per well was calculated by totaling the number of colonies in four 2- by 2-mm defined square areas within a well and averaging these values for three to six wells per sample. The fetal liver colony-forming assays were performed as described above with liver cells from 14- to 15-day-old NIH Swiss or C57BL/6 embryos. One-tailed, paired Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance between samples.

Animal inoculations.

As a source of leukemic splenocytes, adult NIH Swiss mice were inoculated intravenously with 0.5 ml of tissue culture supernatant containing the F-MuLV/SFFV-P complex, and enlarged spleens were collected several weeks later. To test the biological effects of various pMX vectors in mice, infectious virus obtained from transfected BOSC23 cells was mixed with helper virus (F-MuLV) at a ratio of 4 parts vector to 1 part helper virus, and 0.5 ml was injected intravenously into normal adult NIH Swiss and C57BL/6 mice or mice that had been pretreated with phenylhydrazine (60 mg/kg on days 2 and 1 prior to virus injection). Newborn mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 ml of supernatant from BOSC23 cells transfected with each pMX vector. Four weeks later, they were injected intravenously with F-MuLV.

RESULTS

A bicistronic vector expressing SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk confers Epo-independent growth of erythroid cells from bone marrow and fetal liver of Fv-2rr mice.

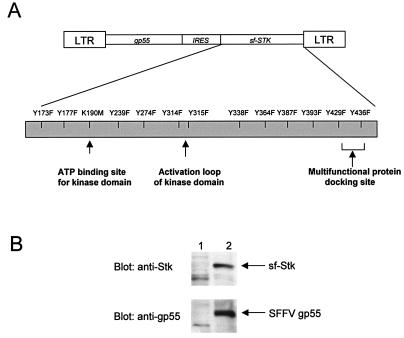

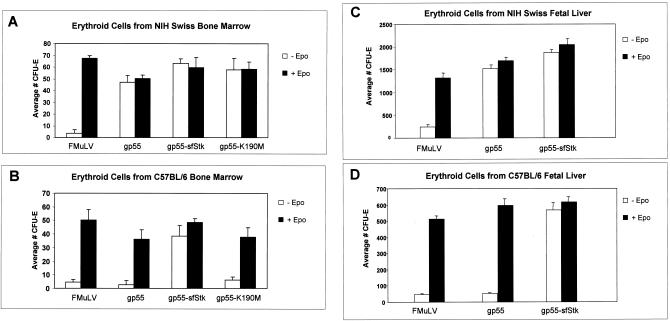

One of the hallmarks of early SFFV-induced disease is the induction of Epo-independent proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells, responsible for the splenic enlargement that is characteristic of the disease. This phenomenon can be studied ex vivo by assessing the colony-forming potential of erythroid progenitors in culture in the absence of exogenous Epo. We used this ex vivo system to determine whether SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk are sufficient to induce Epo-independent proliferation of erythroid cells from Fv-2rr mice, which do not express sf-Stk. To do this, we created a bicistronic retroviral vector termed pMX-gp55-sfStk that uses an internal ribosome entry sequence to coexpresses the gp55 and sf-Stk proteins (Fig. 1A). F-MuLV-infected NIH 3T3 cells were transfected with the bicistronic vector, and stably expressing clones were assessed for protein expression. As shown in Fig. 1B, both gp55 and sf-Stk are expressed in the stable transfectant selected for virus production. Infectious supernatant was collected from this clone and used to infect erythroid cells obtained from the bone marrow of phenylhydrazine-treated NIH Swiss (Fv-2ss) or C57BL/6 (Fv-2rr) mice. Cells were plated in methylcellulose medium and assessed for CFU-E formation in the presence or absence of exogenous Epo. Infection with F-MuLV helper virus alone had no effect on erythroid cells from either NIH Swiss or C57BL/6 mice in the absence of Epo (Fig. 2A and B). Erythroid cells from NIH Swiss mice (which express endogenous sf-Stk) but not C57BL/6 mice (which do not express sf-Stk) were susceptible to the colony-forming potential of SFFV gp55 alone, confirming that gp55 is sufficient to induce Epo-independent erythroid colony formation in Fv-2ss mice but not Fv-2rr mice (Fig. 2A and B). Although expression of sf-Stk alone failed to induce Epo-independent CFU-E formation (data not shown), infection of erythroid cells with the pMX-gp55-sfStk vector conferred Epo-independent CFU-E formation to erythroid cells from both Fv-2-resistant (C57BL/6) and -susceptible (NIH Swiss) mice, demonstrating that both SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk are required and sufficient for Epo-independent CFU-E formation in Fv-2rr mice. The same results were obtained with erythroid cells from fetal livers of NIH Swiss and C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2C and D). Interestingly, erythroid cells from the fetal livers of C57BL/6 mice form significantly fewer CFU-E than those from NIH Swiss mice, in the presence of either Epo or SFFV gp55-sfStk (compare Fig. 2C and D). In contrast, the numbers of Epo- or gp55/sfStk-induced CFU-E obtained using erythroid cells from adult bone marrow of NIH Swiss or C57BL/6 mice were equivalent (compare Fig. 2A and B).

FIG. 1.

Creation of a bicistronic retroviral vector encoding SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk. (A) Diagram of the vector. An enlargement of the sf-Stk protein region indicates the amino acid residues altered by site-directed mutagenesis. (B) Western blot analysis of uninfected NIH 3T3 cells (lanes 1) and NIH 3T3 cells expressing the bicistronic gp55-sfStk vector (lanes 2) with anti-Stk antiserum (top) or anti-SFFV gp55 serum (bottom).

FIG. 2.

Induction of Epo-independent CFU-E by a bicistronic vector expressing SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk. Erythroid cells prepared from the bone marrow of phenylhydrazine-treated NIH Swiss (A) or C57BL/6 (B) mice were infected with supernatant from F-MuLV-infected NIH 3T3 cells stably transfected with a vector encoding gp55 alone, a wild-type bicistronic vector expressing both gp55 and sf-Stk (gp55-sfStk), or a vector expressing gp55 and a kinase-inactive form of sf-Stk (gp55-K190M). Supernatant from F-MuLV-infected NIH 3T3 cells was included as a control. Cells were then plated in methylcellulose with or without Epo and erythroid colonies (CFU-E) were counted after 4 days. The same experiment was repeated with fetal livers from NIH Swiss (C) or C57BL/6 (D) mice as the source of erythroid cells. Values represent the average number of CFU-E in three to six wells of a 24-well dish.

The kinase domain of sf-Stk is required for Epo-independent colony formation by SFFV gp55.

It has been demonstrated that sf-Stk is phosphorylated in hematopoietic cells coexpressing EpoR and SFFVgp55 (14). To assess whether the kinase activity of sf-Stk is required for the induction of Epo independence by SFFV gp55, we generated a kinase-inactive mutant of the protein (K190M) and tested its ability to confer Epo-independent CFU-E formation. The kinase-inactive K190M mutant contains a lysine-to-methionine change within the ATP binding site of the tyrosine kinase domain (Fig. 1A). Compared to the bicistronic vector expressing gp55 and wild-type sf-Stk, the vector expressing gp55 and the kinase-inactive mutant (gp55-K190M) was unable to confer Epo-independent CFU-E formation to erythroid cells from Fv-2rr mice (Fig. 2B). No effect of this mutant was observed on erythroid cells from mice expressing endogenous wild-type sf-Stk (NIH Swiss) (Fig. 2A), indicating that the K190M mutant of sf-Stk does not function in a dominant negative manner in erythroid cells from Fv-2ss mice. The same results were obtained with erythroid cells from fetal livers of NIH Swiss or C57BL/6 mice (data not shown). These data demonstrate that the kinase activity of sf-Stk is crucial for gp55-mediated CFU-E formation in the absence of Epo.

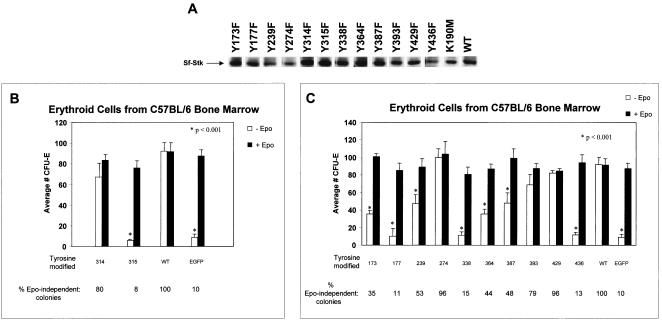

The kinase domain of sf-Stk also contains two tyrosine residues, Y314 and Y315, and erythroid cells from Fv-2-resistant mice expressing an sf-Stk construct lacking both of these tyrosines fail to form Epo-independent colonies after infection with SFFV (5). To assess the importance of these two sf-Stk tyrosines individually, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of each tyrosine residue to a phenylalanine residue within pMX-gp55-sfStk (Fig. 1A). The mutant vectors, which coexpress gp55 and each mutant of sf-Stk, were transiently transfected into the BOSC23 packaging cell line to produce ecotropic viruses. Expression of the variant sf-Stk proteins in these cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). Infectious supernatant was collected and used to assess the importance of each tyrosine residue in conjunction with SFFV gp55 for the induction of Epo-independent CFU-E. As shown in Fig. 3B, mutation of tyrosine 315, but not tyrosine 314, in sf-Stk had a statistically significant effect on the ability of the kinase to induce Epo-independent CFU-E formation when coexpressed with SFFV gp55 in Fv-2-resistant erythroid cells from C57BL/6 mice, which do not express endogenous sf-Stk. The number of Epo-independent colonies formed when cells expressing the Y314F mutant were used was almost as high as that obtained with cells expressing wild-type sf-Stk, while cells expressing theY315F mutant failed to form any Epo-independent CFU-E above background levels when the mutant was coexpressed with SFFV gp55. Neither vector interfered with the ability of SFFV gp55 to induce Epo-independent CFU-E using erythroid cells from Fv-2-susceptible NIH Swiss mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Induction of Epo-independent erythroid colonies by a bicistronic vector expressing SFFV gp55 and tyrosine mutants of sf-Stk. Infectious viral supernatants were generated by transfecting BOSC23 packaging cells with the bicistronic vector expressing SFFV gp55 and either wild-type sf-Stk (WT) or various tyrosine mutants of sf-Stk. Expression of wild-type and mutant sf-Stk in these cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis (A). The supernatants were used to infect erythroid cells prepared from the bone marrow of phenylhydrazine-treated C57BL/6 mice, which were subsequently plated in methylcellulose with or without Epo and assessed for CFU-E formation as previously described (B and C). Values are average numbers of CFU-E in three to six separate wells of a 24-well dish; mutants represented on the graph were not tested simultaneously. The percentage of Epo-independent colonies induced by each construct is shown at the bottom of each figure. EGFP represents erythroid cells infected with the supernatant from the BOSC23 packaging cell line transfected with the enhanced green fluorescent protein vector alone. Values for Epo-negative wells that are statistically different from those for the respective Epo-positive wells (as determined by Student's t test) are indicated by asterisks.

Additional tyrosine residues outside the kinase domain of sf-Stk are required for gp55-mediated CFU-E formation.

Like other Met-related receptor tyrosine kinases, Stk contains a multifunctional docking site (7, 23) (Fig. 1A) and within this domain tyrosine 436, but not tyrosine 429, has been shown to be important for the induction of Epo-independent CFU-E in SFFV-infected cells (5). In addition to tyrosines 429 and 436 within the multifunctional docking site and tyrosines 314 and 315 within the kinase domain, sf-Stk contains eight other tyrosine residues that may also play a role in the formation of Epo-independent erythroid colonies after SFFV infection. To assess the importance of these other sf-Stk tyrosines in SFFV-dependent CFU-E formation, we performed site-directed mutagenesis of these eight tyrosine residues, as well as tyrosines 429 and 436, to phenylalanine residues within pMX-gp55-sfStk (Fig. 1A). The mutant vectors, which coexpress gp55 and each mutant of sf-Stk, were transiently transfected into packaging cells and infectious supernatant was collected as described above. Mutagenesis of sf-Stk did not prevent expression of the variant proteins as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A). Erythroid cells from Fv-2-resistant C57BL/6 mice, which do not express endogenous sf-Stk, were then infected with each mutant and CFU-E assays performed. As shown in Fig. 3C, mutation of tyrosines 173, 177, 239, 338, 364, 387, and 436, but not tyrosines 274, 393, and 429, in sf-Stk had a statistically significant effect on the ability of the kinase to induce Epo-independent CFU-E formation when coexpressed with SFFV gp55. The most notable reduction in CFU-E number was observed when tyrosines 177, 338, and 436 of sf-Stk were mutated, resulting in colony numbers well below 20% of the corresponding Epo-positive controls. The failure of some sf-Stk tyrosine mutants to induce Epo-independent CFU-E in conjunction with gp55 was not due to lack of expression of gp55 sequences within the vector because all vectors induced high numbers of Epo-independent CFU-E when expressed in erythroid cells from Fv-2 sensitive NIH Swiss mice, which express endogenous sf-Stk (data not shown). The failure of any of the sf-Stk tyrosine mutants to interfere with the ability of SFFV gp55 to induce Epo-independent CFU-E in Fv-2-sensitive cells indicates that these mutants do not have a dominant negative effect on wild-type sf-Stk.

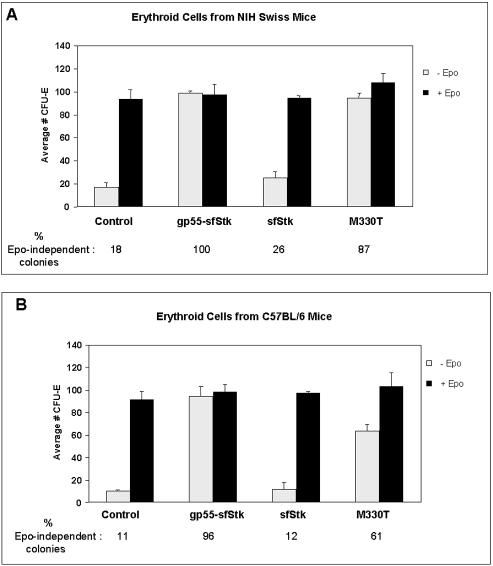

A constitutively active form of sf-Stk induces Epo-independent colony formation in the absence of SFFV gp55.

Stk/Ron belongs to a family of receptor tyrosine kinases that includes c-Met, the product of a proto-oncogene found to be upregulated in several human cancers (3, 4). Missense mutations of c-Met have been described in hereditary papillary renal carcinoma (19). One of these mutations is localized to the conserved tyrosine kinase domain of c-Met, and biochemical analysis of this mutant (M1268T) revealed that it has constitutive tyrosine kinase activity (8). A homologous mutation generated in the Ron gene, the human counterpart of the Stk gene, was also found to display constitutive activation and transforming activity (21). We generated this mutation within the sf-Stk protein (M330T) and found that the mutant protein is highly phosphorylated in BOSC23 cells in the absence of SFFV gp55 (data not shown). In order to determine if the M330T mutant of sf-Stk is able to confer Epo-independent CFU-E formation, erythroid cells from Fv-2ss and Fv-2rr mice were infected with the supernatant from transiently transfected BOSC23 cells and assessed for colony forming potential in the absence of Epo. As shown in Fig. 4, the M330T mutant was able to induce Epo-independent CFU-E formation on erythroid cells from the bone marrow of both Fv-2-susceptible NIH Swiss and Fv-2-resistant C57BL/6 mice in the absence of SFFV gp55, although the mutant induced a higher percentage of Epo-independent colonies after infecting NIH Swiss erythroid cells than with C57BL/6 cells (87% versus 61%). Expression of wild-type sf-Stk alone did not induce significant Epo-independent colony formation over background in erythroid cells from either strain, although the basal level of Epo-independent CFU-E is higher with erythroid cells from NIH Swiss mice than with cells from C57BL/6 mice (18% versus 11%).

FIG. 4.

Induction of Epo-independent erythroid colonies by a retroviral vector expressing a constitutively active mutant of sf-Stk. Erythroid cells obtained from the bone marrow of NIH Swiss (A) or C57BL/6 (B) mice were infected with supernatants from the BOSC23 packaging cell line transiently transfected with pMX-EGFP (control), pMX-gp55-sfStk (gp55-sfStk), pMX-sfStk-EGFP (sfStk), or pMX-M330T (M330T). Cells were then plated in methylcellulose with or without Epo, and erythroid colonies (CFU-E) were counted after 4 days. Values are average numbers of CFU-E in three to six separate wells of a 24-well dish. The percentage of Epo-independent colonies induced by each construct is shown at the bottom of each chart.

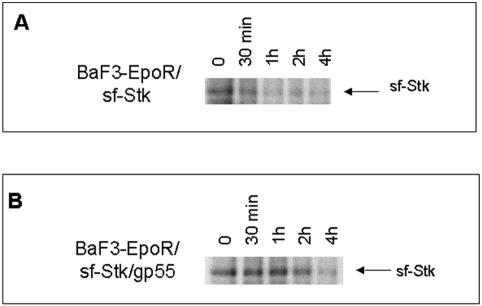

Prolonged half-life of sf-Stk in the presence of gp55.

Previous experiments have demonstrated a strong interaction between sf-Stk and the Epo receptor in BaF3-EpoR cells expressing SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk. In cells lacking gp55, this interaction was weak and did not result in tyrosine phosphorylation of sf-Stk or its interaction with downstream signaling molecules, even in the presence of Epo (13). These data suggest that SFFV gp55 either may stabilize sf-Stk or may function to bring sf-Stk to the cell surface, where it can interact with the EpoR complex. To test the hypothesis that SFFV gp55 stabilizes sf-Stk, pulse-chase experiments were performed with variants of the BaF3-EpoR cell line. Cells expressing sf-Stk alone (BaF3-EpoR/sf-Stk) or gp55 and sf-Stk (BaF3-EpoR/sf-Stk/gp55) were pulsed with 35S-methionine/cysteine, washed, and incubated in complete medium containing cycloheximide and excess unlabeled methionine-cysteine for a period of minutes to hours. Lysates were prepared from the cells, immunoprecipitated with anti-Stk antiserum, and subjected to gel electrophoresis, fluorography, and autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 5, sf-Stk is detectable for a longer period in cells expressing both sf-Stk and SFFVgp55 than in cells expressing sf-Stk alone. While the levels of sf-Stk in BaF3EpoR/sf-Stk cells (Fig. 5A) decline within 30 min, short-form Stk is still expressed in the BaF3EpoR/sf-Stk/gp55 cells (Fig. 5B) for at least 4 h. These data, coupled with previous observations (13), suggests that direct interaction between SFFV gp55 and sf-Stk results in the stabilization of the kinase.

FIG. 5.

The half-life of sf-Stk is prolonged when it is coexpressed with SFFV gp55. BaF3-EpoR cells expressing sf-Stk or sf-Stk and wild-type SFFV gp55 were pulsed with [35S]methionine-cysteine and chased for various amounts of time in regular medium supplemented with cycloheximide and a 10-fold excess of unlabeled methionine and cysteine (see Materials and Methods). Lysates were prepared from the cells, immunoprecipitated with anti-Stk antisera, and subjected to autoradiography.

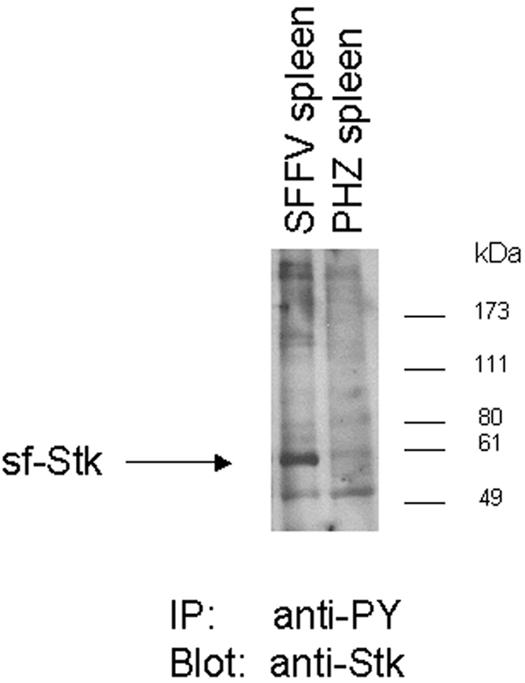

Sf-Stk is phosphorylated in spleens from SFFV-infected mice.

Sf-Stk has been implicated in SFFV pathogenesis, as mice lacking this protein (Fv-2rr mice) are not susceptible to disease (17). We have previously demonstrated that sf-Stk is constitutively phosphorylated in a hematopoietic cell line expressing gp55 (13). In order to determine if sf-Stk is phosphorylated in the spleens of SFFV-infected mice, lysates were prepared from the spleens of NIH Swiss mice infected with SFFV or uninfected control mice treated with phenylhydrazine to stimulate erythroblast proliferation. As shown in Fig. 6, phosphorylated sf-Stk was detected in splenic lysates from mice infected with SFFV but not from phenylhydrazine-treated control mice. Thus, sf-Stk is activated by SFFV gp55 not only in vitro but also in vivo.

FIG. 6.

Expression of phosphorylated sf-Stk in splenocytes from SFFV-infected mice. Spleens were prepared from NIH Swiss mice infected with F-MuLV/SFFV-P (SFFV spleen) or from uninfected control mice injected with phenylhydrazine (PHZ spleen). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antiphosphotyrosine antiserum (4G10) cross-linked to protein A-agarose, resolved on an 8% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel, and subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-Stk antiserum. Migration of molecular mass markers is indicated.

Biological effects of pMX-gp55-sfStk and pMX-M330T in Fv-2-susceptible and -resistant strains of mice.

Since pMX-gp55-sfStk was able to induce erythroid cells from Fv-2rr mice to form Epo-independent colonies ex vivo, we tested the ability of this vector to induce disease in Fv-2-resistant mice. Adult NIH Swiss (Fv-2ss) and C57BL/6 (Fv-2rr) mice were pretreated with phenylhydrazine to increase the number of erythroid target cells and then infected with pMXgp55-sfStk plus F-MuLV helper virus. As shown in Table 1, Expt 1, 100% of adult NIH Swiss mice pretreated with phenylhydrazine and then infected with the gp55-sfStk vector developed splenomegaly between 29 and 36 days postinfection, characteristic of SFFV-induced disease. In contrast, none of the C57BL/6 mice infected with the same vector developed any clinical signs over a 2-month period. When untreated adult NIH Swiss mice were injected with the gp55-sfStk vector (Table 1, Expt 2), they also developed splenomegaly between 33 and 45 days postinfection. In addition, a high percentage of these mice (50%) exhibited clinical signs not previously associated with SFFV infection, including enlarged lymph nodes and ovarian and uterine tumors. Preliminary pathological analysis of these tumors indicates that they may be hemangiosarcomas. Injection of the same virus into untreated C57BL/6 mice failed to induce any clinical signs. When newborn NIH Swiss and C57BL/6 mice were injected with pMX-gp55-sfStk, both strains failed to develop the splenomegaly characteristic of erythroid disease, but a high percentage of each strain developed enlarged thymuses and hemorrhaged into the thoracic cavity after latencies of 26 to 60 days (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Induction of disease in mice with sf-Stk viral constructs

| Expt | Strain | Fv-2 genotype | Virus | No. of diseased mice/no. injected | Clinical sign(s)a | Latency (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | NIH Swiss | ss | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 10/10 | Splenomegaly (1.3 g) | 29-36 |

| C57BL/6 | rr | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 0/10 | |||

| 2c | NIH Swiss | ss | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 10/10 | Splenomegaly (0.7 g), enlarged lymph nodes, ovarian and uterine tumors | 33-45 |

| C57BL/6 | rr | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 0/10 | |||

| 3d | NIH Swiss | ss | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 5/8 | Enlarged thymus; hemorrhage | 26-60 |

| NIH Swiss | ss | pMX-M330T + F-MuLV | 8/10 | Splenomegaly (1.4 g) | 43-60 | |

| NIH Swiss | ss | Medium + F-MuLV | 0/10 | |||

| C57BL/6 | rr | pMX gp55-sfStk + F-MuLV | 6/8 | Enlarged thymus and lymph nodes; hemorrhage | 26-41 | |

| C57BL/6 | rr | pMX-M330T + F-MuLV | 0/10 | |||

| C57BL/6 | rr | Medium + F-MuLV | 0/10 |

Numbers in parentheses are average spleen weights.

Adult mice pretreated with phenylhydrazine to increase erythroid target cells were injected intraveneously with 0.5 ml of a 5:1 mixture of supernatant from BOSC23 packaging cells transfected with pMXgp55-sfStk and supernatant from F-MuLV-infected NIH 3T3 cells. Mice were sacrificed when morbid or 60 days after virus injection. Twenty percent of NIH Swiss mice injected with F-MuLV alone developed splenomegaly after 2 months.

Adult mice were injected intraveneously with 0.5 ml of a 5:1 mixture of supernatant from BOSC23 packaging cells transfected with pMXgp55-sfStk and supernatant from F-MuLV- infected NIH 3T3 cells. Mice were sacrificed when morbid or 60 days after virus injection. Mice injected with F-MuLV alone failed to develop any clinical signs within 2 months. NIH Swiss mice injected with pMXgp55 developed only erythroleukemia.

Newborn mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 ml of supernatant from BOSC23 packaging cells transfected with each vector. Control mice were given 0.1 ml of medium. At 4 weeks, all mice were injected intraveneously with F-MuLV. Mice were sacrificed when morbid or 60 days after the first virus injection.

To determine whether the constitutively active mutant of sf-Stk could also cause disease in the absence of SFFV gp55, mice were injected with the mutant M330T virus plus F-MuLV as a helper. Compared with adult NIH Swiss mice injected with the gp55-sfStk vector, all of which developed clinical signs of disease within 45 days, NIH Swiss adults were relatively resistant to disease induction by the M330T virus, with only a small percentage developing splenomegaly after a 2-month latency, similar to the incidence of splenomegaly in adult mice given F-MuLV alone (data not shown). Adult C57BL/6 mice were completely resistant to the M330T virus. However, the constitutively active mutant of sf-Stk induced a high incidence (80%) of splenomegaly over a 60-day period when injected into newborn NIH Swiss, but not C57BL/6, mice (Table 1, Expt 3). Unlike mice injected as newborns with the gp55-sfStk vector, none of the mice injected with the constitutively active sf-Stk mutant developed enlarged thymuses or lymph nodes or showed signs of hemorrhage.

DISCUSSION

The development of erythroleukemia following SFFV infection is a complex process that occurs in several stages, beginning with an acute erythroid hyperplasia in the spleen, followed by the emergence of fully transformed erythroid cells that spread throughout the body. During the early stage of disease, SFFV-infected erythroblasts develop the abnormal ability to proliferate and differentiate in the absence of erythropoietin. This Epo-independent polyclonal expansion of erythroid cells results from the constitutive activation of Epo signal transduction pathways by the SFFV envelope protein, gp55. Recent experiments have demonstrated that SFFV pathogenesis also requires expression of a specific cellular protein, the receptor tyrosine kinase sf-Stk (17). We have previously shown that sf-Stk binds to gp55 in hematopoietic cells expressing the EpoR, resulting in activation of the kinase and its association with multiple phosphorylated signal transduction molecules (13). The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the mechanism by which sf-Stk contributes to the induction of erythroid hyperplasia by SFFV gp55. Our studies confirm that sf-Stk is indeed phosphorylated in SFFV-infected spleens, and we demonstrate conclusively that gp55 and sf-Stk are sufficient for the ex vivo induction of Epo-independent erythroid colonies. Further, we provide evidence that additional tyrosine residues outside of the kinase domain and multifunctional docking site of the sf-Stk protein are required for the ex vivo induction of gp55-mediated erythroid hyperplasia.

For these studies, we designed a bicistronic retroviral vector that coexpresses gp55 and sf-Stk. Infectious supernatant was harvested from transfected packaging cells and used to infect bone marrow cells enriched for erythroid progenitors, which were subsequently grown in methylcellulose to assess their potential for CFU-E formation in the absence of exogenous Epo. This assay provides an excellent measure of the early erythroid hyperplasia that occurs in SFFV-infected animals, during which infected erythroblasts are able to proliferate and differentiate without stimulation by extracellular erythropoietin. Using this system with erythroid cells from Fv-2rr mice, which lack endogenous sf-Stk, we confirmed that gp55 and sf-Stk are sufficient for the induction of Epo-independent CFU-E from bone marrow and fetal liver erythroid cells.

The colony assay system was further utilized to test the importance of certain amino acid residues within sf-Stk for the induction of gp55-mediated erythroid hyperplasia. Our studies demonstrate that mutation of both the ATP-binding site (K190M) and one of the tyrosines within the catalytic region of the kinase domain (Y315) of sf-Stk abolished Epo-independent CFU-E formation by SFFV gp55 in bone marrow cells from Fv-2rr mice. These findings support a role for the kinase domain in sf-Stk function and, in conjunction with our data demonstrating sf-Stk phosphorylation in SFFV-infected spleens (Fig. 6), suggest that sf-Stk is an active kinase in SFFV-infected erythroid cells. The interaction between sf-Stk and gp55 may induce a conformational change in sf-Stk such that it assumes a conformation that leads to its activation, similar to what has been reported for the constitutively active mutant of Met found in sporadic human tumors. This Met mutant, M1250T, exhibits a lower threshold for activation and does not require phosphorylation of Tyr1234 (homologous to Tyr314 of sf-Stk) for full activation of the kinase (1). It is noteworthy that mutagenesis of Tyr314 within sf-Stk had no effect on gp55-mediated sf-Stk function in our system (Fig. 3B). It is also possible that interaction with gp55 may raise the catalytic efficiency of sf-Stk, alter its substrate specificity, or permit phosphorylation of specific tyrosines that can be used as docking sites for downstream mediators.

Amino acid residues outside of the kinase domain were also mutated (Tyr-to-Phe mutagenesis) to assess their importance in sf-Stk function. Our data reveal that all tyrosines except Y274, Y393, and Y429 are required for Epo-independent CFU-E induction by gp55. While it was previously reported that tyrosines within the kinase domain (Y314/315) and the multifunctional docking site (Y436) are important for CFU-E formation (5), this report is the first evidence that other tyrosines within sf-Stk (Y173, Y177, Y239, Y338, Y364, and Y387) are also required for sf-Stk function in erythroid progenitor cells. The functional role of these tyrosines is not known, although it has been suggested that Y364 is a potential c-src phosphorylation site (2). The mechanism by which alteration of these tyrosine residues impairs the ability of sf-Stk to induce Epo-independent erythroid colonies in the presence of SFFV gp55 is still unclear. Mutation of these residues could affect protein folding, membrane localization, or interaction with gp55. It is also possible that the phosphorylation of these particular tyrosine residues may contribute to wild-type sf-Stk function, either by mediating interactions with SH2-containing signal transduction molecules or by playing a role in the transactivation of adjacent sf-Stk molecules following interaction with SFFV gp55. Analysis of the motifs surrounding each of the tyrosines in sf-Stk that are important for gp55-mediated CFU-E formation reveals only one, AY436VNV, that matches a consensus sequence for known signal transducing molecules. When phosphorylated, this site can serve as a binding site for many of the signal transducing molecules previously shown to be activated in SFFV-infected cells (13).

Coexpression of sf-Stk and SFFV gp55 not only leads to phosphorylation of sf-Stk but also significantly extends the half-life of the kinase. Based upon previous studies (13), the extended half-life of sf-Stk when coexpressed with SFFV gp55 probably requires the interaction of the viral protein with the kinase. It was previously shown that coexpression with SFFV gp55 also extends the half-life of the EpoR (24). Thus, interaction of SFFV gp55 with both the EpoR and sf-Stk results in a stable, activated complex that is expressed long enough to provide the constitutive stimulation of Epo signal transduction that contributes to SFFV disease.

The ability of gp55 and sf-Stk to stimulate Epo-independent proliferation of erythroid cells in fetal liver as well as in bone marrow provides further support for a role of sf-Stk in erythropoiesis, as the kinase is capable of stimulating intracellular signaling in both fetal and adult hematopoietic systems. Although the normal function of sf-Stk is still unknown, its presence in fetal liver cells (17) supports the hypothesis that it may play a physiological role in that tissue. The fact that amino acid residues within the kinase domain of sf-Stk are required for CFU-E formation in both cell types indicates that the protein likely functions as an active kinase in both systems. Furthermore, the ability of the bicistronic vector to induce Epo-independent CFU-E in fetal liver suggests that it may be useful for studying the biological effects of SFFV in knockout mice that have been generated in an Fv-2rr background but are embryonic lethal. Such studies are currently being pursued in our lab with fetal liver cells from mice which lack genes for certain signal transduction components.

In addition to the colony assays, we also examined the ability of activated sf-Stk to induce disease in mice. Despite the fact that the vectors expressing SFFV gp55/sf-Stk and the constitutively activated sf-Stk mutant induced erythroid cells from Fv-2rr C57BL/6 mice to form Epo-independent colonies in vitro, neither was able to induce erythroleukemia when injected into C57BL/6 mice, even if the mice had been pretreated with phenylhydrazine to increase the number of erythroid target cells. In contrast, both viruses caused erythroleukemia in Fv-2ss NIH Swiss mice. Thus, activated sf-Stk, while sufficient to cause erythroid disease in Fv-2-susceptible NIH Swiss mice, is unable to induce erythroleukemia in Fv-2-resistant C57BL/6 mice. The robust immune system of C57BL/6 mice (6, 20) may account for some of this resistance, as well as differences in erythroid cell cycling in these mice (9). Studies are currently under way to repeat these in vivo experiments in other strains of Fv-2rr mice that may not have as vigorous an immune response, including a congenic DDD strain carrying the Fv-2rr allele and C57BL/6 nude mice. In addition, we are attempting to reduce the immune response in the C57BL/6 mice by pretreatment with CpG oligonucleotides, a treatment that was recently shown to be effective in overcoming the strong immunity of certain strains of mice to Friend virus complex (15). Attempts to induce erythroleukemia in C57BL/6 mice by infecting them as neonates, during a time of immunological immaturity, were ineffective. In fact, both NIH Swiss and C57BL/6 mice infected as newborns developed clinical signs not previously associated with SFFV infection, including enlarged lymphoid organs and hemorrhage. Unusual clinical symptoms, including enlarged lymph nodes and ovarian and uterine tumors, were also observed in half of the adult NIH Swiss mice injected with the gp55-sfStk bicistronic vector. Preliminary analysis suggests that gp55-activated sf-Stk may be causing hemangiosarcomas in these mice. Interestingly, sf-Stk activated by point mutation appears to cause only erythroleukemia. Studies are in progress to determine the mechanism by which SFFV gp55-activated sf-Stk induces nonerythroid disease in Fv-2-susceptible and -resistant strains of mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joan Cmarik for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiara, F., P. Michieli, L. Pugliese, and P. M. Comoglio. 2003. Mutations in the met oncogene unveil a “dual switch” mechanism controlling tyrosine kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29352-29358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danilkovitch-Miagkova, A., and E. J. Leonard. 2001. Cross-talk between RON receptor tyrosine kinase and other transmembrane receptors. Histol. Histopathol. 16:623-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Renzo, M. F., M. Olivero, S. Ferro, M. Prat, I. Bongarzone, S. Pilotti, A. Belfiore, A. Costantino, R. Vigneri, M. A. Pierotti, and P. M. Comoglio. 1992. Overexpression of the c-MET/HGF receptor gene in human thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene 7:2549-2553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Renzo, M. F., M. Olivero, D. Katsaros, T. Crepaldi, P. Gaglia, P. Zola, P. Sismondi, and P. M. Comoglio. 1994. Overexpression of the Met/HGF receptor in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 58:658-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finkelstein, L. D., P. A. Ney, Q. P. Liu, R. F. Paulson, and P. H. Correll. 2002. Sf-Stk kinase activity and the Grb2 binding site are required for Epo-independent growth of primary erythroblasts infected with Friend virus. Oncogene 21:3562-3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasenkrug, K. J. 1999. Lymphocyte deficiencies increase susceptibility to Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia in Fv-2 genetically resistant mice. J. Virol. 73:6468-6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwama, A., N. Yamaguchi, and T. Suda. 1996. STK/RON receptor tyrosine kinase mediates both apoptotic and growth signals via the multifunctional docking site conserved among the HGF receptor family. EMBO J. 15:5866-5875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeffers, M., L. Schmidt, N. Nakaigawa, C. P. Webb, G. Weirich, T. Kishida, B. Zbar, and G. F. Vande Woude. 1997. Activating mutations for the met tyrosine kinase receptor in human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11445-11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melkun, E., M. Pilione, and R. F. Paulson. 2002. A naturally occurring point substitution in Cdc25A, and not Fv2/Stk, is associated with altered cell-cycle status of early erythroid progenitor cells. Blood 100:3804-3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muszynski, K. W., T. Ohashi, C. Hanson, and S. K. Ruscetti. 1998. Both the polycythemia- and anemia-inducing strains of Friend spleen focus-forming virus induce constitutive activation of the Raf-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. J. Virol. 72:919-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ney, P. A., and A. D. D'Andrea. 2000. Friend erythroleukemia revisited. Blood 96:3675-3680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishigaki, K., C. Hanson, T. Ohashi, D. Thompson, K. Muszynski, and S. Ruscetti. 2000. Erythroid cells rendered erythropoietin independent by infection with Friend spleen focus-forming virus show constitutive activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt kinase: involvement of insulin receptor substrate-related adapter proteins. J. Virol. 74:3037-3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishigaki, K., D. Thompson, C. Hanson, T. Yugawa, and S. Ruscetti. 2001. The envelope glycoprotein of Friend spleen focus-forming virus covalently interacts with and constitutively activates a truncated form of the receptor tyrosine kinase Stk. J. Virol. 75:7893-7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohashi, T., M. Masuda, and S. K. Ruscetti. 1995. Induction of sequence-specific DNA-binding factors by erythropoietin and the spleen focus-forming virus. Blood 85:1454-1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olbrich, A., S. Schimmer, and U. Dittmer. 2003. Preinfection treatment of resistant mice with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides renders them susceptible to Friend retrovirus-induced leukemia. J. Virol. 77:10658-10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pear, W. S., G. P. Nolan, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persons, D. A., R. F. Paulson, M. R. Loyd, M. T. Herley, S. M. Bodner, A. Bernstein, P. H. Correll, and P. A. Ney. 1999. Fv2 encodes a truncated form of the Stk receptor tyrosine kinase. Nat. Genetics 23:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruscetti, S. K. 1999. Deregulation of erythropoiesis by the Friend spleen focus-forming virus. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31:1089-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt, L., F. M. Duh, F. Chen, T. Kishida, G. Glenn, P. Choyke, S. W. Scherer, Z. Zhuang, I. Lubensky, M. Dean, R. Allikmets, A. Chidambaram, U. R. Bergerheim, J. T. Feltis, C. Casadevall, A. Zamarron, M. Bernues, S. Richard, C. J. Lips, M. M. Walther, L. C. Tsui, L. C. Geil, M. L. Orcutt, T. Stackhouse, and B. Zbar. 1997. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat. Genetics 16:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van der Gaag, H. C., and A. A. Axelrad. 1990. Friend virus replication in normal and immunosuppressed C57BL/6 mice. Virology 177:837-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams, T. A., P. Longati, L. Pugliese, P. Gual, A. Bardelli, and P. Michieli. 1999. MET(PRC) mutations in the Ron receptor result in upregulation of tyrosine kinase activity and acquisition of oncogenic potential. J. Cell Physiol. 181:507-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff, L., R. Koller, and S. Ruscetti. 1982. Monoclonal antibody to spleen focus-forming virus-encoded gp52 provides a probe for the amino-terminal region of retroviral envelope proteins that confers dual tropism and xenotropism. J. Virol. 43:472-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao, Z. Q., Y. Q. Chen, and M. H. Wang. 2000. Requirement of both tyrosine residues 1330 and 1337 in the C-terminal tail of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase for epithelial cell scattering and migration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267:669-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimura, A., A. D. D'Andrea, and H. F. Lodish. 1990. Friend spleen focus-forming virus glycoprotein gp55 interacts with the erythropoietin receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum and affects receptor metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4139-4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]