Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the 10-year course of the psychosocial functioning of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Method

The social and vocational functioning of 290 inpatients meeting both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for BPD and 72 axis II comparison subjects were carefully assessed during their index admission. Psychosocial functioning was reassessed using similar methods at five contiguous two-year time periods.

Results

Borderline patients without good psychosocial functioning at baseline reported difficulty attaining it for the first time. Those who had such functioning at baseline reported difficulty retaining and then regaining it. In addition, over 90% of their poor psychosocial functioning was due to poor vocational but not social performance.

Conclusions

Good psychosocial functioning that involves both social and vocational competence is difficult for borderline patients to achieve and maintain over time. In addition, their vocational functioning is substantially more compromised than their social functioning.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, psychosocial functioning, longitudinal course

Clinical experience suggests that the psychosocial functioning of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD) over time is varied. The psychosocial functioning of some borderline patients improves steadily with time, while that of others stalls at a relatively low level or actually deteriorates to the level of chronic impairment.

In terms of earlier studies, four large-scale, long-term follow-back studies of the longitudinal course of BPD were conducted in the 1980s (1–4). The borderline patients in three of these studies were found to have compromised social and vocational functioning (1,2,4). More recent prospective studies of the longitudinal course of BPD have found similar impairment in the psychosocial realm (5,6).

The current study, which is an extension of one of the more recent studies mentioned above (the McLean Study of Adult Development or MSAD), assesses the attainment and maintenance of good psychosocial functioning in a sample of 362 former inpatients: 290 with BPD and 72 axis II comparison subjects.

Methods

All subjects were initially inpatients at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Each patient was first screened to determine that he or she: 1) was between the ages of 18–35; 2) had a known or estimated IQ of 71 or higher; 3) had no history or current symptoms of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar I disorder, or an organic condition that could cause psychiatric symptoms; and 4) was fluent in English.

After the study procedures were explained, written informed consent was obtained. Each patient then met with a masters-level interviewer blind to the patient’s clinical diagnoses for a thorough psychosocial and treatment history as well as diagnostic assessment. Four semistructured interviews were administered. These interviews were: 1) the Background Information Schedule (BIS) (which assesses psychosocial functioning and treatment history) (7), 2) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (8), 3) the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) (9), and 4) the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-III-R Personality Disorders (DIPD-R) (10). The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the BIS (5) and of the three diagnostic measures (11,12) have all been found to be good-excellent.

At each of five follow-up waves, separated by 24 months, psychosocial functioning as well as axis I and/II psychopathology were reassessed via interview methods similar to the baseline procedures by staff members blind to previously collected information. After informed consent was obtained, our diagnostic battery was readministered (a change version of the SCID-I pertaining only to the past two years, the DIB-R, and the DIPD-R). The Revised Borderline Follow-up Interview (BFI-R)—the follow-up analog to the BIS administered at baseline—was also administered at each follow-up period to assess psychosocial functioning and treatment utilization during the past two years (5). Good-excellent inter-rater reliability was maintained throughout the course of the study for variables pertaining to psychosocial functioning (5). Good-excellent inter-rater reliability was also maintained for both axis I and II disorders (11,12).

Definition of Good Psychosocial Functioning

We defined good psychosocial functioning as having at least one emotionally sustaining relationship and a successful work/school record. A good or emotionally sustaining relationship was defined as one that involved at least weekly contact and was judged by the patient to be close, without elements of either abuse or neglect. In addition, this relationship had to be with a close friend and/or romantic partner and not a relative. A successful vocational record was defined by three elements: performing well at work or school, being vocationally engaged on a full-time basis, and being able to work or go to school in a sustained manner (i.e., consistently functioning in the vocational realm for at least 50% of the follow-up period). Being a stay-at-home houseperson was counted as full-time work and taking care of one’s children and home in a competent manner was counted as a successful vocational record.

Statistical Analyses

Cox proportional survival analyses were used to assess time-to-attainment of good psychosocial functioning. We defined time-to-attainment of good psychosocial functioning as the follow-up period at which this outcome was first achieved for those borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects who did not have good psychosocial functioning at baseline. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons first achieving this outcome during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first achieving this outcome during the second follow-up period, etc. Cox proportional survival analyses were also used to assess time to the loss of good psychosocial functioning. We defined time-to-loss of good psychosocial functioning as the follow-up period at which good psychosocial functioning was first lost for those borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects who had good psychosocial functioning at baseline. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 years, with time=2 years for persons first losing good psychosocial functioning during the first follow-up period, time=4 years for persons first losing good psychosocial functioning during the second follow-up period, etc. In addition, Cox proportional survival analyses were used to assess time-to-reattainment of good psychosocial functioning. We defined time-to-reattainment of good psychosocial functioning as the number of years after losing good psychosocial functioning that was present at baseline that it was first regained. Thus, possible values for this outcome were 2, 4, 6, or 8 years after first losing their initially high level of psychosocial functioning. Statistical significance required 2-tailed p<0.05.

Results

Two hundred and ninety patients met both DIB-R and DSM-III-R criteria for BPD and 72 met DSM-III-R criteria for at least one nonborderline axis II disorder (and neither criteria set for BPD) during their index admission, which was, on average, six days in length. Of these 72 comparison subjects, 4% met DSM-III-R criteria for an odd cluster personality disorder, 33% met DSM-III-R criteria for an anxious cluster personality disorder, 18% met DSM-III-R criteria for a nonborderline dramatic cluster personality disorder, and 53% met DSM-III-R criteria for personality disorder not otherwise specified (which was operationally defined in the DIPD-R as meeting all but one of the required number of criteria for at least two of the 13 axis II disorders described in DSM-III-R).

Baseline demographic data have been reported before (13). Briefly, 77.1% (N=279) of the subjects were female and 87% (N=315) were white. The average age of the subjects was 27 years (SD=6.3), the mean socioeconomic status was 3.3 (SD=1.5) (where 1=highest and 5=lowest), and their mean GAF score was 39.8 (SD=7.8) (indicating major impairment in several areas, such as work or school, family relations, judgment, thinking, or mood). In addition, the subjects had, on average, been psychiatrically ill for 8.8 years (SD=6.8).

In terms of continuing participation, 275 borderline patients were reinterviewed at two years, 269 at four years, 264 at six years, 255 at eight years, and 249 at ten years. In terms of axis II comparison subjects, 67 were reinterviewed at two years, 64 at four years, 63 at six years, 61 at eight years, and 60 at ten years. At the ten-year assessment, 41 borderline patients were no longer in the study: 12 had committed suicide, seven died of other causes, nine discontinued their participation, and 13 were lost to follow-up. By this time, 12 axis II subjects were no longer participating in the study: one had committed suicide, four discontinued their participation, and seven were lost to follow-up. All told, 90.4% (N=309) of surviving patients were reinterviewed at all five follow-up waves.

At baseline, 25.9% of borderline patients (N=75/290) and 58.3% of axis II comparison subjects (N=42/72) had had good psychosocial functioning in the two years prior to their index admission. Or looked at another way, 215 borderline patients and 30 axis II comparison subjects did not have good psychosocial functioning at baseline.

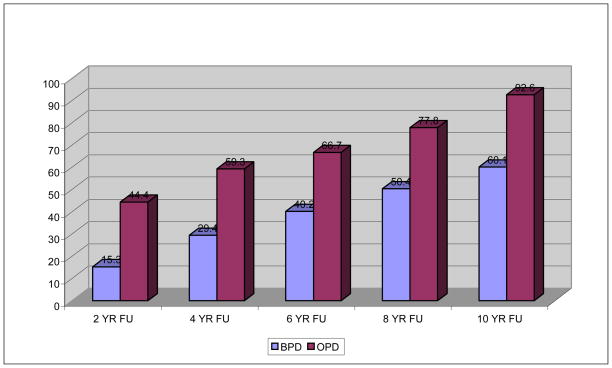

Figure 1 presents the percentages of those in both study groups who did not have good psychosocial functioning in the two years prior to their index admission who attained good psychosocial functioning over time. It also presents time-to-attainment of this outcome over a decade of prospective follow-up. As can be seen, about 60% of borderline patients and 93% of axis II comparison subjects without good psychosocial functioning at baseline attained this outcome over time. As can also be seen, borderline patients were significantly less likely than axis II comparison subjects to attain good psychosocial functioning and to attain this outcome significantly more slowly than axis II comparison subjects (HR=0.34, 95%CI=0.20–0.57, z=−3.98, p<0.001). It should be noted that only 2.4% (N=2) of the 82 borderline patients who failed to achieve good psychosocial functioning over the years of follow-up did so because they did not have even one emotionally sustaining relationship.

Figure 1.

Time-to-attainment of Good Psychosocial Functioning for Those Without Such Fucntioning Prior to Their Index Admission

It should also be noted that 93.9% (N=77) of the borderline patients who failed to achieve this outcome did so because they did not have a good vocational record. And 3.7% (N=3) did not attain either aspect of our definition of good psychosocial functioning. Similar figures were found for the three axis II comparison subjects who failed to achieve this outcome: none had only social failure, two had only vocational failure, and one had failure in both the social and vocational realms.

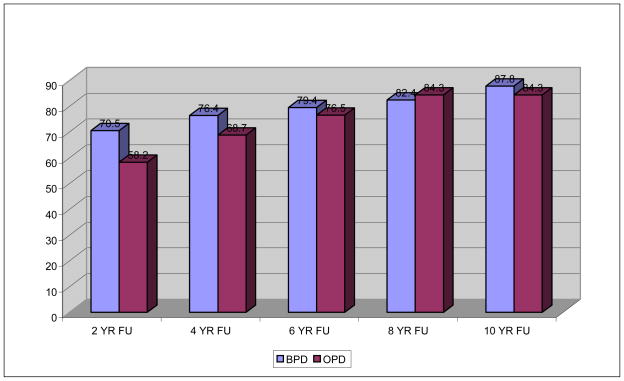

Figure 2 presents the percentage of those in both study groups who had good psychosocial functioning in the two years prior to their index admission who lost the capacity to function well psychosocially over the decade of follow-up. It also presents time-to-loss of this outcome over five waves of follow-up. As can be seen, over 80% of those in both study groups who initially functioned well lost the capacity to function effectively in the psychosocial realm over the ten years of follow-up. As can also be seem, over half of these losses in both diagnostic groups occurred in the first two years of follow-up. In fact, only an additional 17% of borderline patients and an additional 26% of axis II comparison subjects who initially functioned well lost this level of functioning over the next eight years of follow-up. All told, there was no between-group difference in the rate or speed of this outcome (HR=1.17, 95%CI=0.63–2.19, z=−0.49, p=0.623).

Figure 2.

Time-to-Loss of Good Psychosocial Functioning for Those Who First Attained It Prior to Index Admission

It should be noted that 3.4% (N=2) of 58 borderline patients who lost their initially high level of psychosocial functioning lost only their social functioning, 77.6% (N=45) lost only their vocational functioning, and 19% (N=11) lost both. A somewhat similar pattern was found for axis II comparison subjects. More specifically, 15.2% (N=5) of 33 initially high functioning axis II comparison subjects lost only their social functioning, 81.8% (N=27) lost only their vocational functioning, and one (3%) lost both social and vocational functioning.

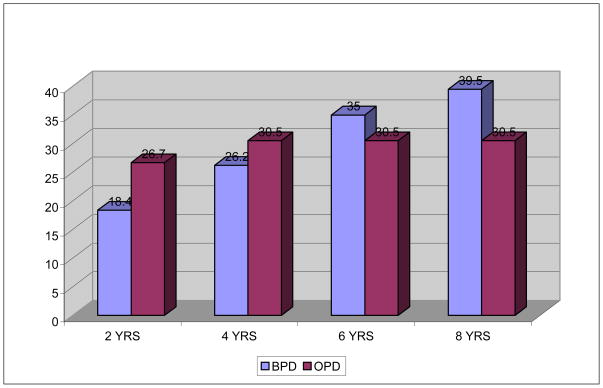

Figure 3 details the percentages of those in both study groups who regained their capacity to function well psychosocially after losing their initially good psychosocial functioning. As can be seen, about 40% of these borderline patients and about 30% of these axis II comparison subjects regained their ability to function well psychosocially. As can also be seen, the percentages of borderline patients who regained their psychosocial functioning continued over the years of follow-up: 18% within two years of losing this level of functioning, 26% within four years, 35% within eight years, and, as noted above, about 40% within 10 years. In contrast, all of axis II comparison subjects regaining good psychosocial functioning did so either within two (27%) or four years of losing this level of functioning (31%). All told, there was no between-group difference in the rate or speed of this outcome (HR=1.17, 95%CI=0.49–2.75, z=−0.35, p=0.723).

Figure 3.

Time-to-reattainment of Good Psychosocial Functioning for Those Who First Attained it Prior to Index Admission

Seventeen borderline patients and 13 axis II comparison subjects who originally had good psychosocial functioning and then lost this level of functioning, did not recover or regain good psychosocial functioning. Of these 17 patients with BPD, one functioned poorly in the social realm, 11 functioned poorly in the vocational realm, and five functioned poorly in both realms. Of the 13 axis II comparison subjects, one functioned poorly in the social realm, 11 functioned poorly in the vocational realm, and one functioned poorly in both realms.

All of the figures presented above for both study groups would be quite different if we had defined good psychosocial functioning as including part-time work or school (rather than full-time vocational engagement). With only this one change to our definition, 82% of borderline patients and 94% of axis II comparison subjects (rather than 60% and 93%) who did not have good psychosocial functioning in the two years prior to their index admission achieved this outcome over the years of follow-up. In a similar vein, 68% of borderline patients and 60% of axis II comparison subjects (rather than 88% and 84%) who did have good psychosocial functioning at baseline lost it over time. Finally, 81% of borderline patients and 71% of axis II comparison subjects (rather than 40% and 30%) who lost their initially good psychosocial functioning regained it over time.

Discussion

The results of this study reveal three main findings. The first is that only 60% of borderline patients but 93% of axis II comparison subjects who did not function well psychosocially in the two years prior to their index admission achieved good psychosocial functioning in the 10 years of prospective follow-up. Clearly, this outcome was substantially more common among axis II comparison subjects than borderline patients. This outcome was also achieved substantially more rapidly by axis II comparison subjects than borderline patients. In fact, a higher percentage of axis II comparison subjects achieved good psychosocial functioning by the time of the six-year follow-up than borderline patients did over a decade of follow-up.

In addition, it is clear that the difficulty experienced by borderline patients in achieving our multifaceted definition of good psychosocial functioning was due primarily to a failure in the vocational (and not the social) realm. In fact, 98% of the borderline patients who did not have good psychosocial functioning at baseline and who did not attain it over the decade of follow-up failed to do so because they never were able to function well and in a sustained manner at a full-time job or academic program.

It might be argued that our definition of good psychosocial functioning is too rigorous but this definition is consistent with the lay definition of this outcome. In fact, it could be argued that our definition of good psychosocial functioning was too broad and should have required both an emotionally sustaining relationship with a spouse or romantic partner and a close friend. We considered this definition but decided against it because many of our subjects, particularly during the first three waves of follow-up, had not yet reached the average age for a man or women in the US to settle down with a partner (14).

The second main finding is that over 80% of the borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects who had functioned well psychosocially during the two years prior to their index admission lost this level of psychosocial functioning over the decade of follow-up. It should be noted that most of this loss of functioning, particularly for borderline patients, occurred in the first two years of follow-up. It should also be noted that social functioning was far more stable among those in both groups than their vocational functioning.

This loss of initially good psychosocial functioning is consistent with clinical experience in that many patients with BPD suffer a decrement in their psychosocial functioning after being hospitalized for psychiatric reasons. The fact that 97% of these loses were either fully (78%) or partially (19%) explained by a loss of vocational functioning is also consistent with clinical experience.

The third main finding is that only a minority of those in both study groups who initially had good psychosocial functioning and then lost it, regained it over the years of follow-up. More specifically, about 40% of once high functioning borderline patients and 30% of once high functioning axis II comparison subjects regained this level of psychosocial functioning. These figures are disheartening but not surprising as it is difficult to regain good psychosocial functioning after a period of not accommodating to the demands of full-time work or school. These individuals might have become more demoralized than they were initially, become habituated to a less stressful life, or both.

It is not clear what interferes with the psychosocial functioning of borderline patients, particularly in the vocational realm. It might be symptoms of BPD. It might also be co-occurring axis I disorders. Or it might be something temperamental in nature. This temperamental aspect, in turn, could be something specific to BPD or something shared by many people who have trouble achieving and maintaining good social and/or vocational functioning. In addition, this dysfunction could be related to the process of aging. A report from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study (CLPS) has found that the psychosocial functioning of borderline patients who were in their mid 30s and 40s at baseline improves over the first three years of prospective follow-up but starts to decline in latter half of the six years they were followed (15).

Of course, this difficulty functioning psychosocially, particularly in the vocational realm, does not occur in a vacuum. Rather, those in the patient’s support system might feel that he or she is suffering too much to work at a full-time job or any job. In these cases, federal disability benefits are often seen as a way to give someone a modest income and a time out from the stress of working or going to school. In other cases, the attendant Medicare and/or Medicaid that often comes with being on federal disability is seen as a way to fund ongoing psychiatric treatment. Or both reasons might be motivating factors in encouraging someone with BPD to apply for disability benefits.

Taken together, the results of this study have implications for DSM-V. Each of the three published iterations of the DSM system that included BPD suggested that it is a chronic disorder (16–18). And yet, the results of both MSAD and CLPS suggest that symptomatic remissions are common and recurrences are relatively rare (13,19–21). In response this symptomatic picture, Skodol et al. (6) have suggested that it is the psychosocial functioning of borderline patients that is chronically impaired. And yet, fully 60% of the borderline patients in the current study who did not have good psychosocial functioning prior to their index admission did attain this outcome over a decade of follow-up. Perhaps it is more accurate to describe BPD as a slow moving or slowly evolving disorder rather than one marked by a lack of change in either the symptomatic or psychosocial realms. Additionally, difficulty with psychosocial functioning is not specific to BPD and in fact, is common among even those with so-called episodic disorders, such as major depression (22) and bipolar disorder (23).

The results of this study also have treatment implications. We have previously noted that all of the manualized treatments for BPD focus on lessening the severity of the acute symptoms of BPD (e.g., self-mutilation, help-seeking suicide efforts) rather than trying to ameliorate the temperamental symptoms of BPD that are more strongly associated with psychosocial impairment (e.g., intolerance of aloneness, undue dependency) (24). It is equally true that it is a rare clinician or treatment program that makes improving the psychosocial functioning of borderline patients a primary or even secondary focus of treatment. And yet, this may be what some borderline patients need.

This study has a number of limitations. The first is that all subjects were initially inpatients. It may well be that borderline patients who have never been hospitalized have better psychosocial functioning than those who have been hospitalized. The second is that the subjects provided all of the information pertaining to their psychosocial functioning. Whether they were accurate historians, were exaggerating their histories, or minimizing them is unknown. However, their responses at four-year follow-up were found to be very similar to those of an informant (5). The third is that the majority of the sample was in treatment prior to their index admission and over time and thus, the results may not generalize to untreated subjects. More specifically, about 90% of those in both patient groups were in individual therapy and taking psychotropic medications at baseline and about 70% were participating in each of these outpatient modalities during each follow-up period (25).

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that good psychosocial functioning that involves both social and vocational competence is difficult for borderline patients to achieve and maintain over time. They also suggest that vocational functioning is substantially more compromised than social functioning.

Significant Outcomes.

At baseline, 25.9% of borderline patients and 58.3% of axis II comparison subjects had had good social and vocational functioning in the two years prior to their index admission.

About 60% of borderline patients and 93% of axis II comparison subjects who did not have good psychosocial functioning at baseline achieved this outcome by the time of the 10-year follow-up.

In addition, over 80% of those in both study groups who were high functioning psychosocially prior to their index admission lost this level of functioning over the decade of follow-up.

However, only 40% of borderline patients and 30% of axis II comparison subjects who lost this level of functioning regained it over the years of follow-up.

Limitations.

The subjects provided all of the information pertaining to their psychosocial functioning.

All subjects were initially inpatients and thus, the results of this study may not apply to less seriously ill outpatients.

The majority of the sample was in treatment and thus, the results may not generalize to untreated subjects.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169.

References

- 1.McGlashan TH. The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study. III. Long-term outcome of borderline personalities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:20–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800010022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paris J, Brown R, Nowlis D. Long-term follow-up of borderline patients in a general hospital. Compr Psychiatry. 1987;28:530–536. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plakun EM, Burkhardt PE, Muller JP. 14-year follow-up of borderline and schizotypal personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 1985;26:448–455. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(85)90081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone MH. The Fate of Borderline Patients. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Hennen J, Silk KR. Psychosocial functioning of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. J Personal Disord. 2005;19:19–29. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.1.19.62178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, Shea MT, Gunderson JG, Yen S, Stout RL, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH. Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychol Med. 2005;35:443–51. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400354x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zanarini MC. Background Information Schedule. McLean Hospital; Belmont, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rational, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. J Personal Disord. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL, Gunderson JG. The Diagnostic Interview for Personality Disorders: inter-rater and test-retest reliability. Compr Psychiatry. 1987;28:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(87)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Vujanovic AA. The inter-rater and test-retest reliability of the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R) J Personal Disord. 2002;16:270–276. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.3.270.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. The longitudinal course of borderline psychopathology: 6-year prospective follow-up of the phenomenology of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:274–283. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. 2008. America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea MT, Edelen MO, Pinto A, Yen S, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Markowitz J, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Ansell E, Daversa MT, Zanarini MC, McGlashan TH, Morey LC. Improvement in borderline personality disorder in relationship to age. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shea MT, Stout RL, Gunderson JG, Morey LC, Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE, Dolan-Sewell R, Dyck I, Zanarini MC, Keller MB. Short-term diagnostic stability of schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2036–2041. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Gunderson JG, Pagano ME, Yen S, Zanarini MC, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Morey LC, McGlashan TH. Two-year stability and change in schizotypal, borderline, avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:767–775. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Silk KR. Prediction of the10-year course of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:827–832. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, Paulus M, Leon AC, Maser JD, Endicott J, Coryell W, Kunovac JL, Mueller TI, Rice JP, Keller MB. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:375–380. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tohen M, Zarate CA, Hennen J, Khalsa HM, Strakowski SM, Gebre-Medhin P, Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ. The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2099–2107. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Silk KR, Hudson JI, McSweeney LB. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:929–935. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Silk KR. Mental health service utilization of borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects followed prospectively for six years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:28–36. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]