Abstract

Adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs) constitutively produce the salt-retaining hormone aldosterone and are a common cause of severe hypertension. Recurrent mutations in the potassium channel KCNJ5 that result in cell depolarization and Ca2+ influx cause ~40% of these tumors1. We found five somatic mutations (four altering glycine 403, one altering isoleucine 770) in CACNA1D, encoding a voltage-gated calcium channel, among 43 non-KCNJ5-mutant APAs. These mutations lie in S6 segments that line the channel pore. Both result in channel activation at less depolarized potentials, and glycine 403 mutations also impair channel inactivation. These effects are inferred to cause increased Ca2+ influx, the sufficient stimulus for aldosterone production and cell proliferation in adrenal glomerulosa2. Remarkably, we identified de novo mutations at the identical positions in two children with a previously undescribed syndrome featuring primary aldosteronism and neuromuscular abnormalities. These findings implicate gain of function Ca2+ channel mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism.

Aldosterone is normally produced in response to volume depletion (via angiotensin II signaling) or hyperkalemia2. Aldosterone signaling defends intravascular volume by increasing intestinal and renal Na-Cl absorption and reabsorption, respectively. Constitutive production of aldosterone (primary aldosteronism) results in hypertension, often associated with hypokalemia3. About 5% of patients referred to hypertension clinics (1 to 10 million people world-wide) have aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs)3,4. APAs are typically benign, well-circumscribed and solitary; their removal cures or ameliorates hypertension. KCNJ5 mutations alter channel selectivity, allowing Na+ conductance. This results in cell depolarization, activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, aldosterone production and cell proliferation. These mutations are inferred to be sufficient for APA formation because rare patients with Mendelian aldosteronism and massive adrenal hyperplasia have identical KCNJ5 mutations in their germline1,5.

We performed exome sequencing of 14 APAs and matched germline DNA. All patients had hypertension with elevated aldosterone levels despite suppressed plasma renin activity (PRA) and a pathologic diagnosis of APA (Supplementary Table 1). Four previously sequenced APAs1 were added to subsequent analysis (total 18 APAs). Samples were sequenced to high coverage and somatic mutations were called (Online Methods, Supplementary Table 2). The mean somatic mutation rate was 3.0 × 10−7 per base, with a mean of 1.7 silent and 6.1 protein-altering somatic mutations per tumor (median 1 and 3.5, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 1). Five of these 18 APAs had disease-causing mutations in KCNJ5 (p.Gly151Arg or p.Leu168Arg), and one had a known gain of function mutation, CTNNB1 (p.Ser45Phe), previously found in adrenocortical tumors6.

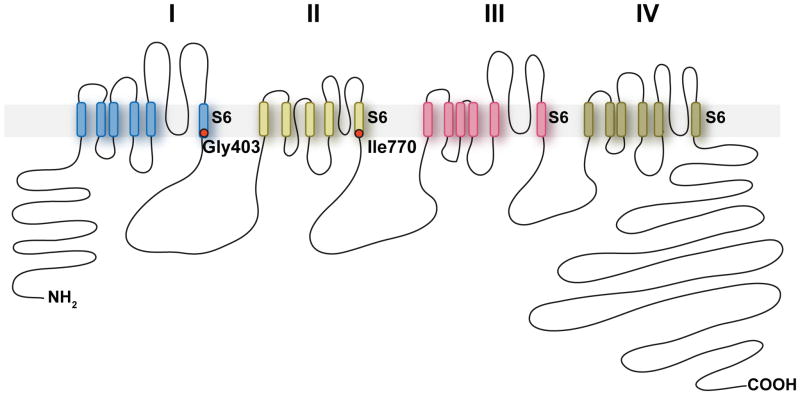

One gene, CACNA1D, had somatic mutations in more than one APA (missense mutations p.Gly403Arg (NM_001128840.2:c.1207G>C) and p.Ile770Met (NM_000720.3:c.2310C>G; and in different isoform NM_001128840.2:c.2250C>G)), both in tumors without KCNJ5 or CTNNB1 mutations) (Fig. 1). Both mutations are previously undescribed (absent among >10,000 exomes in public and Yale databases), apparently heterozygous, and confirmed by direct Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1a). Both occurred in tumors with few protein-altering somatic mutations (4 and 2, respectively) (Supplementary Table 3) and zero detected copy number variants (CNVs). CACNA1D encodes CaV1.3, the α1 (pore-forming) subunit of an L-type (long-lasting) voltage-gated calcium channel. These α1 subunits contain 4 repeated domains (I-IV) (Fig. 2), each with 6 transmembrane segments (S1-S6) and a membrane-associated loop between S5 and S6. S5, S6 and the interposed loop line the channel pore7. The two CACNA1D mutations occur in similar positions near the cytoplasmic ends of S6 segments of domains I and II (Fig. 1c, Fig. 2).

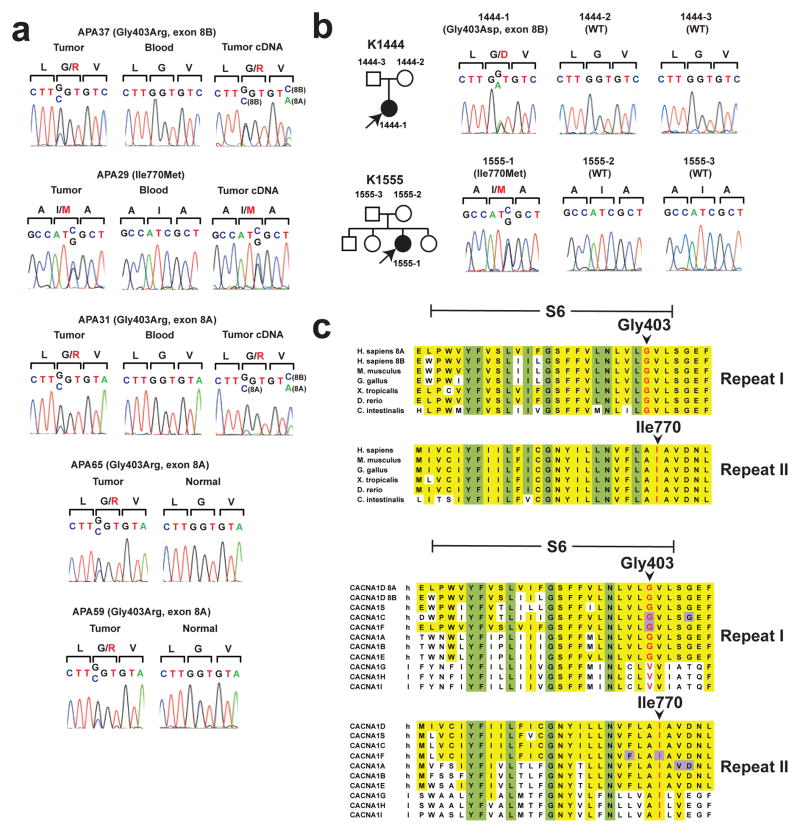

Figure 1.

CACNA1D mutations in aldosterone-producing adenomas and primary aldosteronism. (a) Sequences of tumor and blood genomic DNA, and (where available) tumor cDNA, of CACNA1D codons 402–404 in APA37, APA31, APA65 and APA59, and of codons 769–771 in APA29. Mutations are present in tumor only, and expressed in cDNA. Sequencing the products of cloned PCR products confirmed the presence of identified mutations in APAs 31, 65 and 59. (b) Pedigrees of kindreds with germline CACNA1D mutations. Affected individuals are shown as filled symbols. The corresponding Sanger sequences are depicted to the right. (c) Conservation of Gly403 and Ile770 in orthologs and paralogs. S6, S6 segment; ‘h’, high-voltage activated; ‘l’, low-voltage activated. Residues conserved among all homologs are marked in yellow, and positions conserved in ≥90% of all homologs in both repeats are marked in green. Residues associated with known gain of function mutations in human diseases14–17,22 are marked in purple.

Figure 2.

Transmembrane structure of CaV1.3. CACNA1D encodes the pore-forming α1 subunit of a voltage-gated calcium channel. These channels feature four homologous repeats (I–IV) with 6 transmembrane segments (S1-S6) and a membrane-associated loop between segments S5 and S6. The five APA and two germline CACNA1D mutations identified in this study are located at the end of S6 segments implicated in channel gating.

Direct Sanger sequencing of all the S6 segments in CACNA1D in 46 additional APAs, including highly similar alternative splice isoforms of the first S6 segment (encoded by alternative exons 8A and 8B8) identified three additional somatic mutations in these segments. Most interestingly, two were the same Gly403Arg mutation in exon 8A found by exome sequencing, and one produced the homologous Gly403Arg mutation in exon 8B. Further sequencing identified 16 additional tumors with Gly151Arg or Leu168Arg mutations in KCNJ5 and one additional CTNN1B mutation (p.Ser45Pro). All CACNA1D mutations occurred in tumors without KCNJ5 or CTNN1B mutations. Collectively, CACNA1D mutations were identified in 5 of 64 APAs (7.8%), including 5/41 without KCNJ5 or CTNNB1 mutations (12.2%). The probability of finding the identical somatic mutation at any base in the exome 3 times by chance among 64 tumors, given the observed somatic mutation rate, is 3.0 × 10−8; including the tumor with somatic mutation at the homologous base in exon 8B, the probability of seeing either of these mutations in 4 of 64 tumors is 2.2 × 10−12 (Online Methods).

Gly403 and Ile770 are completely conserved in orthologs from invertebrates to humans (Fig. 1c). Additionally, Ile770 is conserved in all paralogs (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, Gly403 is conserved among all paralogs that are activated by large depolarizing potentials (high-voltage-activated), but not among channels activated by small changes in membrane potential (low-voltage-activated) (Fig. 1c). The finding of recurrent and clustered somatic CACNA1D mutations strongly suggests a gain of function mechanism.

While CACNA1H (CaV3.2) has been implicated in cyclic glomerulosa cell membrane potential oscillations and aldosterone secretion9, little is known about the role of CACNA1D (CaV1.3). Wild-type and mutant CACNA1D alleles are expressed in tumor cDNA (Fig. 1a). Moreover, analysis of normal human adrenocortical RNA1 revealed that CACNA1D was the most highly expressed Ca2+ channel subunit, followed by β2 (CACNB2) and α2δ1 (CACNA2D1) subunits (Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, immunohistochemistry with 3 anti-CACNA1D (CaV1.3) antibodies demonstrated expression in human zona glomerulosa (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings support a role for CaV1.3 in normal adrenal cortex and APA.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry of CaV1.3 in human adrenal gland. Human adrenal gland was stained with anti-CaV1.3 (Sigma) (a,c) or anti-Dab2 (b,d, an adrenal glomerulosa marker), and sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. CaV1.3 is expressed in adrenal glomerulosa. (a,b), scale bar represents 500 μm; (c,d), 100 μm. C, capsule; G, glomerulosa; F, fasciculata; R, reticularis.

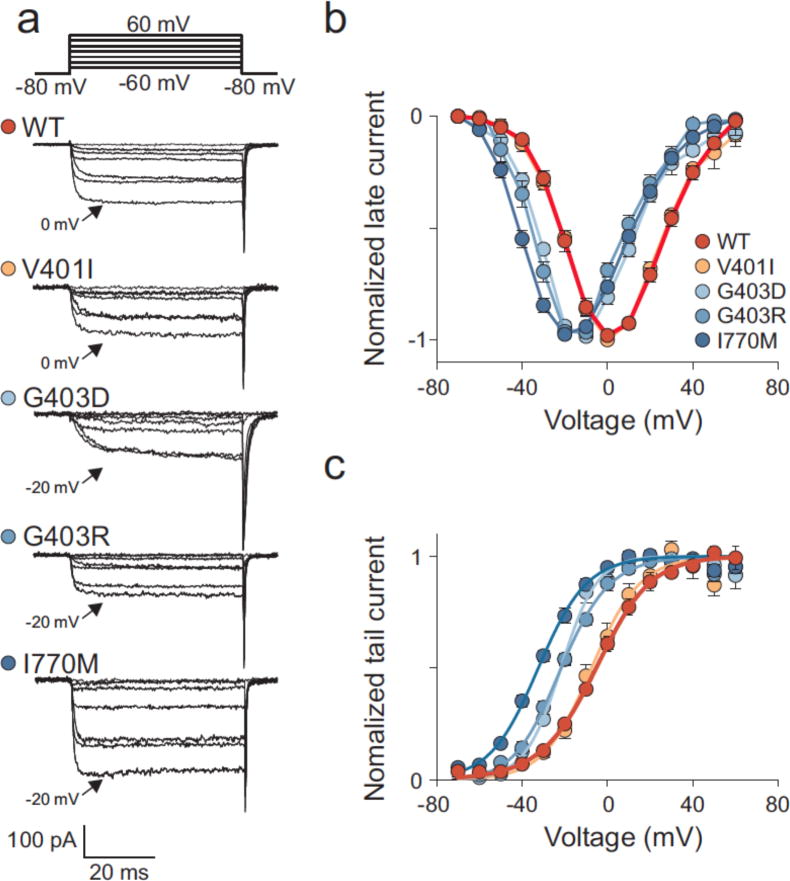

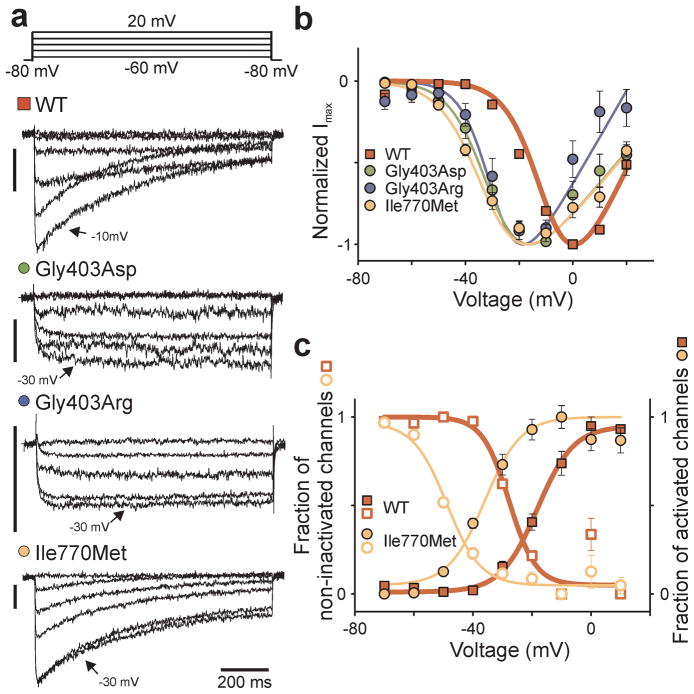

To assess the effect of CACNA1D mutations on channel function, we expressed wildtype (WT) and mutant CaV1.3 together with β2 (β2a isoform) and α2δ1 subunits in HEK293T cells. Figure 4a shows representative whole-cell patch clamp recordings. Upon depolarizing voltage steps, CaV1.3WT calcium currents showed fast activation, followed by a slow decay caused by voltage-dependent (VDI) and calcium-dependent inactivation (CDI)10 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Compared to WT channels, the Gly403Arg mutant (CaV1.3G403R) and Ile770Met mutant (CaV1.3I770M) both showed maximum current amplitudes at less depolarized potentials (Fig. 4b). CaV1.3WT exhibited a half-maximal activation voltage (V½) at −9.2 ± 1.0 mV (s.e.m., n = 7), while V½ for CaV1.3G403R and CaV1.3I770M was −25.6 ± 2.5 mV (n = 7, P < 0.001 versus WT) and −31.7 ± 1.1 mV (n = 6, P < 0.001 versus WT) respectively, indicating that these mutations facilitated channel opening (Fig. 4b). Current densities are shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Figure 4.

CaV1.3 mutations shift the voltage-dependence of activation to more hyperpolarized potentials. (a) Representative whole cell recordings of HEK293T cells transiently expressing WT or mutant CaV1.3 together with β2a and α2δ1 subunits (vertical bar: 50 pA). Currents were elicited by voltage pulses between −60 mV and +20 mV including the peak current amplitude (arrow). (b) Voltage dependence of normalized peak current amplitudes (Imax) of WT (n = 7), Gly403Asp (n = 5), Gly403Arg (n = 7) or Ile770Met (n = 6) channels. The voltage dependence of activation is shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials in Gly403Asp, Gly403Arg and Ile770Met channels. (c) Activation (filled symbols) and inactivation (open symbols) curves of WT and Ile770Met channels. Activation and inactivation of Ile770Met channels are both shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials. Activation curves were calculated from b, while the inactivation curves were calculated from fits of the inactivation time courses. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

The Gly403Arg mutation also drastically impaired inactivation of Cav1.3WT (Fig. 4a), suggesting a role for sustained activation with this mutation. CaV1.3I770M showed inactivation shifted to more hyperpolarized potentials (Fig. 4a, 4c, Supplementary Fig. 3).

By analogy to KCNJ5, we considered possible germline CACNA1D mutations. We sequenced CACNA1D S6 segments of domains I and II in 100 unrelated subjects with unexplained early-onset primary aldosteronism. Remarkably, we found mutations altering the same amino acids mutated in APAs in 2 subjects – one (1441-1) with a Gly403Asp mutation in exon 8B, and another (1555-1) with the Ile770Met mutation (Fig. 1b). Neither has been seen previously in SNP or exome databases. Both were de novo mutations as they were absent in their parents, with genotyping of nine highly polymorphic short tandem repeat markers providing unequivocal evidence of maternity/paternity (Supplementary Table 5). The probability of finding by chance two de novo mutations in any of the 3 CACNA1D codons mutated in APAs among 100 test cases is 3.8 × 10−11 (Online Methods), implicating these de novo mutations in disease pathogenesis. Electrophysiology of the germline p.Gly403Asp mutation (CaV1.3G403D) in subject 1444-1 demonstrated activation at less depolarizing potentials (V1/2 = −32.4 ± 2.3 mV (n = 5, P < 0.001 versus WT)) and markedly impaired inactivation – similar to Gly403Arg (Fig. 4).

Subject 1444-1 was diagnosed with hypertension at birth (blood pressure 119/78 mmHg; >99th percentile) with biventricular hypertrophy, a ventricular septal defect, pulmonary hypertension, and second-degree heart block. Aldosterone was elevated (128.6 ng/dL) with low plasma renin activity (PRA, 0.78 ng/ml/h) and high aldosterone:renin ratio (ARR, 165, >30 consistent with primary aldosteronism). The clinical course was notable for uncontrolled hypertension with hypokalemia (serum K+ 3.3 mmol/L, normal 3.5–5.6). Interestingly, treatment with a calcium channel blocker, amlodipine, normalized blood pressure, and biventricular hypertrophy resolved. Other features included a seizure disorder, apparent cerebral palsy, cortical blindness, and complex neuromuscular abnormalities. There was no significant family history (Supplementary Note).

Subject 1555-1 was diagnosed at birth with cerebral palsy, spastic quadriplegia, mild athetosis, severe generalized intellectual disability, and complex partial and generalized seizures. At age 5 years, she was markedly hypertensive (132/90 mmHg; >99th percentile), with retrospective recognition of persistently elevated blood pressure and polydipsia. She had hypokalemia (serum K+ 2.8 mmol/L) and metabolic alkalosis (bicarbonate 30 mmol/L). Serum aldosterone was high (36 ng/dL), despite suppressed PRA (0.15 ng/mL/h; ARR 240). CT scan showed no adrenal abnormality, and echocardiogram showed mild left ventricular hypertrophy. She was treated with clonidine, and later spironolactone. There was no significant family history (Supplementary Note).

These results implicate recurrent gain of function mutations in CACNA1D in ~8% of APAs and a new Mendelian syndrome featuring primary aldosteronism associated with seizures and neuromuscular disease. The finding of de novo germline mutations at the same positions as somatic mutations found in APAs is consistent with these single mutations being sufficient for production of APA, analogous to findings with KCNJ51. These findings indicate that APAs are commonly caused by single mutations and have implications for other hormone-producing tumors. Moreover, they underscore the discovery of novel biology in a range of benign tumors1,11.

Electrophysiological studies of mutant CaV1.3 channels implicate increased Ca2+ influx in disease pathogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 5). Mutant channels activate at membrane potentials closer to the glomerulosa resting potential (about −82 mV9); moreover, inactivation of CaV1.3G403R and CaV1.3G403D is impaired. Spontaneous glomerulosa membrane potential oscillations9 may contribute to activation of these mutant channels. While increased current densities were seen with CaV1.3I770M and CaV1.3G403D, this was not the case for CaV1.3G403R (Supplementary Fig. 4). Because high Ca2+ influx may increase cell lethality, one must interpret differences in current density with caution. Further studies of the properties of single channels and the impact of these mutations in engineered animal models will be of interest.

Increased Ca2+ influx due to CACNA1D mutations phenocopies the consequence of KCNJ5 mutations, which cause increased Ca2+ influx by depolarizing glomerulosa cells. This suggests increased intracellular Ca2+ as a final common pathway to APA formation. These findings have implications for other hormone-secreting tumors and endocrinopathies in which hormone secretion is regulated by Ca2+.

While the mutations described herein are gain of function, homozygous loss of function mutations in CACNA1D in mice and humans result in deafness, bradycardia and arrhythmia8,12.

Interestingly, mutations in S6 segments of other L-type Ca2+ channels cause disease by similar gain of function effects13. Germline mutations altering the positions homologous to Gly403 and Ile770 in CACNA1F cause congenital stationary night blindness type 214,15; similarly, mutation at the position homologous to Gly403 in CACNA1C causes Timothy syndrome16 (Fig. 1c). Finally, gain of function mutations in S6 segments of CACNA1A cause familial hemiplegic migraine17,18.

While only a small number of APAs with CACNA1D mutations have been identified, tumors with CACNA1D mutations were significantly smaller than those with KCNJ5 mutations (13.4 ± 4.8 mm versus 21.9 ± 7.4 mm, s.d., P = 0.01), and there was a trend toward older age at presentation (53.8 ± 9.0 versus 43.6 ± 10.7 years, P = 0.06). Unlike KCNJ5 mutations1,19, CACNA1D mutations did not show a strong female bias (3/30 males, 2/34 females).

The subjects with de novo activating CACNA1D mutations represent a previously undescribed Mendelian syndrome featuring primary aldosteronism. While additional cases will be required to fully define the extraadrenal manifestations of this syndrome, their complicated neuromuscular histories indicate a multisystem disease, consistent with CACNA1D expression in neurons and heart8. The absence of adrenal hyperplasia by CT scan in subject 1555-1 at age 9 is noteworthy. Different germline mutations at the identical position in KCNJ5 are associated with aldosteronism with or without adrenal hyperplasia owing to variable Na+ conductance resulting in varying cell lethality – patients with mutations causing high cell lethality never develop adrenal hyperplasia5. Further work will be required to establish whether the absence of hyperplasia with germline CACNA1D mutation relates to high cell lethality.

Following submission of this paper, recurrent mutations in ATP1A1 (the α subunit of the Na+/K+ ATPase) and ATP2B3 (a plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase) that account for 5.2% and 1.6% of APAs, respectively, were reported20. We sequenced these positions in our cohort and found described mutations in 3 subjects (4.7%, Supplementary Table 1).

Lastly, the apparent response to treatment with a calcium channel blocker in subject 1444-1 raises the possibility of specific treatment for patients with APAs and CACNA1D mutations. Approved calcium channel blockers are weak antagonists of wildtype CaV1.3 although potent and specific CaV1.3 inhibitors have been identified21. Such compounds, or others that are selective for recurrent mutations, may have particular promise in the treatment of a subset of patients with CACNA1D mutations.

Online Methods

Subjects

Matched APA and venous blood DNAs were obtained from patients undergoing adrenalectomy for hypertension with primary aldosteronism and adrenocortical tumor at Yale New Haven Hospital, Uppsala University Hospital, and Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and were evaluated as previously described1. Additional APAs and matched normal samples were obtained from paraffin-embedded samples in Yale Department of Pathology. Additionally, patients with unexplained early onset aldosteronism, including parents in selected cases, were also studied. The research protocols were approved by local IRBs and informed consent was obtained from all research participants.

DNA preparation, genotyping and exome sequencing

Genomic DNA was prepared from venous blood, tumor and surrounding normal tissue by standard procedures. For FFPE samples, DNA was prepared using the QiaAmp DNA FFPE tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Targeted capture of exome sequences was performed using the 2.1M NimbleGen Exome reagent followed by sequencing on the Illumina platform as previously described1. Somatic mutations were called based on the significance of differences in read distributions between matched tumor and blood samples1. Calls were further evaluated by manual inspection of the read alignments. The somatic mutation rate was calculated from the observed number of somatic mutations and the number of coding bases in the exome capture.

Tumor purity was calculated from the mean minor allele frequency (MAF) of all high quality SNPs in regions of LOH. For tumors with no detectable region of LOH, purity was estimated from mean MAF of inferred heterozygous somatic variants.

Copy number variants were called from the normalized ratio of coverage depth comparing tumor and normal samples, and changes in MAF at informative SNPs.

Statistical tests

Two-tailed t-tests were used for statistical analysis of tumor characteristics. P-values for the occurrence of observed mutations by chance were calculated as binomial probabilities from the number of occurrences of specific mutations, the number of tumors studied, the observed somatic mutation rate, and the total number of exonic bases. For statistical analysis of the voltage dependence of activation in WT and mutant channels, V1/2 values were tested for equality of variances and normality (Shapiro-Wilk method) and compared using pairwise multiple comparison procedures (Holm-Sidak method).

Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA

Direct bidirectional Sanger sequencing of CACNA1D from genomic DNA in tumor-blood pairs was performed following PCR amplification using specific primers. All S6 segments of CACNA1D were sequenced in all APAs; the S6 segments of domains I and II were sequenced for germline mutations in patients with early-onset hypertension. Positions with recurrent mutations in KCNJ5, CTNNB1, ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 were sequenced in APAs following amplification by PCR using specific primers. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Genotyping of parent-offspring trios

Nine highly polymorphic markers (loci CSF1PO, D135317, D16S539, D18S51, D7S820, D8S1179, TH01, TPOX, and D195433) were genotyped in parent-offspring trios of kindreds 1444 and 1555 by PCR amplification using specific primers followed by direct Sanger sequencing. Genotypes were scored by the number of repeats present on each allele as independently assessed by two investigators; genotype calls were concordant for all markers. Paternity and maternity indices were separately calculated for each putative parent23 using allele frequencies determined in 258 African Americans or 302 individuals of European descent24.

TOPO cloning of PCR products

DNA was amplified using the G403R_F and G403R_R primers, and PCR products were cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA from individual colonies was amplified by PCR and Sanger sequenced using the G403R_F primer.

cDNA synthesis and sequencing

Total RNA was prepared from fresh-frozen tissue using the AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein Mini Kit (Qiagen) or the TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen), followed by column purification and DNase digestion using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription of 100 ng RNA was performed with Oligo(dT)12-18 priming (Invitrogen) using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). cDNA was amplified using intron-spanning primers G403RTF/R and I770RTF/R and sequenced with forward and reverse primers.

Immunohistochemistry

5 μM sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded normal human adrenal cortex (2 patients) were obtained from the Yale Pathology Tissue Service. Sections were deparaffinized and epitope retrieval was performed by heating in 10 mM sodium citrate in a microwave. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3–3% H2O2, and samples were permeabilized in 1% SDS in TBS or 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. After blocking, slides were incubated with anti-CACNA1D (#HPA020215, Sigma; 1:100 dilution), anti-Dab2 (#sc-13982, Santa Cruz; 1:100 dilution), anti-L-type Ca++ CP α1D (#sc-32071, Santa Cruz, 1:50–1:100 dilution) or anti-CaV1.3 (#ACC-005, Alomone, 1:100–1:250 dilution) for 12 hours. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat secondary antibody and DAB were used to visualize the signal. Where signal was low, a biotinylated secondary antibody was used, followed by HRP streptavidin. For Alomone and Santa Cruz antibodies, immunizing peptides were tested for their ability to block antibody labeling of tissues following manufacturer’s protocols; incubations with and without immunizing peptides were processed in parallel. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. Images were captured using a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 microscope and processed using AxioVision software (Rel. 4.8) and Adobe Photoshop.

Molecular Cloning

The canonical isoform of human CACNA1D in pCMV6-XL6 was obtained from Origene (#SC309716, NM_000720.1). This isoform contains exon 8B. Other isoforms (NM_001128840.2 and NM_001128839.2) have all the same domain structures but vary in the presence of exons 11, 32 and 44 in extracellular and intracellular segments.

Site-directed mutagenesis (Quikchange, Stratagene) was performed to introduce the Gly403Arg, Ile770Met and Gly403Asp mutations into CACNA1D. Each construct was validated by sequencing of the complete coding region. The CaVβ2a coding region (Swiss-Prot accession number Q8VGC3-2) was fused at its carboxy-terminal end to mCherry and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector. The CaVα2δ1 cDNA in the pIRES-dsRed vector was kindly provided by Dr. Frank Lehmann-Horn (University of Ulm, Germany).

Plasmids were prepared using the HiSpeed Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen).

Transient transfection and electrophysiological recordings

HEK293T cells (The European Collection of Cell Cultures) were grown to 80% confluence on 10 cm dishes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin G (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (10 mg/ml) and incubated in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Cells were co-transfected with 1 μg of β2a-mCherry, 1 μg of α2δ1 and 2 μg of CACNA1D WT, Gly403Asp, Gly403Arg, or Ile770Met expression plasmids using Lipofectamine LTX (Life Technologies). Currents were recorded from transfections with plasmids from at least two preparations of each CACNA1D construct. Cells were split 24 h after transfection. Currents were recorded on a HEKA EPC 10 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik) using the Patchmaster software. Borosilicate pipettes with resistances of 1–3 MΩ were pulled on a Sutter P-97 puller (Harvard Apparatus) and fire-polished using a Narishige MF-900 microforge. The extracellular solution contained: 5 mM CaCl2, 125 mM TEA-Cl, 10 mM HEPES, 15 mM Mannitol, pH 7.4. Pipette solution contained: 100 mM CsCl, 5 mM TEA-Cl, 3.6 mM PCr-Na2, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM Mg-ATP, 0.2 mM Na-GTP, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 (titration with CsOH). Currents were elicited by 1–2 s voltage pulses ranging from −70 mV to +20 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −80 mV25. No visible calcium currents were recorded in cells transfected with β2a and α2δ1 subunits alone. Only recordings with distinct currents in the presence of external Ca2+ or Ba2+ that stayed stable over the recording duration were used for analysis.

Data were filtered at 3 kHz. Peak current amplitudes depend on the voltage dependences of the open probability and the unitary current. Since calcium channels exhibit a constant unitary conductance under our experimental conditions, the voltage dependences of activation were obtained by fitting a plot of the current-voltage relation according to:

| (1) |

with I being the macroscopic current, G the maximum conductance, V the voltage, Vrev the reversal potential, V1/2 the half-maximal activation and k the slope. Plots of the relative open probabilities of activation were calculated by dividing peak-current voltage plots by the normalized maximum conductance (Ipeak/(V−Vrev))26 and fitted with the Boltzmann function according to:

| (2) |

with Popen being the open probability at the desired voltage.

The time course of inactivation10 was determined by fitting the current decay after activation with a bi-exponential function:

| (3) |

with A being the amplitude of the individual components, t the time and τ the corresponding time constants. The residual amplitude A0 corresponds to the steady state current at the given potential. The voltage dependence of the ratio of A0 by Ipeak provides the steady-state inactivation curve that was fitted with a Boltzmann function27.

Data were analyzed in FitMaster (HEKA Elektronik) and SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific).

Orthologs and paralogs

Orthologs or close paralogs of CACNA1D in vertebrate and invertebrate species were identified by a BLAST search1. GenBank accession numbers were: NP_001122311.1 (human isoform c), NP_000711.1 (human isoform a), NP_001077085.1 (mouse), NP_990365.1 (chicken), XP_002938148.1 (frog), NP_982351.1 (zebrafish), and XP_002123864.1 (tunicate). For human α1 subunit paralogs, GenBank accession numbers were: NP_000060.2 (CACNA1S), NP_955630.2 (CACNA1C), NP_005174.2 (CACNA1F), NP_000059.3 (CACNA1A), NP_000709.1 (CACNA1B), NP_001192222.1 (CACNA1E), NP_061496.2 (CACNA1G), NP_066921.2 (CACNA1H), and NP_066919.2 (CACNA1I).

Adrenal Cortical Gene Expression

Calcium channel expression in human adrenal cortex was extracted from a previously described dataset1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and families whose participation made this study possible. We thank the staff of the Yale West Campus Genomics Center, the Yale Cellular and Molecular Physiology Microscopy and Imaging Core, the Endocrine Surgical Laboratory, Clinical Research Centre, Uppsala University Hospital and the Department of Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, for their invaluable contributions to this research. Drs. Jan Matthes (Universität Köln, Germany) and Frank Lehmann-Horn (Universität Ulm, Germany) kindly provided us with α2δ subunit clones. Supported by the NIH Centers for Mendelian Genomics (5U54HG006504), the Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Network in Hypertension, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, and the Lions Cancer Fund, Uppsala. GG is supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore. TC is a Doris Duke-Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator. RPL is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Data access.

All somatic mutations found by exome sequencing are deposited in dbSNP under batch accession number 1059250.

Author contributions

ALF, LFS, JWK, MLP, EAH, NM, MRB, TB, JRS, EL, UIS, RPL, SKL, PHe, GW, GÅ, PB and TC ascertained and recruited patients, obtained samples and medical records; ALF, RK, LFS, UIS, PB and CNW prepared DNA and RNA samples and maintained sample archives; JDO and SM performed exome sequencing; UIS and GG performed and analyzed targeted DNA and RNA sequencing; GG, MC and RPL analyzed exome sequencing results; UIS and RK performed immunohistochemistry; UIS, GS, RCO, ChF and PHi made constructs and performed and analyzed electrophysiology; UIS, GG, GS, ChF, PHi and RPL wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Choi M, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1198785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spat A, Hunyady L. Control of aldosterone secretion: a model for convergence in cellular signaling pathways. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:489–539. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi GP, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conn JW. Presidential address. I Painting background II Primary aldosteronism, a new clinical syndrome. J Lab Clin Med. 1955;45:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl UI, et al. Hypertension with or without adrenal hyperplasia due to different inherited mutations in the potassium channel KCNJ5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2533–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121407109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tadjine M, Lampron A, Ouadi L, Bourdeau I. Frequent mutations of beta-catenin gene in sporadic secreting adrenocortical adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:264–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA. Signaling complexes of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Neurosci Lett. 2010;486:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baig SM, et al. Loss of Ca(v)1.3 (CACNA1D) function in a human channelopathy with bradycardia and congenital deafness. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu C, Rusin CG, Tan Z, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ. Zona glomerulosa cells of the mouse adrenal cortex are intrinsic electrical oscillators. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2046–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI61996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tadross MR, Ben Johny M, Yue DT. Molecular endpoints of Ca2+/calmodulin- and voltage-dependent inactivation of Ca(v)1.3 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2010;135:197–215. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark VE, et al. Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO. Science. 2013;339:1077–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1233009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Platzer J, et al. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hering S, et al. Pore stability and gating in voltage-activated calcium channels. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:61–9. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.2.5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoda JC, Zaghetto F, Koschak A, Striessnig J. Congenital stationary night blindness type 2 mutations S229P, G369D, L1068P, and W1440X alter channel gating or functional expression of Ca(v)1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2005;25:252–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3054-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemara-Wahanui A, et al. A CACNA1F mutation identified in an X-linked retinal disorder shifts the voltage dependence of Cav1.4 channel activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7553–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501907102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Splawski I, et al. Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8089–96. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. discussion 8086–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hans M, et al. Functional consequences of mutations in the human alpha1A calcium channel subunit linked to familial hemiplegic migraine. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1610–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-05-01610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Battistini S, et al. A new CACNA1A gene mutation in acetazolamide-responsive familial hemiplegic migraine and ataxia. Neurology. 1999;53:38–43. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholl UI, Lifton RP. New insights into aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary aldosteronism: mutations in the K+ channel KCNJ5. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22:141–7. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835cecf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beuschlein F, et al. Somatic mutations in ATP1A1 and ATP2B3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:440–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang S, et al. Ca(V)1.3-selective L-type calcium channel antagonists as potential new therapeutics for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1146. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peloquin JB, Rehak R, Doering CJ, McRory JE. Functional analysis of congenital stationary night blindness type-2 CACNA1F mutations F742C, G1007R, and R1049W. Neuroscience. 2007;150:335–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner CH. A note on paternity computation in cases lacking a mother. Transfusion (Paris) 1993;33:51–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33193142310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler JM, Schoske R, Vallone PM, Redman JW, Kline MC. Allele frequencies for 15 autosomal STR loci on U.S. Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic populations. J Forensic Sci. 2003;48:908–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Gutierrez G, et al. The guanylate kinase domain of the beta-subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels suffices to modulate gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14198–203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcantoni A, et al. Loss of Cav1.3 channels reveals the critical role of L-type and BK channel coupling in pacemaking mouse adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:491–504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4961-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts-Crowley ML, Rittenhouse AR. Arachidonic acid inhibition of L-type calcium (CaV1.3b) channels varies with accessory CaVbeta subunits. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:387–403. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.