Abstract

Three types of human T-cell leukemia virus (HTLV)-simian T-cell leukemia virus (STLV) (collectively called primate T-cell leukemia viruses [PTLVs]) have been characterized, with evidence for zoonotic origin from primates for HTLV type 1 (HTLV-1) and HTLV-2 in Africa. To assess human exposure to STLVs in western Central Africa, we screened for STLV infection in primates hunted in the rain forests of Cameroon. Blood was obtained from 524 animals representing 18 different species. All the animals were wild caught between 1999 and 2002; 328 animals were sampled as bush meat and 196 were pets. Overall, 59 (11.2%) of the primates had antibodies cross-reacting with HTLV-1 and/or HTLV-2 antigens; HTLV-1 infection was confirmed in 37 animals, HTLV-2 infection was confirmed in 9, dual HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infection was confirmed in 10, and results for 3 animals were indeterminate. Prevalences of infection were significantly lower in pets than in bush meat, 1.5 versus 17.0%, respectively. Discriminatory PCRs identified STLV-1, STLV-3, and STLV-1 and STLV-3 in HTLV-1-, HTLV-2-, and HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-cross-reactive samples, respectively. We identified for the first time STLV-1 sequences in mustached monkeys (Cercopithecus cephus), talapoins (Miopithecus ogouensis), and gorillas (Gorilla gorilla) and confirmed STLV-1 infection in mandrills, African green monkeys, agile mangabeys, and crested mona and greater spot-nosed monkeys. STLV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) and env sequences revealed that the strains belonged to different PTLV-1 subtypes. A high prevalence of PTLV infection was observed among agile mangabeys (Cercocebus agilis); 89% of bush meat was infected with STLV. Cocirculation of STLV-1 and STLV-3 and STLV-1-STLV-3 coinfections were identified among the agile mangabeys. Phylogenetic analyses of partial LTR sequences indicated that the agile mangabey STLV-3 strains were more related to the STLV-3 CTO604 strain isolated from a red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) from Cameroon than to the STLV-3 PH969 strain from an Eritrean baboon or the PPA-F3 strain from a baboon in Senegal. Our study documents for the first time that (i) a substantial proportion of wild-living monkeys in Cameroon is STLV infected, (ii) STLV-1 and STLV-3 cocirculate in the same primate species, (iii) coinfection with STLV-1 and STLV-3 occurs in agile mangabeys, and (iv) humans are exposed to different STLV-1 and STLV-3 subtypes through handling primates as bush meat.

Simian T-cell leukemia viruses (STLVs) are the simian counterparts of human T-cell leukemia viruses (HTLV), and these viruses are collectively called primate T-cell leukemia viruses (PTLVs). HTLVs are separated into two serologically and genetically distinct types, HTLV type 1 (HTLV-1) and HTLV-2, and both types have simian counterparts, STLV-1 and STLV-2 (8, 36, 37). A third type, STLV-3, was isolated from several African nonhuman primates such as hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) from east and west Africa and red-capped mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus) and greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) from Cameroon (22, 23, 35, 39). STLV-1 has been isolated from a wide variety of Old World monkeys in Asia and Africa, including macaques, baboons, African green monkeys, guenons, mangabeys, orangutans, and chimpanzees, whereas STLV-2 has been identified only in captive bonobos (Pan paniscus) from the Democratic Republic of Congo (12, 13, 15, 24, 29, 40). The close relationship between HTLV-1 and STLV-1 suggests a simian origin for HTLV-1. Moreover, phylogenetic analyses of African HTLV-1 and STLV-1 strains revealed that some HTLV-1 strains are more closely related to STLV-1, suggesting the occurrence of multiple cross-species transmissions between primates and humans and also between different primate species (18).

Similar to HTLV, other simian retroviruses such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 are of zoonotic origin, with their closest simian relatives in the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys), respectively (6, 11). First recognized in the early 1980s, HIV-1 has spread to most parts of the world, and today it is estimated that more than 40 million individuals live with HIV infection or AIDS (34). HTLV is less pathogenic than HIV, but HTLV-1 is known to be associated with lymphoma, leukemia (adult T-cell leukemia), and some neurological disorders such as tropical spastic paraparesis (9, 17, 33).

Given that humans come in frequent contact with primates in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the possibility of additional zoonotic transfers of retroviruses from primates has to be considered. Prevalences of HTLV infection are high in Africa, with the highest values in equatorial Africa and more precisely in the tropical forest region (5). In central Africa, prevalences of HTLV-1 infection increase with age, and in rural areas women and pygmies are more frequently infected (4, 21). All these epidemiological observations, together with the phylogenetic relationships between HTLV and STLV, are in favor of zoonotic transmissions. The risk for acquiring such infections is expected to be the highest in individuals who hunt primates and who prepare their meat for consumption, as well as in people who keep primates as pet animals. Therefore, it is important to study the prevalence, diversity, and geographic distribution of these infections in wild primate populations. In a similar way, it was previously shown that humans are exposed to a plethora of simian immunodeficiency viruses in Cameroon (26).

In the present study, we tested wild-caught primates from Cameroon for STLV infection. Cameroon is known to harbor a diverse set of primate species which are extensively hunted for food and trade at various levels (3). Our study indicates that in addition to frequent contamination with simian immunodeficiency virus, a considerable proportion of primate meat sold for consumption is contaminated with STLV-1 and STLV-3. These data also provide an approximation of the magnitude of exposure and the variety of STLVs to which humans are exposed and permit estimation of the prevalences of STLV infection in wild primate populations in Cameroon. In addition, our study further documents coinfection with STLV-1 and STLV-3 in wild primate populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of primate tissue and blood samples.

Blood was obtained from 524 monkeys all wild caught in Cameroon between January 1999 and July 2002. Species were determined by visual inspection according to The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (14) and by use of the taxonomy described by Colin Groves (10). Three hundred twenty-eight animals were sampled as bush meat upon arrival at markets in Yaounde, the capital city, in surrounding villages, or at logging concessions in southeastern Cameroon; the other 196 animals sampled were pets from these same areas. Table 1 summarizes the numbers of each primate species collected. All primate samples were obtained with government approval from the Cameroonian Ministry of Environment and Forestry. The bush meat samples were obtained by employing a strategy specifically designed not to increase the demand for bush meat, i.e., women preparing and preserving the meat for subsequent sale and hunters already involved in the trade were asked for permission to sample blood and tissues from carcasses which were then returned to their owners; animals and bush meat confiscated by the national program against poaching were also sampled. For the bush meat animals, blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Information provided by the owners indicated that most of the animals had died 12 to 72 h prior to sampling. For the pet monkeys, blood was drawn by peripheral venipuncture after the animals were tranquilized with ketamine (10 mg/kg). Plasma and cells were separated on site by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. All samples, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells, plasma, whole blood, and other tissues, were stored at −20°C.

TABLE 1.

Detection of HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-cross-reactive antibodies in primate species in Cameroon

| Species | Common name | No. of pet animals tested | No. of pet animals positive for:

|

No. of bush meat animals tested | No. of bush meat animals positive for:

|

Total no. of animals tested | Total no. of animals positive for:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTLV-1 | HTLV-2 | HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 | Indeterminate HTLV | HTLV-1 | HTLV-2 | HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 | Indeterminate HTLV | HTLV-1 | HTLV-2 | HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 | Indeterminate HTLV | |||||

| Cercocebus agilis | Agile managabey | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 24 | 7 | 10 | 2 | 65 | 24 | 7 | 10 | 2 |

| Cercocebus torquatus | Red-capped mangabey | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lophocebus albigena | Grey-cheeked mangabey | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mandrillus leucophaeus | Drill | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Mandrillas sphinx | Mandrill | 15 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Papio anubis | Olive baboon | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Cercopithecus cephus | Mustached monkey | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 104 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus mona | Mona monkey | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus neglectus | de Brazza's monkey | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus nictitans | Greater spot-nosed monkey | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 118 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus pogonias | Crested mona | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus preussi | Preuss's monkey | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Chlorocebus tantalus | Tantalus monkey | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Miopithecus ogouensis | Gabon talapoin | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Erytrocebus patas | Patas monkey | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Colobus guereza | Mantled guereza | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pan troglodytes | Chimpanzee | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gorilla gorilla | Gorilla | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (%) | 196 | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 328 | 34 (10.3) | 9 (2.7) | 10 (3.0) | 3 (0.9) | 524 | 37 (7.1) | 9 (1.7) | 10 (1.9) | 3 (0.6) | |

Serology.

Plasma or whole blood samples were tested for the presence of HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies by using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the MUREX HTLV-I+II test (Abbott Laboratories, Wiesbaden, Germany), using as antigens synthetic peptides and recombinant proteins representing immunodominant regions of the envelope and transmembrane regions of HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. Samples reactive in the ELISA were retested with a commercially available line immunoassay, INNO-LIA HTLV I/II (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), which discriminates between HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-cross-reactive antibodies. This test configuration includes HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides that are coated as discrete lines on a nylon strip. The antigenicity exhibited by these proteins and peptides is either common to HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 or specific to one of the two viruses to allow confirmation and discrimination in a single assay. Two Gag (p19-I or p19-II and p24-I or p24-II) and two Env (gp46-I or gp46-II and gp21-I or gp21-II) bands are applied as non-type-specific antigens, which are used to confirm the presence of antibodies against HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. The type-specific antigens for HTLV-1 (Gag p19-I and Env gp46-I) and HTLV-2 (Env gp46-II) are applied to differentiate between HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 infections. In addition to these HTLV antigens, control lines are present on each strip: one sample addition line (3+) containing anti-human immunoglobulin (Ig) and two test performance lines (1+ and +/−) containing human IgG. Values represent reaction intensity. All assays were performed and interpreted according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR.

DNA was isolated from whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells using Qiagen DNA extraction kits (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). To confirm the presence of PTLVs in samples with HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies, a previously described diagnostic tax-rex PCR allowing generic as well as type-specific detection of PTLVs was done (38). The generic PCR proved to be highly sensitive in detecting PTLV strains, and the discriminatory PCRs had high sensitivities and specificities.

For a subset of STLV-1- and STLV-3-positive samples, we also sequenced part of env and/or the long terminal repeat (LTR). For STLV-1, the complete LTR (755 bp) was amplified with a combination of previously described primers (20). A 522-bp region of the env gene, coding for most of gp21 and part of the carboxyl-terminal region of gp46, was amplified and sequenced with previously described primers (20). For STLV-3, a 540-bp fragment in the LTR region was amplified with a combination of previously described and newly designed primers: AV51 (38) and pX-LTRAS (5′-TTTATAGGACCCAGGGTTCTT-3′ [positions 8450 to 8470 in PH969]) for the first round and pX-LTRS (5′-CRGGCACACRGGYCTACTCCC-3′ [positions 7932 to 7952 in PH969]) and pX-LTRAS for the second round. R represents A or G; Y represents C or T. PCRs for both rounds were performed using the Expand High Fidelity PCR kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) and included a hot start (94°C for 2 min) with the following cycle conditions: 10 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min followed by 25 cycles with extension at 72°C for 1 min in the first cycle and for times increasing by an increment of 5 s per cycle thereafter. Amplification was completed by a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. PCR products were sequenced using cycle sequencing and dye terminator methodologies (ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq FS DNA polymerase [PE Biosystems, Warrington, England]) on an automated sequencer (ABI 373, stretch model; Applied Biosystems) either directly or following cloning into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Lyon, France).

To test for DNA degradation, a 1,151-bp region of the glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase gene was amplified using the primers GPD-F1 (5′-CATTACCAGCTCCATGACCAGGAC-3′) and GPD-R1 (5′-GTGTTCCCAGGTGACCCTCTGGC-3′) in a single-round PCR with the following conditions: 94°C for 2 min and then 35 cycles at 94°C for 20 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (26).

Phylogenetic analyses.

Newly derived STLV nucleotide sequences were aligned with reference sequences from GenBank using CLUSTAL W (32) with minor manual adjustments. Gaps in the alignment were omitted from further analyses. The STLV-1 LTR and env phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method and/or the maximum likelihood (ML) method with the Tamura Nei substitution model using PAUP*4.0b10 software (30). The reliability of branching orders was tested using the bootstrap approach (1,000 replicates) for the NJ tree, whereas P values were obtained for the ML tree with the zero branch length test. The STLV-3 LTR (463 nucleotides) and PTLV tax (180 nucleotides) phylogenies were investigated with the software package PAUP* version 4.0b10 (30). NJ and ML trees were constructed under the most appropriate evolutionary model tested with MODELTEST 3-06 (27). For the LTR and tax sequences, the transitional model and transversional model, respectively, each allowing five different substitution rate categories including gamma distribution rate heterogeneity, provided the best fit to the data. The NJ trees were constructed by iterative optimization of the model parameters, followed by a bootstrap analysis of 1,000 replicates. The ML trees were constructed by starting from the NJ tree with optimized parameters by using a heuristic search with the nearest-neighbor interchange and the subtree-pruning-regrafting branch-swapping algorithm (28). Additionally, the P values were estimated for the branches of the ML trees with the branch length confidence test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The new sequences have been deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: AY496626 to AY496638 (LTR from STLV-1), AY496596 to AY496606 (env from STLV-1), AY496607 to AY496618 (tax from STLV-1), AY496588 to AY496595 (tax from STLV-3), and AY496619 to AY496625(LTR from STLV-3).

RESULTS

Estimates of prevalence of STLV infection in bush meat and pet monkey samples.

Blood specimens were obtained from a total of 524 nonhuman primates representing 18 different species. All the animals were wild caught in Cameroon. Whole blood was collected from 328 animals that were sold as bush meat at markets in the capital city of Yaounde, in nearby villages, and at logging concessions in southeastern Cameroon. The great majority (86.4%) of these animals were adults. We also collected blood from 196 pet primates, most of which (74.4%) were still infants or juveniles at the time of sampling. Most primates originated from the southern part of the country.

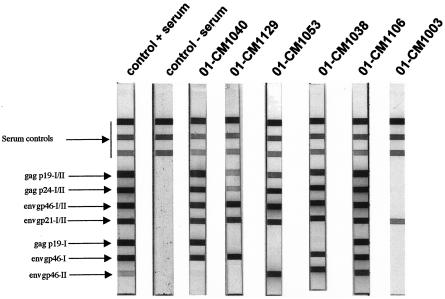

In order to detect PTLV infection in nonhuman primates, we used commercially available HTLV-1-HTLV-2 assays since all previously reported STLV infections were also identified through cross-reactivity with HTLV antigens. A total of 59 (11.2%) of 524 samples tested reacted strongly in the HTLV-1-HTLV-2 ELISA (Table 1). All ELISA reactive samples were retested with the INNO-LIA HTLV I/II confirmatory assay, and the results are summarized in Table 1. Among the 59 samples, 37 were confirmed as HTLV-1 positive, 9 were confirmed as HTLV-2 positive, 10 were confirmed as HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 positive, and results for 3 were indeterminate. Figure 1 illustrates the kind of INNO-LIA reactivities that were typically observed. Overall, HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies were detected in 9 of the 18 primate species tested, and the prevalences of seroreactivity (positive or indeterminate results) in the different species ranged from 0.8 to 66%. Moreover, we identified for the first time STLV sequences in talapoins, mustached monkeys, and gorillas. As expected, prevalences were significantly lower in pet animals, which were mainly infants or juveniles, than in bush meat primates, which were predominantly adult animals (1.5 versus 16.9%, respectively; data not shown). Surprisingly, corresponding to differences in species, extreme differences in prevalences of HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies were observed: up to 89% of agile mangabey bush meat was infected with STLV, whereas only 0.96% of mustached monkeys were infected. For the majority of the 9 out of 18 primate species without HTLV antibodies, the numbers of adult animals tested were low, which may explain the lack of reactivity. For example, we did not observe a positive reaction in samples from red-capped mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus) and mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona), although STLV-3 and STLV-1 infections, respectively, were previously documented in these species (23, 24). Interestingly, we observed 10 agile mangabeys with antibodies that cross-reacted with HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-specific antigens.

FIG. 1.

Detection of HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-cross-reactive antibodies in sera from agile mangabeys (Cercocebus agilis) by using a line immunoassay (INNO-LIA HTLV confirmation; Innogenetics). The HTLV antigens include recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides which are either common to HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 or specific to one of the two viruses. The first three control lines contain human IgG in different concentrations and are followed by four confirmation lines (two gag and two env HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 antigen lines) and three discriminatory lines (two gag HTLV-1 peptides and one env HTLV-2 peptide) at the bottom of the strip. Plasma samples from HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-negative and -positive individuals are shown as controls on the left. Lanes labeled 01-CM1040 and 01-CM1129 represent STLV-1-seropostive Cercocebus agilis; lane 01-CM1053 represents STLV-3-seropositive Cercocebus agilis, and lanes 01-CM1038 and 01-CM1106 represent STLV-1- and STLV-3-seropositive Cercocebus agilis. Lane 01-CM1003 represents an example of plasma with indeterminate serology.

Confirmation of STLV infection by confirmatory and discriminatory PCR analysis of the tax gene.

In order to confirm whether animals with HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies were infected with a PTLV and to determine with which type of PTLV, we performed PCR using highly cross-reactive tax primer pairs previously shown to amplify sequences from a variety of divergent HTLV and STLV strains and known to have a high specificity in characterizing the PTLV type. Among the 59 samples with a positive or indeterminate serology, 41 samples for which sufficient additional material was available were tested by generic PCR followed by type-specific PCR to discriminate between STLV-1, STLV-2, and STLV-3. Among the 41 samples, 24 were positive for HTLV-1, 9 were positive for HTLV-2, 5 were positive for HTLV-1 and HTLV-2, and 3 had an indeterminate serology in the INNO-LIA HTLV I/II assay. The two HTLV-2-positive samples from greater spot-nosed monkeys have been previously described and were identified as being infected with a new SLTV-3 variant (39). The tax PCR results are summarized in Table 2. Among the 24 HTLV-1-positive samples, 5 were negative by PCR, 18 were positive for STLV-1, and in 1 sample (from animal 01CM-1135) STLV-1 and STLV-3 were detected. This dual infection was confirmed by sequence analysis of the tax fragments. All seven HTLV-2-seropositive samples were reactive with the STLV-3-specific tax primers only, which was confirmed by sequence analysis of four samples (Fig. 2). Among the five samples reactive with HTLV-1- and HTLV-2-specific antigens in the line immunoassay, three were determined to carry both STLV-1 and STLV-3, and the remaining two were found to carry only HTLV-1. In two of the three samples with indeterminate HTLV serology, no viruses could be amplified with the generic primers, and in the remaining sample, STLV-3 was present and confirmed by sequence analysis of the tax fragment.

TABLE 2.

PTLV confirmation and discrimination by generic and type-specific tax PCR for HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 antibody cross-reactive samples

| Species | Virus identification by INNO-LIA HTLVI/II | No. of samples tested | No. of samples positive by tax PCR for:

|

No. of samples negative by tax PCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STLV-1 | STLV-3 | STLV-1 and STLV-3 | ||||

| Cercocebus agilis | HTLV-1 | 14 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| HTLV-2 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Indeterminate HTLV | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cercopithecus nictitans | HTLV-1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HTLV-2 | 2 | 0 | 2a | 0 | 0 | |

| Cercopithecus pogonias | HTLV-1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chlorocebus tantalus | HTLV-1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miopithecus ogouensis | HTLV-1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mandrillus sphinx | HTLV-1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cercopithecus cephus | HTLV-1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pan troglodytes | Indeterminate HTLV | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Gorilla gorilla | HTLV-1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | HTLV-1 | 24 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| HTLV-2 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Indeterminate HTLV | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 41 | 20 | 10 | 4 | 7 | |

Previously reported to be infected with STLV-3.

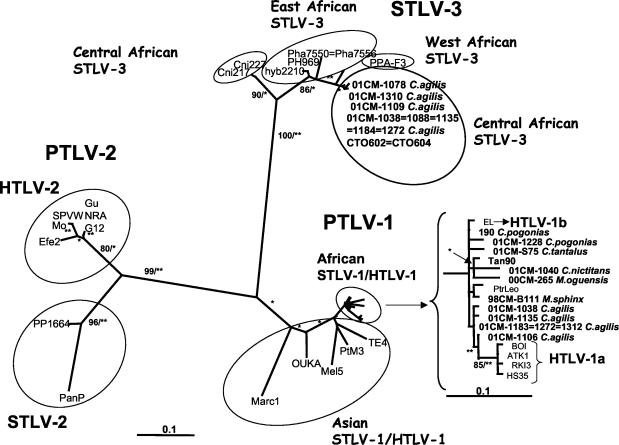

FIG. 2.

PAUP* NJ tree of a 219-bp tax-rex fragment including sequences from reference strains of each PTLV type and subtype with the bootstrap values (in percentages) and P values (**, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05) noted on the branches.

Overall, we confirmed the presence of STLVs in eight of the nine primate species in which we observed HTLV-cross-reactive antibodies. Only among chimpanzees, where we observed one animal with indeterminate HTLV serology, could no STLV infection be demonstrated by PCR. All samples which were identified as HTLV-2 positive by serology were in fact infected with an STLV-3 strain. More interestingly, we observed that one primate species can be infected with two different STLV types; more precisely, STLV-1 and STLV-3 infections were observed in agile mangabeys and in greater spot-nosed monkeys. In addition, we showed that the same animal can be infected with both viruses at the same time. We identified four agile mangabeys (animals 01CM-1038, 01CM-1122, 01CM-1135, and 01CM-1272) that were coinfected with STLV-1 and STLV-3. Figure 2 shows the phylogenetic tree analysis of the tax sequences and encompasses results of the diagnostic and discriminatory tax PCRs for a subset of samples. It is clear from this figure that the previously reported tax STLV-3 sequences from greater spot-nosed monkeys formed a distinct, well-supported (90% bootstrap support for NJ; P of <0.05 for ML) cluster within the STLV-3 group. All other STLV-3 strains clustered together but separately from the greater spot-nosed monkey STLV-3 strains, with a reasonable bootstrap support for NJ (86%) and statistical support for ML (P < 0.05). The further clustering pattern among these eastern, western, and central African STLV-3 strains was more or less according to geographic origins of the STLV host species. Due to the low genetic diversity in tax and the shortness of the fragment, however, the topology among these STLV-3 strains was not well supported. Based on this 180-bp fragment, five sequences from agile mangabey virus strains were even identical to sequences from the previously described strains from red-capped mangabeys (CTO602 and CTO604) (23). The STLV-1 strains clustered with other African HTLV-1 and STLV-1 strains, but the support here was also rather low. Moreover, we identified for the first time STLV sequences in talapoins, mustached monkeys, and gorillas. Therefore, we further investigated longer fragments from these STLV-1 and STLV-3 strains in more divergent gene regions such as the LTR and/or env.

env and LTR sequence analysis of STLV-1 strains obtained from different primate species.

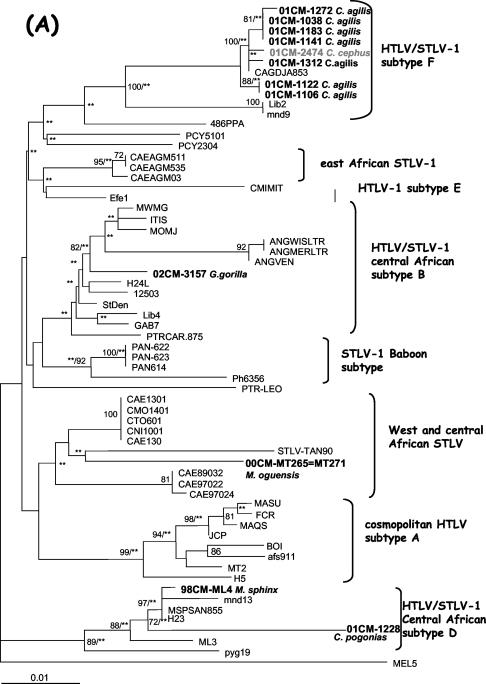

The complete STLV-1 LTR was sequenced for 10 STLV-1-infected and 3 STLV-1- and STLV-3-coinfected animals. The 10 STLV-1-infected animals were representatives of the following primate species: agile mangabeys (four), mustached monkeys (one), crested monas (one), mandrills (two), and talapoins (two). The three coinfected animals (01CM-1038, 01CM-1122, and 01CM-1272) were all agile mangabeys. Figure 3 shows the phylogenetic tree analyses of the LTRs and env. Phylogenetic tree analyses of the new sequences together with previously published STLV and HTLV sequences representing the different HTLV-1-STLV-1 subtypes using both NJ and ML revealed that all sequences from agile mangabeys were closely related to one another (98.9 to 100% identity) and to a previously published STLV-1 sequence obtained from an agile mangabey (25) (99.3 to 99.7% identity) captured in southeast Cameroon (NJ, bootstrap values of 54 and 100%; ML, P of <0.001 and 0.008). The STLV-1 LTR sequence from the only mustached monkey also clustered with the STLV-1 sequences from agile mangabeys (99.1 to 99.3% identity) from the same area in Cameroon (25) (NJ, bootstrap value of 61%; ML, P of <0.001). The LTR sequences from STLVs obtained from agile mangabeys and mustached monkeys clustered with the sequence from subtype F identified in an individual from Gabon (96 to 96.6% identity with the Lib2 sequence) with 86% bootstrap support for NJ and a P value of <0.001 for ML. The STLV-1 sequences from the mandrills from our study and from the crested mona clustered with high support values with sequences from the central African subtype D in both trees (96% identity between sequences from strains 1228 and H23 and 99.5% identity between sequences from strains ML4 and H23). The sequences obtained from talapoins clustered with those of STLVs from western Africa and western central Africa (NJ, bootstrap value of 60%; ML, P of <0.001). The STLV-1 strain obtained from a gorilla clustered with HTLV-1 subtype B (98.2% identity with H24; NJ, bootstrap value of 82%; ML, P of <0.001).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among new STLV-1 strains from Cercocebus agilis, Cercopithecus cephus, Gorilla gorilla, Mandrillus sphinx, Miopithecus ogouensis, and Cercopithecus pogonias and known STLV-1 and HTLV-1 strains from the different subtypes. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using LTR (A) and env (B) sequences as described in Materials and Methods. The numbers along the branches are the bootstrap values (in percentages), and two asterisks indicate that the branch has a P value of <0.001 in the ML analysis. Horizontal branch lengths are drawn to scale.

Partial env sequences were also obtained from the above-described samples except from that from the mustached monkey. Phylogenetic tree analysis of the env sequences showed clustering patterns similar to those determined by analysis of the LTR region.

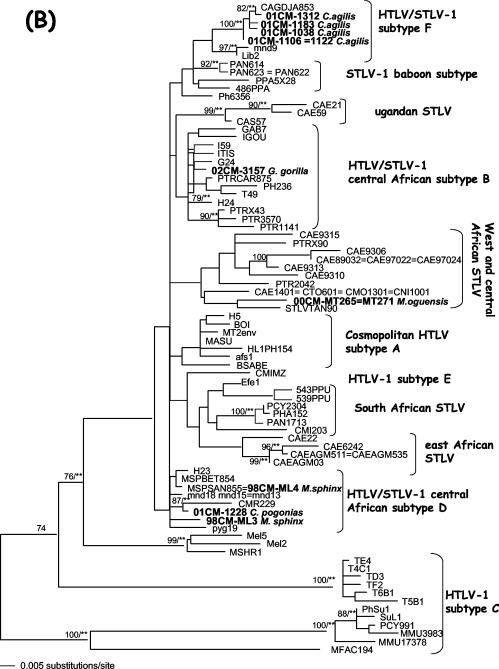

LTR sequence analysis of STLV-3 strains obtained from STLV-3-infected and STLV-1- and STLV-3-coinfected agile mangabeys.

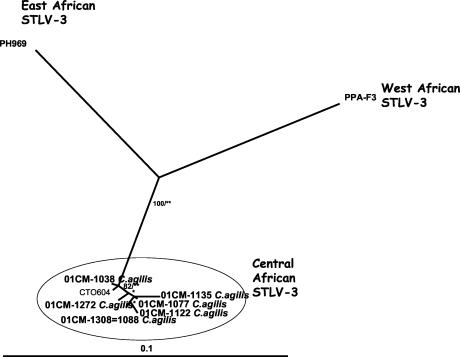

Fragments of 540 bp comprising the LTR regions of STLV-3 strains were obtained from four STLV-3-infected and three STLV-1- and STLV-3-coinfected animals. All the new STLV-3 sequences were closely related to one another (97.8 to 100% identity) and were also most closely related to an STLV-3 sequence (97.8 to 99.6% identity) obtained from a recently described red-capped mangabey from Cameroon (23). Even with this limited number of STLV-3 LTR sequences available in the GenBank database, we observed a tendency toward STLV-3 clustering according to the geographic origins of the viral host species. Similar to those of STLV-1, STLV-3 sequences from coinfected animals did not form a separate subcluster. For the STLV-3-infected greater spot-nosed monkeys, for which the tax sequences were previously reported, we were not able to amplify the LTR fragment due to the degraded nature of the DNA (39). Figure 4 shows the phylogenetic tree analysis of the STLV-3 LTR sequences.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships among new STLV-3 strains from Cercocebus agilis and known STLV-3 strains from different primate species. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using LTR sequences as described in Materials and Methods. The bootstrap values (in percentages) and P values (**, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05) are indicated on the branches.

DISCUSSION

The majority of previous studies of STLV infection have relied almost exclusively on surveys of captive monkeys or apes that were either kept as pets or housed at zoos or primate centers. The great majority of pet monkeys are acquired at a very young age, often when their parents are killed by hunters. STLV infection rates of captive monkeys may thus not accurately reflect STLV infection prevalence rates in the wild.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of HTLV and STLV strains showed that zoonotic transfers of STLV to humans have occurred on several occasions (37), but no study has examined the prevalences of STLV infection among African primates that are frequently hunted or kept as pets. In this paper, we collected blood from 524 monkeys representing 18 different species. All of the animals were wild caught in the rain forests of Cameroon and sampled as either bush meat or pet animals. This approach allowed us simultaneously to identify STLV infection prevalence rates in wild primate populations and to determine to what extent humans are exposed to STLVs. We detected cross-reactive antibodies suggesting PTLV infection in 11% of all tested animals. STLV infection was confirmed by PCR in 8 of the 18 species tested, and phylogenetic analyses revealed the presence of STLVs clustering in different PTLV types. We confirmed STLV-1 infection in three species previously identified as STLV carriers by serology only, namely, mustached monkeys (Cercopithecus cephus), talapoins (Miopithecus ogouensis), and gorillas (Gorilla gorilla). We showed also for the first time the presence of STLV-3 infection in agile mangabeys (Cercocebus agilis), and even coinfection with STLV-1 and STLV-3 was observed in this primate species.

Our data reveal for the first time that a considerable proportion of wild-living primates in Cameroon are infected with STLV and that these primates may be a source of infection to those who come in contact with them. Although new STLV-infected host species were identified and new STLV variants were characterized, it is likely that our data represent only minimal estimates concerning STLV prevalences and STLV diversity in Cameroon because not all native primate species were tested and many were undersampled because they were either rare or absent in the regions of Cameroon where we sampled for this study. For example, the absence of reactive sera from mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona) and red-capped mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus), two species known to harbor STLV, must be due to the low numbers of blood samples analyzed (23, 24).

Similar to that with HIV, human infection with HTLV-1 and HTLV-2 most likely resulted from cutaneous or mucous membrane exposure to infected blood during the hunting and butchering of STLV-infected primates for food or from bites from STLV-infected pet animals. Although no HTLV-3 infection is yet described in humans, our study shows that humans are exposed to STLV-3-infected primate bush meat from greater spot-nosed monkeys and agile mangabeys and possibly other, not-yet-identified STLV-3-harboring primate species. Samples from STLV-3-infected animals either reacted with HTLV-2 antigens in the INNO-LIA assay or had an indeterminate HTLV serology. It will thus be important to genetically characterize human samples with HTLV-2 or indeterminate HTLV serology to study whether STLV-3 cross-species transmission between primates and humans has already occurred and, if so, whether this infection is associated with any disease in humans. Indeterminate HTLV Western blot patterns are frequently observed in central Africa, and although a majority of such patterns may be due to other environmental (viral or paretic) factors, the possibility for HTLV-3 infection has to be further explored (19). Bush meat hunting, to provide animal proteins for the family and a source of income, has a long-standing tradition throughout sub-Saharan Africa (1, 7). However, the bush meat trade has increased in the last decades. Commercial logging, together with road construction into remote forest areas, led to human migration and the development of social and economic networks in previously inaccessible forest areas. Villages around logging concessions have grown from a few hundred to several thousand inhabitants in just a few years (2, 41). These socioeconomic changes suggest that the magnitude of human exposure to primates infected with STLV has increased, as have the social and environmental conditions that would be expected to support the emergence of new zoonotic infections with STLVs.

Our study shows clearly that significantly more adult monkeys than juveniles are infected (1.5% prevalence in pets versus 16.9% in bush meat samples), thus suggesting a low vertical transmission rate and confirming that estimates of the prevalence of STLV infection have to be made using adult animals. We also observed extreme differences in prevalence rates among different primate species. We tested large numbers of greater spot-nosed and mustached monkeys, but only a few animals were determined to be positive. In contrast, more than 80% of adult agile mangabeys were infected with a PTLV, and even STLV-1 and STLV-3 infections and STLV-1-STLV-3 coinfections were observed among these animals in the wild. Another study among wild primate populations in Ethiopia also revealed discrepancies among STLV infection prevalences among different baboon species (31). STLV-3 and STLV-1 infections were observed, and one hybrid baboon was positive by STLV-1- and STLV-L-specific PCR, suggesting a dual infection (31). It is known for HTLV infection in humans that geographic and/or intrafamilial clusters with high prevalences of infection exist (16). It has to be further investigated whether the high prevalences observed in certain monkeys are specific for the species or whether, similar to those among humans, geographic clusters also exist among nonhuman primates. Therefore, additional prevalence studies of STLV infections among wild primate populations have to be done in other regions of Cameroon and Africa.

In conclusion, our study shows that humans are exposed to a large variety of STLV-1 and STLV-3 strains. Further studies are needed to determine whether zoonotic transmissions of STLVs, especially STLV-3, from primates has occurred. In order to understand the evolution of PTLVs, it will be important to identify and compare STLVs from primate species from western, central, and eastern Africa, as well as to determine STLV infection prevalences among wild primate populations. These studies will allow us to understand the origin, evolution, and spread of these viruses into different primate and human populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cameroonian Ministries of Health and of Environment and Forestry for permission to perform this study and the staff from project PRESICA for logistical support and assistance in the field.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI 50529), the Agence National de Recherche sur le SIDA (ANRS), and the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (grant 0288.01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Asibey, E. O. 1974. Wildlife as a source of protein in Africa south of the Sahara. Biol. Conserv. 6:32-39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auzel, P., and R. Hardin. 2000. Colonial history, concessionary politics, and collaborative management of Equatorial African rain forests, p. 21-38. In M. Bakarr, G. Da Fonseca, W. Konstant, R. Mittermeier, and K. Painemilla (ed.), Hunting and bushmeat utilization in the African rain forest. Conservation International, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Bennett, E. L., and J. G. Robinson. 2000. Hunting for the snark, p. 1-9. In J. G. Robinson, and E. L. Bennett (ed.), Hunting for sustainability in tropical forests. Columbia University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Delaporte, E., A. Dupont, M. Peeters, R. Josse, M. Merlin, D. Schrijvers, B. Hamono, L. Bedjabaga, H. Cheringou, F. Boyer, et al. 1988. Epidemiology of HTLV-I in Gabon (Western Equatorial Africa). Int. J. Cancer 42:687-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delaporte, E., M. Peeters, J. P. Durand, A. Dupont, D. Schrijvers, L. Bedjabaga, C. Honore, S. Ossari, A. Trebucq, R. Josse, et al. 1989. Seroepidemiological survey of HTLV-I infection among randomized populations of western central African countries. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2:410-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao, F., E. Bailes, D. L. Robertson, Y. Chen, C. M. Rodenburg, S. F. Michael, L. B. Cummins, L. O. Arthur, M. Peeters, G. M. Shaw, P. M. Sharp, and B. H. Hahn. 1999. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397:436-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geist, V. 1988. How markets for wildlife meat and parts, and the sale of hunting privileges, jeopardize wildlife conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2:15-26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gessain, A., and R. Mahieux. 2000. Epidemiology, origin and genetic diversity of HTLV-1 retrovirus and STLV-1 simian affiliated retrovirus. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 93:163-171. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gessain, A., Y. Plumelle, K. Sanhadji, F. Barin, L. Gazzolo, M. Constant-Desportes, N. Pascaline, J. Diebold, and G. De-The. 1986. Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia associated with HTLV-I virus in Martinique: apropos of 2 cases. Nouv. Rev. Fr. Hematol. 28:107-113. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groves, C. 2001. Primate taxonomy. Smithsonian series in comparative evolutionary biology. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Hirsch, V. M., R. A. Olmsted, M. Murphey-Corb, R. H. Purcell, and P. R. Johnson. 1989. An African primate lentivirus (SIVsm) closely related to HIV-2. Nature 339:389-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibuki, K., E. Ido, S. Setiyaningsih, M. Yamashita, L. R. Agus, J. Takehisa, T. Miura, S. Dondin, and M. Hayami. 1997. Isolation of STLV-I from orangutan, a great ape species in Southeast Asia, and its relation to other HTLV-Is/STLV-Is. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 88:1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa, K., M. Fukasawa, H. Tsujimoto, J. G. Else, M. Isahakia, N. K. Ubhi, T. Ishida, O. Takenaka, Y. Kawamoto, T. Shotake, et al. 1987. Serological survey and virus isolation of simian T-cell leukemia/T-lymphotropic virus type I (STLV-I) in non-human primates in their native countries. Int. J. Cancer 40:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingdon, J. 1997. The Kingdon field guide to African mammals. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 15.Koralnik, I. J., E. Boeri, W. C. Saxinger, A. L. Monico, J. Fullen, A. Gessain, H. G. Guo, R. C. Gallo, P. Markham, and V. Kalyanaraman. 1994. Phylogenetic associations of human and simian T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I strains: evidence for interspecies transmission. J. Virol. 68:2693-2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larouze, B., M. Peeters, N. Monplaisir, A. Trebucq, R. Josse, J. Y. Le Hesran, M. C. Dazza, C. Gaudebout, and E. Delaporte. 1990. Epidemiology of HTLV-I infection in its hyperendemic foci (Japan, tropical Africa, Caribbean). Rev. Prat. 40:2120-2123. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine, P. H., E. S. Jaffe, A. Manns, E. L. Murphy, J. Clark, and W. A. Blattner. 1988. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma outside Japan and the Caribbean Basin. Yale J. Biol. Med. 61:215-222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahieux, R., C. Chappey, M. C. Georges-Courbot, G. Dubreuil, P. Mauclere, A. Georges, and A. Gessain. 1998. Simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 from Mandrillus sphinx as a simian counterpart of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 subtype D. J. Virol. 72:10316-10322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahieux, R., P. Horal, P. Mauclere, O. Mercereau-Puijalon, M. Guillotte, L. Meertens, E. Murphy, and A. Gessain. 2000. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Gag indeterminate Western blot patterns in Central Africa: relationship to Plasmodium falciparum infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:4049-4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahieux, R., F. Ibrahim, P. Mauclere, V. Herve, P. Michel, F. Tekaia, C. Chappey, B. Garin, E. Van Der Ryst, B. Guillemain, E. Ledru, E. Delaporte, G. de The, and A. Gessain. 1997. Molecular epidemiology of 58 new African human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) strains: identification of a new and distinct HTLV-1 molecular subtype in Central Africa and in Pygmies. J. Virol. 71:1317-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauclere, P., J. Y. Le Hesran, R. Mahieux, R. Salla, J. Mfoupouendoun, E. T. Abada, J. Millan, G. de The, and A. Gessain. 1997. Demographic, ethnic, and geographic differences between human T cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) type I-seropositive carriers and persons with HTLV-I Gag-indeterminate Western blots in Central Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 176:505-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meertens, L., and A. Gessain. 2003. Divergent simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 3 (STLV-3) in wild-caught Papio hamadryas papio from Senegal: widespread distribution of STLV-3 in Africa. J. Virol. 77:782-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meertens, L., R. Mahieux, P. Mauclere, J. Lewis, and A. Gessain. 2002. Complete sequence of a novel highly divergent simian T-cell lymphotropic virus from wild-caught red-capped mangabeys (Cercocebus torquatus) from Cameroon: a new primate T-lymphotropic virus type 3 subtype. J. Virol. 76:259-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meertens, L., J. Rigoulet, P. Mauclere, M. Van Beveren, G. M. Chen, O. Diop, G. Dubreuil, M. C. Georges-Goubot, J. L. Berthier, J. Lewis, and A. Gessain. 2001. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of 16 novel simian T cell leukemia virus type 1 from Africa: close relationship of STLV-1 from Allenopithecus nigroviridis to HTLV-1 subtype B strains. Virology 287:275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nerrienet, E., L. Meertens, A. Kfutwah, Y. Foupouapouognigni, and A. Gessain. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of simian T-lymphotropic virus (STLV) in wild-caught monkeys and apes from Cameroon: a new STLV-1, related to human T-lymphotropic virus subtype F, in a Cercocebus agilis. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2973-2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peeters, M., V. Courgnaud, B. Abela, P. Auzel, X. Pourrut, F. Bibollet-Ruche, S. Loul, F. Liegeois, C. Butel, D. Koulagna, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, G. M. Shaw, B. H. Hahn, and E. Delaporte. 2002. Risk to human health from a plethora of simian immunodeficiency viruses in primate bushmeat. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:451-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Posada, D., and K. A. Crandall. 1998. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14:817-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers, J. S., and D. L. Swofford. 1999. Multiple local maxima for likelihoods of phylogenetic trees: a simulation study. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16:1079-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saksena, N. K., V. Herve, J. P. Durand, B. Leguenno, O. M. Diop, J. P. Digouette, C. Mathiot, M. C. Muller, J. L. Love, S. Dube, M. P. Sherman, P. M. Benz, S. Erensoy, A. Galat-Luong, G. Galat, B. Paul, D. K. Dube, F. Barre Sinoussi, and B. J. Poiesz. 1994. Seroepidemiologic, molecular, and phylogenetic analyses of simian T-cell leukemia viruses (STLV-I) from various naturally infected monkey species from central and western Africa. Virology 198:297-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swofford, D. L. 1998. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods), version 4.0b10. Sinauer Association, Sunderland, Mass.

- 31.Takemura, T., M. Yamashita, M. K. Shimada, S. Ohkura, T. Shotake, M. Ikeda, T. Miura, and M. Hayami. 2002. High prevalence of simian T-lymphotropic virus type L in wild Ethiopian baboons. J. Virol. 76:1642-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Touze, E., A. Gessain, O. Lyon-Caen, and O. Gout. 1996. Tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-I-associated myelopathy in Europe and in Africa: clinical and epidemiologic aspects. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13(Suppl. 1):S38-S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNAIDS. 2002, posting date. Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. [Online.] UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.unaids.org/en/Resources/Publications/Corporate+publications/report+on+the+global+hiv_aids+epidemic+2002+.asp.

- 35.Van Brussel, M., P. Goubau, R. Rousseau, J. Desmyter, and A. M. Vandamme. 1997. Complete nucleotide sequence of the new simian T-lymphotropic virus, STLV-PH969 from a Hamadryas baboon, and unusual features of its long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 71:5464-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Brussel, M., M. Salemi, H. F. Liu, J. Gabriels, P. Goubau, J. Desmyter, and A. M. Vandamme. 1998. The simian T-lymphotropic virus STLV-PP1664 from Pan paniscus is distinctly related to HTLV-2 but differs in genomic organization. Virology 243:366-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vandamme, A. M., M. Salemi, and J. Desmyter. 1998. The simian origins of the pathogenic human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I. Trends Microbiol. 6:477-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandamme, A. M., K. Van Laethem, H. F. Liu, M. Van Brussel, E. Delaporte, C. M. de Castro Costa, C. Fleischer, G. Taylor, U. Bertazzoni, J. Desmyter, and P. Goubau. 1997. Use of a generic polymerase chain reaction assay detecting human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV) types I, II and divergent simian strains in the evaluation of individuals with indeterminate HTLV serology. J. Med. Virol. 52:1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Dooren, S., M. Salemi, X. Pourrut, M. Peeters, E. Delaporte, M. Van Ranst, and A. M. Vandamme. 2001. Evidence for a second simian T-cell lymphotropic virus type 3 in Cercopithecus nictitans from Cameroon. J. Virol. 75:11939-11941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschoor, E. J., K. S. Warren, H. Niphuis, Heriyanto, R. A. Swan, and J. L. Heeney. 1998. Characterization of a simian T-lymphotropic virus from a wild-caught orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) from Kalimantan, Indonesia. J. Gen. Virol. 79:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkie, D., E. Shaw, F. Rotberg, G. Morelli, and P. Auzel. 2000. Roads, development, and conservation in the Congo Basin. Conserv. Biol. 14:1614-1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]