Abstract

The 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic (MCPA) acid-degrader Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 has recently been isolated from MCPA-degrading bacterial communities. Using Illumina-sequencing, the 5.7 Mb genome of this isolate was sequenced in this study, revealing the 138 kbp plasmid pCADAB1 harboring the 32.5 kbp composite transposon Tn6228 which contains genes encoding proteins for the removal of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and MCPA, as well as the regulation of this pathway. Transposon Tn6228 was confirmed by PCR to be situated on the plasmid and also exist in a circular intermediate state - typical of IS3 elements. The canonical tfdAα-gene of group III 2,4-D degraders, encoding the first step in degradation of 2,4-D and related compounds, was not present in the chromosomal contigs. However, the alternative cadAB genes, also providing the initial degradation step, were found in Tn6228, along with the 2,4-D-degradation-associated genes tfdBCDEFKR and cadR. Putative reductase and ferredoxin genes cadCD of Rieske non-heme iron oxygenases were also present in close proximity to cadAB, suggesting that these might have an unknown role in the initial degradation reaction. Parts of the composite transposon contain sequence displaying high similarity to previously analyzed 2,4-D degradation genes, suggesting rapid dissemination and high conservation of the chlorinated-phenoxyacetic acid (PAA)-degradation genotype among the sphingomonads.

Introduction

2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic (MCPA) and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) are widely used phenoxyacetic acid herbicides that are occasionally found in the Danish groundwater aquifers [1]. The complete degradation of 2,4-D and MCPA have been described with the first step being performed by the products of the genes tfdA, tfdAα or cadAB [2]–[5]. The product of the first catabolic step is then further degraded by the products of genes tfdBCDEF to finally yield β-ketoadipate, which is degraded in the central metabolism [6]. Most attention has been paid to tfdA and tfdAα [3]–[5], [7], while cadAB has been less described [2], [8], [9]. A recent study on MCPA degradation in soil microcosms showed that both the cadA and tfdA genes are simultaneously expressed during MCPA degradation in soil [10], indicating that additional knowledge should be gathered on the cadAB genes if they are to be compared with the well-studied tfdA gene.

Phenoxyacetic acid (PAA) herbicide degraders are generally divided into three categories [5], [9], [11]. The first group consists of β- and γ-proteobacteria, which are characterized by the involvement of the tfdA gene as the first step in the degradation of phenoxyacetic acid herbicides. Within group I degraders, three further subclasses have been described, based on the similarities of the tfdA sequences (class I–III) [12]. Group II consists of α-proteobacteria that are phylogenetically closely related to Bradyrhizobium sp. Remarkably, representatives of this group were initially isolated from pristine environments in Canada, Chile and Hawaii [11]. This group was shown to possess a tfdA-like gene, termed tfdAα, which is 56–60% similar to the representative tfdA gene of the canonical group I degrader Cupriavidus pinatubonensis JMP134 [5]. Group III degraders are α-proteobacteria closely related to the Sphingomonas genus, also harboring the tfdAα gene [9].

The CadAB catabolic proteins have been shown to perform the same initial step in 2,4-D degradation as TfdA. However, CadAB are subunits of a Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase, making its mode of action quite different from the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase action of TfdA [2], [3]. CadAB of Bradyrhizobium sp. HW13 shows homology to the benzoate dioxygenase BenAB and the 2,4,5-T catabolic protein TftAB [2]. The cadA gene has been found in members of both group II and III PAA-herbicide degraders [2], [8], [9], [13]. Some of these bacteria also have the tfdAα gene, displaying a dual-system of degradative genes [9].

Previously, a gene cluster from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 containing the genes cadAB, was cloned into an E. coli, resulting in 2,4-D degradation in this host. Mutational analysis showed that both cadA and cadB were essential for 2,4-D degradation [8]. In this study, the MCPA- and 2,4-D-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas sp. ERG5, recently isolated from the MCPA-degrading bacterial communities described in [14], had its genomic content shotgun sequenced using Illumina-sequencing. This bacterium was shown to have a transposon, harboring cadAB as well as other PAA-herbicide catabolic and regulatory genes, situated on a plasmid containing genes for conjugative transfer.

Methods

DNA extraction and Illumina sequencing

DNA was extracted from strain ERG5 grown on R2A (Difco™) plates at 20°C supplemented with 100 mg/l of MCPA (Fluka Chemie AG), using the PowerLyzer™ UltraClean® Microbial DNA Isolation kit (MOBIO). A swab of bacteria from a single colony was picked for DNA extraction. Cell lysis was performed using the FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals) for 3×30 seconds at 4 m/s with samples chilled on ice between runs. The extracted DNA was quantified using a QUBIT® 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and was measured to be 7.82 ng/µl. The low quantity of DNA was presumably due to the low cell density of Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 when grown in the relatively low nutrient medium R2A (compared to e.g. LB). A paired-end sequencing library for the Illumina was built with an average insert-size of 500 bp using a modified protocol for the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England BioLabs Inc). The library was loaded onto approximately 1/15 of an Illumina flow-cell and 2×100 base paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina® HiSeq 2000 machine.

Genetic analysis

The raw reads were preprocessed using AdapterRemoval [15] and then assembled using the Velvet de-novo assembler (version 1.2.08) [16] with scaffolding switched off. An initial automated annotation was performed using the RAST service [17], while the sequences described in detail in this study were manually annotated using BLASTX with standard parameters [18] and Pfam domain search (version 27.0.) [19]. Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using the EasyGene server [20], [21]. A genetic map of plasmid pCADAB1 was generated using DNAplotter [22]. Copy numbers of genetic elements was estimated by comparing sequence coverages, as seen elsewhere [23].

The following programs and scripts were used for identification and analysis of IS-elements: ISfinder [24], einverted from the EMBOSS software package [25] and COILS [26]. A genetic map of transposon Tn6228 showing nucleotide similarities to gene clusters from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 (accession no. AB353895.1), Sphingomonas sp. tfd44 (accession no. AY598949.1) and Sphingobium herbicidovorans MH (accession no. AJ628861.1) was constructed using Easyfig [27] with BLASTN implemented. The figure was edited for visual improvement in Inkscape [28].

Phylogenetic analysis of CadA

The derived amino acid sequence of the cadA ORF from Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 was used as query for a BLASTX [18] search with standard parameters. Homologous sequences were chosen for analysis from the BLASTX hits with a cutoff value of 50% amino acid identity. The sequences were aligned using the Phylogeny.fr pipeline [29]: sequences were aligned with T-Coffee (v6.85) [30] using the pair-wise alignment methods Mlalign_id_pair and Mslow_pair. Following alignment, ambiguous regions were removed using Gblocks (v0.91b) [31] with the following parameters: minimum length of a block after gap cleaning: 10, no gap positions allowed in final alignment, all segments with contiguous nonconserved positions bigger than 8 were rejected, minimum number of sequences for a flank position: 85%. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method and the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) amino acid substitution model [32], implemented in the PhyML program (v3.0 aLRT) [33], [34]. The reliability for internal branches was assessed using the bootstrapping method with 100 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized with MEGA4.0.2 [35]. Similar trees were constructed for CadBR and TfdBCDEFKR.

PCR for identification of transposon position

Primers for PCR amplification of DNA for capillary sequencing were designed using primer-BLAST [36] and synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany). All primers were designed to have a melting temperature (Tm) of approximately 63°C and are shown in Table 1. The primers were used in different combinations to test for 1) the presence/lack of transposon Tn6228 on plasmid pCADAB1, 2) circular intermediate state of Tn6228, 3) presence of Tn6228 in the pCADAB1 at 3′ end of transposon, 4) presence of Tn6228 in pCADAB1 at the 5′ end of transposon. The primed positions are shown in Figure 1 and the combinations of primers are shown in Table 2. PCRs were set up in 20 µl reactions containing 200 µM dNTPs, 0.5 µM of both forward and reverse primers, 0.2 µl of Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs), 4 µl of 5× Phusion GC reaction buffer, 3% DMSO, 1 µl template DNA and up to 20 µl of Molecular Biology Grade Water (MOBIO). PCRs were performed on a S1000™ Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD) using a Touch Down (TD) PCR program: an initial denaturation step at 98°C for 40 seconds followed by 15 cycles with denaturation at 98°C for 10 seconds, annealing starting at 72°C for 15 seconds and lowered by 1°C per cycle, elongation at 72°C for 80 seconds. After TD cycling, the protocol continued with 20 cycles of 98°C for 10 seconds, 57°C for 15 seconds, 72°C for 80 seconds and a final elongation step of 72°C for 5 minutes. TD-PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel, which was cast using modified TAE-buffer from the Millipore DNA Gel Extraction Kit and containing 0.5 µg/ml ethidium bromide. The amplification products were excised from the gel using Millipore DNA Gel Extraction Kit and DNA concentrations were measured using the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen). The extracted PCR products were shipped to Macrogen for capillary sequencing.

Table 1. Primers used for TD-PCR.

| Primer | Type | Target region | Sequence (5′-3′) | Anneal temp (°C) |

| 251F | Forward primer | 5′ end of transposon | AACCGGAACCCATCGGCATC | 62.89 |

| 251R | Reverse primer | 3′ end of transposon | CGGAACCGCTGCTCCATACC | 63.25 |

| 74F | Forward primer | Upstream of transposon | CACCTTGACCACGGGTTCGG | 63.33 |

| 74R | Reverse primer | Downstream of transposon | CCAAAGCGGTATCTGCCGTGA | 63.02 |

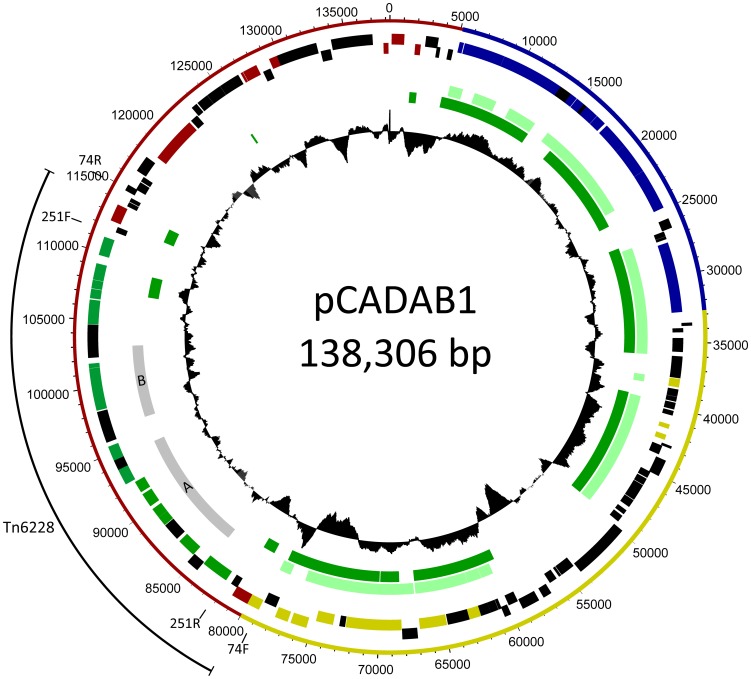

Figure 1. Genetic map of plasmid pCADAB1 and composite transposon Tn6228.

The outer ring shows the functional regions of the plasmid: conjugative transfer (blue), plasmid stability and maintenance (yellow) and region containing multiple IS-elements (red). The composite transposon Tn6228 is displayed on the outside of the plasmid backbone (black line) Primers 74F, 74R, 251F and 251R for PCR have been marked on the outer ring. Inside of the backbone, predicted ORFs on either the positive strand (top blocks) or negative strand (bottom blocks) are displayed. Genes involved in degradation of MCPA are highlighted (green). Also highlighted are IS-elements (red), genes related to the type 4 secretion system (blue) and genes involved in plasmid maintenance and stability (yellow). The middle circle shows similarity to other sequences: Grey bars indicate collinear blocks of similarity to A) Sphingomonas sp. tfd44 (acc. no. AY598949.1) and B) Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 (acc. no. AB353895.1), while bright green bars indicate collinearity with plasmid pNL1 (acc. no. CP000676.1) and dark green with plasmid pCAR3 (acc. no. AB270530.1). The minimum nucleotide similarity in collinear blocks is 72%. The inner circle displays the G+C content (window size = 1000, step size = 10).

Table 2. Combination of primers for TD-PCR and tested hypotheses.

| Primerset (primers used) | Tested hypothesis | Predicted fragment size (bp) |

| P1 (74F+74R) | The plasmid only contains the transposase, not the transposon | 3373 |

| P2 (251F+251R) | The transposon has a circular state | 3174 |

| P3 (251F+74R) | The transposon is located on the plasmid in the predicted position. This primerset primes in the 3′-end of transposon | 3333 |

| P4 (74F+251R) | The transposon is located on the plasmid in the predicted position. This primerset primes in the 5′-end of transposon | 3234 |

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The nucleotide sequence of plasmid pCADAB1 has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession number KF494257.

Results

Shotgun sequencing of Sphingomonas sp. ERG5

The MCPA-degrading Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform. Preprocessing and assembly of 12,540,301 paired reads yielded 69 contigs larger than 500 bp. These contigs have a combined size of 5.7 Mb, a G+C content of 63.7% and an average coverage of approximately 91×. The 16S gene sequence of Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 showed 99% similarity to Sphingomonas alpina strain S8-3 (accession no. GQ161989.1).

A single homolog of the TfdA-related taurine catabolism dioxygenase (TauD) was found in the chromosomal contigs; however, the deduced amino acid sequence of this gene showed little similarity to any verified TfdA proteins. The closest TfdA 2,4-D dioxygenase homolog to this gene is that of Ralstonia solanacearum CMR15 (accession no. YP_008997670.1), which is only 31% identical to the taurine dioxygenase of Sphingomonas sp. ERG5.

However, genes homologous to cadAB were located on a 32.5 kbp contig containing a 1266 bp IS3 element. This contig had a G+C content of 62.4% and a coverage of 106.5×. An identical copy of the IS3 element was present in an approximately 106 kbp circular contig (circularity and size confirmed by PCR - data not shown) with a coverage of 97.5× and a G+C content of 63.4%, which contained genes involved in conjugative plasmid transfer, indicating that this contig represents a conjugative plasmid (pCADAB1). The total coverage of the IS3 elements was 199.8×, indicating that this insertion sequence has a copy number of approximately 2. It was hypothesized that the 32.5 kbp contig actually represents a composite transposon (Tn6228), flanked by identical, directly oriented copies of the IS3 elements, which is situated on the conjugative plasmid contig (review on composite transposons [37]). The length of the IS3 elements is longer than the insert-size of the paired-end Illumina sequencing, which prevents the Velvet program from correctly assembling this repeated structure as summarized by [38].

Genetic organization of transposon Tn6228 and plasmid pCADAB1

To investigate the possible position of Tn6228 in plasmid pCADAB1, PCRs were performed (Table 1+2 and Figure 1), followed by sequencing of the PCR products (results not shown). Primer set 1 was designed so that a 3373 bp product would result from the PCR if only the IS3 element is present and not the entire Tn6228. PCR with primer set 2 will yield a 3174 bp product if Tn6228 has a circular state outside pCADAB1, since primers 251F and 251R target the sequence at either end of Tn6228 and prime outwards. Primer sets 3 and 4 use combinations of primers targeting either Tn6228 or pCADAB1 sequence near the IS3 elements. PCR products from these primer sets with the predicted sizes (Table 2) will indicate that Tn6228 is situated on pCADAB1 in the predicted location. The PCR products had the expected sizes, except from that of primer set 1 which was larger than 3373 bp. The bands were excised from the gel and the PCR products were sequenced. The sequencing revealed that PCR using primer sets 3 and 4 had amplified DNA from the predicted location of Tn6228, confirming the predicted position on pCADAB1. The PCR using primer set 2 yielded a product with the predicted size, and sequencing of the PCR product confirmed that Tn6228 indeed has a circular state, as well as linearly inserted into pCADAB1. The product from the PCR with primer set 1 could not be sequenced properly, yielding only base calls of poor quality.

The organization of pCADAB1 with Tn6228 in the determined position is shown in Figure 1. Here, predicted genes, G+C content and regions of homology are shown. With PCR and PCR product sequencing it was confirmed that the transposon exists in a circular state, as well as in a linear state in the plasmid which is typical for IS3 elements [39] (reviewed by [40]). Identical copies of the IS3 element were determined to be flanking the composite transposon, when inserted into the plasmid. The IS3-like transposase found here contained a leucine-zipper motif, a DDE-motif and imperfect inverted repeats - all of which are expected to be present in a functional IS3-element [41].

Annotation of genes in transposon Tn6228

EasyGene ORF prediction of the transposon contig yielded 27 ORFs, which are numbered relative to plasmid start in the following sections. Manual annotation using BLASTX and Pfam domain search resulted in the predicted genes shown in Table S1 and Figure 2.

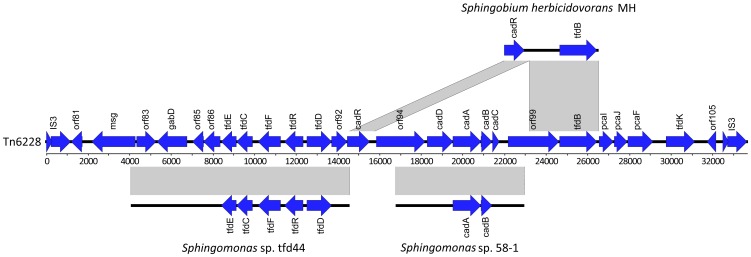

Figure 2. Genetic organization of the composite transposon Tn6228 and comparison to other gene clusters.

Genes are marked with blue arrows. Gene abbreviations are msg: malate synthase G, gabD: putative succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, tfdE: dienelacatone hydrolase, tfdC: chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase, tfdF: maleylacetate reductase, tfdR: LysR family transcriptional regulator, tfdD: chloromuconate cycloisomerase, tauE/safE: sulfite exporter, cadR: AraC family transcriptional regulator, cadD: oxidoreductase component of Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase (RO), cadA: large subunit of 2,4-D oxygenase, cadB: small subunit of 2,4-D oxygenase, cadC: ferredoxin component of RO, tfdB: dichlorophenol hydroxylase, pcaI: 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase A subunit, pcaJ: 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase B subunit, pcaF: beta-ketoadipyl CoA thiolase, tfdK: transport protein. Nucleotide similarity is shown as gray bars linking to the corresponding gene clusters in Sphingomonas sp. tfd44 (acc. no. AY598949.1), Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 (acc. no. AB353895.1) and Sphingobium herbicidovorans MH (acc. no. AJ628861.1). Nucleotide similarities are shown with a cutoff value of 98% and were identified with BLASTN as implemented in Easyfig [27]. The composite figure shown here was compiled in Inkscape [28].

Within the Tn6228 transposon, three different gene clusters showed high similarity to previously identified clusters of 2,4-D catabolic genes (Figure 1 and 2). The first, 10493 bp in length, spans transposon-relative positions 2894–13386, contains 10 predicted ORFs and shares high nucleotide similarity (99% identity) to a chlorocatechol catabolic gene cluster from Sphingomonas sp. tfd44 [42] (accession no. AY598949.1). Due to sequence similarity, as well as BLASTX and Pfam results, ORFs 83–92 in this gene cluster were designated to encode putative LysR-type regulator, putative succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase GabD, hypothetical protein, hypothetical protein with Rieske domain, dienelactone hydrolase TfdE, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase TfdC, maleylacetate reductase TfdF, LysR-type regulator TfdR, muconate lactonizing enzyme TfdD and putative Tau/SafE sulfite exporter, respectively. The second gene cluster is 6182 bp in length and is located 2212 bp downstream of the first cluster in transposon-relative positions 15599–21780. It shows high nucleotide similarity (98% identity) to a clone fragment from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 [8] (accession no. AB353895.1) and contains ORFs 95–98, which are annotated to encode pyridine nucleotide-disulphide oxidoreductase, large subunit of 2,4-D oxygenase CadA, small subunit of 2,4-D oxygenase CadB, and putative 2-hydroxybenzoate 5-hydroxylase ferredoxin CadC, respectively. Between the gene clusters, ORFs 93 and 94 encode transcriptional regulator CadR and a putative TonB-dependent receptor, respectively. Upstream of the first gene cluster, ORFs 81 and 82 encode an unknown hypothetical protein and a malate synthase G, respectively. Downstream of the second gene cluster, ORFs 99–107 were predicted to encode a putative TonB-dependent receptor, dichlorophenol hydroxylase TfdB, A and B subunits of a 3-oxoacid CoA-transferase PcaIJ, a beta-ketoadipyl CoA thiolase PcaF, transport protein TfdK, a putative diguanylate cyclase and two ORFs constituting a transposase of the IS3 family. The genes cadR, orf99 and tfdB showed high nucleotide similarity with a gene cluster from Sphingobium herbicidovorans MH (accession no. AJ628861.1), although orf99 might be truncated in this bacterium (Figure 2).

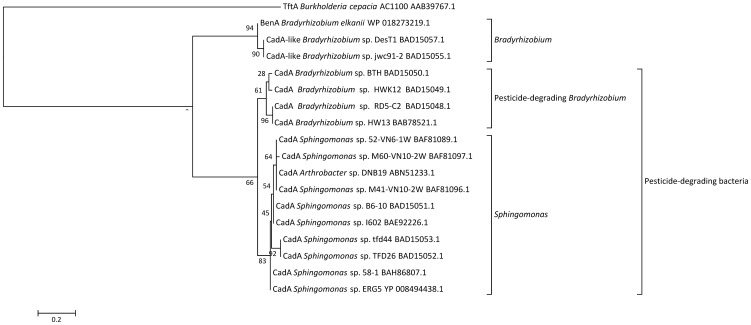

A phylogenetic tree of 18 selected CadA amino acid sequences from the genera Sphingomonas, Bradyrhizobium, Burkholderia and Arthrobacter was constructed (Figure 3). This tree shows a clustering of CadA, similar to a clustering previously described [5], where CadA can be separated into 3 different clades: a Sphingomonas clade, a 2,4-D degrading Bradyrhizobium clade and a clade containing Bradyrhizobium not degrading 2,4-D. The Sphingomonas clade also contains a single member of the Arthrobacter genus, which has possibly acquired the cadA gene through horizontal gene transfer (HGT).

Figure 3. Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationship of representative CadA sequences.

Representative sequences for alignment were identified from a BLASTX search using the derived amino acid sequence of CadA from Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 as query. BLASTX hits were picked for comparison with a cutoff value of 50% for amino acid identities. The support of each branch, as determined from 100 bootstrap samples, is indicated as a percentage at each node. Sequences were aligned with T-Coffee (v6.85) [30] and the alignment was curated with Gblocks (v0.91b) [31]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using a maximum likelihood approach and the JTT substitution model [32] in the PhyML program (v3.0 aLRT) [33], [34]. The resulting unrooted phylogenetic tree was visualized in MEGA4.0.2[35].

Properties of plasmid and transposon

EasyGene predicted 110 ORFs in the plasmid pCADAB1, and an automated annotation by RAST revealed that the predicted genes could be divided into cohesive regions of function: conjugal transfer, plasmid maintenance/stability and a region containing various IS-elements (Figure 1). The regions for conjugal transfer and maintenance/stability showed similarity in their nucleotide sequences to the sphingomonad plasmids pCAR3 (accession no. AB270530.1) and pNL1 (accession no. CP000676.1), which have been shown to harbor the genes involved in degradation of xenobiotics [43], [44]. Within the conjugal transfer region, the genes traALEKBVCFWUNFHGID, trbC and dsbC encode a type 4 secretion system (T4SS) for conjugative transfer. These genes are very similar to those of pNL1 (Figure 1), which has been shown to be capable of conjugative transfer [44], [45]. The maintenance/stability region of pERG5 contains genes encoding plasmid replication and partitioning systems, a toxin-antitoxin system, a multimer resolution system and restriction-modification systems.

The transposon was assembled by Velvet as one contig at a size of approximately 32.5 kbp, a G+C content of 62.4% and a coverage of 106.5×. Based on the average sequence coverages of the transposon, plasmid and chromosome, it was estimated that the transposon copy number is 1.17 relative to the chromosome and 1.09 relative to the plasmid. This approach for estimating copy numbers has been utilized previously [23]. Two ORFs (ORF 106–107) were predicted to constitute an IS-element gene, which was confirmed by ISfinder [24] and showed 84% identity with the IS3 family (group IS407) transposase ISSpma1 from Sphingopyxis macrogoltabida (accession no. AB196775). The IS-element has imperfect inverted repeats of 49 bp (32/49) (IRL: TGATCTGCCCCCTTCTGAGTGGTCCAAAATCTCTGTTATTTTGGATCAT and IRR: ACAATGCACTAACAATCAACACGGACCACTCAGTGGGGGCCGGTCA). Furthermore, a leucine-zipper motif, involved in dimer formation of the transposase gene [41], was identified (data not shown) using the COILS program [26]. The conserved transposase-related DDE motif [41] was manually identified in the derived amino acid sequence as Dfv-55-sDngse-31-Esfngslr.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified a composite transposon (Tn6228) containing the complete genetic blueprint for degradation of 2,4-D and MCPA in a Sphingomonas sp. recently isolated from MCPA-degrading bacterial communities that originated from a herbicide-impacted groundwater aquifer [14]. This transposable element, which contains the catabolic genes cadAB in a novel genetic context, was situated on a conjugative plasmid. The plasmid contig, approximately 106 kbp in size, contains a single, perfectly identical copy of the IS3-element also present in the transposon contig. It was hypothesized that transposon Tn6228 would exist on the plasmid pCADAB1 flanked by identical IS3-elements, as well as in a circular intermediate state, typical of IS3-elements [39]. Due to the length of the transposase (1266 bp) being longer than the insert length in the Illumina library (500 bp), the assembler will not be able to solve the structure shown in Figure 1, where the transposon is inserted into the plasmid with IS3 elements flanking it. The structure displayed in Figure 1 was confirmed with PCR and product sequencing, using combinations (Table 2) of the primers shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The PCR product sequencing from PCR primer set 1 did not provide any eligible sequence, while sequencing of the products from PCRs 3 and 4 (Table 2) confirmed that the transposon is situated on pCADAB1 (data not shown). The failure of PCR and product sequencing with primer set 1 indicates that a scenario with only an IS3 element and not Tn6228 in the predicted position is not plausible. The fact that the catabolic genes are located on a conjugative plasmid is in good agreement with previous observations in xenobiotic-degrading sphingomonads [45].

Catabolic genes involved in degradation of MCPA

The well-studied tfdAα gene could not be found in the assembled contigs of Sphingomonas sp. ERG5. However, the alternative Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase (RO) cadAB genes were found within the composite transposon Tn6228 also harboring the remaining genes in the degradation pathway of 2,4-D and related compounds [42]. The 1347 bp cadA ORF shows very high amino acid similarity (99% identity) to the α-subunit of 2,4-D oxygenase from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 (accession no. BAH86807.1) and contains a Rieske motif and a catalytic domain, typical of RO enzymes. The 567 bp cadB ORF also shows high amino acid similarity (98% identity) to CadB from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1. β-subunits of RO oxygenases have been reported to be involved in substrate specificity [46].

In three-component RO-systems, a reductase receives electrons from NAD(P)H which is carried by a ferredoxin to the catabolic oxygenase, as reviewed in [47]. orf95 is predicted to encode a putative oxidoreductase protein. This ORF shows high similarity to orf1 from Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 (98% identity). orf98 is predicted to encode a Rieske ferredoxin component in the Rieske non-heme iron oxygenase (RO) family [48] and shows highest similarity (54% identity) to a 2-hydroxybenzoate 5-hydroxylase ferredoxin from Achromobacter piechaudii HLE (accession no. ZP_15933011.1). Even though all the parts of a three-component RO-system seem to be present in Sphingomonas sp. ERG5, the roles of the ferredoxin and oxidoreductase components in this RO system remain unknown, since it has previously been shown that the cadAB genes were necessary for conversion of 2,4-D to 2,4-DCP, but the oxidoreductase, putatively encoded by orf95, was not [8]. A ferredoxin component was not identified in the paper describing Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 [8], even though the sequence for a ferredoxin is present in the clone fragment in its GenBank entry (accession no. AB353895.1). The cadABC genes were first discovered in the strain Bradyrhizobium sp. HW3. Here it was shown that the ferredoxin component encoded by cadC indeed was essential for 2,4-D transformation, but no reductase was identified [2]. The finding of possible ferredoxin and reductase components of a three-component RO system in Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 suggests that these might be involved in the first catabolic step in 2,4-D and MCPA degradation, leading to the designation of putative cadC and putative novel gene cadD of the ferredoxin and reductase orfs, respectively.

Following the initial aryl ether linkage cleavage of MCPA and 2,4-D catalyzed by CadAB, the subsequent catabolic and regulatory pathway are represented by 8 ORFs in Tn6228: tfdB, tfdC, tfdD, tfdE, tfdF, tfdK, tfdR and cadR. These ORFs showed high amino acid similarity to previously described genes in the chlorophenoxyacetic acid metabolic pathway of strains Sphingobium herbicidovorans and Sphingomonas sp. TFD44 [42], [49] (Table S1). The tfd-genes are involved in the ortho cleavage pathway of 2,4-D and related compounds and were first studied in Cupriavidus pinatubonensis JMP134 [50]. The tfdB gene encodes a dichlorophenol hydroxylase, which converts 4-chloro-2-methylphenol (MCP) to 5-chloro-3-methyl-catechol (MCC), which is then converted to chloromuconate by a chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase, encoded by tfdC. The product of tfdD then transforms chloromuconate to dienelactone. Finally, dienelactone is converted first to maleylacetate then to 3-oxoadipate by the gene products of tfdE and tfdF, respectively.

Additionally, orf101 and orf102 encode subunits A and B of a 3-oxoadipate CoA-transferase, enabling the reaction yielding 3-oxoadipyl-CoA and succinate from 3-oxoadipate and succinyl-CoA. The 3-oxoadipate for this reaction could be provided by the reaction catalyzed by TfdF. orf103 is predicted to encode a 3-oxoadipyl CoA thiolase that can convert 3-oxoadipyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, both of which are further degraded the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) [51]. orf82 and orf84 are designated to encode a malate synthase G and a putative succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, respectively. Both of these enzymes are involved in the TCA and glyoxylate cycle; however homologs of these proteins were identified on chromosomal contigs (data not shown), suggesting that these plasmid-encoded enzymes are not essential for the host cell. Malate synthase G can convert acetyl-CoA into malate and succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase is possibly involved in the further degradation of succinyl-CoA.

In addition to the catabolic genes, regulatory genes cadR and tfdR as well as a gene encoding the transport protein TfdK are also present within the transposon. The deduced amino acid sequence of the cadR gene found here is 100% identical to that of Sphingobium herbicidovorans MH (accession no. CAF32814.1) and has an identity of 62% to the cad gene transcriptional regulator from Bradyrhizobium sp. HW13 (accession no. BAB78520.1). The cadR gene was found to be essential for 2,4-D degradation in Bradyrhizobium sp. HW13 and it was hypothesized, due to sequence similarity, that cadR encodes a positive transcriptional regulator [2].

orf90 was annotated as a LysR-type transcriptional regulator TfdR with high similarity (99% identity) to TfdR of Sphingomonas sp. TFD44 (accession no. AAT99366.1). It has been suggested that the transcriptional inducer of the 2,4-D pathway is the product of the TfdC protein, 2,4-dichloromuconate [52].

A homologue of the tfdK gene in Sphingobium herbicidovorans MH (accession no. CAF32820.1) encoding a protein of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) was found to be encoded by orf104. In Cupriavidus pinatubonensis JMP134 it was shown that TfdK is an active transporter of 2,4-D and increases its uptake rate of 2,4-D up to 10 times compared to a tfdK mutant [53].

Evolution of genetic elements

Two of the three gene clusters in Tn6228 previously described, showed high degrees of collinearity and sequence similarity to previous isolates [8], [42]. This could indicate that this specific genetic organization of the cad- and tfd-genes is highly conserved within sphingomonads capable of PAA-herbicide degradation or that these genes are an integral part of the genetic repertoire of sphingomonads. It has previously been discussed that sphingomonads harbor large numbers of mobile genetic elements [54] and that these are likely responsible for regular genetic exchange of biodegradative potential between sphingomonads [55]. The sequence conservation displayed in Figure 2 strongly supports that these catabolic enzymes are subject to HGT between sphingomonads. The non-collinearity between Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 and the gene cluster from Sphingobium herbicidorans MH could indicate that genetic rearrangements have occurred in one of the strains (Figure 2). The G+C values of Tn6228 shows that no internal regions with a markedly different G+C content are present within the transposon (Figure 1). However, when comparing with the plasmid backbone of pCADAB1, the region containing mobile genetic elements (including Tn6228) has a tendency towards slightly lower G+C contents. This suggests that the region with many mobile genetic elements might contain genes with an origin different from that of the plasmid backbone. Furthermore, the average G+C contents of pCADAB1 and Tn6228 are not different from that of the chromosomal contigs, suggesting that either these genetic entities were not recently acquired via horizontal gene transfer or that they originate from a bacteria with similar G+C content. Despite Sphingomonas sp. 58-1 being isolated in Japan, Sphingomonas sp. TFD44 being isolated in North America and Sphingomonas sp. ERG5 being isolated in Denmark, these strains show remarkable homology at the DNA level in the catabolic genes. All these were isolated from pesticide-polluted soils, and it would be interesting to attempt the isolation of cadAB-harboring sphingomonads from pristine environments for molecular comparisons in order to study the origin of this PAA degradation pathway initiated by the cad-genes.

Considering the phylogenetic separation of the CadA amino acid sequences shown in Figure 3 into a Sphingomonas and two Bradyrhizobium clades, it seems plausible that there exist multiple (at least three) classes of CadA that are each inherent to only the Sphingomonas or Bradyrhizobium genus. It was suggested that the Sphingomonas cluster and 2,4-D degrading Bradyrhizobium cluster had evolved from a shared ancestral gene, indicating different evolution of the cadA gene in 2,4-D degraders from that of non-2,4-D degraders [5]. Similar phylogenetic trees were constructed for the genes tfdBCDEFRK and cadR. The trees for tfdBD (Figures S1 and S2) contain monophyletic clades of the Sphingomonadaceae family, indicating that these genes are more similar within this family than with other phylogenetic groups (e.g. the Bradyrhizobiaceae family or Burkholderiales order). This suggests that parts of the 2,4-D-degradation pathway has evolved separately in the Sphingomonadaceae family, which is supported by others [9] who hypothesized that the tfdAα gene has evolved distinctly in sphingomonads and Bradyrhizobium without horizontal gene transfer. However, representatives of the downstream tfd-genes from Sphingomonadaceae are not yet abundant enough in the databases for proper evolutionary studies. The remaining phylogenetic trees suggest that horizontal gene transfer has had an effect on the evolution of the tfdCEFRK genes since no clear monophyletic groups are defined for any particular genera (data not shown).

The plasmid backbone of pCADAB1, encoding genes related to conjugative transfer and plasmid stability, showed high similarity and collinearity to plasmids pCAR3 (accession. no. AB270530.1) and pNL1 (accession. no. CP000676.1) from Sphingomonas sp. KA1 and Novosphingobium aromaticivorans DSM12444, respectively (Figure 1). Plasmid pNL1 has been shown to be able to transfer to other sphingomonads [45], and both pNL1 and pCAR3 have been suggested to be members of a novel incompatibility group of plasmids [43]. Though additional mating experiments should be carried out on this putatively novel incompatibility group, preliminary investigations on the plasmid replication and partitioning genes repA and parA of pCADAB1 indicates that this plasmid belongs to this group (data not shown). In fact, the backbones of the described plasmids are similar and collinear, while the region containing IS-elements and transposons is completely unrelated, suggesting that these mobile genetic elements might serve as the tools for acquiring new catabolic genes while the backbone is the unchangeable toolbox of these sphingomonad strains. It has been shown that many sphingomonad strains contain degradative plasmids [45]. If these plasmids are restricted to reside in members of the sphingomonad genera, it could explain why genes such as cadA evolve separately from other cadA-harboring genera. Further studies on the plasmids of sphingomonads will possibly provide insight to the degradative capabilities of these bacteria and why they apparently are successfully thriving in polluted environments.

Conclusions

In this study, a composite transposon was identified which harbors the complete set of genes for MCPA and 2,4-D degradation, including initial steps of the TCA cycle and regulatory genes. The transposon was furthermore found to be situated on a putatively conjugative plasmid. The pathway initiates with the CadAB Rieske non-heme iron monooxygenase, rather than the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase TfdA enzyme, that is most often associated with this pathway.

Supporting Information

Predicted ORFs with annotations and putative protein properties.

(DOCX)

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationship of representative TfdB sequences.

(TIF)

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationship of representative TfdD sequences.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank laboratory technicians Karin Pinholt Vestberg at University of Copenhagen and Pia Bach Jakobsen at GEUS for assistance.

Funding Statement

This study was partly funded by the Center for Environmental and Agricultural Microbiology - CREAM and the Lundbeck Foundation (www.lundbeckfoundation.com) project DK nr R44-A4384 (Lars Hestbjerg Hansen). CREAM is funded by the VILLUM FOUNDATION (www.villumfoundation.dk). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Thorling L, Hansen B, Langtofte C, Brüsch W, Møller RR, et al.. (2011) Grundvand. Status og udvikling 1989–2010. Teknisk rapport, GEUS 2011.

- 2. Kitagawa W, Takami S, Miyauchi K, Masai E, Kamagata Y, et al. (2002) Novel 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degradation genes from oligotrophic Bradyrhizobium sp. strain HW13 isolated from a pristine environment. J Bacteriol 184: 509–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fukumori F, Hausinger RP (1993) Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134 “2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate monooxygenase” is an alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase. J Bacteriol 175: 2083–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Streber WR, Timmis KN, Zenk MH (1987) Analysis, cloning, and high-level expression of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate monooxygenase gene tfdA of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134. J Bacteriol 169: 2950–2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Itoh K, Kanda R, Sumita Y, Kim H, Kamagata Y, et al. (2002) tfdA-like genes in 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading bacteria belonging to the Bradyrhizobium-Agromonas-Nitrobacter-Afipia cluster in alpha-Proteobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 3449–3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ledger T, Pieper DH, Perez-Pantoja D, Gonzalez B (2002) Novel insights into the interplay between peripheral reactions encoded by xyl genes and the chlorocatechol pathway encoded by tfd genes for the degradation of chlorobenzoates by Ralstonia eutropha JMP134. Microbiology 148: 3431–3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukumori F, Hausinger RP (1993) Purification and characterization of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate/alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase. J Biol Chem 268: 24311–24317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimojo M, Kawakami M, Amada K (2009) Analysis of genes encoding the 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading enzyme from Sphingomonas agrestis 58-1. J Biosci Bioeng 108: 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Itoh K, Tashiro Y, Uobe K, Kamagata Y, Suyama K, et al. (2004) Root nodule Bradyrhizobium spp. harbor tfdAalpha and cadA, homologous with genes encoding 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 2110–2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ditterich F, Poll C, Pagel H, Babin D, Smalla K, et al.. (2013) Succession of bacterial and fungal 4-chloro-2-methylphenoxyacetic acid degraders at the soil-litter interface. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. Kamagata Y, Fulthorpe RR, Tamura K, Takami H, Forney LJ, et al. (1997) Pristine environments harbor a new group of oligotrophic 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 2266–2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGowan C, Fulthorpe R, Wright A, Tiedje JM (1998) Evidence for interspecies gene transfer in the evolution of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degraders. Appl Environ Microbiol 64: 4089–4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huong NL, Itoh K, Suyama K (2007) Diversity of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T)-degrading bacteria in Vietnamese soils. Microbes and Environments 22: 243–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gözdereliler E, Boon N, Aamand J, De Roy K, Granitsiotis MS, et al. (2013) Comparing metabolic functionalities, community structures, and dynamics of herbicide-degrading communities cultivated with different substrate concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol 79: 367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindgreen S (2012) AdapterRemoval: easy cleaning of next-generation sequencing reads. BMC Res Notes 5: 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zerbino DR, Birney E (2008) Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 18: 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, et al. (2008) The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bateman A, Birney E, Durbin R, Eddy SR, Howe KL, et al. (2000) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nielsen P, Krogh A (2005) Large-scale prokaryotic gene prediction and comparison to genome annotation. Bioinformatics 21: 4322–4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Larsen TS, Krogh A (2003) EasyGene–a prokaryotic gene finder that ranks ORFs by statistical significance. BMC Bioinformatics 4: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J (2009) DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics 25: 119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rasko DA, Rosovitz MJ, Okstad OA, Fouts DE, Jiang L, et al. (2007) Complete sequence analysis of novel plasmids from emetic and periodontal Bacillus cereus isolates reveals a common evolutionary history among the B. cereus-group plasmids, including Bacillus anthracis pXO1. J Bacteriol 189: 52–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M (2006) ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34: D32–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A (2000) EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet 16: 276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J (1991) Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252: 1162–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA (2011) Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27: 1009–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inkscape website. Available: http://www.inkscape.org. Accessed 2013 Jul 4.

- 29. Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, et al. (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res 36: W465–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J (2000) T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 17: 540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci 8: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guindon S, Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52: 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Anisimova M, Gascuel O (2006) Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst Biol 55: 539–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1596–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, et al. (2012) Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 13: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nojiri H, Shintani M, Omori T (2004) Divergence of mobile genetic elements involved in the distribution of xenobiotic-catabolic capacity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64: 154–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nagarajan N, Pop M (2013) Sequence assembly demystified. Nat Rev Genet 14: 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sekine Y, Aihara K, Ohtsubo E (1999) Linearization and transposition of circular molecules of insertion sequence IS3. J Mol Biol 294: 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Curcio MJ, Derbyshire KM (2003) The outs and ins of transposition: from mu to kangaroo. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 865–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ohtsubo E, Minematsu H, Tsuchida K, Ohtsubo H, Sekine Y (2004) Intermediate molecules generated by transposase in the pathways of transposition of bacterial insertion element IS3. Adv Biophys 38: 125–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thiel M, Kaschabek SR, Groning J, Mau M, Schlomann M (2005) Two unusual chlorocatechol catabolic gene clusters in Sphingomonas sp. TFD44. Arch Microbiol 183: 80–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shintani M, Urata M, Inoue K, Eto K, Habe H, et al. (2007) The Sphingomonas plasmid pCAR3 is involved in complete mineralization of carbazole. J Bacteriol 189: 2007–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Romine MF, Stillwell LC, Wong KK, Thurston SJ, Sisk EC, et al. (1999) Complete sequence of a 184-kilobase catabolic plasmid from Sphingomonas aromaticivorans F199. J Bacteriol 181: 1585–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Basta T, Keck A, Klein J, Stolz A (2004) Detection and characterization of conjugative degradative plasmids in xenobiotic-degrading Sphingomonas strains. J Bacteriol 186: 3862–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hurtubise Y, Barriault D, Sylvestre M (1998) Involvement of the terminal oxygenase beta subunit in the biphenyl dioxygenase reactivity pattern toward chlorobiphenyls. J Bacteriol 180: 5828–5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ferraro DJ, Gakhar L, Ramaswamy S (2005) Rieske business: structure-function of Rieske non-heme oxygenases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338: 175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gibson DT, Parales RE (2000) Aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases in environmental biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 11: 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muller TA, Byrde SM, Werlen C, van der Meer JR, Kohler HP (2004) Genetic analysis of phenoxyalkanoic acid degradation in Sphingomonas herbicidovorans MH. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 6066–6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Don RH, Weightman AJ, Knackmuss HJ, Timmis KN (1985) Transposon mutagenesis and cloning analysis of the pathways for degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 3-chlorobenzoate in Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134(pJP4). J Bacteriol 161: 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harwood CS, Parales RE (1996) The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu Rev Microbiol 50: 553–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Filer K, Harker AR (1997) Identification of the Inducing Agent of the 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic Acid Pathway Encoded by Plasmid pJP4. Appl Environ Microbiol 63: 317–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leveau JH, Zehnder AJ, van der MeerJR (1998) The tfdK gene product facilitates uptake of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate by Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4). J Bacteriol 180: 2237–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aylward FO, McDonald BR, Adams SM, Valenzuela A, Schmidt RA, et al.. (2013) Comparison of 26 Sphingomonad Genomes Reveals Diverse Environmental Adaptations and Biodegradative Capabilities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55. Stolz A (2009) Molecular characteristics of xenobiotic-degrading sphingomonads. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81: 793–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Predicted ORFs with annotations and putative protein properties.

(DOCX)

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationship of representative TfdB sequences.

(TIF)

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationship of representative TfdD sequences.

(TIF)