Abstract

Two decades after a worldwide vaccination campaign was used to successfully eradicate naturally occurring smallpox, the threat of bioterrorism has led to renewed vaccination programs. In addition, sporadic outbreaks of human monkeypox in Africa and a recent outbreak of human monkeypox in the U.S. have made it clear that naturally occurring zoonotic orthopoxvirus diseases remain a public health concern. Much of the threat posed by orthopoxviruses could be eliminated by vaccination; however, because the smallpox vaccine is a live orthopoxvirus vaccine (vaccinia virus) administered to the skin, the vaccine itself can pose a serious health risk. Here, we demonstrate that rhesus macaques vaccinated with a DNA vaccine consisting of four vaccinia virus genes (L1R, A27L, A33R, and B5R) were protected from severe disease after an otherwise lethal challenge with monkeypox virus. Animals vaccinated with a single gene (L1R) which encodes a target of neutralizing antibodies developed severe disease but survived. This is the first demonstration that a subunit vaccine approach to smallpox-monkeypox immunization is feasible.

Due to concerns about the possible use of smallpox as a biological weapon, programs to vaccinate 500,000 military personnel (mandatory) and a similar number of health care workers (voluntary) were implemented in December 2002. The smallpox vaccine used in these programs—calf lymph-derived live vaccinia virus (VACV) administered by scarification with a bifurcated needle—is essentially the same vaccine first used >2 centuries ago (27). A comparable smallpox vaccine consisting of clonal VACV grown in cell culture is being tested in clinical trials (29). Although VACV is highly immunogenic and is known to confer long-lasting protective immunity to smallpox (12), the adverse events associated with the present smallpox vaccine (i.e., Dryvax) pose a significant obstacle to successful vaccination campaigns. Adverse events historically associated with VACV range from the nonserious (e.g., fever, rash, headache, pain, and fatigue) to life threatening (e.g., eczema vaccinatum, encephalitis, and progressive vaccinia) (6). Serious adverse events that are not necessarily causally associated with vaccination, including myocarditis and/or myopericarditis, have been reported during past and present smallpox vaccination programs (4, 9). Several adverse cardiac events reported in the first 4 months of the 2003 civilian and military vaccination campaigns prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to revise their recommendations for exclusion of potential smallpox recipients to include those persons with heart disease or several other conditions (3). Moreover, the live VACV vaccines are problematic because lesion-associated virus at the site of vaccination is infectious and can be inadvertently spread to other parts of the body (e.g., ocular autoinoculation) and to other individuals (i.e., contact vaccinia) (6).

Although the recent smallpox vaccination programs are intended to protect against bioterror events, naturally occurring poxvirus diseases are also a growing concern because the number of persons with vaccinia virus-induced immunity has been in decline. Epidemics of human monkeypox have occurred sporadically in west and central Africa (16, 18a), and very recently, an outbreak of human monkeypox occurred in the midwestern United States (2). This outbreak (71 suspected and 35 laboratory-confirmed cases as of 8 July 2003) may have been transmitted from prairie dogs that were infected after being housed close to an imported African rodent (5). The first monkeypox outbreak outside Africa coupled with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) pandemic illustrates how rare zoonotic viral diseases can emerge rapidly and spread in unprotected populations.

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that vaccination with VACV protects humans against smallpox and monkeypox (10a, 18a). All viruses in the genus Orthopoxvirus, family Poxviridae, including VACV, monkeypox virus (MPOV), and variola virus (the virus that causes smallpox), are highly similar in the majority of their nearly 200 proteins, which accounts superficially for the cross-protection among these viruses (28). However, the precise immune mechanisms by which the smallpox vaccine elicits immunity to monkeypox and smallpox remain largely unknown. Identifying protective and problematic immunogens will be essential for developing, testing, and bridging next-generation smallpox vaccines. In addition, identifying protective immunogens might allow the development of a subunit smallpox vaccine that affords protection with negligible adverse events.

Previously, we used a gene gun-delivered DNA vaccine approach to test several VACV genes and gene combinations for immunogenicity and protective efficacy in mice (13, 14). A four-gene combination DNA vaccine (hereafter referred to as 4pox DNA vaccine) protected 100% of mice challenged with a lethal dose of VACV and was immunogenic in nonhuman primates (13). There are two major forms of infectious orthopoxvirus: the intracellular mature virion (IMV), which is infectious when released from disrupted cells, and the extracellular enveloped virion (EEV), which buds from infected cells (10a, 23). The 4pox DNA vaccine contained two IMV-specific genes (L1R and A27L) and two EEV-specific genes (A33R and B5R). The L1R and A27L immunogens are known targets of IMV neutralizing antibodies (25, 26, 30). Antibodies to the B5R (but not A33R) immunogen reportedly neutralize EEV (11, 20). The A33R immunogen is a target of antibody-dependent, complement-mediated cytolysis (A. L. Schmaljohn, unpublished observations). We hypothesize that the high level of protection conferred when combinations of IMV and EEV immunogens are used is due to the targeting of different forms of the virus (e.g., IMV and EEV) at different stages of infection and by different mechanisms. Here, we report the results of a challenge experiment in which we tested the capacity of the 4pox DNA vaccine to protect rhesus macaques from severe monkeypox.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

The VACV Connaught vaccine strain (derived from the New York City Board of Health strain) (21) was maintained in Vero cell (ATCC CRL-1587) monolayers grown in Eagle minimal essential medium containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% antibiotics (100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, and 50 μg of gentamicin/ml), and 10 mM HEPES (cEMEM). COS cells (ATCC CRL 1651) were used for transient-expression experiments. A working stock of MPOV Zaire-79 (MPOV-Z79) at 5 × 108 PFU per ml was generously provided by J. Huggins.

Gene gun vaccination.

Rhesus macaques were vaccinated using the same DNA vaccine plasmids and gene gun conditions described previously (13, 14).

VACV-infected-cell lysate ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed as described previously (13).

VACV and MPOV PRNT.

Plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT) were performed on Vero cells as described previously (13).

RIPA.

Radioimmunoprecipitation assays (RIPAs) were performed as described previously (13).

Intravenous challenge with MPOV.

Rhesus macaques were anesthetized using telezol at 3 to 6 mg/kg of body weight or ketamine at 10 to 20 mg/kg. MPOV sonicated for 30 s on ice and diluted in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium containing 1% FBS was injected (1 ml) into the saphenous vein using a 20- to 22-gauge catheter, followed by 3 ml of saline to flush the injection site. On the indicated days, monkeys were anesthetized and weighed, and blood was drawn from the femoral vein using a 22-gauge needle and vacutainer tube. Pulse and oximetery were measured using a handheld digital pulse oximeter (SurgiVet, Inc., Waukesha, Wis.). Hematological values of fresh whole blood were determined using a Coulter (Miami, Fla.) AcT series analyzer. Serum samples were stored at −70°C before blood chemistry values were determined using a Piccolo Point-of-Care chemistry analyzer (Abaxis, Inc., Union City, Calif.).

Whole-blood processing for plaque assay.

Approximately 300 μl of blood collected in K2 EDTA vacutainer tubes was transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, rapidly freeze-thawed three times, and then spun in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 s to pellet cell debris. The supernatants were sonicated for 30 s on ice and then assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers starting at a 1:100 dilution in cEMEM. The monolayers were stained 5 days postinfection with 1% crystal violet in 70% ethanol.

Throat swab processing for plaque assay.

Sterile swabs were used to collect throat specimens. The swabs were stored at −70°C until further use. The swabs were placed in 300 μl of medium, allowed to soak for ∼5 s, and then swirled to allow release of swabbed material into the medium. Throat swab suspensions were subjected to three rapid freeze-thaw cycles and spun in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 × g for 5 s to pellet cell debris. The supernatants were sonicated for 30 s on ice and then assayed for infectious virus by plaque assay on Vero cell monolayers starting at a 1:10 dilution in cEMEM. The monolayers were stained 5 days postinfection with 1% crystal violet in 70% ethanol.

TaqMan PCR of whole blood.

DNA was extracted from frozen blood samples by using the Aquapure DNA kit (Bio-Rad) as described previously (17). Prior experiments had demonstrated that the material was noninfectious after a 60-min incubation at 55°C in Aquapure lysis buffer.

OPXJ7R3U (5′-TCATCTGGAGAATCCACAACA-3′) and OPXJ7R3L (5′-CATCATTGGCGGTTGATTTA-3′) and the probe OPXJ7R3P (5′-CTGTAGTGTATGAGACAGTGTCTGTGAC-3′) were selected from the variola virus hemagglutinin gene (GenBank no. L22579; open reading frame J7R). The primers were synthesized by using standard phosphoramidite chemistry with an ABI 394 DNA-RNA synthesizer. The TaqMan probe was synthesized by PE Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.) and contained 6-carboxyfluorescein in the 5′ end and 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine and a phosphate in the 3′ end.

5′ nuclease PCR assay.

The 5′ nuclease PCR and amplification conditions were carried out using Platinum Quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) as described previously (17). All reactions included at least one positive control that contained 5 fg (∼25 copies) of MPOV genomic DNA and one no-template control. The 5-fg positive control for each run established the threshold cycle (Ct) value for positivity. Samples yielding Ct values which marginally exceeded the threshold value were retested. If the Ct value was confirmed to exceed the threshold after retesting, the sample was considered negative (i.e., the sample contained <25 gene copies).

Construction of Escherichia coli expression plasmids containing VACV L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L genes.

The genes coding for L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L from VACV strain Connaught were amplified from constructs described previously (13, 14) using PCR and Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. The primer sets used (5′-GGCATATGGGTGCCGCAGCAAGC-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTCAGTTTTGCATATCCG-3′, 5′-GGCATATGATGACACCAGAAAACG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTTAGTTCATTGTTTTAACAC-3′, 5′-GGCATATGAAAACGATTTCCGTTGTTACG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGTTACGGTAGCAATTTATGG-3′, and 5′-GGCCATGGACGGAACTCTTTTCCCCG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTCATATGGACGCCGTCC-3′) were complementary to the 5′ and 3′ ends of the gene sequences (italics) of VACV L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L, respectively, and contained the recognition sites for the restriction enzymes NdeI, NcoI, and XhoI (underlined). The amplicons obtained from the PCRs were cloned directly into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer, and the resulting clones were screened by restriction analysis. Plasmid DNA containing the desired VACV inserts was digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (NdeI and XhoI for L1R, A33R, and B5R; NcoI and XhoI for A27L). The inserts digested with NdeI and XhoI were subcloned into pET-16b, and the inserts digested with NcoI and XhoI were subcloned into pET-21b. The VACV genes in the final constructs, pET-L1R(VACV), pET-A33R(VACV), pET-B5R(VACV), and pET-A27L(VACV), were sequenced using a model 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) to ensure that no changes had occurred during subcloning procedures.

Expression of the vaccinia virus L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L proteins in E. coli.

The A33R, B5R, and A27L proteins were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RP-X (Stratagene). The L1R protein was expressed under the same conditions as the aforementioned proteins; however, the L1R protein was expressed in the E. coli strain Rosetta-gami(DE3) (Novagen). Competent cells were transformed with either pET-L1R(VACV), pET-A33R(VACV), pET-B5R(VACV), or pET-A27L(VACV) and selected for growth on Luria broth (LB)-ampicillin plates. Individual colonies were used to inoculate a 100-ml LB culture containing carbenicillin (50 μg/ml). The cells were grown to saturation at 37°C and used to inoculate 3 liters of LB containing carbenicillin (50 μg/ml). The cells were grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.6; VACV protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (final concentration, 1 mM) for 3 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min) and resuspended to a density of 0.2 g/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl-0.1% NP-40-5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Cells expressing L1R protein were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-150 mM NaCl-0.1% NP-40. The cells were rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C.

Purification of VACV L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L proteins.

All protein preparations were treated identically with the following exceptions: the L1R protein was purified in the complete absence of β-mercaptoethanol, and the A27L protein was purified using a 5-ml HiTrap chelating HP column (Amersham Biosciences). Frozen cell suspensions were quickly thawed in a 25°C water bath. Thawed suspensions were treated with rLysozyme (final concentration, 7.5 kU/ml) (Novagen) and rocked for 20 min at room temperature. The following purification steps were carried out at 4°C. Suspensions were lysed by sonication using a Branson model 450 sonifier with the microtip attachment and centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 1.5 h. The pellets were discarded, and the supernatants were dialyzed overnight against 2 liters of P buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.5]-500 mM NaCl-5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The dialysates were clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 1 h. Prior to being loaded, individual 1-ml HiTrap chelating HP columns were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and equilibrated with P buffer. Separate columns were loaded with lysates containing L1R, A33R, B5R, or A27L protein and washed with 5 column volumes of P buffer and then with 5 column volumes of P buffer plus 50 mM imidazole. The L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L proteins were eluted with P buffer plus 500 mM imidazole to yield the final fractions. VACV protein-containing fractions were identified by Western analysis using monoclonal antibodies specific for pentahistidine or VACV L1R, A33R, or A27L protein. The concentrations of these partially purified VACV proteins were determined by UV absorbance at 280 nm using the extinction coefficients 1.52, 0.87, 0.82, and 8.27 A280 mg−1 ml · cm−1, which were calculated from the amino acid sequences of the L1R, A33R, B5R, and A27L proteins, respectively.

Immunogen-specific ELISA.

Histidine-tagged VACV A27L, L1R, B5R, and A33R proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified from E. coli using the methods described above. Antigen diluted in 0.1 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6, was used to coat 96-well ELISA plates (100 μl per well). The concentrations of purified A27L, L1R, B5R, and A33R proteins used were 50, 250, 50, and 100 ng/well, respectively. Purified histidine-tagged human Tsg101 protein or a truncated hantavirus nucleocapsid was used as a negative control antigen. Antigen was adsorbed to the ELISA plates overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed one time with PBS plus 0.05% Tween 20 (wash buffer), blocked for 1 h at 37°C with wash buffer containing 5% FBS plus 3% goat serum (blocking buffer), washed once, and incubated for 1 h at 37°C with antibody diluted in blocking buffer containing 20 μg of E. coli lysate/ml to reduce background. The plates were washed three times, incubated for 1 h at 37°C with peroxidase-labeled goat-anti-monkey immunoglobulin G (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) diluted in blocking buffer, washed as before, and incubated in 100 μl of 2,2′-azino-di(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) substrate/well. After 10 to 30 min at room temperature, the colorimetric reaction was stopped by the addition of 100 μl of 0.2 N phosphoric acid/well. The optical density (OD) at 405 nm was determined by an ELISA plate reader. Nonspecific binding was controlled for by subtracting OD values obtained on negative control antigen from OD values obtained on purified VACV antigens. End point titers were determined as the highest dilution with an OD greater than the mean OD value from negative control serum sample wells (1:50 dilution) plus 2 standard deviations.

Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adhered to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (23a). The facility where this research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Booster DNA vaccination and challenge with MPOV.

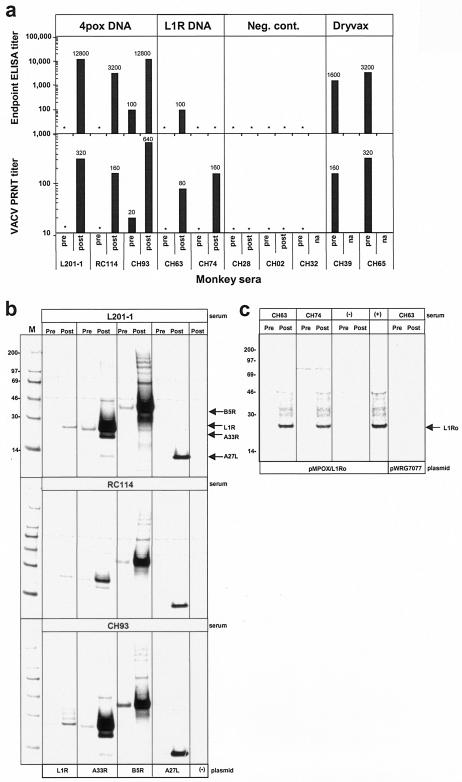

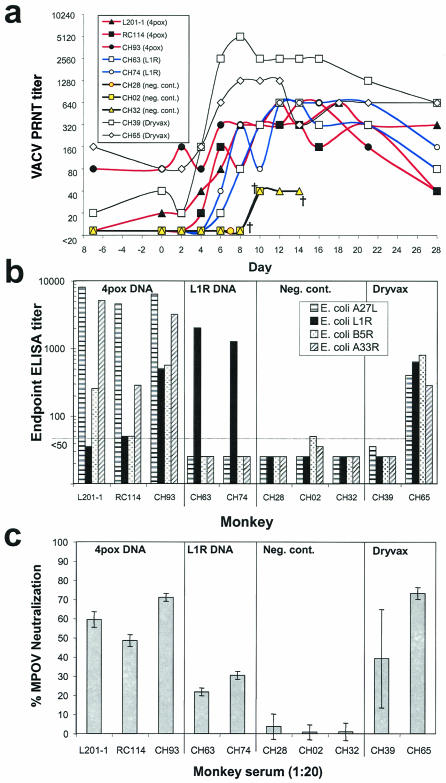

The challenge experiment included four groups: group 1 consisted of three monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine, group 2 consisted of two monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine, group 3 (negative controls) consisted of three monkeys vaccinated with a Hantaan virus DNA vaccine (13, 15), and group 4 (positive controls) consisted of two monkeys vaccinated with the human smallpox vaccine (Dryvax). The L1R DNA vaccine was tested to determine the degree to which vaccination with a single immunogen eliciting IMV-neutralizing antibodies could confer protection. The DNA vaccines were administered by gene gun. The identification numbers, sexes, weights, and vaccination histories of the monkeys are shown along with summarized challenge result data in Table 1. Five weeks before challenge, all monkeys except the monkeys vaccinated with Dryvax and one of the negative controls (CH32) were vaccinated with new preparations of the same DNA vaccine they had received 1 to 2 years earlier. This booster vaccination was administered to affirm that immunological memory had been elicited by the initial vaccination series and to ensure robust responses to the DNA vaccines with the intent to prove concepts rather than explore minimal requirements for protection. Sera collected at the time of boosting and 11 days later were evaluated for anamnestic antibody responses by ELISA, PRNT, and RIPA (Fig. 1). Before the DNA vaccine boost, all sera except CH93 had undetectable levels of antibody as measured by VACV-infected-cell lysate ELISA and PRNT (Fig. 1a). After the boost, all of the monkeys in groups 1 and 2 had detectable levels of neutralizing antibodies and all except CH74 were positive by ELISA. Gene-specific RIPA indicated that the three monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine had increased levels of antibody against each of the four immunogens (Fig. 1b). Sera from the two monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine had elevated levels of L1R-specific antibody after the boost (Fig. 1c). Thus, gene gun vaccination with the 4pox DNA vaccine or the L1R DNA vaccine elicited a memory response that was maintained for at least a year and up to 2 years (i.e., monkey L201-1).

TABLE 1.

Rhesus macaques used in MPOV i.v. challenge: vaccination history and challenge outcome

| Process | IDa | Sex/wt (kg)b | Vaccinec | Vaccination (wk)

|

Challenge (PFU) | Challenge outcome

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial series | Boostd | No. of lesionse | Disease severity | Day of death postchallenge | |||||

| Dosing expt | CH42 | F/5.8 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 11 | ND | 5 × 108 | 0 | Gravef | 6 |

| CH03 | F/4.5 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 11 | ND | 5 × 108 | 0 | Gravef | 6 | |

| CH85 | F/4.8 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 12 | ND | 5 × 106 | 198 | Severe | Survived | |

| CH64 | F/5.5 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 12 | ND | 5 × 106 | 125 | Severe | Survived | |

| Vaccine evaluation | L201-1 | M/8.4 | 4pox DNA | 0, 3, 6, 11 | 121 | 2 × 107 | 13 | Mild | Survived |

| RC114 | F/4.0 | 4pox DNA | 0, 3, 6, 12 | 59 | 2 × 107 | 30 | Moderate | Survived | |

| CH93 | F/4.1 | 4pox DNA | 0, 3, 6, 12 | 59 | 2 × 107 | 1 | Mild | Survived | |

| CH63 | F/4.0 | L1R DNA | 0, 3, 6, 12 | 59 | 2 × 107 | 100 | Severe | Survived | |

| CH74 | F/4.5 | L1R DNA | 0, 3, 6, 12 | 59 | 2 × 107 | 212 | Severe | Survived | |

| CH28 | F/5.3 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 11 | 59 | 2 × 107 | TNTC | Graveg | 7 | |

| CH02 | F/4.7 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 11 | 59 | 2 × 107 | TNTC | Grave | 10 | |

| CH32 | F/4.5 | Neg. cont. | 0, 3, 6, 11 | ND | 2 × 107 | TNTC | Grave | 14 | |

| CH39 | F/4.1 | Dryvax | 0 | ND | 2 × 107 | 0 | No disease | Survived | |

| CH65 | F/3.8 | Dryvax | 0 | ND | 2 × 107 | 0 | No disease | Survived | |

ID, monkey identification number.

F, female; M, male.

Neg. cont., negative control DNA vaccine.

ND, not done.

TNTC, too numerous to count.

Hemorrhagic monkeypox.

Hemorrhagic monkeypox progressing to disseminated exanthem.

FIG. 1.

Memory antibody response to vaccination with poxvirus DNA vaccines. (a) Sera from rhesus macaques previously (1 to 2 years) vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine, L1R DNA vaccine, negative control (Neg. cont.) DNA vaccine, or Dryvax collected immediately before (pre) and 11 days after (post) a booster vaccination were evaluated for anti-VACV antibodies by ELISA using VACV-infected-cell lysate antigen and VACV PRNT. ELISA end point and PRNT50 titers are shown. *, ELISA titer of <100 or PRNT titer of <20. na, not applicable because there was no boost. (b) Pre- and postboost sera from three monkeys (L201-1, RC114, and CH93) vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine were tested for immunogen-specific antibodies by RIPA using lysates from COS cells transfected with plasmids expressing the four VACV genes that comprise the 4pox DNA vaccine: pWRG/L1R, pWRG/A33R, pWRG/B5R, and pWRG/A27L. Lysate from COS cells transfected with empty-vector plasmid (pWRG7077) was used as a negative control antigen (−). (c) Pre- and postboost sera from two monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine (CH63 and CH74) were tested for L1R-specific antibodies by RIPA using lysates from COS cells transfected with a plasmid, pMPOX/L1Ro, expressing the MPOV L1R orthologous protein, L1Ro (13). Serum from a monkey (CH02) vaccinated with a negative control plasmid and serum from a monkey (CH63) vaccinated with pWRG/L1R collected after the initial series of vaccinations (9) were used as negative (−) and positive (+) controls, respectively. Lysate from COS cells transfected with the empty vector pWRG7077 served as a negative control antigen. Molecular mass markers (M) are shown in kilodaltons on the left, and the positions of immunoprecipitated VACV proteins are shown on the right.

Dosing experiment results.

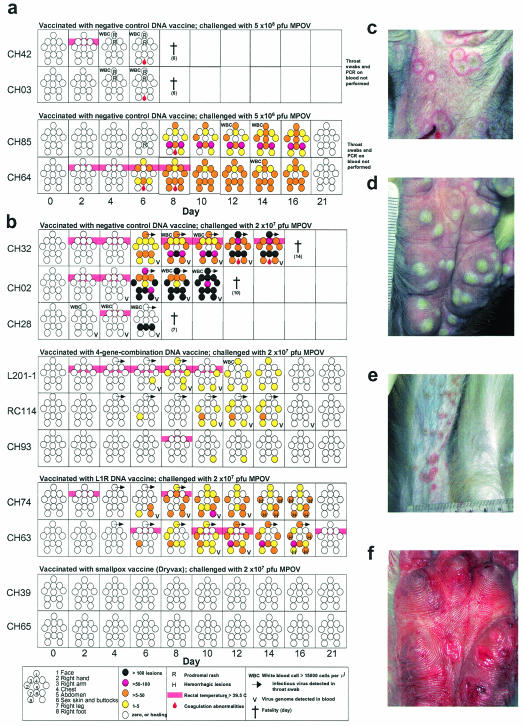

Before the challenge experiment, two dosing experiments were performed to (i) extend to this MPOV isolate the previous reports (22, 24) that MPOV causes severe monkeypox when administered by the intravenous (i.v.) route and (ii) determine the dose of MPOV-Z79 sufficient to cause severe, but not overwhelming, disease. In the first experiment, two rhesus macaques were injected i.v. with a high dose (5 × 108 PFU) of MPOV-Z79. This dose caused organ-hemorrhagic monkeypox, and the animals died on day 6 before presenting generalized exanthema. The likely cause of death was cardiovascular collapse secondary to multiple organ failure (e.g., liver) exacerbated by a bleeding diathesis and inability to recover from anesthesia. In the second experiment, two rhesus macaques were injected i.v. with 5 × 106 PFU. A rash erupted on day 6 and progressed to disseminated exanthema with >100 lesions per animal. The animals survived with only minor scarring. Clinical manifestations on the days following the high- and low-dose challenges are shown in Fig. 2a and Table 1. By the World Health Organization scoring system used during the smallpox eradication program, <25 lesions represented mild disease, 25 to 99 lesions represented moderate disease, 100 to 250 lesions represented severe disease, and >250 lesions represented grave disease. Thus, 5 × 106 PFU is sufficient to cause severe monkeypox and 5 × 108 PFU causes a hemorrhagic manifestation of the disease that is rapidly fatal and does not resemble naturally occurring monkeypox or smallpox.

FIG. 2.

Evolution of disease in rhesus macaques challenged i.v. with MPOV. (a) Monkeys vaccinated with negative control DNA vaccines were injected (day 0) with a high or low dose of MPOV-Z79. Graphic representations of rash distribution, lesion number, fever, elevated white blood cell counts, and bleeding disorders over 3 weeks are shown. (b) Monkeys vaccinated with a negative control DNA vaccine, 4pox DNA vaccine, L1R DNA vaccine, or Dryvax were injected (day 0) with 2 × 107 PFU of MPOV-Z79. Throat swab and blood viremia data are included in panel b but not in panel a. (c) Umbilicated lesions on face (monkey CH32; day 10 after challenge) 6 days after onset of rash. (d) Deep pustular lesions on CH74 palm (day 10). (e) Disproportionate number of lesions on leg injected with virus (monkey CH63; day 14). (f) Bleeding lesions on CH74 palm (day 14) 8 days after onset of rash.

Monkeypox challenge.

Based on the dosing experiments (Fig. 2a), a dose of 2 × 107 PFU was chosen for the vaccine evaluation experiment. Vaccinated monkeys were challenged with MPOV-Z79 by i.v. injection into the right or left saphenous vein. At 2-day intervals, whole-blood, serum, and throat swab samples were collected, and rectal temperature, pulse, and blood oxygen saturation were measured. Salient clinical and laboratory findings are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2b (also see Fig. 4). Monkeys vaccinated with the negative control DNA vaccine developed grave monkeypox and succumbed on days 7, 10, and 14. Monkeys vaccinated with Dryvax showed no signs of clinical disease, indicating that VACV given more than a year earlier could confer protective immunity against this robust MPOV challenge dose. This confirms earlier findings that vaccination of rhesus macaques with a commercial smallpox vaccine confers protection against monkeypox after i.v. challenge (22). Monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine developed severe monkeypox and atypical lesions, but the animals recovered. This suggested that vaccination with L1R alone can confer some protection against monkeypox. The most important finding of this study was that monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine were protected not only from lethal monkeypox but also from severe disease (Fig. 2b and Table 1). This is the first demonstration that vaccination with a combination of VACV immunogens, rather than the whole infectious virus, is sufficient to protect nonhuman primates against any poxvirus disease.

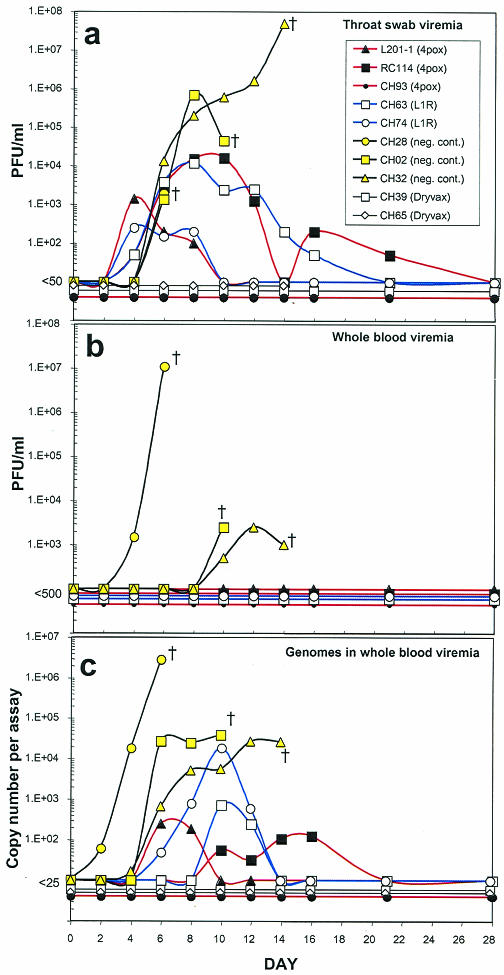

FIG. 4.

Time courses of viremia in vaccinated and control monkeys challenged with MPOV. (a) Infectious MPOV detected in throat swabs. (b) Infectious virus detected in whole blood by plaque assay. (c) MPOV genomes detected in whole blood by TaqMan PCR. Monkeys were challenged with MPOV on day 0. †, fatality.

The cause of death for the negative control monkey (CH28) that died on day 7 was similar to that of the two monkeys (CH42 and CH03) that had received a high dose of virus (i.e., organ-hemorrhagic monkeypox). There was evidence of hemorrhage in the lymph nodes, heart, lungs, urinary bladder, uterus, and digestive tract. In addition, there were hepatopathy, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, diffuse pulmonary edema, and degeneration or necrosis of the bone marrow. Unlike the high-dose recipients, CH28 showed signs of progression to severe exanthematous monkeypox. The monkeys that died on days 10 and 14, CH02 and CH32, respectively, presented a disseminated exanthematous rash, marked lymphadenopathy (up to 20 times normal size), mild splenomegaly, mild pulmonary edema, and a notable absence of remarkable pathology in other organs. Except for lymphadenopathy, which is a clinical symptom of monkeypox (18), the necropsy findings are similar to those of autopsies of human smallpox fatalities where none of the vital organs appeared to be severely damaged and death was attributed to “toxemia” (10a).

The most dramatic clinical manifestation of monkeypox in the challenged monkeys, other than death, was the generalized vesiculopustular rash. The rash was first evident 6 days postchallenge and progressed from macules to papules, to vesicles, to pustules, and finally to crusts over 10 days. The crusts fell off, in some cases leaving scars. As in naturally occurring human monkeypox and smallpox, the distribution of lesions was primarily on the face (Fig. 2c) and hands (Fig. 2d) but rarely on the abdomen. The sex skin, nipples, and buttocks were also commonly affected. In three monkeys (RC114, CH74, and CH63), the area of the leg surrounding the site of i.v. injection was a region with a relatively high number of lesions (Fig. 2b). For example, 52 of the 100 lesions on CH63 were distributed on the injected leg with fewer than five on the other leg (Fig. 2e). We suspect that seeding of the tissues surrounding the site of injection occurred at the time of injection, possibly by a small amount of inoculum that missed the saphenous vein and entered blood or lymph capillaries. Although it became easier to count lesions as they progressed from macules to crusts, there was only one crop of lesions, which differentiates orthopoxvirus-associated rash from other viral-infection-associated rashes, such as chickenpox. The temporal distribution of lesions during the disease course is shown in Fig. 2b.

One notable difference between the monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine and all other monkeys in this study was bleeding into the lesions beginning on day 14 (Fig. 2b and f). Hemorrhage appeared to occur from below the pustules, and the lesions would flatten. This phenomenon was reminiscent of reports of late-hemorrhagic-type smallpox in persons who had been successfully vaccinated with VACV (10). By day 21, the lesions on the face, feet, and hands of CH63 and CH74 were rapidly healing, and the monkeys recovered. This is in contrast to hemorrhagic smallpox in humans, which was almost always fatal. Due to the small number of animals in this experiment, it is unclear if the hemorrhagic lesions are a normal variation of late-stage monkeypox-associated rash in rhesus macaques or somehow linked to preexisting L1R-specific immunity.

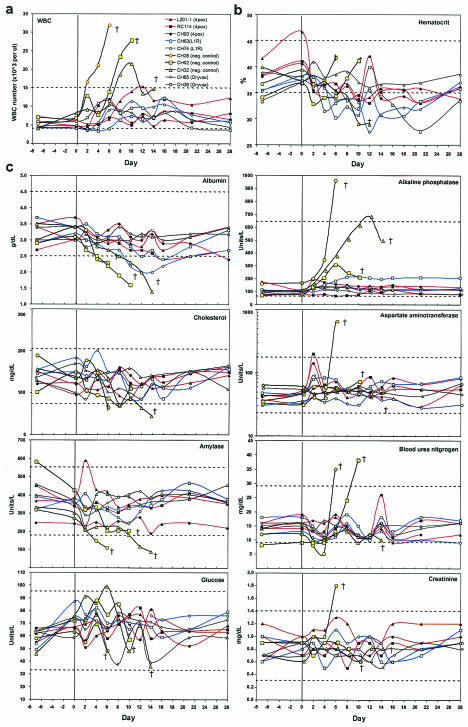

Aside from the dramatic rash, other symptoms of disease in all three negative control animals included fever (≥39.5°C) on days 2 and/or 4 after challenge (Fig. 2b) and elevated white blood cell counts (Fig. 3a). Except for a trend toward low (<35%) hematocrit in most of the monkeys (Fig. 3b), there were no consistent alterations in other parameters, including weight, pulse, blood oxygen saturation, and platelet numbers, for any groups during the course of the study (data not shown). Analysis of blood chemistry indicated that one or more of the negative control animals exhibited abnormal levels of analytes consistent with the hepatopathy (Fig. 3c).

FIG. 3.

Abnormal hematological findings in immunized and control monkeys challenged with MPOV. (a and b) Automated cell counts of whole blood were determined; white blood cell (WBC) counts (a) and hematocrit (b) are shown. (c) Serum clinical chemistries. Monkeys were challenged on day 0 (bold vertical line). The dashed lines indicate normal high and low values for rhesus macaques. †, fatality.

As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2b and 3, the monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine had very mild or, in the case of CH93, almost nonexistent clinical or laboratory indications of monkeypox. Note that the lesions that did develop in the group vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine not only were fewer but also healed more rapidly than those in the low-dose group (Fig. 2a) or the L1R DNA vaccine group (Fig. 2b). The two monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine were clinically normal with the following exceptions: CH74 had 212 lesions, a fever on days 2 and 8, and a sustained decrease in albumin on days 12 to 16, and CH63 had 100 lesions, an intermittent fever from days 6 thru 28, and a transient decrease in albumin on day 16. The two monkeys vaccinated with Dryvax did not present any signs of disease after challenge.

Virus shedding in protected and unprotected animals.

To determine if the positive control vaccine, Dryvax, or any of the candidate DNA vaccines prevented virus shedding, plaque assays were performed on processed throat swab suspensions. The results are shown in Fig. 2 and 4a. No infectious viruses were detected in the oral secretions of the two monkeys vaccinated with Dryvax. Similarly, no infectious viruses were detected in monkey CH93, which was vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine. The other two monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine and both monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine had infectious virus in oral secretions starting 4 days after challenge. Interestingly, infectious viruses were not detected in the monkeys vaccinated with a negative control DNA vaccine until day 6, which was 2 days after virus was first detected in the DNA vaccine groups.

To determine if infectious virus was present in the blood of challenged monkeys, we performed plaque assays on whole blood. No infectious viruses were detected in the blood from monkeys that were vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine, L1R DNA vaccine, or Dryvax (data not shown). In contrast, infectious viruses were detected in the blood of all three monkeys vaccinated with the negative control DNA vaccine (Fig. 4b).

Because virions could be present in the blood but not detected by plaque assay due to the presence of inhibitors (e.g., neutralizing antibodies and/or complement), we assayed for the presence of MPOV genomes in the blood using real-time PCR. Viral genomes were detected in the blood of all monkeys vaccinated with the negative control DNA vaccine. In the monkey that developed hemorrhagic monkeypox (CH28), viral genomes were detected as early as day 2 and continued to rise, apparently unchecked, until death on day 7. Viral genomes were detected in two monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine and both monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine. In these four monkeys, levels of infectious virus in oral secretions peaked before viral genomes were detected in the blood. The same three monkeys that had no infectious virus detected in oral secretions (CH93 vaccinated with 4pox DNA vaccine and CH39 and CH65 vaccinated with Dryvax) also had no MPOV genomes detected in their blood (Fig. 4c).

Monkeys vaccinated with DNA vaccines that survived challenge but still shed virus (L201-1, RC114, CH63, and CH74) had detectable levels of infectious viruses in throat swabs at least 2 days before viral genomes were detected in the blood (Fig. 4a and c). Moreover, these monkeys had infectious viruses in their throats 2 days before infectious virus was detected in the throat swabs of the negative control monkeys. One possible explanation for the early presence of virus in the throat swabs of partially protected animals is the detection of input challenge virions that remained infectious after being opsonized by effector cells and cleared through the lungs. In animals that were better protected (CH93, CH65, and CH39), we speculate that the immune response was capable of inactivating the input virus by redundant mechanisms, which effectively eliminated all forms of infectious virus. In the negative control monkeys, infectious virus was not detected in oral secretions until the time that the rash appeared, day 6, suggesting that the virus could have been shed from lesions in the oral and pharyngeal mucous membranes.

Antibody responses before and after challenge.

PRNT revealed that all of the monkeys except CH28 responded to the MPOV challenge by producing neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 5a). CH28 developed rapidly progressing hemorrhagic monkeypox and died on day 7, before detectable levels of antibodies were produced. Although the other two negative control monkeys produced antibodies capable of neutralizing >80% of the virus, the response was not detectable until 10 days after challenge, and the titers never exceeded 40. The rise in neutralizing antibody indicated that all of the monkeys in this study, including those completely protected from clinical disease, responded immunologically to the challenge virus.

FIG. 5.

Antibody responses before and after MPOV challenge. (a) Sera from monkeys vaccinated with 4pox DNA vaccine, L1R DNA vaccine, negative control (Neg. cont.) DNA vaccine, or Dryvax were collected 1 week before MPOV challenge, at the time of challenge (day 0), and at the indicated times after challenge. PRNT 80% neutralization titers are shown. (b) Immunogen-specific antibody titers in sera collected during the week before challenge were determined by ELISA using partially purified A27L, L1R, B5R, or A33R protein expressed in E. coli. Each bar represents the geometric mean titer obtained from at least two experiments. (c) MPOV-specific neutralizing antibody titers in sera collected at the time of MPOV challenge (day 0). The bars represent the mean value of two to four determinations ± standard deviation.

To measure the immunogen-specific antibody responses, we prepared partially purified A27L, L1R, B5R, and A33R VACV antigens from E. coli and evaluated serum collected from the vaccinated monkeys by ELISA (Fig. 5b). Antibody responses to all four immunogens were detected in only one of the monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine (CH93). This monkey had only one lesion, no virus in oral secretions, and no viremia, making it the most completely protected monkey other than the Dryvax-vaccinated monkeys. The other two monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine were positive for A27L, B5R, and A33R but not L1R. Monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine had relatively high L1R-specific antibody responses and were negative for the other three antigens. The two monkeys vaccinated with Dryvax exhibited very different antigen-specific antibody responses. CH39 had levels of antibodies undetectable by ELISA, and CH65 had relatively strong antibody responses to all four antigens. These Dryvax-vaccinated monkeys had VACV-infected-cell lysate ELISA titers and PRNT titers within twofold of each other (Fig. 1a), indicating that the net VACV-specific antibody responses in these monkeys were similar. The fact that CH39 showed no clinical signs of disease after challenge indicates that high levels of antibodies to A27L, L1R, B5R, and A33R were not required for protection.

Previous work had demonstrated that after the initial vaccination series, representative monkeys vaccinated with 4pox DNA vaccine or L1R DNA vaccine had antibody responses capable of binding MPOV orthologous proteins and cross-neutralizing MPOV (13). To determine the levels of MPOV-neutralizing antibodies at the time of challenge, we performed MPOV PRNT with sera collected on the day of challenge (Fig. 5c). Low levels of MPOV-neutralizing antibodies were detected in all of the monkeys except those vaccinated with the negative control DNA vaccines. Monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine had higher levels of MPOV-neutralizing antibodies than those vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine and were better protected. It is possible that the higher levels of neutralizing antibodies in the monkeys vaccinated with the 4pox DNA vaccine were responsible for the greater levels of protection in the 4pox DNA vaccine group compared to the L1R DNA vaccine group. Alternatively, the greater level of protection could be due to immune responses to one or more of the other three immunogens in the 4pox DNA vaccine.

Summary.

Remarkably little is known about the mechanism by which vaccination with VACV confers protection against orthopoxviruses. Several lines of evidence, primarily natural experiments involving smallpox patients with underlying immune system defects, indicate that both the humoral and cell-mediated arms of the immune system play important roles in protection (19). Recently, Belyakov et al. reported that antibodies were necessary for protection against disease in vaccinated mice whereas CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were neither necessary nor sufficient (1). In that same study, the CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell responses were important in conferring protection against natural infection and were sufficient to protect against lethal disease in the absence of antibody (1). Here, we focused on four VACV immunogens that are known to be targets of neutralizing or otherwise protective antibody responses (7, 8, 11, 20, 25, 26, 30). We evaluated the humoral, but not cell-mediated, responses following vaccination. In future studies, we will investigate whether the antibody responses are sufficient to protect or if cell-mediated responses elicited by one or more of the immunogens contained in the DNA vaccine are necessary to achieve the observed protection.

Vaccination with a single VACV gene that encodes a known target of neutralizing antibodies, L1R, protected against lethality but not against severe disease. The clinical symptoms of the monkeys vaccinated with the L1R DNA vaccine were similar to those in the monkeys challenged with a fourfold-lower dose of virus (Fig. 2b). Thus, mitigation of disease could be due to reduction of the effective challenge dose by neutralization of the challenge virus. MPOV-neutralizing antibodies in the sera of monkeys vaccinated with L1R were detected at the time of challenge, but at very low levels. These sera had high levels of anti-L1R antibodies as measured by immunogen-specific ELISAs, indicating that the anti-L1R response elicited by the DNA vaccine might have contained a high proportion of nonneutralizing anti-L1R antibodies. These same sera had higher levels of VACV-neutralizing antibodies (data not shown), indicating that to protect against monkeypox, it might be beneficial to vaccinate with the MPOV L1R ortholog. Similarly, the use of L1R, A27L, A33R, and B5R orthologs homologous to the challenge virus, whether it is VACV, MPOV, or variola virus, might improve the efficacy of the vaccine.

We demonstrated here that a DNA vaccine comprised of four VACV genes and administered by gene gun is capable of protecting nonhuman primates against severe monkeypox. This is the first report demonstrating that a subunit vaccine is capable of protecting nonhuman primates from any poxvirus-associated disease. The DNA-vaccinated monkey with the highest prechallenge antibody responses, CH93, was almost completely protected (a single lesion, 1 day of fever, no virus detected in oral secretions, and no viremia). This finding leads us to believe that a subunit (gene- or protein-based) poxvirus vaccine has the potential to mimic the protection afforded by live VACV administered by scarification. Such a vaccine would contribute greatly to vaccination strategies aimed at reducing the health hazards of the present smallpox vaccine.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Geisbert for performing clinical chemistries, L. Hensley and R. Fisher for help in blood sample processing, K. Stabler for technical assistance, M. S. Ibrahim for providing the optimized assay for detecting the MPOV genome, and P. Rico for serving as attending veterinarian. We also thank J. Huggins for providing us with MPOV-Z79, as well as helpful discussions regarding monkeypox disease in nonhuman primates. The particle-mediated epidermal delivery device (gene gun) was kindly provided by Powderject Vaccines Inc., Madison, Wis.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

The research described here was sponsored by the Military Biological Defense Research Program, U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command, project no. 02-4-7I-095.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belyakov, I. M., P. Earl, A. Dzutsev, V. A. Kuznetsov, M. Lemon, L. S. Wyatt, J. T. Snyder, J. D. Ahlers, G. Franchini, B. Moss, and J. A. Berzofsky. 2003. Shared modes of protection against poxvirus infection by attenuated and conventional smallpox vaccine viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9458-9463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:537-540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Supplemental recommendations of adverse events following smallpox vaccine in the pre-event vaccination program: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:282-284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Update: adverse events following civilian smallpox vaccination—United States, 2003. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:419-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52:642-646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Vaccinia (smallpox) vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 50(RR-10). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czerny, C. P., and H. Mahnel. 1990. Structural and functional analysis of orthopoxvirus epitopes with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2341-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czerny, C. P., S. Johann, L. Holzle, and H. Meyer. 1994. Epitope detection in the envelope of intracellular naked orthopox viruses and identification of encoding genes. Virology 200:764-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalgaard, J. B. 1957. Fatal myocarditis following smallpox vaccination. Am. Heart J. 54:156-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenner, F., D. A. Henderson, I. Arita, Z. Jezek, and I. D. Ladnyi. 1988. Smallpox and its eradication, p. 1-68. World Heath Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 10a.Fenner, F., D. A. Henderson, I. Arita, Z. Jezek, and I. D. Ladnyi. 1988. Smallpox and its eradication, p. 122-167. World Heath Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 11.Galmiche, M. C., J. Goenaga, R. Wittek, and L. Rindisbacher. 1999. Neutralizing and protective antibodies directed against vaccinia virus envelope antigens. Virology 254:71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammarlund, E., M. W. Lewis, S. G. Hansen, L. I. Strelow, J. A. Nelson, G. J. Sexton, J. M. Hanifin, and M. K. Slifka. 2003. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat. Med. 9:1131-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooper, J. W., D. M. Custer, and E. Thompson. 2003. Four-gene-combination DNA vaccine protects mice against a lethal vaccinia virus challenge and elicits appropriate antibody responses in nonhuman primates. Virology 306:181-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper, J. W., D. M. Custer, C. S. Schmaljohn, and A. L. Schmaljohn. 2000. DNA vaccination with vaccinia virus L1R and A33R genes protects mice against a lethal poxvirus challenge. Virology 266:329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper, J. W., D. M. Custer, E. Thompson, and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. DNA vaccination with the Hantaan virus M gene protects hamsters against three of four HFRS hantaviruses and elicits a high-titer neutralizing antibody response in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 75:8469-8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutin, Y., R. J. Williams, P. Malfait, R. Pebody, V. N. Loparev, S. L. Ropp, M. Rodriguez, J. C. Knight, F. K. Tshioko, A. S. Khan, M. V. Szczeniowski, and J. J. Esposito. 2001. Outbreak of human monkeypox, Democratic Republic of Congo, 1996 to 1997. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:434-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim, M. S., D. A. Kulesh, S. S. Saleh, I. K. Damon, J. J. Esposito, A. L. Schmaljohn, and P. B. Jahrling. 2003. Real-time PCR assay to detect smallpox virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3835-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jezek, Z., and F. Fenner. 1988. Clinical features of human monkeypox, p. 58-80. In J. L. Melnick (ed.), Monographs in virology, vol. 17. Karger, Basel, Switzerland.

- 18a.Jezek, Z., and F. Fenner. 1988. Epidemiology of human monkeypox, p. 81-109. In J. L. Melnick (ed.), Monographs in virology, vol. 17. Karger, Basel, Switzerland.

- 19.Kempe, C. H. 1960. Studies on smallpox and complications of smallpox vaccination. Pediatrics 25:176-189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law, M., and G. L. Smith. 2001. Antibody neutralization of the extracellular enveloped form of vaccinia virus. Virology 280:132-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClain, D. J., S. Harrison, C. L. Yeager, J. Cruz, F. A. Ennis, P. Gibbs, M. S. Wright, P. L. Summers, J. D. Arthur, and J. A. Graham. 1997. Immunologic responses to vaccinia vaccines administered by different parenteral routes. J. Infect. Dis. 175:756-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McConnell, S., Y. F. Herman, D. E. Mattson, D. L. Huxsoll, C. M. Lang, and R. H. Yager. 1964. Protection of rhesus monkeys against monkeypox by vaccinia virus immunization. Am. J. Vet. Res. 25:192-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss, B. 2001. Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication, 2866-2868. In D. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 23a.National Research Council. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

- 24.Prier, J. E., and R. M. Sauer. 1960. A pox disease of monkeys. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 85:951-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez, J. C., E. Tapia, and M. Esteban. 2002. Administration to mice of a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes the intracellular mature virus form of vaccinia virus limits virus replication efficiently under prophylactic and therapeutic conditions. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1059-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez, J. F., and M. Esteban. 1987. Mapping and nucleotide sequence of the vaccinia virus gene that encodes a 14-kilodalton fusion protein. J. Virol. 61:3550-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenthal, S. R., M. Merchlinsky, C. Kleppinger, and K. L. Goldenthal. 2001. Developing new smallpox vaccines. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:920-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shchelkunov, S. N., A. V. Totmenin, P. F. Safronov, M. V. Mikheev, V. V. Gutorov, O. I. Ryazankina, N. A. Petrov, I. V. Babkin, E. A. Uvarova, L. S. Sandakhchiev, J. R. Sisler, J. J. Esposito, I. K. Damon, P. B. Jahrling, and B. Moss. 2002. Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology 297:172-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weltzin, R., J. Liu, K. V. Pugachev, G. A. Myers, B. Coughlin, P. S. Blum, R. Nichols, C. Johnson, J. Cruz, J. S. Kennedy, F. A. Ennis, and T. P. Monath. 2003. Clonal vaccinia virus grown in cell culture as a new smallpox vaccine. Nat. Med. 9:1125-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolffe, E. J., S. Vijaya, and B. Moss. 1995. A myristylated membrane protein encoded by the vaccinia virus L1R open reading frame is the target of potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Virology 211:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]