Abstract

The retrovirus type B leukemogenic virus (TBLV) causes T-cell lymphomas in mice. We have identified the Rorγ locus as an integration site in 19% of TBLV-induced tumors. Overexpression of one or more Rorγ isoforms in >77% of the tumors tested may complement apoptotic effects of c-myc overexpression.

Type B leukemogenic virus (TBLV) is a retrovirus that is more than 98% identical to mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) (1, 7). Differences between MMTV and TBLV include a 440-bp deletion of U3 sequences present within the MMTV long terminal repeat (LTR). This deletion removes negative regulatory elements that inhibit viral transcription in many cell types, including lymphoid cells. LTR sequences flanking the deletion also are triplicated in the TBLV U3 region to form a T-cell-specific enhancer (24). Our previous results have shown that cis-acting sequences from the TBLV LTR are sufficient to convert the disease tropism of an infectious MMTV provirus from relatively long latency mammary tumors (6 to 9 months) to rapidly appearing T-cell lymphomas (2 to 3 months) (2).

Retroviruses that lack encoded oncogenes appear to induce cancer by insertional mutagenesis, leading to deregulation of nearby genes. Because retroviral integration is relatively random, identification of viral insertions within or near the same genes in different tumors suggests that there has been selection for outgrowth of cells carrying specific insertions. Such common integration sites (CISs) have been used as molecular tags to identify oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and oncogenic pathways (5, 12, 17, 19, 25, 31). There are at least nine MMTV CISs, which generally fall into three categories (Wnt, Fgf, and Notch family genes [4, 16, 20, 21, 33]), whereas only two CISs, Tblvi1 and c-myc, have been described for TBLV. The Tblvi1 CIS was identified in 20% of 55 TBLV-induced T-cell lymphomas examined (26) and mapped to the mouse X chromosome, but the target gene(s) remains unknown. We have detected integrations within or near the c-myc locus in 23% of TBLV-induced tumors (references 3 and 28 and data not shown). However, unlike many other murine retroviral studies, our previous analysis of 35 TBLV-induced tumors revealed only two tumors with detectable c-myc arrangement by Southern analysis, while PCR analysis confirmed that those two tumors plus nine others had TBLV integrations near or within this locus (3). Surprisingly, one tumor (T623B) had at least seven TBLV insertions at four sites within or near the c-myc locus. These studies suggested that TBLV-induced lymphomas are polyclonal and that many of the integrations could not be detected by Southern blotting due to the presence of multiple tumor cell clones.

Rorγ is a common TBLV integration site.

Using PCR analysis, we identified proviral insertions within the Rorγ (Rorc) locus, which encodes at least two protein isoforms. Rorγ and its thymus-specific isoform, Rorγt, are members of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that includes ligand-regulated transcription factors and receptors for which a specific ligand has not been identified (29). Rorγ also is known as RORC, RZR, thymus orphan receptor, and nuclear receptor 1F3 (22, 23, 27). Rorγ and Rorγt are highly related proteins that use distinct promoters and differ only at their amino termini (11, 13, 34). Rorγ-knockout mice, which lose expression of both RNA isoforms, lack lymph nodes and Peyer's patches, demonstrating a requirement for Rorγ/γt in lymphoid organogenesis (10, 14, 30). These mice also show a 75% reduction of total T cells and greatly reduced expression of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-XL (14, 30). Exogenous expression of either isoform in T-cell hybridomas inhibited interleukin-2 and Fas ligand expression and blocked T-cell receptor-induced cell proliferation and apoptosis (11, 18). Rorγ-null mice also have an increased rate of apoptosis and proliferation, resulting in rapid T-cell lymphoma formation (32). A recent report of Rorγt-deficient mice has ascribed most of the gross anomalies to the thymus-specific form (9).

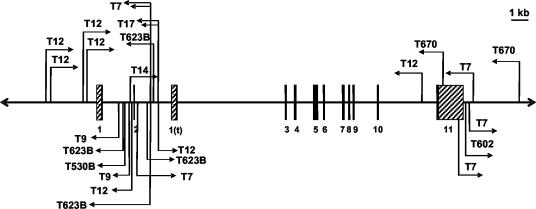

In this study we screened a panel of 47 TBLV-induced tumors by PCR analysis using 26 primer pairs consisting of a forward or reverse TBLV-LTR primer and a Rorγ genomic primer (combinations of those given in Table 1) as previously described (3). We detected TBLV integrations within or near the Rorγ locus for 9 of the 47 tumors tested (19%) (Fig. 1). Several of these tumors (T7, T9, T12, T623B, and T670) contained multiple TBLV integrations in the same tumor but in different locations. Insertions occurred near the beginning or end of the gene, consistent with an enhancer insertion mechanism. No integrations interrupting the coding regions were detected since the two integrations in exon 11, T670 and T7, are located in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). The most common clustering of integrations occurred within intron 2 of Rorγ, with six TBLV insertions detected in five different tumors. TBLV integrations also were clustered near the 3′ end of the Rorγ locus, which may alter promoter activity (36) or transcript stability (insertions in the 3′ UTR). None of the integrations localized to the Rorγ locus by PCR could be detected by Southern analysis with either a 4.3-kb genomic probe spanning Rorγ exons 1 and 2, intron 1, and part of intron 2 through Rorγt exon 1(t) or a 3.9-kb probe including the 3′ UTR of Rorγ/γt exon 11 and downstream region, suggesting that only a portion of the tumor population contained the TBLV integration. The majority of the TBLV-induced tumors appeared to be at least semiclonal as judged by Southern blotting with T-cell receptor β and γ probes (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Primers used to identify TBLV integrations within the Rorγ/γt locus

| Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Location-orientationa |

|---|---|---|

| TBLV-LTR408(+) | CCAATAAGACCAATCCAATAGGTAGAC | TBLV-LTR U3, forward |

| TBLV-LTR408(+)long | TTTACCAATAAGACCAATCCAATAGGTAGAC | TBLV-LTR U3, forward |

| TBLV-LTR786(−) | CACTCAGAGCTCAGATCAGAAC | TBLV-LTR U3, reverse |

| TBLV-LTR786(−)long | AAAATAGAACACTCAGAGCTCAGATCAGAAC | TBLV-LTR U3, reverse |

| RORCex1(−) | GTGCCGTCCTTGCTGCCC | Exon 1, reverse |

| RORCex3(+) | GATTCGTGGGGACAAGTCATC | Exon 3, forward |

| RORCt170(−) | CTCATGACTGAGAACTTGGCTC | Exon 1(t), reverse |

| RORC281(+) | CAGTTCAGGAGGCATGAGTGAA | Exon 2, forward |

| RORC(−)5 | TCCTTCCTCCAGATCACTTTGACAGCCC | Exon 11, reverse |

| RORCintron10(−) | TAGGAGGGAATGAGTACTTCG | Intron 10, reverse |

| RORC(−) | GAGGTGTGGGTCTTCTTTGCAGC | Exon 2, reverse |

| RORC488(+) | CAGCAGCAAGTGATGGAG | Exon 11, forward |

| RORCex/in8(−) | TCACCCAAGGCTCGAAACAGC | Exon 8, reverse |

| T670-646(−) | GCCTAGGATACATGCTTGCC | 3′ of exon 11, forward |

| T670-616(−) | GTGTCAGATTCGTTAGCAGTC | Exon 11, forward |

| RORCt(+) | ACCTCCACTGCCAGCTGTGTGCTGTC | Intron 2 [exon 1(t)], forward |

| RORCex4(−) | CACATTACACTGCTGGCTGC | Exon 4, reverse |

Primer location in either the TBLV-LTR or Rorγ/γt locus; orientation relative to provirus or gene coding sequence.

FIG. 1.

Location of TBLV insertions within the Rorγ locus in T-cell lymphomas as detected by PCR. Black arrows represent the location and orientation of TBLV proviruses. The tumors (designated T) containing the integrations are indicated closest to the arrow. Black bars represent Rorγ exons; 5′ and 3′ UTRs are indicated by hatched boxes.

The average size of the PCR products obtained (ca. 5 kb) may limit detection of all integrations within the Rorγ locus. We attempted to overcome such limitations by using sufficient primer sets to completely scan the locus (Table 1). Nevertheless, 5 kb represents the approximate region screened on either end of the gene, whereas retroviral insertions have been shown to affect gene expression at distances over 200 kb (15). Furthermore, Rorγ locus intronic sequences include many single nucleotide runs and Alu repeats, which may have further diminished PCR product detection.

The Rorγ locus was recently identified as a Moloney murine leukemia virus (MuLV) CIS in studies identifying p27Kip1 collaborating oncogenes (12). Complementarity between these two genes was suggested by Winoto and Littman (35) and indicates the utility of using numerous genetic and viral models to examine oncogenic pathways since other large-scale retroviral tagging studies using MuLV failed to detect the Rorγ locus as a CIS (19, 25). Furthermore, 8.5% of the TBLV-induced tumors showed integrations in both c-myc and Rorγ (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

TBLV tumors with integrations at multiple loci

| Tumor | No. of integrations at locus:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| c-myc | Rorγ/γt | |

| T9 | 1 | 2 |

| T17 | 1 | 2 |

| T602 | 1 | 1 |

| T623B | 7 | 4 |

Rorγ/γt expression in developing thymocytes is tightly controlled and is necessary for T-cell maturation (10, 13). Two recent studies using retroviral tagging identified the locus Sox4, encoding a transcription factor involved in B- and T-cell development, as a CIS for Moloney MuLV (25, 31). Although Sox4 was the most frequently targeted CIS in the study by Suzuki et al. (31) (55 of 194 tumors), we were unable to detect any TBLV integrations near Sox4. As previously suggested (8), these studies indicate that the unique TBLV enhancer is likely to identify additional cellular genes that are not identified by MuLV insertional mutagenesis.

Rorγ and Rorγt are overexpressed in TBLV-induced tumors.

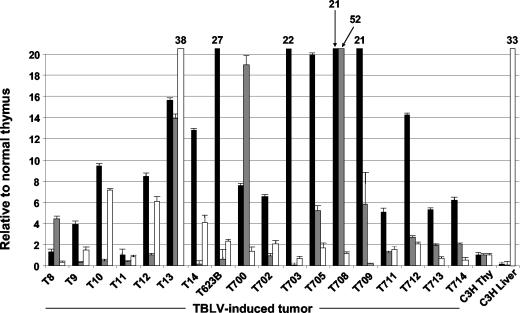

Rorγ, Rorγt, c-myc and Gapdh mRNA levels in the TBLV-induced lymphomas were analyzed and compared to those from normal thymus (Fig. 2). Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed using an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detection system and SYBR Green Universal Master Mix according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). (Primers are shown in Table 3.) Rorγ levels varied from 0.2- to 38-fold that observed in normal thymus, and 7 of the 18 tumors tested (∼39%) showed at least twofold overexpression (and significant differences at the 95% confidence level by Student t tests). In contrast to previous reports (11), we routinely detected little or no Rorγ expression in the thymus, yet expression was abundant in the liver (33-fold higher than that of normal thymus). TBLV integrations were identified in two of the tumors showing Rorγ overexpression (T12 and T14). Seven different integration sites were detected in T12, four upstream of Rorγ exon 1 and one in intron 2 in the same transcriptional orientation, and one each within introns 1 and 10, both in the reverse orientation. Rorγt expression levels in the tumors tested ranged from 0.2- to 52-fold that detected in normal thymus. Nine of the 18 lymphomas tested (∼50%) showed at least twofold Rorγt overexpression, which was significantly different from levels in normal thymus; together, more than 77% of the TBLV-induced tumors overexpressed one or more Rorγ isoforms. We have not yet detected TBLV integrations near the Rorγ locus in any of the tumors showing Rorγt overexpression. However, proviral insertions may occur at more distal locations than those that were examined in this study, or Rorγt may be indirectly activated.

FIG. 2.

Both c-myc and Rorγ/γt are overexpressed in the majority of TBLV-induced tumors. c-myc (black bars), Rorγt (gray bars), and Rorγ (white bars) expression levels from real-time RT-PCR analysis are shown relative to that from normal thymus. The standard errors for gene expression levels greater than 20-fold that of normal thymus are as follows: T13, Rorγ, 38 ± 0.4; T623B, c-myc, 27 ± 0.1; T703, c-myc, 22 ± 0.1; T708, c-myc, 21 ± 0.4; T708, Rorγt, 52 ± 0.2; T709, c-myc, 21 ± 0.3; C3H liver, Rorγ, 33 ± 0.02. Gene expression experiments were performed in triplicate three to five times depending on the availability of tumor RNA. Real-time RT-PCR primers were used at a final concentration of 0.1 to 0.2 μM and had been previously determined to have similar amplification efficiencies (slopes of <0.1).

TABLE 3.

Primers used for real-time RT-PCR analysis

| Primer name | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| RORC(−) | GAGGTGTGGGTCTTCTTTGCAGC |

| RORC(+)6 | GGAGGGCAGCAAGGACGGCAC |

| RORCt170(−) | CTCATGACTGAGAACTTGGCTC |

| RORCt(+) | ACCTCCACTGCCAGCTGTGTGCTGTC |

| c-myc568(+) | TTCTGACAGAACTGATGCGCT |

| c-myc695(+) | TATGGCTGAAGCTTACAGTCC |

| gapdh197(+) | CACGGCAAATTCAACGGCA |

| gapdh247(−) | GATGACAAGCTTCCCATTCTCG |

Consistent with our previous analysis (28), c-myc overexpression was observed in 89% (16 of 18) of the TBLV-induced tumors tested. TBLV integrations have been detected in four of the primary tumors (T9, T10, T623B, and T700) with c-myc overexpression (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Elevated c-myc RNA levels also were detected in T16 and T17 cells passaged in syngeneic mice. Unfortunately, primary tumor RNA was available from only two of the four tumors that contain TBLV insertions at both c-myc and Rorγ loci. Of these two tumors, T9 showed ca. fourfold c-myc overexpression and did not show Rorγ or Rorγt overexpression; T623B showed high levels of c-myc overexpression (27-fold) and seven detected integrations and modest (ca. twofold) Rorγ overexpression (with four detected integrations). We have previously demonstrated that the proviral location and orientation relative to c-myc and the composition of the enhancer within the TBLV LTR all affect target gene expression (3).

The observations that many tumors overexpressed both c-myc and Rorγ/γt and that ∼9% of tumors had detectable insertions in both genes suggest that these transcription factors are important individually in the progression toward disease and may collaborate during T-cell lymphomagenesis. The idea that the antiapoptotic factors Rorγ and Rorγt (14, 30, 32) may antagonize the known proapoptotic effects of c-Myc (6) is being explored.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Dudley lab, particularly Jenny Mertz, for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by NIH grant P01 77760.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball, J. K., L. O. Arthur, and G. A. Dekaban. 1985. The involvement of a type-B retrovirus in the induction of thymic lymphomas. Virology 140:159-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, J. K., and G. A. Dekaban. 1987. Characterization of early molecular biological events associated with thymic lymphoma induction following infection with a thymotropic type-B retrovirus. Virology 161:357-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broussard, D. R., J. A. Mertz, M. Lozano, and J. P. Dudley. 2002. Selection for c-myc integration sites in polyclonal T-cell lymphomas. J. Virol. 76:2087-2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan, R., and G. H. Smith. 2000. MMTV-induced mammary tumorigenesis: gene discovery, progression to malignancy and cellular pathways. Oncogene 19:992-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee, G., A. Rosner, Y. Han, E. T. Zelazny, B. Li, R. D. Cardiff, and A. S. Perkins. 2002. Acceleration of mouse mammary tumor virus-induced murine mammary tumorigenesis by a p53 172H transgene: influence of FVB background on tumor latency and identification of novel sites of proviral insertion. Am. J. Pathol. 161:2241-2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang, C. V. 1999. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dekaban, G. A., and J. K. Ball. 1984. Integration of type B retroviral DNA in virus-induced primary murine thymic lymphomas. J. Virol. 52:784-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudley, J. P. 2003. Tag, you're hit: retroviral insertions identify genes involved in cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 9:43-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberl, G., and D. R. Littman. 2003. The role of the nuclear hormone receptor RORγt in the development of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches. Immunol. Rev. 195:81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, Y. W., C. Beers, M. L. Deftos, E. W. Ojala, K. A. Forbush, and M. J. Bevan. 2000. Down-regulation of the orphan nuclear receptor RORγt is essential for T lymphocyte maturation. J. Immunol. 164:5668-5674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, Y. W., M. L. Deftos, E. W. Ojala, and M. J. Bevan. 1998. RORγt, a novel isoform of an orphan receptor, negatively regulates Fas ligand expression and IL-2 production in T cells. Immunity 9:797-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang, H. C., C. P. Martins, Y. Bronkhorst, E. Randel, A. Berns, M. Fero, and B. E. Clurman. 2002. Identification of oncogenes collaborating with p27Kip1 loss by insertional mutagenesis and high-throughput insertion site analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11293-11298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jetten, A. M., S. Kurebayashi, and E. Ueda. 2001. The ROR nuclear orphan receptor subfamily: critical regulators of multiple biological processes. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 69:205-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurebayashi, S., E. Ueda, M. Sakaue, D. D. Patel, A. Medvedev, F. Zhang, and A. M. Jetten. 2000. Retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma (RORγ) is essential for lymphoid organogenesis and controls apoptosis during thymopoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10132-10137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazo, P. A., J. S. Lee, and P. N. Tsichlis. 1990. Long-distance activation of the Myc protooncogene by provirus insertion in Mlvi-1 or Mlvi-4 in rat T-cell lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:170-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, F. S., T. F. Lane, A. Kuo, G. M. Shackleford, and P. Leder. 1995. Insertional mutagenesis identifies a member of the Wnt gene family as a candidate oncogene in the mammary epithelium of int-2/Fgf-3 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:2268-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li, J., H. Shen, K. L. Himmel, A. J. Dupuy, D. A. Largaespada, T. Nakamura, J. D. Shaughnessy, Jr., N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 1999. Leukaemia disease genes: large-scale cloning and pathway predictions. Nat. Genet. 23:348-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Littman, D. R., Z. Sun, D. Unutmaz, M. J. Sunshine, H. T. Petrie, and Y. R. Zou. 1999. Role of the nuclear hormone receptor RORγ in transcriptional regulation, thymocyte survival, and lymphoid organogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 64:373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund, A. H., G. Turner, A. Trubetskoy, E. Verhoeven, E. Wientjens, D. Hulsman, R. Russell, R. A. DePinho, J. Lenz, and M. van Lohuizen. 2002. Genome-wide retroviral insertional tagging of genes involved in cancer in Cdkn2a-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 32:160-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacArthur, C. A., D. B. Shankar, and G. M. Shackleford. 1995. Fgf-8, activated by proviral insertion, cooperates with the Wnt-1 transgene in murine mammary tumorigenesis. J. Virol. 69:2501-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchetti, A., F. Buttitta, S. Miyazaki, D. Gallahan, G. H. Smith, and R. Callahan. 1995. Int-6, a highly conserved, widely expressed gene, is mutated by mouse mammary tumor virus in mammary preneoplasia. J. Virol. 69:1932-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medvedev, A., A. Chistokhina, T. Hirose, and A. M. Jetten. 1997. Genomic structure and chromosomal mapping of the nuclear orphan receptor RORγ (RORC) gene. Genomics 46:93-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medvedev, A., Z. H. Yan, T. Hirose, V. Giguere, and A. M. Jetten. 1996. Cloning of a cDNA encoding the murine orphan receptor RZR/RORγ and characterization of its response element. Gene 181:199-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mertz, J. A., F. Mustafa, S. Meyers, and J. P. Dudley. 2001. Type B leukemogenic virus has a T-cell-specific enhancer that binds AML-1. J. Virol. 75:2174-2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mikkers, H., J. Allen, and A. Berns. 2002. Proviral activation of the tumor suppressor E2a contributes to T cell lymphomagenesis in EμMyc transgenic mice. Oncogene 21:6559-6566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller, R. E., L. Baggio, C. A. Kozak, and J. K. Ball. 1992. A common integration locus in type B retrovirus-induced thymic lymphomas. Virology 191:628-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortiz, M. A., F. J. Piedrafita, M. Pfahl, and R. Maki. 1995. TOR: a new orphan receptor expressed in the thymus that can modulate retinoid and thyroid hormone signals. Mol. Endocrinol. 9:1679-1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajan, L., D. Broussard, M. Lozano, C. G. Lee, C. A. Kozak, and J. P. Dudley. 2000. The c-myc locus is a common integration site in type B retrovirus-induced T-cell lymphomas. J. Virol. 74:2466-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stehlin-Gaon, C., D. Willmann, D. Zeyer, S. Sanglier, A. Van Dorsselaer, J. P. Renaud, D. Moras, and R. Schule. 2003. All-trans retinoic acid is a ligand for the orphan nuclear receptor RORβ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10:820-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun, Z., D. Unutmaz, Y. R. Zou, M. J. Sunshine, A. Pierani, S. Brenner-Morton, R. E. Mebius, and D. R. Littman. 2000. Requirement for RORγ in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science 288:2369-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki, T., H. Shen, K. Akagi, H. C. Morse, J. D. Malley, D. Q. Naiman, N. A. Jenkins, and N. G. Copeland. 2002. New genes involved in cancer identified by retroviral tagging. Nat. Genet. 32:166-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueda, E., S. Kurebayashi, M. Sakaue, M. Backlund, B. Koller, and A. M. Jetten. 2002. High incidence of T-cell lymphomas in mice deficient in the retinoid-related orphan receptor RORγ. Cancer Res. 62:901-909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Leeuwen, F., and R. Nusse. 1995. Oncogene activation and oncogene cooperation in MMTV-induced mouse mammary cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 6:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villey, I., R. de Chasseval, and J. P. de Villartay. 1999. RORγt, a thymus-specific isoform of the orphan nuclear receptor RORγ/TOR, is up-regulated by signaling through the pre-T cell receptor and binds to the TEA promoter. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:4072-4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winoto, A., and D. R. Littman. 2002. Nuclear hormone receptors in T lymphocytes. Cell 109(Suppl.):S57-S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeidler, R., S. Joos, H. J. Delecluse, G. Klobeck, M. Vuillaume, G. M. Lenoir, G. W. Bornkamm, and M. Lipp. 1994. Breakpoints of Burkitt's lymphoma t(8;22) translocations map within a distance of 300 kb downstream of MYC. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 9:282-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]