Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved mechanism that is essential for cell survival in starvation. Moreover, autophagy maintains cellular health by clearing unneeded or harmful materials from cells. Autophagy proceeds by the engulfment of bulk cytosol and organelles by a cup-shaped double membrane sheet known as the phagophore. The phagophore closes upon itself to form the autophagosome, which delivers its contents to the vacuole or lysosome for degradation. A multiprotein complex consisting of the protein kinase Atg1 together with Atg13, Atg17, Atg29, and Atg31 (ULK1, ATG13, FIP200, and ATG101 in humans) has a pivotal role in the earliest steps of this process. This review summarizes recent structural and ultrastructural analysis of the earliest step in autophagosome biogenesis and discusses a model in which the Atg1 complex clusters high curvature vesicles containing the integral membrane protein Atg9, thereby initiating the phagophore.

Keywords: SNAREs, Atg1, Atg9, Atg13, autophagy, ULK1, membrane bending, vesicle tethering

Autophagy and autophagy-related (Atg) proteins

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy), is a cellular self-degradative process in which cytosolic material is transported to the vacuole or lysosome for degradation. Autophagy evolved in unicellular organisms as a survival mechanism to provide free amino acids and other metabolic precursors during starvation [1]. Starvation is thus a potent inducer of autophagy. However, even under normal cellular conditions, autophagy is important for the clearance of damaged organelles and other toxic cytosolic materials. Autophagy is the major mechanism by which entire organelles are degraded. Thus, it is essential for cellular homeostasis in eukaryotes. Functional autophagy is linked to life span in many organisms, and its dysfunction to numerous degenerative diseases in humans including cancer, neurodegeneration and susceptibility to infections [2].

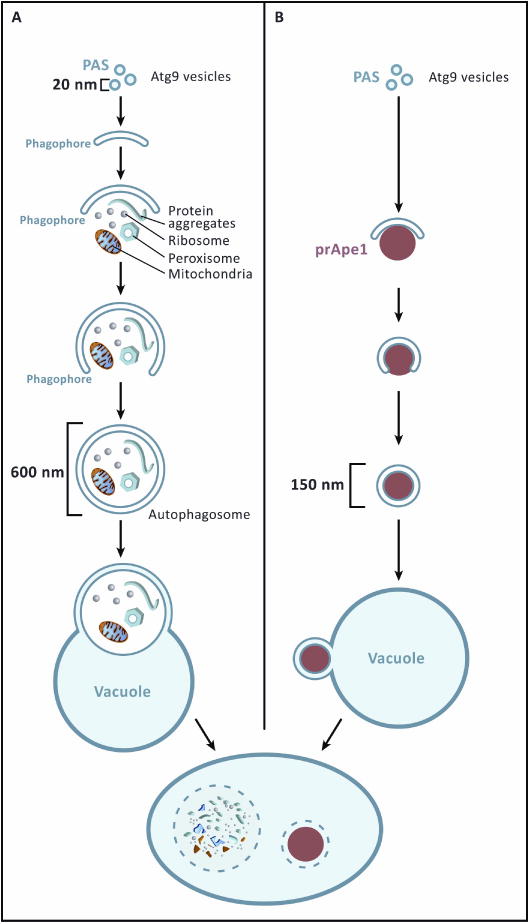

During autophagy, bulk cytosol, organelles, and inclusions are engulfed by a double-membraned vesicle termed the autophagosome. Autophagosomes in yeast can range in size from 300-900 nm (Fig. 1A). Once mature, the outer autophagosomal membrane fuses with the vacuolar or lysosomal membrane. The entire contents of the autophagosome including the inner membrane, are then degraded by lysosomal hydrolases. The resulting free amino acids and other metabolic precursors are then recycled back to the cytoplasm. The biogenesis of the autophagosome occurs de novo in the sense that autophagosomes are not formed by budding off another autophagosome [3, 4]. This raises the questions as to the origin of the autophagosomal membrane, its mechanism of initiation, and the determinants of its size and shape.

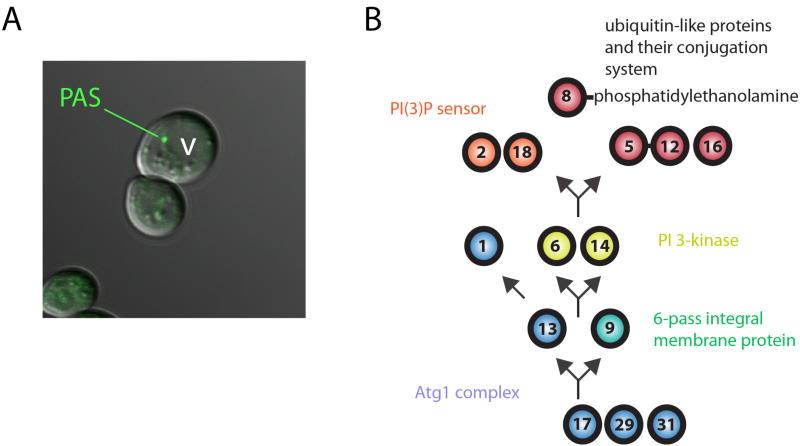

Figure 1.

Autophagy and the Cvt pathway in yeast. A. Starvation-induced bulk autophagy. Autophagosome biogenesis begins with a pool containing an estimated three Atg9-positive vesicles which may be as small as 20 nm in diameter. These vesicles fuse into a double-membrane sheet, which becomes the phagophore. The phagophore grows by addition of membrane and adopts the shape of a cup. The cup engulfs mitochondria, peroxisomes, ribosomes, inclusions, and bulk cytosol. The opening of the phagocytic cup eventually fuses and the structure is now the autophagosome, which in yeast is 300-900 nm in diameter. The autophagosome then fuses with the vacuole (lysosome in mammalian cells) such that the inner membrane and all of the contents are hydrolyzed. B. The Cvt pathway, a constitutive transport process in yeast with analogies to mammalian selective autophagy. The Cvt pathway begins with the fusion of Atg9 vesicles, as in (A). The main difference in this pathway is that the size and shape of the phagocytic cup are dictated by the size and shape of the substrate being engulfed, which is usually a single entity. Here a particle of the vacuolar peptidase precursor prApe1 is shown.

Autophagy can be both a selective and non-selective process. During non-selective autophagy, cytosolic components are engulfed by the autophagosome in an untargeted manner. Some of the autophagy machinery, however, is dedicated to the consumption of particular organelles, including mitochondria, lipid droplets, and peroxisomes, and this process is referred to as selective autophagy. In selective autophagy, the cargo being engulfed appears capable of templating the size of the autophagosome. For example in yeast, a constitutive selective autophagy pathway for cytosol to vacuole transport (Cvt) carries the protease Ape1 to its vacuolar site of action (Fig. 1B). In non-selective autophagy, the double membrane gains its shape and structure by mechanisms that remain mysterious. The autophagosomal membrane is initiated by the fusion of small vesicles to form a sheet (Fig. 1A). The membrane sheet continues to elongate to become a cup shaped structure called the phagophore (also known as the isolation membrane). Ultimately the phagophore folds back on itself, and the neck of the cup is sealed to form the closed autophagosome.

Most of what is known about autophagosome biogenesis comes from genetic studies in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae[5]. There are now 36 ATG (AuTophaGy-related) genes that have been discovered through S. cerevisiae genetics. The majority of these were subsequently found to be conserved and to have parallel functions in multicellular eukaryotes. It is therefore thought that most of the core mechanisms of autophagy are conserved from yeast to humans. The Atg proteins belong to six functional groups (Table 1). Among the Atg proteins, we will be primarily concerned with the Atg1 complex (ULK1 and ULK2 in humans), and the integral membrane protein Atg9, which are involved in the very earliest stages of autophagy. Recently, it has become clear that the Atg1 complex and Atg9 act in concert with various general-purpose membrane trafficking proteins including SNARE proteins, secretory proteins, Rabs and Rab GEFs, and tethering factors. Many of these proteins are better known for their roles in ER-to-Golgi trafficking and exocytosis, and lessons from these fields have helped to provide insights into the roles of these components in autophagy.

Table 1.

| Complex | Yeast | Human | Complex Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atg1/ULK1 complex | Atg1 | ULK1/2 | Atg1, which is a Ser/Thr kinase, forms an autophagy specific complex with Atg13, Atg17, Atg31 and Atg29. Atg17, Atg31, and Atg29 form a stable 2:2:2 complex regardless of cellular nutrient status and serve as a scaffold that is important for protein localization to the PAS. |

| Atg13 | ATG13 | ||

| Atg17 | FIP200 | ||

| Atg29 | |||

| Atg31 | |||

| ATG101 | |||

| Class III PI3K Complex | Vps34 | VPS34 | The Class III phosphatidylinositol 3 complex is responsible for the production of PI3P at the PAS. Atg14 specifically targets the complex to the PAS. |

| Vps15 | VPS15 | ||

| Vps30/Atg6 | Beclin 1 | ||

| Atg14 | ATG14L/BARKOR | ||

| Atg2-18 Complex | Atg2 | ATG2 | Atg18 is a PI3P sensor that forms a complex with Atg2 and Atg9. |

| Atg18 | WIPI1-4 | ||

| Atg12 Conjugation | Atg12 | ATG12 | Atg7 (EI like enzyme) and Atg10 (E2 like enzyme) conjugate |

| Atg7 | ATG7 | Atg12 to Atg5. Atg16 is a homodimer which forms a complex with Atg5 and Atg12 and is important for Atg8-PE conjugation. | |

| Atg10 | ATG10 | ||

| Atg5 | ATG5 | ||

| Atg16 | ATG16L1/2 | ||

| Atg8 Conjugation | Atg8 | LC3A/B/C GABARAP GABARAPL1/2/3 | Atg4 is a hydrolase which activates Atg8/LC3. Atg8 is conjugated to PE through Atg7 (E1 like enzyme), the Atg12-5-16 complex and Atg3 (E2 like enzyme). |

| Atg4 | ATG4A-D | ||

| Atg7 | ATG7 | ||

| Atg3 | ATG3 | ||

| Atg9 Associated | Atg9 | ATG9 | Integral membrane protein involved in autophagy. |

| Atg23 | Atg23 is a peripheral membrane protein required for Atg9 trafficking from the Golgi. | ||

| Atg27 | Atg27 is a type I integral membrane protein required for Atg9 trafficking from the Golgi. |

This review will focus on recent progress in our understanding of the initial stages of autophagosome formation, whereby an initial membrane source is provided, tethered and fused to form a double membrane sheet. We will focus primarily on bulk non selective autophagy in yeast but will highlight recent progress in the mammalian autophagy field. This review will also emphasize how Atg9 and the Atg1 kinase complex work together with other membrane trafficking proteins to initiate formation of the autophagosome.

Autophagosome formation begins at the PAS

In yeast, autophagy is initiated at a single diffraction-limited punctum as defined by light microscopy, referred to as the phagophore assembly site (PAS; also known as the preautophagosomal structure)[6] (Fig. 2A). The PAS is located near the vacuole and is the site of recruitment for all of the protein and membrane components required for autophagosome biogenesis. Yeast cells normally contain a single PAS, regardless of whether cells are exposed to nutrient rich or limiting conditions. Under nutrient rich conditions in yeast, the PAS serves as the point of initiation for Cvt vesicle biogenesis. Under starved conditions, non-selective autophagosome biogenesis in yeast commences at the PAS. Mammalian cells do not have a Cvt pathway and so lack a constitutive PAS. Autophagy in mammalian cells is analogous to that described in yeast in that both commence at a unique locus. Mammalian autophagy has been proposed on the basis of the most recent findings to commence either at the ER-mitochondrial junction [7] or the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) [8].

Figure 2.

The preautophagosomal structure. A. Fluorescence micrograph of the PAS. B. Schematic for the genetic hierarchy of Atg protein recruitment to the PAS.

The genetic hierarchy of Atg protein recruitment at the PAS in response to the upregulation of non-selective autophagy has been delineated [9](Fig. 2B). Three members of the Atg1 complex, Atg17, Atg29, and Atg31, are the most upstream components of non-selective autophagy and are constitutively recruited to the PAS under both nutrient rich and limiting conditions [9, 10]. Without these three proteins, and their selective autophagy counterpart Atg11, additional Atg proteins will not localize to the PAS. In mammalian cells, FIP200 is thought to be the functional counterpart of Atg11 and Atg17.

The human orthologs of Atg1 are ULK1-4, of which ULK1 is the most well-known. Only ULK1 and ULK2 have demonstrated roles in mammalian autophagy [11, 12]. ULK1 assembles into a complex with ATG13, FIP200, and ATG101 [13-17]. The C-terminal domain of ULK1 is capable of targeting membranes in cells [18], and as described below, is now referred to as the early autophagy targeting/tethering (EAT) domain. ATG13 is regulated by mTOR. ULK1 and ATG13 association appears to be constitutive. The phosphorylation status of ATG13 is most likely involved in regulating the conformation and activity of ULK1 within the context of the assembled complex [15]. Human FIP200 is a large predicted helical protein that is generally considered to be the functional counterpart of yeast Atg11 and Atg17, although it lacks statistically significant sequence homology to these proteins. There are no known human orthologs of Atg29 and Atg31, nor a yeast ortholog of ATG101. Overall, the similarities between the ULK1 and Atg1 complexes outnumber the differences, and are close enough that the core mechanisms described below seem likely to be conserved.

Initiation of phagophore formation

Biogenesis and transport of autophagic precursor vesicles

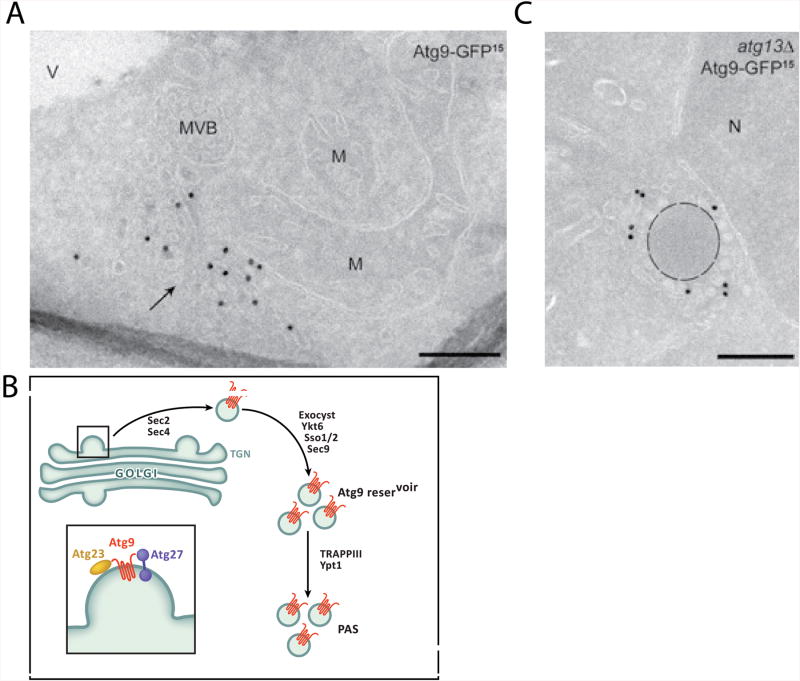

The sequential recruitment of autophagy factors and membranes results in the production of an elongated double membrane sheet. The sheet curves into a cup-shaped structure termed the phagophore. The formation of the phagophore is essential for autophagosome biogenesis and serves as the precursor to autophagosome formation. The initial membrane source required for phagophore formation in yeast is provided by 20-30 nm vesicles containing the integral membrane protein Atg9 [19]. Atg9 contains six transmembrane helices, which place both the N and C terminus in the cytosol. Prior to autophagy induction, Atg9 is found in a clustered cytosolic reservoir of 20-30 nm vesicles (Fig. 3A) [19]. The purpose of this reservoir appears to be to maintain a ready supply of Atg9 vesicles in a state that is inactive, but ready for rapid delivery to the PAS in the event of their need.

Figure 3.

Biogenesis and coalescence of Atg9 vesicles. A. Electron micrograph of Atg9 reservoir (arrow; reproduced by permission from [19]). B. Schematic of the trafficking of Atg9 vesicles from the TGN to the Atg9 reservoir, and onward to the PAS. Atg9 emerges from the TGN in tandem with Atg23 and Atg27, a peripheral and single-crossing integral membrane protein, respectively. Atg9 vesicles emerging from the TGN are sorted to a cytosolic reservoir near the mitochondrion in a process depending on the Rab/RabGEF pair Sec2 and Sec4, the SNAREs Ykt6, Sso1/2, and Sec9, and the exocyst complex. Once at the reservoir, the Atg9 vesicles acquire another Rab protein, Ypt1, and its multimeric GEF, the TRAPPIII complex. C. Coalescence of Atg9 vesicles is highlighted most dramatically adjoining a preApe1 particle in atg13Δ cells (reproduced by permission from [19]). V, vacuole, M, mitochondrion, MVB, multivesicular body. Scale bars are 200 nm.

Atg9 vesicles are generated in yeast through Golgi-related secretory and endosomal pathways [19-21]. In human cells in nutrient rich media, ATG9 exists within the Trans Golgi Network (TGN), recycling endosomes, early endosomes and late endosomes [22, 23]. Further details of Atg9 sorting have primarily been elucidated in yeast. Yeast Atg23 and Atg27, a peripheral and type I integral membrane protein, respectively, are essential for the trafficking of Atg9 vesicles from the Golgi to their reservoir [24-26] (Fig. 3B). These Atg9-containg vesicles do not contain typical endoplasmic reticulum (ER), TGN, or endosomal markers [19] suggesting that Atg9 vesicles are produced from the TGN in a manner dependent on Atg23 and Atg27 but divergent from the main secretory and endosomal pathways exiting the TGN.

Once formed, the transport of Atg9-containing vesicles away from the Golgi in yeast requires the post-Golgi secretory proteins Sec2 and Sec4 [27]. Sec4 is a Rab GTPase known for its role in exocytic vesicle delivery to the plasma membrane, while Sec2 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Sec4 [28]. Sec4 binds directly to the octameric exocyst complex, which targets secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane for exocytosis. Sec2, Sec4 and the exocyst complex have all been implicated in autophagy, and their role in autophagy, driving the transport of Atg9 vesicles, may be analogous to their role in exocytosis [29].

Vesicle clustering at the PAS

Atg9 recruitment is one of the earliest events at the PAS, occurring immediately downstream of Atg17. At the PAS, Atg9 resides in a cluster of ∼20-30 nm vesicles and tubes [19]. Each vesicle is estimated to contain ∼27 copies of Atg9 [21]. Yeast cells typically contain 1-3 separate Atg9 pools and upon autophagy induction, a single pool of Atg9 vesicles is translocated to the PAS [21]. In wild-type cells, the vesicles at the PAS under starvation conditions are hard to differentiate by electron microscopy (EM) from the Atg9 reservoir described above. However, in atg1Δ and atg13Δ cells, visually striking clusters of unfused Atg9 vesicles are formed surrounding the Cvt cargo, prApe1 particles (Fig. 3C) [19]. These observations suggest that the phagophore emerges by the coalescence of small Atg9 containing vesicles, and that clustering and fusion occur as separate steps. It has been estimated that three Atg9 vesicles are required to assemble at the PAS and fuse to initiate one autophagosome [21]. Recent work has identified that the most upstream autophagy regulatory complex, the Atg1 complex, is capable of tethering 20-30 nm vesicles in vitro [30], suggesting that it is the most likely candidate for an Atg9 vesicle tethering factor.

Regulation of vesicle clustering and Atg1 complex assembly

ATG1 was the first autophagy-related gene to be discovered. It is an amusing coincidence that the multiprotein complex containing Atg1 is also the first to arrive at the PAS. Atg1 consists of an N-terminal Ser/Thr kinase domain connected by a flexible linker to a C-terminal Early Autophagy Targeting/Tethering (EAT) domain [18, 30]. The Atg1 kinase complex is inactivated under normal cellular conditions through phosphorylation of both Atg1 and Atg13 by Tor [31, 32] and PKA[33]. Upon starvation, Atg13 becomes dephosphorylated and binds directly to the EAT domain of Atg1 and to Atg17. It thus acts as a bridge between Atg1 and Atg17, triggering the assembly of the subunits into a dimer of pentamers. Atg17 is in a constitutive complex with the small proteins Atg29 and Atg31. The Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 complex forms an extended double crescent shaped dimer and dimerization of the complex through the C-terminal α-helix of Atg17 is essential for autophagy activity in yeast [30]. The full Atg1 complex thus exists as a dimer of Atg1-Atg13-Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 pentamers [30]. Mutation of the eight identified Atg13 phosphorylation sites to Ala induces Atg1 complex formation in the absence of autophagy induction [34]. Moreover, a trimmed Atg1 complex pentamer can be reconstituted from dephosphorylated subunits expressed in E. coli[30]. Recently, a constitutive interaction between Atg1 and Atg13 was observed [35] suggesting that the Atg1 complex is regulated primarily at the level of its activity rather than its assembly. While it is no longer clear whether the binding of yeast Atg1 and Atg13 to one another is phosphoregulated, available evidence suggests that the Atg13-Atg17 interaction and thus the subsequent localization of Atg1 and Atg13 to the PAS is dependent on nutrient status.

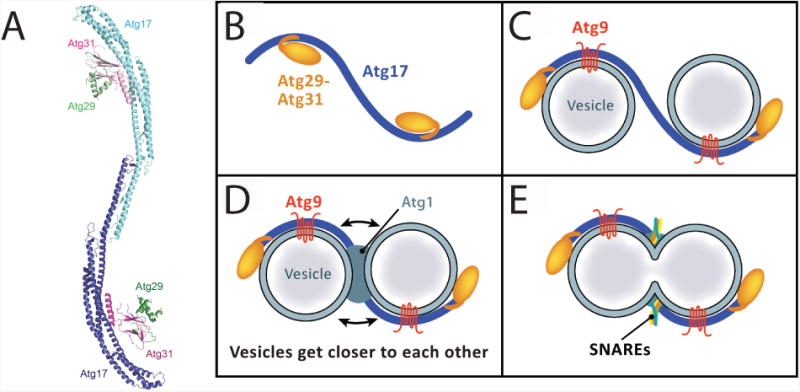

Structural model for vesicle clustering

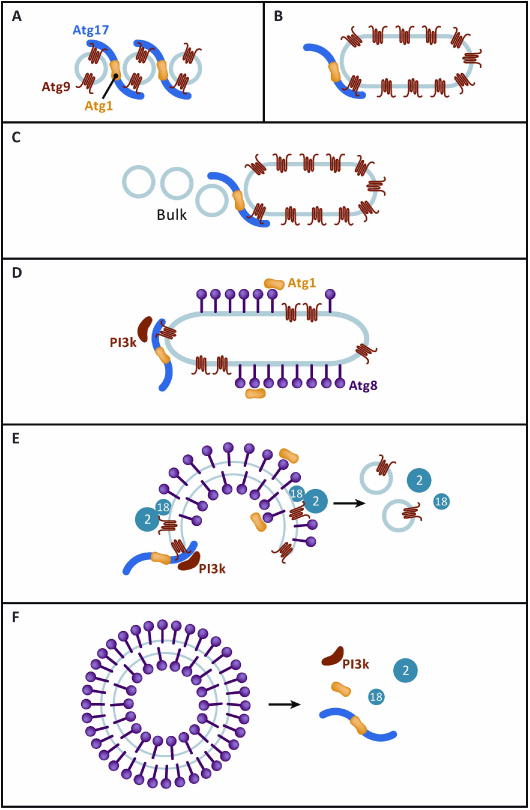

The protein kinase activity of Atg1 seems to be dispensable for the earliest autophagic events [36]. Instead, the Atg1 complex in early autophagy may act as a scaffold to organize the 20-30 nm Atg9 vesicles in a manner allowing them to fuse into a membrane sheet. This model stems from the following observations: first, Atg17 interacts directly with Atg9, an interaction required for Atg9 localization to the PAS [37]; second, the crystal structure of Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 revealed an S-shaped scaffold in which the two curves of the S are strikingly complementary to the size of the Atg9 vesicles (Fig. 4A); third, the EAT domain of Atg1 binds selectively to highly curved 20-30 nm vesicles in vitro and is capable of tethering these vesicles to each other; and fourth, the Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 subcomplex regulates the activity of the EAT domain, an indication of the interplay between the membrane-binding and membrane protein-binding elements in the complex. These data suggest that vesicles are tethered via the dimer interfaces of Atg1 and Atg17, and their binding to lipids and to Atg9, respectively (Figure 4B-D). The juxtaposition of the vesicles in this geometry places them about 20 Å apart. This does not bring them close enough to fuse on their own, but could presumably position them such that bridging SNARE complexes described below could finish the job (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

The Atg1 complex and a model for vesicle tethering. A. Crystal structure of the autoinhibited Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 complex [30]. B-E. A hypothesis for the tethering, and fusion of Atg9 vesicles by the Atg1 complex and SNAREs. For clarity Atg13 is not depicted in the cartoon B. In uninduced conditions, the Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 subcomplex resides at the PAS but does not scaffold because the Atg29-Atg31 module sterically blocks the concave surface of Atg17. C. Following autophagy induction, Atg9 vesicles migrate to the PAS, where the binding of Atg9 to Atg17 competitively displaces Atg29-Atg31. Alternatively, some other activation signal might disinhibit Atg17, leading to the subsequent binding of Atg9 vesicles to the double crescent. In this state, Atg9 vesicles are scaffolded in proximity to one another, but are not tethered tightly enough for membrane fusion. D. Atg13 is recruited to the PAS following its dephosphorylation, with the recruitment of Atg1 occurring simultaneously or subsequently. The EAT domain of Atg1 tightly tethers the two vesicles in conjunction with their preexisting scaffolding by Atg17. In the final step in this speculative model, (E), SNAREs form appropriate pairings across the gap between the two vesicles and drive their homotypic fusion.

The model outlined above provides an appealing structural framework for Atg1 complex function early in autophagy, yet raises questions as well. The putative curved vesicle binding face of Atg17-Atg31-Atg29 is blocked in the crystal structure, begging the question as to whether and how the concave face of Atg17 is liberated. Atg9 is an attractive candidate, as this would confer a high level of specificity for the nucleation of Atg9-positive vesicles over all others in the cell. In the absence of biochemical confirmation, an alternative model for Atg17-mediated tethering could be that the concave face is fortuitous and not involved in contacting Atg9 vesicles. Atg9 vesicles accumulate at the PAS in the absence of Atg1, indicating that Atg1-mediated tethering is not required for the initial clustering. It seems most likely that tethering occurs in two stages. First, Atg17 (and Atg29 and Atg31) loosely cluster Atg9 vesicles, localizing them to the PAS. Upon recruitment of Atg1 to the complex, the inter-vesicle distances might be further shortened, priming them for SNARE-mediated fusion. Clearly, many important details of these events remain to be elucidated.

A second tethering complex, the transport protein particle (TRAPP) III complex, has also been linked to the role of Atg9 vesicles in autophagosome biogenesis. The three known forms of the TRAPP complexes are multisubunit GEFs for the Rab protein Ypt1. TRAPPI and II are involved in ER and Golgi trafficking through vesicle tethering [38, 39], while TRAPPIII functions in autophagy [40-44]. The TRAPPIII complex contains the subunits Trs20, Trs23, Trs31, Bet5, and Bet3, which are common to all of the complexes, and the unique autophagy-specific subunit Trs85. Trs85 interacts directly with Atg9 and thereby activates Ypt1 on Atg9 vesicles. The TRAPPIII complex and Ypt1 are targeted to Atg9 vesicles before arriving at the PAS [45]. Once at the PAS, Ypt1-GTP has a role in targeting Atg1 by directly binding to its kinase catalytic domain [8]. Atg1 thus appears to be a coincidence detector whose targeting requires both dephosphorylated Atg13 and GTP-bound Ypt1. Classical tethering complexes like TRAPPIII operate over longer length scales [38, 46] than the short-range vesicle dimerization promoted by the Atg1 complex. It would be an elegant solution if it turned out that TRAPPIII, Atg17, and Atg1 tethered vesicles in successively closer physical proximity at successive steps in the pathway. The activation of a Rab protein by the upstream tethering complex, TRAPPIII, such that a second complex, Atg1, is recruited is also reminiscent of classical tethering pathways [38, 46].

Fusion of vesicles

The early phase of autophagosome initiation culminates with fusion of the precursor vesicles to form the phagophore. These fusion events are most likely mediated by SNARE proteins [47-49]. SNAREs are a large family of proteins that mediate the fusion of vesicles with one another or with target membranes. When complementary SNAREs on two membranes zipper into a four-helix bundle, this drives the membranes into such close proximity that fusion ensues [50]. SNARES are classified as Q-SNARES and R-SNARES, based on the presence of a conserved glutamate (Q) or arginine (R) residue in the SNARE motif. Functional bundles are composed of three Q-SNARES, Qa, Qb and Qc, and one R-SNARE. The SNAREs involved in early autophagy include members of all the appropriate classes, and thus in principle should be sufficient to drive fusion.

The Q-SNARES Sso1/2, Sec9, and Tlg2 have a major role in very early stages of autophagy initiation [49] (Fig. 3B). The absence of Sso1/2 prevents formation of the tubuovesicular Atg9 clusters discussed above. Under these conditions, Atg9 is dispersed in the cytosol in small vesicles. Because loss of these SNAREs leads to a block in Atg9 transport to the PAS, it has not been directly demonstrated that they are involved in Atg9 vesicle fusion at the PAS. Clearer evidence for a SNARE function in vesicular precursor fusion into the phagophore is seen in human cells. In HeLa cells, the importance of SNAREs in the fusion of small vesicles required for autophagosome biogenesis has been demonstrated as an accumulation of small Atg16L-positive vesicles was observed when VAMP7, syntaxin-7, syntaxin-8 and VT1B were depleted [47]. It is appealing that this collection of SNAREs includes one member of each of the essential bundle components Qa, b, c, and R. The Atg16L1 vesicles studied in HeLa cells are similar in size and might correspond to the yeast Atg9 vesicles, although this remains to be seen [48]. Additionally, this might suggest the role for a secondary population of small vesicles in addition to Atg9 vesicles for autophagosome biogenesis. This seems likely as studies in yeast have suggested that Atg9 provides only a small portion of the total membrane required for autophagosome biogenesis. Nevertheless presence of Atg16 positive vesicles suggests that mammalian phagophores originate from the fusion of a pool of small cytosolic vesicles, as in yeast, and that SNAREs are required for this fusion event.

Fusion of Atg9 vesicles into the yeast phagophore already begins at an early stage in the recruitment of Atg proteins to the PAS. This is evidenced by the formation of tubules in the absence of Atg14, as visualized by EM [19]. Atg14 is the autophagy-specific subunit of PI 3-kinase, which is recruited by the N-terminal HORMA domain of Atg13 [51]. On the other hand, when SNARE mediated fusion is blocked in human cells, the recruitment cascade can proceed at least to the stage of Atg16 [47]. Thus there does not appear to be an Atg recruitment checkpoint for membrane fusion. In other words, when fusion is frustrated, the later Atg proteins still seem to be recruited to the PAS, albeit non-productively.

From initiation to extension

Once the early fusion events are over, most of the early PAS proteins remain as a punctate complex [52]. Atg17 and the PI 3-kinase complex are among the factors that remain at the PAS during the growth of the phagophore (Fig. 5). The major protein marker for the phagophore and the most downstream Atg protein to arrive is Atg8, which is covalently conjugated to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in a ubiquitin cascade-like reaction. Atg1 binds to Atg8 via a conserved motif, which was found to be important for the stable recruitment of Atg1 to the phagophore, although it is not important for recruitment to the PAS [35, 53, 54 ]. This observation was initially surprising in that Atg1 arrives early to the PAS while Atg8 arrives much later. As the phagophore grows, however, a portion of the Atg1 pool departs from Atg17 and the PAS, following Atg8 over the phagophore [52] (Fig. 5). At this later stage of Atg1 function, its kinase activity is required [55].

Figure 5.

From initiation to extension. A speculative model for the possible continuing roles of the initiation machinery during phagophore extension. A. A recap of the initial tethering events depicted in Fig. 4(B-D). B. Following Atg9 vesicle fusion, the phagophore begins as a small membrane sheet, visualized in two-dimensional projection as a tube. C. Atg9 vesicles are estimated to provide less than 1 % of the ultimate membrane content of the autophagosome. The source and physical state of the bulk of the membrane remains a topic of controversy. It is noteworthy that the Atg1 EAT domain has no apparent specificity for different lipid compositions, sensing only high curvature. Moreover, membrane-inserting curvature sensors can bind well to loosely packed neutral lipid mixtures, such as those of the ER [12], which is widely considered the major source of lipid supply in autophagosome biogenesis. D. The Atg1 complex, via Atg13, recruits the PI 3-kinase complex, although not necessarily through a direct interaction [51]. After Atg8 conjugation begins, some of the Atg1 subunit appears to dissociate from the PAS [52] and localize to the phagophore surface via its AIM [35, 53, 54]. E. PI(3)P generated by the PI 3-kinase complex diffuses over the phagophore surface, and together with Atg9, recruits the Atg2-Atg18 complex. The Atg2-Atg18 complex, together with Atg1, somehow mediates recycling of Atg9. F. Upon autophagosome closure, the high curvature rim of the phagophore disappears, remove the binding sites for curvature-sensing proteins such as Atg17. The dissociation of these proteins might be sensed by a checkpoint for autophagosome maturation, signaling readiness for fusion with the vacuole.

Concluding remarks

The past three years of progress in understanding the structure and function of the yeast PAS have opened what is probably the clearest window available on the earliest events of autophagosome biogenesis. Having made the jump from black box to working model, many new questions have come into focus, while some older questions have acquired new urgency.

Atg9, with its central role in initiation and its six transmembrane spanning regions, is at the heart of many of these questions. Beyond acting as a marker for the select pool of vesicles that initiates the phagophore, why is Atg9 so important? What is the reason for an apparently unique and dedicated pathway for the production of Atg9 vesicles from the Golgi apparatus? After initiation, Atg9 leaves the PAS, binds to the Atg2-Atg18 complex, and is recycled out of the phagophore. Why is it so important to clear Atg9 out of the phagophore? What components of the generic endosomal recycling machinery participate in Atg9 recycling? Given that Atg17 is still resident at the PAS at this stage, what dissociates Atg9 from Atg17? Could Atg9 function as a marker for immature phagophores?

The sequence of Atg protein recruitment to the PAS is now well-defined, but the temporal coordination between the Atg and key non-Atg proteins is far less clear. It will be particularly critical to define when SNAREs, TRAPPIII, and Ypt1 appear at the PAS relative to the Atg proteins. The SNAREs required at the earliest point in yeast autophagy seem to be required for Atg9 vesicle transport prior to arrival at the PAS. While it seems natural to expect that the same SNAREs would drive Atg9 vesicle fusion at the PAS, this remains to be demonstrated.

Atg17 has been crystallized in what appears to be an inactive conformation. If this concept is correct, it begs the question as to what activates Atg17. Atg9 itself could be the activator, but roles for Rab proteins, perhaps Ypt1, protein phosphorylation, or other factors seem possible. Atg17 is predicted, but not demonstrated, to tether vesicles on the basis of its structure, while the Atg1-EAT domain has been shown biochemically to tether vesicles. It will be important to understand the structure of the EAT domain dimer and its complex with Atg13 and Atg17 in order to fully explain how vesicle tethering is coordinated. Ultimately, in vitro reconstitution of the early Atg9 vesicle fusion events by the Atg1 complex and the relevant SNAREs would provide the strongest test of current models.

Most early PAS components seem to remain in place throughout phagophore extension. This raises the question: how are generic Atg-negative vesicles directed to fuse with the growing phagophore. Based on the number and size of the Atg9 vesicles involved in initation, we estimate that >99% of the lipid in the phagophore derives from sources other than the initiating pool of Atg9 vesicles. It would seem natural that some of the same machinery involved in the initial fusion events would also be involved in bulk membrane delivery, but this concept will need to be tested.

There is strong evidence for some parallels between autophagy initiation in mammals and yeast, suggesting many of the concepts outlined here will also be relevant in mammalian cells. The EAT domain is conserved in ULK1 and ULK2, which also act very early in autophagy. The EAT domain of ULK1 can target membranes autonomously [16]. SNAREs have a similar, although not a demonstrably identical role, in early steps in mammalian and yeast autophagy. Mammalian FIP200 is a large predicted helical protein that forms a complex with ULK1, acts early in autophagy and is predicted to be the functional analog of Atg17. On the other hand, clear othology between the two has yet to be demonstrated, likely since the structure of FIP200 is unknown. Given the structural and conceptual framework for the early steps of autophagy, it will be fascinating to see how the picture is fleshed out in yeast and in mammals in coming years.

Box 1. Glossary.

PAS: Phagophore assembly site. The PAS was identified in yeast as a punctate structure to which most the Atg proteins colocalize at they start to form the phagophore. Also known as the pre-autophagosomal structure.

SNAREs: Stands for SNAp(soluble NSF Attachment Protein) Receptor. The SNAREs comprise a large family of proteins whose main role is to mediate vesicle fusion

R-SNARES: Contain a conserved Arginine in the center of the SNARE motif.

Q-SNARES: Contain a conserved Glutamine in the center of the SNARE motif. Q-SNAREs are further classified as Qa, Qb and Qc dependent upon their position in the four helix bundle.

TRAPP Complex: Transport Protein Particle Complex which was first identified as a tethering factor involved in endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport. In yeast three TRAPP complexes have been identified. TRAPIII functions in the autophagy pathway.

Highlights.

The phagophore grows from a few Atg9-positive vesicles of ∼20 nm diameter

Atg17, Atg29, and Atg31 form a structure that potentially scaffolds vesicles

Atg1 and Atg13 join Atg17 at the phagophore assembly site in starvation

The phagophore grows and closes, becoming the autophagosome

Acknowledgments

Research in the Hurley lab was supported by the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIDDK (J.H.H.), a Damon Runyon Cancer Research Fellowship (R. E. S.), and Ruth Kirschtein NRSA fellowship GM099319 (M. J. R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mizushima N, Klionsky DJ. Annu Rev Nutr. Annual Reviews; Palo Alto: 2007. Protein Turnover Via Autophagy: Implications for Metabolism; pp. 19–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy Fights Disease through Cellular Self-Digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noda T, Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y. Yeast Autophagosomes: De Novo Formation of a Membrane Structure. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubinsztein DC, Shpilka T, Elazar Z. Mechanisms of Autophagosome Biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R29–R34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. Autophagic Processes in Yeast: Mechanism, Machinery and Regulation. Genetics. 2013;194:341–361. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.149013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y. Current Knowledge of the Pre-Autophagosomal Structure (Pas) FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1280–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamasaki M, et al. Autophagosomes Form at Er-Mitochondria Contact Sites. Nature. 2013;495:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge L, Melville D, Zhang M, Schekman R. The Er-Golgi Intermediate Compartment Is a Key Membrane Source for the Lc3 Lipidation Step of Autophagosome Biogenesis. ELife. 2013 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00947. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki K, Kubota Y, Sekito T, Ohsumi Y. Hierarchy of Atg Proteins in Pre-Autophagosomal Structure Organization. Genes Cells. 2007;12:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabeya Y, Noda NN, Fujioka Y, Suzuki K, Inagaki F, Ohsumi Y. Characterization of the Atg17-Atg29-Atg31 Complex Specifically Required for Starvation-Induced Autophagy in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:612–615. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheong H, Lindsten T, Wu JM, Lu C, Thompson CB. Ammonia-Induced Autophagy Is Independent of Ulk1/Ulk2 Kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11121–11126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107969108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mcalpine F, Williamson LE, Tooze SA, Chan EYW. Regulation of Nutrient-Sensitive Autophagy by Uncoordinated 51-Like Kinases 1 and 2. Autophagy. 2013;9:361–373. doi: 10.4161/auto.23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura SI, Natsume T, Guan JL, Mizushima N. Fip200, a Ulk-Interacting Protein, Is Required for Autophagosome Formation in Mammalian Cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:497–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganley IG, Lam DH, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, Jiang X. Ulk1-Atg13-Fip200 Complex Mediates Mtor Signaling and Is Essential for Autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900573200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosokawa N, et al. Nutrient-Dependent Mtorc1 Association with the Ulk1-Atg13-Fip200 Complex Required for Autophagy. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:1981–1991. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J, Kundu M, Kim DH. Ulk-Atg13-Fip200 Complexes Mediate Mtor Signaling to the Autophagy Machinery. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:1992–2003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercer CA, Kaliappan A, Dennis PBA, Novel Human. Atg13 Binding Protein, Atg101, Interacts with Ulk1 and Is Essential for Macroautophagy. Autophagy. 2009;5 doi: 10.4161/auto.5.5.8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan EY, Longatti A, Mcknight NC, Tooze SA. Kinase-Inactivated Ulk Proteins Inhibit Autophagy Via Their Conserved C-Terminal Domains Using an Atg13-Independent Mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:157–171. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01082-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mari M, Griffith J, Rieter E, Krishnappa L, Klionsky DJ, Reggiori F. An Atg9-Containing Compartment That Functions in the Early Steps of Autophagosome Biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:1005–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi Y, Munro S. Membrane Delivery to the Yeast Autophagosome from the Golgi-Endosomal System. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2010;21:3998–4008. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-05-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto H, Kakuta S, Watanabe TM, Kitamura A, Sekito T, Kondo-Kakuta C, Ichikawa R, Kinjo M, Ohsumi Y. Atg9 Vesicles Are an Important Membrane Source During Early Steps of Autophagosome Formation. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:219–233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young ARJ, Chan EYW, Hu XW, Koch R, Crawshaw SG, High S, Hailey DW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Tooze SA. Starvation and Ulk1-Dependent Cycling of Mammalian Atg9 between the Tgn and Endosomes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3888–3900. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orsi A, Razi M, Dooley HC, Robinson D, Weston AE, Collinson LM, Tooze SA. Dynamic and Transient Interactions of Atg9 with Autophagosomes, but Not Membrane Integration, Are Required for Autophagy. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2012;23:1860–1873. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reggiori F, Tucker KA, Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ. The Atg1-Atg13 Complex Regulates Atg9 and Atg23 Retrieval Transport from the Pre-Autophagosomal Structure. Dev Cell. 2004;6:79–90. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tucker KA, Reggiori F, Dunn WA, Jr, Klionsky DJ. Atg23 Is Essential for the Cvt Pathway and Efficient Autophagy but Not Pexophagy. J Biol Chem. 2003 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309238200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen WL, Legakis JE, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg27 Is Required for Autophagy-Dependent Cycling of Atg9. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:581–593. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng JF, Nair U, Yasumura-Yorimitsu K, Klionsky DJ. Post-Golgi Sec Proteins Are Required for Autophagy in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2010;21:2257–2269. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-11-0969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato Y, Fukai S, Ishitani R, Nureki O. Crystal Structure of the Sec4p-Sec2p Complex in the Nucleotide Exchanging Intermediate State. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8305–8310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701550104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bodemann BO, et al. Ralb and the Exocyst Mediate the Cellular Starvation Response by Direct Activation of Autophagosome Assembly. Cell. 2011;144:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ragusa MJ, Stanley RE, Hurley JH. Architecture of the Atg17 Complex as a Scaffold for Autophagosome Biogenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1501–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott SV, et al. Apg13p and Vac8p Are Part of a Complex of Phosphoproteins That Are Required for Cytoplasm to Vacuole Targeting. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25840–25849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamada Y, Funakoshi T, Shintani T, Nagano K, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. Tor-Mediated Induction of Autophagy Via an Apg1 Protein Kinase Complex. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1507–1513. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephan JS, Yeh YY, Ramachandran V, Deminoff SJ, Herman PK. The Tor and Pka Signaling Pathways Independently Target the Atg1/Atg13 Protein Kinase Complex to Control Autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17049–17054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903316106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamada Y, Yoshino K, Kondo C, Kawamata T, Oshiro N, Yonezawa K, Ohsumi Y. Tor Directly Controls the Atg1 Kinase Complex to Regulate Autophagy. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1049–1058. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01344-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraft C, et al. Binding of the Atg1/Ulk1 Kinase to the Ubiquitin-Like Protein Atg8 Regulates Autophagy. EMBO J. 2012;31:3691–3703. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheong H, Nair U, Geng JF, Klionsky DJ. The Atg1 Kinase Complex Is Involved in the Regulation of Protein Recruitment to Initiate Sequestering Vesicle Formation for Nonspecific Autophagy in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19:668–681. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekito T, Kawamata T, Ichikawa R, Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y. Atg17 Recruits Atg9 to Organize the Pre-Autophogsomal Structure. Genes Cells. 2009;14:525–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai HQ, Reinisch K, Ferro-Novick S. Coats, Tethers, Rabs, and Snares Work Together to Mediate the Intracellular Destination of a Transport Vesicle. Dev Cell. 2007;12:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacher M, Kim YG, Lavie A, Oh BH, Segev N. The Trapp Complex: Insights into Its Architecture and Function. Traffic. 2008;9:2032–2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipatova Z, Belogortseva N, Zhang XQ, Kim J, Taussig D, Segev N. Regulation of Selective Autophagy Onset by a Ypt/Rab Gtpase Module. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6981–6986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121299109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynch-Day MA, Bhandari D, Menon S, Huang J, Cai HQ, Bartholomew CR, Brumell JH, Ferro-Novick S, Klionsky DJ. Trs85 Directs a Ypt1 Gef, Trappiii, to the Phagophore to Promote Autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7811–7816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meiling-Wesse K, Epple UD, Krick R, Barth H, Appelles A, Voss C, Eskelinen EL, Thumm M. Trs85 (Gsg1), a Component of the Trapp Complexes, Is Required for the Organization of the Preautophagosomal Structure During Selective Autophagy Via the Cvt Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33669–33678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nazarko TY, Huang J, Nicaud JM, Klionsky DJ, Sibirny AA. Trs85 Is Required for Macroautophagy, Pexophagy and Cytoplasm to Vacuole Targeting in Yarrowia Apolytica and Saccharomyces Rereviesioue. Autophagy. 2005;1:37–45. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou SS, et al. Modular Trapp Complexes Regulate Intracellular Protein Trafficking through Multiple Ypt/Rab Gtpases in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;191:451–U250. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.139378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kakuta S, Yamamoto H, Negishi L, Kondo-Kakuta C, Hayashi N, Ohsumi Y. Atg9 Vesicles Recruit Vesicle-Tethering Proteins Trs85 and Ypt1 to the Autophagosome Formation Site. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44261–44269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.411454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brocker C, Engelbrecht-Vandre S, Ungermann C. Multisubunit Tethering Complexes and Their Role in Membrane Fusion. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R943–R952. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moreau K, Ravikumar B, Renna M, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagosome Precursor Maturation Requires Homotypic Fusion. Cell. 2011;146:303–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moreau K, Renna M, Rubinsztein DC. Connections between Snares and Autophagy. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair U, et al. Snare Proteins Are Required for Macroautophagy. Cell. 2011;146:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sudhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane Fusion: Grappling with Snare and Sm Proteins. Science. 2009;323:474–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1161748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jao CC, Ragusa MJ, Stanley RE, Hurley JH. A Horma Domain in Atg13 Mediates Pi 3-Kinase Recruitment in Autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5486–5491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220306110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki K, Akioka M, Kondo-Kakuta C, Yamamoto H, Ohsumi Y. Fine Mapping of Autophagy-Related Proteins During Autophagosome Formation in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1242/jcs.122960. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakatogawa H, et al. The Autophagy-Related Protein Kinase Atg1 Interacts with the Ubiquitin-Like Protein Atg8 Via the Atg8 Family Interacting Motif to Facilitate Autophagosome Formation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28503–28507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C112.387514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alemu EA, et al. Atg8 Family Proteins Act as Scaffolds for Assembly of the Ulk Complex Sequence Requirements for Lc3-Interacting Region (Lir) Motifs. J Biol Chem. 2012;287 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kijanska M, Dohnal I, Reiter W, Kaspar S, Stoffel I, Ammerer G, Kraft C, Peter M. Activation of Atg1 Kinase in Autophagy by Regulated Phosphorylation. Autophagy. 2010;6:1168–1178. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]