Abstract

Background

Decision-making about liver transplant is unique in children with urea cycle disorders (UCD) and organic acidemias (OA) because of immediate high priority on the waiting list, not related to severity of disease. There is limited national outcomes data on which to base recommendations about liver transplant for UCD or OA.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of UNOS data on liver recipients <18 years, transplanted 2002–12. Repeat transplants excluded.

Results

5.4% of pediatric liver transplants were liver-only for UCD/OA. UCD/OA increased from 4.3% of transplants in 2002–05 to 7.4% in 2010–12 (p<0.0001). 96% were deceased donor. Of these, 59% were transplanted at <2 years of age. Graft survival improved as age at transplant increased (p=0.04). By 5 years post-transplant, graft survival was 78% for children <2 years at transplant and 88% for those ≥2 years (p=0.06). Vascular thrombosis caused 45% of graft losses; 65% in children <2 years. Patient survival also improved as age at transplant increased; 5-year patient survival was 88% in UCD/OA children <2 years at transplant and 99% in those ≥2 years (p=0.006). At last-follow up (54 ± 34.4 months), children transplanted for UCD/OA were more likely to have cognitive and motor delay than those transplanted for other indications. Cognitive and motor delay in UCD/OA children were associated with metabolic disorder but not predicted by age or weight at transplant, gender, ethnicity, split vs. whole liver, or hospitalization at transplant in univariate and multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Most liver transplants for UCD/OA occur in early childhood. Further research is needed on the benefits of early transplant for UCD/OA, as younger age may increase post-transplant morbidity.

Keywords: liver transplantation, children, metabolic liver disease, long-term outcomes

Background

Urea cycle disorders (UCD) and organic acidemias (OA) are inborn errors of protein metabolism, with prevalence estimated at 1:30,000 and 1:48,000–1:100,000 respectively.1–3 Within these two categories are several disorders, each a single-enzyme defect leading to the accumulation of toxic metabolites—primarily ammonia in the urea cycle disorders and various amino acids in the organic acidemias. (Table 1) Severe cases present in infancy with life-threatening metabolic decompensation, usually characterized by lethargy that progresses to coma, seizures, and multi-organ system failure. These disorders can be managed with dietary protein restriction and disorder-specific amino-acid supplements. But metabolic decompensation can recur episodically, triggered by endogenous protein loads or exogenous protein catabolism during times of stress or illness. These episodes can be fatal or cause permanent neurologic damage.

Table 1.

Classification of urea cycle disorders and organic acidemias

| Urea cycle disorders (n=186) | Organic acidemias (n=137) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Defect in 1 of 6 urea cycle enzymes | Defect in enzyme that metabolizes branched-chain amino acids, lysine, or other step in amino acid metabolism |

| Types |

|

|

Liver transplantation was identified as an alternate option for treating UCD and OA in the late 1980s. 4 The transplanted liver provides sufficient enzymatic activity to correct the deficiency, removing the risk of metabolic decompensation and the need for dietary protein restriction.5

Due to their risk of sudden life-threatening decompensation, children with UCD or OA automatically receive MELD/PELD scores of 30 at listing for liver transplant. They can be advanced to Status 1B after 30 days. Neither requires review by the Regional Review Board. This priority status was established in 2005, following initiation of the MELD/PELD scoring system in 2002.6 It is based solely on diagnosis, rather than on current life-threatening complications or severity of illness as applies to most other high-priority categories in the MELD/PELD system. This introduces unique factors into decision-making about listing for transplant and organ acceptance.7

There is limited national outcomes data on which to base recommendations about liver transplant for UCD/OA. Because these disorders are rare, they are often grouped together with other metabolic diseases in outcomes analyses.8 There is a limited evidence-base for guidelines about when these children should be transplanted to optimize long-term outcomes.9

The goals of this analysis were to describe U.S. patterns of liver transplant for children with UCD/OA, to evaluate regional and temporal variation, and to provide outcomes data about post-transplant morbidity. Although there are important biochemical and clinical distinctions between UCD and OA, we considered them both in this analysis because children with these disorders receive the same priority under current UNOS policy. The analysis differentiates them as much as possible but this was limited by sample size and diagnostic coding of the UNOS data. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Scientific Transplant and Registry (STAR) data, as retrospective data with variably missing data and limited information about cognitive and motor development, cannot definitively answer when children with UCD or OA should undergo liver transplant. But it does describe pediatric liver transplant for UCD/OA in the U.S. and raise interesting questions for future research.

Methods

This research was registered with the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco, but was IRB-exempt because no patient identifiers were accessed by the investigators.

In the UNOS STAR database, children with UCD and OA were identified by diagnostic code and then confirmed by automated text searching of primary and secondary diagnosis text fields to capture all variants of these diseases. We were able to identify all children with maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) because there is a specific associated diagnostic code and to differentiate those with UCD from those with OAs based on text searching. However, because most of these children are coded as “metabolic disease-other” with variable detail about specific diagnosis provided, we were not able to accurately classify children further within these categories. Children with other indications for transplant were categorized based on coded diagnosis. Children with acute liver failure and tumor were combined because of their high waitlist priority, status 1A and 1B respectively.

Our retrospective cohort included all recipients of first liver transplants between 2002 and 2012 that were less than 18 years old at time of transplant and transplanted after the MELD/PELD score was instituted. Children undergoing repeat transplants were excluded.

Chi-squared testing was used to compare categorical variables, and Kruskal-Wallis testing for comparison of continuous variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to examine relationships between percentage of regional transplants done for UCD/OA, waiting list mortality, and wait times. Non-parametric testing was chosen because of the skewed nature of several variables of interest (e.g. age, weight at transplant) and the small sample sizes for the UCD/OA children and number of regions. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards modeling were used to identify factors associated with graft and patient survival. No significant interactions were detected in multivariate survival analysis. Logistic regression was used to evaluate risk factors for cognitive and motor delay during follow-up. Variables with p<0.15 in univariate analysis were retained in multivariate analysis. In the multivariate model for post-transplant patient survival, diagnosis of UCD vs. OA was also forced into the model. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses used Stata 12 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

The UNOS database includes information about functional status at listing, transplant, and follow-up for children older than 1 year. Data about cognitive and motor delay are collected in UNOS follow-up data requests but not listing/transplant questionnaires. For both cognitive and motor delay, the follow-up questionnaires ask whether there is definite, probable, questionable, or no delay/impairment. Information about functional status, cognitive delay, and motor delay was included in the analysis as available.

Results

Of 5,672 pediatric liver transplants in the U.S. between 2002 and 2012, 323 were for UCD/OA. This includes 17 children who underwent liver-kidney transplant for organic acidemias. During the study period, 8 children with UCD/OA died on the liver transplant waiting list, 2.1% of those listed. Six of 8 waiting list deaths were in children ≤2 years at listing; causes of death were multi-organ system failure (n=4) and unknown (n=4). Four children who died on the waiting list had carbamyl phosphate synthetase deficiency, 2 ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, and 2 maple syrup urine disease. Median waiting list time prior to death for these patients was 36 days (IQR 13–63 days).

The proportion of pediatric liver transplants performed for UCD/OA increased from 4.3% in 2002–05 to 7.4% in 2010–12 (p<0.0001). UNOS Region 2 (Delaware, D.C., Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Northern Virginia and West Virginia) and Region 5 (Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah) accounted for 48% of UCD/OA transplants, with 87 and 59 respectively, but only 33% of pediatric liver transplants overall. The number of UCD/OA transplants in other regions during the study period ranged from 9 to 32.

Overall, 79% of UCD/OA children underwent liver transplant in their presumed home region (recipient state of residency at listing was in region where transplant done). Out-of-region liver transplants were most common in region 2, accounting for 41% of all UCD/OA transplants. In region 5, 17% of liver-only transplants for UCD/OA were on out-of-region residents—which was similar to other regions. For liver-kidney recipients, 9 of 17 were done in region 5; 78% of these were in-region transplants. Thus, the large number of UCD/OA transplants in regions 2 and 5 may represent a combination of UCD/OA disease distribution and patient travel to specific centers.

Only 4% of children with UCD/OA underwent living-donor liver transplant—vs. 16% for biliary atresia, 8.5% for children with other metabolic/cholestatic liver diseases, and 12% for children with acute liver failure or tumor (p<0.0001). The proportion of UCD/OA recipients with living donors decreased slightly over the study period: 7% in 2002–2005 (6 of 84) vs. 2.8% in 2010–2012 (3 of 107) but numbers were small (p=0.43). The 13 living-donor recipients did not differ by age at transplant, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, or days on the waiting list from deceased-donor UCD/OA recipients. Six of the 13 were transplanted in Region 2.

Children who received deceased-donor liver transplant for UCD/OA were more likely to be male and Caucasian than children transplanted for other indications, and the majority were <2 years of age at transplant (Table 2). Of children transplanted for UCD, 34% were females. During the study period, there were no significant temporal trends in proportion of UCD/OA transplants at ≤ 2 years (p=0.38) or median age at transplant (1 year, IQR 0–6, p=0.35). The proportion of UCD/OA children transplanted before age 1 did vary substantially by region—from 14% in region 3 to 56.5% in region 4. In Region 2, 18% of UCD/OA children were transplanted before age 1; versus 46% in Region 5 (p=0.03, includes all regions).

Table 2.

Pediatric deceased-donor liver transplant recipient demographics by diagnosis, UNOS data 2002–2012

| UCD/OA | Biliary atresia | Other cholestatic/metabolic diseases* | Acute liver failure/tumor | p† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 293 | 1571 | 1983 | 1036 | |

| Male, n (%) | 181 (62%) | 625 (40%) | 1004 (51%) | 581 (56%) | <0.0001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 191 (65%) | 728 (46%) | 1116 (57%) | 496 (48%) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 24 (8%) | 335 (21%) | 342 (17%) | 172 (17%) | |

| Hispanic | 49 (17%) | 329 (21%) | 299 (20%) | 290 (28%) | |

| Asian | 25 (9%) | 113 (7%) | 66 (3%) | 48 (4%) | |

| Other‡ | 4 (1%) | 66 (4%) | 60 (3%) | 30 (3%) | |

| Age at transplant, n (%) | |||||

| <1 year | 97 (33%) | 749 (48%) | 391 (20%) | 128 (12%) | <0.0001 |

| 1–2 years | 77 (26%) | 492 (31%) | 492 (25%) | 265 (26%) | |

| 3–6 years | 52 (18%) | 113 (7%) | 244 (12%) | 217 (21%) | |

| 7–11 years | 41 (14%) | 118 (8%) | 293 (15%) | 159 (15%) | |

| 12–17 years | 26 (9%) | 89 (6%) | 563 (28%) | 267 (26%) | |

| Status at transplant, n (%) | |||||

| MELD/PELD | 151 (52%) | 1392 (89%) | 1590 (80%) | 263 (25%) | <0.0001 |

| Status 1B | 142 (48%) | 65 (4%) | 133 (7%) | 151 (15%) | |

| Status 1A | 0 | 112 (7%) | 260 (13%) | 622 (60%) | |

| MELD/PELD lab score at transplant | −3 (−7 – 3) | 16 (8–23) | 20 (1–31) | 15 (7–24) | <0.0001 |

| Transplant type, n (%) | |||||

| Whole liver | 250 (85%) | 1208 (77%) | 1787 (90%) | 829 (80%) | <0.0001 |

| Split liver | 43 (15%) | 363 (23%) | 196 (10%) | 207 (20%) | |

| Months of post-transplant follow-up, median (IQR) | 36.3 (12.1–72.6) | 43.1 (12.2–83.6) | 43.3 (12.3–79.1) | 34.1 (10.9–70.3) | <0.0001 |

Other metabolic conditions include: Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Crigler-Najjar syndrome, cystic fibrosis, glycogen storage disease, inborn errors in bile acid metabolism, neonatal hemochromatosis, primary hyperoxaluria, tyrosinemia, Wilson’s disease (non-fulminant failure), mitochondrial diseases, familial hypercholesterolemia, cholesterol ester storage defects, Niemann-Pick, glycogen storage disorders. Other cholestatic conditions include: Alagille syndrome, progressive intrahepatic cholestatic syndromes (including Byler), total parenteral nutrition cholestasis, sclerosing cholangitis, and idiopathic cholestasis.

p-value by chi-square testing for categorical variables, Kruskal-wallis testing for continuous variables.

Other ethnicity includes Native American, Alaskan, Pacific Islander, Hawaiian, Multi-racial, and Unknown.

In UCD/OA deceased donor recipients, the median weight at transplant was 12.6 kg (IQR 8.6–21.1kg, n=273 with weight available) with no significant changes over time (p=0.14). Only 3% of UCD/OA recipients underwent transplant at less than 5 kg, 33% at 5–10 kg, and 38% at 10–20 kg. There was some variation in median weight at transplant between region, ranging from 8.5 kg (IQR 7.1–18.6kg) in region 6 to 17.4 kg (IQR 10.4–24.0 kg) in region 3 (p=0.03). Region 2 median weight was 14.8 kg (IQR 9.5–26.1 kg), and Region 5 was 10.5 kg (IQR 8.4–15.4 kg).

Of the 116 children who received deceased-donor transplants for OA, 59% were for maple syrup urine disease (MSUD). Children with MSUD were older than other UCD/OA children at transplant, with 28% <2 years at transplant and 46% 7–17 years at transplant. They consequently had higher median weights at transplant (22.4kg, IQR 14.4–43.3) than children with UCD (7.5kg, IQR 7.5–16.8kg) and other OAs (13.6kg, IQR 10.3–20.7kg, p<0.0001). There was no significant difference in gender distribution between MSUD children and those with UCD or other OAs (p=0.20). Children with MSUD were more likely to be Caucasian (69%, vs. 67% for UCD, 54% other OAs) and less likely Hispanic or Asian (p=0.02). Sixty-three percent of all MSUD transplants were done in region 2.

Of note, children receiving liver-kidney transplant all had methylmalonic acidemia (MMA) (n=17) and were all transplanted over the age of 3, with 53% age 12–17 at transplant. 88% received whole-liver transplants. Median post-transplant follow-up time was 2.9 years (IQR 0.9–5.2 years).

UNOS policy changed in 2005 to allow UCD/OA children to be listed as Status 1B after 30 days on the waiting list. Subsequently, the proportion of UCD/OA children transplanted at status 1B increased over time, from 35% in 2006–2009 to 63% in 2010–2012 (p<0.0001). There was no change in median days on the waiting list for UCD/OA children over this time period: 69 days (IQR 26–180) in 2002–2005, 68 days (IQR 32–212) in 2006–2009, and 60 days (36–131) in 2010–2012 (p=0.91). Of note, region 2 had significantly longer waitlist times for children transplanted by MELD/PELD (285 days, IQR 161–453, n=36) than other regions (25 days, IQR 13–122, n=75), although waiting times for those transplanted at Status 1B were similar (region 2: 87 days, IQR 52–130, n=23; all other regions: 66 days, IQR 45–101, n=81). Eighty percent of the 34 children in region 2 that waited for >30 days and were transplanted by MELD/PELD had maple syrup urine disease. They all received whole liver transplants.

In multivariate logistic regression of UCD/OA deceased donor recipients, excluding region 2, age<1 year increased the odds of being transplanted at Status 1B (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.8–10.1, p<0.0001) after controlling for year of transplant, diagnosis, gender, ethnicity, weight at transplant, and median regional waiting time. Other variables were not significant. Including children from region 2 did not change the OR associated with age <1 year substantially.

The percentage of regional pediatric liver transplants done for UCD/OA did not correlate with regional death rate on the waiting list (r=0.31, p=0.36) or the regional ratio of deaths to transplants (r=0.44, p=0.18) for non UCD/OA children. By region, median days on the waiting list for non-UCD/OA children did increase as the percentage of pediatric transplants done for UCD/OA increased (r=0.76, p=0.007). UCD/OA children who received deceased-donor transplants overall spent less time on the waiting list (median 67 days, IQR 32–175 days) than those with biliary atresia (83 days, IQR 32–195 days) or other metabolic/cholestatic diseases (73 days, IQR 22–196 days, p=0.02). Among children transplanted at status 1B, children with UCD/OA waited longer (median 60 days, 39–107 days) than those with ALF/tumor (44 days, 29–106 days) and other metabolic diseases (49 days, 17–102 days) but approximately the same as those transplanted for biliary atresia (62 days, 24–136 days, p=0.0002).

Compared to other children who received a deceased donor liver, children with UCD/OA were more likely to get a whole liver than those with biliary atresia or tumor but less likely than those with other metabolic/cholestatic diseases. (Table 2) This pattern was the same for those transplanted at MELD/PELD and at Status 1B. Status at transplant was not associated with receiving a whole liver in univariate or multivariate analysis (data not shown).

Graft survival in UCD/OA deceased donor recipients

Median total patient follow-up time for UCD/OA deceased donor recipients was 3.0 years (IQR 1.0–5.9 years). For UCD/OA children, graft survival was 92% at 30 days, 89% at 1 year, and 83% at 5 years. This was similar to graft survival in children with biliary atresia (91% at 30 days, 88% at 1 year, 83% at 5 years) and better than graft survival for those with other metabolic/cholestatic conditions (95% at 30 days, 86% at 1 year, 75% at 5 years) (p<0.0001).

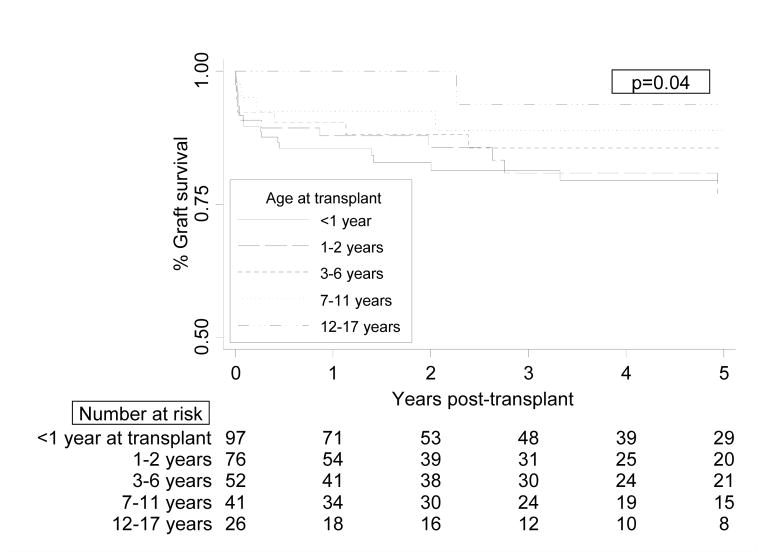

Overall, graft survival in UCD/OA children improved as age at transplant increased (p=0.04, Figure 1). There was no graft survival difference between those children <1 year and 1–2 years at transplant (p=0.93 for overall survival difference). By 5 years post-transplant, graft survival was 78% for children <2 years at transplant and 88% for those ≥2 years (p=0.06 for overall survival difference). MSUD children had lower rates of graft loss (6%) than those with UCD (18%) or other OAs (15%, p=0.05).

Figure 1.

Graft survival in children who received liver transplants for urea cycle disorders or organic acidemias, by recipient age at transplant. Includes recipients of deceased donor livers only. p=0.04 by Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis.

Among 43 deceased donor recipients with graft loss, reported causes included: vascular thrombosis (n=19), primary graft non-function (n=7), infection (n=2), biliary complications (n=3), and acute rejection (n=2). 45% of graft losses occurred within 2 weeks of transplant. Of the 19 children with vascular thromboses, 40% were less than 1 year at transplant and another 25% were 1–2 years. Eighty percent had received a whole liver. Vascular thromboses accounted for 41% of graft loss in UCD children and 55% in OA children. In 10 patients with no cause of graft loss reported, 60% lost their graft at 1–6 months post-transplant.

In multivariate analysis of graft survival in children who underwent deceased donor liver transplant for UCD/OA, females and Hispanics were at higher risk of graft loss. Younger age and lower weight increased risk of graft loss in univariate but not multivariate analysis. Though MSUD children had better graft survival than both UCD and OA children in univariate analysis, there were no significant differences after controlling for age at transplant and other factors in multivariate analysis. (Table 3) Including UCD/OA children that received living-donor liver transplant did not change significant predictors of graft survival.

Table 3.

Risk factors for post-transplant graft loss in UCD/OA deceased-donor liver transplant recipients

| Univariate HR | p* | Multivariate HR | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age<2 years at transplant | 1.77 (0.95–3.3) | 0.07 | 1.10 (0.45–2.71) | 0.84 |

| Female | 1.54 (0.84–2.81) | 0.15 | 1.97 (1.01–3.85) | 0.05 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | REF | REF | ||

| Black | 2.04 (0.76–5.44) | 0.15 | 2.07 (0.76–5.64) | 0.15 |

| Hispanic | 3.35 (1.68–6.64) | 0.001 | 3.63 (1.74–7.56) | 0.001 |

| Asian | 1.22 (0.36–4.11) | 0.75 | 0.99 (0.29–3.45) | 0.99 |

| Other† | 2.59 (0.34–19.35) | 0.35 | 1.68 (0.21–13.4) | 0.31 |

| Weight at transplant (kg) | 0.97 (0.94–1) | 0.06 | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.31 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Urea cycle disorder | REF | REF | ||

| MSUD | 0.31 (0.11–0.89) | 0.03 | 0.44 (0.14–1.34) | 0.15 |

| Organic acidemia (non-MSUD) | 0.88 (0.39–2.01) | 0.77 | 0.73 (0.30–1.75) | 0.48 |

| Split liver (vs. whole) | 1.86 (0.91–3.77) | 0.09 | 1.31 (0.62–2.79) | 0.48 |

| Cold ischemia time (hrs) | 1.00 (0.91–1.1) | 0.92 | ||

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2002–2005 | REF | |||

| 2006–2009 | 0.75 (0.37–1.52) | 0.43 | ||

| 2010–2012 | 0.93 (0.42–2.06) | 0.87 | ||

| Hospitalized at transplant | 1.53 (0.73–3.18) | 0.26 | ||

| Status at transplant | ||||

| MELD/PELD 30 | REF | |||

| Status 1B | 1.00 (0.55–1.83) | 0.98 |

p-value from Cox proportional hazards models

Other ethnicity includes Native American, Alaskan, Pacific Islander, Hawaiian, Multi-racial, and Unknown.

For the 17 liver-kidney recipients, all of whom had MMA, only 1 patient (6%) lost their liver graft during follow-up. The cause was hepatic artery thrombosis, and the patient was re-transplanted 15 days after initial liver-kidney transplant. Ten other children with MMA received liver-only transplants; 80% were ≤2 years of age at transplant. In this group, 1 patient lost their graft at 13 days post-transplant to vascular thrombosis, and was re-transplanted. There were no deaths during follow-up. None of the 27 children with MMA had previous kidney transplant prior to their liver or liver-kidney transplant.

Patient survival in UCD/OA deceased donor recipients

In UCD/OA deceased donor recipients, patient survival was 99% at 30 days, 96% at 1 year, and 95% at 5 years. This was similar to survival in biliary atresia recipients (97% at 30 days, 95% at 1 year, 93% at 5 years) and better than those transplanted for other metabolic/cholestatic conditions (96% at 30 days, 89% at 1 year, and 81% at 5 years (p<0.0001).

Overall, patient survival improved as age at transplant increased, with no post-transplant deaths occurring in children >4 years old at transplant (p=0.008 for trend). Five-year patient survival was 88% in UCD/OA deceased donor recipients <2 years at transplant and 99% in those ≥2 years (p=0.006). Of the 14 post-transplant deaths, 57% occurred within 6 months post-transplant. Reported causes of death included: multi-organ system failure (n=5), sepsis/infection (n=4), primary graft non-function (n=2), respiratory failure/cardiac arrest (n=1), post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (n=1), and “metabolic crisis” (n=1).

In univariate analysis, age < 2 years at transplant, split liver, and Hispanic ethnicity increased the risk of post-transplant death (Table 4). OA was not associated with higher risk of graft loss or mortality than UCD in univariate or multivariate analysis. No children with MSUD died during post-transplant follow-up; thus only UCD vs. OA was considered for mortality analysis. Higher weight at transplant was protective against death in univariate analysis (Table 4), but the risk was not significantly different between those 5–10 kg vs. 10–20 kg at transplant (HR 0.46, 0.15–1.3, p=0.19, n=194). In multivariate analysis, only Hispanic ethnicity increased mortality risk. Power was limited because of the small number of deaths.

Table 4.

Risk factors for post-transplant mortality in UCD/OA deceased-donor liver transplant recipients

| Univariate HR | p | Multivariate HR | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age<2 years at transplant | 6.34 (1.42–28.39) | 0.02 | 0.97 (0.12–7.98) | 0.97 |

| Female | 0.72 (0.22–2.32) | 0.59 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | REF | REF | ||

| Black | 3.43 (0.66–17.72) | 0.14 | 3.79 (0.72–19.95) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic | 5.91 (1.79–19.48) | 0.004 | 4.73 (1.35–16.54) | 0.02 |

| Asian | 1.6 (0.18–13.72) | 0.67 | 1.36 (0.15–12.03) | 0.78 |

| Other† | ||||

| Weight at transplant (kg) | 0.87 (0.77–0.98) | 0.02 | 0.86 (0.71–1.05) | 0.14 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Urea cycle disorder | REF | REF | ||

| Organic acidemia‡ | 0.41 (0.11–1.46) | 0.17 | 0.69 (0.16–2.97) | 0.62 |

| Split liver (vs. whole liver) | 3.62 (1.21–10.82) | 0.02 | 2.25 (0.72–7.03) | 0.17 |

| Cold ischemia time (hours) | 0.96 (0.8–1.16) | 0.72 | ||

| Year of transplant | ||||

| 2002–2005 | ||||

| 2006–2009 | 0.89 (0.27–2.96) | 0.86 | ||

| 2010–2012 | 0.77 (0.17–3.45) | 0.74 | ||

| Hospitalized at transplant | 0.93 (0.21–4.19) | 0.94 | ||

| Status at transplant | ||||

| MELD/PELD 30 | REF | |||

| Status 1B | 0.88 (0.3–2.54) | 0.82 |

p-value from Cox proportional hazards models

Other ethnicity includes Native American, Alaskan, Pacific Islander, Hawaiian, Multi-racial, and Unknown.

There were no deaths among MSUD patients post-transplant, so this diagnostic category was not considered separately for mortality analysis.

Hispanic children had a higher overall prevalence of OA (57%) than children of other ethnicities: White (38%), Black (25%), Asian (36%) (p=0.02), and a lower prevalence of MSUD However, Hispanic ethnicity remained a predictor or mortality even after controlling for diagnosis(Table 4) There was no difference in age distribution at transplant by ethnicity (p=0.16). Region and insurance type were not associated with graft loss or survival; adjusting for them did not attenuate the association between Hispanic ethnicity and poor outcomes. When considering deceased donor pediatric recipients transplanted for all indications, Hispanic ethnicity did not increase graft loss or mortality risk in univariate or multivariate analysis (data not shown).

Cognitive and motor delay post-transplant

In the UNOS database, data about cognitive and motor delay are collected in post-transplant but not pre-transplant records. Information from follow-up records at less than 7 months post-transplant was used as our best available indication of pre-transplant status. Children transplanted for UCD/OA were significantly more likely to have definite or probable cognitive and motor delay, at both first and last post-transplant follow-up, than children transplanted for other indications. (Table 5) Reported prevalence of cognitive and motor delay was significantly lower for MSUD children and higher for other OA children at all time points, compared to UCD. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Cognitive and motor delays after pediatric liver transplant, by diagnosis*

| Months post-transplant (mean, SD) | UCD/OA (n, %) | Biliary atresia | Other metabolic/cholestatic diseases† | Acute liver failure/tumor | p‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive delay§ | 1st post-transplant follow-up | 5.8 ± 0.9¶ | 40.2% (n=102) | 7.2% (n=501) | 10.9% (n=559) | 8.2% (n=331) | <0.0005 |

| UCD: 42.6% (n=61) OA: 71.4% (n=14) MSUD: 18.5% (n=27) |

0.004 | ||||||

| Last post-transplant follow-up | 54 ± 34.4¶ | 42.0% (n=235) | 5.9% (n=1419) | 13.6% (n=1571) | 8.9% (n=836) | <0.0005 | |

| UCD: 40.7% (n=140) OA: 77.8% (n=36) MSUD: 22.0% (n=59) |

<0.0005 | ||||||

| Motor delay§ | 1st post-transplant follow-up | 5.8 ± 0.9¶ | 35.9% (n=103) | 10.9% (n=510) | 13.4% (n=568) | 6.7% (n=330) | <0.0005 |

| UCD: 37.1% (n=62) OA:85.7% (n=14) MSUD: 7.4% (n=27) |

<0.0005 | ||||||

| Last post-transplant follow-up | 54 ± 34.4¶ | 29.3% (n=236) | 4.0% (n=1459) | 9.4% (n=1606) | 6.1% (n=842) | <0.0005 | |

| UCD: 29.9% (n=144) OA: 55.9% (n=34) MSUD: 12.1% (n=58) |

<0.0005 |

Includes living and deceased donor recipients, <18 years of age at transplant. UNOS STR database only includes information on cognitive and motor delay in post-transplant follow-up.

Other metabolic conditions include: Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, Crigler-Najjar syndrome, cystic fibrosis, glycogen storage disease, inborn errors in bile acid metabolism, neonatal hemochromatosis, primary hyperoxaluria, tyrosinemia, Wilson’s disease (non-fulminant failure), mitochondrial diseases, familial hypercholesterolemia, cholesterol ester storage defects, Niemann-Pick, glycogen storage disorders. Other cholestatic conditions include: Alagille syndrome, progressive intrahepatic cholestatic syndromes (including Byler), total parenteral nutrition cholestasis, sclerosing cholangitis, and idiopathic cholestasis.

p-value for difference in prevalence of cognitive/motor delay, by chi-squared testing.

Includes children identified as having “probable” or “definite” delay.

No significant differences in months post-transplant for UCD compared to OA and MSUD within UCD/OA category for any follow-up period.

At last follow-up, the prevalence of cognitive delay in UCD/OA children did not differ by age at transplant. Definite or probable cognitive delay was reported in 43% of those transplanted at <2 years (n=114) and 41% of those transplanted at ≥2 years (n=121) (p=0.70). Motor delay was slightly more likely to persist at last follow-up in UCD/OA children transplanted at <2 years (35%, n=117) than those transplanted at ≥2 years (24%, n=122, p=0.06).

In multivariate analysis, MSUD was associated with decreased risk of cognitive delay (HR 0.29, 0.12–0.69, p=0.005) and motor delay (HR 0.33, 0.13–0.89, p=0.03) and other OAs were associated with increased risk of cognitive delay (HR 6.09, 2.40–15.4, p<0.0005) and motor delay (HR 3.26, 1.36–7.76, p=0.008) compared to UCD. Neither cognitive nor motor delay at last follow-up were predicted by age or weight at transplant, gender, ethnicity, split vs. whole liver, or hospitalization at transplant in uni- or multivariate analysis, before or after controlling for UCD vs. MSUD vs. other OA diagnosis (data not shown). Children transplanted at status 1B were more likely to have motor delay (36% of 113) at last follow-up than those transplanted at MELD/PELD 30 (22% of 125) in univariate (p=0.02) and multivariate analysis (OR 1.89, 0.99–3.56, p=0.05). Status at transplant was not associated with cognitive delay at last follow-up.

Functional status pre and post-transplant

Children older than 1 year had data on age-adjusted functional limitations and need for assistance with activities of daily living recorded at transplant and follow-up. Of those with data available at transplant (n=2,562), those transplanted for UCD/OA were less likely to have significant functional limitations/assistance needs (8.5% of 153) than those with biliary atresia (16% of 626), other metabolic/cholestatic disease (21% of 1176), or ALF/tumor (42% of 607) (p<0.0001). At last follow-up (n=3,861), those with UCD/OA had a higher risk of significant functional limitations/assistance needs (6.5% of 232) than those with biliary atresia (1.9% of 1374) but comparable to those with other metabolic/cholestatic diseases (7.0% of 1465) and ALF/tumor (5.3% of 790) (p<0.0001).

Discussion

Urea cycle disorders and organic acidemias are growing indications for pediatric liver transplant in the U.S. Most children who undergo liver transplant for these disorders do so before the age of 2, but the median age at transplant varies by region and by diagnosis. Graft and patient survival are generally excellent; they match or exceed that of children transplanted for other indications.10,11,8 The majority of post-transplant morbidity and mortality occurs within the first few months after transplant. The youngest children are at highest risk for post-transplant graft loss and mortality; this is likely related to age and size, not transplant indication. After controlling for age and weight at transplant, graft and patient outcomes did not differ by diagnosis within the UCD/OA cohort, although developmental delay prevalence did vary considerably.

The very low prevalence of living-related liver transplantation (LRLT) for UCD/UA in our cohort, with lowest prevalence after 2005, is likely related to the automatic high priority status received by these children. LRLT is more commonly utilized for UCD/OA in other countries. Most reports on LRLT for UCD/OA are from Japan because deceased donors are not utilized there. They report satisfactory outcomes in case series of donors from both parents and known heterozygous donors. Most of their LRLTs are performed in children 1–5 years of age, at weights of 10–20kg, with similar patient survival to the UNOS data presented here.12–14 To assess the safety of living-related donors, these reports have recommended liver biopsy or other testing to prove normal activity of the affected enzyme in potential donors, particularly parents who are presumed heterozygous carriers.13,15

LRLT could be a reasonable option for more U.S. children with UCD or OA in need of liver-only transplant. Considering LRLT for those patients that do have feasible living donors would still allow early transplant to prevent future decompensation episodes or neurocognitive delay while increasing overall organ availability. If LRLT is considered for these children, donor enzymatic activity must be assessed—particularly for presumably heterozygous parents and for disorders in which there is significant enzyme activity outside the liver, as in MMA and PA.

UCD/OA deceased donor recipients are more likely to receive whole livers than children with biliary atresia. Unfortunately we did not have information on transplant offers to evaluate whether centers turn down split liver offers for UCD/OA children because they have high waitlist priority but tend to be medically stable while waiting. Our data showed no increased risk of graft loss or mortality in UCD/OA children that received split livers, in parallel with a recent UNOS analysis of all pediatric liver transplant recipients.16 Thus, increased use of split livers in UCD/OA children may be another way to optimize utilization of deceased donor organs without delaying liver transplant in these children.

Proponents of liver transplant for UCD and OA have generally recommended transplant in early childhood to prevent morbidity and mortality from further metabolic decompensation episodes.17–19 Eight children in our analysis did die while waiting for transplant, reinforcing the potentially lethal nature of these disorders. Recent expert consensus guidelines recommend liver transplant between 3 and 12 months of age, once the child weighs more than 5 kilograms.5 Our data suggests that children transplanted at the youngest ages appear to have the highest risk of graft loss—often related to technically difficult vessel anastomoses with subsequent thrombosis in small children. Post-transplant mortality was low, but the risk of death was higher in younger children. This risk is not unique to children with UCD/OA, but raises interesting questions about optimal timing for transplant in this group. This finding may also represent a selection bias, as those children with significant neurologic injury or other systemic impairments that became evident with age may not have received liver transplants.

Interestingly, neither age, weight at transplant, nor diagnosis within the UCD/OA group (UCD vs. OA vs. MSUD) were significant predictors of post-transplant graft loss or mortality in multivariable analysis. This suggests that transplant centers may be successfully balancing age. size, and diagnosis considerations in deciding when to transplant UCD/OA children. For example, we found that children with MSUD are generally transplanted much later than children with other OAs or UCD but their prevalence of developmental delays was much lower in long-term follow–up. Interestingly, after controlling for age and other variables, MSUD was not associated with better graft or patient survival. UNOS prioritization does not currently differentiate between MSUD and the other OAs, but our analysis suggests that decision-making about optimal age at transplant differs regionally. Further research and discussion is needed to optimize prioritization policies for these related but biochemically and clinically distinct disorders.

Hispanic ethnicity was the only significant predictor of both graft loss and mortality in multivariate analysis. We were not able to identify why Hispanic UCD/OA deceased donor recipients were at increased risk for graft loss and mortality. Differences in UCD vs. OA diagnosis by ethnicity, age at transplant, region, insurance type, and the other variables included in multivariate analysis did not explain this association.

Our analysis echoes previous single-center studies demonstrating that developmental delays are common in UCD/OA liver transplant recipients, and that liver transplant halts but does not reverse associated cognitive and motor delays.14,20,21 One justification for early liver transplant in UCD/OA is prevention of developmental delays. Developmental delays during follow-up differed significantly within the UCD/OA cohort, with MSUD children being at lowest risk and other OA children at highest risk. However, after controlling for diagnosis, our data showed that younger age at transplant did not decrease prevalence of cognitive or motor delays in long-term follow-up.

Unfortunately the UNOS database does not include information on pre-transplant severity of UCD/OA or factors associated with developmental delay risk—for instance, peak ammonia level or number of decompensation episodes/hospitalizations. We lacked baseline data in younger children and had further missing data in available follow-up data. Thus, we could not assess whether early transplant was chosen for the most severely affected children and may have prevented worse long-term outcomes. Questions on developmental delay in the UNOS baseline and follow-up surveys are fairly subjective; evaluation is not rigorously standardized across all reporting centers.

Further prospective research with more standardized testing would be helpful for assessing neurocognitive benefits of early liver transplant. Comparing a post-transplant cohort to current children with UCD/OA that do not undergo liver transplant would also improve our understanding of the neuroprotective potential of liver transplant—although we acknowledge that controlling for disease severity would be very difficult. More detailed neuro-cognitive follow-up might also help determine whether early liver transplant for UCD/OA could decrease long-term prevalence of developmental delay and functional limitations—instead of stabilizing them as observed in our analysis.

Other limitations of this analysis were also due to the retrospective nature of our study. The sample size was relatively small with few post-transplant deaths. We were limited to risk factors and outcomes assessed in the UNOS database. Because of diagnostic coding within the database, we could not separately analyze outcomes for each disorder within the UCD/OA cohort. It remains difficult to objectively assess donor quality for pediatric liver transplant recipients based on UNOS data, as there is no pediatric-specific donor risk index.22 We did not have data about wait list offers for these children. Thus, we can offer limited insight into whether decision-making about organ acceptance differs for children transplanted for UCA/OA compared to other indications. Our analysis also does not control for transplant center volume and specific experience with UCD/OA liver transplants—which did vary across regions as described.

This analysis does represent the largest, and most comprehensive, cohort of children transplanted for UCD/OA. It confirms that post-transplant graft and patient survival for these children is excellent, but that further research is needed to clarify the risks and benefits associated with early transplant. Early liver transplant for UCD/OA children ideally minimizes their mortality risk and maximizes their neurodevelopmental potential, but consideration of transplant-associated risks is also important for optimal decision-making in this population.

Acknowledgments

The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the AGA, the NIH, or the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trades names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Grants and financial support: This project was supported by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Emmet B. Keeffe Career Development Award in Clinical or Translational Research in Liver Disease (Dr. Perito), NIH/NCRR UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131 (UNOS Data), and Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C (UNOS Data).

ABBREVIATIONS

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IQR

Inter-quartile range

- LRLT

living-related liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for end-stage liver disease

- PELD

Pediatric end-stage liver disease

- OA

Organic acidemia

- SD

Standard deviation

- STAR

Scientific Transplant and Registry

- UCD

Urea cycle disorder

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lanpher B, Gropman A, Chapman KA, et al. Urea cycle disorders overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, et al., editors. GeneReviews™[Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2013. Jun 24, 1993–2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1217/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrillo-Carrasco N, Venditti C. Propionic acidemia. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, et al., editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2013. Jun 24, 1993–2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92946/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manoli I, Venditti C. Methylmalonic acidemia. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, et al., editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet] Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2013. Jun 24, 1993–2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1231/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitington PF, Alonso EM, Boyle JT, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21 (Suppl 1):112–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005317909946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haberle J, Boddaert N, Burlina A, et al. Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:32-1172-7-32. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDiarmid S, Gish RG, Horslen S, Mazariegos GV. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception for unusual metabolic liver diseases. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12 Suppl 3):S124–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross LF. An ethical and policy analysis of elective transplantation for metabolic conditions diagnosed by newborn screening. J Pediatr. 2010;156(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnon R, Kerkar N, Davis MK, et al. Liver transplantation in children with metabolic diseases: The Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(6):796–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vockley J, Chapman KA, Arnold GL. Development of clinical guidelines for inborn errors of metabolism: Commentary. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;108(4):203–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morioka D, Kasahara M, Takada Y, et al. Current role of liver transplantation for the treatment of urea cycle disorders: A review of the worldwide English literature and 13 cases at Kyoto University. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(11):1332–1342. doi: 10.1002/lt.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kayler LK, Rasmussen CS, Dykstra DM, et al. Liver transplantation in children with metabolic disorders in the united states. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(3):334–339. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morioka D, Kasahara M, Takada Y, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for pediatric patients with inheritable metabolic disorders. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(11):2754–2763. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morioka D, Takada Y, Kasahara M, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for noncirrhotic inheritable metabolic liver diseases: Impact of the use of heterozygous donors. Transplantation. 2005;80(5):623–628. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000167995.46778.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakiya T, Sanada Y, Mizuta K, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15(4):390–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakiya T, Sanada Y, Urahashi T, et al. Living donor liver transplantation from an asymptomatic mother who was a carrier for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16(6):E196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2012.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cauley RP, Vakili K, Potanos K, et al. Deceased donor liver transplantation in infants and small children: Are partial grafts riskier than whole organs? Liver Transpl. 2013 doi: 10.1002/lt.23667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campeau PM, Pivalizza PJ, Miller G, et al. Early orthotopic liver transplantation in urea cycle defects: Follow up of a developmental outcome study. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100 (Suppl 1):S84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBride KL, Miller G, Carter S, Karpen S, Goss J, Lee B. Developmental outcomes with early orthotopic liver transplantation for infants with neonatal-onset urea cycle defects and a female patient with late-onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):e523–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darwish AA, McKiernan P, Chardot C. Paediatric liver transplantation for metabolic disorders. Part 1: Liver-based metabolic disorders without liver lesions. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35(3):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim IK, Niemi AK, Krueger C, et al. Liver transplantation for urea cycle disorders in pediatric patients: A single-center experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17(2):158–167. doi: 10.1111/petr.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazariegos GV, Morton DH, Sindhi R, et al. Liver transplantation for classical maple syrup urine disease: Long-term follow-up in 37 patients and comparative United Network for Organ Sharing experience. J Pediatr. 2012;160(1):116–21. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso EM, Ng VL, Anand R, et al. The SPLIT research agenda 2013. Pediatr Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1111/petr.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]