Abstract

Introduction:

Ocular trauma is a worldwide cause of visual morbidity, a significant proportion of which occurs in the industrial workplace and includes a spectrum of simple ocular surface foreign bodies, abrasions to devastating perforating injuries causing blindness. Being preventable is of social and medical concern.

Aim:

A prospective case series study, to know the profile of ocular trauma at a hospital caters exclusively to factory employees and their families, to co-relate their demographic and clinical profile and to identify the risk factors.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with ocular trauma who presented at ESIC Model hospital, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, from June 2010 to May 2011 were taken a detailed demographic data, nature and cause of injury, time interval between the time of injury and presentation along with any treatment received. Ocular evaluation including visual acuity, anterior and posterior segment findings, intra-ocular pressure and gonio-scopy in closed globe injuries, X-rays for intraocular foreign body, B-scan and CT scan were done. Data analyzed as per the ocular trauma classification group. The rehabilitation undertaken medically or surgically was analyzed. At follow-up, the final best corrected visual acuity was noted.

Results:

A total of 306 cases of ocular trauma were reported; predominantly in 20-40 year age group (72.2%) and in men (75%). The work place related cases were 50.7%and of these, fall of foreign bodies led the list. Visual prognosis was poorer in road traffic accidents rather than work place injuries owing to higher occurrence of open globe injuries and optic neuropathy. Finally, 11% of injured cases ended up with poor vision.

Conclusion:

Targeting groups most at risk, providing effective eye protection, and developing workplace safety cultures may together reduce occupational eye injuries.

Keywords: Eye injuries, occupational eye injury, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Ocular trauma is a worldwide cause of visual morbidity, a significant proportion of which occurs in the workplace and includes a spectrum of simple ocular surface foreign bodies (FBs)/minute corneal abrasions to devastating perforating injuries causing blindness.[1,2] The significance of the problem is compounded by the fact that most of these injuries are preventable, thus making it a social and medical concern. Management of ocular trauma and visual rehabilitation is different in different scenario.

Aim and objectives

To study: (1) The profile of ocular trauma at a hospital caters exclusively to factory employees and their relatives, particularly in garments and grinding factories. (2) To correlate the demographic and clinical profile and to identify the risk factors.

Design

A prospective case series study of ocular trauma was done from June 2010-May 2010.

Criteria

Patients of all ages and both genders with various levels of ocular injuries were included while severe local and systemic conditions which would alter the outcome of vision like infection, anemia, head injury, immune compromised status, with preexisting diseases like glaucoma, operated eyes (injury to previously operated eyes), proliferative vitreoretinopathy of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, Eales and so on were excluded.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 306 patients with ocular trauma, presented at eye outpatient department and emergency services in the ESIC Model Hospital, Rajajinagar, Bangalore, from June 2010 to May 2011 were included. Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained. A special protocol designed to note demographic data, nature and cause of injury, time interval between the time of injury, and presentation along with any treatment received were recorded. Ocular evaluation including visual acuity, anterior and posterior segment findings (lid or facial injury, subconjunctival hemorrhage or laceration, presence or absence of corneal/scleral perforation, hyphaema, iris injuries and afferent pupillary defect, presence or absence of vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment or foreign body, endophthalmitis, retinal breaks, choroidal rupture, and/or macular hole), intraocular pressure and gonioscopy in closed globe injuries were done. Results of X-rays for intraocular foreign body, B-scan and computed tomography scan if done were noted. Data analyzed and classified as per the ocular trauma classification group described by Pieramici et al.[3] The rehabilitation undertaken in the form of spectacles, contact lenses and/or intraocular surgeries was analyzed. At follow-up, the final best corrected visual acuity noted.

RESULTS

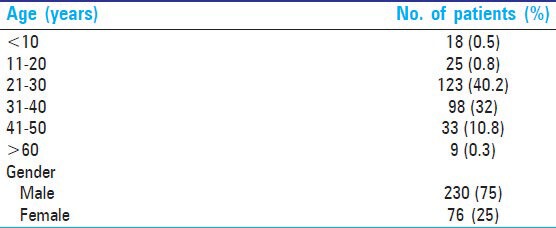

The results showed 72.2% of ocular trauma occurred in the age category of 21-40 years and 230 (75%) cases in men versus 76 (25%) were women [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution in ocular trauma

The analysis of place of injury showed that, 155 (50.7%) were work place related while 55 (18%) were at home, 50 (16.3%) were road traffic accidents (RTAs), 36 (11.8%) other accidental, 10 (3.3%) were due to assault as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Place of ocular trauma

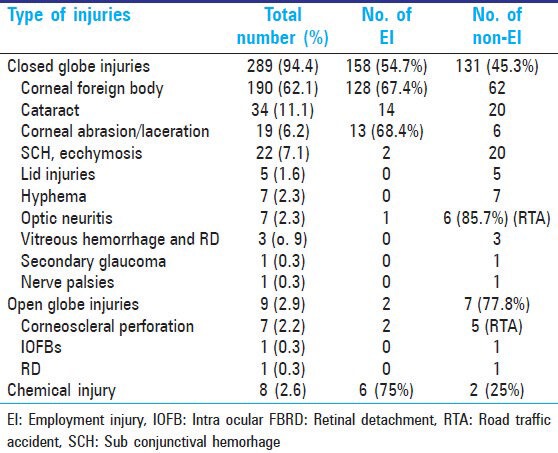

As per ocular trauma classification group,3 94.4% were closed globe injuries, while 2.9% were open globe injuries, and 2.6% were chemical injuries. The spectrum of ocular injuries (few examples shown in Figures 1–7) found in this study is shown in Table 3. Of the closed globe injuries, fall of FBs led this list occurring in 190 (62.1%) cases, followed by cataract in 34 (11.1%), lid and adnexal injuries in 27 (8.7%), corneal abrasions in 19 (6.2%), optic neuropathy in 7 (2.3%). Fall of FBs seen in 128 of 190 (67.4%) and corneal abrasions seen in 13 of 19 (68.4%) were due to employment injuries (EIs), while traumatic optic neuropathy seen in six of seven (85.7%) occurred due to non-EIs

Of nine open globe injuries, seven (77.8%) were due to RTA

Of chemical injuries, 6 (75%) occurred at work place and 2 (25%) in domestic place [Table 3].

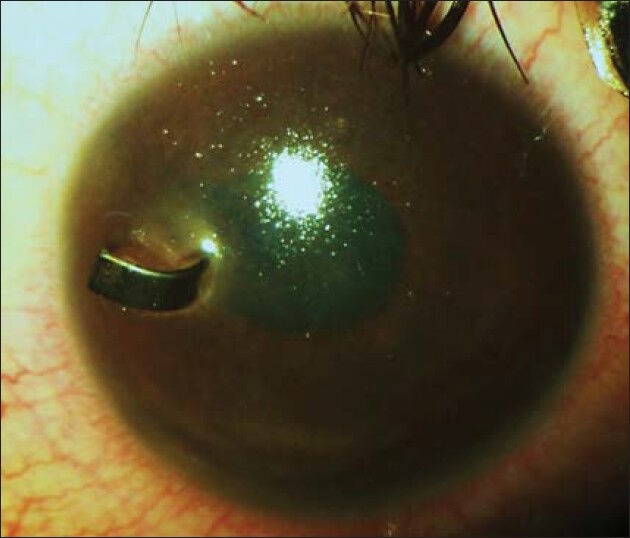

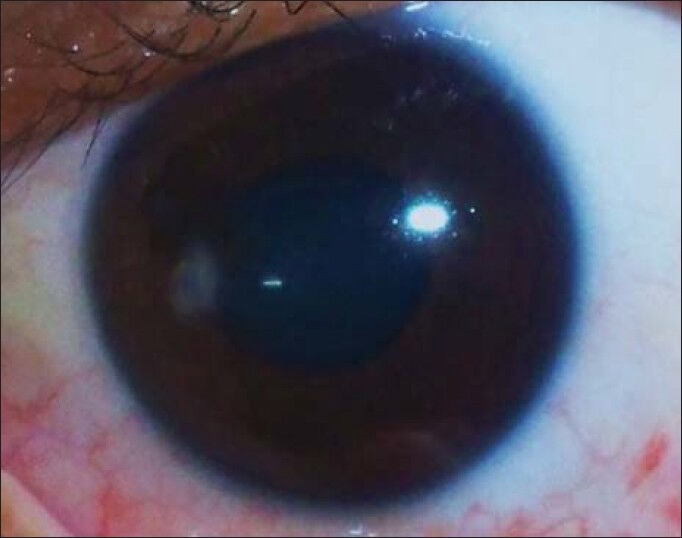

Figure 1.

Perforating foreign body (preoperative)

Figure 7.

Corneal foreign body

Table 3.

Spectrum of ocular trauma as per ocular trauma classification group

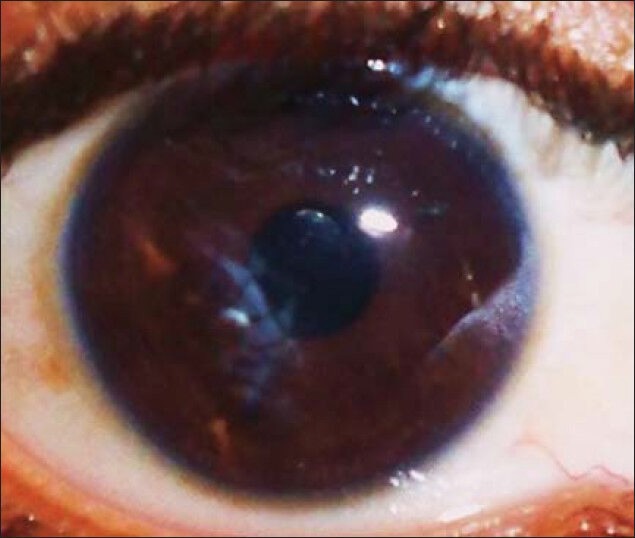

Figure 2.

Post removal of perforating foreign body

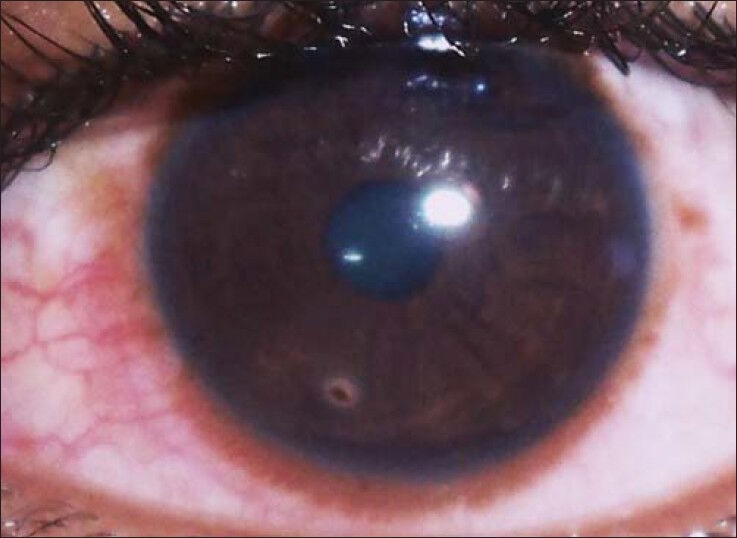

Figure 3.

Traumatic cataract with adherent leucoma (preoperative)

Figure 4.

Post cataract extraction with intra ocular lens implantation (postoperative)

Figure 5.

Chemical injury with epithelial defect at presentation

Figure 6.

Chemical injury with healing epithelial defect on treatment

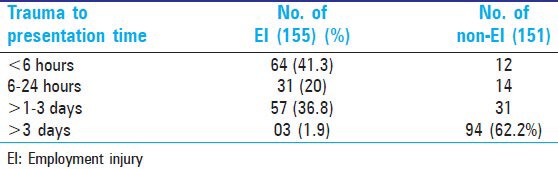

The time interval between trauma and patient presentation is shown in Table 4. The work place injuries presented within 3 days in 152 (98.1%) cases, while non-EI injuries presented beyond 3 days in 94 (62.2%).

Table 4.

Time interval between ocular trauma and presentation

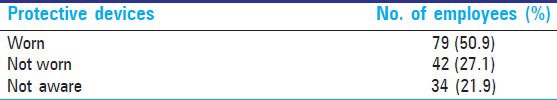

At work place, 79 (50.9%) were wearing protective glasses at the time injury, 42 (27.1%) were not wearing, and 34 (21.9%) were not aware of protective glasses [Table 5].

Table 5.

Ocular trauma and protective devices

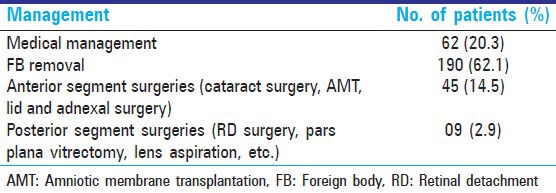

Medical line of treatment was the main stay in 252 (82.4%), anterior segment surgeries like cataract surgeries, amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT), lid and adnexal surgeries were done in 45 (14.5%), and posterior segment surgeries like pars plana vitrectomy, lens aspiration, RD surgeries, and so on were done in nine (2.9%) cases [Table 6].

Table 6.

Management of ocular trauma cases

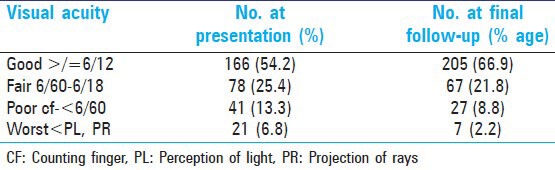

Final visual outcome from presentation to post treatment at available follow-up showed that 166 (54.2%) were in good vision (more than or equal to 6/12) in pretreatment phase, while it was 205 (66.9%) in post treatment phase and 62 (20.1%) cases who had poor vision (<6/60) in pretreatment phase were reduced to 34 (11%) with treatment as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Visual outcome in ocular trauma cases

DISCUSSION

Ocular trauma is an important cause of blindness and ocular morbidity. The common age for ocular trauma in this study was found to be 21-40 years (72.2%) and is similar to a prospective study by Shukla and Verma[4] involving 400 patients who showed that the commonest age group of people involved was in the third decade. A study done in Baluchistan by Qureshi[5] also showed similar age group involvement (21-30 years).

Men were affected in 75% in present study. Eye injuries remain a significant risk to worker health, especially among men in jobs requiring intensive manual labor. Many hospital- and population-based studies indicate a large preponderance (70-85%) of injuries affecting males.[6,7]

The present study having been done in a hospital catering exclusively to factory employees (manufacturing units like garments, grinding, and so on) and their families showed higher incidence of work place-related ocular trauma.

Of 306 cases, 155 (50.6%) were work place-related in present study. Work place injury ranged from 31% to 39% as per other studies.[8,9,10]

Closed globe injuries were 54.7% from work place in our study which is comparable to Karaman et al.,[11] study in his retrospective analyses of 383 patients in general population found 67.3% closed globe.

RTA cases reported with a delay due to involvement of other systems, while isolated ocular trauma cases at work place reported within 6 hours in 64 (41.3%). Ocular injuries are usually not given priority if it is accompanied with multiple system injuries. After identifying major organ injury and stabilizing the general condition of the patient, ocular injuries should be given preference to simple fractures, because visual loss can be a great morbidity if neglected for the patient once he recovers from the minor ailment.

The present study showed that only 51% were wearing protective glasses, while 27% were not wearing though, they were provided with and 22% were not aware of protective glasses. Ocular injuries at work are preventable and are attributable to the misuse or nonuse of protective eyewear.[12,13] Safety education has been highlighted by previous studies as they have reported worker noncompliance with personal protective equipment with up to half of workers not complying with health and safety regulations.[1,14] To meet these requirements and to reduce accidents, many larger companies in the construction industry use the Construction Skills Certificate Scheme to improve education and certify awareness of these issues.

Though, visual outcome did improve after medical and/or surgical management, still 11% were left with poor vision. The physical disability adds to the social, emotional, and psychological impact on the overall development of an individual.

CONCLUSION

Employees need to be emphasized on work safety cultures, proper training, and use of protective equipments.

Clinicians should be referring the patients as early as possible for eye care after stabilizing general conditions or else it would be too late to restore the potential vision.

Hence, we conclude that, targeting groups most at risk, increasing worker training, providing effective eye protection, and developing workplace safety cultures may together reduce occupational eye injuries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai P, MacEwen CJ, Baines P, Minassian DC. Incidence of cases of ocular trauma admitted to hospital and incidence of blinding outcome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:592–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.7.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ngo CS, Leo SW. Industrial accident-related ocular emergencies in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:280–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieramici DJ, Sternberg P, Jr, Aaberg TM, Sr, Bridges WZ, Jr, Capone A, Jr, Cardillo JA, et al. A system for classifying mechanical injuries of the eye (globe). The Ocular Trauma Classification Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:820–31. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shukla IM, Verma RN. A clinical study of ocular injuries. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1979;27:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qureshi MB. Ocular injury pattern in Turbat, Baluchistan, and Pakistan. Community Eye Health J. 1997;10:57–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schein OD, Hibberd PL, Shingleton BJ, Kunzweiler T, Frambach DA, Seddon JM, et al. The spectrum and burden of ocular injury. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:300–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz J, Tielsch JM. Lifetime prevalence of ocular injuries from the baltimore eye survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1564–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090110130038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jovanovic M, Stefanovic I. Mechanical injuries of the eye: Incidence, structure and possiblilities for prevention. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;67:983–90. doi: 10.2298/vsp1012983j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gyasuddin S. Ocular injuries in a mountainous, rural area of Gizan, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 1993;7:106–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson GJ, Mollan SP. Occupational eye injuries: A continuing problem. Occup Med. 2009;59:123–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karaman K, Gverovic-Antunica A, Rogosic V, Lakos-Krzelj V, Rozga A, Radocaj-Perko S. Epidemiology of adult eye injuries in Split-Dalmatian country. Croat Med J. 2004;45:304–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macewen CJ. Eye injuries: A prospective survey of 5671 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:888–94. doi: 10.1136/bjo.73.11.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loncarek K, Brajac I, Filipovic T, Caljkusic-Mance T, Stalekar H. Cost of treating preventable minor ocular injuries in Rijeka, Croatia. Croat Med J. 2004;45:314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngo CS, Leo SW. Industrial accident-related ocular emergencies in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:280–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]