Abstract

Trichotillomania (TTM) is a type of impulse control disorder, characterized by recurrent pulling of hair. The etiology of TTM is complex, but a genetic contribution to this condition was advocated based on a limited number of reports on familial TTM. We report a 13-year-old male with history of focal hair loss in the scalp. Examination showed a patchy area of hair loss, with several short broken hairs of varying lengths. Dermoscopy and pathology examinations were consistent with TTM. Upon further questioning, his father admitted repeated pulling of his beard. The paternal grandfather also suffers from severe hair pulling of his beard since puberty. To our knowledge, this is the first report of TTM in a 3 generation family. This report strengthens the possibility that TTM is a genetic disease, probably with a complex inheritance pattern. It also highlights the importance of appropriate family history taking when examining a TTM patient.

Keywords: Family, genetics, trichotillomania

INTRODUCTION

Trichotillomania (TTM) is a type of impulse control disorder, characterized by recurrent pulling of hair, which leads to pleasure and relief of tension.[1,2] Prevalence rates of this condition range between 1% and 13.3%, with initial mean age of onset between 10 years and 13 years[3] and a notable peak at 12-13. The disease leads to hair loss, which may sometimes be severe and lead to significant social and functional impairment.[4] The etiology of the disease is still unknown, although some have suggested a genetic component. This was based on a limited number of reports on familial hair pulling[1] and one twin concordance study.[5] We hereby describe a case of familial TTM in three generations, thereby underlining the familial basis for this disorder.

CASE REPORT

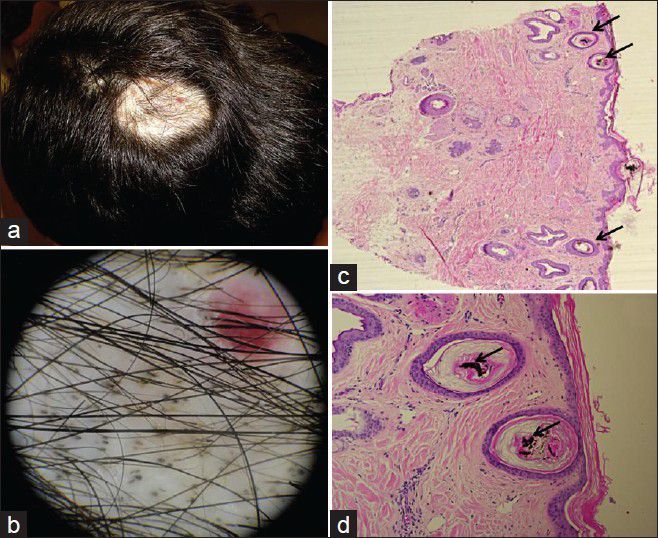

A 13-year-old male presented with 1-year history of focal hair loss in the mid-frontal scalp. He was previously treated with local steroids for presumed alopecia areata, with no improvement. Examination revealed a patchy area of hair loss, with several short broken hairs of varying lengths [Figure 1a]. On dermoscopy examination of the scalp, we found the typical features of TTM, including short hairs with trichoptilosis, broken hair (different lengths) and black dots [Figure 1b]. Additionally, traumatic bleeding was evident. Histological examination showed trichomalacia with irregularly shaped hair follicles and melanin pigment casts [Figure 1c and d]. Upon further questioning, the father admitted repeated pulling of his beard hairs since puberty, with mild-to-moderate severity of symptoms. The 60-year-old paternal grandfather also suffers from severe recurrent hair pulling of his beard since puberty, which sometimes precludes him from leaving home.

Figure 1.

(a) Patchy area of hair loss on the scalp, with several short broken hairs of varying lengths; (b) Dermoscopy of the scalp lesion demonstrating short hairs with trichoptilosis, broken hair (different lengths) and black dots; (c-d) Low (c) and high (d) magnification histopathology of the scalp lesion demonstrating the presence of trichomalacia with irregularly shaped hair follicles (arrows, c) and melanin pigment casts (arrows, d)

DISCUSSION

It is believed that the etiology of TTM is complex, involving biological, psychological and social factors.[6] Nevertheless, a genetic contribution to this condition was strongly advocated. This was based on a limited number of reports on familial TTM[1] and one twin concordance study.[5] In this twin study, respective concordance rates for monozygotic and dizygotic twin pairs were 38.1% and 0% for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV criteria and 58.3% and 20% for non-cosmetic hair-pulling, leading to a heritability estimate of 76.2%.[5] Indeed, several gene candidates were suggested as contributing to disease development. Rare variations in SLITRK1 were associated with disorders of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum and among them also TTM.[7,8] Mouse models also suggested a relationship between mutations in Hoxb8 and Sapap3 and TTM-like behavior in mice.[9,10] Nevertheless, the genetics of TTM are complex and still not well understood.[1]

Although several cases of familial TTM have been reported, to our knowledge, this is the first report of TTM in a three-generation family. This report strengthens the possibility that TTM is a genetic disease, probably with a complex inheritance pattern.

It also underlines the importance of proper family history taking when examining a TTM patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chattopadhyay K. The genetic factors influencing the development of trichotillomania. J Genet. 2012;91:259–62. doi: 10.1007/s12041-011-0094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christenson GA, Crow SJ. The characterization and treatment of trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 8):42–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong JW, Nguyen TV, Koo JY. Primary psychiatric conditions: Dermatitis artefacta, trichotillomania and neurotic excoriations. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:44–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.105287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison JP, Franklin ME. Pediatric trichotillomania. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:188–96. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0269-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak CE, Keuthen NJ, Stewart SE, Pauls DL. A twin concordance study of trichotillomania. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:944–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: A current review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:181–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abelson JF, Kwan KY, O’Roak BJ, Baek DY, Stillman AA, Morgan TM, et al. Sequence variants in SLITRK1 are associated with Tourette's syndrome. Science. 2005;310:317–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1116502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuchner S, Cuccaro ML, Tran-Viet KN, Cope H, Krishnan RR, Pericak-Vance MA, et al. SLITRK1 mutations in trichotillomania. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:887–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greer JM, Capecchi MR. Hoxb8 is required for normal grooming behavior in mice. Neuron. 2002;33:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch JM, Lu J, Rodriguiz RM, Trotta NC, Peca J, Ding JD, et al. Cortico-striatal synaptic defects and OCD-like behaviours in Sapap3-mutant mice. Nature. 2007;448:894–900. doi: 10.1038/nature06104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]