Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulate gene expression at post-transcriptional level and are key modulators of immune system, whose dysfunction contributes to the progression of neuroinflammatory diseaseas such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the most widespread motor neuron disorder. ALS is a non-cell-autonomous disease targeting motor neurons and neighboring glia, with microgliosis directly contributing to neurodegeneration. As limited information exists on miRNAs dysregulations in ALS, we examined this topic in primary microglia from superoxide dismutase 1-G93A mouse model. We compared miRNAs transcriptional profiling of non-transgenic and ALS microglia in resting conditions and after inflammatory activation by P2X7 receptor agonist. We identified upregulation of selected immune-enriched miRNAs, recognizing miR-22, miR-155, miR-125b and miR-146b among the most highly modulated. We proved that miR-365 and miR-125b interfere, respectively, with the interleukin-6 and STAT3 pathway determining increased tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) transcription. As TNFα directly upregulated miR-125b, and inhibitors of miR-365/miR-125b reduced TNFα transcription, we recognized the induction of miR-365 and miR-125b as a vicious gateway culminating in abnormal TNFα release. These results strengthen the impact of miRNAs in modulating inflammatory genes linked to ALS and identify specific miRNAs as pathogenetic mechanisms in the disease.

Keywords: ALS, microglia, microRNAs, P2X7 receptor, TNFalpha

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a widespread motor neuron disorder causing injury and death of lower and upper motor neurons.1 Identification of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) mutations accounting for about 20% of familiar ALS2 allowed the production of transgenic mice overexpressing mutated SOD1 genes, with the SOD1-G93A strain being the most exploited. These mice develop loss of motor neurons together with symptoms resembling human ALS.3 Moreover, clinical and electrophysiological data show that human SOD1-G93A phenotype resembles sporadic ALS in terms of disease progression, thus identifying the SOD1-G93A model as appropriate to investigate the molecular mechanisms of the sporadic disease.4

Mutated SOD1-mediated toxicity derives from both motor neurons and neighboring glia, with microgliosis highly contributing to neurodegeneration,5, 6, 7, 8 although far little attention has been paid to the study of how mutated SOD1 affects microglia features in particular.9, 10 Multiple mechanisms control the proper levels of protein expression during inflammation and, among these, microRNAs (miRNAs).11 These small, non-coding RNAs are important regulators of protein synthesis under rapid environmental changes such as receptor activation.12 Apart from their recognized role in cellular specification and physiopathological mechanisms, the recent discovery of circulating miRNAs also suggests that they provide novel means for paracrine and systemic communication.13, 14 Current findings demonstrate a correlation between miRNAs expression and microglia activation.15 For instance, mutations of TDP43, a gene involved in miRNAs biogenesis, were lately found correlated to ALS.16 Moreover, dysregulation of miRNAs in the best model for miRNAs ablation, the Dicer knockout mice, causes spinal motor neuron disease.17 Finally, lack of miR-206 accelerates disease progression in ALS mouse.18 All these findings strenghten the role of miRNAs in ALS pathology.

Microglia activation can occurr through different means, among wich released tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and extracellular ATP binding to ionotropic purinergic P2X7r.19 In CNS, P2X7r is abuntantly expressed in microglia and involved in various pathologies.20 In ALS, P2X7r is found upregulated in microglia of human spinal cord and in sections from mutated SOD1 rats.21, 22 In a previous work, we showed that ALS microglia exhibit P2X7r-dependent enhancement of TNFα, COX-2, CD68, iNOS, NOX and pERK proteins, together with toxic effects exerted on neuronal cells.23, 24 However, despite a hypothesized role of P2X7r in ALS pathology, the full signaling and pathways involved are still unknown.

The aim of this work was to define the miRNAs' signature of microglia from non-transgenic (nt) and SOD1-G93A mice in both resting and P2X7r-activated conditions. We detected a specific subset of dysregulated inflammatory miRNAs that might contribute to ALS alterations. Our results strengthen the impact that miRNAs might have on post-transcriptional modulation of genes linked to inflammation and particularly to ALS.

Results

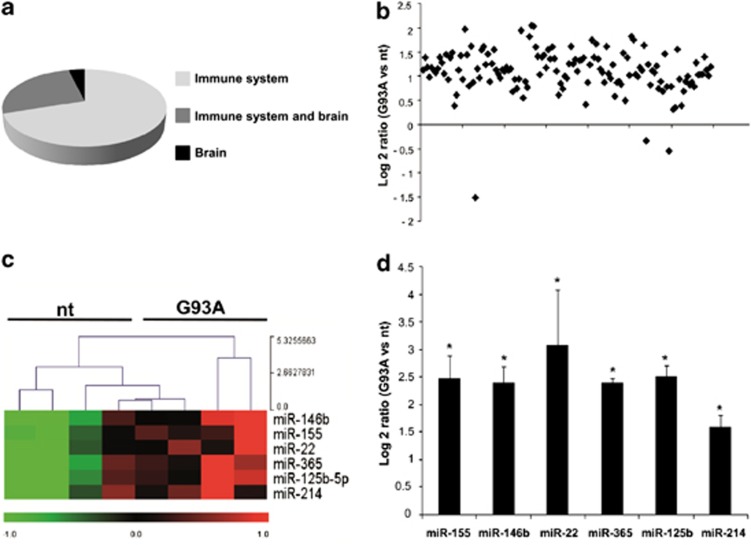

Profiling of miRNA transcriptome of brain microglia from nt and SOD1-G93A mice

To examine the transcriptional profile and downstream regulation of individual miRNAs likely relevant to the ALS SOD1-G93A microglia phenotype, as appropriate model system we adopted primary microglia purified from newborn cerebral cortex of nt and SOD1-G93A mice. Of the total 627 mouse miRNAs included on the microarray chip employed, only a subset of about 130 miRNAs showed significant hybridization signal and this occurred in both nt and ALS microglia. We defined this novel subset as the miRNAs transcriptome of the brain microglia. As microglia share properties with both immune and nervous system cells (being the immune-competent cells of the brain), we compared the microglia miRNA transcriptome with the complete mouse miRNA profile of Landgraf et al.25 (Supplementary Figure 1). The majority of miRNAs that we found significantly expressed in the brain microglia cultures were also present in the whole immune system and brain.25 Of these,∼60% were immune system enriched,∼35% were shared by immune system and brain transcriptome, only∼5% belonged exclusively to the brain (Figure 1a). The transcriptional profile of the miRNA transcriptome of the brain microglia was then tested for differential expression in nt and ALS microglia. We found that the overexpression of human SOD1-G93A transgene increased the overall transcriptional profile of microglia (Figure 1b), with 78 different miRNAs being significantly upregulated (listed in Supplementary Figure 1C). We then adopted two selection criteria for further validation and investigation: (1) statistical significance; (2) well-known implication in immune system regulation. By this way, we came up with six promising candidates (miR-155, miR-146b, miR-22, miR-365, miR-125b and miR-214) that were confirmed to be upregulated by quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR (QPCR) (Figure 1c), in line with the microarray results (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

MiRNA profiling of microglia from nt and SOD1-G93A mice. (a) Immune system and brain-related miRNAs expressed in microglia on the basis of Landgraf et al.25 (b) Overall statistics of down- and upregulated miRNA genes in SOD1-G93A microglia. Log2 ratios (SOD1-G93A/nt) are shown. Only miRNAs with a mean expression value >20.0 in linear scale were selected in order to avoid values too close to noise level. (c) Heat maps of six differentially expressed miRNAs in nt and SOD-G93A microglia. Red to green indicates high to low expression (P≤0.05). (d) QPCR validation of the miRNA microarray data of the six differentially expressed miRNAs represented as log2 ΔΔCT

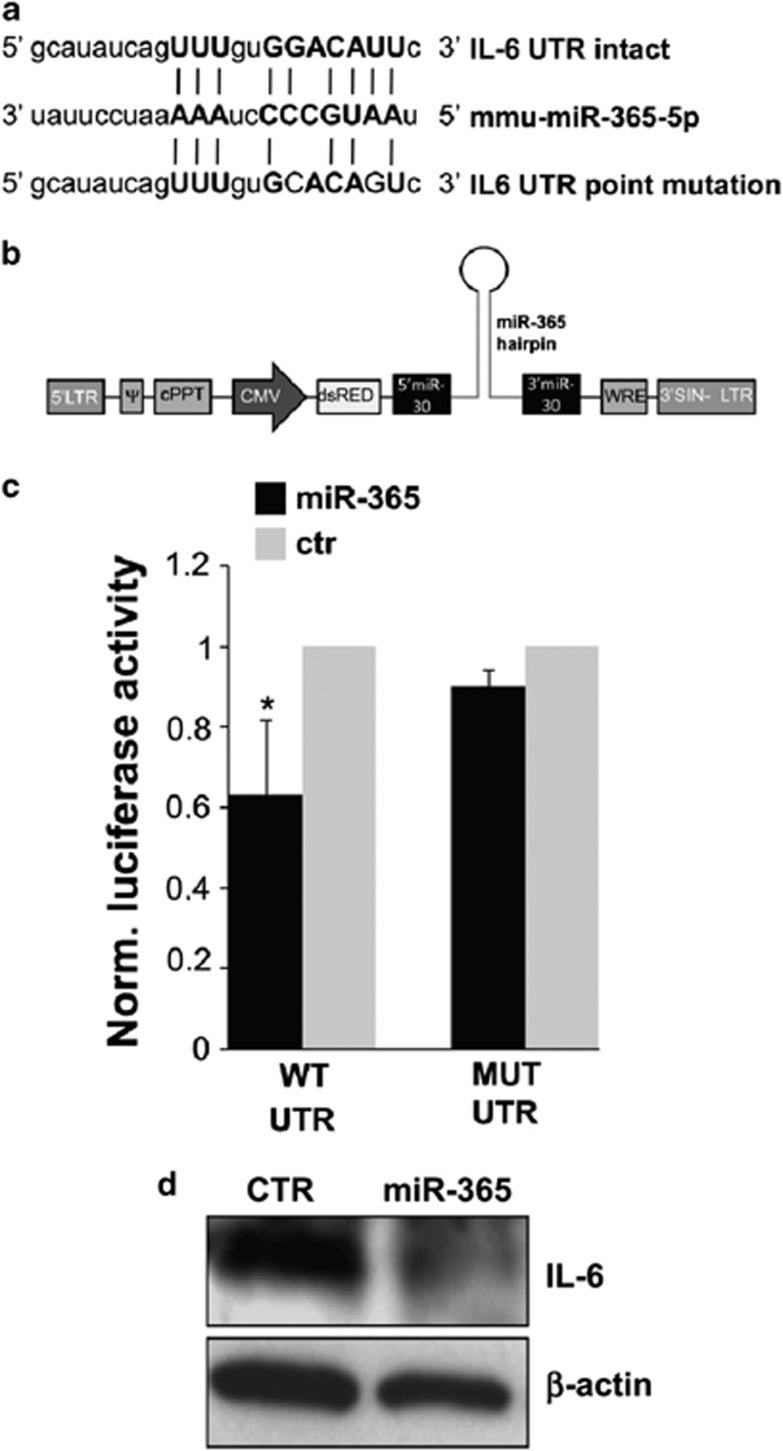

IL-6-negative regulation by miR-365 in ALS microglia

The putative binding site of miR-365 to the interleukin (IL)-6 3′-untraslated region (UTR) is broadly, although not strictly, conserved among vertebrates and was previously validated only in human.26 As miRNA/mRNA interactions are very stringently dependent on sequence composition, we first validated by in vitro assay whether mmu-miR-365 binds to the 3′-UTR of mouse IL-6 causing translational inhibition. We constructed two plasmids encoding a renilla luciferase transcript with either wild-type or mutant IL-6 3′-UTR (Figure 2a), which were co-transfected with a miR-30-based lentiviral vector driving mature miR-365 overexpression (Figure 2b). We found that miR-365 inhibited the expression of the transcript containing wild-type IL-6 3′-UTR but not mutant IL-6 3′-UTR (Figure 2c), thus demonstrating a specific inhibitory effect of miR-365 on IL-6 3′-UTR, through direct interaction.

Figure 2.

Validation of mouse IL-6 as direct miR-365 target. (a) Alignment of miR-365 and its target sites in intact or mutated IL-6 3′-UTR. (b) Schematic representation of pprime-dsRed-miR-365 construct. (c) Normalized luciferase activities of IL-6 3′-UTR renilla luciferase reporter plasmid, and IL-6 3′-UTR-mutant renilla luciferase reporter plasmid, 48 h after co-transfection together with pprime-miR-365 or empty vector in HEK293 cells. (d) Western blotting with anti-IL-6 antibody of total lysates from empty vector and pprime-miR-365-infected microglial cells, at 96 hours post virus transduction. β-actin was used for protein normalization

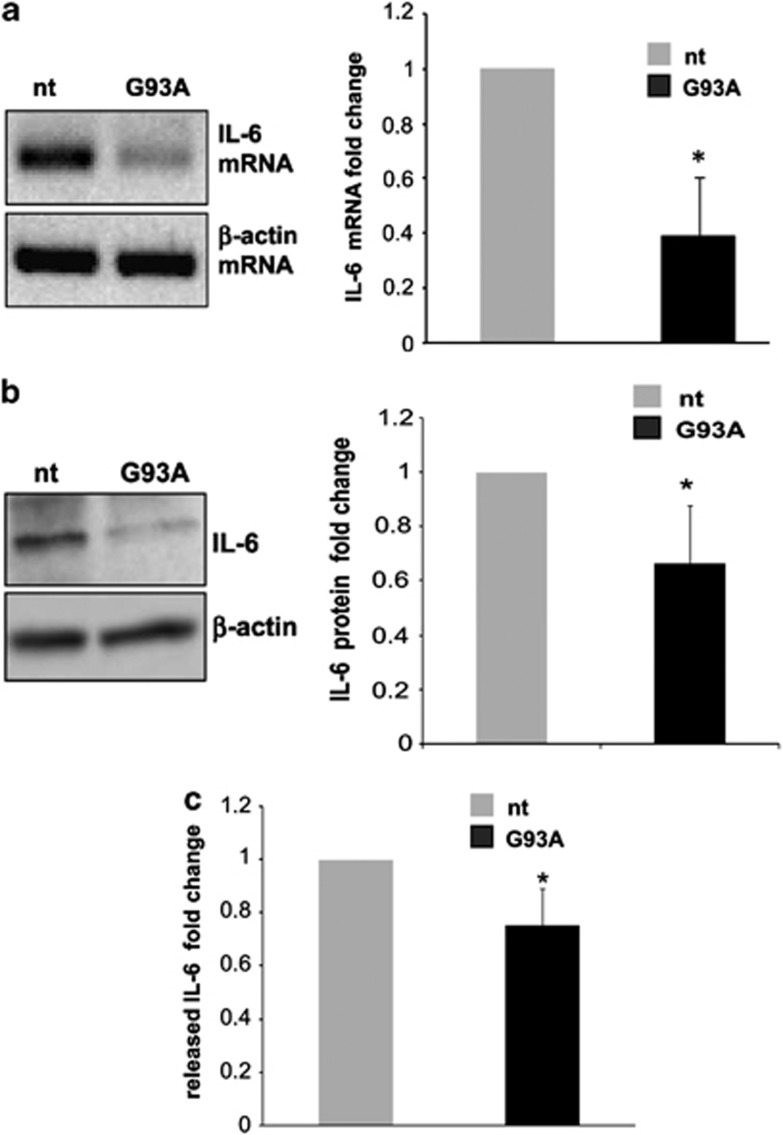

As target regulation by miRNAs is under the influence of the specific intracellular milieu of each cell type, in vitro miRNA/mRNA interactions had to be necessarily validated in our microglia culture system. In order to prove miR-365 as a negative regulator of IL-6 in microglia, we overexpressed the mature sequence of miR-365 by lentiviral transduction. Western blot analysis of IL-6 protein performed at 96 h post transduction showed that exogenous miR-365 repressed IL-6 production in microglia (Figure 2d). Given that IL-6 was found to be a target of miR-365 (Figures 2c and d), and that miR-365 was found augmented in ALS (Figures 1c and d), we directly measured the content of IL-6 in ALS microglia, by semiquantitative RT-PCR, western blotting and ELISA. A significant reduction of IL-6 occurred at both mRNA, total and secreted protein levels in SOD1-G93A microglia (Figures 3a–c), thus establishing a novel inverse correlation between IL-6 and miR-365 levels.

Figure 3.

IL-6 downregulation in SOD1-G93A mouse microglia. (a) Semiquantitative RT-PCR using specific primers for IL-6 and β-actin mRNAs, on total RNA from nt and SOD1-G93A microglia. β-actin was used for normalization. (b) Western blotting with anti-IL-6 antibody on total lysates from nt and SOD1-G93A microglia. β-actin was used for protein normalization. (c) IL-6 levels in the culture media of microglia from nt and G93A mice, after 6 h incubation in fresh media, as assessed by ELISA

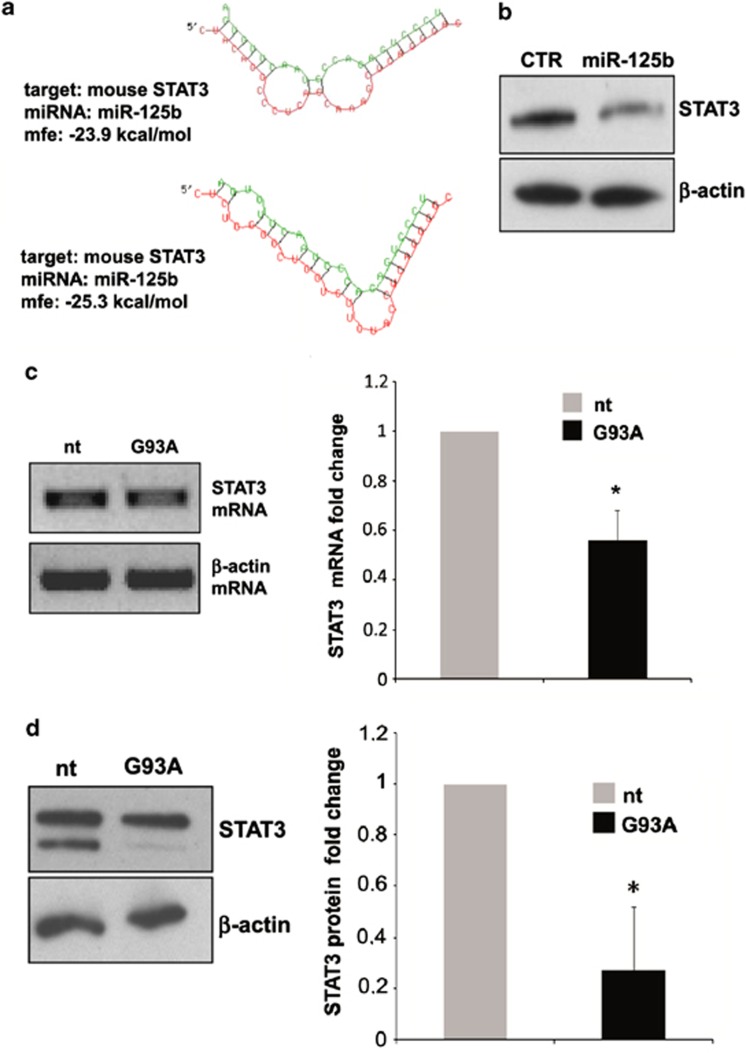

STAT3-negative regulation by miR-125b in ALS microglia

STAT3 is the major downstream effector of IL-6 in murine brain27 and mouse STAT3 3′-UTR contains two conserved binding sites for miR-125b, which we found upregulated in ALS microglia (Figures 1c and d). Predictive hybridization between miR-125b and STAT3 3′-UTR by RNA hybrid28 shows very low minimum free energy with two binding sites (Figure 4a), suggesting STAT3 as a candidate target of miR-125b. Moreover, STAT3 3′-UTR is a validated target of miR-125b in vitro and in a mouse granulocytic cell line.29 With the necessity to prove this same interaction in microglia, we transduced nt cells with a lentiviral system driving the overexpression of mature miR-125b and performed western blot analysis at 96 h post transduction. We demonstrated that exogenous miR-125b reduces STAT3 protein (Figure 4b). Having demonstrated that STAT3 is a target of miR-125b (Figure 4b), and that miR-125b is increased in ALS (Figures 1c and d), we then directly measured the content of STAT3 in ALS microglia, by semiquantitative RT-PCR and western blotting. The reduction of STAT3 that we demonstrated in SOD1-G93A microglia at both mRNA and total protein levels (Figures 4c and d) thus underlines a novel inverse correlation between STAT3 and miR-125b levels.

Figure 4.

MiR-125b-mediated STAT3 downregulation in SOD1-G93A mouse microglia. (a) The two minimum free energy duplexes of miR-125b-5p and 3′-UTR of mouse STAT3 (NM_011486.4) as predicted by RNA hybrid. (b) Western blotting with anti-STAT3 antibody of total lysates from empty vector and pprime-miR-125b infected microglia at 96 hours post virus transduction. β-actin was used for protein normalization. (c) Semiquantitative RT-PCR using specific primers for STAT3 and β-actin mRNAs of total RNA from nt and SOD1-G93A microglia. β-actin was used for normalization. (d) Western blotting with anti-STAT3 antibody of total lysates from nt and SOD1-G93A microglia. β-actin was used for protein normalization

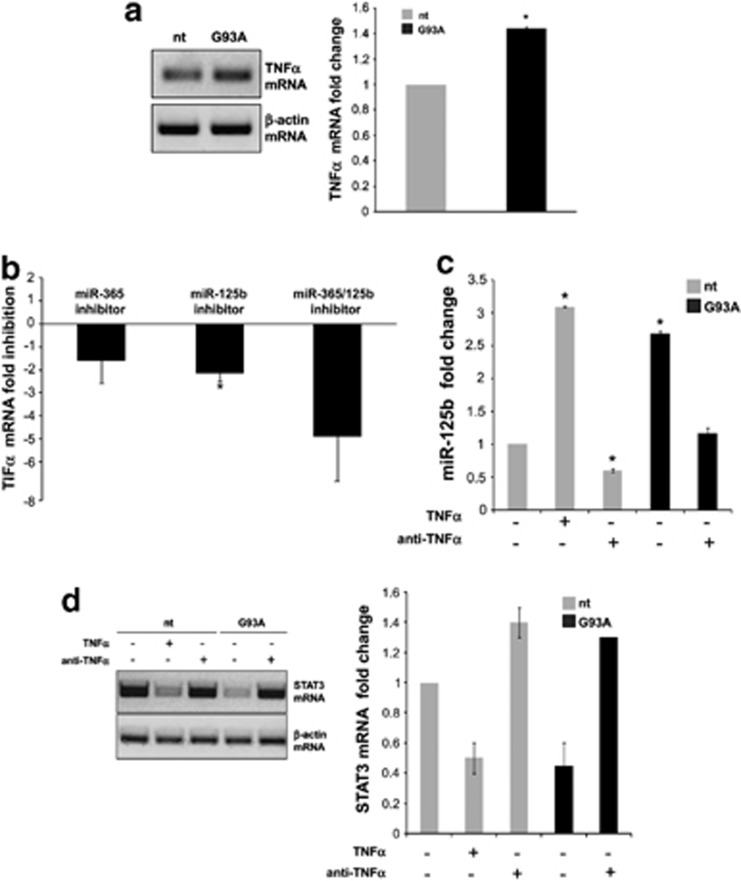

TNFα regulation by miR-365 and miR-125b

Elevated production of TNFα is a common feature of several inflammatory diseases including ALS. We demonstrated here that TNFα mRNA increases about 40% in SOD1-G93A microglia (Figure 5a), thus confirming previous data on protein level.23 As the IL-6/STAT3 pathway is known to downregulate TNFα synthesis30 only in monocytes after LPS stimulation and similar data are not available in microglial cells, in order to validate the hypothesis that miR-365 and miR-125b regulate TNFα through the IL-6/STAT3 pathway, we transfected SOD1-G93A microglia with specific miR-365/miR-125b inhibitors and demonstrated an approximately fivefold downregulation of TNFα mRNA by QPCR (Figure 5b). Most importantly, the single transfection of miR-125b inhibitor directly targeting STAT3 3′-UTR, was able per se to produce a significant inhibition of TNFα mRNA (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

TNFα-mediated miR-125b upregulation and STAT3 repression in microglia. (a) Semiquantitative RT-PCR performed using specific primers for mouse TNFα and β-actin mRNAs on nt and SOD1-G93A microglia total RNA. β-actin was used for normalization. (b) QPCR quantification of TNFα mRNA was performed at 48 h after transfection with the specified miRNA inhibitors. (c) QPCR quantification of miR-125b and (d) semiquantitative RT-PCR of STAT3 mRNA in nt and SOD1-G93A microglia upon 24 h of TNFα (10 ng/ml) or anti-TNFα (0.5 ng/ml) treatment

TNFα regulation of STAT3 via miR-125b in microglia

TNFα is known to regulate miR-125b expression in monocytes and in a macrophage cell line after LPS stimulation,31, 32 whereas this mechanism is not yet proven in microglia. We thus investigated whether exogenous TNFα could directly control miR-125b production in ALS microglia. We stimulated nt cells with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 24 h and by QPCR we found that miR-125b was overexpressed to levels comparable to ALS microglia (Figure 5c). The treatment with anti-TNFα moreover restored miR-125b to basal levels in SOD1-G93A microglia and even more in nt cells. To further prove that STAT3 is a target of miR-125b, we performed semiquantitative RT-PCR on STAT3 mRNA of nt and SOD1-G93A microglia exposed to TNFα or anti-TNFα treatments. We demonstrated a previously unknown TNFα-dependent inverse correlation occurring between miR-125b and STAT3 (Figure 5d).

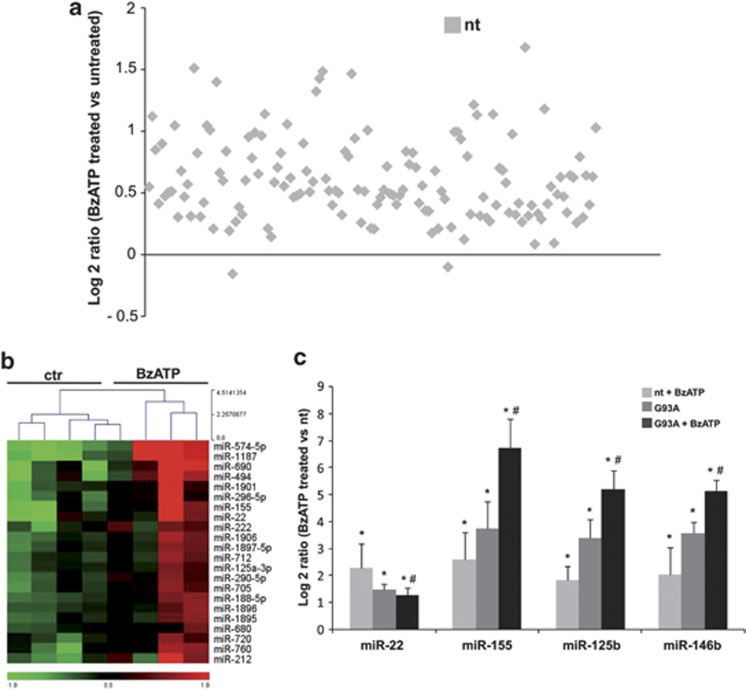

P2X7r-driven miRNA expression profile of brain microglia from wild-type mice

To identify those miRNAs whose expression is regulated by activation of microglia for instance through P2X7r, a miRNA microarray analysis was carried out using RNA isolated from nt and SOD1-G93A microglia upon 2 h from activation with the P2X7r agonist 2′(3′)-O-(4-Benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate (BzATP, 100 μM). As one of the recognized effects of BzATP on ALS microglia is the induction of TNFα content,23 we evaluated the miRNA expression profile in microglia at the peak of BzATP-mediated TNFα mRNA induction. This occurred at 2 h, in both nt and SOD1-G93A microglia (Supplementary Figure 2). Under these conditions, most of microglia-expressed miRNAs were found upregulated in nt cells (Figure 6a), thus showing a similar effect to that obtained by overexpression of SOD1-G93A in microglia. Among the P2X7r-induced miRNAs, 22 resulted more significantly upregulated (Figure 6b) and miR-155, miR-22 upregulation was then confirmed by both microarray and QPCR (Figure 6c). Induction of miR-146b and miR-125b was instead proved to be statistically significant only by QPCR analysis (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

P2X7r-mediated miRNAs regulation in nt and ALS microglia. (a) Overall statistics of down- and upregulated miRNA genes in BzATP-treated nt microglia. Log2 ratios (BzATP-treated nt/untreated nt) are shown. (b) Heat maps of 22 differentially expressed miRNAs in BzATP-treated nt microglia. Red to green indicates high to low expression (P≤0.05). (c) QPCR data of four differentially expressed miRNAs in BzATP-treated and untreated nt and SOD1-G93A microglia. Data are expressed as log2 ΔΔCT with respect to untreated nt. *P≤0.05 with respect to untreated nt; #P≤0.05 with respect to BzATP-treated nt

P2X7r-driven miRNAs regulation in microglia from ALS mice

As previous results from our lab23, 24 demonstrated that the inflammatory effect of BzATP in microglia is enhanced in SOD1-G93A when compared with nt cells, we investigated this effect also regarding miRNAs expression. QPCR was performed to assess the levels of miR-125b, miR-146b, miR-155, and miR-22 in SOD1-G93A microglia upon 2 h of treatment with 100 M BzATP. Also in this case, we observed an increase of miR-125b, in addition to miR-146b and miR-155 in both nt and ALS microglia (Figure 6c). Surprisingly, miR-22 expression was significantly downregulated only in SOD1-G93A microglia upon BzATP treatment.

Discussion

The responses of brain-resident macrophages, microglia, rely on dynamic, specific and tightly regulated gene expression changes ensuring the exact quality and quantity of inflammatory mediators in a time-dependent manner. Dysregulation of this system, leading to uncontrolled immune cell activation, is associated with progression of neurodegenerative diseases.33 A prominent part in orchestrating microglia activation is reserved to protein transcription factors that induce a battery of genes responsible for switching on/off the inflammatory action. However, transcriptional regulation fails to explain all the complex timing and cell specificity of gene expression, thus suggesting the existence of additional layers of molecular control. MiRNAs operating as fine tuners of post-transcriptional events mediate neuronal gene expression34 and are presently emerging as key factors also in microglia reactivity.15 As a consequence, miRNA dysregulation becomes instrumental for understanding many neuroinflammatory diseases, including ALS.35 In the present study, we examined the role of miRNAs in brain microglia from healthy mouse and carried out a comparative analysis with the SOD1-G93A ALS microglia. We performed miRNAs expression profiling by using the standardized microarray approach that is considered the most accurate to this purpose.36 We established that brain microglia maintain their immune system signature despite their brain location, as shown by the expression of mostly immune-enriched miRNAs. This corroborates the similarity between microglia and circulating macrophages previously shown by mRNA profiling.37 In addition, we found that overexpressed mutated SOD1 is able per se to significantly upregulate a huge proportion of the brain-resident microglia miRNAs. Our findings in brain microglia further extend those reported by Butovsky et al.38 using CD39-selected microglia from spinal cord and corroborate the importance of miRNAs dysregulation in SOD1-G93A ALS microglia. Despite the intrinsic CNS site-specific difference of microglia,39 several miRNAs such as miR-146b, miR-29b, let-7a/b, miR-27b, miR-21, miR-210 and miR-155 were similarly found upregulated. Among those miRNAs that we validated, miR-125b, miR-146b and miR-155 are typical components of the innate immune system,40 with mir-125b overexpression being also responsible for direct macrophage activation.41 Moreover, upregulation of miR-125b causing neuroinflammatory detrimental downregulation of the immune system repressor CFH42 was also demonstrated in Alzheimer's disease brain tissue, as well as in primary neuronal-glial cells during ROS-generating oxidative stress.43 For this reason, we hypothesized that miR-125b overexpression might represent a cross-road among different neuroinflammatory conditions. As both Alzheimer's disease44 and ALS45, 46 share the pathological activation of cytokine-mediated nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling, and miR-146, miR-155, miR-214 and miR-365 all converge in NFκB-mediated immune cell regulation,26, 47 it will be interesting to verify whether dysregulation of these specific miRNAs might be instrumental to abnormal NF-κB activation in ALS.

Although neuroinflammation is a fundamental component of ALS progression, with microglia having a key causative role in the process, whether the expression of inflammatory cytokine pathway is directly regulated by miRNAs in ALS microglia has not been previously determined.

A pathological hallmark characterizing ALS is an abnormal production and release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6.48, 49, 50 Although studies performed on total extract of mouse spinal cord found that both IL-6 and TNFα levels are increased in SOD1-G93A model,51, 52 IL-6 results instead downregulated in isolated spinal cord microglia from asymptomatic phase to end stage of the disease,48 suggesting that the release of IL-6 in vivo is not cell autonomous. Consistently with these last findings, we demonstrated a significant IL-6 downregulation in ALS brain microglia cultures.

Being known that IL-6 is a validated target of miR-365 only in human system,26 with our work we demonstrated that miR-365/IL-6 interaction is conserved also in mouse, despite a single mismatch in the seed region. The presence of functional noncanonical sites with a single mismatch in the seed region is for instance reported also in the majority of miR-155 targets.53 In support of the miR-365/IL-6 targeting, we next demonstrated that IL-6 protein content is inhibited by exogenous miR-365 in primary microglia. As we also proved here that IL-6 mRNA and protein are constitutively downregulated in ALS microglia, we established for the first time that upregulation of miR-365 is at least in part responsible for IL-6 dysregulation in ALS.

STAT3 is known to be the first downstream effector of IL-6 and, moreover, a validated target of miR-125b in both human54 and mouse.29 Here we demonstrated that also STAT3 total protein is decreased in primary microglia in the presence of exogenous miR-125b. Moreover, we found that STAT3 mRNA and total protein are decreased in ALS microglia, suggesting that STAT3 downregulation is directly controlled by miR-125b overexpression.

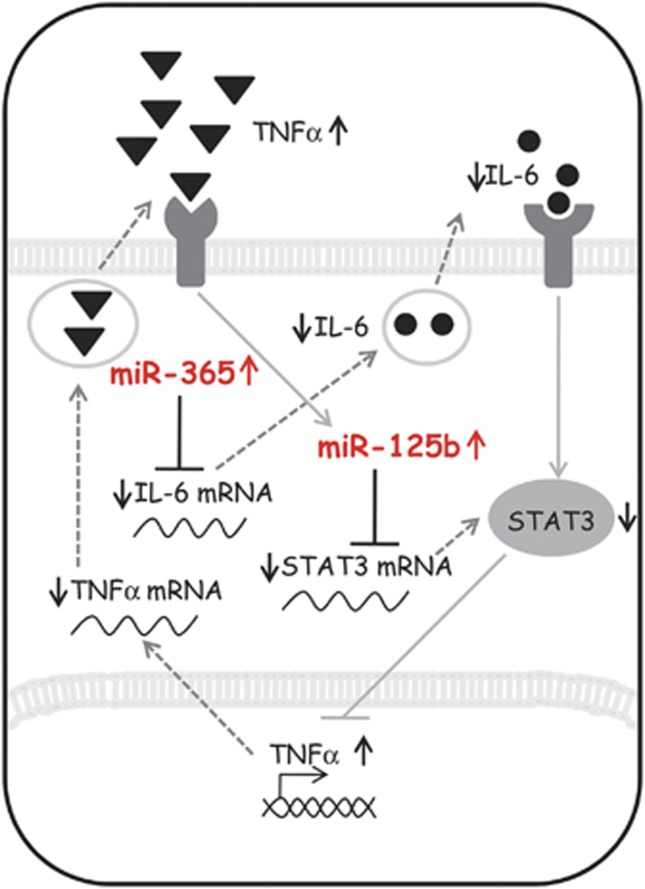

It is well established that IL-6 can mediate pro-inflammatory, but also anti-inflammatory signals,55, 56 with transcriptional TNFα reduction30, 57 as a likely readout of protective pathways, and upregulation of TNFα mostly associated with the detrimental roles of microglia.58 The present finding of upregulated TNFα transcription in ALS microglia thus confirms our previous studies at protein level23 and above all suggests that miR-365 and miR-125b upregulations might directly prevent the anti-inflammatory function of IL-6/STAT3. This is furthermore supported by the suppressing role exerted by inhibitors of miR-365/125b on TNFα mRNA expression that we demonstrated for the first time in SOD1-G93A ALS microglia. In this way, we established a direct causative mechanism involving mutated SOD1 expression and miRNAs dysregulation and giving rise to abnormal cytokine production, a phenomenon typically corresponding to detrimental M1 microglia phenotype (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed interplay of miR-365 and miR-125b in IL-6–STAT3 pathway and TNFα production. Mir-365 and miR-125b are overexpressed in SOD1-G93A microglia and cooperate to repress IL-6–STAT3 pathway by direct targeting. The repression of this pathway increases the activation of TNFα gene transcription. TNFα produced and released in medium is able to upregulate miR-125b, thereby enhancing its own transcription

One of the most widespread microglia activator, extracellular ATP binding to purinergic P2 receptors, is known to markedly increase in the nervous system in response to ischemia, trauma and several neuroinflammatory insults comprising ALS.59 Among P2 receptors, the ionotropic P2X7r subtype mainly expressed in the CNS by microglia exerts several pro-inflammatory functions. In ALS patients, as well as SOD1-G93A models, increased immunoreactivity for P2X7r has been extensively documented in the spinal cord and brain microglia.20 Moreover, we demonstrated that the pro-inflammatory action of microglial P2X7r is enhanced in the SOD1-G93A model and in turn drives increased neurotoxicity.23, 24 Furthermore, a tuned balance of P2X7r activation was proven to be important for disease progression, as shown after ablation of P2X7r in the SOD1-G93A mouse model.60 As several studies have identified a prominent and complex role of miRNAs as key modulators of signal propagation as well as pathological conditions, we decided to verify whether miRNAs might indeed constitute one way through which P2X7r activation participates to ALS pathogenesis and, in particular, to the inflammatory circuit described above. With our work, we proved that extracellular BzATP binding to P2X7r upregulates miRNAs transcriptome that was found similarly upregulated in ALS microglia. This finding highlights miRNAs as crossover in the signal transduction mechanisms of inflammation mediated by both P2X7r and ALS. Most importantly, as BzATP hyperactivates miR-155, mir-125b and miR-146b that are already upregulated in SOD1-G93A microglia, we suggest that these specific miRNAs might constitute an important mechanism by which P2X7r activation exacerbates the detrimental phenotype of ALS microglia. By acting as genetic switchers or fine tuners, in our opinion miRNAs might become stringent modulators of the huge variety of cellular responses carried out by different inflammatory stimuli under both physiological and pathological conditions.

In conclusion, by comparative screening of miRNAs in resting and activated SOD1-G93A microglia, our work has identified selected miRNAs to be used as novel tools for further dissecting and controlling neuroinflammatory mechanisms. In particular, we established a pathogenic mechanism in ALS microglia that correlates the induction of miR-365 and miR-125b to IL6/STAT3 downregulation and consequent enhancement of TNFα production, all responsible for switching microglia toward a detrimental phenotype. Moreover, our results disclosing that purinerigic stimulation per se can regulate miRNAs in brain microglia will encourage the exploitation of purinergic-regulated miRNAs in the context of ALS and additional neuroinflammatory diseases.

Materials and Methods

Primary microglia cell cultures

Mixed glial cultures from the brain cortex were prepared as previously described.23 Briefly, neonatal SOD1-G93A and nt littermate mice were killed and, after removing the meninges, cortices were minced and digested with 0.01% trypsin and 10 μg/ml DNaseI. After dissociation and passage through 70 μm filters, cells were resuspended in DMEM/F-12 media with GlutaMAX (Gibco, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml gentamicine and 100 μg/ml streptomycin/penicillin at a density of 62 500 cells/cm2. After ∼15 days, a mild trypsinization (0.08% in DMEM/F-12 without FBS) was performed for 40 min at 37 °C to remove non-microglial cells. The resultant adherent microglial cells (pure >98%) were washed twice with DMEM/F-12 and kept in 50% mixed glial cells conditioned medium at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 and 95% air atmosphere for 48 h until used.

Microarray

For the miRNA profiling by Agilent Platform (Agilent Technologies, Milan, Italy), total RNA (100 ng) was used. The samples were labeled using the Agilent miRNA Complete Labelling and Hyb Kit (5190-0456) according to Agilent's procedure (G4170-90011, version 2.4, September 2011). The cyanine-3-labeled miRNAs were hybridized on Agilent Mouse miRNA Microarrays 8 × 15K V2 (G4472B) containing 627 mouse miRNAs and 39 mouse viral miRNAs. Hybridizations were performed at 55 °C for 20 h in a rotating oven. Microarrays were then washed with Agilent Gene Expression Buffer 1 for 5 min at room temperature and Agilent Gene Expression Wash Buffer 2 for 5 min at 37 °C. A final treatment with acetonitrile for 1 min at RT was performed. Post-hybridization image acquisition was accomplished using the Agilent scanner G2564B. Data extraction from the images was accomplished by Agilent Feature Extraction ver 10.7 software, using the standard Agilent one-color miRNA expression extraction protocol. Data analyses were performed using Agilent GeneSpringGX, MultiExperimentViewer for Clustering (TIGR), Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA) and R Bioconductor (Seattle, WA, USA).

Target prediction of ALS-dysregulated miRNAs

MiRNA targets were predicted by combinatorial utilization of three different web-based prediction algorithms: TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/), miRanda (http://www.microrna.org) and RNA hybrid.28 We also collected the experimentally in vitro-confirmed targets and inflammatory-related miRNAs by literature curation, and combined them with the above results.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA including small RNA was extracted with TRIZOL (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction and was checked with the Nanodrop 100 System and the Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. QPCR for miRNAs quantification was conducted using miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following reverse transcription using miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All miRNA primers were purchased from Qiagen and the relative expressions were calculated using the comparative CT method with mouse U6 small nuclear RNA as the normalizing control. QPCR for TNFα quantification was performed using SYBR Green select (Applied Biosystem, Milan, Italy) following reverse transcription using Enhanced Avian RT kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). Primers were as follows: TNFα forward 5′-CTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC-3′ TNFα reverse 5′-TTGAGATCCATGCCGTTG-3′ GAPDH forward 5′-CATGGCCTTCCGTGTTTCCTA-3′ GAPDH reverse 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGAT-3′.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Primary microglial cells were lysed with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer's instructions. After DNase treatment (Qiagen), equal amount of total RNA (1 μg) was subjected to retro-transcription by enhanced avian RT-PCR kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 ng of each cDNA were amplified with either mouse IL-6-specific primers (F: 5′-CCAGAAACCGCTATGAAGTTC-3′ R: 5′-CCATTGCACAACTCTTTTCTCAT-3′) or mouse STAT3-specific primers (F: 5′-CAGAAAGTGTCCTACAAGGGCG-3′ R: 5′-CGTTGTTAGACTCCTCCATGTTC-3′). The number of cycles was fixed to 30, after verifying that under these conditions the DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich) presented a linear activity in amplifying cDNAs. Moreover, to verify that the same quantity of DNA was used in each reaction, actin primers (F: 5′-ATCCTGTGGCATCCATGAAAC-3′, R: 5′-AACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTC-3′) were inserted in each PCR for 18 cycles. Amplification products (15 μl of 50) were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), photographed under UV light and quantified using Kodak Image Station 440CF (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA), with Molecular Imaging Software 4.0.1 (Eastman Kodak).

Antibodies

IL-6 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1 : 500) was obtained from Millipore (Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); STAT3 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1 : 1000) from Cell Signalling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA); and β-actin mouse antibody (1 : 2500) from Sigma-Aldrich. HRP-linked anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology Inc.

Protein extraction, SDS-polyacrylamide gel and western blotting

In order to isolate total protein extracts, cells in serum-free medium were collected with ice-cold RIPA buffer (PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) and added with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were kept for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14 000 × g at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and assayed for protein quantification by the BCA method (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Analysis of protein components was performed by polyacrylamide gel separation (Bio-Rad, Laboratories, Milan, Italy) and transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Cologno Monzese, Italy). After saturation, blots were probed overnight at 4 °C, with the specified antibody, and finally incubated for 1 h with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected on X-ray film (Aurogene, Rome, Italy) using ECL Advance western blotting detection kit (Amersham Biosciences). Quantifications were performed using Kodak Image Station.

ELISA

Microglia were incubated for 6 h in fresh media without serum, and mouse IL-6 expression was measured in the supernatants using a commercial mouse IL-6 ELISA kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

MiR-365 and miR-125b constructs, transfection and virus transduction

To generate pPRIME-dsRed-miR-125b and pPRIME-dsRed-miR-365, their respective hairpins were PCR amplified (F: 5′-GAGAAGGCTCGAGAAGGTATATTGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCG-3′ R: 5′-CTAAAGTAGCCCCTTGAATTCCGAGGCAGTAGGCA-3′) from the following templates: miR-125b 5′-TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGTCCCTGAGACCCTAACTTGTGATAGTGA AGCCACAGATGTAACGGGTTAGGCTCTTGGGAGCTTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA-3′ miR-365 5′-TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGATGAGGGACTTTTGGGGGCAGATGTGTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTACATAATGCCCCTAAAAATCCTTATTGCTCTTGCTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA-3′ and cloned into the XhoI and EcoRI sites of the plasmid pPRIME-CMV-dsRED. All pPRIME-dsRed constructs were verified by automated sequencing and then purified and co-transfected together with packaging vectors into HEK-293FT cells. Supernatants were collected after 48 and 72 h, and viral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 26,000 r.p.m. (Ultraclear Tubes, SW28 rotor, and Optima l-100 XP Ultracentrifuge; Beckman Coulter, Milan, Italy) and recovered by suspension in HBSS (Sigma-Aldrich). Titers of viral particles ranged between 106 and 107 TU/ml. Viral particles and polybrene (8 μg/ml) were then added to isolated primary microglia. Lentiviral particles at a multiplicity of infection of 30 and 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the culture. Supernatant was removed 5 h after infection and replaced with DMEM-F-12 medium containing 10% FBS. In all the experiments, the efficiency of microglia transduction was at least 90%, as determined by counting the number of microglia expressing the dsRed molecule and counterstaining nuclei with Höechst 33258 (1 μg/ml for 5 min) by means of a fluorescent microscope. All experiments were performed at 96 h post infection.

Cell transfection

Primary microglia (5 × 105 per well) were plated for 48 h and transfection of 20 nM miRIDIAN Hairpin inhibitors (Dharmacon Products, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was performed with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers' instructions. We used a negative control inhibitor based on Caenorhabditis elegans miRNAs not found in humans (miRIDIAN miRNA hairpin inhibitor negative control).

Luciferase assay

The 3′-UTR of the mouse IL-6 was PCR amplified with XbaI-flanked primers (F: 5′-GCGCGctctagaTAGTGCGTTATGCCTAAGCA-3′ R: 5′-GCGCGctctagaGTTTGAAGACAGTCTAAACAT-3′). The PCR products were purified, digested and cloned downstream of the luciferase-coding region in the pRL-TK vector (Promega, Milan, Italy). pRL-TK containing mutant IL-6 UTR was generated by PCR site-directed mutagenesis (F: 5′-GCATATCAGTTTGTGcACAgTCCTCACTGTGGTCAG-3′ R: 5′-CTGACCACAGTGAGGAcTGTgCACAAACTGATATGC-3′) using wild-type IL-6 UTR plasmid as a template, followed by digestion with Dpn1. Human HEK293T cell line was co-transfected with respective luciferase constructs and pprime-miR-365 or empty vector along with firefly luciferase expression plasmid (PGL3) as a transfection control using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells were lysed and analyzed for relative luciferase activity using the Dual Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±S.E.M. Normality of data was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical differences were verified by Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test or nonparametric Wilcoxon's Mann–Whitney test using MedCalc (Medcalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). *P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Antonino Cattaneo (EBRI, Rome) for critical discussion and suggestions during microarray studies. We thank Agilent Technologies for technical support. This work was supported by Italian Ministry for Education, University and Research in the framework of the Flagship Project NanoMAX, FIRB RBAP10L8TY, and Fondazione Roma.

Glossary

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- nt

non-transgenic

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase

- miRNA

microRNA

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- QPCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- UTR

untraslated region

- (BzATP)

2′(3′)-O-(4-Benzoylbenzoyl)adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Material

References

- Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377:942–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PM. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated with mutations in the CuZn superoxide dismutase gene. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s11910-996-0008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.8209258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synofzik M, Fernandez-Santiago R, Maetzler W, Schols L, Andersen PM. The human G93A SOD1 phenotype closely resembles sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:764–767. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.181719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobsiger CS, Cleveland DW. Glial cells as intrinsic components of non-cell-autonomous neurodegenerative disease. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1355–1360. doi: 10.1038/nn1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka K, Boillee S, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, McAlonis-Downes M, Mikse OR, et al. Mutant SOD1 in cell types other than motor neurons and oligodendrocytes accelerates onset of disease in ALS mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7594–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802556105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beers DR, Henkel JS, Xiao Q, Zhao W, Wang J, Yen AA, et al. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU.1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16021–16026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boillee S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao B, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS, Appel SH. Transformation from a neuroprotective to a neurotoxic microglial phenotype in a mouse model of ALS. Exp Neurol. 2012;237:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai R, Ahmed SA. MicroRNA, a new paradigm for understanding immunoregulation, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Transl Res. 2011;157:163–179. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels BM, Hutvagner G. Principles and effects of microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Oncogene. 2006;25:6163–6169. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5003–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019055108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhang S, Weber J, Baxter D, Galas DJ. Export of microRNAs and microRNA-protective protein by mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7248–7259. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Barteneva N, Krichevsky AM, Weiner HL. MicroRNA-124 promotes microglia quiescence and suppresses EAE by deactivating macrophages via the C/EBP-alpha-PU.1 pathway. Nat Med. 2011;17:64–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada SJ, Finkbeiner S. Pathogenic TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: disease-associated pathways. Rev Neurosci. 2010;21:251–272. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2010.21.4.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haramati S, Chapnik E, Sztainberg Y, Eilam R, Zwang R, Gershoni N, et al. miRNA malfunction causes spinal motor neuron disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13111–13116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006151107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AH, Valdez G, Moresi V, Qi X, McAnally J, Elliott JL, et al. MicroRNA-206 delays ALS progression and promotes regeneration of neuromuscular synapses in mice. Science. 2009;326:1549–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1181046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedle SA, Brautigam VM, Nikodemova M, Wright ML, Watters JJ. The P2X7-Egr pathway regulates nucleotide-dependent inflammatory gene expression in microglia. Glia. 2011;59:1–13. doi: 10.1002/glia.21071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volonté C, Apolloni S, Skaper SD, Burnstock G. P2X7 receptors: channels, pores and more. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2012;11:705–721. doi: 10.2174/187152712803581137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanovas A, Hernandez S, Tarabal O, Rossello J, Esquerda JE. Strong P2 × 4 purinergic receptor-like immunoreactivity is selectively associated with degenerating neurons in transgenic rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:75–92. doi: 10.1002/cne.21527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiangou Y, Facer P, Durrenberger P, Chessell IP, Naylor A, Bountra C, et al. COX-2, CB2 and P2X7-immunoreactivities are increased in activated microglial cells/macrophages of multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord. BMC Neurol. 2006;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Ambrosi N, Finocchi P, Apolloni S, Cozzolino M, Ferri A, Padovano V, et al. The proinflammatory action of microglial P2 receptors is enhanced in SOD1 models for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Immunol. 2009;183:4648–4656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S, Parisi C, Pesaresi MG, Rossi S, Carri MT, Cozzolino M, et al. The NADPH oxidase pathway is dysregulated by the P2X7 receptor in the SOD1-G93A microglia model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Immunol. 2013;190:5187–5195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Xiao SB, Xu P, Xie Q, Cao L, Wang D, et al. miR-365, a novel negative regulator of interleukin-6 gene expression, is cooperatively regulated by Sp1 and NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:21401–21412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz E, Hofer MJ, Unzeta M, Campbell IL. Minimal role for STAT1 in interleukin-6 signaling and actions in the murine brain. Glia. 2008;56:190–199. doi: 10.1002/glia.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger J, Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W451–W454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surdziel E, Cabanski M, Dallmann I, Lyszkiewicz M, Krueger A, Ganser A, et al. Enforced expression of miR-125b affects myelopoiesis by targeting multiple signaling pathways. Blood. 2011;117:4338–4348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderka D, Le JM, Vilcek J. IL-6 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor production in cultured human monocytes, U937 cells, and in mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:3517–3523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Y, Wang C, Manes TD, Pober JS. Cutting edge: TNF-induced microRNAs regulate TNF-induced expression of E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human endothelial cells: feedback control of inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:21–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–5089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH. Contribution of systemic inflammation to chronic neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;120:277–286. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0722-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im HI, Kenny PJ. MicroRNAs in neuronal function and dysfunction. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe M, Bonini NM. MicroRNAs and neurodegeneration: role and impact. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Git A, Dvinge H, Salmon-Divon M, Osborne M, Kutter C, Hadfield J, et al. Systematic comparison of microarray profiling, real-time PCR, and next-generation sequencing technologies for measuring differential microRNA expression. RNA. 2010;16:991–1006. doi: 10.1261/rna.1947110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo K, Glass CK. Microglial cell origin and phenotypes in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:775–787. doi: 10.1038/nri3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Siddiqui S, Gabriely G, Lanser AJ, Dake B, Murugaiyan G, et al. Modulating inflammatory monocytes with a unique microRNA gene signature ameliorates murine ALS. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3063–3087. doi: 10.1172/JCI62636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas AH, Boddeke HW, Biber K. Region-specific expression of immunoregulatory proteins on microglia in the healthy CNS. Glia. 2008;56:888–894. doi: 10.1002/glia.20663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras J, Rao DS. MicroRNAs in inflammation and immune responses. Leukemia. 2012;26:404–413. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri AA, So AY, Sinha N, Gibson WS, Taganov KD, O'Connell RM, et al. MicroRNA-125b potentiates macrophage activation. J Immunol. 2011;187:5062–5068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Alexandrov PN. Regulation of complement factor H (CFH) by multiple miRNAs in Alzheimer's disease (AD) brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukiw WJ, Pogue AI. Induction of specific micro RNA (miRNA) species by ROS-generating metal sulfates in primary human brain cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1265–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill LA, Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappa B a crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:252–258. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Spencer NY, Pantazis NJ, Engelhardt JF. Alsin and SOD1(G93A) proteins regulate endosomal reactive oxygen species production by glial cells and proinflammatory pathways responsible for neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:40151–40162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup V, Phaneuf D, Dupre N, Petri S, Strong M, Kriz J, et al. Deregulation of TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis triggers nuclear factor kappaB-mediated pathogenic pathways. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2429–2447. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Becker Buscaglia LE, Barker JR, Li Y. MicroRNAs in NF-kappaB signaling. J Mol Cell Biol. 2011;3:159–166. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu IM, Chen A, Zheng Y, Kosaras B, Tsiftsoglou SA, Vartanian TK, et al. T lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17913–17918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West M, Mhatre M, Ceballos A, Floyd RA, Grammas P, Gabbita SP, et al. The arachidonic acid 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor nordihydroguaiaretic acid inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha activation of microglia and extends survival of G93A-SOD1 transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2004;91:133–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weydt P, Yuen EC, Ransom BR, Moller T. Increased cytotoxic potential of microglia from ALS-transgenic mice. Glia. 2004;48:179–182. doi: 10.1002/glia.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara T, Ishigaki S, Yamamoto M, Liang Y, Niwa J, Takeuchi H, et al. Differential expression of inflammation- and apoptosis-related genes in spinal cords of a mutant SOD1 transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2002;80:158–167. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, et al. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb GB, Khan AA, Canner D, Hiatt JB, Shendure J, Darnell RB, et al. Transcriptome-wide miR-155 binding map reveals widespread noncanonical microRNA targeting. Mol Cell. 2012;48:760–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LH, Li H, Li JP, Zhong H, Zhang HC, Chen J, et al. miR-125b suppresses the proliferation and migration of osteosarcoma cells through down-regulation of STAT3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;416:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813b:878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittau B, Zhou X, Ming M, Krieglstein K. IL6 protects MN9D cells and midbrain dopaminergic neurons from MPP+-induced neurodegeneration. Neuromol Med. 2012;14:317–327. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulich TR, Guo KZ, Remick D, del Castillo J, Yin SM. Endotoxin-induced cytokine gene expression in vivo. III. IL-6 mRNA and serum protein expression and the in vivo hematologic effects of IL-6. J Immunol. 1991;146:2316–2323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KM, Bowers WJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediated signaling in neuronal homeostasis and dysfunction. Cell Signal. 2010;22:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G, Krugel U, Abbracchio MP, Illes P. Purinergic signalling: from normal behaviour to pathological brain function. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:229–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apolloni S, Amadio S, Montilli C, Volonté C, D'Ambrosi N. Ablation of P2X7 receptor exacerbates gliosis and motoneuron death in the SOD1-G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4102–4116. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.