Abstract

Genome-wide association studies have been successful in identifying loci that underlie continuous traits measured at a single time point. To additionally consider continuous traits longitudinally, it is desirable to look at SNP effects at baseline and over time using linear-mixed effects models. Estimation and interpretation of two coefficients in the same model raises concern regarding the optimal control of type I error. To investigate this issue, we calculate type I error and power under an alternative for joint tests, including the two degree of freedom likelihood ratio test, and compare this to single degree of freedom tests for each effect separately at varying alpha levels. We show which joint tests are the optimal way to control the type I error and also illustrate that information can be gained by joint testing in situations where either or both SNP effects are underpowered. We also show that closed form power calculations can approximate simulated power for the case of balanced data, provide reasonable approximations for imbalanced data, but overestimate power for complicated residual error structures. We conclude that a two degree of freedom test is an attractive strategy in a hypothesis-free genome-wide setting and recommend its use for genome-wide studies employing linear-mixed effects models.

Keywords: linear-mixed effects model, genome-wide association study, longitudinal data, power and type I error calculations

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies have been successful in detecting reproducible genetic associations for common variants with modest effect sizes, provided large samples can be meta-analyzed to achieve sufficient power [Ku et al., 2010]. Efforts to date have focused almost exclusively on traits that were measured at a single time point [Teslovich et al., 2010], or averaged across multiple time points [Kathiresan et al., 2007]. Some of the current genome-wide association (GWA) projects will continue to use cross-sectional data, but vary the type of genetic measurement, such as evaluating whole exome or whole genome sequencing data [Willer and Mohlke, 2012], or will use genetic measurements imputed to the 1000 genomes project [1000 Genomes Project Consortium, 2010]. Other efforts will seek to find genes by using new analytic approaches to existing GWA summary statistics, such as the use of polygenic risk scores [International Schizophrenia Consortium et al., 2009; Witte and Hoffmann, 2011], penalized regression [Ayers and Cordell, 2010; Shi et al., 2011], the incorporation of functional annotation data [Knight et al., 2011], or the use of multiple, correlated phenotypes [O’Reilly et al., 2012]. Still other efforts, however, will seek to use the full information that is available in repeatedly measured, continuous data that is collected in many cohorts, rather than focusing on a single measurement point, or a scalar summary measure of these points [Rasmussen-Torvik et al., 2010].

Linear-mixed effect (LME) models, or random effect models, are a compelling way to model continuous, repeatedly measured traits if assumptions of multivariate normality can be met. LME models have been shown to be more powerful compared to some simpler approaches for modeling these data [Sikorska et al., 2013]. LME models are flexible in that they allow for incorporation of random effects to handle the dependency of repeated measures, and have many options for modeling the covariance pattern of the within-individual errors that may exist even after the modeling of random effects [Laird and Ware, 1982]. By incorporating a random intercept, or incorporating both a random intercept and slope, a mixed effect model framework allows the phenotype to be treated as a latent trait. This potentially reduces measurement error so that the interpretation at a single time point within this framework can offer increased power compared to an interpretation from a cross-sectional design with only one measurement occasion [Singer and Willett, 2003]. Further, the random terms properly acknowledge the heterogeneity of population trajectories that is likely inherent in many traits, both in terms of the baseline and slope values [Diggle et al., 2002]. LME models have the desirable property that the regression estimates are unbiased in the presence of imbalanced data, provided both the mean model and the covariance structure are properly specified [Laird and Ware, 1982]. Finally, associations detected for SNP effects over time may validate associations detected at baseline, or SNPs may correlate with the rate of change per se, rather than an instrinsic, but unchanging, trait level, depending on the window of time an individual is evaluated. Published reports of candidate gene associations that have focused separately on baseline or change effects in the context of a LME model have been published for numerous traits including cognition [Benke et al., 2011], cardiovascular outcomes [Webster et al., 2009], and child growth measures [Mook-Kanamori et al., 2011]. These examples, however, do not address the estimation of intrinsic level and change simultaneously.

In a hypothesis-free design such as a genome-wide scan, simultaneous interpretation of the two parameters of interest, the SNP main effect and the SNP effect over time, are desirable. This, however, raises concern about inflated type I error when performing LME models for millions of SNPs across the genome. Given the number of multiple comparisons, the usual genome-wide significance threshold of 5 × 10−8 [Dudbridge and Gusnanto, 2008; Risch and Merikangas, 1996] may no longer be appropriate. A simple method to maintain the accepted false-positive rate would be to employ a simple Bonferroni correction (5/2 × 10−8) and interpret each parameter accordingly, but this approach is too conservative particularly when interpreting many correlated tests, and will make it more difficult to achieve significance [Bland and Altman, 1995]. A second approach would be to make an adjustment for the lower order term, in this case the SNP main effect. A third approach would be to conduct a joint two degree of freedom likelihood ratio test at the usual genome-wide significance level, though one would expect some loss of power on account of the additional degree of freedom if only a single parameter is associated. It may be, however, that loss of power is minimal in this situation for a joint test, and thus offer a reasonable compromise in a hypothesis free design. In fact, Kraft et al. [2007] used closed form solutions to determine power and sample size for a gene–environment case–control design, and concluded that, for situations where effect sizes were present for only a gene or only an environmental variable, power for a joint test was often similar to a single parameter test, and was more powerful when both gene and environment effects were present. This latter point is important, because for many situations a study will be underpowered to detect either baseline or change effect of a SNP, but may achieve sufficient power by combining information from both. This is perhaps the most compelling reason to carry out a longitudinal data analysis: SNPs just below the genome-wide significance threshold from cross-sectional analysis may achieve significance in this setting, and previously undetected loci may be identified using data that has already been collected by analyzing the available longitudinal measures.

For a longitudinal study employing LME analysis, considerations are somewhat different than a gene–environment interaction study. Rather than focusing on prevalence for an environmental variable, the distribution of time may have a significant influence on power for longitudinal outcomes. While closed form solutions have been proposed [Fizmaurice et al., 2004] for LMEs, these equations assume perfect balance and complete data, unlikely to be the case in any cohort study. Simulation is therefore the appropriate method to generate reliable power estimates. We determined power for joint tests of the two SNP parameters simultaneously, including the likelihood ratio two degree of freedom test (2dfLRT), using simulation across a range of generating effect sizes and compared it to the power achieved by using a likelihood ratio single degree of freedom test that employs varying standards for calculating the Bonferroni correction. We also compare power for single parameter tests to that obtained with a closed-form solution.

Materials and Methods

Background: LMEs Model

Continuous, repeated measures data can be analyzed using LMEs models, provided the underlying assumptions are met. Typically for longitudinally measured traits such as cognition, researchers are interested in considering a random intercept and slope. Such a model for the ith subject at the jth measurement occasion can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where Yij is the observed response at time j for the ith subject, β0 is the population intercept and β1 is the average population linear change over time. In this model, the bi = (b0i, b1i) represent subject-specific effects such that b0i is an individual random intercept and b1i is an individual random slope, and both terms assume a normal distribution [b0i ~ N(0, σ200), b1i ~ N(0, σ211)]. The random terms can be correlated so that cor(b0i, b1i) = ρ. The eij are the within subject errors at time j with ei ~ N(0, σ2e), although this latter assumption can be relaxed to consider compound symmetry or autoregressive structures for the covariance of the within-subject random errors.

Data Simulation to Determine Power and Bias

The Study Example

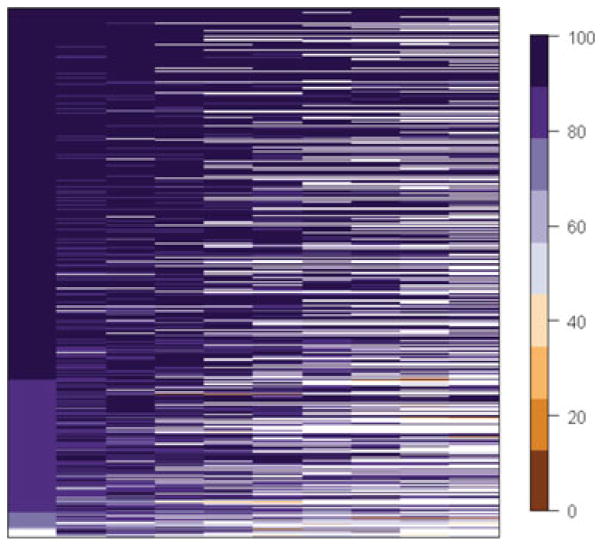

Our simulation parameters are based on individuals aged 65 years and older with at least three of 10 possible measurements for a cognitive test score in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). The CHS is a prospective, longitudinal study begun in 1989, with 5,201 participants recruited using random sampling from HCFA Medicare files [Fried et al., 1991]. The model characteristics for the longitudinal cognition trait were borrowed from an optimized model that included 3,575 white individuals from the original cohort included in a candidate study of interleukin-1 genes [Benke et al., 2011]. This model included confounders such as age, gender, and health status as well as their first-order interactions; time was determined to be linear using goodness of fit tests. Annual cognitive test scores were collected using the modified minimental state exam (3MS), a test of global cognition that ranges from 0 to 100 [Teng and Chui, 1987]. The average follow-up time for this group was 7.31 years (SD = 2.26). Because we had access to the raw study data, we were able to use the observed measurement times. As part of the CHS design, a second African American (AA) cohort began collection in 1992, and we borrowed model parameters from an optimized model of 481 individuals and similar covariates from the same candidate gene study. The AA participants also had at least three of seven possible measurements on the 3MS, and the average follow-up time for this group was 5.26 (SD = 1.21) years. In order to provide a visual display of the data that the longitudinal simulation was based upon, we created a lasagna plot [Swihart et al., 2010], which creates a box for each measurement occasion per individual, and colors the box according to the trait value observed at that measurement occasion. Figure 1 displays this plot for the sample of 1,800 CHS participants from the original cohort whose measurement occasion was used in our simulation, although the entire sample of 3,575 participants were used to obtain the optimized model parameters displayed in Table 1. The lasagna plot is useful to get a sense of the proportion of missing data in the sample (coded as a white box). It can also be seen that the majority of the sample began follow up with scores above 80, and very few subjects fell below a score of 60.

Figure 1.

Lasagna plot of the 1,800 CHS participants with three or more measures over a 10-year follow-up whose observed measurement occasions were selected for longitudinal data simulation. A single box represents a measurement for a single subject i at a given measurement time j. Boxes are shaded white if the 3MS score is missing at that occasion for that individual. The shading reflects a binned 3MS score such that very high scores (90 or above) will be dark purple and very low scores (10 or less) are brown. The legend provides color coding for all the bins with nonmissing 3MS score.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates informing the simulated longitudinal data. Parameter estimates reflect the results from an optimized, nongenetic model from a published candidate gene association study of cognitive trajectories in older adult participants of the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). We assume a GWAS sample of 1,800. The symbols are: m = the total number of individuals simulated; N1 = the total number of simulated measurements for the balanced design; N2 = the total number of simulated measurements for the imbalanced design; σ00 = standard deviation of the random intercepts; σ00 = standard deviation of the random slopes; σe = residual standard deviation within subjects; ρ = correlation between the random intercepts and random slopes; β0 = fixed effects intercept, or the average 3MS score (range 0–100) in the population; β1 = fixed effects slope, or the average annual decrease in 3MS score

| Parameter | Value for white cohort | Value for AA cohort |

|---|---|---|

| m | 1,800 | 1,800 |

| N1 | 18,000 | 18,000 |

| N2 | 14,578 | 14,578 |

| σ00 | 4.67 | 8.28 |

| σ11 | 1.76 | 1.48 |

| σe | 4.74 | 4.66 |

| ρ | 0.15 | 0.55 |

| β0 | 89.8 (3MS score) | 78.6 |

| β1 | −1.22 (change in 3MS score) | −0.80 |

Data Simulation for Longitudinal 3MS Score

The parameters we set for our simulation of the longitudinal data are shown in Table 1, and include estimates for the variance of the random intercepts and slopes, the within subject errors, and the population, fixed effects estimates for intercept and time. To create a distribution of time (tij) that reflects imbalance observed in real data, we used the observed measurement times for each individual, which also ensures that the total number of observed time points N is constant across each replicate. Measurement occasions were imbalanced, but attempted at 1-year intervals over 10 years of follow up from the baseline measurement. We simulated a balanced dataset by assuming that 1,800 individuals were measured at exactly the same time with no missing occasions. We initially assumed that the within subject errors were independently distributed (Ind), and therefore sampled errors from a normal distribution with specified variance σe2. We also explored a covariance structure for the within-individual errors that reflected a continuous autoregressive structure of order one (corCAR1), which allows the observations to be made at nonevenly spaced times. Thus, simulations were organized into four groups:

Independent residual errors; balanced data (Ind-Bal).

Independent residual errors; imbalanced data (Ind-ImBal).

eij structure corCAR1; balanced data (corCAR1-Bal).

eij structure corCAR1; imbalanced data (corCAR1-ImBal).

For the corCAR groups C and D, the distribution of the within-subject errors can be written as ei ~

(0,σ2Ri) where:

(0,σ2Ri) where:

and Ji is the number of observed time points for the ith subject.

To generate SNP data, we sampled genotypes (a value of 0, 1, or 2) from a multinomial distribution, where the genotype frequencies were determined assuming Hardy–Weinberg proportions, based on a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.20. We set the fixed effects parameter for the SNP main effect (β2 range 0–1.4 by .20) and the SNP effect over time (β3 range 0–0.24 by .02), along with all other parameters described above. Random effects (b0i and b1i) were sampled from a multivariate normal distribution, specifying a negative correlation between the intercepts and slopes (see Table 1). Residual errors (eij) were sampled from a normal distribution with a specified sigma matrix that reflected the assumed covariance structure (independence or corCAR1). These values were then inserted into equation (2):

| (2) |

We were interested in interpreting both the SNP main effect, β2, which represents the average difference at baseline between the referent genotype and the risk genotype, and the SNP effect over time, β3, which represents the departure from the referent genotype average slope over time. All SNP parameters assume an additive genetic model, so that each copy of the minor allele increases the cognitive trait by an equal amount. We additionally considered lower minor allele frequencies for the SNP of 0.10, 0.05, and 0.02.

The False-Positive Rate

The direct calculation of a genome-wide false-positive rate when interpreting two SNP parameters (β2 and β3 from equation (2)) would be ideal. This would require that a null dataset is simulated such that no allele is designed to be associated with the outcome, and a genome-wide scan would then be performed on this dataset; the simulation and association step would then be repeated 5,000–10,000 times. Such an approach, however, demands an enormous amount of computing time. Even a pruned subset of the observed genotypes on the order of 100,000 SNPs requires very demanding computing time, and was thus determined to be prohibitive. We instead decided to investigate the false-positive rate in two ways. To look within a genome-wide context, we used data from 1,262 individuals with GWA data from an available cohort, and pruned the full set of 529,596 SNP using PLINK, specifying the independent pairwise option and requiring that the remaining subset of pruned SNPs were not correlated with any other SNPs in the subset at an r2 of 0.50. Of the original set of genotyped SNPs, we were left with 226,097 SNPs in the pruned subset. We then simulated one null replicate where β2 and β3 were set to zero and performed a genome-wide scan. For the sake of comparison, the QQ plot of the −log10(P-values) for β2 and β3 were shown separately. We then performed a QQ plot for the −log10(P-value) corresponding to the minimum P-value for β2 and β3. This latter plot is designed to show whether the genome-wide type I error is inflated for a single replicate when interpreting both β2 and β3 from each SNP included in the genome-wide scan. The lambda values corresponding to each QQ plot were calculated using the estlambda option in the GenABEL software (Aulchenko, 2007).

We also looked at the false-positive rate for a single SNP, using the null simulation framework to generate a family-wide error rate (FWER). Our interest here was to calculate a type I error that reflects the percentage of SNP main effects or SNP effects over time that are falsely positive, and is in contrast to calculating the type I error for a single parameter. We computed the FWER by simulating a null dataset where both β2 and β3 are set to zero, and recording a false positive if either or both P-values corresponding to the parameters were below an alpha significance level of 0.05, and call this FWER0.05|0.05. We calculate another family-wise error rate, FWER0.05|0.025, by recording for the same null dataset a false positive if the P-value corresponding to the SNP effect over time was less than 0.05 or the P-value corresponding to the SNP main effect was less than 0.025. The latter calculation reflects the effort to control the inflation in type I error by creating a more stringent criteria for the lower order SNP main effect. Finally, we calculate FWER0.025|0.025, so that both effects are not considered significant unless the P-values fall below an alpha level of 0.05/2, or 0.025, and this represents our most stringent Bonferroni control strategy.

Power Determination

A total of 1,000 simulated replicates were created for each combination of SNP main effect (β2) and SNP effect over time (β3) parameters. For each simulation, four different LME models were performed and statistics extracted. The first model was a null model that did not include any genetic parameters (equation (1)). The second full model included the intercept, time, SNP and SNP effect over time (equation (2)). The third model included only the intercept, time and SNP effect (equation (3)) and finally, a fourth model included only the intercept, time and SNP effect over time (equation (4)).

| (3) |

| (4) |

The −2 log likelihoods from each model were recorded and used to calculate P-values according to a likelihood ratio test described in equation (5):

| (5) |

Here, the maximum likelihood estimation for the model parameters is carried out under a null hypothesis, and then under an alternative hypothesis; the statistic has an asymptotic chi-squared distribution with k degrees of freedom, where k is difference in the number of parameters between the null and alternative models. The lmer function implemented in the lme4 package in R was used to estimate models with independent error structures, and the lme function implemented in the nlme package in R was used to estimate models with corCAR1 error structures. When testing for the SNP effect, the alternative log likelihood is calculated from equation (2) and the null log likelihood is calculated from equation (4), so that there is a single degree of freedom (k = 1). When testing for the SNP effect over time, the alternative model is calculated from equation (2) and the null model is calculated from equation (3), so that there is a single degree of freedom (k = 1). The 2dfLRT reflects an alternative model described in equation (2) and a null model described in equation (1), so that k = 2. The P-values were obtained by taking the difference of the −2 log likelihoods from the alternative and null model, and then referring to the appropriate chi-squared distribution. Power was calculated by recording whether each replicate produced a P-value below the established alpha level, and summing across all 1,000 replicates. We computed the power separately for the SNP main effect term, β2, and the SNP effect over time, β3, at an alpha level of 0.025. We compared this to the power to using two different joint tests. The first joint test was the 2dfLRT, and a second joint test where a significant SNP “hit” was recorded if the P-value for either β2 or β3 fell below an alpha level of 0.025. This latter approach is termed P0.025|0.025.

Closed Form Power Calculations

We selected the equations provided in Fitzmaurice et al. [2004] for a closed form calculation for a single degree of freedom test, assuming an alpha level of 0.025. This test is based on an independent two sample t-test, and takes the form described in equation (6); power is determined by the area under the standard normal curve that lies to the left of Z(1−γ).

| (6) |

Here, the variance is a function of the between and within subject variance components and is computed as shown in equation (7) [Fizmaurice et al., 2004]. In our case, the π represents the minor allele frequency. The δ represents the effect size, reflecting the difference for the 3MS score, at baseline or in the annual change over time, for each copy of the minor allele. As there is no accepted closed form solution for a two degree of freedom test in the context of LMEs models, we did not pursue this.

| (7) |

Results

Findings for the False-Positive Rate

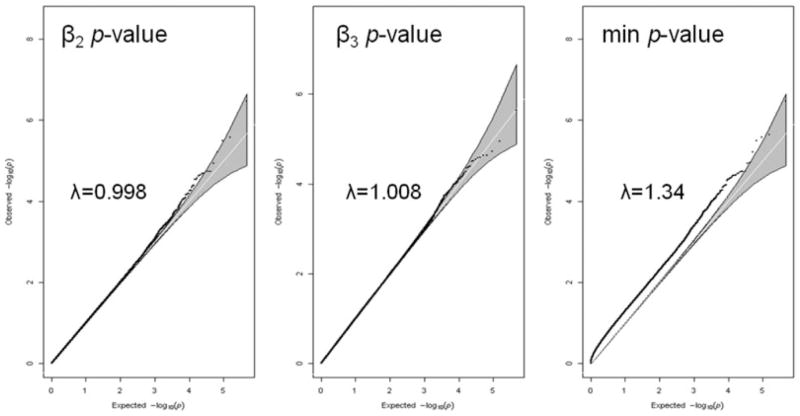

Figure 2 displays the QQ plots for a single null replicate for the SNP main effect, the SNP effect over time, and the minimum P-value corresponding to these two parameters. It can be seen that inflation of type I error is minimal or not present for each parameter considered separately (λ for β2 = 0.998, λ for β3 = 1.008), but inflation is clearly present for the case where the minimum P-value is considered (λ for minimum P-value for β2 or β3 = 1.34). This suggests that that a genome-wide false-positive rate that is calibrated for a single term is not sufficiently conservative when interpreting two terms from the same model. This is a key point, as the examination of QQ and manhattan plots for each term separately is equivalent to looking at the minimum P-value.

Figure 2.

QQ plot of our simulated null GWA. The left most panel shows the plot where the P-value corresponds to the SNP main effect (β2), the middle panel shows the P-value corresponding to the SNP effect on the annual change over time (β3), and the right most panel shows the plot where the P-value corresponds to the minimum of the P-values for β2 or β3.

Our family-wide error rate where no correction was made to adjust significance level (FWER0.05|0.05) was calculated to be 0.092, suggesting that the concern for false positives is indeed a valid one when interpreting two parameters from a single model and indicates that some adjustment for significance level is in order. We also considered the case where the higher order β3 is interpreted at the 0.05 alpha level, but the lower order β2 is interpreted at an adjusted 0.025 alpha level. The FWER0.05|0.025 was observed to 0.075, is still inflated for this strategy. Inflation was also present at lower minor allele frequencies (we explored 0.10, 0.05, and 0.02), ranging between 0.06–0.07 for FWER0.05|0.025 and 0.08–0.085 for FWER0.05|0.05. Thus, for the power calculations to follow, we only consider the case where both β2 and β3 are interpreted at the 0.025 alpha level. The FWER0.025|0.025 was acceptable at 0.049.

As seen in the first row of Table 2 columns 3 through 5, the observed type I errors for each single parameter were near the established alpha level within acceptable limits, but not so low as to be considered overly conservative. We did observe a slight inflation for the parameters for the SNP effects over time (β3) when the SNP term is set to zero; this may be due to the fact that some variation in the calculation of type I error will occur due to the finite nature of the 1,000 replicates performed for this exercise, or it may indicate a more complex issue with modeling subtle correlation structures over time. It can also be seen that when β2 is set to zero, the type I error for the SNP term is preserved as the SNP over time generating effect increases, as would be expected since independence between these two parameters was assumed. Similarly, when β3 is set to zero, the type I error for this parameter is preserved at increasing levels for the SNP generating effect. For the 2dfLRT test, type I error is 0.049, an acceptable finding.

Table 2.

Simulated power by the generating parameters for the SNP effect (β2) and the SNP effect over time (β3) for the White CHS Cohort. Simulated power by the generating parameters for the SNP effect (β2 from equation (2)) and the SNP effect over time (β3 from equation (2)). Results reflect a LMEs model with parameters as indicated in Table 1 for the white cohort, assuming balanced data and eij distributed independently. The black horizontal lines group the SNP effects by size so that the top grouping reflects no SNP effect, the middle grouping reflects a moderate SNP effect, and the bottom grouping reflects a strong SNP effect. The shading is designed to aid the reader in comparing the set of SNP effects over time across varying values for β2 so that lighter shades reflect weaker SNP effects over time, and the shades darken as β3 increases. Bold font within each grouping highlights the comparisons that the authors find most relevant and is discussed in the text. Based on type I error findings, the authors only recommend interpreting separate SNP effects at the 0.025 alpha level indicated in columns 3 and 4, or using the joint tests indicated in columns 6 and 7 to interpret SNP parameters. For our simulated example, the 2dfLRT (column 6) is the recommended strategy

| SNP effect (β2) | SNP effect over time (β3) | Power for β2 | Power for β3 | Power 2dfLRT | Power0.025|0.025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α=0.025 | α =0.025 | α =0.05 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.056 | 0.049 | 0.049 |

| 0 | 0.04 | 0.019 | 0.044 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.063 |

| 0 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.119 | 0.197 | 0.138 | 0.139 |

| 0 | 0.12 | 0.017 | 0.279 | 0.37 | 0.282 | 0.292 |

| 0 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.456 | 0.568 | 0.465 | 0.47 |

| 0 | 0.20 | 0.019 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.647 | 0.659 |

|

| ||||||

| 0.4 | 0 | 0.28 | 0.024 | 0.048 | 0.313 | 0.298 |

| 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.319 | 0.045 | 0.083 | 0.369 | 0.347 |

| 0.4 | 0.08 | 0.308 | 0.122 | 0.198 | 0.437 | 0.391 |

| 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.298 | 0.258 | 0.354 | 0.542 | 0.481 |

| 0.4 | 0.16 | 0.324 | 0.47 | 0.574 | 0.73 | 0.643 |

| 0.4 | 0.20 | 0.325 | 0.66 | 0.775 | 0.832 | 0.774 |

|

| ||||||

| 0.8 | 0 | 0.93 | 0.027 | 0.049 | 0.915 | 0.933 |

| 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.044 | 0.077 | 0.901 | 0.913 |

| 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.927 | 0.134 | 0.199 | 0.938 | 0.935 |

| 0.8 | 0.12 | 0.919 | 0.266 | 0.367 | 0.954 | 0.938 |

| 0.8 | 0.16 | 0.92 | 0.453 | 0.567 | 0.966 | 0.955 |

| 0.8 | 0.20 | 0.909 | 0.643 | 0.75 | 0.982 | 0.969 |

Simulated Power Calculations

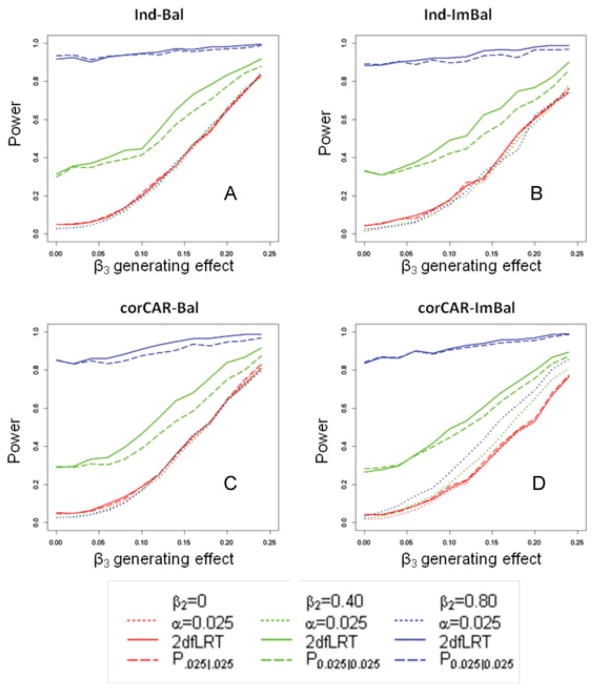

Power calculations for a subset of the different combinations of generating effects for β2 and β3 are provided in Table 2. A more comprehensive set of scenarios are graphically represented in Figure 2 for the SNP effect over time and Figure 3 for the SNP effect. As expected, power for each term increases as the generating effect for that term increases.

Figure 3.

A–D. Each panel shows the simulated power by the SNP change over time (β3) generating effect size. Panel A shows these calculations for the simplest case where data is balanced and the eij are independently distributed (Ind-Bal). Panel B shows the same, but the eij are distributed according to a continuous autoregressive structure of order 1 (corCAR1-Bal). Panel C shows the case where the data is imbalanced and the eij are independently distributed (Ind-ImBAL), and Panel D the most complicated cases where data is imbalanced and the eij are distributed according to a continuous autoregressive structure of order 1 (corCAR1-Imbal). Dotted lines represent power when the parameter is interpreted at alpha 0.025; dashed lines represent power when the parameter is interpreted at alpha 0.05; solid lines represent power using the 2dfLRT. Red denotes when the SNP effect is null (β2 = 0), green denotes when the SNP effect is models (β2 = 0.40), and blue denotes when the SNP effect is strong (β2 = 0.80).

Our main interest was to compare the power of the 2dfLRT to the single degree of freedom test and to the strategy where a SNP “hit” is called if either SNP term is significant, labeled P0.025|0.025. We first considered the comparison to the tests for the SNP effect over time, and to do this, we looked within constant levels for the SNP effect. Figure 3A suggest that when the SNP effect is zero, the power between the 2dfLRT (solid red line) and the SNP effect over time interpreted at alpha level 0.025 (dotted red line) are very similar. Comparing column 4 with column 6 in Table 2 for the set of observations where β2 is zero (first 6 rows) also demonstrates this point. Even if the effect is interpreted at alpha level of 0.05, which we do not recommend due to the concern for inflated type I error, the joint tests are only slightly less powerful. The green and blue lines from Figure 3 show the comparison between the 2dfLRT (solid lines) and single degree of freedom tests when the SNP effect is modest or strong. Here, the 2dfLRT is overwhelmingly more powerful, given that this test derives its power from both terms. This shows that a power gain can be realized by using information from the full trajectory compared to evaluating the SNP effect by itself. Table 2 also shows this point. For example, when the generating effect size for β2 is set to 0.40, power to detect a significant effect for β2 is only about 30%. Similarly, when the generating effect size for β3 is set to 0.20, power is still somewhat low (66%). The joint tests at these effect sizes, however, are sufficiently powered at 83%, representing the gain in power by considering the information provided by the full trajectory. Both of the joint tests of effect, the 2dfLRT and P0.025|0.025 (dashed line), are very similar in power across the range of effect sizes, though P0.025|0.025 is slightly less powerful for moderate to strong effects (compare column 6 with column 7 in Table 2).

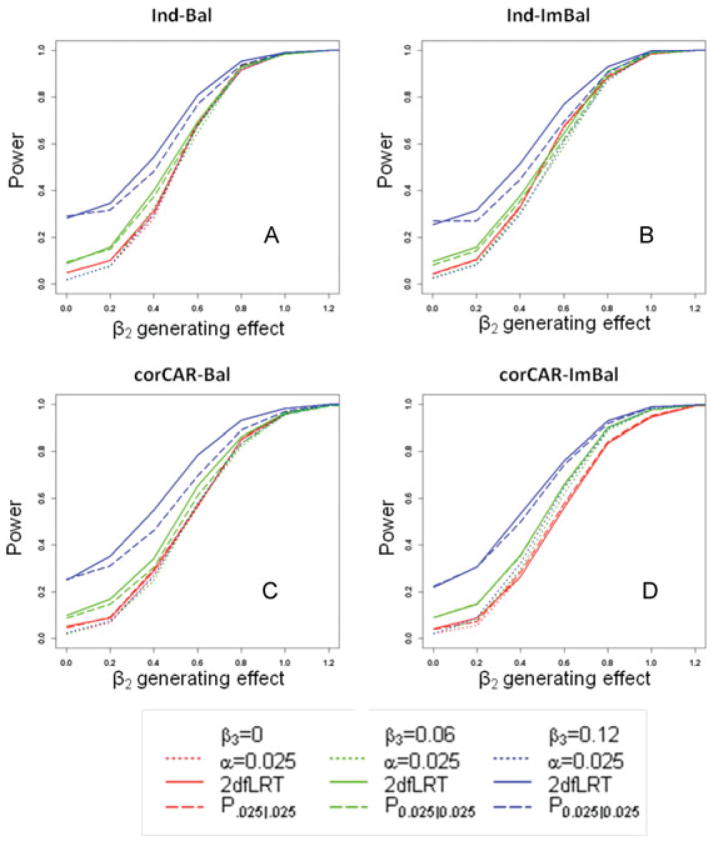

We also considered the comparison to the tests for the SNP main effect, and to do this, we looked within constant levels for the SNP effect over time. In Figure 4, when β3 is zero, the solid lines are almost identical to the dotted lines of corresponding color, indicating that the 2dfLRT is no less powerful to the single degree of freedom test for β2. It is apparent here again that increased power for the joint tests is present for moderate values of β3, and a substantial increase in power is present when β3 is large, illustrating the fact that using information across the trajectory can be more powerful, even if one or both of the SNP effects is underpowered. Compared to P0.025|0.025, the 2dfLRT is similar, but always more powerful across effect size.

Figure 4.

A–D. Each panel shows the simulated power by the SNP (β2) generating effect size. Panel A shows these calculations for the simplest case where data is balanced and the eij are independently distributed (Ind-Bal). Panel B shows the same, but the eij are distributed according to a continuous autoregressive structure of order 1 (corCAR1-Bal). Panel C shows the case where the data is imbalanced and the eij are independently distributed (Ind-ImBAL), and Panel D the most complicated cases where data is imbalanced and the eij are distributed according to a continuous autoregressive structure of order 1 (corCAR1-Imbal). Dotted lines represent power when the parameter is interpreted at alpha 0.025; solid lines represent power using the 2dfLRT. Red denotes when the change in SNP effect over time is null (β3 = 0), green denotes when the change in SNP effect over time is modest (β3 = 0.06), and blue denotes when the change in SNP effect over time is strong (β = 0.08).

Our interpretations of the power relationships for β2 and β3 remain the same for more complicated scenarios where data is imbalanced (Ind-ImBal, Figs. 3B and 4B) or the correlation structure of the within subject errors follows a continuous autoregressive structure (corCAR-Bal, Figs. 3C and 4C). We do see the power gain for the joint tests dampening somewhat compared to the single degree of freedom test when the data is both imbalanced and corCAR1 (corCAR-ImBal, Figs. 3D and 4D), however, the joint tests still represent a more powerful strategy.

We also investigated the power relationships using parameter values from the African American cohort, which afforded an opportunity to learn whether findings were similar in a new context where the variance components and their relative magnitudes differed from the white cohort. For the AAs, the variance for the intercepts between individuals (σ200) is much larger, the variance for the slopes between individuals is smaller (σ211), and the variance within individuals (σ2e) is similar to the white cohort (see Table 1). It was thus not surprising to observe that power for the SNP effect in AAs is decreased, and power for the SNP effect over time is increased compared to Whites, since the variability for intercepts is more and variability for slopes is less in the AA cohort. Despite this, although there were some slight differences, Supporting Information Table I shows that relative findings are quite similar between the two cohorts. The main difference here is that the P0.025|0.025 is slightly more powerful than the 2dfLRT in some cases, rather than less powerful as observed in the White cohort.

The power relationships we found for a minor allele frequency of 0.20 were also found at lower minor allele frequencies, although overall power was, not surprisingly, reduced at these lower frequencies. Supporting Information Figure 1 and 2 provide the power results at different minor allele frequencies for the SNP effect over time and the SNP main effect. It is clear that for low allele frequencies of 5% or less, power to detect change over time for a single rare SNP is very low, so that the strategy of combining information from the SNP main effect in this situation is particularly advantageous.

Comparison of Simulation to Closed Form Solution

The above calculations for power are all based on simulation, because the distribution of time for imbalanced data is not reflected in the closed form solution; it is known that the spacing between measurement times can influence power. The closed form solution also does not acknowledge specific structures for the residual errors. We wanted to know, at least for the single degree of freedom tests, whether the closed form solutions were very different from our simulated power, especially for the case where data is imbalanced and the within subject errors are distributed according to a continuous autoregressive structure. Table 3 presents these power calculations side-by-side for comparison where the minor allele frequency is 0.20. The closed form solution yields similar findings compared to all of our simulations, and is most closely aligned with the balanced scenarios. Very little power loss occurs when the data is imbalanced, or when the error structures are distributed corCAR1, though for the latter, closed form power calculations are slightly inflated.

Table 3.

Comparison of simulated with closed form power calculations. Closed form solutions to obtain power for a LME model make assumptions that are usually not met in real datasets, presumably necessitating simulation get an accurate estimate of power. Here, we compare power using simulation with that of a closed form solution that assumes perfect balance (time observed annually over 10 years of follow up), independently distributed residual errors (eij). This comparison illustrates whether failure to meet these assumptions results in very different power estimates. For all data show, the minor allele frequency (MAF) is set to 0.20 and the assumed alpha level is 0.025

| Closed form | Simulated

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ind-Bal | corCAR1-Bal | Ind-ImBal | corCAR1-ImBal | ||

| βsnp, βsnp_time = 0 | |||||

| 0.2 | 0.1115 | 0.076 | 0.085 | 0.068 | 0.057 |

| 0.4 | 0.4219 | 0.28 | 0.324 | 0.274 | 0.266 |

| 0.6 | 0.7952 | 0.686 | 0.667 | 0.563 | 0.566 |

| 0.8 | 0.9675 | 0.93 | 0.888 | 0.851 | 0.836 |

| 1.0 | 0.9979 | 0.989 | 0.986 | 0.961 | 0.949 |

| 1.2 | 0.9999 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.995 | 0.995 |

| 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.999 |

| βsnp_time, βsnp = 0 | |||||

| 0.02 | 0.0239 | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.03 | 0.021 |

| 0.04 | 0.043 | 0.044 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.039 |

| 0.06 | 0.0728 | 0.078 | 0.057 | 0.072 | 0.069 |

| 0.08 | 0.1162 | 0.119 | 0.107 | 0.109 | 0.112 |

| 0.10 | 0.1755 | 0.195 | 0.151 | 0.176 | 0.172 |

| 0.12 | 0.2511 | 0.279 | 0.25 | 0.232 | 0.205 |

| 0.14 | 0.341 | 0.343 | 0.274 | 0.334 | 0.302 |

| 0.16 | 0.4411 | 0.456 | 0.392 | 0.439 | 0.39 |

| 0.18 | 0.5451 | 0.529 | 0.514 | 0.516 | 0.473 |

| 0.20 | 0.6461 | 0.65 | 0.602 | 0.636 | 0.531 |

| 0.22 | 0.7377 | 0.744 | 0.671 | 0.74 | 0.664 |

| 0.24 | 0.8153 | 0.836 | 0.759 | 0.824 | 0.764 |

Discussion

In the current study, we simulate a longitudinal cognitive trait to explore the power and type I error relationships between single degree of freedom and joint tests, including a two degree of freedom likelihood ratio test. We observe that strategies of joint testing of both the SNP main effect and the SNP effect over time can properly control type I error while often providing better power under an alternative. This is because, when SNP baseline or change effects are nonzero but underpowered, joint tests allow nonsignificant parameters to contribute to the test statistic. In contrast, the consideration of a single parameter one-at-a-time, as is often done, does not incorporate subtle information contained in the trajectory. This is not the case universally, however, because when a baseline effect is very strong, and the other is not, a test of the single parameter can be more powerful as it is not weakened by the underpowered effect. Even in this case, however, power loss for the joint test is minimal. While this may not be surprising for statisticians, it is often forgotten in the context of LME modeling on the genome-wide level.

Our findings suggest that examining SNP and SNP over time effects in the same study at the accepted genome-wide level is equivalent to evaluating the minimum P-value between these two terms at each SNP, and show that the family-wide error rate for such a strategy is inflated both at the genome-wide level and for individual SNPs. This is intuitive, because if the two SNP parameters in equation (2) are uncorrelated, as we have simulated here, the number of tests for a genome-wide scan will double so that the opportunity for calling a false positive should double as well. This should also be true in the presence of correlation between the SNP main effect and the SNP effect over time, because situations where one effect is falsely positive will result in the other term being falsely positive as well. We confirmed this latter point by simulating type I error for increasing correlation between β2 and β3 and find that type I error remains very similar to our observations where no correlation was modeled, and does not increase with increasing correlation (data not shown). Most of our known data examples for trajectories of older adults show little correlation between β2 and β3, but this may be different for other examples, for instance, growth trajectories in children.

Based on our collective findings, we expect that in the context of a full-scale genome-wide study, the false-positive rate would exceed the accepted 5 × 10−8 value [Risch and Merikangas, 1996] without some adjustment procedure. We then set out to investigate what adjustment strategy would help to preserve the type I error at the genome-wide level while maximizing power. To answer this question, we considered a joint approach where both the SNP effect over time is interpreted at the alpha 0.05 level, and the SNP main effect is interpreted at an adjusted level of 0.025. Our calculation for this family-wide error rate, FWER0.05|0.025, of 0.075 suggests that it would be potentially inflated, and thus this strategy should be avoided. The only remaining acceptable strategies, then, are to employ the 2dfLRT or to interpret both SNP terms at an adjusted alpha level (P0.025|0.025), because these strategies have an acceptable type I error (0.049 for both).

We observe that for the SNP effect over time, when the SNP main effect is zero, power under the alternative is very similar no matter what strategies were considered for determining a significant SNP “hit.” This suggests that the addition of a second degree of freedom for the 2dfLRT does not result in a large penalty. As mentioned previously, when both the SNP effect over time and the SNP main effect are nonzero, the strategies that jointly test both SNP terms, the 2dfLRT and P0.025|0.025, are always more powerful because the test statistic is increased by a contribution from both terms. In particular for the SNP main effect, the 2dfLRT appeared to be slightly more powerful compared to P0.025|0.025 for the parameters we simulated in this study.

Our findings are similar to Kraft et al. [2007], who calculated power using closed form solutions for a nested case–control design where the tests of interest involved a gene effect, an effect of environment, or both. Their results suggested that power loss was minimal for a 2dfLRT when only a single effect was present and that power gains were realized when both effects were present. In the context of longitudinal data analysis with LMEs models, our findings similarly show that in scenarios of very modest, underpowered effect sizes for both parameters, a power gain is to be expected by the 2dfLRT. Particularly when using a hypothesis free design, the 2dfLRT presents a very reasonable choice to maximize power or, in some situations, to minimize power loss, while still maintaining an acceptable type I error. This general finding for power, moreover, persists across a range of minor allele frequencies, but it should be noted that power to detect SNP effects over time for minor allele frequencies <5% is very low. Thus, large sample sizes, most likely from metaanalysis, would be needed to uncover effects, and even these efforts are most likely only suitable for the detection of common variation. Our point of coupling the effect over time with the main SNP effect by using a joint test to improve power has the greatest potential impact when the variant is rare. Further to this point, strategies for multilocus tests or burden tests for rare variants may be more powerful in identifying genetic regions of interest compared to single SNP tests. Future work for haplotype tests will need to properly incorporate phase information while rare variant burden tests may consider the careful use of weight functions to incorporate functional or allele frequency information into the test statistic.

To our knowledge, only one previous publication has reported findings for a genome-wide scan employing LMEs models [Smith et al., 2010], although many GWA consortium are currently analyzing such data and expect to publish in the near future. Smith et al. employed the standard genome-wide threshold used in cross-sectional studies for a single time point to interpret the fixed parameters for both the SNP main effect as well as the SNP effect over time in their discovery cohort, and relied on replication in a second cohort to decide whether the discovery signals were in fact true positives. We note that almost no signals were replicated in the second stage, suggesting many false positives in the discovery sample, which supports our claim that the inflation of the type I error rate is of concern. Relying on replication in the second stage as conducted by Smith et al. is another alternative to what we suggest here, although interpreting tests for each parameter separately could result in a power loss for some truly causal SNPs.

Because LMEs models are so flexible, it is not possible to explore all the potential scenarios that may be encountered in real data. Our simulation did not explore how the power relationships change in the presence of nonlinear patterns over time, although we expect results to remain meaningfully the same in spite of added degrees of freedom. Other data examples will have very different variance components that will certainly influence the power calculations. Our example reflects a rather large variance for the random intercepts and the within subject variances, and they are about equal to each other. Many other examples will reflect within individual variance that is reduced compared to the between individual variance. Our investigation of the African American cohort explores such as scenario and yielded similar findings; here, the variance of the intercepts was about three times larger than the between subject variance. In addition to the African American cohort, we did explore power comparisons for other traits in different study populations and came to similar conclusions about the power relationships between the single and two degree of freedom tests (data not shown). We cannot, however, rule out that relative findings may be context dependent. We also did not consider scenarios where the SNP effect over time is not constant. In this case, evaluating a SNP effect across the trajectory many not prove to be more informative unless a more hypothesis-oriented model that allows different SNPs to exert influences at different times across the trajectory can be modeled.

We also find that closed form solutions for power do in fact reflect simulated power for the case of balanced data with independently distributed residual errors, though power is slightly inflated for the situation where a more complicated residual error structure was modeled. Because our study only considered a specific scenario, we do not recommend substituting closed form calculations for simulation in general situations, and caution researchers to consider complex error structures as well as missing observations when carrying out their power calculations.

Our study was confined to the consideration of LMEs models that are appropriate for continuously distributed traits. While it is true that for large samples the assumption of normality can be relaxed, these models are not appropriate for longitudinal binary or ordinal outcomes such as hypertension or item responses to a questionnaire. For these situations, if researchers wish to incorporate random effects, a generalized or nonlinear mixed effects model (GLME) can be employed. Our work should in principle be extendable to these models and we expect that similar power relationships for joint and single degree of freedom tests would be observed. We note, in fact, that the LME model we have simulated here can be thought of as a special case of a GLME model with an identity link function [Fizmaurice et al., 2004]. Complexities arise with use of these models for nonlinear outcomes, however, both practical and theoretical. For example, the regression coefficients for β2 and β3 have direct interpretations at the population level for a LME model and can be interpreted in the same way as a marginal model that is commonly accepted. This interpretation does not hold, however, for nonlinear data, so that careful explanation and interpretation of the estimated coefficients influencing power must be made. Thus, we encourage future work to develop guidance and power considerations for GLME models, but consider this beyond the scope of our study.

In summary, we find that joint tests properly control type I error while offering potential power gain by making use of additional information in the trajectory that may reflect a true biological signal, and consider this property especially suitable when engaging in a hypothesis-free enterprise. Based on our results, we suggest that the two degree of freedom test is an attractive analytic strategy. We also suggest that employing a family-wide calculation where the alpha level is halved is effective. We recommend either of these joint tests for genome-wide studies employing LMEs models. These findings are timely as many consortia efforts are underway to utilize the longitudinal trajectories of continuously measured traits, and may benefit by consideration of these joint tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and investigators of the Cardiovascular Health Study, which was supported by NHLBI contracts HHSN268201200036C, N01-HC-85239, N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086; N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, and NHLBI grant HL080295, with additional contribution from NINDS. Additional support was provided through AG-023629, AG-15928, AG-20098, and AG-027058 from the NIA. Kelly Benke was funded in part by the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Platform, which is supported by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute. Yan Yan Wu is a fellow of CIHR STAGE (Strategic Training for Advanced Genetic Epidemiology), which was supported by funding from Training grant GET-101831.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available in the online issue at wileyonlinelibrary.com.

References

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers KL, Cordell HJ. SNP selection in genome-wide and candidate gene studies via penalized logistic regression. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:879–891. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke KS, Carlson MC, Doan BQ, Walston JD, Xue QL, Reiner AP, Fried LP, Arking DE, Chakravarti A, Fallin MD. The association of genetic variants in interleukin-1 genes with cognition: findings from the cardiovascular health study. Exp Gerontol. 2011;46:1010–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ. 1995;310:170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PJ, Heagerty PJ, Kung-Yee Liang, Zeger SL. The Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genome wide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:227–234. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fizmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Hoboken, New Jersey: Johns Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, Furberg CD, Gardin JM, Kronmal RA, Kuller LH, Manolio TA, Mittelmark MB, Newman A, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P International Schizophrenia Consortium. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiresan S, Manning AK, Demissie S, D’Agostino RB, Surti A, Guiducci C, Gianniny L, Burtt NP, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Arnett DK, Peloso GM, Ordovas JM, Cupples LA. A genome-wide association study for blood lipid phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight J, Barnes MR, Breen G, Weale ME. Using functional annotation for the empirical determination of Bayes Factors for genome-wide association study analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft P, Yen YC, Stram DO, Morrison J, Gauderman WJ. Exploiting gene-environment interaction to detect genetic associations. Hum Hered. 2007;63:111–119. doi: 10.1159/000099183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku CS, Loy EY, Pawitan Y, Chia KS. The pursuit of genome-wide association studies: where are we now? J Hum Genet. 2010;55:195–206. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mook-Kanamori DO, Marsh JA, Warrington NM, Taal HR, Newnham JP, Beilin LJ, Lye SJ, Palmer LJ, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Pennell CE, Jaddoe VW Early Growth Genetics Consortium. Variants near CCNL1/LEKR1 and in ADCY5 and fetal growth characteristics in different trimesters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E810–E815. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly PF, Hoggart CJ, Pomyen Y, Calboli FC, Elliott P, Jarvelin MR, Coin LJ. MultiPhen: joint model of multiple phenotypes can increase discovery in GWAS. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Alonso A, Li M, Kao W, Köttgen A, Yan Y, Couper D, Boerwinkle E, Bielinski SJ, Pankow JS. Impact of repeated measures and sample selection on genome-wide association studies of fasting glucose. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:665–673. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273:1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi G, Boerwinkle E, Morrison AC, Gu CC, Chakravarti A, Rao DC. Mining gold dust under the genome wide significance level: a two-stage approach to analysis of GWAS. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:111–118. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska K, Rivadeneira F, Groenen PJ, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, Eilers PH, Lesaffre E. Fast linear mixed model computations for genome-wide association studies with longitudinal data. Stat Med. 2013;32:165–180. doi: 10.1002/sim.5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith EN, Chen W, Kahonen M, Kettunen J, Lehtimäki T, Peltonen L, Raitakari OT, Salem RM, Schork NJ, Shaw M, Srinivasan SR, Topol EJ, Viikari JS, Berenson GS, Murray SS. Longitudinal genome-wide association of cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Bogalusa heart study. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swihart BJ, Caffo B, James BD, Strand M, Schwartz BS, Punjabi NM. Lasagna plots: a saucy alternative to spaghetti plots. Epidemiology. 2010;21:621–625. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e5b06a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster RJ, Warrington NM, Weedon MN, Hattersley AT, McCaskie PA, Beilby JP, Palmer LJ, Frayling TM. The association of common genetic variants in the APOA5, LPL and GCK genes with longitudinal changes in metabolic and cardiovascular traits. Diabetologia. 2009;52:106–114. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer CJ, Mohlke KL. Finding genes and variants for lipid levels after genome-wide association analysis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:98–103. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328350fad2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte JS, Hoffmann TJ. Polygenic modeling of genome-wide association studies: an application to prostate and breast cancer. OMICS. 2011;15:393–398. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.