Abstract

Objective

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is an important extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We aimed to assess the cumulative incidence and clinical spectrum of SpA in a population-based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

Methods

The medical records of a population-based cohort of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents diagnosed with UC from 1970 through 2004 were reviewed. Patients were followed longitudinally until moving from Olmsted County, death, or June 30, 2011. We used the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria, and modified New York criteria to identify patients with spondyloarthritis.

Results

The cohort included 365 patients with UC, of whom 41.9% were women. The median age at diagnosis of UC was 38.6 years (range, 1.2-91.4). Forty patients developed spondyloarthritis based on the ASAS criteria. The cumulative incidence of a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis after an established diagnosis of UC was 4.8% at 10 years (95% CI, 2.2%-7.3%), 13.7% at 20 years (9.0%-18.1%), and 22.1% at 30 years (4.3%-29.1%).

Conclusion

The cumulative incidence of all forms of SpA increased to about 22% by 30 years from UC diagnosis. This value is slightly greater than what we previously described in a population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease diagnosed in Olmsted County over the same time period. SpA and its features are associated with UC, and heightened awareness on the part of clinicians is needed for diagnosing and managing them.

Keywords: Spondyloarthritis, ulcerative colitis, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory arthritis is one of the most common extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Musculoskeletal symptoms in general have been described in 6% to 46% of IBD patients (1), and arthropathies have been estimated to occur in 4% to 23% of all IBD patients (2). The arthropathies associated with IBD may be peripheral or axial arthropathies. The prevalence of peripheral arthropathies has been estimated in 5-20% of patients, while the axial arthropathies have been estimated to be found in 3-25% of IBD patients (1, 3, 4). While both major subtypes of IBD have an association between active bowel and joint disease, active peripheral arthropathies are more commonly associated with active UC (1).

UC has been associated with a lower prevalence of arthropathy in the literature when compared to Crohn’s disease (1, 4-6), although others have reported that there is no major difference in the occurrence of spondyloarthritis between UC and Crohn’s disease (7). Axial arthropathies, which include sacroiliitis and spondylitis, have been estimated to occur in 5-22% of patients with Crohn’s disease and 2-6% of patients with UC. In a retrospective study from 1998, the frequency of pauciarticular peripheral arthritis, which is most strongly correlated with IBD activity, was reported to be 3.6% in patients with UC and 6% in patients with Crohn’s disease (8). In contrast, another retrospective study from 2001 noted the frequency of peripheral arthritis to be 6.1% in patients with UC and 1.7% in Crohn’s disease (9).

Estimates of spondyloarthritis (SpA) prevalence in IBD are available from several cohorts, but none have been reported in US populations, and no population-based incidence estimates are available from any established cohort (1, 3, 8-13). Our aim was to assess the prevalence and cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in a population-based cohort of UC patients from Olmsted County, Minnesota. We also sought to compare these findings to the spondyloarthritis prevalence and incidence rates in patients with CD from the same population base.

METHODS

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a unique medical records linkage system developed in the 1950s and supported by the National Institutes of Health. It exploits the fact that virtually all of the health care for the residents of Olmsted County is provided by two organizations: Mayo Medical Center, consisting of Mayo Clinic and its two affiliated hospitals (Rochester Methodist and Saint Marys), and Olmsted Medical Center, consisting of a smaller multispecialty clinic and its affiliated hospital (Olmsted Community Hospital). In any four-year period, over 95% of county residents are examined at either one of the two health care systems (14). Diagnoses generated from all outpatients visits, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, nursing home visits, surgical procedures, autopsy examinations, and death certificates are recorded in a central diagnostic index. Thus, it is possible to identify virtually all diagnosed cases of a given disease for which patients sought medical attention.

The resources of the REP were used to identify a population-based cohort of patients diagnosed with UC from 1970 through 2004 (15-17). All cases of UC were diagnosed based on finding the following criteria on two occasions separated by at least six months: 1) diffusely granular or friable colonic mucosa on endoscopy; and 2) continuous mucosal involvement based on endoscopy or barium studies (16).

Approval for this study was obtained from the institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center. Data on musculoskeletal symptoms and disease beginning at birth were recorded; the patients were followed longitudinally until moving from Olmsted County, death, or June 30, 2011.

The European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) criteria, modified New York criteria, and Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria were retrospectively applied in identifying patients with spondyloarthritis (18-21). Demographic data including gender, date of birth, and date of UC diagnosis were recorded as previously described (15-17), date of arthropathy diagnosis by the treating physician, diagnosis of another primary inflammatory arthritis, family history of arthropathy, and characteristics of spondyloarthritis. These included presence of inflammatory back pain (based on physician diagnosis with medical records indicating presence of protracted back stiffness, which improved with activity), synovitis, psoriasis, nongonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, alternating buttock pain, enthesitis (Achilles tendonitis or plantar fasciitis), sacroiliitis (based on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging), which was diagnosed both clinically and radiographically, uveitis, limitation in spine motion, lumbar spine pain, limitation of chest expansion, radiographic evidence of ankylosis, HLA B-27 status, oligoarthritis and specific joints involved, or polyarthritis and specific joints involved; this information was recorded based on physician diagnosis in the medical record. The abstracted data included diagnoses of spondyloarthritis or its clinical features seen in usual practice by treating physicians, most often a primary care physician or rheumatologist. Diagnoses of uveitis and psoriasis were made by an ophthalmologist or dermatologist, respectively.

Diagnosis of specific forms of spondyloarthritis included those based on treating physician diagnosis. Following a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, all patients who had either inflammatory back pain or synovitis were included in our study as having spondyloarthritis based on the ESSG criteria since all of these patients already carried a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (18-20, 22). Patients were also included as having ankylosing spondylitis if there was evidence of either limitation in spine motion and lumbar spine pain in the setting of radiographic evidence of ankylosis based on the modified New York criteria for this disease (21). Finally, all patients who had arthritis, enthesitis, or dactylitis were included in our study as having spondyloarthritis based on the ASAS criteria since all of these patients already carried a diagnosis of UC (19, 20).

In addition to including treating physician diagnoses of spondyloarthritis, we searched individual medical records for features of this disease even when a formal diagnosis was not made; those with features of spondyloarthritis that correlated with either the ESSG or the ASAS criteria were included as having this diagnosis.

The cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis after UC diagnosis was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) for the observed proportions (%) were based on the exact binomial distribution. The prevalences of psoriasis, nongonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, alternating buttock pain, enthesitis, sacroiliitis, uveitis, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, oligoarthritis, and polyarthritis were also calculated.

RESULTS

Incidence

A total of 366 patients with UC were identified. One patient denied research authorization and therefore our UC cohort consisted of 365 patients, of whom 41.9% were women, and the median age at diagnosis of UC was 35.6 years (range, 1.2-91.4 years) (Table 1). Prior to UC diagnosis, there were 3 patients from the total cohort who had a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis based on ESSG criteria, and therefore the pre-UC prevalence of spondyloarthritis was 0.8% (95% CI, 0.2%-2.4%); no patients carried a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. Based on the ASAS criteria, 14 patients from the total of 365 patients with UC had been diagnosed with spondyloarthritis prior to a diagnosis of UC; therefore, the prevalence of spondyloarthritis based on ASAS criteria prior to UC was 3.8% (95% CI, 2.1%-6.4%). The median interval between spondyloarthritis diagnosis and UC diagnosis was 3.5 years (range, 0.3-12.7 years). These patients were excluded from the analysis of arthritis incidence subsequent to UC diagnosis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 365 residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota diagnosed with ulcerative colitis between 1970 and 2004.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 212 (58.1) |

| Female | 153 (41.9) |

| Age at Diagnosis | |

| <18 years | 26 (7.1) |

| 18-39 years | 190 (52.0) |

| 40-59 years | 102 (28.0) |

| ≥ 60 years | 47 (12.9) |

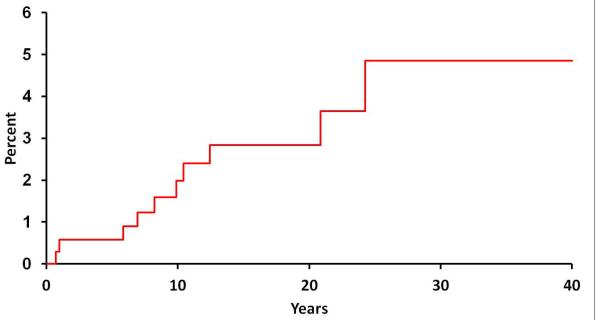

Following the incident date of UC diagnosis, 10 of 362 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis according to the ESSG criteria. The cumulative incidence of a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis after an established diagnosis of UC was 1.9% at 10 years (95% CI, 0.4%-3.6%), 2.8% at 20 years (0.9%-4.8%), and 4.9% at 30 years (1.4%-8.2%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence (1 minus survival free) of any spondyloarthropathy (based on European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group criteria) from ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosis among 365 Olmsted County, Minnesota residents with UC (1970-2004).

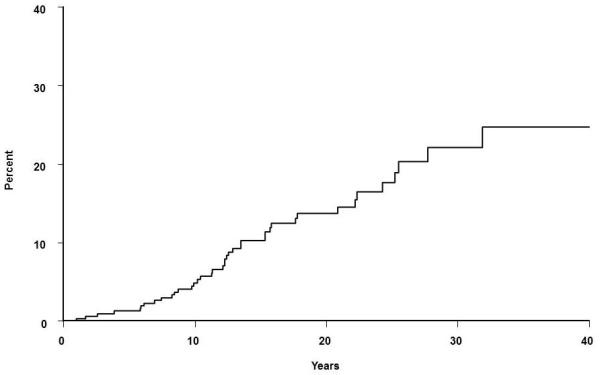

According to the ASAS criteria, 40 of 351 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis following a diagnosis of UC. The cumulative incidence of a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis after an established diagnosis of UC was 4.8% (95% CI, 2.2%-7.3%) at 10 years, 13.7% (9.0%-18.1%) at 20 years, and 22.1% (4.3%-29.1%) at 30 years (Figure 2). The median interval between UC diagnosis and spondyloarthritis diagnosis was 12.3 years (range, 1-31.9 years).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence (1 minus survival free) of any spondyloarthritis (based on Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society classification criteria) from ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosis among 351 Olmsted County, Minnesota residents with UC (1970-2004).

Of the total 13 patients diagnosed with spondyloarthritis using the ESSG criteria, 8 patients (61.5%) were female and 5 patients (38.5%) were male. Of the total 54 patients diagnosed with spondyloarthritis using the ASAS criteria, 27 patients (50%) were female and 27 patients (50%) were male.

Subtypes of Spondyloarthropathy

Based on the modified New York criteria, ankylosing spondylitis was diagnosed in 1 of 365 patients after UC diagnosis. The 10-year cumulative incidence of ankylosing spondylitis was 0.3% (95% CI, 0-0.9%), while both the 20-year and 30-year cumulative incidences remained the same. There were no physician diagnoses of reactive, psoriatic, or undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy found in our cohort.

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical features of spondyloarthritis identified in the cohort of 365 patients are shown in Table 2. In the pre-UC diagnosis period, disease features and frequencies included psoriasis (0.8%), urethritis/cervicitis (0.3%), buttock pain (0.8%), plantar fasciitis (0.5%), uveitis (0.5%), oligoarthritis (0.5%) and polyarthritis (0.3%). In the post-UC diagnosis period, the frequency of spondyloarthritis disease features in UC patients were: sacroiliitis, 1.7%; oligoarthritis, 3.4%; and polyarthritis, 0.5%. The frequencies of other extraintestinal disease manifestations occurring following the diagnosis of UC were: psoriasis, 1.7%; alternating buttock pain, 1.4%; plantar fasciitis, 6.3%; Achilles tendonitis, 1.4%; and uveitis, 2.8%.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of spondylarthritis in the 365 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota (1970-2004).

| Spondyloarthropathy Feature |

Features Present Prior to UC Diagnosis, N (%) |

Features Appearing After UC Diagnosis, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.7) |

| Urethritis/Cervicitis | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Buttock Pain | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) |

| Plantar Fasciitis | 2 (0.5) | 22 (6.3) |

| Achilles tendonitis | 0 (0) | 5 (1.4) |

| Sacroiliitis | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) |

| Uveitis | 2 (0.5) | 10 (2.8) |

| Oligoarthritis | 2 (0.5) | 12 (3.4) |

| Polyarthritis | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

DISCUSSION

The major aim of this study was to define the incidence and clinical features of spondyloarthritis in a population-based cohort of patients with UC. We found that the incidence of spondyloarthropathy increased to about 22% by 30 years from UC diagnosis (Figure 2). The incidence of ankylosing spondylitis, on the other hand, was much lower with a cumulative incidence of 0.3% at 30 years from UC diagnosis.

Using the ESSG criteria, the cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in this UC cohort was about half of the value detected in a population-based Crohn’s disease cohort diagnosed over the same time period. In the Crohn’s disease cohort, we had found the cumulative incidence of spondyloarthropathy was approximately 10% by 30 years after Crohn’s disease diagnosis (22). The cumulative incidence of ankylosing spondylitis, specifically, was 0.5% at 30 years from Crohn’s disease diagnosis, and this finding was relatively similar to that of our UC cohort (22).

In contrast, based on the ASAS criteria, we found a higher cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in our UC cohort at 30 years compared to that of our Crohn’s disease cohort (22). Specifically, the 30 year cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in UC was 22% compared with the 19% cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis found in our Crohn’s disease cohort. These higher rates may in part be due to the increased sensitivity of the ASAS criteria for diagnosing spondyloarthritis when compared to the ESSG criteria. Also, the frequencies of plantar fasciitis and oligoarthritis were higher in our UC cohort (6.3% and 3.4%, respectively) compared to our Crohn’s disease cohort (3.9% and 2.9%, respectively)(22). The ASAS criteria employ both of these features to classify spondyloarthritis, and hence a higher rate of spondyloarthritis was detected in our UC cohort. This finding is in contrast to the current literature that suggests a lower rate of spondyloarthritis in UC compared to Crohn’s disease (1, 4, 5). Since active joint symptoms are generally reported to be more frequent in active UC compared to active Crohn’s disease, it is possible that more patients with active UC were presenting for evaluation and were concomitantly diagnosed with arthritis. Also, even though the specificity of the ASAS criteria is higher than that of the ESSG criteria (84.4% versus 65.1%), it may not be specific enough to capture diagnoses of pure spondyloarthritis. (19, 20).

Similar to what we had found in our Crohn’s disease cohort, the frequency of features of spondyloarthritis increased from the pre-UC diagnosis period to the post-UC diagnosis period (Table 2). Plantar fasciitis and psoriasis were equally the most common features prior to UC diagnosis, but plantar fasciitis alone was the most common feature after a diagnosis of UC. The diagnoses of psoriasis, plantar fasciitis, uveitis, oligoarthritis, Achilles tendonitis, and sacroiliitis more than doubled between the pre- and post-UC diagnosis periods. The majority of our cohort had pauciarticular, or Type 1, arthritis (Table 2).

Salvarani, et al. reported a similar frequency of spondyloarthritis (based on ESSG criteria) in UC and Crohn’s disease, which is in contrast to our findings that the incidence rate of spondyloarthritis (based on ESSG criteria) in UC is about half the rate of that in Crohn’s disease (9). Also, in contrast to our study, they found a higher frequency of enthesopathy in Crohn’s disease compared that that in UC. While their study only included 3 years of patient information and primarily data on prevalence of musculoskeletal manifestations, ours is a true incidence study with more than 30 years of patient follow-up.

The frequencies of uveitis and arthritis in our UC cohort were lower when compared to that of the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort study, which examined all extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease patients based on questionnaires completed by treating physicians (23). Uveitis and arthritis were found in 3.8% and 21.3%, respectively, of UC patients in the Swiss study, while we found those frequencies were 3.4% (oligoarthritis), 0.5% (polyarthritis), and 2.8% (uveitis) after UC diagnosis (24). On the other hand, we found a somewhat higher frequency of UC patients with psoriasis (1.7%) compared to the Swiss cohort (0.8%) (24). Some of these differences might be explained by differences in case ascertainment methodology. While we abstracted data on arthritis from individual medical records based on internist, rheumatologist, or gastroenterologist diagnoses, the Swiss cohort relied on data gathered from questionnaires by gastroenterologists only. Similar to our study, psoriasis and uveitis were diagnosed by a dermatologist or ophthalmologist, respectively. Finally, unlike our study, the Swiss study was not a population-based cohort (23).

Inflammatory bowel disease has been noted to share an immunologic basis with psoriasis, in particular, and increased frequency of psoriasis than what was observed may have been expected (24). The overall incidence of psoriasis in Olmsted County from 1970-2000 is relatively low – 62.3 per 100,000 person-years – and this could cause the relatively low frequency of psoriasis associated with UC (25).

Our frequencies of polyarthritis, oligoarthritis, sacroiliitis, and ankylosing spondylitis were lower than those of D’Inca, et al (8). For instance, our frequency of sacroiliitis was 1.7%, while D’Inca et al found a frequency of 2.1% (8). Their data was obtained through patient questionnaire and rheumatology evaluation, including a total body bone scintigraphy scan. However, our study was based on medical record review of community-based medicine practices, where not all patients are evaluated by rheumatologists and not all undergo extensive testing.

A population-based study from Norway conducted by Palm and colleagues reported the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis as 2.6% in UC and overall spondyloarthropathy as 20% in UC patients (10). In part, their data were obtained by physician and patient questionnaire, while ours was based on individual medical record review.

The strength of this study lies in the use of the Rochester Epidemiology Project population-based patient capture and up to 30 years of follow-up. Also, data were ascertained based on individual medical records and physician-based diagnoses rather than, for instance, ICD-9 codes. Since this study was conducted in a usual medical practice, where not all patients were evaluated by a rheumatologist, some diagnoses of spondyloarthritis features may have been missed. Primary care physicians likely would not have undertaken rheumatologic classification criteria for spondyloarthropathy, thereby potentially leading to under-diagnosis due in part to difficulty making diagnoses such as inflammatory back pain, which is a required component of the ESSG criteria. However, this study is a population-based study of patients not routinely undergoing subspecialty evaluation, so our estimates of spondyloarthritis incidence and clinical features can be considered to be the minimum rates in the general population.

Ankylosing spondylitis is the most recognized form of spondyloarthritis in the general community. Since we could not reliably evaluate reactive or psoriatic spondyloarthritis in our UC cohort, these diagnoses were not included in our analysis. Also, HLA-B27 determinations were not routinely made in our clinical practice and thus were available for only a few patients in our cohort; this has not been included in our results due to the limited data.

In summary, we have for the first time defined the cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in a population-based cohort of UC patients using complete medical record information. This study shows that the cumulative incidence and features of spondyloarthritis increase from time of UC diagnosis. We have shown that the incidence rate of spondyloarthropathy in UC may be higher than that of Crohn’s disease. Physicians need to maintain a high level of suspicion for this extraintestinal manifestation. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the reasons for higher rates of spondyloarthritis and its clinical features in UC compared to CD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Journal of Rheumatology following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version (Shivashankar R, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Matteson EL. Incidence of spondyloarthropathy in patients with ulcerative colitis: a population-based study. J Rheumatol 2013;40(7):1153-1157) is available online at: http://jrheum.org/content/40/7/1153.full.

Supported in part by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education & Research, and made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant number R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging).

Footnotes

Disclosures: No relevant disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourikas LA, Papadakis KA. Musculoskeletal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Dec;15(12):1915–24. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Inca R, Podswiadek M, Ferronato A, Punzi L, Salvagnini M, Sturniolo GC. Articular manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2009 Aug;41(8):565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardizzone S, Puttini PS, Cassinotti A, Porro GB. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008 Jul;40(Suppl 2):S253–9. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(08)60534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr;96(4):1116–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jose FA, Garnett EA, Vittinghoff E, Ferry GD, Winter HS, Baldassano RN, et al. Development of extraintestinal manifestations in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Jan;15(1):63–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvarani C, Vlachonikolis IG, van der Heijde DM, Fornaciari G, Macchioni P, Beltrami M, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations in a population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001 Dec;36(12):1307–13. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fornaciari G, Salvarani C, Beltrami M, Macchioni P, Stockbrugger RW, Russel MG. Muscoloskeletal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001 Jun;15(6):399–403. doi: 10.1155/2001/612531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orchard TR, Wordsworth BP, Jewell DP. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998 Mar;42(3):387–91. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salvarani C, Vlachonikolis IG, van der Heijde DM, Fornaciari G, Macchioni P, Beltrami M, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations in a population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001 Dec;36(12):1307–13. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palm O, Moum B, Ongre A, Gran JT. Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population study (the IBSEN study) J Rheumatol. 2002 Mar;29(3):511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vlam K, Mielants H, Cuvelier C, De Keyser F, Veys EM, De Vos M. Spondyloarthropathy is underestimated in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and HLA association. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec;27(12):2860–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez VE, Costas PJ, Vazquez M, Alvarez G, Perez-Kraft G, Climent C, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathy in Puerto Rican patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ethn Dis. 2008 Spring;18(2 Suppl 2):S2-225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanna CC, Ferrari Mde L, Rocha SL, Nascimento E, de Carvalho MA, da Cunha AS. A cross-sectional study of 130 Brazilian patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: analysis of articular and ophthalmologic manifestations. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Apr;27(4):503–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 May 1;173(9):1059–68. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loftus EV, Jr., Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jun;114(6):1161–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr., Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007 Mar;13(3):254–61. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingle SB, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Sandborn WJ. Increasing incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2001-2004 (abstract) Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4 Suppl 2):A19–20.15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Oct;34(10):1218–27. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudwaleit M, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):770–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):777–83. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984 Apr;27(4):361–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shivashankar R, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Bongartz T, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Matteson EL. Incidence of spondyloarthropathy in patients with Crohn’s disease: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):2148–2152. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, Pittet V, Prinz Vavricka BM, Zeitz J, et al. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Jan;106(1):110–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li WQ, Han JL, Chan AT, Qureshi AA. Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and increased risk of incident Crohn’s disease in US women. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2012 Aug 31; doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Dann FJ, Gabriel SE, Maradit Kremers H. Trends in incidence of adult-onset psoriasis over three decades: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009 Mar;60(3):394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]