Abstract

Recent findings suggest that Notch-1 signaling contributes to neuronal death in ischemic stroke, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a global regulator of cellular responses to hypoxia, can interact with Notch and modulate its signaling during hypoxic stress. Here we show that Notch signaling interacts with the HIF-1α pathway in the process of ischemic neuronal death. We found that a chemical inhibitor of the Notch-activating enzyme, γ-secretase, and a HIF-1α inhibitor, protect cultured cortical neurons against ischemic stress, and combined inhibition of Notch-1 and HIF-1α further decreased neuronal death. HIF-1α and Notch intracellular domain (NICD) are co-expressed in the neuronal nucleus, and co-immunoprecipitated in cultured neurons and in brain tissue from mice subjected to focal ischemic stroke. Overexpression of NICD and HIF-1α in cultured human neural cells enhanced cell death under ischemia-like conditions, and a HIF-1α inhibitor rescued the cells. RNA interference-mediated depletion of endogenous NICD and HIF-1α also decreased cell death under ischemia-like conditions. Finally, mice treated with inhibitors of γ-secretase and HIF-1α exhibited improved outcome after focal ischemic stroke, with combined treatment being superior to individual treatments. Additional findings suggest that the NICD and HIF-1α collaborate to engage pro-inflammatory and apoptotic signaling pathways in stroke.

Keywords: apoptosis, HIF-1α, ischemic stroke, neuronal cell death, Notch

Introduction

Aging is a major risk factor for stroke, a leading cause of morbidity and death worldwide (Mukherjee and Patil, 2011). The cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the degeneration and death of neurons affected in stroke are poorly understood, but involve oxidative stress, a neuronal energy deficit, inflammation and a form of programmed cell death called apoptosis (Hou and MacManus, 2002; Broughton et al., 2009; Sims and Muyderman, 2010 for review). Notch-1 (Notch) signaling plays a crucial role in all phases of brain development; it regulates the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells, and influences cell survival and synaptic plasticity. In addition, there is increasing evidence that Notch pathways are important in neuropathological events including inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) disease, brain and spinal cord trauma, and ischemic stroke (Arumugam et al., 2006; 2011; Yuan and Yu, 2010; Dias et al., 2012; Park et al., 2013). We previously reported that activity of γ-secretase, and resulting Notch activation, are elevated in cultured primary cortical neurons subjected to ischemia-like conditions consisting of 3-6 h of oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) (Arumugam et al., 2006). We also found that γ-secretase activity is elevated in ischemic brain tissue in a mouse model of focal ischemic stroke (Arumugam et al., 2006). It was also shown that Notch signaling may interact with hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) to contribute to injury outcome following hypoxic conditions (Zheng et al., 2008).

Hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a transcription factor responsible for cellular and tissue adaptation to low oxygen tension. HIF-1 is a heterodimer consisting of a constitutively expressed β subunit and an oxygen-regulated α subunit, which primarily determines HIF-1 activation, and regulates a series of genes that participate in angiogenesis, iron and glucose metabolism and cell proliferation and survival (Shi, 2009; Singh et al., 2012). HIF-1 responds to reduced oxygen levels in the brain after cerebral ischemia. Systemic hypoxia rapidly increases the nuclear content of HIF-1α in mouse brains (Stroka et al., 2001; Bernaudin et al., 2002). Furthermore, HIF-1α expression is induced in the brain following focal ischemia (Bergeron et al., 1999), with HIF-1α levels diminishing gradually from the ischemic core to more distant regions (Demougeot et al., 2004). Both neuroprotective and detrimental effects of HIF-1 have been reported in experimental models of ischemic stroke (Helton et al., 2005; Baranova et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2007; Shi, 2009; Xin et al., 2011), including in neuron-specific HIF-1α deficient mice. One study reported that neuron-specific knockdown of HIF-1α resulted in increased tissue damage and reduced survival rate following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), suggesting a neuroprotective effect of HIF-1α (Baranova et al., 2007). In contrast, in other studies inhibition or deletion of HIF-1α resulted in reduced damage following ischemic stroke or hypoxic conditions, indicating a detrimental effect of HIF-1α (Helton et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2009). Other studies have shown HIF-1α to play a role in hypoxic preconditioning, a process in which mild stress prior to a stroke is neuroprotective (Liu et al., 2005). Taken together, these observations might suggest the possibility that HIF-1α can induce cell death in severe and protracted ischemia, but promote cell survival when activated prior to stroke and during mild ischemic stress. Another recent study provided a mechanistic paradigm for HIF-1α and Notch interaction in Drosophila that may also be present in mammals, involving a ligand-independent mechanism for hemocyte survival during both normal development and hypoxic stress (Mukherjee et al., 2011). Furthermore, recent evidence showed that HIF-1α-induced activation of the Notch pathway is essential for hypoxia-mediated maintenance of glioblastoma stem cells (Qiang et al., 2012). Whether the interaction between Notch and HIF-1α by ischemia leads to neuronal cell death or survival and attendant transcriptional activity is unknown. In the present study we provide evidence that Notch and HIF-1α collaborate in the activation of apoptotic, pro-inflammatory, and neurodegenerative pathways during brain injury following ischemia-reperfusion.

Material and Methods

Primary Cortical Neuronal Cultures

Dissociated cell cultures of mouse cortex were established from day 16 C57B/6J mouse embryos, as previously described (Okun et al., 2007). Cells were plated in 35, 60 or 100-mm diameter polyethylenimine-coated plastic dishes and maintained at 37 °C in Neurobasal medium containing 25 mM of glucose and B-27 supplement (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.001 % gentamycin sulfate and 1 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Approximately 95% of the cells in such cultures were neurons and the remaining cells were astrocytes.

Pharmaceuticals

γ-secretase inhibitor XXI (Compound E) was purchased form Merck Calbiochem (565790), HIF-1α inhibitor 2ME2 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (M6383), and HIF-1α stabilizer (DMOG) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (D3695). Primary neuronal cultures were subjected to glucose deprivation or oxygen and glucose deprivation at 7 days after plating, together with pharmaceutical treatment at the stated concentrations. For NICD and/or HIF-1α -transfected SY5Y cultures, OGD experiments were conducted 24 h after transfection, accompanied by the treatment with 2ME2.

Glucose Deprivation and Oxygen Glucose Deprivation

For glucose deprivation (GD), glucose-free Locke’s buffer containing (in mmol/L) 154 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 2.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 3.6 NaHCO3, 5 HEPES (pH 7.2) and 5 mg/L gentamycin was used. For GD, cultured neurons were incubated with glucose-free Locke’s buffer for 6, 12 or 24 h. For combined oxygen and glucose deprivation, neurons were incubated in GD medium in an oxygen-free chamber for 1, 3 and 8 hrs.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide (10%) gel electrophoresis using a Tris-glycine running buffer. Gels were then electro-blotted using a transfer apparatus (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer containing 0.025 mol/L Tris base, 0.15 mol/L glycine, and 10% (v/v) methanol for 1.5 h at 15 V onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was then incubated in blocking buffer (5% non-fat milk in 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 0.2 % Tween-20) for 1 h at 23°C. The membrane was then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies including those that selectively bind cleaved Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling), NICD (Abcam), HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals), phosphorylated p65 (Ser536; Cell Signaling), Notch-1 (Santa Cruz), phospho JNK (Cell Signaling), total JNK (Cell Signaling), and actin (Sigma). After washing three times (5 min per wash) with Tris-buffered saline-T (20 mmol/L Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 0.2% Tween-20), the membrane was incubated with a horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. After washing five times (5 min per wash) with Tris-buffered saline, the membrane was incubated with chemiluminescent substrate for enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce Endogen) for 5 min, and chemiluminescent signals were visualized by exposing the membrane to x-ray film (Kodak x-ray film; InterScience).

Immunocytochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Coverslips containing cortical neurons subjected either to normal Neurobasal medium or GD medium were fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich). Fixed cells were permeabilized and incubated in blocking solution (1% BSA and 0.1% Triton-X in PBS) at room temperature for 1 h before overnight incubation at 4°C with microtubule-associated protein 2 antibody (MAP2, mouse monoclonal, Millipore) along with either HIF-1α (rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz), NICD (rabbit polyclonal, Abcam), p-p65 (Ser536; Cell signaling) diluted in blocking solution. Following incubation in primary antibody, the cells were incubated in the appropriate Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. Following secondary antibody incubation, coverslips were sealed with Vectashield mounting solution (Vector) on glass slides. For immunohistochemistry, frozen cryostat brain sections were obtained from sham surgery and stroke mice, following trans-cardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde and were immunostained with antibodies against HIF-1α (mouse monoclonal, Novus Biologicals), NICD (rabbit polyclonal, Abcam) and MAP2 (chicken monoclonal, Abcam). Imaging was performed using confocal microscopy (LSM700, Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) with a 100X oil immersion objective. Single confocal images were converted to 512 × 512 pixel 12 bit TIFF images.

Overexpression and siRNA experiments

SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium including 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin. These cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For transfections, cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105/well in six-well plates 1 day before transfection. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then incubated with complete medium for 24 hrs. NICD construct was kindly provided by Dr. B. A. Osborne (University of Massachusetts; Shin et al., 2006) and the FLAG-tagged full-length HIF-1α was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified full-length HIF-1α fragment into the KpnI/BamHI site of p3XFLAG-7.1 (Sigma). For siRNA experiments, 5 days old primary cortical neurons were used and both Notch-1 siRNA and HIF-1α siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz.

Cell viability assays

Cell viability was determined by the Trypan blue exclusion assay. For the transfected SH-SY5Y cells, cell viability was determined based on the morphology of GFP-positive cells under a fluorescence microscope.

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion and Reperfusion

Three-month-old C57BL/6J male mice were used for in vivo experiments. The focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion model was similar to that described previously (Arumugam et al. 2004). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with isofluorane, a midline incision was made in the neck, and the left external carotid and pterygopalatine arteries were isolated and ligated with 5-0 silk thread. The internal carotid artery (ICA) was occluded at the peripheral site of the bifurcation of the ICA and the pterygopalatine artery with a small clip, and the common carotid artery (CCA) was ligated with 6-0 silk thread. The external carotid artery (ECA) was cut, and a 6-0 nylon monofilament with a tip that was blunted (0.2–0.22 mm) using a coagulator was inserted into the ECA. After the clip at the ICA was removed, the nylon thread was advanced into the middle cerebral artery (MCA) until light resistance was felt. The nylon thread and the CCA ligature were removed after 1 h of occlusion to initiate reperfusion. In the sham group, these arteries were visualized but not disturbed. Mice were administered either 1 mg/kg compound E (Merck), 20 mg/kg 2ME2 (Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle (DMSO) by infusion into the femoral vein (20 μL) immediately after the ischemic period. Cerebral blood flow was measured by placing the animal’s head in a fixed frame after it had been anesthetized and prepared for surgery. A craniotomy was performed to access the left middle cerebral artery and was extended to allow positioning of a 0.5-mm Doppler probe (Moor LAB, Moor Instruments) over the underlying parietal cortex approximately 1 mm posterior to bregma and 1 mm lateral to the midline. The University of Queensland Animal Care and Use Committee approved these procedures.

Neurological Assessment

The functional consequences of focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) injury were evaluated using a 5-point neurological deficit score (0, no deficit; 1, failure to extend right paw; 2, circling to the right; 3, falling to the right; and 4, unable to walk spontaneously) and were assessed in a blinded fashion.

Quantification of Cerebral Infarction

Following 72 h of reperfusion, the mice were euthanized with a lethal dose of isoflurane. The brains were immediately removed and placed into PBS (4 °C) for 15 min, and 2-mm coronal sections were cut with a tissue cutter. The brain sections were stained with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) in phosphate buffer at 37°C for 15 min. The stained sections were photographed, and the digitized images were used for analysis. The borders of the infarct in each brain slice were outlined and the area quantified using NIH image 6.1 software (National Institutes of Health, USA). To correct for brain swelling, the infarct area was determined by subtracting the area of undamaged tissue in the left hemisphere from that of the intact contralateral hemisphere. Infarct volume was calculated by integration of infarct areas for all slices of each brain in a blinded manner, and was expressed as a % of the ipsilateral hemisphere.

Data Analysis

All the results are reported as the means ± S.E.M. The overall significance of the data was examined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The differences between the groups were considered significant at P<0.05 with the appropriate Bonferroni correction made for multiple comparisons. Neurological behavior scores were analyzed by using a nonparametric Kruska–Wallis test and Dunn’s Multiple Comparison Test.

Results

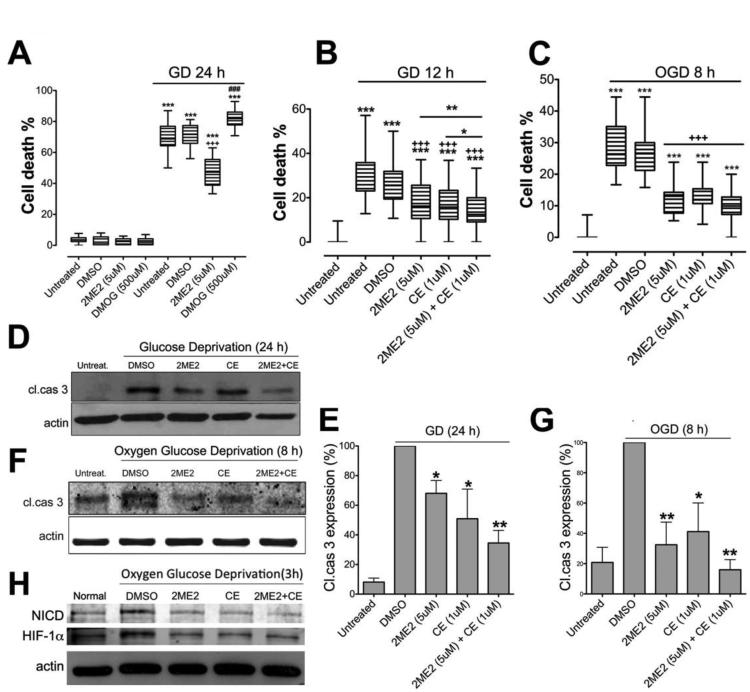

Inhibition of HIF-1α/and γ-secretase reduces neuronal death during ischemia-like conditions

We first investigated the effects of the cell-permeable HIF-1α inhibitor 2-methoxyestradiol (2ME2) which is a competitive inhibitor of HIF-1α prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PH) (Chen et al., 2008), and the HIF-1α inducer DMOG (Zhou et al., 2006), against ischemic stroke-like cell death in mouse primary cortical neurons. We subjected 7-10 days old cortical neurons to glucose deprivation (GD) in the presence of 2ME2 or DMOG. GD-induced cell death was attenuated by 2ME2 (5 μM) and increased by DMOG (500 μM) (Fig. 1A). We previously showed that the γ-secretase inhibitors N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) and (S,S)- 2-[2-(3,5-difluorophenyl)-acetylamino]-N-(1-methyl-2-oxo-5-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H benzo[e][1,4]diazepin-3-yl)-propionamide (Compound E; CE), decreased primary neuronal cell death during GD, or combined oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) (Arumugam et al., 2006; Arumugam et al., 2011). Here, CE (1 μM) also decreased death of primary cortical neurons under both GD and OGD conditions (Fig. 1B, C). Moreover, combined HIF-1α and γ-secretase inhibition with 2ME2 and CE, respectively, provided enhanced protection against cell death compared to either CE or 2ME2 alone following GD (Fig. 1B). We next analyzed levels of cleaved caspase-3, the active form of an apoptotic protease, following GD or OGD. Treatment with either 2ME2 or CE reduced cleaved caspase-3 levels compared to vehicle treatment under either GD or OGD conditions (Fig. 1D,E,F,G). Furthermore, combined 2ME2/CE treatment was more effective than either single treatment in reducing cleaved caspase-3 during GD and OGD (Fig. 1D,E,F,G). Both NICD and HIF-1α were elevated following OGD condition and reduced by treatment with CE and 2ME2 respectably (Fig. 1 H).

Figure 1. Inhibition of NICD and HIF-1α protects cultured cortical neurons against death under ischemia-like conditions.

(A) Treatment with 2ME2 significantly reduced cell death, and treatment with DMOG increased cell death, under GD condition. n=6, ***p< 0.005 compared with the vehicle-treated group under normal culture conditions; +++, ###p<0.005 compared with the vehicle treated group under GD condition. (B) Compound E and 2ME2 each significantly reduced GD-induced cell death, and combined treatment further reduced cell death during GD. n=6, ***p<0.005 compared with the untreated group under normal conditions; +++p<0.005 compared with the vehicle treated group under GD conditions; **p<0.01 2ME2 compared with the Compound E+2ME2 treated group; *p<0.05 Compound E compared with the Compound E+2ME2 treated groups. (C) Neuronal cell death was quantified in cultures that had been subjected to OGD. n=6, ***p<0.005 compared with the untreated group under normal condition; +++p<0.005 compared with the vehicle treated group under OGD condition. (D-G) Treatment with either Compound E or 2ME2 reduced the level of cleaved caspase-3, and combined treatment further reduced cleaved caspase-3 levels under GD (D, E) and OGD (F, G) conditions. (H) NICD and HIF-1α expression in 2ME2 and CE treated cultures. n=4 cultures in each group, * p<0.05 compared with vehicle-treated group; **p<0.01 compared with vehicle-treated group.

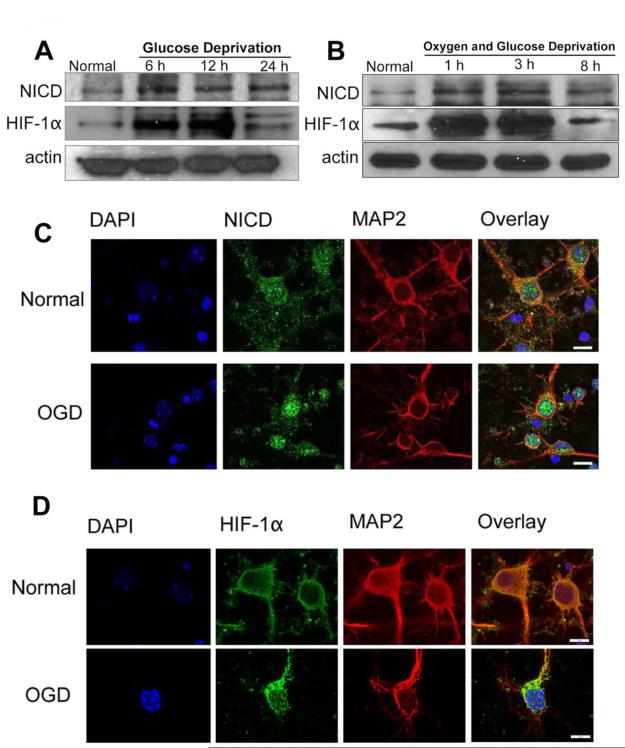

HIF-1α and Notch-1 co-localize in the nucleus of neurons in response to ischemia-like conditions

In order to investigate whether Notch-1 and HIF-1α cooperate in promoting neuronal death in stroke, we first analyzed the expression profiles of NICD and HIF-1α in primary cortical neurons under ischemia-like conditions. Levels of both NICD and HIF-1α increased after 6-24 h of GD and 1-8 h of OGD (Fig. 2A, B). NICD is believed to migrate into the nucleus and associate with a transcription factor, RBP-Jk, which up-regulates the expression of various Notch effector target genes (Guruharsha et al., 2012). Confocal imaging confirmed NICD accumulation in the nucleus following OGD (Fig. 2C). In normoxic conditions, hydroxylation of two proline residues and acetylation of a lysine residue at the oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD) of HIF-1α trigger its association with the pVHL E3 ligase complex, leading to HIF-1α degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Ke and Costa, 2006). Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α becomes stable and translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β forming a HIF-1 complex that becomes transcriptionally active and regulates the expression of target genes (Ke and Costa, 2006). Our confocal imaging analysis of cortical neurons immunostained with HIF-1α antibody confirmed increased levels of HIF-1α in the nucleus in response to OGD (Fig. 2D). Using confocal imaging, we next established that NICD and HIF-1α both accumulate in and around the nucleus during ischemia-like conditions (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. NICD and HIF-1α levels in primary cortical neurons under normal, GD and OGD conditions.

(A-B) Immunoblots showing NICD and HIF-1α protein levels at different time points during GD (A) and OGD (B) conditions. NICD levels were increased with GD and OGD treatment. HIF-1α levels increased from 6 h to 12 h of GD and from 1 h to 3 h of OGD, and then decreased at later time points. (C, D) Immunofluorescence images showing staining of NICD (C, green), HIF-1α (D, green), the neuronal marker MAP2 (red) and the nuclear marker 4′,6-diamidino- 2- phenylindol (DAPI) (blue). Both NICD and HIF-1α staining showed a slight increase at 8 h of OGD. Scale bar: 10 μm.

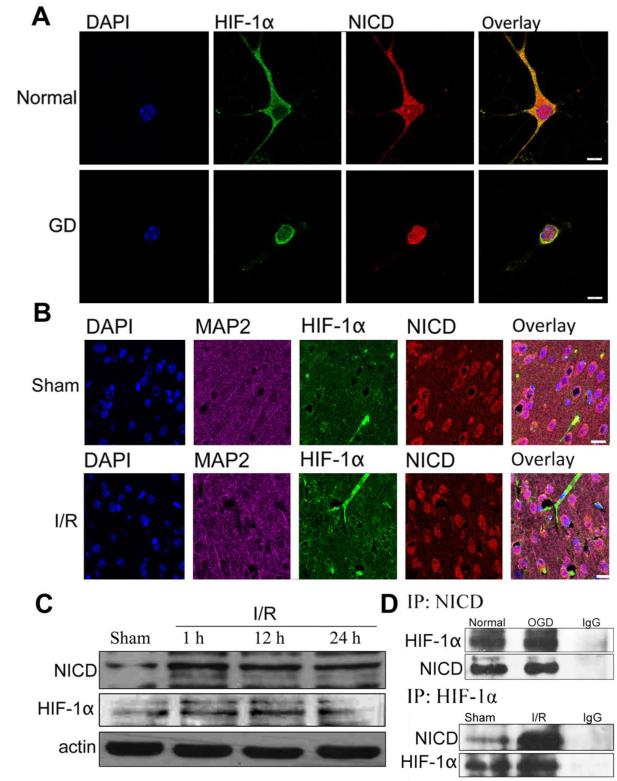

Figure 3. NICD and HIF-1α interaction in cortical neurons and mouse brain under ischemic conditions.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining of NICD and HIF-1α in mouse cortical neurons and neurons under GD conditions. NICD (red), HIF-1α (green) and DAPI (blue) staining showing translocation of NICD and HIF-1α from cytoplasm to the nucleus at 24 h GD. Scale bar: 20 μm. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of NICD and HIF-1α in the ipsilateral peri-infarct tissue section showing NICD (red), HIF-1α (green), MAP2 (magenta) and DAPI (blue) staining. The immunoreactivity of NICD and HIF-1α was more robust at 24 h after ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) compared to the sham control. Scale bar: 40 μm. (C) The expression level of NICD and HIF-1α were increased in the ipsilateral hemisphere after 1 h, 12 h and 24 h of I/R compared to sham. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of NICD and HIF-1α in neurons under OGD 8h and in brain tissue from the ipsilateral cerebral cortex following 1h ischemia and 24 h reperfusion showing increased binding of NICD and HIF-1α compared to controls.

We next examined whether Notch and HIF-1α are expressed after stroke in vivo. In the cerebral cortex of sham-operated control mice, little immunoreactivity with HIF-1α antibodies was observed and NICD appeared restricted to the neuronal cytoplasm (Fig. 3B). At 24 h after I/R, neurons in the ischemic cortex exhibited robust NICD immunoreactivity in both nucleus and cytoplasm, while the expression of HIF-1α around the nucleus was increased (Fig. 3B). Immunoblots of tissue samples taken from the ischemic cortex further demonstrated increased levels of NICD and HIF-1α proteins within 1–24 h of ischemia (Fig. 3C). Immunoprecipitation analysis of cortical neurons following OGD and of brain samples from the ischemic hemisphere showed that NICD and HIF-1α do indeed interact in cortical neurons. Co-immunoprecipitation data further supported the notion that Notch and HIF-1α bind directly to each other and/or are part of a multi-protein complex (Fig. 3D).

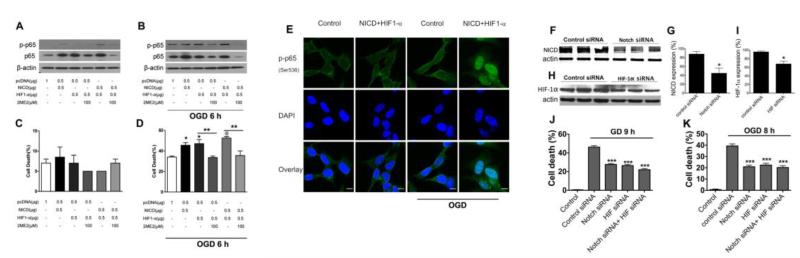

Over-expression of NICD and HIF-1α exacerbate neuronal death during ischemia-like conditions

In order to confirm that Notch and HIF-1α collaboration promotes cell death under ischemic conditions, SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were transfected with either NICD or HIF-1α. Our present data show that transfection with either NICD, HIF-1α, or both, increased expression of both the phosphorylated (p-p65) and non-phosphorylated (p65) forms of the 65 kDa subunit of NFκB under normal (Fig. 4A) and OGD conditions (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, 2ME2 treatment of cells transfected with NICD or HIF-1α alone, or both resulted in decreased levels of total and phosphorylated p65 under both normal and OGD conditions (Fig. 4A, B). Overexpression of HIF-1α and NICD had no significant effects on cell death under normoxic conditions (Fig. 4C). Cell death was substantially potentiated in NICD- or HIF-1α-transfected cells compared with the control pcDNA group under OGD conditions (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, cell death was increased in cells overexpressing NICD and HIF-1α compared with cells overexpressing either NICD or HIF-1α alone (Fig. 4D). In addition, treatment with 2ME2 reduced cell death induced by either HIF-1α or both NICD plus HIF-1α (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that NICD and HIF-1α can potentiate cell death under ischemic conditions and that ischemic cell death is exacerbated by combined elevation of NICD and HIF-1α levels. Immunocytochemical analyses of NICD and HIF-1α -transfected cells indicate nuclear translocation of p-p65 under OGD conditions (Fig. 4E). To evaluate the roles of endogenous Notch and HIF-1α in neuronal cell death under ischemic conditions, we used RNA interference to specifically knockdown endogenous Notch and HIF-1α (Fig. 4, F, G, H, I). Cell death was reduced in both GD- and OGD-induced cultures transfected with Notch siRNA and HIF-1α siRNA compared with the control siRNA group (Fig. 4, J, K). However, combined Notch and HIF-1α siRNA treatment did not achieve any further reduction in cell death. These results suggest that Notch and HIF-1α act via the same pathway during hypoxia/ischemia-induced cell death (Fig. 4F, G, H, I).

Figure 4. Effect of over-expression and inhibition of NICD and HIF-1α in neurons under ischemia-like conditions.

NICD and HIF-1α were transfected to SH-SY5Y cells to induce NICD and HIF-1α expression; Notch-1, HIF-1α siRNA were transfected to primary cortical neurons to inhibit endogenous NICD and HIF-1α expression. (A) Cells overexpressing NICD or HIF-1α showed an increased level of NF-κB p65/p-p65 when compared to cells transfected with control plasmid cDNA (pcDNA). The level of NF-κB p65/p-p65 was further increased when both NICD, HIF-1α were overexpressed. The NF-κB p65/p-p65 levels were reduced by treatment with 2ME2 under normal conditions (A) and 6 h of OGD (B). (C) Cell death in SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing NICD and HIF-1α. (D) Cell death in SH-SY5Y neurons was increased when NICD and HIF-1α were over-expressed, and was significantly reduced at 6 h OGD when treated with 2ME2. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of phosphorylated p65 in SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing NICD and HIF1-α under OGD (9 h) condition. Scale bar: 10 μm. (F, G) Knockdown of endogenous Notch-1 using Notch-1 siRNA. (H, I) Knockdown of endogenous HIF-1α using HIF-1α siRNA. (J) Cell death in neurons transfected with Notch-1 and HIF-1α siRNA was significantly reduced at 9 h GD (K) and 8 h OGD (J). n=3 cultures. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.005 compared with the vehicle treated group.

Inhibition of HIF-1α and γ-secretase protects against ischemic stroke-induced brain injury

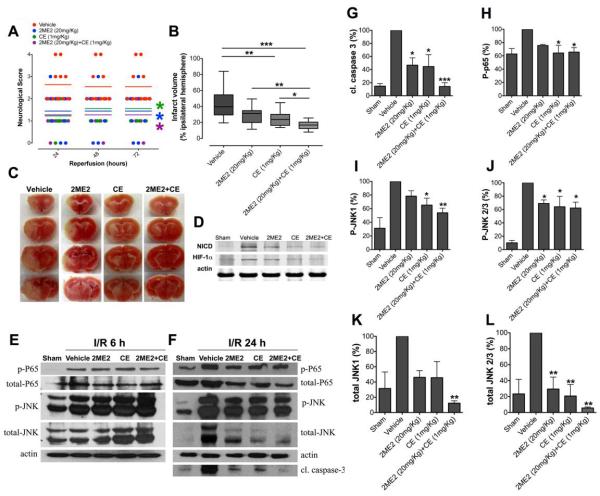

To determine whether blockade of both γ-secretase-mediated Notch activation and HIF-1α protect against stroke-induced brain injury by reducing the interaction between NICD and HIF1-α, we used the γ-secretase inhibitor CE and the HIF1-α inhibitor 2ME2. Treatment with either CE or 2ME2 by intravenous infusion immediately after ischemia resulted in reduced brain damage (Figs. 5A, B, C). In addition, combined CE and 2ME2 treatment further reduced brain damage (Fig. 5B, C). Next, we analyzed protein levels of NICD and HIF-1α in the ischemic hemisphere after 24 h of reperfusion (Fig. 5D). We found that both NICD and HIF-1α were elevated in the brain after ischemic stroke and reduced by treatment with CE and 2ME2 respectively (Fig. 5D). Next, we measured the levels of NF-κB phospho-p65 and JNK levels to assess whether inhibition of Notch and HIF-1α might protect against ischemic stroke-induced brain injury by affecting these proteins. Our data showed no significant difference in total and phospho-p65 and total and phospho-JNK levels between treatments groups (CE, 2ME2, or combination treatment) and the vehicle-treatment group after 6 h of reperfusion (n=5 in each group) (Fig. 5E). However, the levels of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 5F, G), NF-κB phospho-p65 (Fig. 5F, H), phospho-JNK1, 2/3 (Fig. 5F, I, J) and total JNK1, 2/3 (Fig. 5F, K, L) were all significantly reduced in the CE, 2ME2 and combined treatment groups compared with the vehicle-treatment group at 24 h reperfusion. Furthermore, combined CE and 2ME2 treatment further reduced cleaved caspase-3 and JNK levels (total JNK1 and phospho-JNK1) compared to either CE or 2ME2 treatments alone.

Figure 5. Inhibition of NICD and HIF-1α reduces focal ischemic brain injury in vivo.

(A and B) Mice underwent 1 h MCAO and 24-72 h reperfusion. Mice treated with CE (n=11) and 2ME2 (n=10), alone or in combination (n=13), exhibited improved neurological function and reduced brain injury after stroke, compared to vehicle-treated (n=11) mice. Neurological score was measured at 24, 48, and 72 h following reperfusion; infarct volume was measured at 72 h following reperfusion. Mice treated with both 2ME2 and CE treated showed significant reduction in infarct size compared to mice treated with either CE or 2ME2 alone. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. (C) Representative images of brains from each treatment group following 1 h MCAO and 72 h reperfusion. (D) NICD and HIF-1α expression in 2ME2 and CE treated mouse brains after MCAO and 24 h of reperfusion. n=5 in each group. (E) NF-κB p65/p-p65, total JNK/p-JNK expression in the ipsilateral brain hemisphere at 6 h I/R from mice treated with either 2ME2, CE, or both 2ME2 and CE. (F) Cleaved caspase-3, NF-κB p65/p-p65, total JNK/p-JNK expression in the ipsilateral brain hemisphere at 24 h I/R from mice treated with 2ME2, CE, and both 2ME2 and CE. (G, H, I, J, K, L) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3, p-p65 and total JNK/p-JNK expression. n=5 in each group, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.005 compared with the vehicle treated group.

Discussion

A major finding of this study is the compromising effect that Notch and HIF-1α signaling exert on neuronal viability after ischemic stroke, and that this neuronal damage can be inhibited under in vitro and in vivo conditions by treatment with inhibitors of γ-secretase and HIF-1α. Furthermore, blockade of both Notch and HIF-1α using a combination of γ-secretase and HIF-1α inhibitors resulted in enhanced neuroprotection. Notch and HIF-1αhave been shown to be important under both physiological and pathological conditions. HIF-1α interacts with NICD in order to maintain neural stem cells in an undifferentiated state under low oxygen conditions (Gustafsson et al., 2005). Hypoxia directly enhances Notch signaling by increasing and stabilizing NICD and recruiting HIF-1α to NICD and the Notch-responsive promoter, and consequently upregulates expression of downstream genes such as Hes1 and Herp1 (Gustafsson et al., 2005). In addition, NICD modulates HIF-1α post-transcriptionally by increasing the recruitment of HIF-1α to hypoxia response elements and the transcription of its target genes (Zheng et al., 2008). We previously showed that the γ-secretase inhibitors DAPT and CE reduce brain damage and neurological deficits when assessed 3 days after cerebral ischemia/ reperfusion; neither 2ME2 or CE affected cerebral blood flow immediately before or after MCAO (90-95% reduction in blood flow in the infarct region) (Arumugam et al., 2006). It was previously shown that the HIF-1α inhibitor 2ME2 worsens outcome after global ischemia in rats (Zhou et al., 2008) but is neuroprotective in focal ischemia by preserving blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity, and reducing brain edema and neuronal apoptosis (Chen et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2008). A recent study suggested a key role for Notch as a mediator in the crosstalk between HIF-1α and aspartyl-(asparaginyl)-β-hydroxylase (AAH) for the regulation of neuronal migration in primitive neuroectodermal tumor cells (Lawton et al., 2010). Further, the interaction of HIF-1α and Notch was found to be important in the regulation of medulloblastoma precursor cell proliferation and survival (Pistollato et al., 2010). Our data further supports the existence of a Notch-HIF-1α collaboration as NICD inhibition affects HIF-1α levels and, likewise, HIF-1α inhibition affects NICD levels under in vitro and in vivo ischemic conditions. However, further research is needed to unravel the precise molecular mechanisms of how Notch inhibition affects HIF-1α levels, and how HIF-1α inhibition affects NICD levels under cerebral ischemic conditions. These lines of evidence are consistent with the possibility that HIF-1α and Notch interact and additively contribute to neuronal injury under conditions of severe metabolic stress such as that which occurs in ischemic stroke.

Elevated NF-κB activation has also been demonstrated in various animal models of stroke, suggesting that this could contribute to the inflammatory reaction and apoptotic cell death in post-stroke brain injury. γ-secretase-mediated Notch signaling is required to sustain NF-κB activity, and NICD may increase NF-κB activity by binding to and enhancing the nuclear distribution of the active NF-κB signaling complex (Shin et al., 2006). The phosphorylation at serine 536 of p65 by IκB kinases has been shown to increase transcriptional activity (Sakurai et al., 1999). It has also been shown that phosphorylation of p65 at serine 536 contributes to various proinflammatory responses and neuronal vulnerability in ischemic stroke (Yang et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2003; Crack et al., 2006; Ryu et al., 2011). We found that treatment with a γ-secretase inhibitor reduces ischemia-induced levels of NF- κB-p65 in neurons, and that overexpression of NICD and HIF-1α increase expression of total and serine 536-phosphorylated NF-κB-p65 under normal and ischemic conditions. Furthermore, 2ME2 treatment resulted in decreased levels of total and serine 536-phosphorylated NF-κB-p65 under both normal and ischemic conditions, suggesting that NF-κB expression and activation is Notch-mediated and may also require HIF-1α. Moreover, cell death was further increased with combined NICD and HIF-1α overexpression compared with overexpression of either protein alone. In addition, 2ME2 treatment reduced cell death induced by either HIF-1α alone or both NICD and HIF-1α. These results provide further support for collaborative detrimental roles for NICD and HIF-1α signaling under ischemic conditions. Confocal imaging data revealed that serine 536-phosphorylated NF-κB-p65 translocates into the nucleus of NICD and HIF-1α -expressing cells under ischemia-like conditions, but not under normal conditions. This result can help explain the accelerated cell death during OGD conditions, while p65 and p-p65 were upregulated in both normoxia and OGD conditions. Therefore, this observation indicates that Notch and HIF-1α -mediated activation of NF-kB is a cellular signaling pathway that was specific to OGD conditions. Immunoprecipitation analysis of cortical neurons following OGD, and of brain samples from the ischemic hemisphere, revealed that an interaction between NICD and HIF-1α occurs under these conditions providing further evidence that NICD and HIF-1α interact following ischemia. Our data suggesting that NICD and HIF-1α interact in neuronal cells is consistent with a previous report that NICD and HIF-1α interact in muscle cells (Gustafsson et al., 2005).

It was recently shown that selective inhibition of early but not late expressed HIF-1α is neuroprotective in rats after focal ischemia (Yeh et al., 2011). Treating neurons with 2ME2 0.5 h after ischemic stress or pre-silencing HIF-1α with siRNA decreased brain injury, edema and apoptotic cell death (Yeh et al., 2011). Conversely, applying 2ME2 to neurons 8 h after ischemic stress, or silencing HIF-1α with siRNA 12 h after OGD, increased neuronal damage (Yeh et al., 2011). Another study showed that 2ME2 and D609 powerfully protect the brain from ischemic injury by inhibiting HIF-1α expression, attenuating expression of vascular endothelial growth factor to avoid blood-brain barrier disruption, and suppressing ceramide generation and neuronal apoptosis via the BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) pathway (Yu et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2007). The latter results demonstrate that HIF-1α induced early after ischemia leads to cellular apoptosis, whereas later induction of HIF-1α promotes survival. Coapplication of Notch siRNA and HIF-1α siRNA following ischemic conditions in vitro did not have an additive effect when compared to individual siRNA treatment, consistent with these two proteins acting via the same pathway during hypoxia/ischemia-induced cell death.

However, our current investigation following in vivo ischemia and reperfusion found that early inhibition of HIF-1α protects neurons in vitro and reduces neurological deficits and brain infarct volume in vivo; additional protection is obtained with combined inhibition of γ-secretase and HIF-1α.

In order to investigate the mechanism of enhanced protection by combined γ-secretase and HIF-1α inhibition, we analyzed the levels of NF-κB phospho-p65, JNK and cleaved caspase-3. Our data show that the levels of NF-κB phospho-p65, JNK and cleaved caspase-3 were all reduced by γ-secretase and HIF-1α inhibition alone or in combination when compared with vehicle control. Interestingly, JNK and caspase-3 levels were further reduced by combined γ-secretase and HIF-1α inhibition. This indicates that combined early intervention may lead to protection following stroke by targeting cell death pathways mediated by JNK activation. NICD has been shown to physically associate with the JNK binding domain of JNK-interacting protein 1 (JIP), thereby interfering with the binding of JIP1 and JNK and inhibiting JNK activation during GD (Kim et al., 2005). Another study showed that loss of Notch in Drosophila embryos resulted in high levels of JNK activity, indicating that Notch represses JNK signaling in development (Zecchini et al., 1999). However, our data show that treatment with a γ-secretase inhibitor leads to a reduction in ischemic stroke-induced phosphorylation of JNK. Furthermore, it was shown that treatment with D-JNKI1, a JNK-inhibiting peptide, rescues adult hypoxic neurons from death and contributes to HIF-1α upregulation, probably via a direct interaction with the HIF-1α protein (Antoniou et al., 2009). AP-1 is a transcription factor belonging to the leucine zipper family, and it has been demonstrated that ischemic or hypoxic conditions lead to an increase in JNK-AP-1 activity (Michiels et al., 2001; Tang et al., 2007). HIF-1α and AP-1 have been shown to cooperate to increase transcription (Michiels et al., 2001). Our findings suggest that ischemic stroke-induced elevation of total JNK levels was reduced by combined inhibition of Notch and HIF-1α. This may suggest roles for Notch and HIF-1α signaling in JNK expression following stroke. However, the exact molecular mechanisms by which the NICD-HIF-1α association affects JNK expression and augments neuronal damage in cerebral ischemia remain unknown and further research is needed to answer this question. In conclusion, our present findings suggest that agents that target the γ-secretase-Notch pathway and HIF-1α pathway may prove effective in reducing neuronal cell death and brain injury after ischemic stroke.

Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) can modulate Notch signaling

Notch- HIF-1α signaling contributes to ischemic neuronal death

Agents that target Notch- HIF-1α may prove effective stroke therapy

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grants (2012R1A2A2A01047551 & 2012R1A1A2009093), a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D project (A092042) from the Korean Government, a grant by National Heart Foundation of Australia for a Grant-In-Aid (G 09B 4272), an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council grant (NHMRC APP1008048), an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship to TVA (ARCFT100100427) and an Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

D.G.J, C.G.S., E.O., M.P.M. S.M., and T.V.A. designed the project. Y.L.C., J.S.P., S.H.B., Y.C., and T.V.A. performed the research. B.S.L., C.G.S. and T.M. contributed financial support, new reagents and analytic tools. Y.L.C., S.M., T.V.A. and D.G.J. analyzed the data. T.V.A., S.M., B.S.L., C.G.S., M.G., D.Y.W.F., T.M., M.P.M and D.G.J. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Antoniou X, Sclip A, Ploia C, Colombo A, Moroy G, Borsello T. JNK contributes to Hif-1alpha regulation in hypoxic neurons. Molecules. 2009;5:114–127. doi: 10.3390/molecules15010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Chan SL, Jo DG, Yilmaz G, Tang SC, Cheng A, Gleichmann M, Okun E, Dixit VD, Chigurupati S, Mughal MR, Ouyang X, Miele L, Magnus T, Poosala S, Granger DN, Mattson MP. Gamma secretase-mediated Notch signaling worsens brain damage and functional outcome in ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12:621–623. doi: 10.1038/nm1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Cheng YL, Choi Y, Choi YH, Yang S, Yun YK, Park JS, Yang DK, Thundyil J, Gelderblom M, Karamyan VT, Tang SC, Chan SL, Magnus T, Sobey CG, Jo DG. Evidence that gamma-secretase-mediated Notch signaling induces neuronal cell death via the nuclear factor-kappaB-Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death pathway in ischemic stroke. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:23–31. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Salter JW, Chidlow JH, Ballantyne CM, Kevil CG, Granger DN. Contributions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to brain injury and microvascular dysfunction induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2555–2560. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00588.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranova O, Miranda LF, Pichiule P, Dragatsis I, Johnson RS, Chavez JC. Neuron-specific inactivation of the hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha increases brain injury in a mouse model of transient focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6320–6332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0449-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron M, Yu AY, Solway KE, Semenza GL, Sharp FR. Induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and its target genes following focal ischaemia in rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4159–4170. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaudin M, Nedelec AS, Divoux D, MacKenzie ET, Petit E, Schumann-Bard P. Normobaric hypoxia induces tolerance to focal permanent cerebral ischemia in association with an increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and its target genes, erythropoietin and VEGF, in the adult mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:393–403. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton BR, Reutens DC, Sobey CG. Apoptotic mechanisms after cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2009;40:e331–339. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Hu Q, Yan J, Lei J, Qin L, Shi X, Luan L, Yang L, Wang K, Han J, Nanda A, Zhou C. Multiple effects of 2ME2 and D609 on the cortical expression of HIF-1alpha and apoptotic genes in a middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced focal ischemia rat model. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1831–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jadhav V, Tang J, Zhang JH. HIF-1 alpha inhibition ameliorates neonatal brain damage after hypoxic-ischemic injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;102:395–399. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-85578-2_77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Hu Q, Yan J, Yang X, Shi X, Lei J, Chen L, Huang H, Han J, Zhang JH, Zhou C. Early inhibition of HIF-1alpha with small interfering RNA reduces ischemic-reperfused brain injury in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;33:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack PJ, Taylor JM, Ali U, Mansell A, Hertzog PJ. Potential contribution of NF-kappaB in neuronal cell death in the glutathione peroxidase-1 knockout mouse in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006;37:1533–1538. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221708.17159.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demougeot C, Van Hoecke M, Bertrand N, Prigent-Tessier A, Mossiat C, Beley A, Marie C. Cytoprotective efficacy and mechanisms of the liposoluble iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl in the rat photothrombotic ischemic stroke model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:1080–1087. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.072744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias TB, Yang YJ, Ogai K, Becker T, Becker CG. Notch signaling controls generation of motor neurons in the lesioned spinal cord of adult zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3245–3252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6398-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guruharsha KG, Kankel MW, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The Notch signalling system: recent insights into the complexity of a conserved pathway. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:654–66. doi: 10.1038/nrg3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton R, Cui J, Scheel JR, Ellison JA, Ames C, Gibson C, Blouw B, Ouyang L, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S, Johnson RS, Lipton SA, Barlow C. Brain-specific knockout of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha reduces rather than increases hypoxicischemic damage. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4099–4107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4555-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou ST, MacManus JP. Molecular mechanisms of cerebral ischemia-induced neuronal death. Int Rev Cytol. 2002;221:93–148. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)21011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1469–1480. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Kim MJ, Kim KJ, Yun HJ, Chae JS, Hwang SG, Chang TS, Park HS, Lee KW, Han PL, Cho SG, Kim TW, Choi EJ. Notch interferes with the scaffold function of JNK-interacting protein 1 to inhibit the JNK signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14308–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501600102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M, Tong M, Gundogan F, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Aspartyl-(asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase, hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha and Notch cross-talk in regulating neuronal motility. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010;3:347–356. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.5.13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Narasimhan P, Yu F, Chan PH. Neuroprotection by hypoxic preconditioning involves oxidative stress-mediated expression of hypoxia-inducible factor and erythropoietin. Stroke. 2005;36:1264–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166180.91042.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels C, Minet E, Michel G, Mottet D, Piret JP, Raes M. HIF-1 and AP-1 cooperate to increase gene expression in hypoxia: role of MAP kinases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:49–53. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee D, Patil CG. Epidemiology and the global burden of stroke. World Neurosurg. 2011;76:S85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee T, Kim WS, Mandal L, Banerjee U. Interaction between Notch and Hif-alpha in development and survival of Drosophila blood cells. Science. 2011;332:1210–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1199643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JS, Manzanero S, Chang JW, Choi Y, Baik SH, Cheng YL, Li YI, Gwon AR, Woo HN, Jang J, Choi IY, Lee JY, Jung YK, Tang SC, Sobey CG, Arumugam TV, Jo DG. Calsenilin Contributes to Neuronal Cell Death in Ischemic Stroke. Brain Pathol. 2013;23:402–412. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Persano L, Abbadi S, Frasson C, Denaro L, D’Avella D, Panchision DM, Della Puppa A, Scienza R, Basso G. Interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and Notch signaling regulates medulloblastoma precursor proliferation and fate. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1918–1929. doi: 10.1002/stem.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang L, Wu T, Zhang HW, Lu N, Hu R, Wang YJ, Zhao L, Chen FH, Wang XT, You QD, Guo QL. HIF-1α is critical for hypoxia-mediated maintenance of glioblastoma stem cells by activating Notch signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:284–294. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu HJ, Kim JE, Yeo SI, Kim MJ, Jo SM, Kang TC. ReLA/P65-serine 536 nuclear factor-kappa B phosphorylation is related to vulnerability to status epilepticus in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2011;187:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. IkappaB kinases phosphorylate NF-kappaB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30353–30356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen WH, Zhang CY, Zhang GY. Antioxidants attenuate reperfusion injury after global brain ischemia through inhibiting nuclear factor-kappa B activity in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24:1125–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 as a therapeutic target in ischemic stroke. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:4593–4600. doi: 10.2174/092986709789760779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HM, Minter LM, Cho OH, Gottipati S, Fauq AH, Golde TE, Sonenshein GE, Osborne BA. Notch1 augments NF-kappaB activity by facilitating its nuclear retention. EMBO J. 2006;25:129–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NR, Muyderman H. Mitochondria, oxidative metabolism and cell death in stroke. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Sharma G, Mishra V. Hypoxia inducible factor-1: its potential role in cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:491–507. doi: 10.1007/s10571-012-9803-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D, Yin T, Smalstig EB, Hsu MA, Panetta J, Little S, Clemens J. Transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B is activated in neurons after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:592–603. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroka DM, Burkhardt T, Desbaillets I, Wenger RH, Neil DA, Bauer C, Gassmann M, Candinas D. HIF-1 is expressed in normoxic tissue and displays an organ-specific regulation under systemic hypoxia. FASEB J. 2001;15:2445–2453. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0125com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SC, Arumugam TV, Xu X, Cheng A, Mughal MR, Jo DG, Lathia JD, Siler DA, Chigurupati S, Ouyang X, Magnus T, Camandola S, Mattson MP. Pivotal role for neuronal Toll-like receptors in ischemic brain injury and functional deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13798–13803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702553104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z, Chigurupati S, Arumugam TV, Jo DG, Li H, Chan SL. Notch activation enhances the microglia-mediated inflammatory response associated with focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42:2589–2594. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.614834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin XY, Pan J, Wang XQ, Ma JF, Ding JQ, Yang GY, Chen SD. 2-methoxyestradiol attenuates autophagy activation after global ischemia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:631–638. doi: 10.1017/s031716710001218x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Tang E, Guan K, Wang CY. IKK beta plays an essential role in the phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2003;170:5630–5635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh SH, Ou LC, Gean PW, Hung JJ, Chang WC. Selective inhibition of early–but not late–expressed HIF-1α is neuroprotective in rats after focal ischemic brain damage. Brain Pathol. 2011;21:249–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZF, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Zhou D, Cheng G, Schuchman EH, Mattson MP. Pivotal role for acidic sphingomyelinase in cerebral ischemia-induced ceramide and cytokine production, and neuronal apoptosis. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;15:85–97. doi: 10.1385/JMN:15:2:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan TM, Yu HM. Notch signaling: key role in intrauterine infection/inflammation, embryonic development, and white matter damage? J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:461–468. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecchini V, Brennan K, Martinez-Arias A. An activity of Notch regulates JNK signalling and affects dorsal closure in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1999;9:460–469. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Linke S, Dias JM, Zheng X, Gradin K, Wallis TP, Hamilton BR, Gustafsson M, Ruas JL, Wilkins S, Bilton RL, Brismar K, Whitelaw ML, Pereira T, Gorman JJ, Ericson J, Peet DJ, Lendahl U, Poellinger L. Interaction with factor inhibiting HIF-1 defines an additional mode of cross-coupling between the Notch and hypoxia signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3368–3373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711591105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Matchett GA, Jadhav V, Dach N, Zhang JH. The effect of 2-methoxyestradiol, a HIF-1 alpha inhibitor, in global cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurol Res. 2008;30:268–271. doi: 10.1179/016164107X229920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Kohl R, Herr B, Frank R, Brune B. Calpain mediates a von Hippel-Lindau protein-independent destruction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1549–1558. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]