Abstract

Rationale

Drug effects on delay discounting are thought to reflect changes in sensitivity to reinforcer delay, although other behavioral mechanisms might be involved. One strategy for revealing the influence of different behavioral mechanisms is to alter features of the procedures in which they are studied.

Objective

This experiment examined whether the order of delay presentation under within-session delay discounting procedures impacts drug effects on discounting.

Methods

Rats responded under a discrete-trial choice procedure in which responses on one lever delivered 1 food pellet immediately and responses on the other lever delivered 3 food pellets either immediately or after a delay. The delay to the larger reinforcer (0, 4, 8, 16, and 32 s) was varied within session and the order of delay presentation (ascending or descending) varied between groups.

Results

Amphetamine (0.1–1.78 mg/kg) and methylphenidate (1.0–17.8 mg/kg) shifted delay functions upward in the ascending group (increasing choice of the larger reinforcer) and downward in the descending group (decreasing choice of the larger reinforcer). Morphine (1.0–10.0 mg/kg) and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (0.32–5.6 mg/kg) tended to shift the delay functions downward, regardless of order of delay presentation, thereby reducing choice of the larger reinforcer, even when both reinforcers were delivered immediately.

Conclusion

The effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate under delay discounting procedures differed depending on the order of delay presentation indicating that drug-induced changes in discounting were due, in part, to mechanisms other than altered sensitivity to reinforcer delay. Instead, amphetamine and methylphenidate altered responding in a manner consistent with increased behavioral perseveration.

Keywords: amphetamine, methylphenidate, morphine, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, delay discounting, order of delay presentation, perseveration, lever press, rats

Delay discounting is a process whereby the effectiveness of a consequence decreases as a hyperbolic function of the delay to its presentation (Mazur 1987; Rachlin et al. 1991; Richards et al. 1997). Delay discounting has been the focus of much research, in part, because of its apparent relevance to many socially important behavioral problems. For example, delay discounting is presumed to be one of the processes underlying the tendency to choose smaller, immediately available reinforcers over larger, delayed reinforcers (Ainslie 1974; Rachlin and Green 1972; Logue 1988; Evenden 1999). Studies with humans show a correlation between rates of delay discounting and the likelihood of exhibiting problematic behavioral patterns, including substance abuse, pathological gambling, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (e.g., Yi et al. 2010; Petry and Madden 2010; Williams 2010; see also Bickel et al. 2012).

Many procedures have been used to study delay discounting in humans and other species (see Madden and Bickel 2010) and among the more commonly used are procedures in which responding on one manipulandum (e.g. lever) delivers a small reinforcer (e.g., one food pellet) immediately and responding on another lever delivers a larger reinforcer (e.g., three food pellets) either immediately or following a delay (Evenden and Ryan 1996). Typically, during the first block of the session, both reinforcers are available immediately, and the delay to the larger reinforcer increases across successive blocks. Consequently, a delay function can be obtained within a single session by measuring the change in response allocation across successive blocks. After sufficient exposure to the contingencies, stable choice patterns emerge that reflect delay discounting; as the delay to the larger reinforcer increases, responding shifts from the alternative associated with the larger reinforcer to the alternative associated with the smaller, immediately available reinforcer. Within-session determination of delay functions facilitates efficient assessment of the effects of many variables (e.g., drug administration) on delay discounting. The most common procedure is one in which the delay progressively increases across blocks (i.e., ascending delays).

Changes in performance under ascending delay procedures are often interpreted as changes in discounting. For example, stimulant drugs such as amphetamine have been studied under delay discounting procedures because of the association between substance abuse and enhanced discounting and because stimulants are used to treat behavioral disorders thought to reflect increased impulsivity (e.g., ADHD). Stimulants tend to shift delay discounting functions rightward or upward reflecting increased choice of larger, delayed reinforcers (Cardinal et al. 2000; Floresco et al. 2008; Pitts and McKinney 2005; Slezak and Anderson 2011; van den Bergh et al. 2006; van Gaalen et al. 2006; Winstanley et al. 2003; Winstanley et al. 2005; but see Evenden and Ryan 1996; Koffarnus et al. 2011; see also de Wit and Mitchell 2010, for a review), possibly reflecting a reduction in sensitivity to reinforcer delay. Indeed, amphetamine attenuates sensitivity to reinforcer delay under other conditions (e.g., Ta et al. 2008); however, other factors might play a role including whether the delay period is paired with a unique stimulus (signaled delay; Cardinal et al. 2000).

Enhancement of responding for a larger, delayed reinforcer under procedures in which the delay increases during the session could reflect the influence of other mechanisms as well. Because subjects respond predominantly for the larger reinforcer during the first block when both reinforcers are delivered immediately, conditions that decrease behavioral flexibility (e.g., increase perseveration) might increase responding for the larger reinforcer in subsequent blocks, an effect that resembles attenuation of delay discounting. In one study (Slezak and Anderson 2009), rats were trained and tested under ascending and descending (the largest delay was arranged during the first component of the session) orders of delay presentation; amphetamine tended to decrease choice of the larger, delayed reinforcer (i.e., enhance discounting) under both orders of delay but did so to a lesser extent under the ascending order, suggesting that the order with which the delays are presented might impact the effects of amphetamine on discounting. St. Onge et al. (2010) compared the effects of drugs on choice between a smaller certain reinforcer and a larger uncertain reinforcer, in different groups of rats responding under either an ascending or descending order of probability (probability of reinforcement changed within session). The non-selective dopamine receptor antagonist flupenthixol shifted the probability discounting function upward under both the ascending and descending orders; however, amphetamine shifted the function upward in the ascending order but downward in the descending order indicating that the effects of amphetamine under a probability discounting procedure can depend on procedural variations. Amphetamine also reduced the likelihood of switching between two alternatives under operant choice procedures in a manner consistent with increased perseveration (e.g., Todorov et al. 1972). Collectively, these data suggest that changes in performance under ascending delay procedures might not be due exclusively to changes in sensitivity to delay. Indeed, other factors (e.g., preservation) might contribute to drug effects on discounting (e.g., Pitts and McKinney 2005; Slezak and Anderson 2009); however, any impact of order of delay presentation remains unclear.

The present study examined the effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate on delay discounting in separate groups of rats responding under an ascending or a descending order of delay presentation. If increased choice of the larger, delayed reinforcer under ascending delay procedures is due primarily to a reduction in sensitivity to delay, similar effects should be observed using procedures with different orders of delay presentation: sensitivity to delay should be impacted similarly with delay curves shifted upward. Conversely, if increased choice of larger, delayed reinforcers in procedures with ascending order of delay presentation is due to increased perseveration, then upward shifts should not be observed in subjects responding under a descending order of delay presentation. Rather, responding during the latter part of the session should correspond more closely to responding during the earlier part of the session in each group. Subjects that respond for the smaller reinforcer early in the session (e.g., when responding under a descending order of delay presentation), should continue to do so as the session progresses irrespective of changes in delay, resulting in a reduced amount of responding for the larger reinforcer. To test the generality of any interaction between stimulant drugs and order of delay presentation, drugs with different pharmacological mechanisms of action (morphine and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol [THC]) were also tested in rats responding under ascending or descending orders of delay presentation.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Twelve experimentally naïve, adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories Inc., Indianapolis, IN), approximately 3 months old at the beginning of the experiment, were housed individually in 45 × 24 × 20 cm plastic cages containing rodent bedding (Sani-chips, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) in a colony room maintained on a 12:12 light/dark cycle; experiments were conducted in the light period. Rats were fed chow (Rat Sterilizable Diet, Harlan Teklad) after daily experimental sessions to maintain their body weights between 340 and 350 g. Water was available continuously in the home cage. Animals were maintained and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and with the 2011 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources on Life Sciences, National Research Council, and the National Academy of Sciences).

Apparatus

Sessions were conducted in sound-attenuating, well ventilated enclosures (Model ENV-022M and ENV-008CT; MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT), which contained an operant conditioning chamber of which two sides were Plexiglas and one side was a stainless steel response panel equipped with two metal response levers 11.5 cm apart. A 2.5-cm diameter translucent circle that could be illuminated was located on the response panel above each lever and a 5 × 5 cm opening located equidistant between the two levers was available for food pellet delivery. Food pellets (45 mg; PJAI-0045; Noyes Precision Pellets, Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) were delivered from a food hopper external to the operant chamber, but within the enclosure. Data were collected using MED-PC IV software and a PC-compatible interface (Med-Associates, Inc.).

Behavioral Procedure

Rats were first trained to press either of two levers for food. At the beginning of daily 30-min sessions the houselight and each lever light were illuminated; a response on either lever turned off both lever lights and delivered one food pellet immediately followed by re-illumination of the lever lights and another opportunity to respond. After 3 consecutive sessions in which 50 food pellets were delivered within 30 min, the number of food pellets delivered for responding on the non-preferred lever (i.e., less than 50% of responses over the same 3 sessions) was increased from 1 to 3. Within 1 to 5 sessions all rats responded nearly exclusively on the lever that delivered 3 pellets, after which the experimental procedure was introduced that was based on studies by Evenden and Ryan (1996).

Sessions were conducted once daily, 6 or 7 days per week and began with a 10-min timeout during which the chamber was dark and responses had no programmed consequence. The houselight was illuminated at the beginning of each block and remained illuminated continuously for the duration of the block. Illumination of a light above one lever or both levers signaled the beginning of a trial. A response on an active lever (i.e., located directly below an illuminated lever light) delivered either 1 food pellet immediately or 3 food pellets either immediately or after a delay (0, 4, 8, 16, or 32 s). This series of delays was introduced for all subjects immediately upon implementation of the multiple-block sessions. When food was delivered immediately, the lever lights(s) was (were) extinguished immediately after a response. When food was delivered after a delay, the light located above the pressed lever blinked on and off at 0.5 s intervals during the delay. The lever that delivered 3 food pellets was counterbalanced across rats and was maintained for an individual rat for the entire study. If no response was made within 20 s of the beginning of a trial (limited hold), the light(s) was extinguished and the trial was recorded as an omission. Trials began every 60 s regardless of responding.

Experiment 1: Amphetamine and Methylphenidate

Sessions consisted of 5 blocks separated by 30-s timeout periods during which the chamber was dark (the houselight and both lever lights were extinguished) and lever presses had no programmed consequence. Each block comprised 2 forced (sampling) trials followed by 10 choice trials; forced trials ensured contact with the contingencies that were active during the ensuing choice trials of that block. During a forced trial, 1 lever light was illuminated and a response on the lever located below the light delivered a reinforcer (1 pellet immediately or 3 pellets either immediately or after a delay). During a second forced trial, the other lever light was illuminated and a response on the lever located below that light delivered a reinforcer (i.e., the reinforcer that was not delivered during the first forced trial). The order of presentation of forced trials (left/right or right/left) was determined randomly across blocks. The remaining 10 trials of each block were choice trials during which both lever lights were illuminated and a single response on either lever delivered the corresponding reinforcer according to the contingencies arranged for that block.

Two groups of rats (n = 6/group) were studied. In one group (ascending), both reinforcers were delivered immediately during the first block and the delay to delivery of the larger reinforcer increased progressively (0, 4, 8, 16, and 32 s) across subsequent blocks. In the other group (descending), the order of delay presentation was reversed such that the longest delay was arranged in the first block with delay (32, 16, 8, 4, 0 s) diminishing across subsequent blocks so that both reinforcers were delivered immediately during the final block.

Training continued for at least 20 sessions and until the following criteria were satisfied: 1) percentage of choices of the larger reinforcer in the no-delay block for each of 3 consecutive sessions was at least 80%; and 2) percentage of choice of the larger reinforcer in the block with the longest delay (32 s) for each of 3 consecutive sessions varied by no more than 20%. To determine if within-session shifts in responding were due to the delay rather than other features of the experiment (e.g., passage of time), delay was removed from all blocks of consecutive sessions (i.e., a response on either lever resulted in immediate delivery of a reinforcer) until the percentage of choices for the larger reinforcer was at least 80% in all blocks of a single session. Thereafter, delays were reinstated for at least 1 session and until responding was deemed stable (see above), at which point the effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate were determined.

Experiment 2: Morphine and THC

Experiment 2 was identical to Experiment 1 except that the number of choice trials was reduced to 5 per block (from 10) in order to reduce the session duration. After completing Experiment 1, one rat (A1) became ill and was removed from the study; the performance of another rat (in the descending group, D4) became unreliable and this rat was also removed from the study. Thus, the ascending and descending groups in Experiment 2 included 5 rats each. The effects of morphine and THC were determined during Experiment 2 followed by a re-determination of selected doses of amphetamine to test whether additional training and testing with drug altered sensitivity of rats to the effects of amphetamine.

Pharmacological Procedure

Amphetamine, morphine, and THC (100 mg/ml in absolute ethanol) were provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Research Technology Branch, Rockville, MD, USA), and methylphenidate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Amphetamine, morphine, and methylphenidate were dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride. THC was dissolved in a 1:1:18 mixture of absolute ethanol, Emulphor-620 (Rhone-Poulenc Inc., Princeton, New Jersey, USA), and 0.9% sodium chloride. All drugs were administrated i.p. in a volume of 1.0 ml/kg of body weight. Test sessions were separated by at least 3 saline sessions. Saline sessions continued until the stability criteria used in the baseline training were satisfied (see above).

Amphetamine was studied first in all rats at the following doses and order: 0.1, 0.32, 0.56, 1.0, and 1.78 mg/kg. The doses of methylphenidate studied were 1.0, 3.2, 10, and 17.8 mg/kg. In Experiment 2, morphine (1.0, 3.2, 5.6, and 10.0 mg/kg) was studied first followed by THC (0.32, 1.0, 3.2 and 5.6 mg/kg); doses of both drugs were studied in ascending order. Successive doses of THC were studied at least 6 days apart (rather than 3). After studies with THC, the effects of 1.0 and 1.78 mg/kg of amphetamine were determined a second time in all rats. Injections of amphetamine or methylphenidate were given 5 min prior to the rat being placed in the chamber whereas injections of morphine or THC were administered 40 min prior to the rat being placed in the chamber. Once the rat was in the chamber, there was a 10-min timeout prior to initiation of the first trial; thus, pretreatment times corresponded to either 15 (amphetamine and methylphenidate) or 45 (morphine and THC) min. Data from the session immediately preceding the first test with a drug were used as control data for that drug. Except for the redetermination of the effects of amphetamine at the end of Experiment 2, all doses were tested no more than once in each subject.

Data Analyses

For each session, the total number of trials completed, the time to complete each trial (trial completion latency), and the number of responses emitted on each lever during choice trials were recorded. Delay functions were obtained by plotting the percentage of responses for the larger reinforcer (responses for the larger reinforcer/total responses * 100) as a function of delay. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal method similar to that described by Myerson et al. 2001. At least half of the trials during a block (5 trials/block in Experiment 1; 3 trials/block in Experiment 2) had to be completed in order for data from that block to be included in the delay function and data from all five blocks were required to calculate AUC.

Baseline differences in responding between groups were analyzed using a two-tailed t-test; AUC values from the last three sessions of the Baseline 1 phase were averaged for an individual subject which were then used for the between-groups comparison. One-way ANOVAs were used to compare baseline levels of responding at the end of the Baseline 1 phase (i.e., last session) with the control data obtained prior to determining the effects of each drug. Control data were from the session immediately prior to administration of the first dose of a particular drug. Comparisons were conducted for Experiment 1 by comparing Baseline 1 data with control data for amphetamine and methylphenidate. For Experiment 2 comparisons were made between Baseline 1 data and control data for morphine, THC, and the second determination of amphetamine; only data from rats that participated in Experiment 2 were included in this analysis. The effects of each drug on AUC, trials completed, and response latency were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA with dose as a within-subject factor and order of delay presentation as a between-subjects factor. Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using Dunnett’s test. Analyses were conducted using NCSS 8 (Kaysville, UT) which allows for ANOVAs to be calculated when AUC values are missing for an individual subject (e.g., due to decreases in the number of trials completed).

Results

Baseline training

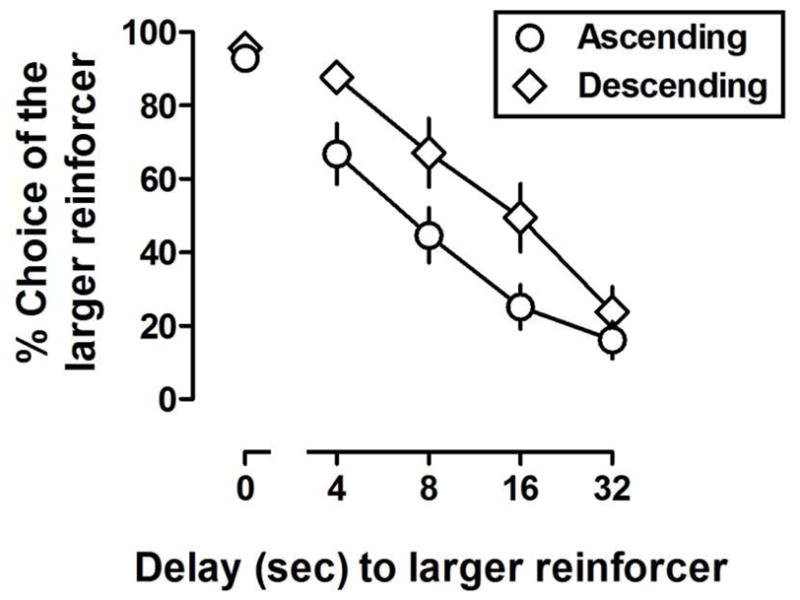

The mean number of sessions required to initially satisfy the stability criteria was 28.3 and 22.7 for the ascending and descending groups, respectively (Baseline 1, Table 1) with all but one rat (A6) reaching stability in fewer than 30 sessions. Figure 1 shows the group means (±SEM) for percent choice of the larger reinforcer as a function of delay (data are the average of the last three sessions of the first baseline phase). Rats in both groups responded predominantly (>90%) for the larger reinforcer when both reinforcers were delivered immediately (data above “0”). Mean (±SEM) percent choice of the larger reinforcer in the block with no delay was 92.7 (±2.7) and 95.5 (±2.9) for the ascending and descending groups, respectively. Percent choice of the larger reinforcer decreased as a function of delay to the larger reinforcer. In the ascending and descending groups, percent choice of the larger reinforcer in the block with a 32-s delay was 16.1 (±4.97) and 23.9 (±6.7), respectively (Figure 1). Baseline AUC values for the ascending (mean = 0.48±0.11) and descending (mean = 0.66±0.12) groups were not significantly different [t (10) = 2.15, p = 0.0571]. When the delays were removed, rats responded greater than 80% for the larger reinforcer in all blocks, typically within 1 to 3 sessions and always within 7 sessions (No Delay 1, Table 1). Following reinstatement of delays, rats in the ascending and descending groups required, on average, 2.2 and 3.8 sessions, respectively, to meet the stability criteria for drug testing (Baseline 2, Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of sessions required to satisfy conducted under each training condition.

| Rat | Baseline 1 | No Delay 1 | Baseline 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending | |||

| A1 | 21 | 1 | 1 |

| A2 | 24 | 1 | 2 |

| A3 | 22 | 2 | 2 |

| A4 | 26 | 1 | 1 |

| A5 | 22 | 4 | 5 |

| A6 | 55 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 28.3 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| Descending | |||

| D1 | 21 | 5 | 7 |

| D2 | 24 | 3 | 3 |

| D3 | 25 | 7 | 5 |

| D4 | 23 | 3 | 4 |

| D5 | 20 | 1 | 2 |

| D6 | 23 | 2 | 2 |

| Mean | 22.7 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

Figure 1.

Percent choice of the larger reinforcer as a function of delay (sec) to the larger reinforcer in separate groups of rats (n = 6/group) trained under an ascending (circles) or a descending (diamonds) order of delay presentation at the end of the first baseline training phase. Data points represented the group means and error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Experiment 1

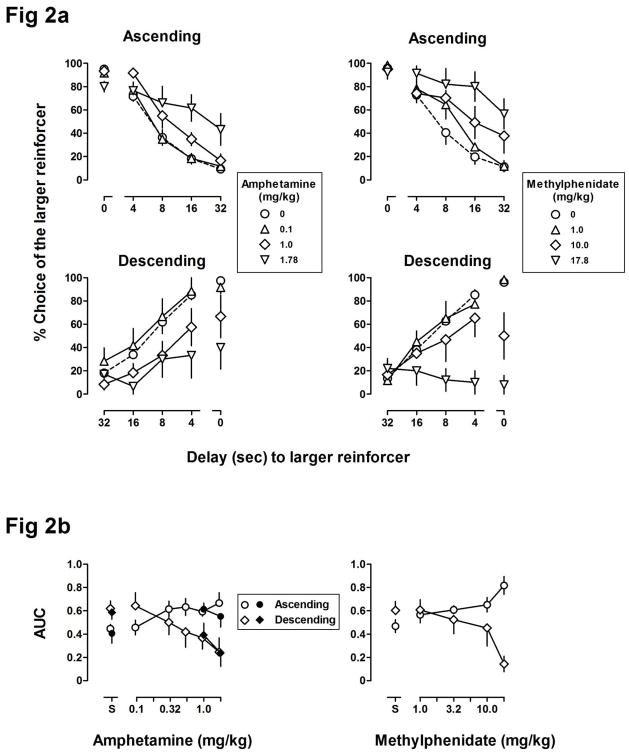

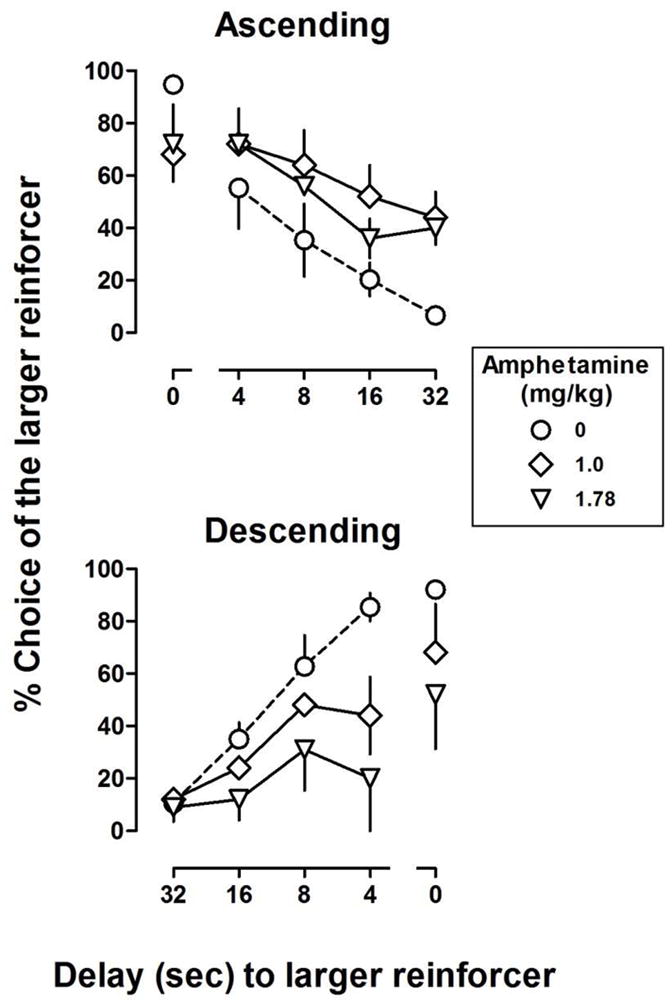

For both groups, control AUC values obtained prior to testing with amphetamine and with methylphenidate were not significantly different from baseline. In the ascending group (top, left panel, Figure 2a), amphetamine did not significantly alter choice in the block with no delay (i.e., the first block of the session; data above “0”) and increased choice of the larger reinforcer in blocks with delay, resulting an upward shift and a flattening of the delay function. In the descending group (bottom, left panel, Figure 2a), amphetamine did not significantly alter choice during the block with the 32-s delay (the first block of the session; data above “32”) and dose-dependently reduced choice of the larger reinforcer in blocks with shorter delays as well as when both reinforcers were delivered immediately, resulting in a flattening of the delay function. Amphetamine dose-dependently increased AUC in the ascending group (circles, left panel, Figure 2b) and decreased AUC in the descending group (diamonds, left panel, Figure 2b), resulting in a significant main effect of dose [F(5,50) = 2.46, p < .05] on AUC and a significant dose by delay order interaction [F(5,50) = 7.52, p < .001]. The largest dose of amphetamine tested (1.78 mg/kg) produced a small, but significant increase in response latency [F(5,50) = 3.28, p < .05] but did not significantly reduce the number of trials completed (Table 2); there was no main effect of order of delay presentation and no order by dose interaction for either trial completion latency or trials completed.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a shows the effects of amphetamine (left panels) and methylphenidate (right panels) on delay functions in the ascending (top panels) and descending (bottom panels) groups (n = 6/group). Figure 2b shows area under the delay curves (AUC, calculated from curves shown in Figure 2a) plotted as a function of the dose of amphetamine (left panel) or methylphenidate (right panel). Closed symbols in the left panel of Figure 2b show results from redetermination of the effects of selected doses of amphetamine in Experiment 2 (n=5/group). See Figure 1 for other details.

Table 2.

Mean (±SEM) trial completion latency and number of trials completed during Experiment 1.

| Drug, dose (mg/kg) | Ascending

|

Descending

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency (sec) | Trials Completed | Latency (sec) | Trials Completed | |

| Amphetamine | ||||

| Saline | 1.6 (0.1) | 50 (0) | 1.6 (0.3) | 50 (0) |

| 0.1 | 1.6 (0.1) | 49.7 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | 49.8 (0.2) |

| 0.32 | 1.5 (0.1) | 49.8 (0.2) | 1.2 (0) | 50 (0) |

| 0.56 | 1.5 (0.2) | 49.7 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.6) | 49.7 (0.3) |

| 1.0 | 1.7 (0.3) | 50 (0) | 1.6 (0.2) | 49.7 (0.3) |

| 1.78 | 2.3 (0.5) | 48.3 (1.5) | 2.7 (0.9) | 40.8 (7.4) |

| Methylphenidate | ||||

| Saline | 1.6 (0.1) | 50 (0) | 2.1 (0.4) | 50 (0) |

| 1.0 | 1.6 (0.1) | 49.8 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.3) | 49.8 (0.2) |

| 3.2 | 1.8 (0.2) | 49.7 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 50 (0) |

| 10.0 | 2.8 (0.5) | 46.8 (1) | 2 (0.4) | 47.7 (2.1) |

| 17.8 | 3.1 (0.8) | 44.8 (2.1) | 4.7 (1.1) | 42.6 (3.1) |

Like amphetamine, methylphenidate shifted the delay function upward in the ascending group (top, right panel, Figure 2a) and downward in the descending group (bottom, right panel, Figure 2a). Methylphenidate dose-dependently increased AUC in the ascending group (circles, right panel, Figure 2b) and decreased AUC in the descending group (diamonds, right panel, Figure 2b), resulting in a significant dose by delay order interaction [F(4,38) = 6.97, p < .001]. A dose of 17.8 mg/kg of methylphenidate produced a small but significant increase in response latency [F(4,38) = 8.81, p < .001] and reduced the number of trials completed [F(4,38) = 9.49, p < .001] (Table 2) with no main effect of order of delay presentation and no delay order by dose interaction for either trial completion latency or trials completed.

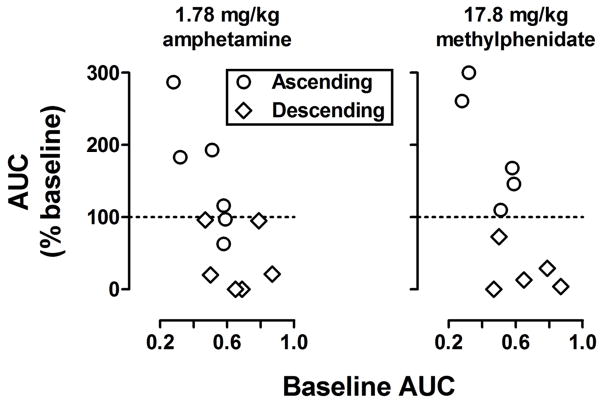

Figure 3 summarizes results obtained in individual rats with the largest doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate. After administration of 1.78 mg/kg of amphetamine, AUC increased for 4 of 6 rats in the ascending group and decreased for all 6 rats in the descending group (left panel, Figure 3). After administration of 17.8 mg/kg of methylphenidate, AUC increased for all 6 rats in the ascending group and decreased for all 6 rats in the descending group (right panel, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The percent change in AUC (abscissae) plotted as a function of baseline AUC (ordinates) for individual subjects in the ascending (circles) and descending (diamonds) groups after receiving 1.78 mg/kg amphetamine (left) or 17.8 mg/kg methylphenidate (right).

Experiment 2

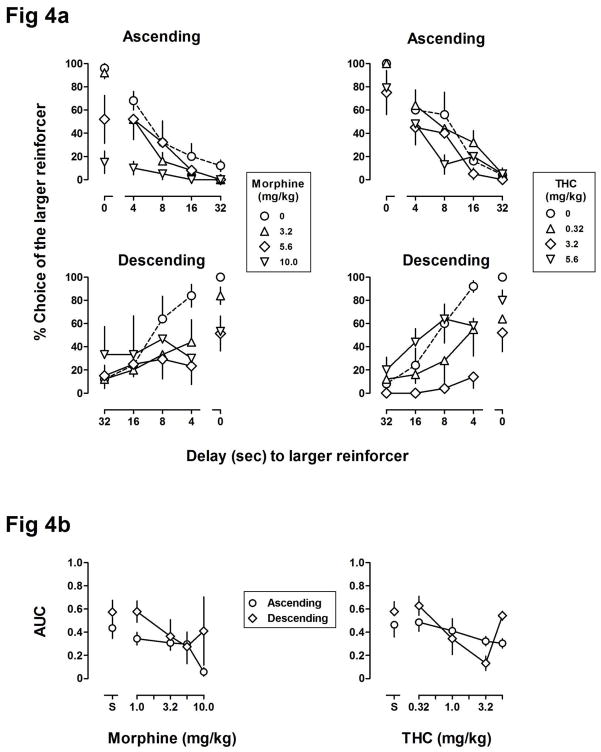

After the number of choice trials per block was reduced from 10 to 5, subjects responded under the new conditions for at least 5 sessions and until the stability criteria described above were again satisfied. Reducing the number of choice trials per block did not significantly alter the baseline delay functions in either group. For both groups, a comparison of baseline data (AUC from Baseline 1) with control data obtained prior to testing with morphine, THC, and the second determination of amphetamine revealed no significant differences. In both groups, morphine dose-dependently reduced choice of the larger reinforcer, particularly in blocks with no delay or with shorter delays, and had little effect on responding in blocks with longer delays (left panels, Figure 4a). Moreover, morphine reduced AUC similarly in both groups, resulting in a significant main effect of dose [F(4,29) = 5.31, p < .01] but no main effect of group and no delay order by dose interaction (left panel, Figure 4b). The largest dose of morphine tested (10.0 mg/kg) significantly increased trial completion latencies [F(4,32) = 10.72, p < .001] and reduced the number of trials completed [F(4,32) = 9.61, p < .001] (Table 3) with no main effect of order of delay presentation and no delay order by dose interaction for either trial completion latency or trials completed.

Figure 4.

Figure 3a shows effects of morphine (left panels) and THC (right panels) on delay functions in the ascending (top panels) and descending (bottom panels) groups (n = 5/group). Figure 3b shows AUC (calculated from curves shown in Figure 3a) plotted as a function of the dose of morphine (left panel) or THC (right panel). See Figures 1 and 2 for other details.

Table 3.

Mean (±SEM) trial completion latency and number of trials completed during Experiment 2.

| Drug, dose (mg/kg) | Ascending

|

Descending

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latency (sec) | Trials Completed | Latency (sec) | Trials Completed | |

| Morphine | ||||

| Saline | 2.1 (0.4) | 24.8 (0.2) | 3 (1.2) | 25 (0) |

| 1.0 | 2.2 (0.2) | 25 (0) | 3 (0.9) | 24.6 (0.4) |

| 3.2 | 2.2 (0.4) | 24.6 (0.4) | 2.4 (1.1) | 24.6 (0.4) |

| 5.6 | 1.6 (0.3) | 25 (0) | 4 (1.5) | 22.6 (1.5) |

| 10.0 | 8.2 (3.4) | 17.4 (4.9) | 13.8 (3.3) | 10.6 (4.7) |

| THC | ||||

| Saline | 1.9 (0.5) | 24.4 (0.6) | 2.8 (1.1) | 25 (0) |

| 0.32 | 1.7 (0.3) | 24.6 (0.2) | 1.9 (0.6) | 25 (0) |

| 1.0 | 1.4 (0.1) | 25 (0) | 2.5 (0.9) | 24.4 (0.4) |

| 3.2 | 7 (3.4) | 18.8 (4.8) | 4.9 (1.2) | 22.2 (1.8) |

| 5.6 | 5 (1.8) | 21.6 (2.1) | 2.3 (0.4) | 24.8 (0.2) |

THC modestly reduced choice of the larger reinforcer resulting in a downward shift in the delay function (right panels, Figure 4a). THC reduced responding for the larger reinforcer, particularly in blocks with no delay or shorter delays. Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of dose of THC [F(4,30) = 5.85, p < .01] on AUC and a significant dose by delay order interaction [F(4,30) = 2.92, p < .05] (right panel, Figure 4b). THC did not have a significant effect on the number of trials completed in either group; however there was a significant main effect of dose on trial completion latency [F(4,32) = 3.5, p < .05] but no main effect of delay order or delay order by dose interaction.

Figure 5 shows results from redetermination of the effects of 1.0 and 1.78 mg/kg of amphetamine in the ascending (top panel) and descending (bottom panel) groups following tests with THC and 6 to 9 months after the initial tests with amphetamine. Consistent with effects obtained earlier in the study, amphetamine flattened the delay curve in both groups and did so by increasing choice of the larger, delayed reinforcer in the ascending group and decreasing choice of the larger reinforcer in the descending group (compare open and closed symbols, left panel, Figure 2b). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant dose by delay order interaction for AUC [F(2,16) = 6.2, p < .05] with no effect on trials completed or trial completion latency.

Figure 5.

The effects of the second determination of amphetamine on the delay functions in the ascending (top panels) and descending (bottom panels) groups (n = 5/group). AUC calculated from data shown in Figure 4 are plotted in the left panel of Figure 2b for comparison to initial results obtained with amphetamine. See Figure 1 for other details.

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of the order of delay presentation to drug effects on performance under a delay-discounting procedure in rats (Evenden and Ryan 1996). Different groups of rats were trained under an ascending or a descending order of delay presentation. The effects of two stimulant drugs (amphetamine and methylphenidate) and two drugs that have other pharmacological effects (morphine and THC) were assessed. Responding maintained under either order of delay presentation was sensitive to reinforcer amount and delay. During the block in which both reinforcers were delivered immediately, rats responded predominantly (>90%) for the larger reinforcer, demonstrating sensitivity to reinforcer amount. When the delivery of the larger reinforcer was delayed, responding for the larger reinforcer decreased (and responding for the smaller reinforcer increased) as a function of delay. Both groups of rats showed comparable rates of discounting (Figure 1) and the number of training days required to establish adequate delay discounting performance did not differ markedly between the groups (Table 1). Moreover, within several session of the delay being removed from all blocks, rats responded predominantly for the larger reinforcer in all blocks, indicating that delay was a primary determinant of response choice. Others (Fox et al. 2008) showed that a descending order of delay produced a more steep delay discounting function as compared with an ascending order (see Robles et al. 2009 for evidence of a delay-order effect in humans). In the current study area under the delay curves generated under two different orders of delay were not statistically different, although there was a tendency for the curve to be steeper in in the ascending group. Nevertheless, discounting rates were comparable between groups, thereby supporting the view that any differences in drug effects observed between groups were due to the order of delay presentation and not to baseline differences in discounting.

Amphetamine and methylphenidate dose-dependently increased choice of the larger delayed reinforcer in the ascending group (top panels, Figure 2a). This effect is consistent with the notion that amphetamine attenuates sensitivity to reinforcer delay and it extends previous reports showing that stimulant drugs tend to increase choice of larger, delayed reinforcers (Cardinal et al. 2000; Floresco et al. 2008; Pitts and McKinney 2005; Slezak and Anderson 2011; van den Bergh et al. 2006; van Gaalen et al. 2006; Winstanley et al. 2003; Winstanley et al. 2005). However, under otherwise identical conditions, qualitatively different results were obtained in rats responding under a different order of delay presentation. In rats responding under a descending order of delay presentation, amphetamine and methylphenidate dose dependently reduced choice of the larger reinforcer and shifted the delay function downward (bottom panels, Figure 2a). Under baseline conditions, rats in the descending group began sessions responding on the lever that delivered the smaller reinforcer (in the first block that arranged the 32-s delay) and progressively shifted responding to the lever that delivered the larger reinforcer as the delay to the larger reinforcer decreased. After administration of amphetamine or methylphenidate, these rats responded relatively more on the lever that delivered the smaller reinforcer even when both reinforcers were available immediately. A drug-induced decrease in sensitivity to reinforcer delay would be expected to increase responding for the larger reinforcer early in the session (i.e., in the first blocks) when there was a longer delay to the delivery of the larger reinforcer. The effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate on response latency and on the number of trials completed were not significantly different between groups, suggesting that differences in effects on discounting were not due to differences in sensitivity to the disruptive effects of amphetamine or methylphenidate.

The parameters of reinforcement in delay discounting experiments can be varied along multiple dimensions (e.g., delay and amount), and drug effects might be mediated by changes in sensitivity to one or more of those dimensions. For example, it has been suggested that drug effects on delay discounting are due to changes in sensitivity to reinforcer delay as well as changes in sensitivity to reinforcer amount. Stimulant drugs might reduce sensitivity to reinforcer delay and/or enhance sensitivity to reinforcer amount; both effects would be expected enhance choice of larger, delayed reinforcers (for a discussion, see Pitts and Febbo 2004). Indeed, in pigeons, methamphetamine reduced sensitivity to reinforcer delay as indicated by a general flattening of the delay function (Pitts and Febbo 2004; see also Ta et al. 2008); however, it also reduced (rather than enhanced) sensitivity to reinforcer amount as indicated by a reduction in the y-intercept of the delay function (see also Maguire et al. 2009). It is unclear how changes in sensitivity to reinforcer delay and amount might interact in the current study to account for differential effects between groups. A reduction in choice of the larger reinforcer in the component with no delay in the descending group might suggest a loss of control by reinforcer amount; however, a similar reduction was not observed in the ascending group, further suggesting a significant interaction of drug effect with order of delay presentation.

One possibility is that amphetamine and methylphenidate attenuate the influence of certain variables on behavior, thereby unmasking the influence of otherwise absent or less evident variables. For example, the ability of amphetamine to promote preservative responding (e.g., Todorov et al. 1972) might override its effects on sensitivity to reinforcer delay and/or amount. Thus, responding during the later blocks of the session might be controlled more by responding earlier in the session than by the delay. This possibility is consistent with a study (St Onge et al. 2010) showing that amphetamine-induced changes in probability discounting functions (i.e., qualitatively different effects of amphetamine, depending upon the order of probabilities) are due to other effects of amphetamine (e.g., perseveration) and not to specific effects on sensitivity to reinforcer delay (or probability). A dose of amphetamine as small as 0.5 mg/kg was sufficient to promote the apparent perseverative effect in rats (St. Onge et al. 2010).

In order to assess the generality of drug interactions with delay order, two nonstimulant drugs were also assessed. Morphine dose-dependently decreased responding for the larger reinforcer in blocks with no delay or shorter delays, resulting in a flattening of the delay function in both groups and demonstrating that the effects of morphine were not dependent on the order of delay presentation. These data are consistent with previous research suggesting that morphine increases choice of smaller, immediate reinforcers (Pitts and McKinney 2005; Pattij et al. 2009). However, in both groups of rats morphine reduced responding for the larger reinforcer when both reinforcers were available immediately, suggesting that morphine impacts other processes instead of or in addition to sensitivity to reinforcer delay. One possibility is that morphine attenuates the reinforcing effectiveness of food and thus reduces sensitivity to reinforcer amount. However, in previous studies using rats responding under conditions that were similar to the conditions used in the current study, pre-session access to food failed to substantially alter delay functions despite significant increases in trial completion latency and decreases in the number of trials completed (e.g., Cardinal et al. 2000; Kolokotroni et al. 2011). In the current study, morphine significantly affected choice in both the ascending and descending groups at a dose (5.6 mg/kg) that neither increased trial completion latency nor decreased the number of trials completed, suggesting that a reduction in the effectiveness of food as a reinforcer cannot account for a reduction in choice of the larger reinforcer when both reinforcers are available immediately. Perhaps morphine differentially attenuated sensitivity to reinforcer amount through other mechanisms. A potentially useful experiment could manipulate other variables (e.g., number of food pellets) in the absence of variations of delay, to determine whether morphine attenuates sensitivity to reinforcer amount.

The effects of THC also were qualitatively similar between groups. THC tended to reduce responding for the larger reinforcer; however, rats in the descending group appeared to be more sensitivity than rats in the ascending group. In contrast to the current study, previous studies reported that THC (Wiskerke et al. 2011), but not the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55212 (Pattij et al. 2007), slightly increased choice of larger, delayed reinforcers in rats responding under an ascending delay procedure. Collectively, these studies suggest that cannabinoid receptor agonists, as compared with stimulant drugs, have relatively modest effects on delay discounting. Although THC enhanced behavior characteristic of some types of impulsivity in humans (e.g., disruption of stop-task performance), it failed to do so under a delay-discounting choice procedure (McDonald et al. 2003). It is unlikely that the effects of THC in the current study were influenced by the extended training and drug testing of these rats since control performances as well as the effects of amphetamine at the end of the study were not different from control performances and the effects of amphetamine at the beginning of the study, 9 months earlier.

In summary, these results support the view that amphetamine and methylphenidate can change delay discounting performance by mechanisms other than, possibly in addition to, attenuation of sensitivity to reinforcer delay (e.g., increase in behavioral perseveration). Upward shifts in delay functions in the ascending group and downward shifts in the descending group after drug administration might be explained as increases in preservation of the response patterns that occurred early in the session that continue to affect responding throughout the session. Together with other studies, these data highlight the fact that procedures varying delay (or any other independent variable) within the same session can provide a very efficient means to examine drug effects on behavior; however, that efficiency appears to be accompanied by other potentially important challenges. These results also underscore the importance of considering methodological issues when interpreting drug effects on complex behavior such as delay discounting.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Wouter Koek for providing assistance with statistical analyses. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid Fellowship from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science 00237309 (TT) and by United States Public Health Service Grants T32DA031115 (DRM), R25NS080684 (CH), and K05DA17918 (CPF). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainslie GW. Impulse control in pigeons. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;21:485–489. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. The effects of amphetamine, chlordiazepoxide, α-flupenthixol and behavioural manipulations on choice of signalled and unsignalled delayed reinforcement in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2000;152:362–375. doi: 10.1007/s002130000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Mitchell SH. Drug effects on delay discounting. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: the behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. pp. 213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, Ryan CN. The pharmacology of impulsive behaviour in rats: the effects of drugs on response choice with varying delays of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:161–170. doi: 10.1007/s002130050121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Tse MTL, Ghods-Sharifi S. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic regulation of effort- and delay-based decision making. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1966–1979. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AT, Hand DJ, Reilly MP. Impulsive choice in a rodent model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2008;187:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Woods JH. Effects of selective dopaminergic compounds on a delay-discounting task. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:300–311. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283473bcb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolokotroni KZ, Rodgers RJ, Harrison AA. Acute nicotine increases both impulsive choice and behavioural disinhibition in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:455–473. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW. Research on self-control: an integrating framework. Behav Brain Sci. 1988;11:665–679. [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsivity: ihe behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DR, Rodewald AM, Hughes CE, Pitts RC. Rapid acquisition of preference in concurrent schedules: effects of d-amphetamine on sensitivity to reinforcement amount. Behav Processes. 2009;81:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Niven JA, Rachlin H, editors. Quantitative analyses of behavior: Vol. 5. The effect of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement value. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; NJ: 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J, Schleifer L, Richards JB, de Wit H. Effects of THC on behavioral measures of impulsivity in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1356–1365. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T, Janssen MCW, Schepers I, González-Cuevas G, Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant on distinct measures of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;193:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0773-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattij T, Schetters D, Janssen MCW, Wiskerke J, Schoffelmeer ANM. Acute effects of morphine on distinct forms of impulsive behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:489–502. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Madden GJ. Discounting and pathological gambling. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: the behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RC, Febbo SM. Quantitative analyses of methamphetamine’s effects on self-control choices: Implications for elucidating behavioral mechanisms of drug action. Behav Processes. 2004;66:213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitts RC, McKinney AP. Effects of methylphenidate and morphine on delay-discount functions obtained within sessions. J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;83:297–314. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.47-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Green L. Commitment, choice and self-control. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972;17:15–22. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.17-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. J Exp Anal Behav. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JB, Mitchell SH, de Wit H, Seiden LS. Determination of discount functions in rats with an adjusting-amount procedure. J Exp Anal Behav. 1997;67:353–366. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1997.67-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles E, Vargas PA, Bejarano R. Within-subject differences in degree of delay discounting as a function of order of presentation of hypothetical cash rewards. Behav Processes. 2009;81:260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slezak JM, Anderson KG. Effects of variable training, signaled and unsignaled delays, and d-amphetamine on delay-discounting functions. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:424–436. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305ef9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slezak JM, Anderson KG. Effects of acute and chronic methylphenidate on delay discounting. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Onge JR, Chiu YC, Floresco SB. Differential effects of dopaminergic manipulations on risky choice. Psychopharmacology. 2010;211:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1883-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh FS, Bloemarts E, Groenink L, Olivier B, Oosting RS. Delay aversion: effects of 7-OH-DPAT, 5-HT1A/1B-receptor stimulation and D-cycloserine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TA W-M, Pitts RC, Hughes CE, McLean AP, Grace RC. Rapid acquisition of preference in concurrent chains: effects of d-amphetamine on sensitivity to reinforcement delay. J Exp Anal Behav. 2008;89:71–91. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2008.89-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov JC, Gorayeb SRP, Correa DL, Graeff FG. Effects of amphetamine on choice behavior of pigeons. Psychopharmacologia. 1972;26:395–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00421905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen MM, van Koten R, Schoffelmeer ANM, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Critical involvement of dopaminergic neurotransmission in impulsive decision making. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and discounting: Multiple minor traits and states. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: the behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. pp. 323–357. [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Dalley JW, Theobald DEH, Robbins TW. Global 5-HT depletion attenuates the ability of amphetamine to decrease impulsive choice on a delay-discounting task in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170:320–331. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Theobald DEH, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Interactions between serotonin and dopamine in the control of impulsive choice in rats: therapeutic implications for impulse control disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:669–682. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiskerke J, Stoop N, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer ANM, Pattij T. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation mediates the opposing effects of amphetamine on impulsive action and impulsive choice. PloS one. 2011;6:e25856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Mitchell SH, Bickel WK. Delay discounting and substance abuse-dependence. In: Madden GJ, Bickel WK, editors. Impulsivity: the behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2010. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]