Abstract

The Bacillus subtilis DesK/DesR two-component system regulates the expression of the des gene coding for the Δ5 acyl lipid desaturase. It is believed that a decrease in membrane lipid fluidity activates the DesK/DesR signal transduction cascade, which results in synthesis of the Δ5 acyl lipid desaturase and desaturation of membrane phospholipids. These newly synthesized unsaturated fatty acids then act as negative signals of des transcription, thus generating a regulatory metabolic loop that optimizes membrane fluidity. We previously suggested that DesK is a bifunctional enzyme with both kinase and phosphatase activities that could assume different signaling states in response to changes in the fluidity of membrane lipids. However, no direct experimental evidence supported this proposed model. In this study, we show that the C-terminal fragment of the DesK protein (DesKC) indeed acts as an autokinase. Addition of the response regulator DesR to phosphorylated DesKC resulted in rapid transfer of the phosphoryl group to DesR. Further, phosphorylated DesR can be dephosphorylated in the presence of DesKC, thus demonstrating that the sensor kinase has the ability to covalently modify DesR through both kinase and phosphatase activities. We also present evidence that DesKC might be locked in a kinase-dominant state in vivo and that its activities are not affected either in vivo or in vitro by unsaturated fatty acids. These findings provide the first direct evidence that the transmembrane segments of DesK are essential to sense changes in membrane fluidity and for regulating the ratio of kinase to phosphatase activities of the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain.

Fatty acids are the major constituents of membrane glycerolipids. Many organisms, including bacteria, regulate their lipid composition in response to growth temperature. In most organisms this involves increasing the fraction of unsaturated phospholipid acyl chains as the growth temperature decreases. This regulatory mechanism system, called thermal control of fatty acid synthesis, is thought to be designed to ameliorate the effects of temperature changes on the physical state of the membrane phospholipids. Bacillus subtilis responds to a decrease in the ambient growth temperature by introducing a double bond into the acyl chains of membrane phospholipids. This double bond is inserted by a specific membrane-bound Δ5 acyl lipid desaturase (Δ5-Des) (2, 6). A novel pathway, termed the Des pathway, designed to control the synthesis of this enzyme has recently been described (1). This pathway responds to a decrease in growth temperature by enhancing the expression of the des gene coding for Δ5-Des. The Des pathway is uniquely and stringently controlled by a two-component system composed of a membrane-associated kinase, DesK, and a soluble transcriptional activator, DesR. In previous work, evidence was presented that induction of the Des pathway, under a temperature downshift (1) or by limiting the synthesis of ante-iso-branched-chain fatty acids (5), is brought about by the ability of DesK to sense a decrease in membrane fluidity. On the basis of these studies, a model was proposed hypothesizing that DesK is a bifunctional enzyme with both kinase and phosphatase activities that could assume different signaling states in response to changes in membrane fluidity (1, 5). This could be accomplished by regulating the ratio of kinase to phosphatase activities, such that a phosphatase-dominant state is present when membrane lipids are disordered, resulting in dephosphorylation of the cognate response regulator DesR, whereas a kinase-dominant state of DesK would predominate upon an increase in the proportion of ordered membrane lipids. Upon this stimulus perception, DesK would undergo autophosphorylation and, subsequently, the phosphoryl group would be transferred to the cytoplasmic response regulator DesR. Phosphorylation of DesR results in transcriptional activation of des followed by synthesis of Δ5-Des and desaturation of the acyl chain of membrane phospholipids. These newly synthesized unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs) then act as negative signaling molecules of des transcription. Thus, it was suggested that this regulatory loop composed by the Des pathway and UFAs is designed for sensing the status of membrane fluidity and to adjust the expression of the des gene accordingly. The model of stimulus perception and transduction by the two-component system DesK/DesR was proposed on the basis of both genetic and physiological evidence (1, 5). To give biochemical support to this model and begin to understand the points for regulation of the DesK sensor protein, we characterize its activities in vitro in this report. We demonstrate here that the C-terminal domain of DesK acts as an autokinase and is able to phosphorylate its cognate response regulator DesR. In addition, the kinase domain of DesK exhibits phosphorylated DesR (DesR∼P) phosphatase activity. We also present evidence that the linkage between the transmembrane segments and the cytoplasmic domain is important for the in vivo phosphatase activity of DesK and for sensing and transducing the negative signal exerted by UFAs to the C-terminal domain of the sensor kinase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and B. subtilis strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (23). Antibiotics were added to media as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg ml−1; chloramphenicol, 5 μg ml−1; kanamycin, 5 μg ml−1; erythromycin, 1 μg ml−1; lincomycin, 25 μg ml−1; spectinomycin, 100 μg ml−1. For β-galactosidase activity measurements, B. subtilis was propagated in Spizizen salts (26) supplemented with 0.5% glucose, 0.01% (each) tryptophan and phenylalanine, and trace elements (12). This medium was designated SMM.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis | ||

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | Laboratory stock |

| AKP20 | JH642 amyE::Pdes-lacZ desK::Kmr Pkm-desR | 1 |

| DA2095 | AKP20 thrC::pDG795 | This study |

| DA20K | AKP20 thrC::(Pxyl-desK) | This study |

| DA20KV | AKP20 thrC::(Pxyl-desKV188) | This study |

| AKP21 | JH642 amyE::Pdes-lacZ desKR::Kmr | 1 |

| CM21 | AKP21 thrC::(Pxyl-desR) | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 thi-1 ΔlacU169(φ80lacZΔM15) endA1 recA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 trp6 cysT329::lac inmλpl(209) | Laboratory stock |

| BL21(λDE3) | F−ompT rB− mB− | Laboratory stock |

Kmr denotes a kanamycin resistance cassette.

Genetic techniques.

Plasmid preparations, restriction enzyme digestions, and agarose gel electrophoresis were carried out according to methods described by Sambrook et al. (23). E. coli competent cells were transformed with supercoiled plasmid DNA by using the calcium chloride procedure (23). Transformation of B. subtilis was carried out by the method of Dubnau and Davidoff-Abelson (7).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Mutagenic oligonucleotides DesKV_UP and DesKV_DW (Table 2) were used to replace histidine 188 of desK with valine by overlap extension PCR (14). Plasmid pAG47 (Table 3) was used as a template. In a first round we amplified overlapping fragments in two separate PCRs. One fragment was obtained by using oligonucleotide DesK_UPB in conjunction with DesKV_DW (Table 2), and the other was obtained by using oligonucleotide DesKV_UP together with DesK_DWS (Table 2). The products were gel purified and assembled in a PCR primed with terminal oligonucleotides only (DesK_UPB and DesK_DWS), which introduce BamHI and SalI restriction sites, respectively. The histidine-replaced desK gene was named desKV188. PCR-amplified desKV188 was digested with BamHI and SalI and cloned into vector pBluescript SK(+). This plasmid was named pADV1 (Table 3). The histidine replacement by valine was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis (DNA Sequencing Facility, University of Maine). To perform in vivo complementation experiments, we replaced histidine 188 with valine by following the same strategy explained above, but we used DesK_UPS and DesK_DWBK (Table 2) as terminal oligonucleotides. This fragment was cloned into the SalI and KpnI sites of pGES40, and the resulting plasmid was named pADV2 (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Oligonucleotide name | Sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| DesKV_UP | GATCTCgtTGATACGCTTGGGCAAA |

| DesKV_DW | CGTATCAacGAGATCGCGGGCAATT |

| DesK_UPB | gaGgAtccatATGATTAAAAATCATTTTACATTTC |

| DesK_DWS | CTTTtgtcgacTTTTGAATTATTAGGAATTGCCATG |

| DesKC_UPB | gAGgATcCAtAtgCGCAAGGAGCGCGAACGAC |

| DesK_UPS | AGTAAGtcGAcAAGCTGAAAATGAGGTAAGATC |

| DesK_DWBK | ATATggtaCcTCggaTccGTTTATTTTGAATTATTAGG |

| DesKC_UPRBS | AtaatgtcgacAggaggCTTCAGTATGAAAAGCCGCAAGG |

| DesK_DWEK | GCCggtaccTgaaTTcATTTTGAATTATTAGGAATTGC |

| DesR_Bam2299 | GgatGgaTccATGATTAGTATATTTATTGCAG |

| C_Fus789 | CCAgGATCCgTTTTTATTTAAACCA |

Lowercase letters indicate variations with respect to the wild-type B. subtilis sequence. Restrictions sites are underlined.

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pDG795 | Integrates at the thrC locus of the B. subtilis chromosome, MLSr | 11 |

| pDG1731 | Integrates at the thrC locus of the B. subtilis chromosome, Spr | 10 |

| pGES40 | Pxyl cloned into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene) | G. E. Schujman, personal communication |

| pHPKS | B. subtilis replicative vector of low copy number, MLSr | 16 |

| pQE32 | E. coli expression vector (fusions to His tag) | Qiagen |

| pETGEXCT | E. coli expression vector (fusions to GST) | 24 |

| pAG47 | Pxyl-desKR cloned into pDG795 | 1 |

| pADV1 | desKV188 cloned into pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene) | This study |

| pADV2 | desKV188 cloned into pGES40 under Pxyl | This study |

| pADV3 | Pxyl-desKV188 cloned into pDG795 | This study |

| pAD2 | desK cloned into pGES40 under Pxyl | This study |

| pAD3 | Pxyl-desK cloned into pDG795 | This study |

| pCM8 | desKC with ribosome binding site cloned into pGES40 under Pxyl | This study |

| pDAV4 | desKCV188 with ribosome binding site cloned into pGES40 under Pxyl | This study |

| pDAV5 | Pxyl-desKCV188 cloned into pDG795 | This study |

| pCM9 | Pxyl-desKC cloned into pHPKS | This study |

| pAD4 | Pxyl-desK cloned into pHPKS | This study |

| pDA327 | desKC cloned into pQE32 | This study |

| pDAV32 | desKCV188 cloned into pQE32 | This study |

| pCMdesR | desR cloned into pETGEXCT | This study |

| pAG52 | Pxyl-desR cloned into pDG795 | 1 |

| pCM7 | Pxyl-desR cloned into pDG1731 | This study |

Kmr, MLSr, and Spr denote kanamycin, macrolide, and spectinomycin resistance cassettes, respectively.

Plasmid construction.

All plasmids and vectors used in this study are listed in Table 3. The portions of desK (desKC) or desKV188 (desKCV188) encoding the cytoplasmic domains were PCR amplified from plasmids pAG47 and pADV1, respectively, with oligonucleotides DesKC_UPB and DesK_DWS (Table 2). desKC and desKCV188 were digested with BamHI and SalI and cloned into the expression vector pQE32 (Qiagen). These plasmids were named pDA327 and pDAV32, respectively. pQE32 contains the phage T5 promoter and a His6 tag coding sequence so that the overexpressed cytoplasmic domains, DesKC and DesKCV188, contain a His6 tag at the N terminus. To evaluate DesK activities in vivo, we amplified desK from plasmid pAG47 with oligonucleotides DesK_UPS and DesK_DWBK. The fragment was cloned into SalI and KpnI sites of pGES40, and the resulting plasmid was named pAD2. pAD2 and pADV2 were digested with BamHI, and the 2.4-kb fragments containing Pxyl-desK and Pxyl-desKV188 were cloned into vector pDG795. The resulting plasmids were named pAD3 and pADV3, respectively. The fragment containing Pxyl-desK was also cloned into pHPKS to give plasmid pAD4. To evaluate in vivo the activities of the cytoplasmic domains of DesK and DesKV188, we PCR amplified desKC and desKCV188 from plasmids pAG47 and pADV2 with oligonucleotide DesKC_UPRBS together with DesK_DWEK and DesKC_UPRBS together with DesK_DWBK, respectively. Both PCR fragments were digested with SalI and KpnI and cloned into vector pGES40. The resulting plasmid containing desKC was named pCM8, and the one containing desKCV188 was named pDAV4. pCM8 was digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and the ∼2-kb fragment containing Pxyl-desKC was cloned into vector pHPKS, giving plasmid pCM9. pDAV4 was digested with BamHI, and the ∼2-kb fragment containing Pxyl-desKCV188 was cloned into vector pDG795. The resulting plasmid was named pDAV5. Since DesR and DesKC have very similar molecular weights, we decided to express DesR as a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein. To this end, desR was PCR amplified with oligonucleotides C-Fus and DesR_Bam2299 (Table 2) and cloned into the BamHI site of vector pETGEXCT. Proper orientation was confirmed by the restriction pattern. The resulting plasmid was named pCMdesR.

Strain construction.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The BamHI-EcoRI fragment of plasmid pAG52, containing desR under the control of the Pxyl promoter, was cloned into vector pDG1731. The resulting plasmid was named pCM7 and was used to transform strain AKP21 to give strain CM21. Strains DA20K and DA20KV were obtained by transforming strain AKP20 with plasmids pAD3 and pADV3, respectively. In all cases, threonine autotrophy was checked to confirm integration of the plasmids at the thrC locus of the B. subtilis chromosome.

Protein overexpression and purification.

The E. coli M15/pREP4 strain was used as a host for plasmids pDA327 and pDAV32, which overexpressed DesKC and DesKCV188, respectively. The overexpression and purification of both proteins was performed as follows. Transformed M15/pREP4 was grown in LB at 37°C until the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4. To induce the expression of the recombinant proteins, 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the cultures, which were then transferred to 30°C. Growth was continued for 3 h, and cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and washed with TNP buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The pelleted cells were resuspended in TNP buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole (TNPI-20) and disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation at 37,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was incubated for 1 h with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose resin (Qiagen) equilibrated with TNPI-20 buffer. The His6-tagged proteins were eluted with 50 mM imidazole and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The glycerol percentage was raised to 20%, and the proteins were conserved at −80°C for further experiments. To purify GST-DesR, the E. coli BL21(λDE3) strain was transformed with plasmid pCMdesR. The transformed strain was grown overnight in LB and then diluted 1/10 in the same medium. The culture was grown for 1 h at 37°C, and then 0.1 mM IPTG was added. Growth was continued for 4 h, and then the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C and resuspended in cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation at 8,300 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was incubated for 1 h with 50% glutathione-agarose resin (Sigma) equilibrated with 1× PBS (0.14 M NaCl, 0.27 mM KCl, 10.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4). The resin was washed several times with 1× PBS, and then GST-DesR was eluted with 5 mM glutathione and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, and 10% glycerol. The fusion protein was conserved at −80°C for further experiments.

In vitro phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, and TLC analysis.

Unless otherwise indicated, all phosphorylation assays were carried out in R buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2). For the autokinase assay, purified DesKC, at a final concentration of 10 μM, was incubated in R buffer containing 25 μM ATP in the presence of 0.25 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP/μl at room temperature. The reaction was initiated by the addition of DesKC. The phosphotransfer assays were carried out by first allowing DesKC (10 μM) to autophosphorylate for 10 min in 150 μl of R buffer and then adding an equal volume of 10 μM purified GST-DesR in R buffer. Before adding GST-DesR, an aliquot of 15 μl corresponding to time zero was withdrawn. After the addition of GST-DesR, 30-μl aliquots were withdrawn at various time points. The aliquots were mixed with 5× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer plus 50 mM EDTA to stop the reaction and kept on ice until the last portion was taken. Then the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels. To purify phosphorylated GST-DesR (GST-DesR∼P), GST-DesR was bound to glutathione-agarose resin for 1 h at 4°C. Then the resin was washed with reaction buffer to eliminate unbound protein. DesKC was autophosphorylated for 10 min at room temperature. Resin-bound GST-DesR was incubated with DesKC∼P for 30 s, and the phosphotransfer reaction was stopped by the addition of 10 mM EDTA. To eliminate DesKC∼P and [γ-32P]ATP, resin-bound GST-DesR∼P was washed with reaction buffer supplemented with 10 mM EDTA until no radioactivity was detected in the supernatant. To remove EDTA, resin-bound GST-DesR∼P was washed five times with 100 volumes of reaction buffer without Mg2+ and then GST-DesR∼P was eluted with 5 mM glutathione in the volume required for further experiments. Purified GST-DesR∼P in R buffer was immediately used to test phosphorylated GST-DesR∼P stability or for phosphatase assays. When evaluating GST-DesR∼P stability, aliquots were taken at various time points, reactions were stopped by adding 5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and 50 mM EDTA, and mixtures were kept on ice until the last portion was taken. To test DesKC phosphatase activity, 150 μl of purified GST-DesR∼P (∼10 μM) was mixed with 150 μl of 10 μM DesKC. Just before adding DesKC, an aliquot of 18 μl of GST-DesR∼P was withdrawn (time zero), mixed with 2 μl of 10× stop solution (10% SDS, 500 mM EDTA), and diluted with 20 μl of R buffer. After the addition of DesKC, samples of 36 μl each were withdrawn at various time points (see Fig. 3 and 5) and mixed with 4 μl of 10× stop solution. Two-microliter samples from each time point were analyzed on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) polyethyleneimine-cellulose plate (J. T. Baker). The plate was developed in 0.8 M LiCl and 0.8 M acetic acid, air dried, and exposed to autoradiography films. The rest of the samples were mixed with 5× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels. The radioactivities of proteins resolved on gels and proteins and Pi resolved on TLC plates were determined qualitatively by autoradiography of dried gels and TLC plates. For quantitative analysis, bands corresponding to phosphorylated proteins in gels and spots corresponding to phosphorylated proteins and free inorganic phosphate in TLC plates were cut, and radioactivity was determined with a Wallac 1209 Rackbeta liquid scintillation counter.

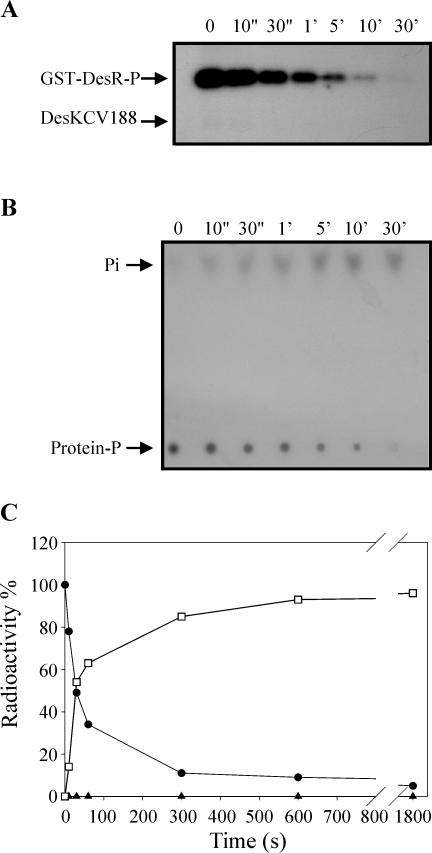

FIG. 3.

DesKC possesses GST-DesR∼P phosphatase activity. (A) GST-DesR∼P was purified as described in Materials and Methods in 150 μl of R buffer and mixed with 150 μl of equimolar DesKC in R buffer at 25°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated times, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 10× stop solution (10% SDS, 500 mM EDTA). Five percent of each time point sample was separated for TLC analysis (see below), and the rest was processed and subjected to SDS-PAGE as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (B) TLC analysis was performed to analyze the destination of the label at each time point (see Material and Methods). Five percent of the samples was applied to a polyethyleneimine-cellulose plate (J. T. Baker) which was developed in 0.8 M LiCl and 0.8 M acetic acid. The plate was air dried and exposed to autoradiography films. (C) Quantitation of phosphoproteins from the gel was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. To determine the ratio of released Pi to total phosphoproteins, spots from each time point were cut from the TLC plate and the radioactivity was determined on a liquid scintillation counter. The label on GST-DesR∼P at the initiation of the reaction (0 s) was considered 100%. Circles correspond to GST-DesR∼P, triangles correspond to DesKC∼P, and squares correspond to free Pi.

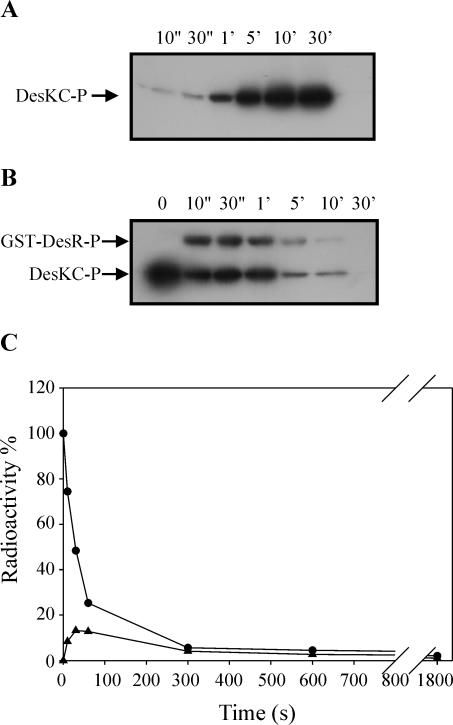

FIG. 5.

His188 is not essential for DesKC phosphatase activity. Purified GST-DesR∼P in 150 μl of R buffer was mixed with 150 μl of equimolar DesKCV188 in R buffer at 25°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated times, and reactions were stopped and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (B) TLC analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3B to analyze the destination of the label. (C) Quantitation of phosphoproteins was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. Determination of the ratio of released Pi to phosphoproteins was perform as described in the legend to Fig. 3C. The label on GST-DesR∼P at the initiation of the reaction (0 s) was considered 100%. Circles correspond to GST-DesR∼P, triangles correspond to DesKCV188 (no DesKCV188∼P was detected), and squares correspond to free Pi.

β-Galactosidase assays.

B. subtilis strains harboring Pdes-lacZ fusions were grown overnight in Spizizen minimal salts (26) supplemented with 0.5% glucose, tryptophan and phenylalanine (50 μg of each/ml), trace elements (12), and 0.05% casein hydrolysate. This medium was named SMM-CAA. The cells were collected by centrifugation and diluted in SMM-CAA containing or not containing 0.8% xylose. Samples were taken at 1-h intervals after resuspension and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (18). The specific activity was expressed in Miller units (19).

RESULTS

DesK autokinase activity.

We wished to identify the activities of the sensor protein DesK contributing to the regulation of the expression of the B. subtilis acyl lipid desaturase. It was proposed that DesK is a bifunctional enzyme with both kinase and phosphatase activities that could assume different signaling states in response to changes in membrane fluidity (1, 5).

To examine in vitro the kinase activity of DesK, suggested by the sequence similarity to other kinases, we tried to express the complete B. subtilis desK gene in E. coli with different expression systems. As several attempts to overproduce the membrane-associated form of DesK have failed, we decided to construct an N-terminal truncated form of the protein in the histidine fusion vector pQE32 (Qiagen). This 26.5-kDa protein, named DesKC, provides a simplified purification due to its soluble nature. Having its N-terminal amino acids deleted, DesKC retains the majority of the DesK cytoplasmic domain, which includes the highly conserved kinase domain. DesKC was expressed from plasmid pDA327 in the E. coli expression strain M15/pREP4 and purified as a His-tagged fusion protein (see Materials and Methods). According to the two-component signal transduction paradigm, DesKC would first undergo autophosphorylation in a conserved histidine residue, and then the phosphate would be transferred to a conserved aspartate residue in its cognate transcriptional regulator DesR. As shown in Fig. 1A, DesKC is able to undergo autophosphorylation in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. This reaction required Mg2+, since the autophosphorylation of DesKC was inhibited in the presence of EDTA (data not shown), suggesting that Mg2+-ATP is the substrate of the autokinase. According to homology studies, the conserved DesKC His188 residue would be the phosphoacceptor amino acid. In agreement with this prediction, the DesKCV188 mutant protein, where the His188 was replaced with a valine residue, was unable to undergo autophosphorylation (data not shown), indicating that the phosphorylation takes place in the conserved histidine residue.

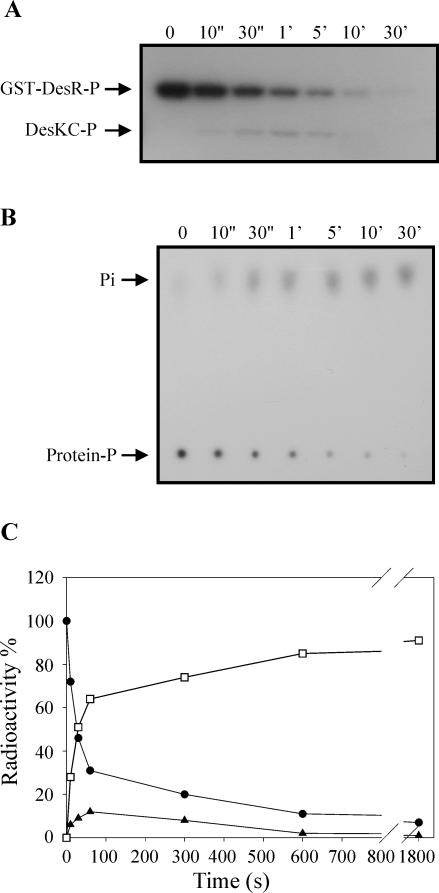

FIG. 1.

DesKC autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer from DesKC∼P to GST-DesR. (A) Purified DesKC, at a final concentration of 10 μM, was incubated in R buffer containing 25 μM ATP in the presence of 0.25 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP/μl at 25°C. The reaction was initiated by the addition of DesKC, and aliquots were removed at the indicated times. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 5× SDS gel loading buffer plus 10 mM EDTA and kept on ice until the last portion was taken. The samples were then subjected to SDS-12% PAGE analysis. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and exposed for autoradiography. (B) DesKC was first allowed to autophosphorylate for 10 min as indicated in Materials and Methods, and then an equimolar fraction of GST-DesR was added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was kept at 25°C, and aliquots were removed at the indicated times. The reactions were stopped and processed as described for panel A. (C) To quantitate the phosphoproteins, bands were cut from the gel and the incorporation of 32P was determined on a liquid scintillation counter. The label on DesKC∼P at the initiation of the reaction (0 s) was considered 100%. Circles correspond to DesKC∼P, and triangles correspond to GST-DesR∼P.

Phosphotransfer from DesKC∼P to DesR.

The next step in the two component signal transduction cascade is the activation by phosphorylation of the cognate response regulator by the corresponding kinase. To investigate this step, DesKC was subjected to autophosphorylation for 10 min and then mixed with purified GST-DesR, resulting in phosphorylation of the response regulator (Fig. 1B). The rate of the reaction was rapid, as the level of GST-DesR∼P reached a maximum within 30 s (Fig. 1C), and then the label from both proteins, DesKC∼P and GST-DesR∼P, started to decrease, reaching nondetectable levels after 30 min of incubation at 25°C. This activity was absolutely Mg2+ dependent, as no phosphorylation activity was detected in the presence of 10 mM EDTA (data not shown).

Phosphatase activity of DesKC.

It is known that response regulators have an autophosphatase activity that ensures that the proteins are not permanently activated by phosphorylation and that the magnitude of this activity varies among different response regulators (28). To test whether the dephosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P shown in Fig. 1B was due to an autophosphatase activity of the response regulator, we decided to determine the stability of GST-DesR∼P. To this end, the GST-DesR∼P formed by phosphotransfer from DesKC∼P was purified as described in Materials and Methods and then incubated at 25°C in R buffer, and the extent of phosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 2, much of the GST-DesR∼P remained after 30 min of incubation and some GST-DesR∼P could still be detected after 90 min. From these data, the half time of hydrolysis is about 51 min, which is much higher than the values obtained (40 s) for dephosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P when it is incubated with DesKC in the phosphotransferase reaction mixture (Fig. 1C). This result is consistent with previous genetic experiments that suggested that DesK would also possess a phosphatase activity. To confirm this assumption, we examined whether purified DesKC catalyzed the dephosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P. To this end, the stability of purified radiolabeled GST-DesR∼P was examined in the presence of DesKC. As shown in Fig. 3A and C, the addition of DesKC resulted in the rapid dephosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P, with the transient formation of DesKC∼P followed by complete dephosphorylation of both proteins after 30 min. Analysis of the GST-DesR∼P dephosphorylation reaction by TLC identified the product of the reaction as Pi (Fig. 3B). The addition of ADP to the dephosphorylation reaction mixture does not regenerate a significant amount of ATP, as seen for others systems (4, 25), nor does it affect the rate of GST-DesR∼P dephosphorylation (data not shown). These findings indicate that DesKC is a DesR∼P phosphatase.

FIG. 2.

Stability of GST-DesR∼P. (A) GST-DesR∼P was purified as described in Materials and Methods and kept at 25°C in R buffer. Aliquots were removed at the indicated times, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 5× SDS gel loading buffer plus 10 mM EDTA and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (B) The label on GST-DesR∼P at assayed times was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. The label on GST-DesR∼P at the initiation of the experiment (0 min) was considered 100%. The ratio of remaining GST-DesR∼P was plotted versus time.

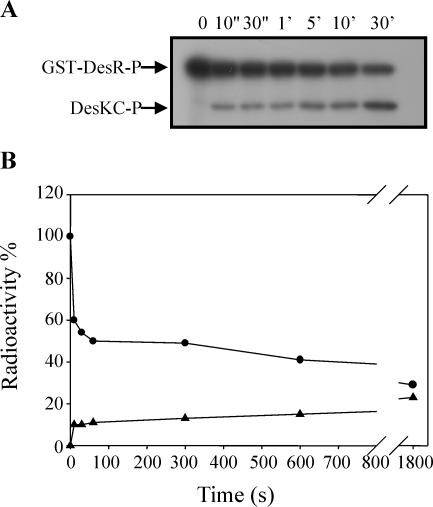

Magnesium ion requirement in the phosphatase reaction.

It has been reported that Mg2+ is a necessary cofactor for the phosphatase activity of several histidine kinases (21, 27). To test the role of the Mg2+ ion in the phosphatase activity of DesKC, we ran the assay in R buffer in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. As shown in Fig. 4, the addition of EDTA significantly decreased the dephosphorylation of GST-DesR∼P and favored the reverse phosphotransfer, increasing the ratio of DesKC∼P to GST-DesR∼P (Fig. 4). These results indicate that DesKC contains a Mg2+-dependent phosphatase activity that acts on GST-DesR∼P and that, in the absence of this cation, the reverse phosphotransfer from GST-DesR∼P to DesKC is favored.

FIG. 4.

Effect of magnesium depletion on DesKC phosphatase activity. GST-DesR∼P was purified as described in Materials and Methods and mixed with an equimolar fraction of DesKC in R buffer at 25°C in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. Aliquots were removed at the indicated times, and the reactions were stopped and processed as described in the legend to Fig. 1A. (B) Quantitation of radioactivity on phosphoproteins was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1C. The label on GST-DesR∼P at the initiation of the reaction (0 s) was considered 100%. Circles correspond to GST-DesR∼P, and triangles correspond to DesKC∼P.

Effect of V188 mutation on DesKC reverse phophotransfer and phosphatase activities.

To assess the involvement of the conserved autophosphorylation site His188 in both the phosphatase activity and the reverse phosphotransfer, we used DesKCV188 instead of DesKC in the phosphatase assay. In agreement with results obtained with other sensor kinases, there was no reverse transfer of the label under the conditions tested, indicating that the conserved His188 is the target residue that accepts the phosphate from GST-DesR∼P (Fig. 5A). However, the mutant protein DesKCV188 exhibited the same level of phosphatase activity as DesKC (Fig. 5). This points out that His188 does not play an essential role in the phosphatase activity of DesKC.

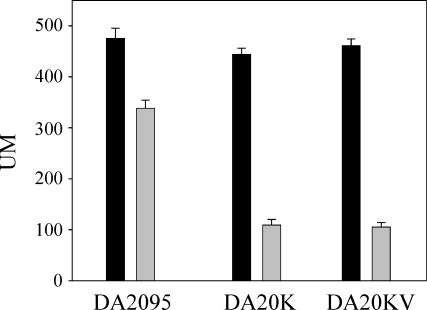

Phosphatase activity of DesKV188 in vivo.

The results presented above indicate that His188 is not required for in vitro DesKC phosphatase activity. To further analyze the role of the His188 substitution mutation in vivo, we took advantage of the observation that DesR can be phosphorylated without the assistance of DesK in the DesK-null strain AKP20 (Table 1) that overexpress DesR from the strong kanamycin promoter (Pkm) (1). A sensitive in vivo phosphatase assay has been carried out based on this phenomenon. In this strain overproducing DesR and carrying the Pdes-lacZ transcriptional fusion, β-galactosidase activity is constitutively expressed at 37°C, likely due to DesR∼P generated by a second kinase or another phosphodonor, such as acetyl phosphate (1). If DesK or DesKV188 is able to exhibit phosphatase activities in vivo, DesR∼P should be dephosphorylated in cells expressing either DesK or DesKV188, resulting in reduced activity of β-galactosidase. For this experiment, we constructed strains DA20K and DA20KV carrying the desK gene or the desKV188 open reading frame, respectively, under the control of the xylose-inducible promoter Pxyl integrated at the thrC locus. In the absence of xylose, both strains expressed high levels of β-galactosidase (Fig. 6), which were reduced about fivefold after 4 h of xylose induction (this repression was not observed in the control strain DA2095). It is worth mentioning that in a wild-type strain the Pdes-lacZ fusion is repressed in a similar way under the same culture conditions (5). This result indicates that DesKV188, as well as DesK, functions as a phosphatase in vivo.

FIG. 6.

His188 is not essential for DesKC phosphatase activity in vivo. Strains DA2095 (AKP20 thrC::pDG795), DA20K (AKP20 thrC::Pxyl-desK), and DA20KV (AKP20 thrC::Pxyl-desKV188) (Table 1) were grown overnight at 37°C in SMM supplemented with 0.01% threonine and 0.05% casein hydrolysate. Cells were collected and diluted either in the presence (grey bars) or in the absence (black bars) of 0.8% xylose. β-Galactosidase activities were determined 4 h after dilution. The results shown are the averages of the results from three independent experiments. UM, Miller units.

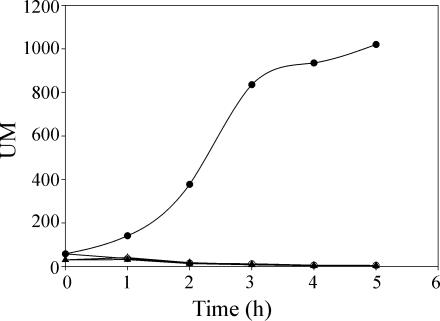

DesKC loses sensing and signaling properties in vivo.

The biochemical data shown above confirmed our previous suggestion that DesK has both kinase and phosphatase activities. To test the influence of truncated DesKC on des expression, we constructed the desK strain CM21, which expresses desR from the xylose-inducible Pxyl promoter and carries a Pdes-lacZ fusion integrated ectopically at the nonessential amyE locus (Table 1). This strain was transformed with plasmid pCM9, carrying the desKC open reading frame under the control of Pxyl. When CM21/pCM9 is grown at 37°C in the absence of the inducer, the levels of β-galactosidase are very low (Fig. 7). However, after xylose induction of DesKC, expression of β-galactosidase reached induction levels ∼25-fold higher than the levels formed in the absence of xylose (Fig. 7). This means that when the truncated DesKC protein is produced in vivo it is able to phosphorylate its cognate regulator DesR, inducing the expression of the Pdes-lacZ fusion. It should be noted that under the conditions used for the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 7 (growth at 37°C in media supplemented with casein hydrolysate), the expression of a Pdes-lacZ fusion is repressed in strain CM21 transformed with plasmid pAD4 (Table 3), which carries wild-type desK under the control of Pxyl (data not shown). The fact that induced expression of DesKC results in activation of DesR at 37°C strongly suggests that the truncated sensor protein is unable to act as a phosphatase in vivo. To further confirm this assumption, we used strain AKP20. Expression of wild-type desK in this strain results in deactivation of the constitutively phosphorylated DesR at 37°C (Fig. 6) (see also reference 1), indicating that DesK acts as a phosphatase that dephosphorylates DesR in response to an increase in growth temperature. If DesKC, as wild-type DesK, is able to exhibit phosphatase activity in vivo, DesR∼P should be dephosphorylated in cells expressing DesKC, resulting in reduced activity of β-galactosidase. When we expressed DesKC from pCM9 in AKP20 we observed that in both the absence and presence of xylose, the strain expressed high levels of β-galactosidase (data not shown). This result indicates that DesKC does not function as a phosphatase in vivo, implying that the truncated sensor protein might be locked in a kinase-dominant state.

FIG. 7.

Expression of DesKC in vivo leads to constitutive transcription of des. Strain CM21 (Pdes-lacZ desKR mutant thrC::Pxyl-desR) (triangles) and strain CM21 transformed with plasmid pCM9 (Pxyl-desKC) (circles) were grown overnight in SMM supplemented with 0.01% threonine and 0.05% casein hydrolysate at 37°C. Cells were collected and diluted in the same medium in the presence (filled symbols) or absence (empty symbols) of 0.8% xylose. Samples were taken at 1-h intervals after dilution and assayed for β-galactosidase activity. Triangles superimpose with empty circles. Each datum point is the mean of the results from three independent experiments with a mean error of less than 5%. UM, Miller units.

Genetic and biochemical evidence that transmembrane domains of DesK are essential for inhibition of des transcription by UFAs.

Previous work has shown that the transcriptional activity of the des promoter is inhibited by either endogenously synthesized or exogenously added UFAs (1, 5). To explain the control of des transcription by UFAs, two alternative models have been proposed (1). One is that UFAs inhibit des transcription by inhibiting either the kinase activity of DesK or by favoring its DesR∼P phosphatase activity. A second model is that repression is caused because in some way UFAs could mediate dissociation of DesR∼P from the des promoter. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we used strain CM21/pCM9 in which the desaturase gene is derepressed due to constitutive phosphorylation of DesR by DesKC (see above). The transcription of the des gene was not inhibited in this strain after the addition of 5 μM oleic acid, as occurs in cold-induced CM21/pAD4 cells carrying wild-type DesK (data not shown).

This result indicates that oleic acid did not affect activation of the des promoter by phosphorylated DesR nor the kinase activity of the truncated DesKC protein. Moreover, the addition of 5 μM oleic acid did not alter in vitro the autokinase, phosphotransferase, and phosphatase activities of DesKC (data not shown). All these results support the notion that the transmembrane domains of DesK are essential for sensing the presence of UFAs in membrane phospholipids. It follows that UFAs inhibit des transcription by favoring the dephosphorylation of DesR∼P in a DesK-dependent manner rather than by displacing DesR∼P from its DNA target.

DISCUSSION

Two-component signal transduction systems influence cell viability because they control fundamental responses to changes in the cell environment. In response to positive stimuli, the protein histidine kinase phosphorylates the response regulator, which then carries out some action, usually specific gene activation. Negative stimuli counteract the positive signals by a variety of mechanisms, including activating phosphatase activities specific for response regulators. Thus, a regulatory network integrates several such physiological signals to control the outcome of many two-component signaling processes. However, there is no unique model that comprehensively depicts how this regulatory network is achieved, and different strategies arise from the analysis of individual systems. Examples of catalyzed dephosphorylation of phosphoresponse regulators include those that are sensor kinase dependent, such as the B. subtilis PhoP/PhoR (25), the E. coli OmpR/EnvZ (8), and the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium PhoP/PhoQ (4). On the other hand, several response regulators also have an autophosphatase activity that ensures that the proteins are not permanently activated by phosphorylation (28). Additionally, in other systems, accessory proteins either stimulate the phosphatase reaction provided by the sensor or act independently and dephosphorylate the phosphoaspartate in the response regulator (3, 13, 20, 22).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the order-disorder transition of the lipid bilayer lamellae controls the activity of the DesK/DesR system, and it is believed that the activity of the membrane-bound sensor protein is modulated by membrane fluidity (1, 5). However, the strategy used by the DesK/DesR system to control the overall phosphorylation of the DesR transcription factor, which is finally reflected in the regulation of the transcription of the des gene, was not known. Our in vitro study demonstrates that, as previously proposed, DesK is a bifunctional enzyme having both kinase and phosphatase activities.

To analyze the putative activities of DesK, we set up the conditions for the autokinase, DesK-DesR phosphotransfer, and DesK phosphatase assays by using the C-terminal kinase domain of DesK (DesKC). We demonstrate that DesKC undergoes autophosphorylation in the presence of ATP and that the conserved His188 is the target residue of this autokinase activity. Autophosphorylated DesKC serves as a phosphodonor of the effector protein DesR, which becomes phosphorylated in the predicted Asp54 residue (L. E. Cybulski, unpublished data). Mg+2 is required for DesKC autophosphorylation and for the subsequent phosphotransfer to DesR, as shown for other two-component regulatory systems.

In the course of the phosphotransfer reaction, DesR becomes phosphorylated and it rapidly loses the label, suggesting that dephosphorylation of DesR∼P is somehow controlled by one or both partners of the DesK/DesR system. We determined that purified DesR∼P, which shows a half-life of 51 min, is rapidly dephosphorylated in the presence of DesKC and Mg2+, leading to the release of inorganic phosphate. In addition, we observed that when DesR∼P is incubated with DesKC, a transient reverse phosphotransfer takes place, which is favored in the absence of added Mg2+. The His188 residue in the sensor kinase was key to this mechanism because the mutant DesKCV188 was unable to receive the phosphate from DesR∼P. It has been suggested that an important mechanism for the signal decay of the B. subtilis response regulator PhoP∼P is the reverse reaction of transphosphorylation between PhoP∼P and its cognate sensor kinase which, in the presence of ADP, will lead to the formation of ATP (25). Although from our in vitro model we cannot assess the physiological conditions in which the reverse reaction might become relevant, it is clear that this reverse activity to dephosphorylate DesR∼P was substantially weaker than the DesR∼P phosphatase activity displayed by the sensor protein. Therefore, our in vitro data suggest that the main mechanism by which the decay of activated DesR is controlled is the DesR∼P phosphatase activity of the sensor protein rather than an autophosphatase activity of the response regulator or reverse phosphorylation.

It has been reported that the replacement of the conserved His with Val in EnvZ or PhoQ led to an inactive protein defective in autokinase and phosphatase activities (4, 8). Significantly, further mutagenesis of the His residue of EnvZ has shown that the conserved His residue is important but not required for dephosphorylation of OmpR∼P, suggesting that the conserved His is not a phosphorylated intermediate in the phosphatase reaction (15). Here we show that in vitro the mutant protein DesKCV188 was as effective as DesKC as a phosphatase, indicating that this activity structurally or functionally does not require the intactness of the conserved His188 that is the target for the autophosphorylation reaction. Moreover, using a sensitive assay to measure phosphatase activity in vivo, we demonstrated that the membrane-associated proteins DesK and DesKV188 are both able to dephosphorylate DesR∼P in vivo.

The following lines of evidence lead us to conclude that the transmembrane domains of DesK are necessary to control the cellular levels of DesR∼P: (i) expression of DesKC results in transcriptional induction of des regardless of whether the cells are grown at 37°C in an isoleucine-supplemented medium and (ii) truncated DesKC, in contrast to DesK, is unable to deactivate the constitutive des transcription generated by overexpression of DesR. These data indicate that although DesKC catalyzes in vitro the phosphorylation of DesR and the dephosphorylation of DesR∼P, this truncated protein is inactive as a DesR∼P phosphatase in vivo. Therefore, DesKC seems to be locked in the on state, being unable to sense and/or process signals in vivo. This finding presents supporting evidence for our previous proposal that the transmembrane segments play a key role in regulating the ratio of kinase to phosphatase activities of DesK.

Although most sensor kinases are anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane, only little information is available about the role of transmembrane domains. For example, the two transmembrane domains of the ArcB sensor kinase do not directly participate in signal recognition but rather serve as an anchor to keep the rest of ArcB close to the source of signal (17). Recently it was shown that the oxidized forms of ubiquinone and menaquinone electron carriers, accumulating during aerobiosis, act as direct negative signals that inhibit autophosphorylation of ArcB (9). This would explain the importance of tethering the sensor kinase to the membrane, otherwise the lipophilic quinones located exclusively in the membrane bilayer would only be able to silence a small fraction of the ArcB molecules at any given time, since most of them would be distributed through the cytosol. We show here that UFAs, which act as negative signaling molecules of des transcription, do not affect the transcriptional activation of des by DesR∼P nor the activity of truncated DesKC both in vivo and in vitro. These results extend the concept that the transmembrane segments of DesK do not merely anchor the protein to the cytoplasmic membrane but seem to be rather important, transferring a conformational change within the membrane to the cytoplasmic domain of the sensor kinase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eleonora García Véscovi for careful reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions.

This work was partially supported by a grant from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (FONCYT). D.A. is a fellow and M.C.M. is a Career Investigator of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). D.D.M. is a Career Investigator of CONICET and an International Research Scholar of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, P. S., A. M. Hernandez-Arriaga, L. E. Cybulski, A. C. Erazo, and D. de Mendoza. 2001. Molecular basis of thermosensing: a two-component signal transduction thermometer in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 20:1681-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altabe, S. G., P. Aguilar, G. M. Caballero, and D. de Mendoza. 2003. The Bacillus subtilis acyl lipid desaturase is a Δ5 desaturase. J. Bacteriol. 185:3228-3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bren, A., M. Welch, Y. Blat, and M. Eisenbach. 1996. Signal termination in bacterial chemotaxis: CheZ mediates dephosphorylation of free rather than switch-bound CheY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10090-10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castelli, M. E., V. E. Garcia, and F. C. Soncini. 2000. The phosphatase activity is the target for Mg2+ regulation of the sensor protein PhoQ in Salmonella. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22948-22954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cybulski, L. E., D. Albanesi, M. C. Mansilla, S. Altabe, P. S. Aguilar, and D. de Mendoza. 2002. Mechanism of membrane fluidity optimization: isothermal control of the Bacillus subtilis acyl-lipid desaturase. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1379-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diaz, A. R., M. C. Mansilla, A. J. Vila, and D. de Mendoza. 2002. Membrane topology of the acyl-lipid desaturase from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48099-48106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubnau, D., and R. Davidoff-Abelson. 1971. Fate of transforming DNA following uptake by competent Bacillus subtilis. 1. Formation and properties of the donor-recipient complex. J. Mol. Biol. 56:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutta, R., and M. Inouye. 1996. Reverse phosphotransfer from OmpR to EnvZ in a kinase−/phosphatase+ mutant of EnvZ (EnvZ.N347D), a bifunctional signal transducer of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1424-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Georgellis, D., O. Kwon, and E. C. Lin. 2001. Quinones as the redox signal for the arc two-component system of bacteria. Science 292:2314-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerout-Fleury, A. M., K. Shazand, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 1995. Antibiotic-resistance cassettes for Bacillus subtilis. Gene 167:335-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood, C. R., and S. M. Cuttings. 1990. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 13.Hess, J. F., K. Oosawa, N. Kaplan, and M. I. Simon. 1988. Phosphorylation of three proteins in the signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis. Cell 53:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton, R. M., H. D. Hunt, S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsing, W., and T. J. Silhavy. 1997. Function of conserved histidine-243 in phosphatase activity of EnvZ, the sensor for porin osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:3729-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson, P., and L. Hederstedt. 1999. Organization of genes for tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology 145(Pt. 3):529-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwon, O., D. Georgellis, and E. C. Lin. 2003. Rotational on-off switching of a hybrid membrane sensor kinase Tar-ArcB in Escherichia coli. J Biol. Chem. 278:13192-13195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansilla, M. C., and D. de Mendoza. 1997. l-Cysteine biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis: identification, sequencing, and functional characterization of the gene coding for phosphoadenylylsulfate sulfotransferase. J. Bacteriol. 179:976-981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Ohlsen, K. L., J. K. Grimsley, and J. A. Hoch. 1994. Deactivation of the sporulation transcription factor Spo0A by the Spo0E protein phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1756-1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkinson, J. S., and E. C. Kofoid. 1992. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 26:71-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perego, M., C. Hanstein, K. M. Welsh, T. Djavakhishvili, P. Glaser, and J. A. Hoch. 1994. Multiple protein-aspartate phosphatases provide a mechanism for the integration of diverse signals in the control of development in B. subtilis. Cell 79:1047-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Sharrocks, A. D. 1994. A T7 expression vector for producing N- and C-terminal fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Gene 138:105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi, L., W. Liu, and F. M. Hulett. 1999. Decay of activated Bacillus subtilis pho response regulator, PhoP approximately P, involves the PhoR approximately P intermediate. Biochemistry 38:10119-10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spizizen, J. 1958. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 44:1072-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stock, J. B., M. G. Surette, M. Levit, and P. Park. 1995. Two-component signal transduction systems: structure-function relationship and mechanism of catalysis, p. 25-51. In J. A. Hoch and T. J. Silhavy (ed.), Two-component signal transduction. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Zapf, J., M. Madhusudan, C. E. Grimshaw, J. A. Hoch, K. I. Varughese, and J. M. Whiteley. 1998. A source of response regulator autophosphatase activity: the critical role of a residue adjacent to the Spo0F autophosphorylation active site. Biochemistry 37:7725-7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]